Surgical and functional outcomes of penoscrotal vaginoplasty in AMAB transgender patients: a comprehensive analysis of patient satisfaction and postoperative findings

Abstract

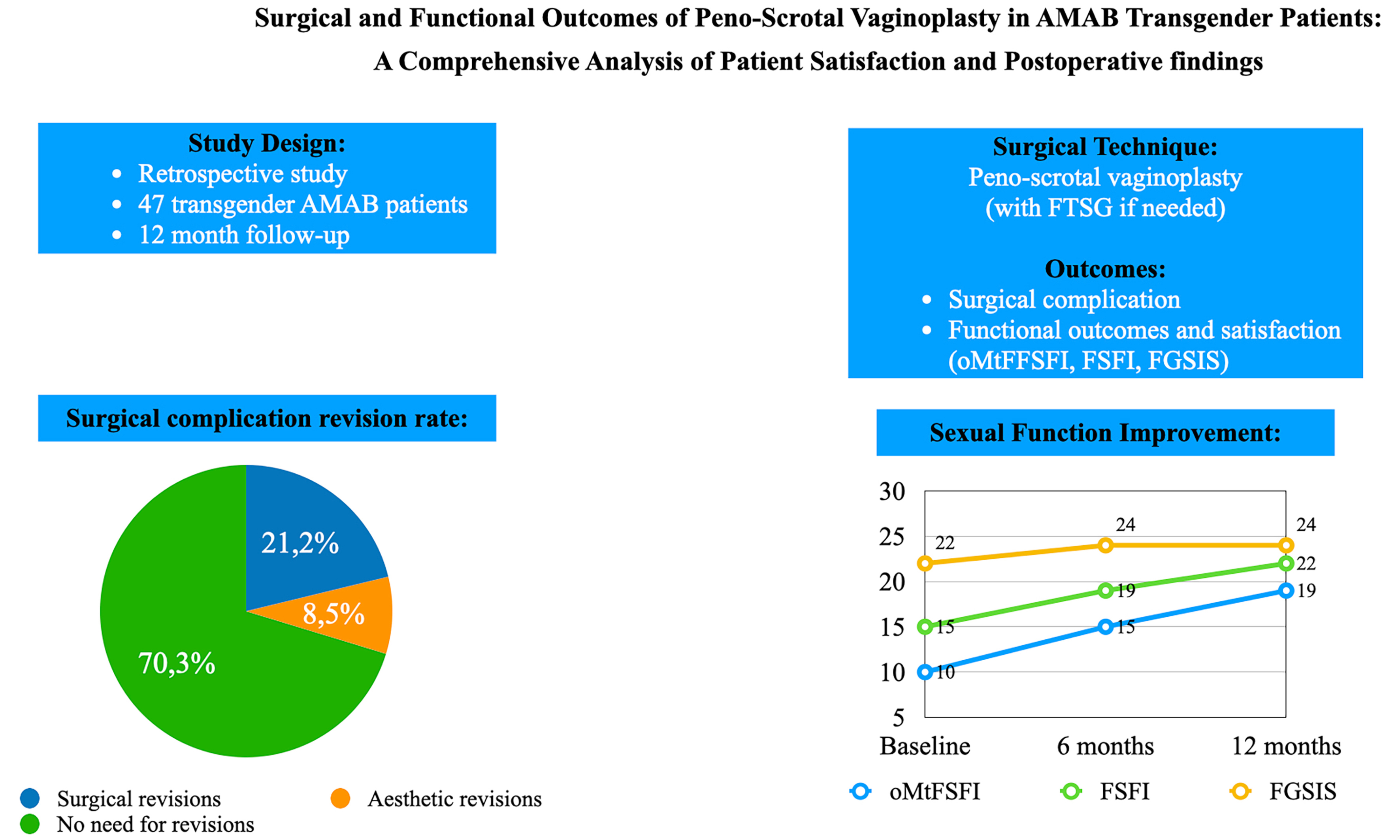

Aim: To evaluate surgical and functional outcomes of assigned male at birth (AMAB) transgender patients who received penoscrotal vaginoplasty at an Italian referral center.

Methods: A retrospective analysis included AMAB transgender patients who received penoscrotal vaginoplasty between April 2018 and April 2024. Patient demographic data, surgical outcomes, complications, and functional outcomes were collected and analyzed. Functional outcomes were assessed using validated questionnaires, including the Operated Male-to-Female Sexual Function Index (oMtFSFI), the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), and the Female Genital Self-Image Scale (FGSIS). A follow-up period of 12 months was used, with statistical analyses to identify predictors of complications and patient dissatisfaction.

Results: The study included 47 AMAB transgender patients, with 30 providing complete functional outcome data. Surgical outcomes showed that the median operative time was 315 min, with a median neovaginal depth of 14 cm. Major complications occurred in 21.2%, including meatal stenosis and one case of rectovaginal fistula. Functional outcomes showed significant improvement, with 63.3% of patients achieving normal oMtFSFI scores at 12 months. FSFI scores also improved across all domains, and genital self-image progressively improved over time.

Conclusion: Penoscrotal vaginoplasty demonstrates favorable surgical and functional outcomes in AMAB transgender patients, with high levels of patient satisfaction. Despite the complexity and potential for complications, penoscrotal vaginoplasty represents an effective surgical option for aligning physical appearance with gender identity, with progressive improvements in sexual function and genital self-image observed over the first postoperative year.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Gender dysphoria (GD) refers to the discomfort or distress experienced by individuals whose gender identity differs from their assigned sex at birth[1]. This condition can cause significant psychological suffering. The true prevalence of GD remains uncertain, mainly due to variation in study methodologies and diagnostic definitions[1,2]. Only a minority of individuals with GD seek professional care - one Dutch study estimated that about 10% pursue medical support, with even fewer reaching specialized centers[3]. Once diagnosed, transgender women (assigned male at birth, AMAB) typically begin a multidisciplinary psycho-endocrinological pathway to align physical traits with gender identity, which may include psychological support, hormone therapy, and gender-affirming surgery (GAS), such as breast augmentation or genital reconstruction[4].

The gold standard for GAS in AMAB individuals is vaginoplasty, a procedure designed to create a neovagina that closely resembles a natal vagina in both appearance and function, using the existing urogenital tissue[5,6]. Over time, numerous surgical techniques have been developed to improve both aesthetic and functional outcomes while minimizing complication rates. Generally, GAS has shown high patient satisfaction and improved quality of life. Vaginoplasty, which typically involves the inversion of penile skin, remains the gold standard procedure[7-11].

Although vaginoplasty has been carried out for many years, there are relatively few studies that rigorously evaluate its aesthetic, functional, and long-term outcomes, particularly regarding patient satisfaction[12,13].

This study aims to assess the surgical and functional outcomes of transgender women who received vaginoplasty at an Italian referral center.

METHODS

Study setting and patients

A retrospective analysis was conducted at a single center between April 2018 and April 2024, following approval from the local Intercompany Ethics Committee of AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino (Pratica n. 506/2023). The study included all transgender women who underwent penoscrotal vaginoplasty. The patients enrolled in this study had all obtained court authorization to undergo GAS surgery based on their completed psycho-endocrinological assessment. All patients and procedures included in the study were ruled by the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration and the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) guidelines. All subjects provided written informed consent to participate in the study and for the publication of anonymized data.

The primary objectives of the study were to analyze and report surgical and functional outcomes following GAS. Demographic characteristics, surgical outcomes, and intra- and postoperative complications were collected from clinical patient records and operative notes. Postoperative complications were evaluated and classified for severity according to the Clavien-Dindo classification (within 90 days after surgery)[14]. Surgical revision rate within 12 months following the primary surgical procedure was also evaluated.

Functional outcomes as perceived by the transgender women were assessed through the administration of validated questionnaires.

Operated Male-to-Female Sexual Function Index (oMtFSFI) consists of 18 questions: 4 assess genital self-perception, 10 assess sexual satisfaction, and 4 assess vaginal pain. The overall oMtFSFI score is categorized as follows: normal 18-36; mild-moderate 37-49; borderline 50-55; critical > 55[15].

Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI - not specifically intended for transgender women) consists of 19 questions assessing six domains: sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction with intimacy, and dyspareunia. Each domain is scored from 0 to 6 after applying domain-specific correction factors, with higher scores indicating better sexual function. The final FSFI score is obtained by summing the six domain scores, with a maximum total of 36. In cisgender women, a score below 26.55 is considered indicative of sexual dysfunction [Table 1][16,17].

Female sexual function index - FSFI - score interpretation

| Domain | Questions | Score range | Factor | Minimum score | Maximum score |

| Desire | 1, 2 | 1-5 | 0,6 | 1.2 | 6.0 |

| Arousal | 3, 4, 5, 6 | 0-5 | 0,3 | 0 | 6.0 |

| Lubrication | 7, 8, 9, 10 | 0-5 | 0,3 | 0 | 6.0 |

| Orgasm | 11, 12, 13 | 0-5 | 0,4 | 0 | 6.0 |

| Satisfaction | 14, 15, 16 | 0 (or 1)-5 | 0,4 | 0.8 | 6.0 |

| Pain | 17, 18, 19 | 0-5 | 0,4 | 0 | 6.0 |

| Full scale score range | 2.0 | 36.0 | |||

Female Genital Self-Image Scale (FGSIS - not specifically intended for transgender women) is composed of seven items that evaluate women’s feelings and beliefs about their genitalia using a 4-point response scale (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree). The scores for each item were summed for a total score ranging from 7 to 28, with higher scores indicating a more positive genital self-image[18].

The questionnaires were administered to every patient via email or during a follow-up consultation in a clinical setting at 3, 6, and 12 months after GAS.

Patients with incomplete data or follow-up were excluded from the study.

Surgical technique

All patients received penoscrotal vaginoplasty carried out by two consultant urologists with specific training in andrology surgery and genital reconstructive surgery.

All patients received standard antibiotic prophylaxis with 2 g of intravenous cefazolin at induction, followed by a repeat dose after 4 h of surgery. At that time, a single dose of intravenous amikacin (1 g) was also administered. Thromboembolic prophylaxis was performed using low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), typically initiated on postoperative day 2 or 3, depending on individual bleeding risk. This approach reflects the generally low thromboembolic risk profile of our patient population, who were predominantly young and otherwise healthy.

The vaginoplasty included penectomy, bilateral orchiectomy, vulvoplasty, and creation of the vaginal canal, aiming to achieve an aesthetically pleasing and functional genital complex. The surgical procedure was carried out under general anesthesia with the patient in the lithotomy position, with legs placed on calf stirrups to provide adequate exposure of the perineum and external genitalia.

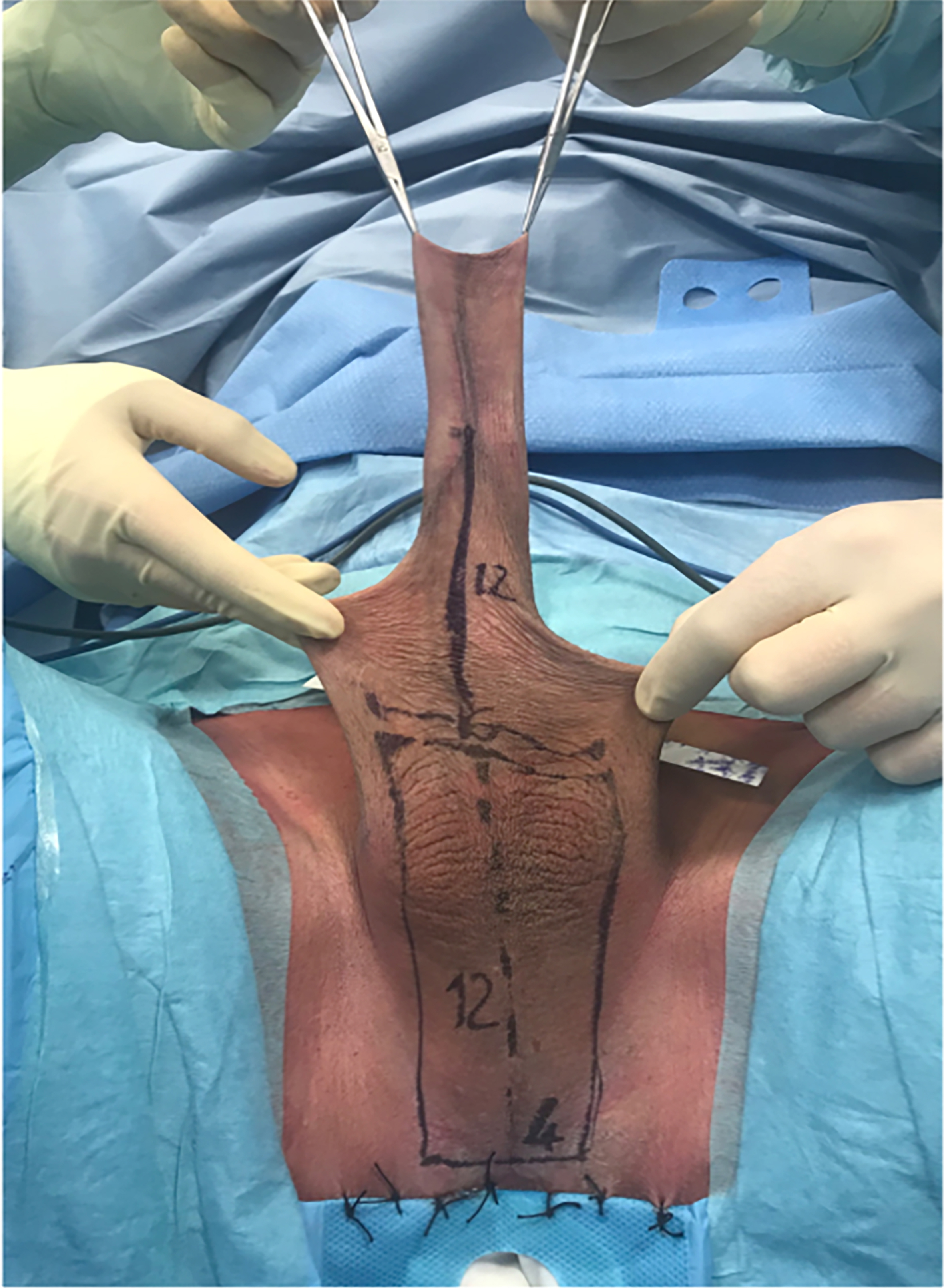

The first phase of the procedure was the demolitive phase, involving bilateral orchiectomy and penectomy. During this phase, tissues and anatomical structures necessary for the subsequent reconstructive phase were preserved. A perineoscrotal skin flap was elevated, and the penile shaft skin was preserved. [Figure 1].

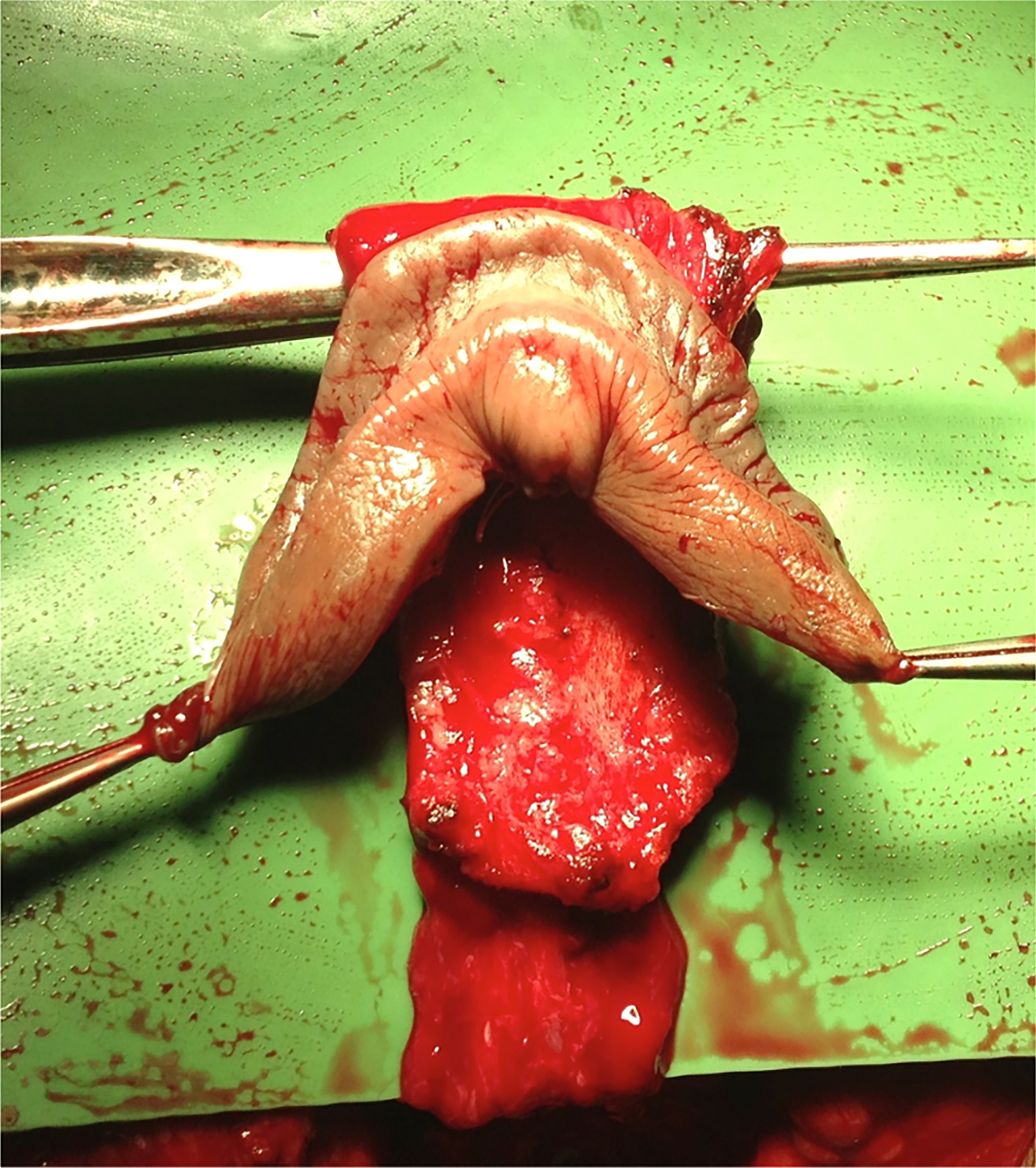

A urethral mucosal flap was also preserved to create the neovulvar vestibule, along with retraction of the urethral meatus and meatoplasty. The preputial skin flap (if available), the neurovascular bundle attached to the dorsal portion of the tunica albuginea, and the dorsocentral portion of the glans (reconfigured according to Preecha’s technique) were preserved for the construction of the clitoral complex, clitoral hood, and labia minora. [Figure 2].

Once the neovaginal cavity was created (between the rectal wall and the urethroprostatic plane, following Denonvilliers’ fascia), it was lined with appropriately approximated and sutured perineoscrotal and penile skin flaps. In cases of limited skin availability, a full-thickness skin graft harvested from excess scrotal skin was applied to ensure maximum neovaginal depth. After lining the vaginal cavity, the neovulvar vestibule (including the clitoral complex/labia minora, urethral meatus, and vaginal introitus) was completed, and the labia majora were created and sutured. (Figure 3 - for more details about the surgical technique, see Supplementary Figures 1-3)

Postoperative management

At the end of the surgical procedure, a vaginal dilator was placed inside the neovaginal cavity, and a compressive dressing applied for five days. On postoperative day 5, the compressive dressing, vaginal stent, and catheter were removed. Initially, a soft dilator was used at night for the first 15 days, followed by rigid dilators, with three one-hour dilation sessions per day, for at least nine months. The first postoperative visit was scheduled around 21 days after the procedure. The follow-up visits were scheduled at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery to evaluate the healing process, the findings of the dilation regimen, and to rule out complications or the need for surgical revision. Sexual activity was allowed starting from the second month post-surgery.

Statistical analysis

The normality of variable distributions was tested by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. For continuous variables with a normal distribution, mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported, whereas variables with a non-normal distribution were described using median and interquartile range (IQR). Differences between groups were assessed by the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for discrete variables. For continuous variables, differences between groups were assessed by the Student’s t-test for normally distributed and the Mann-Whitney U test or the Wilcoxon test (respectively for independent and paired samples) for non-normally distributed variables. A multivariate analysis through logistic binary regression and linear regression was conducted to identify predictors of complications and dissatisfaction. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; v. 29; IBM, Chicago, USA).

RESULTS

Population characteristics

The study population included a total of 47 transgender AMAB patients who received penoscrotal vaginoplasty at our center between April 2018 and April 2024. All of the patients who received surgery were contacted and invited to participate in the study, and all consented. Complete functional outcomes, assessed through the validated questionnaires, were available for 30 out of 47 patients.

Table 2 summarizes the baseline and perioperative characteristics of the study population. The median age at the time of surgery was 31 years (IQR 26-36), and the median BMI was 22 kg/m2 (IQR 21-24). Fourteen patients (30%) were active smokers at the time of surgery. The mean follow-up duration was 35 months (IQR 18-62).

Patients’ characteristics

| Variables | Results |

| Patients, n | 47 |

| Age, (years), median (IQR) | 31 (26-36) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 22 (21-24) |

| Smoke, n (%) | 14 (30) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 2 (4.2) 1 Coagulopathy (2.1) 1 Previous cerebral thrombosis (2.1) |

| Follow-up (months), median (IQR) | 35 (18-62) |

Surgical outcomes

Table 3 details surgical characteristics and complications. The median operative time was 315 min (IQR 287-342). Median neovaginal depth at the end of the procedure was 14 cm (IQR 12-14). In 9 cases out of 47 (19.1%), the available genital skin was insufficient to fully line the newly created vaginal cavity, necessitating the use of a full-thickness skin graft to augment the neovaginal lining. The median intraoperative blood loss was 500 mL (IQR 300-650). The median hospital stay was 8 days (IQR 7-9). One intraoperative complication (2.1%) was recorded: a bulbar urethral injury sustained during neovaginal space dissection. This was successfully repaired intraoperatively, using a multilayered suture technique with absorbable material to reconstruct the urethral mucosa and spongiosa. The patient experienced full recovery following prolonged catheterization (2 weeks). In this unique case, a retrograde and voiding cystourethrography was also performed to confirm complete healing.

Surgical characteristics and complications

| Variables | Results |

| Operative time, median (IQR) | 315 (287-342) |

| Final length, cm (IQR) | 14 (12-14) |

| Blood loss, mL (IQR) | 500 (300-650) |

| Graft, n (%) | 9 (19.1) |

| Hospital stay (days), median (IQR) | 8 (7-9) |

| Intraoperative complication, n (%) | 1 (2.1) Bulbar urethra injury |

| Postoperative complication, n (%) | 30 (63.8) |

| Clavien-Dindo I - Anemization - Wound dehiscence/infection | 8 (17) 5 (10.6) 3 (6.4) |

| Clavien-Dindo II - Blood transfusion | 12 (25.5) 12 (25.5) |

| Clavien-Dindo III (surgical revision rate) - Meatal stenosis - Neovaginal stenosis - Rectovaginal fistula | 9 (19.1) 7 (14.9) 1 (2.1) 1 (2.1) |

| Clavien-Dindo IV - Hemorrhagic shock | 1 (2.1) 1 (2.1) |

Considering postoperative complications, minor complications (Clavien-Dindo I-II) were reported in 42.5% of cases (22 patients). The majority of these complications were related to postoperative anemia, affecting 17 patients, 12 (25.5%) of whom required blood transfusion support. Additionally, 3 patients (6.4%) experienced wound healing complications, necessitating advanced wound care management in an outpatient setting.

In addition to minor complications, major complications (Clavien-Dindo III-IV) were observed in 21.2% of cases. The majority were grade III complications, primarily meatal stenosis, affecting 7 patients (14.9%), all of whom required surgical correction via ventral meatoplasty performed in a day surgery setting. One patient (2.4%) developed a rectovaginal fistula requiring a temporary colostomy, which ultimately led to permanent functional impairment due to neovaginal stenosis. Moreover, esthetic revision surgery was performed in 4 out of 47 patients (8.5%), primarily for minor corrections such as asymmetries or irregularities of the external genitalia. However, detailed classification of these revision requests was not recorded in the retrospective data collection.

Neovaginal depth reduction was observed in 4 patients (9.8%) after a median elapsed time of 12 months post-surgery. Of these, three cases (7.3%) were managed conservatively with self-dilation, as they did not require surgical intervention or compromise neovaginal function (1-year vaginal depth 10 cm), while one case (2.1%) necessitated revision surgery to release adhesions and restore depth (pre-revision depth was 8.5 cm). At 1-year follow-up, the median neovaginal depth across the cohort was 12.5 cm (IQR: 10.5-13.0 cm).

Additionally, significant neovaginal bleeding occurred in one patient (2.1%), leading to hemorrhagic shock and requiring hospitalization and blood transfusions (Clavien IV).

In the multivariate analysis of postoperative complications, none of the analyzed predictors were found to be statistically significantly correlated. [Table 4].

Multivariate analysis - predictors of complications

| Postoperative complications | ||||||

| Coefficient | Standard error | P value | Odds ratio | 95%CI for odds ratio | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age | 0.019 | 0.042 | 0.645 | 1.019 | 0.939 | 1.106 |

| BMI | 0.020 | 0.107 | 0.855 | 1.020 | 0.827 | 1.257 |

| Neovaginal length | -0.272 | 0.352 | 0.440 | 0.762 | 0.382 | 1.519 |

| Age > 35 | 0.506 | 0.967 | 0.601 | 1.658 | 0.249 | 11.038 |

| BMI > 24 | 0.123 | 0.765 | 0.872 | 1.131 | 0.253 | 5.062 |

| Smoke | 0.344 | 0.540 | 0.524 | 1.411 | 0.490 | 4.067 |

| Graft | 0.405 | 0.833 | 0.627 | 1.500 | 0.293 | 7.681 |

Functional outcomes

Of the 47 eligible patients, 30 completed and returned the functional outcome questionnaires during the follow-up period, and the overall response rate was 63.8%. The remaining patients were excluded from the functional outcomes analysis. All functional data related to questionnaires were reported in Table 5.

Functional outcomes

| Operated male-to-female sexual function index - oMtFSFI | |||||

| Range | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | ||

| Normal %, n | 10/30 (33.3%) | 15/30 (50%)* | 19/30 (63.3%)*° | ||

| Mild-moderate %, n | 9/30 (30.0%) | 9/30 (30.0%) | 11/30 (36.7%) | ||

| Borderline %, n | 4/30 (13.3%) | 3/30 (6.7%) | 0/30 (0.0%) | ||

| Critical %, n | 7/30 (23.4%) | 4/30 (13.3%) | 0/30 (0.0%) | ||

| Female sexual function index - FSFI scores | |||||

| Domains | Questions | Score range | 3 months median (IQR) | 6 months median (IQR) | 12 months median (IQR) |

| Desire | 1, 2 | 1-5 | 2.4 (1.5-3) | 3 (2.4-3.6) | 3 (2.2-3.6) |

| Arousal | 3, 4, 5, 6 | 0-5 | 2.4 (1.8-3.6) | 3.6 (2.7-3.8) | 4 (3.6-4.8) |

| Lubrication | 7, 8, 9, 10 | 0-5 | 1.8 (1.5-3.6) | 3 (2.2-4.2) | 4.2 (3.6-4.5) |

| Orgasm | 11, 12, 13 | 0-5 | 2.2 (1.6-3.6) | 2.4 (2-2.8) | 4 (3.6-4.4) |

| Satisfaction | 14, 15, 16 | 0-5 | 3.8 (2.8-4.4) | 3.6 (2.8-4.4) | 4.4 (3.4-4.8) |

| Pain | 17, 18, 19 | 0 - 5 | 3 (2-4.4) | 3.6 (3-4) | 4 (3.4-4.4) |

| Total | 36 | 14.9 (13-19.8) | 18.6 (16.8-22) | 22.2 (20-25.7) | |

| Female genital self-image scale - FGSIS scores | |||||

| 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |||

| Median (IQR) | 22 (20-24.5) | 24 (20.75-24.75) | 24 (21-26) | ||

oMtFSFI

Sexual function was assessed using the oMtFSFI questionnaire at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. The proportion of patients achieving a normal score increased progressively, from 33.3% at 3 months to 50% at 6 months, reaching 63.3% at 12 months.

Conversely, the percentage of patients with critical scores showed a marked reduction from 23.4% at 3 months to 13.3% at 6 months, with no cases reported at 12 months. Similarly, borderline scores were recorded in 13.3% of patients at 3 months and 6.7% at 6 months, but no patients remained in this category by 12 months.

The proportion of patients with mild-to-moderate scores remained relatively stable over time, reported at 30% at 3 months, 30% at 6 months, and 36.7% at 12 months. [Table 5].

A multivariate analysis was conducted to identify potential predictors of satisfaction, defined as achieving a normal oMtFSFI score at 12 months. However, no significant risk factors for lower satisfaction rates were identified. [Table 6].

Multivariate analysis for potential predictors of satisfaction

| oMtFSFI 6 months | ||||||

| Coefficient | Standard error | P value | Odds ratio | 95%CI for odds ratio | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age | 0.115 | 0.099 | 0.245 | 1.122 | 0.924 | 1.363 |

| BMI | -0.557 | 0.343 | 0.104 | 0.573 | 0.292 | 1.122 |

| Neovaginal length | 1.776 | 1.552 | 0.253 | 5.908 | 0.282 | 123.798 |

| Clavien-Dindo | 2.752 | 1.511 | 0.069 | 15.678 | 0.811 | 302.979 |

| Age > 35 | 4.574 | 2.485 | 0.066 | 96.912 | 0.744 | 12631.3 |

| BMI > 24 | -3.934 | 2.518 | 0.118 | 0.020 | 0.000 | 2.724 |

| Smoke | -2.771 | 1.508 | 0.066 | 0.063 | 0.003 | 1.204 |

| Postoperative complications | 2.522 | 1.498 | 0.092 | 12.459 | 0.661 | 234.687 |

| Graft | 0.194 | 0.976 | 0.842 | 1.214 | 0.179 | 8.217 |

FSFI

Sexual function was further assessed using the FSFI questionnaire at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. The results demonstrated a progressive improvement across all domains over time. Sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasmic function, satisfaction with intimacy, and pain scores all showed a consistent upward trend, indicating enhanced sexual well-being as the recovery process advanced. Notably, the total FSFI score increased significantly from 14.9 (IQR 13-19.8) at 3 months to 18.6 (IQR 16.8-22) at 6 months, reaching 22.2 (IQR 20-25.7) at 12 months post-surgery. The detailed scores for each domain are reported in Table 5.

FGSIS

Genital self-image was assessed using the FGSIS questionnaire at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. The results showed a progressive improvement in patients’ perception of their external genitalia over time. The median score increased from 22 (IQR 20-24.5) at 3 months to 24 (IQR 20.75-24.75) at 6 months, remaining stable at 24 (IQR 22-25) at 12 months. [Table 5].

DISCUSSION

Genital GAS is a key step in the transition process for many AMAB individuals[4,19]. It has been associated with reduced GD, greater body satisfaction, improved social integration, and enhanced quality of life[10,20-23]. However, current evidence is limited by small sample sizes, retrospective designs, heterogeneous outcomes, and inconsistent terminology[24-26]. These issues hinder comparisons between techniques and the development of standardized guidelines. Moreover, most studies rely on tools designed for cisgender populations, which may not adequately reflect the experiences of transgender individuals.

Our study aimed to provide an objective and reproducible evaluation of both surgical and functional outcomes following penoscrotal vaginoplasty using validated tools during the follow-up. Regarding surgical outcomes, our combined penoscrotal flap technique, with the optional use of a full-thickness skin graft in cases of limited tissue availability, achieved a median neovaginal depth of 14 cm (IQR 12-14).

This finding is in complete agreement with the existing literature, where the mean neovaginal depth has been reported to range from 10 to 13.5 cm[27,28].

Similarly, in the series by Buncamper et al, no significant differences were observed in postoperative depth between patients who underwent vaginoplasty with or without a skin graft. In both groups, the median recorded depth was 13.8 cm. Furthermore, during follow-up, the authors reported a comparable degree of neovaginal cavity reduction after at least one year, estimated at approximately 2.1-2.5 cm[6].

Supporting the significance of achieving sufficient depth for postoperative satisfaction, Karim et al. postulated that a neovaginal depth of at least 10 cm is necessary for functional penetrative sexual intercourse[5].

Regarding surgical complications, previous literature reports variable rates ranging from 33% to 47%[29]. The majority of these are classified as minor and do not require surgical revision. Rectovaginal fistula rates are reported to be around 1%-2%[12,27-29], while urethral complications occur in approximately 1%-6% of cases[12,27,30-32]. Neovaginal stenosis has been documented in 2%-10% of patients undergoing surgery[2,12,27,31,33].

In our series, the incidence of major complications was comparable to previously published studies. Notably, we observed a higher rate of meatal stenosis (~15%), which was more frequent during the earlier phase of our surgical experience. This suggests that improvements in ureteral stump management and neomeatus configuration over time - reflecting the surgical learning curve - contributed to reduced complications in later cases. Similarly, the retrospective study by Raigosa et al. reported a 15% complication rate in 60 patients undergoing vaginoplasty with penile and scrotal skin flaps, with most issues related to the urethra or introitus[34]. This is consistent with our findings and reinforces the viability of the penoscrotal approach when performed in experienced centers.

Surgical revision for urethral complications in some series can reach up to 20%[29]. Our data align with previously published data. However, the majority of revision procedures (approximately 43%) were performed for aesthetic reasons. In our current series, aesthetic revision requests were not detailed, but they only involved 4 patients out of 47 (8.5%). Recent prospective data from Mañero et al. highlight the importance of systematically evaluating not only surgical outcomes, but also functional, aesthetic, and sensory complications following transfeminine vaginoplasty. In their 2022 study, over 60% of patients experienced at least one postoperative issue, including sexual dysfunction and altered genital sensitivity, despite high overall satisfaction rates[35]. In our cohort, a proportion of patients reported some degree of sexual dysfunction at 12 months, most commonly related to reduced genital sensitivity or mild discomfort during penetration. While these findings underscore the need for long-term follow-up and targeted postoperative counseling, it is important to interpret them within a broader context. Although these scores were actually higher than those reported in a sample of Italian cisgender female undergraduates in a 2018 study[36], it should be noted that comparisons across populations must be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, Mañero et al., in another manuscript, emphasized the demand for aesthetic revision surgery in transfeminine patients, reporting a revision rate of 22.9%, primarily for labia minora asymmetry, clitoral hood irregularities, and introitus contour[37]. Differences in patient expectations, surgical technique, follow-up duration, and even legal or cultural factors may help explain this discrepancy.

The overall revision rate in our series, combining both aesthetic and complication-related revisions, was 27.6%, which is similar to previously published global revision rates around 27%[2].

Finally, a notable difference from other series is the absence of neovaginal prolapse in our cohort. While previous studies have reported this complication in approximately 2% of cases[12,38,39], those data primarily derive from penile inversion techniques rather than penoscrotal flaps. Additionally, unlike historical approaches, modern penoscrotal flap techniques no longer involve fixation to the prostatic capsule, which was a common practice in the past.

Regarding the response rate to functional questionnaires during follow-up, we achieved a response rate of 63.8%. Similar studies addressing functional outcomes reported comparable response rates, which highlights the challenges of following these patients over time and obtaining large sample sizes. This difficulty arises because patients are often unreachable or non-compliant in completing the questionnaires during the long-term postoperative period. Monstrey et al. reported similar challenges in contacting women after surgery, as they could not be located[40]. Reasons for not wanting to participate included “research fatigue” or “to be done with being seen as a patient” and desire to move beyond the surgical aspect and return to everyday life. However, it is possible that this has introduced a bias in the results[29].

As supported by other series, the overall results from the different questionnaires confirm that GAS leads to high success rates, patient satisfaction, and an overall improvement in quality of life[10,41,42].

Specifically, the oMtFSFI questionnaire, which was designed to assess sexual function in transgender women, offers a more tailored evaluation of postoperative outcomes compared to generic tools designed for cisgender populations. The progressive improvement in oMtFSFI scores observed over time suggests a clear trend toward functional recovery and enhanced sexual well-being following vaginoplasty.

At 3 months, only 33.3% of patients achieved scores classified as normal, while a considerable proportion still fell into the mild-to-moderate, borderline, or even critical ranges. This likely reflects the early postoperative challenges, including ongoing healing, tissue adaptation, and psychological adjustments. However, by 6 months, the percentage of patients in the normal range increased to 50%, with a corresponding decline in those reporting critical dysfunction. At 12 months, the trend was even more pronounced, with 63.3% of patients reaching normal function and no cases in the borderline or critical categories.

The steady increase in normal scores, coupled with the significant reduction in severe dysfunction, suggests that sexual function continues to improve well beyond the immediate postoperative period. These findings highlight the importance of long-term follow-up and postoperative support, as patients may require time to adapt physically and psychologically to their new anatomy. The persistence of mild-to-moderate dysfunction in a subset of patients (36.7% at 12 months) indicates that, while most individuals achieve satisfactory outcomes, some may require additional interventions to optimize function Additionally, while the oMtFSFI provides a more appropriate assessment tool for transgender women, further research is needed to refine its scoring thresholds and ensure that it accurately captures the nuances of sexual health in this population. Indeed, functional outcomes using this specific validated tool are not frequently reported in the literature.

It is debatable whether a questionnaire designed for cisgender women can reliably assess female genital self-image or sexual function in the AMAB transgender population. In our study, we used two additional questionnaires to better investigate sexual function and genital self-image in our patients, as no other tools specifically designed for AMAB patients are currently available.

Regarding the FSFI questionnaire, there are inherent limitations when applied to transgender women, particularly concerning the established cutoff for sexual dysfunction (score of 26.55). Given the anatomical and physiological differences in neovaginal function, as well as potential disparities in sensory perception and lubrication, the direct application of this threshold to our cohort may not be entirely appropriate. In our cohort, 22 patients (73.3%) reported being sexually active at 12 months. Among them, the median FSFI score at 12 months postoperatively was 24.8 (IQR: 22.2-27.1), slightly higher than the overall cohort median score of 22.2 (IQR 20-25.7). Comparable outcomes are reported in the literature (e.g., FSFI score of 16.9 and 23.7 in the series by Buncamper et al. and 26.67 in the series by Monteiro et al.[2,6,29]). This supports the notion that sexual activity is associated with better FSFI scores and may help explain differences across studies.

Additionally, no significant differences in FSFI scores were observed between patients who underwent vaginal cavity expansion using a skin graft. Furthermore, the FSFI score appeared only marginally related to the functionality of the neovagina and was not correlated with the grade given for overall satisfaction (P = 0.13)[6].

These low scores may be explained by the fact that the FSFI is not specifically designed for transgender patients and does not adequately assess the unique aspects of sexual functionality in individuals with reconstructed genitalia. It is worth noting that the domain of the questionnaire assessing satisfaction consistently had the highest scores at all follow-up time points (at 3, 6, and 12 months). Similarly, in the literature, the most difficult domain in the FSFI appears to be lubrication. Since the neovagina does not contain mucous tissue and, therefore, cannot produce fluids, lubrication issues are an expected limitation of this surgery[6,29]. Despite this limitation, the progressive improvement observed across all FSFI domains over time suggests a significant enhancement in sexual function postoperatively, potentially nearing normative values established for cisgender women, indicating substantial recovery and adaptation. Indeed,

Regarding the questionnaire assessing genital self-image (FGSIS), the score at 12 months in our population was 24 (range: 21-26), comparable to other series, such as 22.6 in the series by Buncamper et al. and 21.8 in another series by the same group[6,29]. Furthermore, we found an interesting comparison with the scores of cisgender women in a representative sample of the U.S. population (21.3)[18]. The results obtained from the FGSIS suggest that the participants were generally positive about their genital self-image. Unfortunately, no data are available for such a comparison in the Italian population.

The progressive improvement in FGSIS scores over time suggests that as the postoperative period advances, patients tend to develop a more positive perception of their neogenitalia, reflecting increasing satisfaction and adaptation to their surgical outcomes. This trend aligns with previous findings in GAS, where initial concerns about appearance and functionality tend to decrease as patients become more accustomed to their bodies and experience improved quality of life. In this context, recent survey data[43] demonstrated that transgender women who had undergone vaginoplasty reported significantly higher FGSIS scores compared with those awaiting surgery (79.4% ± 17.1% vs. 50.6% ± 15.1%, P < 0.0001). Interestingly, in the postoperative cohort, no correlation was found between FGSIS scores and sexual health outcomes, suggesting that genital self-image and sexual function may evolve independently. This supports the notion that sexual health in transgender women is a multifactorial construct, requiring multidimensional and population-specific assessment tools[43].

Considering the positive findings observed at least 12 months after surgery, multivariate analyses were carried out to identify factors potentially associated with overall patient satisfaction. However, no clear preoperative or intraoperative predictors of adverse satisfaction outcomes emerged in our cohort. Interestingly, although not statistically significant, a trend was observed toward better sexual function (oMtFSFI scores) in patients who were active smokers and lower satisfaction in patients over 35 years old. These findings may reflect unmeasured psychosocial or behavioral factors not captured in our dataset, and highlight the importance of integrating broader health and lifestyle variables in future prospective studies. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to better define risk factors and optimize patient selection and perioperative management.

Furthermore, these data reinforce the importance of long-term follow-up in assessing functional outcomes beyond the early postoperative phase and underline the value of patient education in GAS. A multidisciplinary approach remains essential to ensure both surgical success and long-term functional well-being. Moreover, there is a pressing need for transgender-specific tools to evaluate sexual function and patient satisfaction, given the limitations of instruments designed for cisgender populations, to better capture the unique aspects of neovaginal physiology and patient-reported satisfaction.

A primary limitation of this study, shared with other reports on similar populations, is the low post-surgical adherence to research protocols, resulting in small sample sizes and underpowered analyses[44,45]. Additional limitations include the retrospective, single-center design, short follow-up, and patient attrition. The lack of standardized protocols for assessing complications and outcomes further limits the generalizability of findings. Identifying the most effective vaginoplasty technique for AMAB patients remains challenging because of heterogeneity in surgical approaches, patient populations, and outcome measures. Future prospective, multicenter studies with standardized surgical techniques, longer follow-up, and validated instruments - such as the recently developed GENDER-Q[46], specifically designed to assess patient-reported outcomes in GAS - are essential to improve comparability and data reliability. Notably, the GENDER-Q was not employed in our cohort because of its recent introduction and unavailability at the time of data collection.

Penoscrotal vaginoplasty represents an effective and reliable surgical option in GAS for AMAB patients, offering favorable outcomes and high satisfaction rates. Beyond the technical success, this study provides valuable longitudinal data showing progressive improvements in sexual function and genital self-image over the first postoperative year. These findings emphasize the importance of long-term follow-up and set realistic expectations for patients, who should be counseled that optimal functional outcomes may take several months to achieve. This gradual recovery process underlines the need for structured postoperative support and reinforces the value of specialized, multidisciplinary care.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and/or designed the work that led to the submission, acquired data, and/or played an important role in interpreting the findings: Falcone M, Preto M, Ferro I, Cirigliano L, Guadagni L, Plamadeala N, Scavone M

Drafted or revised the manuscript: Plamadeala N, Preto M, Ferro I, Cirigliano L, Guadagni L, Zupo E

Approved the final version: Falcone M, Preto M, Timpano M, Gontero P

Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: Falcone M, Preto M, Timpano M, Gontero P

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting this study are securely stored in a hospital database and are protected for confidentiality reasons. Access to the dataset is available upon reasonable request to the first author, in accordance with institutional and ethical guidelines.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Preto M is a Junior Editorial Board member of the journal Plastic and Aesthetic Research. Preto M was not involved in any steps of editorial processing, notably including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision making. The other authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Intercompany Ethics Committee of AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino (Comitato Etico Interaziendale AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino), Pratica n. 506/2023. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study and for the publication of anonymized data.

Consent for publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA; 2013.

2. Monteiro Petry Jardim LM, Cerentini TM, et al. Sexual function and quality of life in braziliantransgenderwomen followinggender-affirming surgery: across-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:15773.

3. Kuyper L, Wijsen C. Gender identities and gender dysphoria in the Netherlands. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43:377-85.

4. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23:S1-259.

5. Karim RB, Hage JJ, Bouman FG, de Ruyter R, van Kesteren PJ. Refinements of pre-, intra-, and postoperative care to prevent complications of vaginoplasty in male transsexuals. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;35:279-84.

6. Buncamper ME, van der Sluis WB, de Vries M, Witte BI, Bouman MB, Mullender MG. Penile inversion vaginoplasty with or without additional full-thickness skin graft: to graft or not to graft? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:649e-56.

7. Small MP. Penile and scrotal inversion vaginoplasty for male to female transsexuals. Urology. 1987;29:593-7.

9. Oles N, Darrach H, Landford W, et al. Gender affirming surgery: a comprehensive, systematic review of all peer-reviewed literature and methods of assessing patient-centered outcomes (Part 2: genital reconstruction). Ann Surg. 2022;275:e67-74.

10. Javier C, Crimston CR, Barlow FK. Surgical satisfaction and quality of life outcomes reported by transgender men and women at least one year post gender-affirming surgery: a systematic literature review. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23:255-73.

11. De Cuypere G, T'Sjoen G, Beerten R, et al. Sexual and physical health after sex reassignment surgery. Arch Sex Behav. 2005;34:679-90.

12. Krege S, Bex A, Lümmen G, Rübben H. Male-to-female transsexualism: a technique, results and long-term follow-up in 66 patients. BJU Int. 2001;88:396-402.

13. Green R. Sexual functioning in post-operative transsexuals: male-to-female and female-to-male. Int J Impot Res. 1998;10 Suppl 1:S22-4.

14. Mitropoulos D, Artibani W, Biyani CS, Bjerggaard Jensen J, Rouprêt M, Truss M. Validation of the clavien-dindo grading system in urology by the European association of urology guidelines ad hoc panel. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;4:608-13.

15. Vedovo F, Di Blas L, Perin C, et al. Operated male-to-female sexual function index: validity of the first questionnaire developed to assess sexual function after male-to-female gender affirming surgery. J Urol. 2020;204:115-20.

16. Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191-208.

17. Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31:1-20.

18. Herbenick D, Reece M. Development and validation of the female genital self-image scale. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1822-30.

19. Djordjevic ML, Salgado CJ, Bizic M, Kuehhas FE. Gender dysphoria: the role of sex reassignment surgery. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:645109.

20. Kuhn A, Bodmer C, Stadlmayr W, Kuhn P, Mueller MD, Birkhäuser M. Quality of life 15 years after sex reassignment surgery for transsexualism. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1685-9.e3.

21. van de Grift TC, Elaut E, Cerwenka SC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Kreukels BPC. Surgical satisfaction, quality of life, and their association after gender-affirming surgery: a follow-up study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2018;44:138-48.

22. Salvador J, Massuda R, Andreazza T, et al. Minimum 2-year follow up of sex reassignment surgery in Brazilian male-to-female transsexuals. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;66:371-2.

23. Cardoso da Silva D, Schwarz K, Fontanari AM, et al. WHOQOL-100 before and after sex reassignment surgery in brazilian male-to-female transsexual individuals. J Sex Med. 2016;13:988-93.

24. Tunis SR, Clarke M, Gorst SL, et al. Improving the relevance and consistency of outcomes in comparative effectiveness research. J Comp Eff Res. 2016;5:193-205.

25. Cocci A, Frediani D, Cacciamani GE, et al. Systematic review of studies reporting perioperative and functional outcomes following male-to-female gender assignment surgery (MtoF GAS): a call for standardization in data reporting. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2019;71:479-86.

26. Dunford C, Bell K, Rashid T. Genital reconstructive surgery in male to female transgender patients: a systematic review of primary surgical techniques, complication profiles, and functional outcomes from 1950 to present day. Eur Urol Focus. 2021;7:464-71.

27. Amend B, Seibold J, Toomey P, Stenzl A, Sievert KD. Surgical reconstruction for male-to-female sex reassignment. Eur Urol. 2013;64:141-9.

28. Horbach SE, Bouman MB, Smit JM, Özer M, Buncamper ME, Mullender MG. Outcome of vaginoplasty in male-to-female transgenders: a systematic review of surgical techniques. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1499-512.

29. Buncamper ME, Honselaar JS, Bouman MB, Özer M, Kreukels BP, Mullender MG. Aesthetic and functional outcomes of neovaginoplasty using penile skin in male-to-female transsexuals. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1626-34.

30. Reed HM. Aesthetic and functional male to female genital and perineal surgery: feminizing vaginoplasty. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25:163-74.

31. Perovic SV, Stanojevic DS, Djordjevic ML. Vaginoplasty in male transsexuals using penile skin and a urethral flap. BJU Int. 2000;86:843-50.

32. Lawrence AA. Patient-reported complications and functional outcomes of male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35:717-27.

33. Wagner S, Greco F, Hoda MR, et al. Male-to-female transsexualism: technique, results and 3-year follow-up in 50 patients. Urol Int. 2010;84:330-3.

34. Raigosa M, Avvedimento S, Yoon TS, Cruz-Gimeno J, Rodriguez G, Fontdevila J. Male-to-female genital reassignment surgery: a retrospective review of surgical technique and complications in 60 patients. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1837-45.

35. Vazquez I, Labanca T, Arno AI. Functional, aesthetic, and sensory postoperative complications of female genital gender affirmation surgery: a prospective study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2022;75:4312-20.

36. Bezerra KC, Feitoza SR, Vasconcelos CTM, Karbage SAL, Saboia DM, Oriá MOB. Sexual function of undergraduate women: a comparative study between Brazil and Italy. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71:1428-34.

37. Mañero I, Arno AI, Herrero R, Labanca T. Cosmetic revision surgeries after transfeminine vaginoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2023;47:430-41.

38. Goddard JC, Vickery RM, Qureshi A, Summerton DJ, Khoosal D, Terry TR. Feminizing genitoplasty in adult transsexuals: early and long-term surgical results. BJU Int. 2007;100:607-13.

39. Tran S, Guillot-Tantay C, Sabbagh P, et al. Systematic review of neovaginal prolapse after vaginoplasty in trans women. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2024;66:101-11.

40. Monstrey S, Hoebeke P, Dhont M, et al. Surgical therapy in transsexual patients: a multi-disciplinary approach. Acta Chir Belg. 2001;101:200-9.

41. Loree JT, Burke MS, Rippe B, Clarke S, Moore SH, Loree TR. Transfeminine gender confirmation surgery with penile inversion vaginoplasty: an initial experience. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8:e2873.

42. Massie JP, Morrison SD, Van Maasdam J, Satterwhite T. Predictors of patient satisfaction and postoperative complications in penile inversion vaginoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:911e-21.

43. Kloer C, Blasdel G, Shakir N, et al. Does genital self-image correspond with sexual health before and after vaginoplasty? Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11:e4806.

44. Lawrence AA. Factors associated with satisfaction or regret following male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32:299-315.

45. Kuhn A, Hiltebrand R, Birkhäuser M. Do transsexuals have micturition disorders? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;131:226-30.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Issue

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].