Sexual health outcomes of non-facial gender-affirming surgery: a narrative review

Abstract

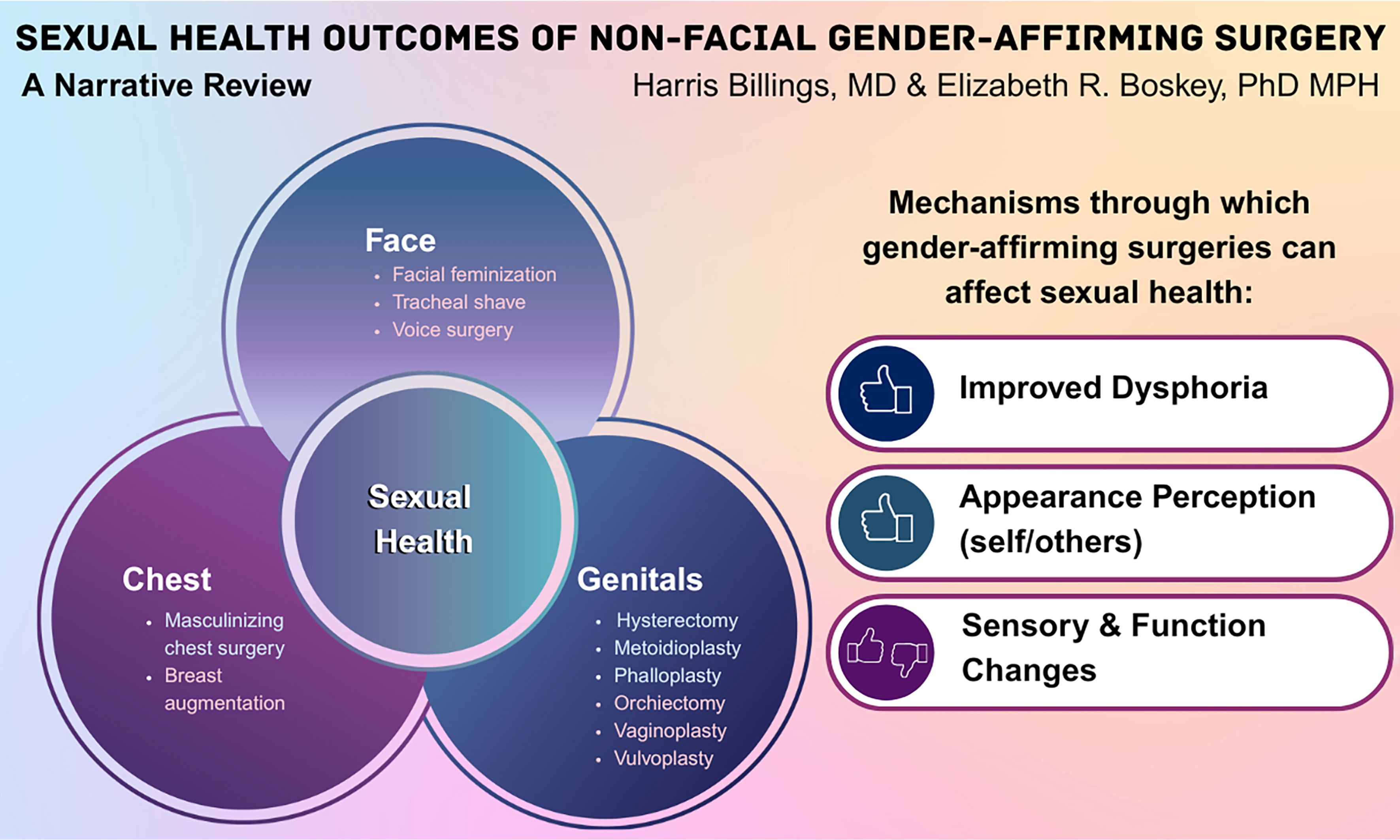

For many individuals, sexual health is an important part of overall health and well-being, yet it remains an overlooked aspect of care for transgender and gender diverse (TGD) patients. While cisgender and TGD individuals share many sexual health needs, TGD patients face unique clinical considerations that physicians - particularly surgeons - must understand in the context of gender-affirming surgery (GAS). As demand for GAS grows, it is essential that plastic surgeons and other surgical specialists recognize how these procedures affect sexual health, sexual function, and satisfaction. This review summarizes current evidence on sexual health outcomes in TGD populations following commonly performed GASs, including chest masculinization, breast augmentation, phalloplasty, metoidioplasty, vaginoplasty, and vulvoplasty. These procedures can substantially enhance quality of life (QOL) by improving body congruence and sexual well-being; however, they may also introduce anatomical, neurological, or psychosocial challenges that influence sexual health. To ensure that patients can provide fully informed consent, surgeons must understand these outcomes and communicate them effectively as part of surgical planning and throughout both pre- and postoperative care.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Sexual health is a vital component of overall health and well-being, encompassing physical and psychosocial health, freedom from violence and coercion, and access to competent healthcare[1]. Although transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals share many of the same sexual health needs as the general population, they also face unique clinical considerations - particularly in the context of gender-affirming care (GAC)[2-4].

Broadly, GAC includes hormone therapy, mental health care, social and legal support, primary care, voice therapy, sexual health counseling, and surgical interventions[4]. Although all aspects of GAC contribute to overall well-being, gender-affirming surgeries (GASs) play a particularly significant role for many TGD individuals. For those who pursue them, GAS can help achieve embodiment goals, alleviate gender dysphoria, improve psychosocial and mental health outcomes, and enhance QOL[3-7].

Accurately estimating the size of the global transgender population remains difficult due to gaps in data collection and variations in sociolegal contexts. Nevertheless, available evidence suggests that prevalence ranges from a fraction of a percent to several percentage points[4]. In the United States, recent epidemiological data suggest that the transgender population is increasing, especially among younger age groups - a trend attributed to greater social acceptance and improved survey methods[8]. Current estimates suggest that more than one million transgender individuals live in the U.S.

Data from the 2022 United States Transgender Survey (USTS) show that 56% of transgender individuals had received hormone therapy (although 88% expressed a desire for it), and 29% had at least one GAS (with 84% expressing interest in at least one surgery; see Table 1 for a breakdown by procedure)[9]. Similarly, findings from the 2019 Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) Survey in the European Union indicated that 48% of transgender respondents in the Netherlands, 46% in Germany, 36% in Sweden, and 33% in Denmark had undergone GAS, compared with an EU average of 27% (see FRA 2023 for full data)[10]. Although surgical data from low- and middle-income countries remain limited, available evidence highlights a consistent and growing global demand for gender-affirming surgical care[11].

Overview of common gender-affirming surgical procedures

| Name | Description | % Had | % Wanted | % Unsure | |

| Feminizing procedures | Breast augmentation/ “top surgery” | Similar to breast augmentation in cisgender women but with unique anatomical considerations[59,60]. Usually not pursued/recommended until breast development from hormone therapy has stabilized | 8 | 36 | 36 |

| Vaginoplasty/ “bottom surgery” | Involves penectomy, urethral shortening, orchiectomy, creation of a clitoris using the neurovascular bundle of the glans, formation of the vaginal vestibule and urethral opening, and construction of the labia. The vaginal canal is most often lined with penile-scrotal skin; other techniques use peritoneal or colon flaps. Requires lifelong dilation and douching, which may be difficult for some patients | 9* | 42 | 27 | |

| Vulvoplasty/ “bottom surgery” | Similar to vaginoplasty but without creation of a vaginal canal; also termed “zero-depth vaginoplasty”. The absence of dilation/douching requirements makes this option preferable for some women. It may also be chosen for other personal reasons | ||||

| Orchiectomy | Removal of the testes; may be performed alone for hormonal control or as part of vaginoplasty, depending on patient goals | 11 | 42 | 25 | |

| Facial feminization surgery/“FFS”** | A set of procedures designed to alter the facial and cranial appearance to a more feminine presentation. May include jaw contouring/reduction, brow and eyelid lifting, forehead and hairline contouring, rhinoplasty, and other procedures. Shown to significantly improve observer accuracy in gender perception[61] | 5 | 41 | 33 | |

| Tracheal shave | Removal of a portion of the thyroid cartilage (the “Adam’s apple”) that develops during testosterone-dependent puberty. Also known as thyroid chondrolaryngoplasty. May be performed alongside vocal cord surgery to raise the vocal pitch | 3 | 28 | 36 | |

| Masculinizing procedures | Masculinizing chest surgery/ “top surgery” | Removal of most glandular breast tissue with modification of the nipple-areola complex, and sometimes chest contouring, to create a more masculine appearance. Some non-binary individuals may prefer breast reduction rather than a full mastectomy. Patients may choose to forgo nipple grafts. Some may later have nipples tattooed | 20 | 57 | 15 |

| Hysterectomy | Typically includes bilateral salpingectomy to reduce cancer risk, may be performed with or without oophorectomy, depending on patient preference. Prerequisite for any genital surgery involving vaginectomy | 6 | 51 | 28 | |

| Metoidioplasty and phalloplasty/ “bottom surgery” | Can be performed with or without urethral lengthening, depending on the desire for standing urination. Urethral lengthening usually requires concurrent vaginectomy. Metoidioplasty uses the hormonally enlarged clitoris as the neophallus (similar to a micropenis). Phalloplasty uses a local or distant flap (various techniques) placed over the anteriorly repositioned clitoris clitoris to create a larger neophallus, potentially more suitable for penetration. Erectile implants are required for penetrative function and often require replacement; however, some patients pursue alternative methods for achieving sufficient rigidity[62] | 1/1† | 13/11 | 42/31 | |

Common GASs include masculinizing chest surgery, feminizing breast augmentation, phalloplasty, metoidioplasty, vaginoplasty, and vulvoplasty. While these surgeries can enhance body congruence and relieve gender dysphoria - often with positive effects on sexual functioning - they may also pose anatomical, neurological, and psychosocial challenges. These considerations underscore the need for careful management and realistic preoperative counseling. This review synthesizes the current literature on both positive and negative sexual health outcomes following GAS, identifies gaps in knowledge, and highlights areas for future research aimed at optimizing care for TGD individuals. For the purposes of this paper, sexual health outcomes are defined as outcomes directly affecting the sexual experiences of TGD individuals, including changes in gender dysphoria, factors influencing sexual self-esteem and comfort with intimacy, changes in sensation, and functional changes that affect sexual activity (e.g., the ability to engage in penetrative sex in new ways).

METHODS

This was a narrative review constructed around an outline developed by the two authors, drawing on the senior author’s expertise as a certified sexuality educator and social worker working with patients seeking GAS, as well as her years of experience providing clinical education on TGD sexuality. The literature on each topic was reviewed by both authors using PubMed (primary source) and Google Scholar (secondary source) to identify relevant publications. Where systematic reviews were available, they were considered alongside the primary literature.

SEXUALITY IN TGD PATIENTS

Sexual orientation, sexual attraction, and sexual behavior are distinct constructs and should not be assumed to determine one another, nor should they be presumed on the basis of gender modality - that is, whether a person identifies as cisgender or transgender.

Transgender individuals in the United States report a wide range of sexual orientations, though they are generally less likely to identify as heterosexual than the general population[12-15]. In the 2015 USTS, 21% of respondents identified as queer, 18% as pansexual, 16% as gay/lesbian/same-gender-loving, 15% as straight, 14% as bisexual, and 10% as asexual[16]. Similar distributions were observed in the EU according to the 2019 FRA survey data[17]. Clinicians should also recognize that sexual orientation, attraction, and behavior are not static; they may change over time, including during social, medical, and surgical affirmation[15,18,19]. Sexual histories, when relevant to care, should therefore be reassessed regularly through respectful inquiries about orientation and behavior.

When discussing sexual orientation in the context of surgical assessments, it is critical not to conflate orientation with behavior. Where GAS may affect specific aspects of sexual function (e.g., nipple stimulation, ability to receive or engage in genital penetration), clinicians should ask about patients’ interest in and/or experience with particular behaviors to provide appropriate counseling on possible sexual effects and risks[20].

SEXUAL HEALTH AND FUNCTION IN TGD INDIVIDUALS

The World Health Organization defines sexual health as including “the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences”[21]. This definition extends beyond reproductive rights and the treatment of dysfunction to envision a world where individuals can express their sexuality positively. Achieving sexual health, in this framework, is more comparable to achieving gender euphoria than merely treating gender dysphoria - a positive and affirming goal rather than simply addressing dysfunction[22].

For some individuals, gender-affirming hormones and surgery improve sexual health by alleviating gender dysphoria and allowing them to inhabit a body that feels comfortable and sexually affirming. This may involve both the removal of body parts that are incongruent with self-image and distressing for sexual interaction (e.g., chest masculinization surgery) and the creation of body parts aligned with one’s sexual self-image (e.g., vaginoplasty). Recognizing that gender affirmation can foster greater sexual self-confidence also highlights a fundamental problem with the concept of autogynephilia: it is normal for individuals to have sexual fantasies involving the body in which they feel most comfortable living[23-25].

As with cisgender individuals, TGD individuals display diverse sexual orientations and desires, along with differences in sexual health that may reflect functional concerns as well as experiences of dysphoria and minority stress[26-28]. A large European study reported that the most common sexual dysfunctions among trans women were difficulties initiating sexual activity and achieving orgasm, although overall sexual function generally improved after genital surgery[29]. A review of the literature similarly found that sexual health improved after vaginoplasty, though interpretation is complicated by the lack of standardized outcome measures and the limited number of studies prospectively assessing sexual health prior to surgery[30]. Prospective research is particularly important for determining how presurgical sexual function influences postsurgical outcomes.

Available data suggest that transgender individuals may experience higher rates of sexual dysfunction than the general population prior to genital surgery, and that surgical interventions often improve - but do not fully eliminate- these differences. A 2021 systematic review reported that among transmasculine individuals, hormone therapy generally improved desire and arousal, while surgery had mixed effects on these domains but typically enhanced sexual activity and satisfaction. For transfeminine individuals, hormones showed mixed effects on desire, but surgery consistently increased both arousal and desire[31]. Interpretation remains challenging due to heterogeneity in study designs and outcome measures, as well as variability in dysfunction estimates in both TGD and general populations[32,33].

It is also important to recognize that TGD populations may have higher rates of certain chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, obesity) and behavioral risk factors (e.g., trauma, smoking) that can affect sexual health and function[34-36]. A multidisciplinary approach is therefore valuable during the perioperative process, involving collaboration between surgeons, social workers, behavioral health professionals, and patients’ primary care, mental health, and specialty providers[4,37-39].

EFFECTS OF GENDER-AFFIRMING HORMONAL THERAPY ON SEXUAL FUNCTION

Most individuals who undergo GAS first receive gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT). GAHT is often, though not always, a prerequisite for surgery. Its positive effects are well documented, including improved quality of life (QOL) and reduced depression, anxiety, and suicide risk, and are supported by a growing body of literature and consensus guidelines[3,4,40-46]. Hormone therapy can also influence sexual health and future surgical planning.

Masculinizing hormone therapy typically involves the use of exogenous testosterone in various formulations. Sexual effects - many of which are desirable for some or all patients - include amenorrhea, vaginal atrophy, clitoral enlargement, and increased spontaneous arousal[3,4,47-49]. Vaginal atrophy and clitoral enlargement may become apparent soon after initiation, with peak effects observed after 1-2 years of therapy[49]. Large-scale survey studies also report an association between testosterone use and pelvic pain, particularly with sexual penetration, likely secondary to atrophic changes[50]. For patients with persistent or distressing symptoms related to vaginal atrophy, topical estrogen and/or vaginal moisturizers can be used without significant systemic absorption[51].

Feminizing hormone therapy involves the use of estrogens, often combined with an antiandrogen such as spironolactone or cyproterone acetate (the latter not commonly prescribed in the United States). Some individuals may also receive, or request, adjunctive progesterone. Common sexual effects of estrogen include reduced spontaneous arousal, decreased erectile function, lower semen volume, and testicular atrophy[3,4,49,52]. Patients should be counseled about these potential effects. While some may find them desirable, others may experience them as distressing; in such cases, adjuvant medications or dose adjustments may help[4]. Antiandrogens generally carry sexual effects similar to those of estrogen.

Earlier guidelines recommended perioperative cessation of GAHT for both testosterone and estrogen. However, more recent studies have found no increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or other surgical complications when hormones are continued[53-56]. Moreover, perioperative cessation carries risks of mood disturbance related to hypogonadism. Accordingly, current international guidelines advise against stopping hormones in the perioperative setting[4]. Nevertheless, consensus is lacking, and existing standards of care do not provide a specific recommendation on perioperative hormone use[4]. Surgeons should therefore employ shared decision making with each patient to determine the most appropriate approach.

Gonadotrophin release hormone agonists (GnRHas, or puberty blockers) are prescribed to TGD children at Tanner Stage II to pause the development of secondary sex characteristics, allowing more time for identity exploration and planning for future interventions (e.g., hormone therapy)[3,4]. Importantly, recent studies indicate no evidence of negative impacts of pubertal suppression on long-term sexual health, function, or well-being, while highlighting multiple positive outcomes in these domains[57,58]. It is highly unlikely that a patient would still be on GnRHa therapy at the time of surgery, except potentially as an adjuvant to estrogen therapy as an alternative to other antiandrogens.

SEXUAL HEALTH IMPACTS OF COMMON TYPES OF GAS

Many commonly performed GASs can affect sexual health, both positively and negatively. These include masculinizing chest surgery, feminizing breast augmentation, vaginoplasty, vulvoplasty, phalloplasty, and metoidioplasty (see Table 1 for an overview)[59-62]. Other procedures, such as facial feminization or masculinization surgery, may also enhance sexual well-being indirectly through improvements in body image and sexual self-esteem. This review, however, focuses on surgeries with more direct effects on sexual anatomy and function.

Masculinizing chest surgery

There are numerous surgical techniques for masculinizing chest surgery, including double incision with free nipple graft (the most common technique), inferior pedicled mammaplasty, semicircular, transareolar, concentric circular, and extended concentric circular approaches. A full description of each technique is beyond the scope of this review[63]. The selection of technique depends on surgeon training, patient preferences, and breast characteristics[64]. When patients are appropriately selected, there is no strong evidence suggesting significant differences in sexual health outcomes or subjective satisfaction between techniques, provided surgical complications do not occur[65]. Complications vary by technique but are generally uncommon, including hematoma, seroma, and, more rarely, nipple necrosis or abscess formation[66].

A critical factor influencing both healing and sexual function is the management of the nipple-areolar complex (NAC). Surgeons may leave the NAC largely in place, remove it completely, or modify and reposition it to enhance the masculinized appearance. These decisions are guided by both surgical technique and patient preference. Some individuals may choose to forgo nipples altogether due to concerns about graft healing or aesthetic considerations. Others may prioritize nipple preservation due to its role in sex stimulation and may require more intensive counseling regarding potential surgical effects. Importantly, most individuals undergoing chest masculinization report extreme discomfort with others seeing or touching their unaltered chest[67]. Thus, the key consideration may not be whether patients can retain nipple sensation but whether they can engage in sexual activity involving their chest.

Data on NAC sensory preservation are variable. Small-scale studies report rates of NAC sensation loss ranging from 19.7% to 53.3% in theoretically nipple-sparing procedures (inferior pedicled mammaplasty, semicircular, transareolar, and concentric circular) and from 56.6% to 100% in nipple-grafting procedures (double incision and extended concentric circular)[68-70]. This variability underscores the importance of counseling patients about the risk of sensation loss, which has been linked to reduced sexual arousal and self-esteem in some cases[71].

Despite these differences in sensation outcomes, masculinizing chest surgery generally has strong positive effects on sexual health and overall well-being. An international systematic review (n = 1,052) by

Feminizing breast augmentation

While some transfeminine patients may achieve satisfactory breast development through hormonal therapy alone, many opt for surgical breast augmentation to meet their embodiment goals. Studies estimate that up to 75% of transfeminine patients pursue this option[3,4,9,49,59]. The most common surgical method for breast augmentation in this population involves the use of breast implants. However, there is no standardized or validated approach for selecting implants or determining the placement plane in transfeminine patients. Surgeons generally rely on adapted techniques and tools designed for cisgender patients[59].

The complication rates for breast augmentation in transfeminine patients are low and comparable to those seen in cisgender populations. These complications include symmastia, capsular contracture, altered nipple sensation, implant leakage and migration, hematoma/seroma, and infection[66,72]. Because there is less manipulation of the NAC compared to masculinizing chest surgery, the risk of sensory loss is significantly lower. However, patients should still be counseled about this potential risk and its possible impact on sexual health. Other sensory changes to the chest may also occur after augmentation[59].

As with masculinizing chest surgery, there is substantial evidence showing improved QOL, psychosocial functioning, and sexual health following feminizing breast augmentation. One study, for example, reported more than double the scores for sexual well-being on the BREAST-Q survey after the procedure[6,7,18,73,74].

Vaginoplasty/vulvoplasty

Feminizing genital surgeries, including vaginoplasty and vulvoplasty (collectively referred to as vulvovaginoplasty), have been studied extensively, particularly in the context of sexual health. Unlike other forms of GAS, these procedures typically involve a combination of penectomy, reshaping and relocating the glans to create a sensate clitoris, aesthetic vulva creation, and vaginal formation. However, some individuals seeking feminizing genitoplasty are not interested in vaginal penetration and may choose techniques that do not include the creation of a vagina. These options also avoid the lifelong need for vaginal dilation that follows vaginal vault construction.

Several surgical techniques fall under the umbrella of vaginoplasty. The most commonly reported technique is penile inversion vaginoplasty, which uses penile, scrotal, and perineal skin to line the cavity of the neovagina[4,30,75,76]. Other methods involve tissue from donor sites, such as bowel or peritoneal flaps, which can offer additional benefits, including natural lubrication and varied tissue texture[4,77]. Selection of the technique depends on multiple factors, including the surgeon’s expertise and the patient’s anatomy and embodiment goals, much like gender-affirming chest surgery.

The sexual health benefits of gender-affirming vaginoplasty are well documented. Numerous studies have shown significant improvements in sexual function and satisfaction. These improvements are correlated with factors such as vaginal depth and width, pain levels, ease of orgasm, absence of surgical complications, clitoral sensation, vulvar appearance (especially the ability to “pass” as a cisgender female), and natural lubrication when flaps other than penile skin are used to line the vaginal canal[30,77-79]. Notably, reviews emphasize that “objective” measures of genital sensation (e.g., devices using electrical current or vibration to assess sensitivity thresholds) have no correlation with patients’ self-reported experiences of orgasm, pain, erogenous or tactile sensation, or overall sexual satisfaction.

Achieving orgasm post-vaginoplasty varies across studies, but reviews consistently report that ~80% of patients achieve satisfactory frequency and intensity of orgasm[30,77-79]. This rate is comparable to that of cisgender women, though data are limited[80,81]. Rates of dyspareunia (pain during intercourse) vary between 25%-75%, and this should be addressed during patient counseling. Importantly, transgender women post-vaginoplasty report similar scores on the Female Genital Self-Image Scale (FGSIS) as cisgender women, indicating high levels of body congruence, self-confidence, and sexual satisfaction with genital appearance[79].

A critical area of counseling for potential vaginoplasty patients is the lifelong requirement for dilation if they are not engaging in regular vaginal penetration, as well as douching. Many patients find these activities unpleasant, and for some, this may lead to choosing vulvoplasty instead (sometimes called “zero-depth” vaginoplasty)[77]. Based on clinical experience, the senior author notes that survivors of sexual trauma may face particular difficulties with dilation. Providers should assess whether patients who experience extreme aversion to handling their genitals may struggle with postoperative dilation and hygiene. If concerns arise, patients should engage in presurgical counseling with a knowledgeable therapist to help them manage postoperative care. “Failure to dilate” and “non-adherence to dilation” are frequently cited as key drivers of complications, highlighting the complexity of the procedure and the need for closer collaboration with patients[76,77]. In addition to psychological therapy, pelvic floor physical therapy (PT) referrals may help address both physical and emotional concerns before and after surgery (see The Role of Adjunctive Therapy in Sexual Health After GAS below).

Regarding vulvoplasty, patient satisfaction, including overall QOL and sexual function, is generally high. In one cross-sectional study, a 93% satisfaction rate was reported[77,82]. Over half of the patients who chose vulvoplasty did so without any medical contraindications, highlighting that there are multiple reasons people opt for this procedure. Vulvoplasty is not an inferior procedure to vaginoplasty, nor is it only for those for whom vaginoplasty is medically contraindicated. It is simply a different option.

Phalloplasty/metoidioplasty

The goal of both phalloplasty and metoidioplasty is to create a more masculine genital appearance and function, often including the ability to urinate while standing. For some individuals, this functional aspect is a higher priority than sexual function[83]. Metoidioplasty utilizes the hormonally enlarged clitoris as the body of the phallus, resulting in what is functionally a micropenis. In contrast, phalloplasty creates a larger phallus using a local or distant tissue flap. Both procedures typically involve creating a scrotum, and may also include urethral lengthening and/or vaginectomy (removal of the vagina). Individuals wishing to use their phallus for sexual penetration are generally advised that phalloplasty is the more appropriate procedure, as the phallus length after metoidioplasty is usually insufficient for penetration[84,85].

Gender-affirming phalloplasty is often a multi-staged procedure in which a tissue flap is used to create a neophallus. The specific stages vary depending on the technique and the surgeon’s preference. Commonly used flaps include the radial forearm (RFFF), anterolateral thigh (ATL), and abdominal flaps, though other techniques are occasionally used (albeit less commonly due to higher risks of donor site morbidity)[86].

Both phalloplasty and metoidioplasty may be performed with or without urethral lengthening, depending on whether standing urination is desired[75,86]. While standing urination is a key goal for many individuals seeking masculinizing genitoplasty, it carries significant risks of complications. Indeed, most complications requiring reoperation in both procedures are related to urethral reconstruction, some of which may be acute. Therefore, individuals should consider the tradeoffs between optimizing function and minimizing risks, based on the chosen surgeon and technique[87-90]. Urinary complications may also affect body image and sexual self-esteem, although this has not been specifically studied.

The clitoris is typically either buried within the neophallus or positioned at its base to preserve erogenous sensation. Additionally, some surgeons may incorporate one of the clitoral nerves into the neophallus flap to improve sensation[86]. Overall, most patients (94% in one systematic review) report full tactile sensation in the neophallus, although fewer (~60%) report preserved “erogenous sensation” and sexual function, defined as satisfactory penetrative intercourse[86]. In the same review, the authors reported 97.4% satisfaction with the cosmetic appearance of neophallus constructed using RFFF, with comparable results (> 95%) for abdominal-based approaches. Literature on orgasmic function post-phalloplasty is limited, but one cohort study of 287 RFFF patients found that 100% achieved satisfactory orgasms postoperatively[91].

To achieve sufficient rigidity for sexual penetration after phalloplasty, individuals typically require an erectile device. This is most commonly an internal inflatable prosthesis, though malleable prostheses and other options are also available. Unfortunately, data suggest that failure rates for all types of erectile implants are high, with additional risks of erosion through the neophallus or damage during repair and replacement[92]. These failure rates tend to be higher than those observed with anatomic phalluses, partly due to the lack of the membranes surrounding native erectile tissue, which facilitate device insertion and replacement.

Data on erectile function outcomes with implanted inflatable prostheses is limited, but one systematic review (n = 15 studies) reports 51.4%-90.6% patient satisfaction with erectile function and 77%-100% of patients reporting the ability to engage in penetrative intercourse. In general, sexual health outcomes are underreported for phalloplasty, with one recent review noting that they are documented in fewer than half of the relevant studies[93]. More research is needed to better understand these outcomes.

Patients considering phalloplasty often inquire about ejaculatory function. Although ejaculation is not expected after neophallus construction, some patients report experiencing it in community forums, and patient-facing resources from surgical clinics suggest rates of around 10%[94,95]. However, literature on this topic is sparse, and it is likely that any ejaculated fluid consists primarily of urine, given the anatomical changes involved. Future research should aim to clarify this outcome, and surgeons performing phalloplasty should assess and document it during follow-up visits.

Sexual health outcomes for metoidioplasty are also under-researched. One systematic review (n = 14 studies, 1,455 cases) reported high satisfaction rates and low regret rates. Notably, 100% of patients reported fully preserved erogenous sensation, and 66%-77% retained orgasmic function during intercourse (100% with masturbation). However, 87%-100% of patients reported an inability to engage in penetrative sex due to the anatomy of the microphallus[96]. As such, metoidioplasty is generally recommended only for individuals who do not desire penetrative sex.

Testicular prostheses are typically implanted in the constructed scrotum during phalloplasty or metoidioplasty as part of the staged procedure. The insertion of testicular prostheses is generally considered low-risk, although complications like migration and erosion can occur[97-99]. Based on research in cisgender men, testicular prostheses could potentially improve sexual function by alleviating gender dysphoria and boosting sexual self-confidence in those who have undergone genital affirmation surgery. However, we found no research on the effects of testicular prostheses on sexual well-being in transgender men[100,101]. See Table 2 for a summary of how various GASs may affect sexual health.

Potential mechanisms for sexual health effects of gender-affirming surgical procedures, and the level of evidentiary support

| Procedure | Potential mechanisms for sexual health effects | Evidence for sexual health effects | |

| Feminizing procedures | Breast augmentation | Increased sexual self-confidence Improved gender dysphoria Chest/breast sensation changes may affect sexual interactions Nipple sensation/function changes depending on surgical technique | Limited evidence, with one prospective study[73,102,103] |

| Vaginoplasty | Enables gender-congruent sexual activities involving the vagina/clitoris Improved gender dysphoria Possible discomfort related to visible scarring or the aesthetics of external genitalia Risk of dyspareunia and/or pelvic floor dysfunction with sexual penetration and/or dilation Changes in experiences of orgasm | Numerous studies report positive sexual outcomes, including preserved ability to orgasm and clitoral sensation. However, the scope of studied sexual function could be expanded[24,30,102,104-117] | |

| Vulvoplasty | As above, without the possibility of vaginal penetration | Sexual effects are not as well studied, but likely offer similar benefits to vaginoplasty for individuals not interested in vaginal penetration[108,118,119] | |

| Orchiectomy | Reduced medication needs and associated side effects Improved gender dysphoria | Not well studied as a standalone procedure in this context[120] | |

| FFS and tracheal shave | Increased appearance congruence may enhance sexual self-confidence. Facial sensation changes could potentially affect kissing and intimacy, depending on the extent of surgery | Sexual effects have not been studied[102] | |

| Masculinizing chest surgery | Improved sexual self-confidence and reduced anxiety about showing the chest and being touched Improved gender dysphoria Altered or lost nipple sensation/function (may or may not affect sexuality) | Numerous cross-sectional, retrospective and prospective studies address sexuality at least peripherally[67,103,121-125] | |

| Masculinizing procedures | Hysterectomy | Improved gender dysphoria, particularly regarding menstrual bleeding, may increase sexual self-confidence Pelvic floor function changes may affect sexuality in some individuals | Sexual effects have not yet been studied in transgender populations. Mixed evidence exists regarding sexual effects in cisgender women undergoing a benign hysterectomy[102,126-129] |

| Metoidioplasty (including testicular prostheses) | Allows for gender-congruent sexual activities involving the phallus/scrotum Improved gender dysphoria Possible discomfort related to visible scarring or the aesthetics of external genitalia Changes in experiences of orgasm Concerns about urinary function affecting sexuality Insufficient length for penetrative sex may lead some individuals to eventually choose conversion to phalloplasty | Moderate evidence of improvements in sexual function. Many individuals, though not all, report orgasm and satisfactory sexual function post-surgery. Studies indicate higher satisfaction with metoidioplasty than phalloplasty for those not interested in penetration[85,87,89,102,130-136] | |

| Phalloplasty (inclusive of testicular/ erectile prostheses) | All concerns listed for metoidioplasty, plus: Concerns about functional issues with erection and penetration; Sensation concerns in the neophallus; Worries about complications; Potential need for revision surgery for urinary or erectile function | Mixed data on sexual function. Sexual satisfaction and the ability to orgasm are common but not universal. Lower satisfaction is often linked to complications and problems with penetration[87,87,102,107,133,137-142] | |

THE ROLE OF ADJUVANT THERAPIES IN SEXUAL HEALTH AFTER GAS

Pelvic floor PT may be beneficial in supporting GAS patients throughout the perioperative period. In a systematic review and meta-analysis (n = 25 studies, 8,566 cases), Dominoni et al. observed variable rates of pelvic floor dysfunction following gender-affirming genital surgery[111]. Among transgender women who underwent vaginoplasty, pelvic organ prolapse occurred in 1%-7.5% of cases, urinary incontinence in 15%, irritative urinary symptoms (such as urgency, frequency, and nocturia) in 20%, and sexual dysfunction of varying severity in 25%-75%. Among transgender men who underwent phalloplasty with hysterectomy, pelvic organ prolapse was reported in 3.8% of patients, urinary incontinence in 50%, irritative urinary symptoms in 37%, and sexual dysfunction in 54%. Only four of the studies reviewed addressed the efficacy of pelvic floor therapy in alleviating these symptoms. Attendance at pelvic floor PT both pre- and postoperatively was significantly associated with lower rates of pelvic floor dysfunction compared to postoperative therapy alone. Moreover, postoperative PT led to significant improvements in pelvic floor dysfunction among patients who screened positive for symptoms prior to surgery. Therefore, it is important to screen patients for preoperative pelvic floor dysfunction and counsel them on the associated risks. Surgeons should consider referring patients to pelvic floor PT if preoperative symptoms are present or if symptoms develop/worsen postoperatively.

Behavioral health providers also play an important role in supporting the sexual health and function of individuals undergoing GAS throughout the perioperative period. As part of a multidisciplinary team, they are often involved in assessing patients’ psychosocial readiness for surgery, addressing both practical concerns (e.g., housing, postoperative support) and mental health (e.g., PTSD that may affect the ability to dilate after vaginoplasty). They may also assist with writing the letters of support required for insurance coverage[37,143,144]. Additionally, they may work with patients in the preoperative period to develop coping strategies and other skills to enhance readiness for surgery. After the procedure, they continue to provide mental health support and counseling on various psychosocial concerns, including sexual health. Transgender-informed sex therapists can be especially helpful for individuals experiencing sexual health concerns or dysfunction in the postoperative period, including helping patients navigate how to have a fulfilling sexual life in the context of surgical complications[79,145].

CONCLUSION

GAS is a critical aspect of care for many TGD individuals, significantly influencing sexual health, psychosocial functioning, and overall QOL. The existing literature supports the numerous benefits of GAS (including improved body image/self-esteem, increased sexual function and satisfaction, and reduced gender dysphoria). However, it also highlights the need for appropriate, comprehensive preoperative counseling, which should include discussion about sexual health goals and anticipated outcomes.

This study is limited by its narrative structure rather than being a systematic review, and it is further constrained by the absence of systematically collected sexual outcome data for TGD individuals undergoing GAS[102]. Despite significant advances in surgical techniques and increased research focus on TGD populations, a major limitation remains the lack of validated, population-specific outcome measures to assess the impact of GAC on TGD patients’ health, particularly sexual health. While no measures currently exist that have been well validated or specifically developed for TGD populations, such tools are in development. For example, the GENDER-Q, a patient-reported outcome measure specifically for GAC outcomes, published its initial validation study in April 2025[146]. Incorporating validated measures like the GENDER-Q into future research and clinical practice will improve the quality and comparability of outcome data and ensure that patient voices are meaningfully integrated into care.

As the demand for GAS continues to grow, physicians and researchers must focus on outcomes that matter most to patients. These include not only the technical success of surgical procedures but also long-term sexual well-being, relational intimacy, and psychosocial flourishing. Such goals are highly individual and require intentional assessment to determine whether they are realistic and aligned with the surgical plan. Sexual health should not be viewed as a peripheral concern - it is a central dimension of human health and dignity. Therefore, it must be: (1) treated as a core outcome in both research and clinical care; (2) integrated into our broader understanding of QOL; and (3) supported with the same rigor and empathy applied to other domains of health. To achieve this, improved training is needed across both undergraduate and graduate medical curricula to enhance provider competency and comfort in engaging in affirming, informed discussions about sexuality and health[147,148]. For this training to be effective, it must go beyond the discreet effects of surgery on sexual function and explore the broader ways in which physical and mental health, as well as the social environment, contribute to sexual health - not only for TGD individuals but for the population as a whole[21,149-152].

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to the conceptualization, wrote the first draft, and assisted with editing: Billings HM

Made substantial contributions to the conceptualization and edited and revised the manuscript for publication: Boskey ER

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Boskey ER is a Junior Editorial Board member of the journal Plastic and Aesthetic Research. Boskey ER was not involved in any steps of editorial processing, notably including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision making. Billings HM declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Sexual health. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/sexual-health#tab=tab_1. [Last accessed on 25 Aug 2025].

2. Özer M, de Kruif AJTCM, Gijs LACL, Kreukels BPC, Mullender MG. Sexual wellbeing according to transgender individuals. Int J Sex Health. 2023;35:608-24.

3. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3869-903.

4. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23:S1-259.

5. Park RH, Liu YT, Samuel A, et al. Long-term outcomes after gender-affirming surgery: 40-year follow-up study. Ann Plast Surg. 2022;89:431-6.

6. Wernick JA, Busa S, Matouk K, Nicholson J, Janssen A. A systematic review of the psychological benefits of gender-affirming surgery. Urol Clin North Am. 2019;46:475-86.

7. Almazan AN, Keuroghlian AS. Association between gender-affirming surgeries and mental health outcomes. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:611-8.

8. Herman JL, Flores AR, O’Niel KK. How Many Adults and Youth Identify as Transgender in the United States. Available from: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Trans-Pop-Update-Jun-2022.pdf. [Last accessed on 25 Aug 2025].

9. Rastogi A, Menard L, Miller GH, Cole W, Laurison D, Caballero J, Heng-Lehtinen R. Health and wellbeing: a report of the 2022 U.S. transgender survey. Available from: https://ustranssurvey.org/download-reports/. [Last accessed on 25 Aug 2025].

10. Fundamental Rights Agency. Share of transgender survey respondents having undergone surgery in order to change their body in a way that better matches their gender identity in Europe in 2019, by country. Available from: https://www-statista-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/statistics/1383064/lgbtq-europe-gender-affirming-surgery/. [Last accessed on 25 Aug 2025].

11. Shah V, Hassan B, Hassan R, et al. Gender-affirming surgery in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2024;13:3580.

12. Nieder TO, Elaut E, Richards C, Dekker A. Sexual orientation of trans adults is not linked to outcome of transition-related health care, but worth asking. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28:103-11.

13. Katz-Wise SL, Reisner SL, Hughto JW, Keo-Meier CL. Differences in sexual orientation diversity and sexual fluidity in attractions among gender minority adults in massachusetts. J Sex Res. 2016;53:74-84.

14. Galupo MP, Henise SB, Mercer NL. “The labels don’t work very well”: transgender individuals’ conceptualizations of sexual orientation and sexual identity. Int J Transgend. 2016;17:93-104.

15. Auer MK, Fuss J, Höhne N, Stalla GK, Sievers C. Transgender transitioning and change of self-reported sexual orientation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110016.

16. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. Available from: https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf. [Last accessed on 25 Aug 2025].

17. Russell CB, Sanders F, Watkins F. Diving into the FRA LGBTI II survey data: trans and non-binary briefing. Available from: https://www.ilga-europe.org/files/uploads/2023/07/FRA-Intersections-Report-Trans-Non-binary.pdf. [Last accessed on 25 Aug 2025].

18. Özer M, Toulabi SP, Fisher AD, et al. ESSM position statement “sexual wellbeing after gender affirming surgery”. Sex Med. 2022;10:100471.

19. Defreyne J, Elaut E, Den Heijer M, Kreukels B, Fisher AD, T’Sjoen G. Sexual orientation in transgender individuals: results from the longitudinal ENIGI study. Int J Impot Res. 2020;33:694-702.

20. Jolly D, Boskey ER, Thomson KA, Tabaac AR, Burns MTS, Katz-Wise SL. Why are you asking? J Adolesc Health. 2021;69:891-3.

21. World Health Organization. Sexual health, human rights and the law. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/175556. [Last accessed on 25 Aug 2025].

22. Beischel WJ, Gauvin SEM, van Anders SM. “A little shiny gender breakthrough”: community understandings of gender euphoria. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23:274-94.

24. Kloer C, Blasdel G, Shakir N, et al. Does genital self-image correspond with sexual health before and after vaginoplasty? Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11:e4806.

25. Holmberg M, Arver S, Dhejne C. Supporting sexuality and improving sexual function in transgender persons. Nat Rev Urol. 2019;16:121-39.

26. Bauer GR, Redman N, Bradley K, Scheim AI. Sexual health of trans men who are gay, bisexual, or who have sex with men: results from Ontario, Canada. Int J Transgend. 2013;14:66-74.

27. Dharma C, Scheim AI, Bauer GR. Exploratory factor analysis of two sexual health scales for transgender people: trans-specific condom/barrier negotiation self-efficacy (T-barrier) and trans-specific sexual body image worries (T-worries). Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48:1563-72.

28. Gil-Llario MD, Gil-Juliá B, Giménez-García C, Bergero-Miguel T, Ballester-Arnal R. Sexual behavior and sexual health of transgender women and men before treatment: Similarities and differences. Int J Transgend Health. 2021;22:304-15.

29. Kerckhof ME, Kreukels BPC, Nieder TO, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions in transgender persons: results from the ENIGI follow-up study. J Sex Med. 2019;16:2018-29.

30. Kloer C, Parker A, Blasdel G, Kaplan S, Zhao L, Bluebond-Langner R. Sexual health after vaginoplasty: a systematic review. Andrology. 2021;9:1744-64.

31. Mattawanon N, Charoenkwan K, Tangpricha V. Sexual dysfunction in transgender people: a systematic review. Urol Clin North Am. 2021;48:437-60.

32. McCool ME, Zuelke A, Theurich MA, Knuettel H, Ricci C, Apfelbacher C. Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction among premenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sex Med Rev. 2016;4:197-212.

33. Ramírez-Santos J, Cristóbal-Cañadas D, Parron-Carreño T, Lozano-Paniagua D, Nievas-Soriano BJ. The problem of calculating the prevalence of sexual dysfunction: a meta-analysis attending gender. Sex Med Rev. 2024;12:116-26.

34. Rich AJ, Scheim AI, Koehoorn M, Poteat T. Non-HIV chronic disease burden among transgender populations globally: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Prev Med Rep. 2020;20:101259.

35. Knaus S, Steininger J, Klinger D, Riedl S. Body mass index distributions and obesity prevalence in a transgender youth cohort - a retrospective analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2024;75:127-32.

36. Brown J, Pfeiffer RM, Shrewsbury D, et al. Prevalence of cancer risk factors among transgender and gender diverse individuals: a cross-sectional analysis using UK primary care data. Br J Gen Pract. 2023;73:e486-92.

37. Roblee C, Hamidian Jahromi A, Ferragamo B, et al. Gender-affirmative surgery: a collaborative approach between the surgeon and mental health professional. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;152:953e-61.

38. Deutsch MB. Gender-affirming surgeries in the era of insurance coverage: developing a framework for psychosocial support and care navigation in the perioperative period. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27:386-91.

39. Selvaggi G, Giordano S. The role of mental health professionals in gender reassignment surgeries: unjust discrimination or responsible care? Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:1177-83.

40. T'Sjoen G, Arcelus J, De Vries ALC, et al. European Society for Sexual Medicine position statement “Assessment and hormonal management in adolescent and adult trans people, with attention for sexual function and satisfaction”. J Sex Med. 2020;17:570-84.

41. Baker KE, Wilson LM, Sharma R, Dukhanin V, McArthur K, Robinson KA. Hormone therapy, mental health, and quality of life among transgender people: a systematic review. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5:bvab011.

42. Reisner SL, Pletta DR, Keuroghlian AS, et al. Gender-affirming hormone therapy and depressive symptoms among transgender adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e250955.

43. Turban JL, King D, Kobe J, Reisner SL, Keuroghlian AS. Access to gender-affirming hormones during adolescence and mental health outcomes among transgender adults. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0261039.

44. Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, Stepney C, Inwards-Breland DJ, Ahrens K. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e220978.

45. Chen D, Berona J, Chan YM, et al. Psychosocial functioning in transgender youth after 2 years of hormones. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:240-50.

46. Green AE, DeChants JP, Price MN, Davis CK. Association of gender-affirming hormone therapy with depression, thoughts of suicide, and attempted suicide among transgender and nonbinary youth. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70:643-9.

47. Fisher AD, Castellini G, Ristori J, et al. Cross-sex hormone treatment and psychobiological changes in transsexual persons: two-year follow-up data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:4260-9.

48. Defreyne J, Elaut E, Kreukels B, et al. Sexual desire changes in transgender individuals upon initiation of hormone treatment: results from the longitudinal european network for the investigation of gender incongruence. J Sex Med. 2020;17:812-25.

49. T'Sjoen G, Arcelus J, Gooren L, Klink DT, Tangpricha V. Endocrinology of transgender medicine. Endocr Rev. 2019;40:97-117.

50. Tordoff DM, Lunn MR, Chen B, et al. Testosterone use and sexual function among transgender men and gender diverse people assigned female at birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;229:669.e1-17.

51. Deutsch M. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. Available from: https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines. [Last accessed on 25 Aug 2025].

52. Adeleye AJ, Reid G, Kao CN, Mok-Lin E, Smith JF. Semen parameters among transgender women with a history of hormonal treatment. Urology. 2019;124:136-41.

53. Kozato A, Fox GWC, Yong PC, et al. No venous thromboembolism increase among transgender female patients remaining on estrogen for gender-affirming surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:e1586-90.

54. Wu SS, Raymer CA, Kaufman BR, Isakov R, Ferrando CA. The effect of preoperative gender-affirming hormone therapy use on perioperative adverse events in transmasculine individuals undergoing masculinizing chest surgery for gender affirmation. Aesthet Surg J. 2022;42:1009-16.

55. Rysin R, Skorochod R, Wolf Y. Implications of testosterone therapy on wound healing and operative outcomes of gender-affirming chest masculinization surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2023;81:34-41.

56. Robinson IS, Rifkin WJ, Kloer C, et al. Perioperative hormone management in gender-affirming mastectomy: is stopping testosterone before top surgery really necessary? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;151:421-7.

57. Finegan JL, Marinkovic M, Okamuro K, Newfield RS, Anger JT. Experience with gender affirming hormones and puberty blockers (gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist): a qualitative analysis of sexual function. J Sex Med. 2025;22:945-50.

58. van der Meulen IS, Bungener SL, van der Miesen AIR, et al. Timing of puberty suppression in transgender adolescents and sexual functioning after vaginoplasty. J Sex Med. 2025;22:196-204.

59. Bekeny JC, Zolper EG, Fan KL, Del Corral G. Breast augmentation for transfeminine patients: methods, complications, and outcomes. Gland Surg. 2020;9:788-96.

60. Morrison SD, Wilson SC, Mosser SW. Breast and body contouring for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. Clin Plast Surg. 2018;45:333-42.

61. Fisher M, Lu SM, Chen K, Zhang B, Di Maggio M, Bradley JP. Facial feminization surgery changes perception of patient gender. Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40:703-9.

62. Boskey ER, Mehra G, Jolly D, Ganor O. Concerns about internal erectile prostheses among transgender men who have undergone phalloplasty. J Sex Med. 2022;19:1055-9.

63. Hale ES, Gibstein AR, Smartz T, Boghosian T, Jabori SK, Danker S. Chest feminization and masculinization surgery: part two of the plastic surgeon's perspective of gender-affirming surgery. Plast Aesthet Nurs. 2025;45:27-33.

64. Wolf Y, Kwartin S. Classification of transgender man’s breast for optimizing chest masculinizing gender-affirming surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9:e3363.

65. Bustos VP, Bustos SS, Mascaro A, et al. Transgender and gender-nonbinary patient satisfaction after transmasculine chest surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9:e3479.

66. Claes KEY, D’Arpa S, Monstrey SJ. Chest surgery for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. Clin Plast Surg. 2018;45:369-80.

67. Olson-Kennedy J, Warus J, Okonta V, Belzer M, Clark LF. Chest reconstruction and chest dysphoria in transmasculine minors and young adults: comparisons of nonsurgical and postsurgical cohorts. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:431-6.

68. Knox ADC, Ho AL, Leung L, et al. A review of 101 consecutive subcutaneous mastectomies and male chest contouring using the concentric circular and free nipple graft techniques in female-to-male transgender patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:1260e-72.

69. Wolter A, Diedrichson J, Scholz T, Arens-Landwehr A, Liebau J. Sexual reassignment surgery in female-to-male transsexuals: an algorithm for subcutaneous mastectomy. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:184-91.

70. Nelson L, Whallett EJ, McGregor JC. Transgender patient satisfaction following reduction mammaplasty. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:331-4.

71. Rochlin DH, Brazio P, Wapnir I, Nguyen D. Immediate targeted nipple-areolar complex reinnervation: improving outcomes in gender-affirming mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8:e2719.

72. Kanhai RC, Hage JJ, Asscheman H, Mulder JW. Augmentation mammaplasty in male-to-female transsexuals. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:542-9.

73. Weigert R, Frison E, Sessiecq Q, Al Mutairi K, Casoli V. Patient satisfaction with breasts and psychosocial, sexual, and physical well-being after breast augmentation in male-to-female transsexuals. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:1421-9.

74. Oles N, Darrach H, Landford W, et al. Gender affirming surgery: a comprehensive, systematic review of all peer-reviewed literature and methods of assessing patient-centered outcomes (Part 1: Breast/chest, face, and voice). Ann Surg. 2022;275:e52-66.

75. Grimstad F, Guss C. Medical and surgical reproductive care of transgender and gender diverse patients. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2024;51:621-33.

76. Hontscharuk R, Alba B, Hamidian Jahromi A, Schechter L. Penile inversion vaginoplasty outcomes: complications and satisfaction. Andrology. 2021;9:1732-43.

77. Morrison SD, Claes K, Morris MP, Monstrey S, Hoebeke P, Buncamper M. Principles and outcomes of gender-affirming vaginoplasty. Nat Rev Urol. 2023;20:308-22.

78. Wilder S, Shannon B, Blasdel G, Shakir N. Sexual function outcomes following gender-affirming vaginoplasty: a literature review. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2023;15:301-6.

79. Schardein JN, Nikolavsky D. Sexual functioning of transgender females post-vaginoplasty: evaluation, outcomes and treatment strategies for sexual dysfunction. Sex Med Rev. 2022;10:77-90.

80. Ishak WW, Bokarius A, Jeffrey JK, Davis MC, Bakhta Y. Disorders of orgasm in women: a literature review of etiology and current treatments. J Sex Med. 2010;7:3254-68.

81. Goldmeier D, Keane FE, Carter P, Hessman A, Harris JR, Renton A. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in heterosexual patients attending a central London genitourinary medicine clinic. Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8:303-6.

83. Ganor O, Taghinia AH, Diamond DA, Boskey ER. Piloting a genital affirmation surgical priorities scale for trans masculine patients. Transgend Health. 2019;4:270-6.

84. Frey JD, Poudrier G, Chiodo MV, Hazen A. A systematic review of metoidioplasty and radial forearm flap phalloplasty in female-to-male transgender genital reconstruction: is the “ideal” neophallus an achievable goal? Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4:e1131.

85. Djordjevic ML, Stanojevic D, Bizic M, et al. Metoidioplasty as a single stage sex reassignment surgery in female transsexuals: Belgrade experience. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1306-13.

86. Alba B, Nolan IT, Weinstein B, et al. Gender-affirming phalloplasty: a comprehensive review. J Clin Med. 2024;13:5972.

87. de Rooij FPW, van de Grift TC, Veerman H, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after genital gender-affirming surgery with versus without urethral lengthening in transgender men. J Sex Med. 2021;18:974-81.

88. Veerman H, de Rooij FPW, Al-Tamimi M, et al. Functional outcomes and urological complications after genital gender affirming surgery with urethral lengthening in transgender men. J Urol. 2020;204:104-9.

89. Pigot GLS, Al-Tamimi M, Nieuwenhuijzen JA, et al. Genital gender-affirming surgery without urethral lengthening in transgender men-a clinical follow-up study on the surgical and urological outcomes and patient satisfaction. J Sex Med. 2020;17:2478-87.

90. van de Grift TC, Pigot GLS, Boudhan S, et al. A longitudinal study of motivations before and psychosexual outcomes after genital gender-confirming surgery in transmen. J Sex Med. 2017;14:1621-8.

91. Monstrey S, Hoebeke P, Selvaggi G, et al. Penile reconstruction: is the radial forearm flap really the standard technique? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:510-8.

92. Pang KH, Christopher N, Ralph DJ, Lee WG. Insertion of inflatable penile prosthesis in the neophallus of assigned female at birth individuals: a systematic review of surgical techniques, complications and outcomes. Ther Adv Urol. 2023;15:17562872231199584.

93. Zhang X, Neuville P, Skokan AJ. Sexual health in transgender and gender diverse people. Curr Opin Urol. 2024;34:330-5.

94. Gender Confirmation Center. Phalloplasty: gender-affirming bottom surgery. Available from: https://www.genderconfirmation.com/bottom-surgery-ftm-phalloplasty. [Last accessed on 25 Aug 2025].

95. GrS Montreal. Frequently asked questions. Available from: https://www.grsmontreal.com/en/frequently-asked-questions/6-phalloplasty.html. [Last accessed on 25 Aug 2025].

96. Dolendo I, Goldstein B, Okamuro K, Peters B, Anger J, Uloko M. (345) Sexual health outcomes after gender affirming metoidioplasty: a systematic review. J Sex Med. 2024;21:qdae001.330.

97. Briles B, Crane C, Santucci R. Long-term fate of testis prosthesis after metoidioplasty and phalloplasty. Urology. 2025;197:190-2.

98. Ho P, Schmidt-Beuchat E, Sljivich M, Djordjevic M, Nyein E, Purohit RS. Testicular implant complications after transmasculine gender affirming surgery. Int Braz J Urol. 2025;51:e20240427.

99. Legemate CM, de Rooij FPW, Bouman MB, Pigot GL, van der Sluis WB. Surgical outcomes of testicular prostheses implantation in transgender men with a history of prosthesis extrusion or infection. Int J Transgend Health. 2021;22:330-6.

100. Fascelli M, Hennig F, Dy GW. Penile and testicular prosthesis following gender-affirming phalloplasty and scrotoplasty: a narrative review and technical insights. Transl Androl Urol. 2023;12:1568-80.

101. Pigot GLS, Al-Tamimi M, Ronkes B, et al. Surgical outcomes of neoscrotal augmentation with testicular prostheses in transgender men. J Sex Med. 2019;16:1664-71.

102. Özer M, Toulabi SP, Fisher AD, et al. ESSM position statement “Sexual wellbeing after gender affirming surgery. Sex Med. 2021;10:100471.

103. Schoulepnikoff C, Bauquis O, di Summa PG. Impact of gender-confirming chest surgery on sexual health: a prospective study. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:e6014.

104. Vazquez I, Labanca T, Arno AI. Functional, aesthetic, and sensory postoperative complications of female genital gender affirmation surgery: a prospective study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2022;75:4312-20.

105. Raigosa M, Avvedimento S, Yoon TS, Cruz-Gimeno J, Rodriguez G, Fontdevila J. Male-to-female genital reassignment surgery: a retrospective review of surgical technique and complications in 60 patients. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1837-45.

106. Jerome RR, Randhawa MK, Kowalczyk J, Sinclair A, Monga I. Sexual satisfaction after gender affirmation surgery in transgender individuals. Cureus. 2022;14:e27365.

107. Schoenbrunner A, Cripps C. Sexual function in post-surgical transgender and gender diverse individuals. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2024;51:425-35.

108. Garcia MM. Sexual function after shallow and full-depth vaginoplasty: challenges, clinical findings, and treatment strategies- urologic perspectives. Clin Plast Surg. 2018;45:437-46.

109. Ramsay A, Blankson J, Finnerty-Haggerty L, Wu J, Safer JD, Pang JH. Using a novel and validated survey tool to analyze sexual functioning following vaginoplasty in transgender individuals. Sex Health. 2025;22:SH24070.

110. Kitic A, Pozzo V, Kitic N, Atlan M, Rausky J. Impact of vaginoplasty on sexual health and satisfaction in transgender women. J Sex Med. 2025;22:536-42.

111. Dominoni M, Scatigno AL, Pasquali MF, Bergante C, Gariboldi F, Gardella B. Pelvic floor and sexual dysfunctions after genital gender-affirming surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2025;22:184-95.

112. Litrico L, Van Dieren L, Cetrulo CL Jr, Atlan M, Lellouch AG, Cristofari S. Improved sexuality and satisfactory lubrication after genital affirmation surgery using penile skin inversion in transgender women: a satisfaction study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2023;86:8-14.

113. Potter E, Sivagurunathan M, Armstrong K, et al. Patient reported symptoms and adverse outcomes seen in Canada’s first vaginoplasty postoperative care clinic. Neurourol Urodyn. 2023;42:523-9.

114. Zavlin D, Schaff J, Lellé JD, et al. Male-to-female sex reassignment surgery using the combined vaginoplasty technique: satisfaction of transgender patients with aesthetic, functional, and sexual outcomes. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42:178-87.

115. LeBreton M, Courtois F, Journel NM, et al. Genital sensory detection thresholds and patient satisfaction with vaginoplasty in male-to-female transgender women. J Sex Med. 2017;14:274-81.

116. Buncamper ME, Honselaar JS, Bouman MB, Özer M, Kreukels BP, Mullender MG. Aesthetic and functional outcomes of neovaginoplasty using penile skin in male-to-female transsexuals. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1626-34.

117. Horbach SE, Bouman MB, Smit JM, Özer M, Buncamper ME, Mullender MG. Outcome of vaginoplasty in male-to-female transgenders: a systematic review of surgical techniques. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1499-512.

118. van der Sluis WB, Steensma TD, Timmermans FW, et al. Gender-confirming vulvoplasty in transgender women in the netherlands: incidence, motivation analysis, and surgical outcomes. J Sex Med. 2020;17:1566-73.

119. Stelmar J, Smith SM, Lee G, Zaliznyak M, Garcia MM. Shallow-depth vaginoplasty: preoperative goals, postoperative satisfaction, and why shallow-depth vaginoplasty should be offered as a standard feminizing genital gender-affirming surgery option. J Sex Med. 2023;20:1333-43.

120. Stelmar J, Victor R, Yuan N, et al. Endocrine, gender dysphoria, and sexual function benefits of gender-affirming bilateral orchiectomy: patient outcomes and surgical technique. Sex Med. 2024;12:qfae048.

121. Roblee CV, Arteaga R, Taritsa I, et al. Patient-reported and clinical outcomes following gender-affirming chest surgery: a comparison of binary and nonbinary transmasculine individuals. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:e6297.

122. Kanlagna A, Oillic J, Verdier J, Perrot P, Lancien U. Prospective assessment of the quality of life and nipple sensation after gender-affirming chest surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2024;94:46-9.

123. Bertrand AA, DeLong MR, McCleary SP, et al; Plastic Surgery Research Group. Gender-affirming mastectomy: psychosocial and surgical outcomes in transgender adults. J Am Coll Surg. 2024;238:890-9.

124. Poudrier G, Nolan IT, Cook TE, et al. Assessing quality of life and patient-reported satisfaction with masculinizing top surgery: a mixed-methods descriptive survey study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:272-9.

125. Agarwal CA, Scheefer MF, Wright LN, Walzer NK, Rivera A. Quality of life improvement after chest wall masculinization in female-to-male transgender patients: a prospective study using the BREAST-Q and body uneasiness test. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2018;71:651-7.

126. Forsgren C, Johannesson U. Sexual function and pelvic floor function five years after hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2025;104:948-57.

127. Ouyang C, Wang A, Briggs M, et al. Changes in sexual function after minimally invasive hysterectomy in reproductive-aged women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2025;Epub ahead of print.

128. Ferhi M, Marwen N, Abdeljabbar A, Mannai J. To preserve or not to preserve: a prospective cohort study on the role of the cervix in post-hysterectomy sexual functioning. Cureus. 2024;16:e68876.

129. Kazemi F, Alimoradi Z, Tavakolian S. Effect of hysterectomy due to benign diseases on female sexual function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29:476-88.

130. Djordjevic ML, Bizic MR. Comparison of two different methods for urethral lengthening in female to male (metoidioplasty) surgery. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1431-8.

131. Stojanovic B, Bizic M, Bencic M, et al. One-stage gender-confirmation surgery as a viable surgical procedure for female-to-male transsexuals. J Sex Med. 2017;14:741-6.

132. Djordjevic ML. Novel surgical techniques in female to male gender confirming surgery. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7:628-38.

133. de Grift TC, Pigot GLS, Kreukels BPC, Bouman MB, Mullender MG. Transmen’s experienced sexuality and genital gender-affirming surgery: findings from a clinical follow-up study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2019;45:201-5.

134. Takamatsu A, Harashina T. Labial ring flap: a new flap for metaidoioplasty in female-to-male transsexuals. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:318-25.

135. Vukadinovic V, Stojanovic B, Majstorovic M, Milosevic A. The role of clitoral anatomy in female to male sex reassignment surgery. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:437378.

136. Bordas N, Stojanovic B, Bizic M, Szanto A, Djordjevic ML. Metoidioplasty: surgical options and outcomes in 813 cases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:760284.

137. Elfering L, van de Grift TC, Al-Tamimi M, et al. How sensitive is the neophallus? Sex Med. 2021;9:100413.

138. Rooker SA, Vyas KS, DiFilippo EC, Nolan IT, Morrison SD, Santucci RA. The rise of the neophallus: a systematic review of penile prosthetic outcomes and complications in gender-affirming surgery. J Sex Med. 2019;16:661-72.

139. Remington AC, Morrison SD, Massie JP, et al. Outcomes after phalloplasty: do transgender patients and multiple urethral procedures carry a higher rate of complication? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:220e-9.

140. Papadopulos NA, Ehrenberger B, Zavlin D, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction in transgender men after phalloplasty in a retrospective study. Ann Plast Surg. 2021;87:91-7.

141. Monchablon B, Morel-Journel N, Carnicelli D, Jurek L, Ruffion A, Neuville P. Surgical outcomes, motivations, sexuality, and urinary function of metoidioplasty with semi-rigid prosthesis. Int J Transgend Health. 2025;26:63-72.

142. Akhoondinasab MR, Saraee A, Forghani SF, Mousavi A, Shahrbaf MA. Comparison of the results of phalloplasty using radial free forearm flap and anterolateral thigh in Iran from 2014 to 2019. Indian J Plast Surg. 2024;57:387-93.

143. Quint M, Bailar S, Miranda A, Bhasin S, O’Brien-Coon D, Reisner SL. The AFFIRM framework for gender-affirming care: qualitative findings from the transgender and gender diverse health equity study. BMC Public Health. 2025;25:491.

144. Mehra G, Boskey ER, Ganor O. The quality and utility of referral letters for gender-affirming surgery. Transgend Health. 2022;7:497-504.

145. Holmberg M, Arver S, Dhejne C. Improving sexual function and pleasure in transgender persons. In: Hall K, Binik Y, Editors. Principles and practice of sex therapy. The Guilford Press; 2020. pp. 423-52. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=T0fNDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA423&dq=Improving+sexual+function+and+pleasure+in+transgender+persons&ots=uRGkD9faBy&sig=WE7Jh_6DjzeRmL9HD-mOMFtFgVg#v=onepage&q=Improving%20sexual%20function%20and%20pleasure%20in%20transgender%20persons&f=false. [Last accessed on 25 Aug 2025].

146. Kaur MN, Rae C, Morrison SD, et al. Development and assessment of a patient-reported outcome instrument for gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e254708.

147. O’Farrell M, Corcoran P, Davoren MP. Examining LGBTI+ inclusive sexual health education from the perspective of both youth and facilitators: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e047856.

148. Miller GH, Marquez-Velarde G, Mills AR, et al. Patients’ perceived level of clinician knowledge of transgender health care, self-rated health, and psychological distress among transgender adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2315083.

149. Worly B, Manriquez M, Stagg A, et al. Sexual health education in obstetrics and gynecology (Ob-Gyn) residencies-a resident physician survey. J Sex Med. 2021;18:1042-52.

150. Whitney N, Samuel A, Douglass L, Strand NK, Hamidian Jahromi A. Avoiding assumptions: sexual function in transgender and non-binary individuals. J Sex Med. 2022;19:1032-4.

151. Thurston MD, Allan S. Sexuality and sexual experiences during gender transition: A thematic synthesis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;66:39-50.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Issue

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].