The role of the behavioral health provider in supporting patients undergoing gender-affirming genital reconstructive surgery

Abstract

As gender-affirming surgery becomes more widely available, the demand for such procedures has increased accordingly. Where once genital reconstructive surgeries, such as vulvovaginoplasty, metoidioplasty, and phalloplasty, were accessible only to a select few individuals in a limited number of facilities, they are now offered to a broader cross-section of prospective patients. The life experiences, social environments, and support available to these patients vary widely, and many can benefit from the support of behavioral health professionals. While this is true for many types of reconstructive surgery, gender-affirming genital surgeries have the potential to dramatically reshape how individuals relate to their bodies across numerous domains - affecting not just gender congruence, but also sexuality and daily activities such as toileting. Behavioral health providers play a crucial role in supporting patients through the preparation and recovery processes for these surgeries. This includes helping to identify areas of a patient’s life that may complicate recovery and working with them to develop appropriate healing strategies. While the role of behavioral health providers is sometimes complicated by their parallel responsibilities in regulating access to care through the letter-writing process, they are well-positioned to support patients across the perioperative period when their expertise is used to facilitate patient readiness and recovery. This review article explores how behavioral health professionals can support the well-being of individuals undergoing gender-affirming genital surgery, from the presurgical period through long-term recovery. It is also intended to raise surgeons’ awareness of the impact of mental health and social determinants of health on the perioperative experience and to facilitate the provision of trauma-informed care and support.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

As gender-affirming surgery becomes more widely known and available, the demand for such procedures has risen accordingly. Where once genital reconstructive procedures such as vulvovaginoplasty, metoidioplasty, and phalloplasty were available to a select few individuals in only a handful of facilities, they are now available to a broader cross-section of prospective patients. However, interest in gender-affirming genital surgeries continues to outstrip demand[1]. The relative scarcity of access is duly reflected in a widespread lack of training in and awareness of these surgeries by medical professionals[1,2]. While significant improvements have been made in expanding medical education on gender-affirming care, there has been less attention focused on how mental health providers can support patients through this process - even as multiple publications emphasize the need for such support[3,4]. The current standards of care have therefore evolved to reduce the importance of referral letters in favor of a more holistic assessment and support process involving a multispecialty team[5].

Although the motivations and guidelines for their involvement have changed over the past century, mental and behavioral health providers have played a central role in assessing prospective patients since the inception of gender-affirming surgery as a discipline[3]. Behavioral health providers have historically held enormous influence over whether or not a patient is eligible for surgery, and in recent years, whether such surgery will be covered by insurance. However, this history has made many patients distrustful[3]. Patients report being fearful of personal disclosure lest the answer to an assessment question lead to a delay or denial of care, which positions providers and patients at perceived cross-purposes and potentially undermines the utility of pre-surgical letters of support[6,7]. This is problematic, as gender-affirming genital surgeries are resource-intensive and emotionally draining, and patients often experience a need for substantial support throughout the perioperative and recovery periods. For other complex surgical procedures, such as transplantation and bariatric surgery, multidisciplinary support is similarly a standard part of pre- and post-operative care[8-10]. This is sometimes referred to as surgical “prehabilitation”, referring to the fact that the goal is to identify and address issues that might affect surgical success and recovery before the surgery occurs[11].

Gender-affirming genital surgeries have the potential to dramatically reshape how someone relates to their body across multiple domains. While the literature reports high rates of satisfaction with these procedures relative to similar procedures for cisgender patients[12-14], patients frequently report that the recovery is far harder than anticipated. Behavioral health providers have an important role in assisting patients through the preparation and recovery processes, a role that is sometimes complicated by their parallel roles in regulating access to care.

THE IMPORTANCE OF A MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM

True informed consent requires that patients have the best possible understanding of a procedure[1]. While surgeons are required to provide this information as part of the formal consent process, they may not necessarily be skilled at, comfortable with, or have the extensive time to facilitate discussions of the details of how these procedures may affect the most intimate areas of a person’s life, including their effects on sexuality and relationships - with both themself and others. Behavioral health providers embedded in multidisciplinary teams can play an important role in assessing and aiding in comprehension about the likely impacts of these surgeries, ascertaining and addressing misconceptions, and facilitating communication between patients and their medical providers[3,15-17]. While there is no specific level of training required for a behavioral health provider on a surgical team, providers should ideally be highly trans competent and have a good understanding of the issues involved in accessing gender-affirming care, as well as the specific types of care offered by the team. Surgeons should also consider the specific role they would like a potential behavioral health provider to fulfill, such as pre- and post-operative supportive counseling, and hire accordingly. Embedded behavioral health providers can also play a role in educating patients’ individual therapists on how best to support their clients through this process. This function can facilitate the development of a comprehensive aftercare plan that addresses potential unexpected complications[3].

It is also important to acknowledge that, unlike other genital reconstructive surgeries - about which public awareness and opinion are generally limited - gender-affirming surgery has been thrust into broader public debate around gender-affirming care, including being prominently featured in the 2024 U.S. presidential election. This raises concerns about decreased access and increased risks related to negative perceptions of this care, how it is accessed, and its short- and long-term effects on people’s lives[18-21]. This is another factor that behavioral health providers may be called to address in their work with patients considering genital affirmation surgery, undergoing it, or recovering from it - even in the more distant past.

Finally, there continues to be a need for additional research on behavioral health needs relative to surgery and the perisurgical period. While we have provided citations where available, this paper also highlights the need for surgical fields to more systematically consider behavioral health needs as part of comprehensive, multidisciplinary care. Behavioral health support has the potential to improve patient outcomes in many domains across medicine, and embedded providers can also help prepare allied helping professionals - such as outpatient therapists and psychiatric practitioners - to support their own patients who are seeking procedures where mental health concerns may compromise recovery.

ASSESSING SURGICAL READINESS BEYOND GENDER HISTORY

Although much of the discussion of multidisciplinary assessment prior to gender affirming surgery has historically been on the individual’s gender history, the focus of assessment now is more on practical questions about the patient’s social environment and ability to recover safely and successfully [Table 1]. In part, this is because patients are unlikely to have presented to surgical assessment without significant documentation of their gender history and - particularly in the case of genital gender-affirming surgery - are likely to be far enough along in their gender affirmation process that their identity is well established.

Critical aspects of the social environment

| Area | Potential concerns |

| Housing | Stability of housing Access to a toilet and bath or shower Pets in the home (cleanliness/need for caregiving) Private place to engage in post-surgical care needs (e.g., dilation) Who else is present in the home (are they safe to be around/aware of surgery)? |

| Post-surgical support | Who will care for the patient after surgery? What is their relationship with the patient, and is it stable? Are they aware of all necessary care, willing to assist with it, and available as needed for the full recovery period? Can they come to a pre-surgical appointment to ask questions/express concerns? Is a backup caregiver available, if needed? |

| Finances | Does the patient have sufficient financial resources to sustain them through recovery (i.e., pay for housing, food, and other essential needs)? Assistance with applying for short-term disability, as appropriate Assistance with applying for leave from appointment Assessment of employment stability/ability to return to work after leave |

| Mental health | Full mental health history, including any medications Discussion of coping skills and any needed adaptations for post-surgery (e.g., a change from running to a sedentary activity) Relationship with a therapist who can be helpful in the perioperative period |

There is, however, one area of assessment that is often best addressed by a behavioral health provider embedded within the surgical center - whether the patient’s expectations are reasonable with respect to surgical outcomes. Providers should assess not only the patient’s goals for surgery - e.g., being able to stand to pee, have vaginal intercourse, or stop experiencing menstruation - but whether those goals are realistic given the surgeon and the procedure in question. Ideally, patients should be shown pictures of surgical outcomes so that they have a clear understanding of the expected aesthetic results of their surgery, informed about the risk of complications and side effects seen in the practice, and given an opportunity to discuss any doubts or concerns. They should also be asked to describe how they expect their body to function after surgery, so that any misconceptions can be addressed in advance.

After ensuring that the patient’s surgical expectations are realistic, the most salient aspect of assessment is their ability to undergo and recover from surgery - psychologically, financially, and practically. While many of these issues are addressed in more detail below, a useful framework is that the provider generally does not determine whether the patient can have surgery, but rather when they will be able to have it safely and recover with as few anticipated problems as possible. However, if the patient is unlikely to ever be appropriate or ready for surgery, this should be clearly communicated to them so that they can explore other options.

SEXUALITY AND SURGICAL DECISION MAKING

In addition to gender affirmation, the decision to undergo genital affirmation surgery involves numerous considerations about sexual interests and goals. Individual goals may affect both interest in having surgery and the type of surgery that patients are considering [Table 2]. Understanding a patient’s sexual goals and post-surgical sexual expectations is important for advising them about which, if any, procedures can help them achieve them. When engaging in shared decision-making processes, “teach-back” methods can be used to elicit patient understandings of these specifics and have been demonstrated in other fields to show higher rates of both satisfaction and compliance with aftercare needs. These can similarly be grounded through learning about how patients seek gender-affirming healthcare information (e.g., on Reddit).

Sexual goals, surgical concerns, and counseling considerations in genital gender affirming surgery

| Goal | Related concerns | Counseling recommendations | |

| Vulvoplasty/Vulvovaginoplasty | Experience penetrative vaginal intercourse | Expectations around arousal and lubrication, and how this affects graft choice | Lubricants for sexual activity and dilation are recommended for all graft options; therefore, this should not be a primary consideration in procedure choice[22]. Specifically, women should be advised that peritoneal grafts do not provide sufficient lubrication to eliminate the need for external lubricants - a common misconception amongst patients and providers alike Most cisgender women need to use external lubricants during intercourse |

| Uncertain if interested in penetration | Vulvoplasty vs. vulvovaginoplasty | Dilation needs after vulvovaginoplasty Zero- or minimal-depth surgery reduces intensity of post-surgical care, but it becomes more difficult to create a new canal at a later date - for both practical and anatomical reasons[23-25] Pros & Cons of all options for a person’s individual sexual goals | |

| Concerns about dilation regimen | Determine whether related to sexual trauma, practical concerns, anxiety, or other issues Is patient ready for surgery, or do they need time to address these issues prior to scheduling? | Build coping skills for dilation Better to do surgery when patient is prepared to dilate and can be successful Concrete plan for addressing concerns Pelvic floor physical therapy consultation | |

| Phalloplasty/Metoidioplasty | How important is sexual penetration? | Is phalloplasty or metoidioplasty more appropriate? | Penetration is not always the primary goal of individuals interested in these types of surgery, if it is a goal at all[26,27] If penetration is not a goal, are there other reasons why phalloplasty is more appropriate (e.g., “locker room” appearance, bulk, etc.) |

| Erectile function | Need for erectile device | There are a variety of techniques for achieving penile rigidity without a prosthesis (e.g., wrapping in coban tape), but most people interested in using their phallus for penetration will eventually at least consider an internal prosthesis[28] All currently available internal prosthesis options have a substantial risk of complications, including possible need for multiple replacements due to device failure or erosion of the device through the penis[29,30] | |

| “Spontaneous” erection | Does patient have achievable goals? | Discuss erectile function of the clitoris and if the goal is erection or penetration to prioritize choice of metoidioplasty vs. phalloplasty | |

| Ejaculation | Patient understanding of procedure | Address community-driven misconceptions about ejaculation after urethral lengthening. Explain that glands involved in creating semen are not present although urine or other fluids may be expelled |

It is important to start discussing patients’ sexual goals early in the consultation process. It can take time for patients to feel comfortable having these discussions with providers, and many procedural decisions are directly related to patient goals. If patients’ expectations cannot be met using current surgical techniques, it is important to know that before any surgeries take place. For example, even if a phalloplasty surgeon does not implant erectile devices, that surgeon should be confident that the patient’s goals around erectile function are possible to be met before starting construction of the phallus, or at a minimum, that the patient will be satisfied with having undergone surgery even if particular goals with respect to penetration cannot be achieved. In order to facilitate the success of these conversations, behavioral health professionals should practice having non-judgmental conversations about sexual goals that are gender and sexual orientation-inclusive. For providers who are concerned about their ability to do so without being or appearing uncomfortable, a Sexuality Attitude Reassessment (SAR) or similar type of self-awareness education may be a good option for further training[31].

EVALUATING UNCOMMON SURGICAL REQUESTS

There has been a growing conversation around genital surgery requests that fall outside the standard group of surgeries that, by and large, are designed to replicate binary expectations around genital anatomy. While historically many surgeons have been reluctant to consider performing such procedures, it is important to note that what procedures are considered standard has changed over time. For example, vulvoplasty (formerly often referred to as zero-depth vaginoplasty) used to be considered only appropriate in very specific circumstances, but it has become more widely performed.

When presented with a surgical request that falls outside routine expectations but remains technically reasonable, the behavioral health provider can play an important role in understanding the patient’s rationale for the request, whether their expectations are reasonable, and whether the surgery is likely to help them accomplish their gender goals[32]. To some extent, this functions almost as an exercise in critical reasoning - in the absence of longitudinal data, patients and providers must consider what is most important to the patient and whether, given current knowledge, there is a realistic chance of achieving it. For example, a patient who is interested in penile sparing vaginoplasty because they are focused on maintaining erectile function may not have considered either the ways that the orchiectomy would impact function or the effects on erectile function caused by the trauma to the pelvic area during dilation. Providers should also contextualize any requests within the patient’s mental health and gender history and their current psychosocial situation and help the surgeon determine whether the patient is making an informed choice that they are well prepared to undergo, recover, and live with for the long term.

ADDRESSING POTENTIAL INDICATORS OF FUTURE RECOVERY CHALLENGES

As a result of experiences of minority stress, transgender individuals are at increased risk of a number of mental health challenges that have the potential to make recovery from surgery substantially more difficult. These challenges range in severity from those primarily associated with an increased risk of patient distress to those that threaten to compromise surgical recovery. They include - but are not limited to - a history of addiction, sexual assault, and body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRB). Some sexually transmitted infections also have the potential to affect healing during the perioperative period and may be more likely to be disclosed to a behavioral health provider than in a surgical consult.

While not all of these concerns, even if present, will pose a challenge to every affected patient, providers should be attuned to these risks and prepared to have open, trauma-informed discussions about the challenges they may pose to recovery. Providers should also be prepared to create proactive treatment plans that address these concerns within the specific domain of surgical recovery, and help identify both professional and natural supports who can be called upon to provide assistance[3,33]. The following represent some, but not all, of the common mental health challenges that can present specific obstacles to recovering patients.

Self-harm and suicidality

Transgender and gender diverse individuals have been repeatedly shown to have significantly elevated rates of self-harm and suicidality. This may be the result of experiences of minority stress, trauma, depression, and other mental health difficulties. However, for some people, this can also reflect a need to take some control or ownership over their own body - which they may not otherwise feel[34]. Neither a history of self-harm nor suicidal ideation is an inherent contraindication for surgery. However, individuals should be stable enough that self-harm (e.g., cutting, burning) is not a primary coping skill and they are not experiencing active suicidal ideation. (It is important to distinguish active suicidal ideation - where people are actively thinking about how to end their life - from passive suicidal ideation - where they lack motivation to live but have no plan or intention to die. Passive suicidal ideation remains a significant concern that should be addressed, but it must also be contextualized within the individual’s social environment).

There is no specific timeline that can be followed to say that people are safe from further self-harm, suicidal ideation, or suicide attempts[35]. It is important to understand a person’s history of suicidal ideation and injury (SI) and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in order to assess its potential relevance to the perioperative time period. Behaviors that occurred a single time, or in response to a specific event, are unlikely to recur and are less of a concern than ongoing behaviors - particularly those that reflect a lower distress tolerance than may be needed to deal with the inevitable stumbling blocks that occur both before genital surgery and during recovery. Behavioral health providers should not just assess the history of these behaviors but patients’ current coping strategies for managing likely concerns.

Eating disorders

Research has repeatedly demonstrated that disordered eating is more prevalent among transgender patients relative to their cisgender peers, with the highest occurrence among transgender men, and the lowest occurrence associated with active gender-affirming hormone and surgical treatment[36,37]. The latter suggests that gender-affirming care may serve a protective function in this regard, highlighting the need for access[38]. It also emphasizes that, in addition to the multitude of well-known reasons that people of all genders may engage in disordered eating, there may be unique reasons that transgender patients may restrict their food intake related to managing their gender dysphoria[39]. Specifically, significant weight loss can affect the body in ways that impact dysphoria such as stopping menstruation or affecting the distribution of body fat[36,39].

Some literature also suggests that a history of anorexia and/or bulimia may add risk to the use of anesthesia via undetected damage to the cardiovascular system[40]. This speaks to a well-documented sequelae of acute calorie restriction caused by malnutrition and electrolyte imbalance[41]. While the common picture of disordered eating is calorie restriction, purging behaviors are equally common. These can take many forms from self-induced vomiting to the use of laxatives. Behavioral health providers should routinely assess for a range of disordered eating behaviors, both current and historical. Patients with a history of an eating disorder should be stable and in well-maintained recovery before they are appropriate candidates for surgery. However, it is important for providers to assess specific concerns and challenges patients may face during recovery to help them develop appropriate coping strategies [Table 3].

Eating disorder behaviors and related concerns

| Behavior | Concern | Assessment/Counseling need |

| Calorie restriction | Surgical recovery requires calories and proper nutrition[42] | Identify “ready to drink” supplemental nutrition that is acceptable to the patient and can be used post-surgery. May also be useful for patients with ARFID |

| Purging/Vomiting | Stress on surgical sites | Prepare the patient that nausea induced by anesthesia may be a trigger and make a plan in advance to address it |

| Oral health/dental problems that may affect anesthesia[43] | ||

| Laxative use | Concern that bowel prep may reactivate symptoms | Used shared decision making to balance the potential risks of bowel preparation for eating disorder recurrence with the benefits for surgical safety[44-47] |

| Increased risk of gastroparesis | ||

| Vaginal packing putting pressure on the colon may partially obstruct the movement of solid waste (vulvovaginoplasty only) | Prepare patient in advance to address cognitions related to previous laxative use and disordered eating behaviors | |

| Compulsive exercise | Need for activity restriction can cause depression both indirectly and directly from loss of the coping skill and the exercise-related endorphins | Will the patient be able to restrict activity for long enough to successfully recover? Work on developing new coping skills that the patient can use during the postoperative period |

Body dysmorphic disorder

While individuals with gender dysphoria accurately perceive a disconnect between the appearance of their gendered body and their internal identity, those with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) inaccurately perceive or appraise some aspect of their appearance[48,49]. In other words, people with BDD focus on perceived problems with their appearance, while those with gender dysphoria focus on the incongruence between their body and gender identity. They also may be distinct in their temporal focus - with those with BDD concerned about their current appearance and people with gender dysphoria concerned about both their current and future congruence[50] [Table 4].

Disambiguating BDD and gender dysphoria

| Body dysmorphic disorder | Gender dysphoria | |

| Differences in presentation | Focus on specific aspects of appearance contributing to a negative overall self-image. Typically, these are consistent with dominant societal beauty standards Focus on specific perceived flaws is about a belief that this causes the sufferer to be “ugly” or in severe cases, “disfigured” | Distress is caused by inconsistency with appearance and secondary sex characteristics perceived to be at odds with one’s lived gender Focus on specific features believed to contribute to having the appearance of an individual of non-congruent gender |

| Appraisal | The identified area is being misperceived by the individual as wrong/problematic when it is within expected limits | The fundamental concern is an accurate perception that their body parts and appearance are not in line with expectations for bodies of the affirmed gender |

| Similarities in presentation | Actions taken to remedy the distress caused by BDD may also be used by people who experience GD: mirror checking and reassurance seeking, camouflaging/excessive makeup use, avoidance and social isolation Both groups may seek out plastic and reconstructive surgery | People with gender dysphoria may also perseverate on specific, granular aspects of their appearance that are imperceptible or affectively neutral to others People with GD sometimes report a “moving target” of goals, whereby once one aspect changes, another becomes the focus of concern |

BDD and gender dysphoria are commonly confused by not only lay people but some providers. However, they are both distinct and have opposing treatment indications. Unlike BDD patients, who often decompensate after surgical attempts to remedy perceived flaws in their appearance, patients with gender dysphoria typically report high rates of satisfaction after gender-affirming surgery - often far above the general satisfaction rates associated with other surgeries[14,51-57]. However, although there is no evidence suggesting an elevated risk of BDD in individuals with gender dysphoria[58], the two conditions are not mutually exclusive. Patients can experience both conditions, and screening should be considered for those seeking any surgical procedure that focuses on external appearance, including the creation of a vulva or phallus.

Outside of the context of gender-affirming surgery, patients with BDD who seek out surgical care often find that their concerns are greatly heightened after surgery. The plastic surgery literature has amply documented cases where this has led to multiple attempts to correct what is believed to be a flaw in the procedure or healing process, one often not visible to others[49,59]. This last quality, where the perceived flaw is minimally visible (or completely invisible) to others, can lead to conflict between providers and patients who are upset that their surgeons cannot see what is so clearly apparent to them[59]. This may be accounted for by subtle differences in visual perception, although more research is needed[60,61]. Some research suggests that this may be mediated for patients with mild to moderate BDD through the use of screening and presurgical intervention[49].

Where BDD is suspected, teams should consider referring the patient for a formal assessment by a trained evaluator. While BDD is not an absolute contraindication to surgery, it does require teams to be particularly vigilant in ascertaining whether the patient’s gender dysphoria is separate from their BDD and whether their goals for addressing their gender dysphoria are achievable using surgery. Where surgery is not currently appropriate, patients should be provided with resources for accessing treatment and a plan for returning to care. Where surgery is determined to be appropriate for an individual with BDD, providers should be aware that genital surgery could potentially result in an exacerbation of BDD symptoms. There may be benefits to pharmaceutical treatment[62].

Most genital surgeries, regardless of the gender modality, require patients to focus a significant amount of time and energy on parts of their body that have already been a source of distress, albeit due to incongruence between natal sex and gender rather than dysmorphia. Regardless of a history of BDD, patients should be coached on how to balance the desire to monitor their healing progress and report back to their surgical team with the potential difficulties that may arise from compulsive or ritualized checking. Patients should be reminded in advance that it is not unusual for individuals who frequently check areas of concern in an attempt to reassure themselves to experience a paradoxical effect - where the checking exacerbates anxiety, thus intensifying the perception of common and generally safe complications, such as granulation tissue or mild wound dehiscence.

Body-focused repetitive disorders

BFRBs are conditions that lead patients to engage in behaviors such as hair pulling and excoriation (skin picking or scratching)[63,64]. During recovery, these behaviors can compromise the integrity of surgical sites by either tugging at necessary sutures or introducing harmful bacteria onto recent wounds. While they may provide stress relief and be engaged in consciously but compulsively, BFRBs can also include what are known as “automatic” behaviors, which are done without intention and may catch people by surprise only after the behavior has been engaged in for a substantial period of time[64,65].

While the exact cause of BFRBs is not fully understood, conditions that disrupt the texture of the skin, such as acne or psoriasis, can lead to an increased number of tactile cues[65]. Patients who engage in BFRBs report a sensation of itching, tingling, or “tension” in the affected area, which can only be ameliorated by engaging in the BFRB itself[65]. This can pose challenges for patients with exposed stitches or newly formed scars - both of which can trigger automatic picking behavior. Additionally, opioids commonly used in pain management routines are known to cause itchiness, and the dry air of hospital environments may draw moisture out of the skin, having the same effect. Proactive engagement with Habit Replacement Therapy can provide competing responses that keep the hands busy[66], and keeping the area covered with a sheet or light surgical dressing may reduce the risk of automatic picking. Pharmaceutical interventions such as N-acetyl cysteine have been shown to decrease skin picking[67,68], while naloxone has been used to manage itchiness caused by opioids[69].

Obsessive-compulsive disorder and related conditions

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a highly heterogeneous condition characterized by persistent ruminative thoughts alongside compulsive behaviors designed to mitigate the anxiety caused by these thoughts. Many presentations of OCD elicit substantial health anxiety, either regarding the health of the patient or people around them. Patients with contamination-based OCD will often wash to excess, and the inability to shower for as long as a week while inpatient may be an unexpected but highly distressing experience for patients.

Validated measures such as The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale can be helpful for getting a picture of the role OCD plays in an individual’s life by breaking down the condition into subdomains such as level of distress, frequency of ritualized behavior and ability to resist performing anxiety-reducing behaviors (e.g., compulsions)[70]. Exposure and response prevention therapy (EXRP), which builds a person’s natural ability to resist compulsive behavior through a process called fear-extinction, may be indicated prior to surgery[71].

The predisposition to ruminative thoughts can also make it more difficult to tolerate the anxiety of the unknown and exacerbate the distress associated with common complications such as hematoma or wound dehiscence. People with OCD may also attempt to seek reassurance from providers in excess of what is feasible on an outpatient basis during the immediate postoperative period. Communication between the surgical team and a patient’s therapist or psychiatrist may help the patient’s external care team provide additional support at this time, creating a temporary wrap-around model of care.

Survivors of sexual assault

There are a multiplicity of potentially overlapping reasons why genital surgeries may be especially difficult for patients who have survived sexual violence. These include multiple pre- and post-operative genital exams, including internal exams or placing/removing internal stents/catheters, as well as discussions of both sexual activity and intimate behaviors involving these areas that are necessitated by post-surgical recovery. It is particularly important to work with patients to consider how post-operative care, such as dilation, may be impacted by a history of sexual violence and prepare coping strategies in advance to increase the likelihood of a positive surgical outcome[72-74].

While not all survivors of sexual violence will have issues during the perioperative period, it is important to address such concerns proactively and in a trauma-informed way. By their nature, gender-affirming genital surgeries occur in an intimate region of the body, and for all patients, there is a period of adjustment to having providers routinely examining their genitals during the perioperative period. For survivors of trauma, this can be highly activating, and may be even more so depending on the gender of the provider or the relative power differential[2]. It also diverges from standard trauma-informed practices that allow individuals to opt out of genital exams when not acutely necessary, as the act of having chosen the surgery means that such exams are important for patient safety in different parts of the perioperative process. Behavioral health professionals can help patients work on coping skills to make such exams more tolerable[75,76].

Additionally, recovery from genital surgery involves a range of new sensations, many of which are quite painful, and some of which may feel replicative of injuries sustained during assault, or of the assault itself. Vaginal packing used in vulvovaginoplasty may be experienced as prolonged sharp pressure on the rectum and is often painful enough to make it difficult for patients to ignore. Other sensations may evoke a feeling of pelvic “fullness”, and traumatic dissociation may exacerbate this sensation by making it difficult for patients to orient to their surroundings and temporarily bringing them mentally back to traumatogenic events.

Similarly, while for most patients anesthesia is a neutral or even pleasant experience, the delirium induced by medications such as propofol and ketamine can cause disorientation, and their paralytic effects may create the sensation of being held or pinned down. Even in the absence of a history of assault, “emergence delirium” is a well-documented adverse reaction to anesthesia that can take the form of panic and hyperventilation[77].

Being prepared in advance for these potential effects and sensations may help mitigate them, and anecdotal evidence suggests it can reduce their likelihood or help patients recognize what is happening and feel assured that they are safe. Making a plan with patients ahead of time and communicating this to direct care staff can be crucial to providing proper trauma-informed care, including discussing with patients why examinations or other forms of care are taking place and asking for consent before they occur[78]. Providers and other medical staff should also inform patients of the reason why they are asking any question that may be perceived as invasive as a matter of routine[79,80] [Table 5].

Trauma-informed care overview

| Category | Action | Rationale |

| Communication | Introduce yourself, and state your role, to patient when entering room (may be needed repeatedly, particularly in inpatient setting) | Establishing trust |

| Ask permission before touching patient and wait for affirmative consent prior to starting care. If this is not possible (i.e., time-sensitive, emergency care) explain why (e.g., “I am going to insert a needle to drain this hematoma before it causes damage. This needs to happen immediately.”) | Restoring agency and locus of control | |

| Explain what a staff member is doing, and why they are doing it, before they do it | ||

| Provide options to patients, but only if answers can/will be respected. Do not provide options if patient does not have agency or choice is not available | ||

| Environment | Avoid blocking exits or doorways | Minimizing “fight or flight” responses |

| Address sensory stimulation needs (e.g., provide single occupancy accommodation, lower lighting, reduce sound volume) | ||

| Staffing | Minimize the number of staff in the room at the time, such as medical students or other personnel not essential to the procedure | |

| Respect patient gender preferences based on trauma history similar to those based on religious needs | Avoiding retraumatization |

Addiction

While vast improvements have been made in pain management, there is always the concern in medicine that the prescription of powerful analgesics may lead to iatrogenic harm through addiction. This is complicated substantially for patients with a past history of addiction, the risk of which has been shown to be elevated in transgender adults due to experiences of minority stress[81-83]. Unlike day surgeries, which may involve only one or two rescue doses of opioids, most genital surgery patients will require some type of advanced pain management for the duration of their inpatient stay, and typically for one to two weeks post-discharge. While many patients with a history of addiction may choose to minimize or forgo heavy pain medication in most aspects of their medical care, this approach is unrealistic after genital surgery. Constant severe pain can cause muscle tension and an inability to relax, which may complicate healing[84-86]. Undermanaged pain may also put people at higher risk of the development of chronic post-surgical pain, as well as addiction and associated consequences. Keeping patients comfortable allows them to take active steps in their recovery. Research shows that unmanaged pain may itself be a risk factor for future addiction, and this concern should be discussed and weighed against the concerns raised by narcotic use.

Nicotine use

Nicotine is well documented to be associated with wound healing complications, cardiopulmonary risk, as well as increased deep vein thrombosis (DVT) risk[33,87,88]. Nicotine dependence is therefore a substantial concern for prospective patients, and most surgeons require patients to stop using nicotine products of any kind approximately two months before surgery. Cotinine testing is routinely used to screen prospective patients prior to surgery[87,88].

Unfortunately, many of the most common tools for treating nicotine dependence are themselves nicotine-based, specifically nicotine replacement therapy using gum, lozenges, or patches[88]. In lieu of these tools, prescription medications such as varenicline may offer support, although bupropion is generally favored for its substantially lower side-effect profile. While cessation is counseled, ample evidence demonstrates that nicotine dependence can be a long-term struggle long after an individual has stopped using nicotine, and that nicotine relapse is most common during times of increased stress and decreased internal ability to self-soothe. Therefore, behavioral health professionals play an important role in helping patients develop alternative, non-nicotine-based coping skills in advance.

Other conditions of note

While psychosis and mania must be well-managed in order for patients to be able to properly consent to and undergo reconstructive surgeries safely, this does not guarantee that well-managed symptoms will not reemerge during the acute stress of recovery. As previously discussed, anesthesia is powerfully mind-altering, and common anesthetics are associated with hallucinations for a portion of the population. Similarly, paradoxical responses to common medications can trigger a range of surprising reactions. As medication is typically the front-line treatment for psychosis, all clinical staff should be aware of any existing as-needed (PRN) prescriptions for anti-psychotics.

The same is true for anxiolytics, which may also be indicated for syncopal reactions mediated by stress[89]. Discussing PRN medications ahead of surgery appears to anecdotally increase patient willingness to take them when indicated, especially if conversations are led by a behavioral health provider with whom the patient is already familiar. Syncopal reactions may impact a patient’s ability to participate in necessary postoperative care, such as dilation or wound care. Patients who have used avoidance strategies previously should be counseled that this mechanism for anxiety avoidance is likely not possible through the entire perioperative course. Alternative strategies should be provided, such as gradual desensitization or exposure, if possible.

PREPARING PATIENTS FOR THE HOSPITAL

While not universal, individuals seeking gender-affirming surgery may be in early adulthood and may have never undergone a surgical procedure before. It may be their first experience with anesthesia or an overnight hospital stay. Although much attention in both lay and clinical literature focuses on either approving a patient for surgery or caring for them longitudinally post-operatively, for many, the most challenging period is often the immediate week(s) following the procedure, during which they are partially immobilized and experience substantial discomfort[15].

Helping patients anticipate the environment in which they will be recovering, including challenges reported by others, can help future patients prepare to manage their experiences and communicate specific needs they may have during recovery. For example, research indicates that the sensory experience of being surrounded by the sounds of hospital machines can have a deleterious effect on patients’ mental health, blood pressure, and sleep quality, and by extension, surgical recovery[90,91]. Patients who are sensitive to sound (e.g., misophonia, autism spectrum disorders, certain anxiety disorders) may wish to consider bringing sensory tools such as noise-canceling headphones or earplugs. The same is true for patients with textural or olfactory needs. These can be used to form the basis of grounding exercises for patients who experience significant anxiety or overstimulation while inpatient, and are easy to communicate to other providers beyond the behavioral health team.

COMPLEX EMOTIONS IN THE PERIOPERATIVE PERIOD

Patients who have undergone a gender affirming surgery commonly experience contradictory emotions. They may feel simultaneously thrilled about having undergone the surgery that they have been waiting for and disconcerted as they realize both that this has not fixed everything in their lives and that they may have completed all the “steps” they were planning in their transition. Patients may struggle to navigate this dialectic and become concerned that they are not only excited and happy about having undergone surgery.

While ideally, the reality and normality of complex emotions after surgery are discussed with patients prior to the procedure, these are areas that a behavioral health provider is well-suited to address. Genital affirmation is, for many transgender and gender diverse people, the final formal step in their transition, and they may feel lost without having a plan for what is next. It can be helpful to strategize about other areas of life that patients want to work on. It is also important to discuss how a person’s gender journey, exploration, and growth can continue throughout life as they learn how to live and be in their affirmed body - both alone and in relationship to others.

Staged procedures

These complexities are further elevated for those undergoing staged procedures - whether planned or due to a complication. A behavioral health professional can help the patient understand the rationale for the staging and offer support through extended periods of liminality, during which the body has already undergone alteration but surgical goals have not yet been achieved. While not unique to such procedures, this experience may be most prolonged during masculinizing genital reconstructions that also involve urethral lengthening. These procedures may be performed in multiple stages, and even theoretically “single-stage” procedures can involve extended healing periods - for example, when an individual is managing a suprapubic catheter that will later need to be removed. It may also be helpful to show things such as catheters, wound vacs, and drains to patients during consultation, as people often struggle to conceptualize what these are or how they will affect their lives without seeing them in reality.

These liminal periods can cause people to have complicated feelings about their bodies and the experience of moving towards their anatomical goals. They can be intensely frustrating and lead to feelings of needing to leave one’s life on hold that may end up affecting decisions about later surgical stages - such as whether or not to undergo a prosthesis insertion after healing of the neophallus is theoretically “done.” Staged procedures may also involve unanticipated delays and require patient flexibility - for example, if a surgeon leaves a practice or there are changes in insurance eligibility - which may necessitate more intensive periods of support.

SUPPORTING THE WORK OF RECOVERY

Many individuals also experience difficulties when they come down from the initial rush of having achieved their surgical goals to the reality of how long it takes to recover from these surgeries and start to get back to “normal” life. Patients after phalloplasty and metoidioplasty often need to urinate through a suprapubic catheter for a period of time, which may require social planning as well as discussions about workplace adaptations. Behavioral health providers can help patients cope with this uncertainty, which may persist for an extended period, and assist with brainstorming solutions to practical problems outside the medical sector - such as how much to disclose to a supervisor regarding the reason for an accommodation.

Individuals who have undergone vulvovaginoplasty often express concern about the visual appearance of their genitals in the early months after surgery, particularly regarding asymmetry and swelling. These concerns may resolve over the first year of healing, but they may also reflect a limited awareness of the natural diversity of vulvas. (Notably, this lack of awareness is also common among cisgender women and healthcare providers[92-94].) Showing images of diverse bodies can be helpful, as can emphasizing that the tissues will continue to heal and settle over an extended period.

After vulvovaginoplasty, many individuals face challenges with dilation, due both to potential physical discomfort and the need to reorganize home and work schedules to accommodate this intimate activity. Behavioral health providers can support individuals in multiple ways - by helping develop coping strategies for physical or emotional discomfort during dilation and by providing practical guidance for advocating for necessary accommodations in the workplace[72]. As described above, this may be particularly difficult for individuals who have experienced physical or sexual abuse and who, while happy with their new genitals, may have difficulty caring for them in the ways needed after surgery. Ideally, behavioral health providers will have helped patients address these concerns and complete some necessary work prior to surgery. After surgery, they can remind patients of their coping and recovery plans. Pelvic floor physical therapy can also be very helpful in these circumstances[95].

SEXUALITY AFTER GENITAL SURGERY

A common concern in the weeks, months, and years after genital reconstructive surgery is how the patient’s body now works in the context of their sexual interactions. This can be a difficult conversation to initiate, due to both the general embarrassment many feel regarding sexual topics and the fact that individuals often forget that learning to navigate their natal anatomy - both alone and with others - is a gradual process. For individuals who were never comfortable enough in their bodies to engage in masturbation or partnered sex, this can be even more difficult, as they may lack the context to start figuring out what they want or with whom they want it[54,96-101].

For many people, masturbation is a critical tool for learning about their own bodies after surgery. They can learn what feels good to them and what does not, which in turn allows them to communicate this information to a partner. They can also learn some of the idiosyncrasies of their anatomy, which may be related to angles of penetration or types of lubricant that work better or worse for certain types of sexual behavior. It is important to normalize that these types of exploration are not unique to individuals who have undergone genital affirmation surgery, and that most people will need to experiment with what works best for them sexually every time they have a new sexual partner or try a new sexual activity.

Post-surgical care requirements may enhance some individuals’ sexuality. For example, a partner may engage in dilation with them as part of sex play. However, for others, the medicalization of their genitalia can make engaging with it sexually more difficult. They may want to set clear boundaries between care and sex. Furthermore, some romantic partners find challenges in the caretaking role that may negatively impact relationship satisfaction[102,103]. Figuring this out will be different for every person, and couples therapy or sex therapy may be indicated in some situations.

BEHAVIORAL HEALTH SUPPORT IN THE LONG TERM

Genital affirmation surgery represents a major milestone in a person’s life - one that, for many, has been not just a long-term goal but also perceived as the final step in their gender journey. While for most, achieving this goal is a uniformly positive experience, no longer having a goal to strive for can be disorienting. After spending years, or even decades, reaching the point of having surgery, it is not uncommon for individuals to experience the uncomfortable dialectic of feeling happy about their gender affirmation while also feeling uncertain or empty about what comes next. This phenomenon of impact bias in affective forecasting is not unique to this situation[104,105], and behavioral health providers often have substantial experience addressing these concerns in other milestone contexts (e.g., graduating from a degree program, getting married), even if they have not previously addressed them in the context of gender-affirming care. Behavioral health providers can help normalize these feelings and support individuals through these difficult periods.

Depending on their life stage, individuals may also require additional support related to their genital affirmation surgery throughout their lives. Those who enter new romantic or sexual relationships may sometimes struggle with questions of disclosure, including whether and when to inform a prospective partner about their gender history and journey[106,107]. Similar questions may arise in other contexts, particularly in situations where transgender individuals become legally vulnerable, such as under recent U.S. presidential administration rulings that have led to loss of access to identification documents associated with their affirmed sex[108,109]. Aging may also raise new questions and influence care choices - for example, if an individual loses interest in sex and considers stopping vaginal dilation (which could lead to loss of depth) or has an erectile device removed without replacement. While it is not the role of behavioral health providers to offer medical advice in these situations, they can provide support to individuals who need a safe space to consider their options.

CONCLUSION

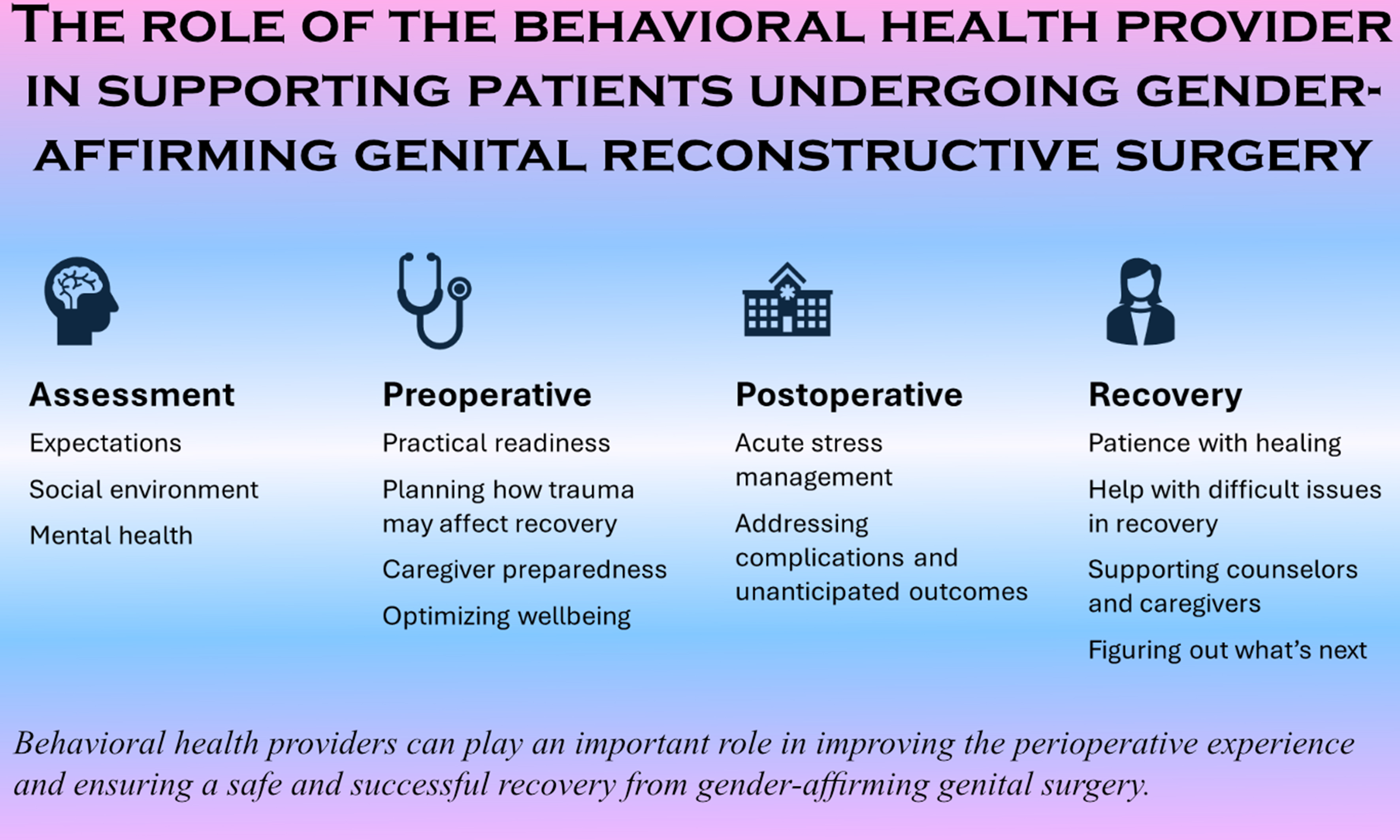

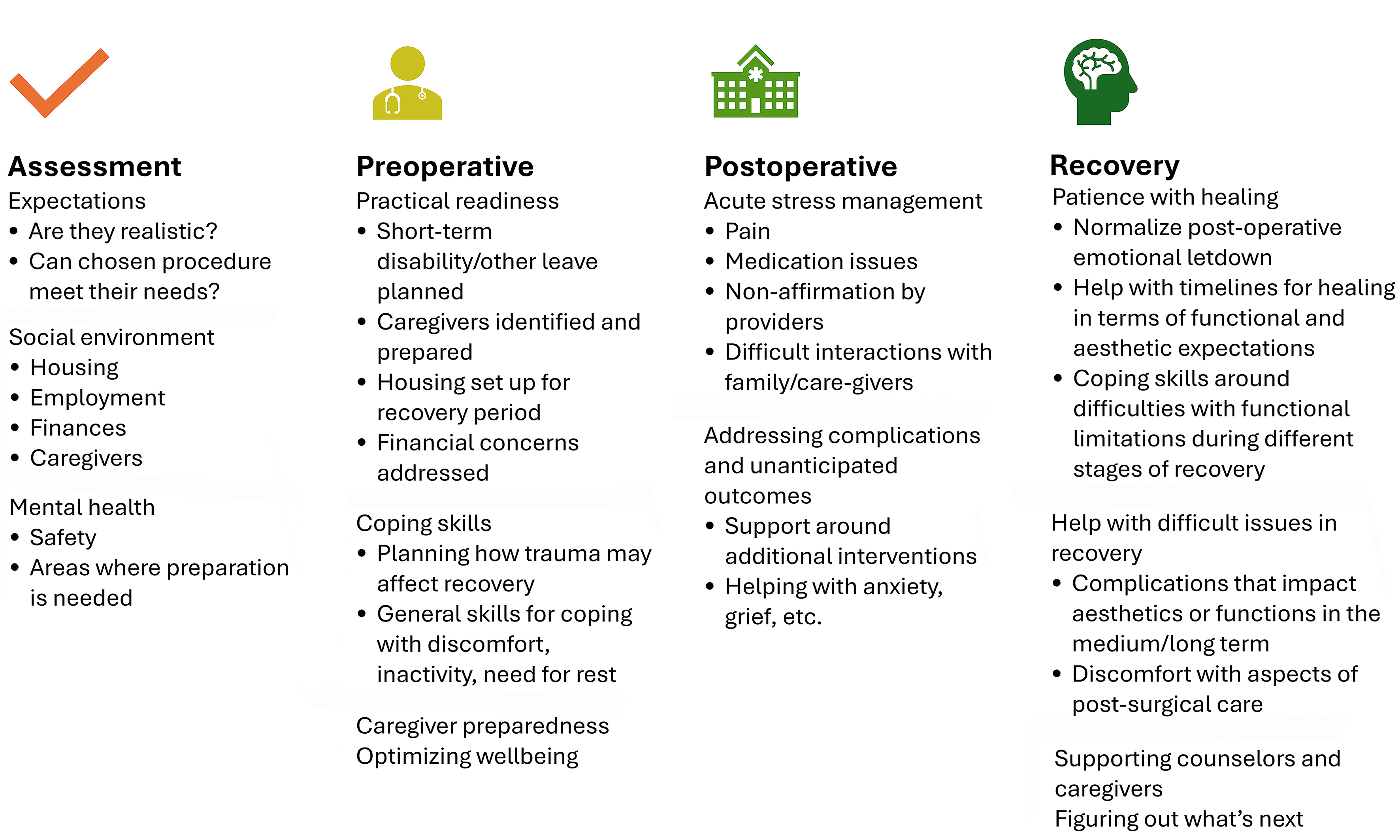

The historical reliance on psychological screening as a means of gatekeeping access to care has obscured the far more important role of behavioral health providers in improving the perioperative experience and helping ensure a safe and successful recovery from gender-affirming genital surgery [Figure 1]. While past standards of care have generally limited behavioral health providers to assessment - potentially creating an adversarial dynamic in which patients fear that their answers to basic screening questions may undermine their eligibility for surgery beyond what is medically necessary - there is growing recognition that individuals can benefit from psychosocial support throughout the perioperative period. Patients experience a wide range of emotions and support needs during the perioperative period that assessment alone does not address. Psychosocial support and counseling during the post-anesthesia, critical care, and inpatient stays can help mitigate iatrogenic distress. This is best achieved by providing comprehensive information about the range of psychosocial challenges involved in recovering from reconstructive surgery and by facilitating the necessary support. This support can be provided either through an integrated behavioral health provider on the surgical team or through appropriate referral to providers with sufficient knowledge about the surgery, thereby reducing the burden on individuals to educate their own providers. There is also a need for improved trauma-informed care training for providers working in perioperative settings to enhance the treatment experiences of not only transgender patients but also the broader population of trauma survivors.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Formulated the idea for this manuscript, wrote the initial draft, and reviewed and edited the final draft: Kant JD

Helped write the initial draft and reviewed and edited the final draft: Kuhn-Kutteh KM

Provided comments and suggestions on the initial draft and reviewed and edited the final draft: Grimstad FW

Helped write the initial draft and reviewed and edited the final draft: Boskey ER

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Boskey ER is a Junior Editorial Board Member of the journal Plastic and Aesthetic Research. Boskey ER was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Boskey ER, Kant JD. Unreasonable Expectations: A Call for Training and Educational Transparency in Gender-affirming Surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11:e4734.

2. Grimstad F, McLaren H, Gray M. The gynecologic examination of the transfeminine person after penile inversion vaginoplasty. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:266-73.

3. Roblee C, Hamidian Jahromi A, Ferragamo B, et al. Gender-affirmative surgery: a collaborative approach between the surgeon and mental health professional. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;152:953e-61.

4. Schechter LS, D’Arpa S, Cohen MN, Kocjancic E, Claes KEY, Monstrey S. Gender confirmation surgery: guiding principles. J Sex Med. 2017;14:852-6.

5. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23:S1-259.

6. Bouman W, Richards C, Addinall R, et al. Yes and yes again: are standards of care which require two referrals for genital reconstructive surgery ethical? Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2014;29:377-89.

7. Mehra G, Boskey ER, Ganor O. The quality and utility of referral letters for gender-affirming surgery. Transgend Health. 2022;7:497-504.

8. Mangarelli C, Fell G, Hobbs E, Lowry KW, Williams E, Pratt JSA. Pediatric metabolic and bariatric surgery: indications and preoperative multidisciplinary evaluation. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2024;20:1334-42.

9. De Pasquale C, Veroux M, Indelicato L, et al. Psychopathological aspects of kidney transplantation: efficacy of a multidisciplinary team. World J Transplant. 2014;4:267-75.

10. Randall J, Gordon A, Boyle C, et al. Integrating social work throughout the hematopoietic cell transplantation trajectory to improve patient and caregiver outcomes. Transplant Cell Ther. 2025;31:353.e1-12.

11. Kann MR, Estes E, Pugazenthi S, et al. The impact of surgical prehabilitation on postoperative patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Surg Res. 2025;306:165-81.

12. Bustos VP, Bustos SS, Mascaro A, et al. Regret after gender-affirmation surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9:e3477.

13. Jedrzejewski BY, Marsiglio MC, Guerriero J, Penkin A, Connelly KJ, Berli JU; OHSU Transgender Health Program “Regret and Request for Reversal” Workgroup. Regret after gender-affirming surgery: a multidisciplinary approach to a multifaceted patient experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;152:206-14.

14. Wiepjes CM, Nota NM, de Blok CJM, et al. The amsterdam cohort of gender dysphoria study (1972-2015): trends in prevalence, treatment, and regrets. J Sex Med. 2018;15:582-90.

15. Deutsch MB. Gender-affirming surgeries in the era of insurance coverage: developing a framework for psychosocial support and care navigation in the perioperative period. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27:386-91.

16. Latack KR, Adidharma W, Moog D, Satterwhite T, Hadj-Moussa M, Morrison SD. Are we preparing patients for gender-affirming surgery? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146:519e-21.

17. Selvaggi G, Giordano S. The role of mental health professionals in gender reassignment surgeries: unjust discrimination or responsible care? Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:1177-83.

18. Abreu RL, Sostre JP, Gonzalez KA, Lockett GM, Matsuno E, Mosley DV. Impact of gender-affirming care bans on transgender and gender diverse youth: parental figures’ perspective. J Fam Psychol. 2022;36:643-52.

19. Atwood S, Morgenroth T, Olson KR. Gender essentialism and benevolent sexism in anti‐trans rhetoric. Social Issues Policy Review. 2024;18:171-93.

20. Lee WY, Hobbs JN, Hobaica S, DeChants JP, Price MN, Nath R. State-level anti-transgender laws increase past-year suicide attempts among transgender and non-binary young people in the USA. Nat Hum Behav. 2024;8:2096-106.

21. Pharr JR, Chien LC, Gakh M, Flatt J, Kittle K, Terry E. Serial mediation analysis of the association of familiarity with transgender sports bans and suicidality among sexual and gender minority adults in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:10641.

22. O’Dwyer C, Kumar S, Wassersug R, et al. Vaginal self-lubrication following peritoneal, penile inversion, and colonic gender-affirming vaginoplasty: a physiologic, anatomic, and histologic review. Sex Med Rev. 2023;11:212-23.

23. Yuan N, Chung T, Ray EC, Sioni C, Jimenez-Eichelberger A, Garcia MM. Requirement of mental health referral letters for staged and revision genital gender-affirming surgeries: an unsanctioned barrier to care. Andrology. 2021;9:1765-72.

24. Ngaage LM, Knighton BJ, Benzel CA, et al. A review of insurance coverage of gender-affirming genital surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:803-12.

26. Frey JD, Poudrier G, Chiodo MV, Hazen A. A systematic review of metoidioplasty and radial forearm flap phalloplasty in female-to-male transgender genital reconstruction: is the “ideal” neophallus an achievable goal? Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4:e1131.

27. Ganor O, Taghinia AH, Diamond DA, Boskey ER. Piloting a genital affirmation surgical priorities scale for trans masculine patients. Transgend Health. 2019;4:270-6.

28. Boskey ER, Mehra G, Jolly D, Ganor O. Concerns about internal erectile prostheses among transgender men who have undergone phalloplasty. J Sex Med. 2022;19:1055-9.

29. Fraiman E, Nandwana D, Loria M, et al. Complication and explantation rates of penile prostheses in transmasculine patients: a meta-analysis. Urology. 2024;194:260-8.

30. Griggs R, Henry G, Vasylieva V, Karpman E. Mechanical failure of inflatable penile prostheses: time to failure and reasons for replacement. J Sex Med. 2025;22:909-15.

31. Kristina A, Lindroth M. Exploring the role of sexual attitude reassessment and restructuring (SAR) in current sexology education: for whom, how and why? Sex Education. 2022;22:723-40.

32. Marsiglio M, Fascelli M, Peters BR, et al. Genital gender-affirming surgery requests outside the binary: unique multidisciplinary considerations for transgender and gender diverse patients. Transgender Health. 2024;Epub ahead of print.

33. Shin SJ, Kumar A, Safer JD. Gender-affirming surgery: perioperative medical care. Endocr Pract. 2022;28:420-4.

35. Ropaj E, Haddock G, Pratt D. Developing a consensus of recovery from suicidal ideations and behaviours: a Delphi study with experts by experience. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0291377.

36. McGregor K, McKenna JL, Barrera EP, Williams CR, Hartman-Munick SM, Guss CE. Disordered eating and considerations for the transgender community: a review of the literature and clinical guidance for assessment and treatment. J Eat Disord. 2023;11:75.

37. Rasmussen SM, Dalgaard MK, Roloff M, et al. Eating disorder symptomatology among transgender individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eat Disord. 2023;11:84.

38. Swan J, Phillips TM, Sanders T, Mullens AB, Debattista J, Brömdal A. Mental health and quality of life outcomes of gender-affirming surgery: a systematic literature review. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2023;27:2-45.

39. Ålgars M, Alanko K, Santtila P, Sandnabba NK. Disordered eating and gender identity disorder: a qualitative study. Eat Disord. 2012;20:300-11.

40. Seller CA, Ravalia A. Anaesthetic implications of anorexia nervosa. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:437-43.

41. Sachs KV, Harnke B, Mehler PS, Krantz MJ. Cardiovascular complications of anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49:238-48.

42. Taormina JM, Cordoba Kissee M, Brownstone LM, et al. Approach to the patient: navigating body mass index requirements for gender-affirming surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109:2389-99.

43. Maine M, Goldberg MH. The role of third molar surgery in the exacerbation of eating disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1297-300.

44. Dragomir MA, Constantinescu A, Andronic O. Mechanical preparation of the colon before colorectal surgery - is it still actual? Maedica. 2024;19:769-74.

45. Antoniou SA, Huo B, Tzanis AA, et al. EAES, SAGES, and ESCP rapid guideline: bowel preparation for minimally invasive colorectal resection. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:9001-12.

46. Catarci M, Guadagni S, Masedu F, et al. Oral antibiotics alone versus oral antibiotics combined with mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: a propensity score-matching re-analysis of the iCral 2 and 3 prospective cohorts. Antibiotics. 2024;13:235.

47. Zhang J, Xu L, Shi G. Is mechanical bowel preparation necessary for gynecologic surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2016;81:155-61.

48. Fang A, Matheny NL, Wilhelm S. Body dysmorphic disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37:287-300.

49. Higgins S, Wysong A. Cosmetic surgery and body dysmorphic disorder - an update. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:43-8.

50. Jassi A, McLaren R, Krebs G. Body dysmorphic disorder and gender dysphoria: differential diagnosis in adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2025;34:1225-7.

51. Bustos VP, Bustos SS, Mascaro A, et al. Transgender and gender-nonbinary patient satisfaction after transmasculine chest surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9:e3479.

52. Mehringer JE, Harrison JB, Quain KM, Shea JA, Hawkins LA, Dowshen NL. Experience of chest dysphoria and masculinizing chest surgery in transmasculine youth. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e2020013300.

53. Morrison SD, Vyas KS, Motakef S, et al. Facial feminization: systematic review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:1759-70.

54. Papadopulos NA, Ehrenberger B, Zavlin D, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction in transgender men after phalloplasty in a retrospective study. Ann Plast Surg. 2021;87:91-7.

55. Park RH, Liu YT, Samuel A, et al. Long-term outcomes after gender-affirming surgery: 40-year follow-up study. Ann Plast Surg. 2022;89:431-6.

56. Schoffer AK, Bittner AK, Hess J, Kimmig R, Hoffmann O. Complications and satisfaction in transwomen receiving breast augmentation: short- and long-term outcomes. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;305:1517-24.

57. Tirrell AR, Abu El Hawa AA, Bekeny JC, Chang BL, Del Corral G. Facial feminization surgery: a systematic review of perioperative surgical planning and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10:e4210.

58. Lewis JE, Patterson AR, Effirim MA, et al. Examining gender-specific mental health risks after gender-affirming surgery: a national database study. J Sex Med. 2025;22:645-51.

59. Sweis IE, Spitz J, Barry DR Jr, Cohen M. A review of body dysmorphic disorder in aesthetic surgery patients and the legal implications. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:949-54.

60. Feusner JD, Moody T, Hembacher E, et al. Abnormalities of visual processing and frontostriatal systems in body dysmorphic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:197-205.

61. Feusner JD, Hembacher E, Moller H, Moody TD. Abnormalities of object visual processing in body dysmorphic disorder. Psychol Med. 2011;41:2385-97.

63. Houghton DC, Alexander JR, Bauer CC, Woods DW. Abnormal perceptual sensitivity in body-focused repetitive behaviors. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;82:45-52.

64. Sampaio DG, Grant JE. Body-focused repetitive behaviors and the dermatology patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:723-7.

65. Deckersbach T, Wilhelm S, Keuthen NJ, Baer L, Jenike MA. Cognitive-behavior therapy for self-injurious skin picking. A case series. Behav Modif. 2002;26:361-77.

67. Grant JE, Chamberlain SR, Redden SA, Leppink EW, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of excoriation disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:490-6.

68. Lee DK, Lipner SR. The potential of N-acetylcysteine for treatment of trichotillomania, excoriation disorder, onychophagia, and onychotillomania: an updated literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:6370.

69. He F, Jiang Y, Li L. The effect of naloxone treatment on opioid-induced side effects: a meta-analysis of randomized and controlled trails. Medicine. 2016;95:e4729.

70. Pinciotti CM, Avery J, Zhang C, et al; Latin American Trans-ancestry INitiative for OCD genomics (LATINO), Brazilian Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Work Group (GTTOC). Benchmarking empirical severity for the yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale-second edition. J Affect Disord. 2025;390:119719.

71. Song Y, Li D, Zhang S, et al. The effect of exposure and response prevention therapy on obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114861.

72. Shamamian PE, Chen D, Wang A, et al. Predictors of dilation difficulty in gender-affirming vaginoplasty. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2025;101:178-86.

73. Schardein JN, Nikolavsky D. Sexual functioning of transgender females post-vaginoplasty: evaluation, outcomes and treatment strategies for sexual dysfunction. Sex Med Rev. 2022;10:77-90.

74. Butler C, Dugi D, Dy GW. Gender-affirming surgery, care, and common complications. In: Textbook of Female Urology and Urogynecology. 5th ed. CRC Press; 2023. pp. 1270-80.

75. O’Laughlin DJ, Strelow B, Fellows N, et al. Addressing anxiety and fear during the female pelvic examination. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:2150132721992195.

76. Narr RK, Kvach E, O’Connell R. Sexual abuse and trauma-informed care for transgender and gender diverse people in Ob/Gyn practice. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/context-principles-and-practice-of-transgynecology/sexual-abuse-and-traumainformed-care-for-transgender-and-gender-diverse-people-in-obgyn-practice/7199608D7F16ED670AFDB87D381C846B. [Last accessed on 20 Jan 2026].

77. Umholtz M, Cilnyk J, Wang CK, Porhomayon J, Pourafkari L, Nader ND. Postanesthesia emergence in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Clin Anesth. 2016;34:3-10.

78. McBain SA, Cordova MJ. Clinical education: addressing prior trauma and its impacts in medical settings. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2024;31:501-12.

79. Bliton JN, Zakrison TL, Vong G, et al. Ethical care of the traumatized: conceptual introduction to trauma-informed care for surgeons and surgical residents. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;234:1238-47.

80. Fletcher KE, Steinbach S, Lewis F, Hendricks M, Kwan B. Hospitalized medical patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): review of the literature and a roadmap for improved care. J Hosp Med. 2021;16:38-43.

81. Bryan AE, Kim HJ, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI. Factors associated with high-risk alcohol consumption among LGB older adults: the roles of gender, social support, perceived stress, discrimination, and stigma. Gerontologist. 2017;57:S95-104.

82. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet M, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. Available from: https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS%20Full%20Report%20-%20FINAL%201.6.17.pdf. [Last accessed on 20 Jan 2026].

83. Kidd JD, Jackman KB, Wolff M, Veldhuis CB, Hughes TL. Risk and protective factors for substance use among sexual and gender minority youth: a scoping review. Curr Addict Rep. 2018;5:158-73.

84. Matsuzaki K, Upton D. Wound treatment and pain management: a stressful time. Int Wound J. 2013;10:638-44.

86. Baratta JL, Schwenk ES, Viscusi ER. Clinical consequences of inadequate pain relief: barriers to optimal pain management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:15S-21.

87. Sterling J, Policastro C, Elyaguov J, Simhan J, Nikolavsky D. How and why tobacco use affects reconstructive surgical practice: a contemporary narrative review. Transl Androl Urol. 2023;12:112-27.

88. Xu Z, Norwich-Cavanaugh A, Hsia HC. Can nicotine replacement therapy decrease complications in plastic surgery? Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83:S55-8.

89. Malave B, Vrooman B. Vasovagal reactions during interventional pain management procedures-a review of pathophysiology, incidence, risk factors, prevention, and management. Med Sci. 2022;10:39.

90. Brown B, Rutherford P, Crawford P. The role of noise in clinical environments with particular reference to mental health care: a narrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1514-24.

91. Hsu SM, Ko WJ, Liao WC, et al. Associations of exposure to noise with physiological and psychological outcomes among post-cardiac surgery patients in ICUs. Clinics. 2010;65:985-9.

92. Kirkman M, Dobson A, McDonald K, Webster A, Wijaya P, Fisher J. Health professionals’ and beauty therapists’ perspectives on female genital cosmetic surgery: an interview study. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23:601.

93. Moran C, Lee C. ‘Everyone wants a vagina that looks less like a vagina’: Australian women’s views on dissatisfaction with genital appearance. J Health Psychol. 2018;23:229-39.

94. Mowat H, Dobson AS, Mcdonald K, Fisher J, Kirkman M. “For myself and others like me”: women’s contributions to vulva-positive social media. Feminist Media Stud. 2020;20:35-52.

95. Kvach E, O’connell R, Sairafi S, Holland K, Wittmer N. Dilation outcomes for transgender and nonbinary patients following gender-affirming vaginoplasty in a US county safety-net system. J Womens & Pelvic Health Phys Ther. 2024;48:154-64.

96. Blasdel G, Kloer C, Parker A, Castle E, Bluebond-Langner R, Zhao LC. Coming soon: ability to orgasm after gender affirming vaginoplasty. J Sex Med. 2022;19:781-8.

97. Holmberg M, Arver S, Dhejne C. Improving sexual function and pleasure in transgender persons. In: Hall G, Binik YM, Editors. Principles and practice of sex therapy. 6th ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2020. pp. 423-54. Available from: https://www.guilford.com/books/Principles-and-Practice-of-Sex-Therapy/Hall-Binik/9781462543397/contents. [Last accessed on 20 Jan 2026].

98. Kerckhof ME, Kreukels BPC, Nieder TO, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions in transgender persons: results from the ENIGI follow-up study. J Sex Med. 2019;16:2018-29.

99. Kloer C, Parker A, Blasdel G, Kaplan S, Zhao L, Bluebond-Langner R. Sexual health after vaginoplasty: a systematic review. Andrology. 2021;9:1744-64.

100. Wierckx K, Van Caenegem E, Elaut E, et al. Quality of life and sexual health after sex reassignment surgery in transsexual men. J Sex Med. 2011;8:3379-88.

101. Wierckx K, Van Caenegem E, Weyers S, et al. Quality of life and sexual health after sex reassignment surgery in female-to-male transsexuals. J Sex Med. 2011;8:190.

102. Min J, Yorgason JB, Fast J, Chudyk A. The impact of spouse’s illness on depressive symptoms: the roles of spousal caregiving and marital satisfaction. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75:1548-57.

103. Randall G, Molloy GJ, Steptoe A. The impact of an acute cardiac event on the partners of patients: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2009;3:1-84.

104. Lench HC, Levine LJ, Perez K, et al. When and why people misestimate future feelings: Identifying strengths and weaknesses in affective forecasting. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2019;116:724-42.

105. Wilson TD, Gilbert DT. Affective forecasting: knowing what to want. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14:131-4.

106. Kade T. “Hey, by the way, I’m transgender”: Transgender disclosures as coming out stories in social contexts among trans men. Socius. 2021;7:23780231211039389.

107. Table B, Carroll RW, Holland MR. Communicating transgender identity. In: Luurs GD, editor. Handbook of research on communication strategies for taboo topics. IGI Global; 2022. pp. 126-52.

108. Coelho DRA, Chen AL, Keuroghlian AS. Advancing transgender health amid rising policy threats. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:1041-4.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].