Exhaustive analysis of scalp hair regression: subjective and objective perception from initial hair loss to severe miniaturisation and drug-induced regrowth

Abstract

Aim: The reason why non-calibrated hair variables poorly estimate scalp hair coverage during hair growth studies was studied.

Methods: Hair productivity integrates density, diameter and daily hair growth rate. Cross-sectional studies have established hair productivity in female and male patients (480 vs. 90 controls) with self-evaluation of hair loss, phototrichogram (CE-PTG-EC) and scalp coverage scoring, (SCS). Tracking productivity of individual hair follicular units from longitudinal studies challenged the application of our methods during drug trials.

Results: Hair loss means decreased productivity and increased “time to complete coverage”. The hair mass index (HMI) linearly connects productivity with clinical perception of coverage, i.e., SCS. The ensuing HMI abacus translates independently of gender, age, pattern or severity and unravelled unequal intervals between categories of the Ludwig and Hamilton classifications. With one severity grade shift, time to complete coverage varied from 21-51 days, i.e., no equality. During longitudinal studies, SCS detected improved productivity, reflecting clinically relevant responses, but remained stable in the absence of significant productivity variations. Follicular unit labelling and individual hair growth tracing showed that reversal of miniaturised hair follicles does not play a major role during drug-induced hair regrowth. The latter reflects re-activation of resting-dormant terminal hair follicles. The recovered productivity would not be possible once hair follicles enter the phase of structural-functional irreversible miniaturisation.

Conclusion: Besides pattern identification, density of nanohair and HMI appear as innovative diagnostic approaches. Abrupt transformation (within one cycle) of terminal hair follicles into miniaturised ones and its reversal as the effect of active FDA-approved drugs remain highly improbable.

Keywords

Introduction

Hair loss may be a distressing phenomenon and the psycho-social burden in terms of self-perception, body image, loss of attractiveness, etc. remains often misunderstood by practitioners. The phenomenon may be overlooked, its potential prevention or improvement with drug treatment ignored and, in the worst case-scenario, the condition is simply denied by professionals[1-3]. During a face-to-face consultation, dermatologists rely on schematic classifications, and even for trained hair specialists an accurate estimation of “pattern and severity” may remain difficult; test-retest experiments of severity scores on images concluded that clinical classification was unreliable[4].

From a more fundamental perspective, cartoons representing patterns raise a number of questions: How do categories reflect the distribution of a continuum? How many patients do not fit the existing classifications? Is rating of severity consistent? Are intervals between grades equal or not in terms of scalp hair regression? In other words, is the difference between severity Grades I and II the same as between Grades II and III, between Grades IV and V, etc.?

Therefore, clinicians have intuitively proposed a wider variety of schemes and extended scales but without supportive evidence that this clinical approach was actually an improvement. In short, the meaning of severity during a clinical diagnostic process in terms of hair productivity is still lacking.

Productivity has to be understood as follows: What amount of hair can be optimally produced by a single organ or a community of organs with the existing resources (nutritional status, genetic-regional variations, hormonal status, etc.)?

From a clinical perspective, we classify patients according to the simplest and most popular schematic representations appearing in textbooks[5]. Firstly, the discrete patterning and severity grades were described by Hamilton[6], who pointed out the essential role of androgens in balding males. Findings that were highlighted by social-historical perspectives[7] soon followed with Ludwig’s classification of patterned loss in females[8]. Secondly, non-invasive methods were employed to record various objective aspects of the scalp hair loss, i.e., global images that correlated with deficient hair replacement and hair follicle miniaturisation[9,10]. Thirdly, recently published therapeutic assays showed that the perception of clinical status could be subject to rapid changes of hair productivity[11-13], albeit without involving a significant fluctuation of miniaturised hair follicles[14]. The latter may also reflect fine tips during the initial steps of a new hair cycle (less than 15 days)[10].

During drug trials, patients have usually not shifted from a more severe to a less severe category or pattern. However, this does not necessarily mean that patients were subjectively satisfied with the therapeutic response[15]. With these discrepancies, the categorical system keeps diagnostic value with little interest for measurement of the therapeutic response.

This paper reports the results of a cross-sectional study with systematic clinical observation, self-evaluation and exhaustive analytical measurements of the scalp hair dynamics on a large number of patients complaining of hair loss. This complex computation resulted in an abacus that helps the observer to translate his clinical quantitative observations into hair productivity, i.e., hair mass index (HMI). While words such as “hair mass” usually refer to a substantial amount of hair without precise measurements, the evidence and rationale for choosing HMI are exposed in Supplement File 1. A short historical note is given as Supplement File 2 explaining the authors’ progression on his way towards accurate and precise hair measurement. With the data from the cross-sectional study at hand, we tested HMI in situations with synchronised short-term changes of hair cycling. Documents from longitudinal placebo-controlled trials (published and unpublished) were re-analysed in terms of global changes and detailed scalp hair productivity.

The present paper proposes innovative non-invasive bio-engineering approaches to document individual hair follicle productivity. Along with follicular unit monitoring, hair productivity matches much better than hair counts the perspective of clinical relevance. The new findings are in line with earlier publications, providing further scientific support against the prevailing dogma that miniaturised scalp follicles would be responsible for drug-induced hair regrowth. Accordingly, this unproven theory on “reversal” should be abandoned, unless duly documented and proven. Finally, we realise that surgeons and dermatologists involved in scalp hair follicle transplantation and drug trials still face an unanswered question: Where does the regrowing hair come from? We provide tentative answers and propose a speculative hypothesis in Supplement File 3 with baseline characteristics of follicular units that may point to a potential for drug-induced regrowth.

Material and methods

Subjects

Patients and healthy controls in cross-sectional studies

Non-invasive observational methods for scalp hair were applied in 497 patients who complained of stable or slowly progressive and chronic hair loss for more than 6 months and less than 15 years. All were seen with clean dry scalp hair by a single observer between 2006 and 2019. Their data have never been published before.

The clinician applied his original “listen, look and touch” approach[9]. Gentle hair pulling was systematically performed. Patient’s data were compared with functional data collected from 90 observations from healthy controls (52 male and 38 female). Because gender substantially affects clinical presentation, we detail female groups first and male groups next. From a total of 370 female patients with hair loss data, those with specific diagnoses such as trichotillomania, active inflammatory diseases such as alopecia areata or scarring disorders were excluded (66 females). Whenever required, scalp biopsies were taken for differential diagnosis.

Females maintaining a dense frontal fringe in contrast with the scalp located behind, i.e., on the top of the head, were classified as having PHL. Otherwise, they were rated as “no pattern” (NoP) or “Other”. The latter meant less clearly marked or even mixed distribution of hair densities. As an example, “Other” would be used in the case of combined male and female patterns and diffuse loss at the same time. In the case of patterning, the severity grades were based on cartoons derived from Ludwig’s classification[8] [Ludwig I-III; Figure 1]. These five categories help to split up all subsequent continuous data [scalp coverage scoring (SCS) and hair productivity].

Figure 1. Evaluation of hair loss by patients and clinician with our phototrichogram method and scalp coverage scoring. Figure 1 illustrates all the techniques used throughout this study. Figure 1A and B displays cartoons employed by investigator and patients. From normal coverage or no visible hair loss [Figure 1A; top left], the patients independently choose either no visible loss or FPHL split-up according to Ludwig stages [LI-LIII; bottom of Figure 1A] or MPHL [Hamilton stages HI-HV in Figure 1B]. Similarly, and without direct interaction with the patient’s record, the clinician classified subjects as having diffuse or patterned hair loss (PHL). The SCS [Figure 1C] was usually performed on the computer screen. This implies the subdivision of the image of the top of the head into 18 square fields surrounded by a circle, a symbolic outline of the head. With the hair combed as spokes of a wheel, SCS was evaluated in 2 different ways: first scoring the nine numbered fields that include top and vertex [Figure 1C, top; 1-9 bold] followed by the nine other fields with more lateral and anterior locations [Figure 1C, top; italic light]. Finally, on the image taken after parting hair along the midline, coverage was estimated in each of the four squares labelled p1-p4 [Figure 1C, bottom]. At the end of the clinical visit, the investigator selected a region of interest (ROI). This site served for detailed hair growth measurements employing the CE-PTG-EC [Figure 1D]. Our phototrichogram method is illustrated (modification of the original Figure 1 in the author’s publication to which we refer the interested reader[15,16]). Classical and novel processing methods are illustrated in greater detail in Figures 11 and 12. Exogen collection is part of our phototrichogram method, as shown in the lower half of Figure 1D where three loosely attached telogen bulbs were entrapped in the blue matrix examined under a stereomicroscope. The schematic view [bottom of Figure 1D; arrowheads] illustrates the same 3 exogen hairs: Exogen 1 was deeply set in the follicle at completion of telogen; Exogen 2 was moving upwards in the hair follicle; and Exogen 3 almost reached the scalp surface for release in the nearby future. Figure 1E shows clinical examples of male subjects with MPHL according to Hamilton’s scale with hair combed as spokes of a wheel (left to right; severity Grades I-V). For the correct interpretation of data from the clinical perspective, readers are invited to keep three things in mind: (1) The frontal hairline does not appear in the global view and, as a consequence, should not interfere with SCS; (2) The variable shape/size of the head does not interfere with SCS as the scalp areas explored in a given subject are stable over time; and (3) ROI is remote from the epicentre of the balding process (white dot usually on the right side of patient’s top of the head). FPHL: Female pattern hair loss; MPHL: male pattern hair loss; SCS: scalp coverage scoring, CE-PTG-EC: contrast-enhanced phototrichogram with exogen collection.

The pool of 304 females was compared with unaffected young healthy controls (15-20 years old) and split according to clinical pattern, severity and age. Besides 255 females with FPHL, i.e., LI (n = 135, 44-year-old), LII (n = 107, 45-year-old), and LIII (n = 13, 51-year-old), there were 39 showing no pattern (NoP; n = 39, 41-year-old) and a few remaining patients with a mixed condition grouped as “Other” (n = 10, 52-year-old). After excluding a small number of male subjects with specific disorders (n = 17), the remaining 110 males were split according to Hamilton’s classification with severity Grades I-V [HI-HV; Figure 1]. Male demographics with average age were as follows: HI (n = 6, 19-year-old), HII (n = 28, 21-year-old), HIII (n = 50, 34-year-old), HIV (n = 16, 38-year-old) and HV (n = 10, 39-year-old).

With a few exceptions, all participants completed a pre-printed questionnaire including self-estimation of hair loss. This was given on the first day of the consultation and should ideally be filled out before the second visit. Besides personal and family history and quality of life issues (not published herein), patients proceeded with self-estimation of their hair loss using the same cartoons as the clinical observer [Figure 1].

All patients underwent all clinical measurements and imaging methods reported in the next sections, the most important from the clinical-functional point of view being standardised global imaging combined with Contrast-Enhanced-Phototrichogram with Exogen-Collection (CE-PTG-EC), as illustrated in Figure 1 and published in detail previously[10,16].

Volunteers engaged in longitudinal drug trials

Images and unmodified source data were retrieved from three controlled assays.

One unpublished drug trial in MPHL evaluated daily application of a topical anti-androgen (multi-centre study, six months duration with evaluations at baseline, Month 3 and Month 6). The same analytical protocol as the one employed in the present study showed no statistically significant changes of hair productivity over time in any treatment group. We retrieved the global clinical scoring generated on 27 MPHL subjects followed in our evaluation centre. In total, 81 SCS records were used to test reproducibility through test-retest analysis.

From our oral study on finasteride (Propecia™, 1 mg/day) with topical application of either minoxidil 5% (Alostil™, 1 mL/day) or a placebo lotion during the initial 3 months[13], we selected the best responder with acute changes of hair cycling (switch-on of growth during topical treatment and switch-off after arrest of topical applications). Source global images were re-evaluated, and detailed hair growth parameters were translated into hair productivity, as explained below.

Finally, we re-examined high resolution processed images of one volunteer with stabilised MPHL [third year daily intake of oral finasteride (1 mg/day)]. While test scalp site remained unresponsive to a six-month assay with the LASER-comb[17], this subject mounted a rapid response to the topical application of minoxidil (5%, 1 mL, 1 × /day). We tracked all calibrated hair on a follicular basis from baseline until the end of the third month of combined treatment.

Ethics

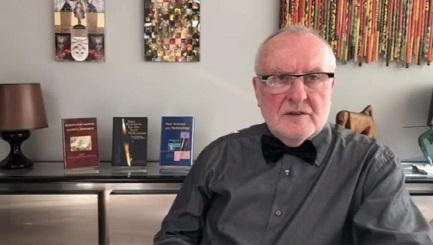

All study protocols and measurement methods (experiments including healthy volunteers, patients and drug trials) were approved by the local board of Ethical Commission for Clinical Investigation, implying that identification of participants would not be possible by any means. Facial recognition would be impossible and parental permission was obtained for the youngest subjects (16 years).

Imaging technology

Global images

All patients presented with clean dry hair after their latest shampoo on the morning of the clinical visit. The clinician estimated hair loss, actual presence of a pattern and severity grades. The aspect of the top of the head was recorded employing an original imaging system. After correct positioning of the customised stereotactic headgear and after switching on the “build-in-light-box”, standard images were taken at fixed angle and distance[10,15]. The procedure included dry scalp hair combing in two different ways: spokes of a wheel [Figure 1] and midline parting [Figures 2 and 3].

Figure 2. Images from top of the head in females. The top of the head is illustrated in seven females complaining of hair loss. The upper panels show clinical perception as: “No Pattern” (left; 1 case); FPHL graded as LI (1 case), LII (2 cases) or LIII (2 cases) and one subject with no clear evidence for patterning (Other; 1 case). From top to bottom, the panels show hair combed in spokes of a wheel, with a parted midline and with the clipped hair site. The latter is highlighted as a white empty circle. The region of interest (ROI) outline, located at a distance from the epicentre, was then transposed on the other views (top 2 rows). Note again that top of the head views did not include the frontal margin, which does not influence the scalp coverage scoring (SCS). When required according to the study protocol, the clinician measured scalp coverage in vivo (SCS in vivo; described in the next section), while charge coupled device images (source document) were used at a later stage to evaluate scalp coverage scoring on the computer screen (see next section). A third view was recorded to document precisely the topography of the ROI that was selected by the clinician not only at the preferred location, i.e., leading edge of the balding process, but also in agreement with the acceptance by the patient. This ROI might be either clinically unaffected or clinically invaded by the extension of a clearly visible balding process, as illustrated typically in HIII-HV [Figure 1] and LII and LIII [Figure 2]. The ROI was subject to detailed scalp hair functional evaluation with our phototrichogram method (as detailed below). FPHL: Female pattern hair loss.

Figure 3. Performing scalp coverage scoring (SCS) in vivo and on computer screen. For illustration purposes, a female patient seen recently agreed to be part of this project showing how SCS can be performed in vivo. Figure 3A shows the investigator’s hand (a1) while adjusting the handheld transparency [(a2) carved out 18 squares] to the frontal headgear worn by the patient (a3). The facial mask indicates that the image was taken during the 2020 SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. The observer starts scoring by analogy with the scale of “difficulty” [shown in (a4)]. Schematically, Figure 3B symbolises the eye of the clinician (b1) who looks through a carved-out transparency (b2). This particular SCS grid illustrates how the clinician should focus on the midline fields in same patient (b3) while referring to a scale of “difficulty”. The latter (b4) displays a series of shaded areas where “5” means “it is very difficult to observe the scalp skin through the hair” while “0” means “no difficulty at all observing the skin through the hair”. We further illustrate the influence of hairstyling on performing SCS on the top of the head of a male patient. This male patient with Hamilton II appeared already with hair combed as spokes of a wheel [Figure 1E, first case on the left graded as II]. Figure 3C shows the same but enlarged image along with 18 numbered fields of the grid (bold and paler italic numbers; left). After combing with midline parting, a new SCS was performed [Figure 3D; p1-p4]. While scalp skin can be barely perceived in Figure 3C (SCS range 4-5), the scalp skin was much more easily visible in between the hair in Figure 3D (SCS range 3-4).

When required according to the study protocol, the clinician measured scalp coverage in vivo (SCS in vivo; described in the next section) while Charge Coupled Device-images (CCD; source document) were used at a later stage to evaluate scalp coverage scoring on the computer screen (see next section). A third view was recorded to document precisely the topography of the “Region Of Interest” (ROI) that was selected by the clinician not only at the preferred location, i.e., leading edge of the balding process, but also in agreement with the acceptance by the patient. This ROI might be either clinically unaffected or clinically invaded by the extension of a clearly visible balding process as illustrated typically in HIII-HV [Figure 1] and LII and LIII [Figure 2]. The ROI was subject to detailed scalp hair functional evaluation with our phototrichogram method (as detailed below).

Scalp coverage scoring

The SCS was validated in 2006[18], i.e., before launching this study.

Briefly, a standardised transparent grid was superimposed on the global view of the top of the head appearing on the computer screen. The dimensions were secured with stereotactic headgear worn while images were captured; this objective ruler served during all subsequent imaging procedures. The templates outlined a total of 18 squares [Figures 1 and 2]. Each square in its bi-dimensional projection on a curved surface represents a scalp area approximately 16 cm2 (4 cm × 4 cm). Every single square field was scored (from 0 to 5) against a built-in scale (from 5 to 0). The scale helps the clinician during the scoring. SCS of a given field represents the difficulty to observe scalp skin in between the hair: a score of 5 means “very difficult” while 0 means “not difficult at all”. As SCS is obviously an observer-dependent parameter, trained expert observers refer to an abstract mental representation of “difficulty”.

In the present study, firstly, SCS was performed on the top of the head with hair combed in spokes of a wheel: Score the nine fields remote from the frontal hair line and closer to the vertex [Figure 1C, top; 1-9; bold]. Proceed with scoring on the nine remaining squares located at the periphery [Figure 1C, top; 1-9; light italic].

The sum of scores on the vertex and the sum of scores on periphery were recorded separately.

Secondly, SCS was performed on the scalp view with hair parted along the midline, a routine standardised procedure introduced during clinical trials[19]. The four squares located on the midline [Figure 1C, bottom; p1-p4 bold] were analysed and the sum of scores in these four fields was recorded.

More work on validation of new experts for correct application of SCS method is planned (see Acknowledgements Section), but, once trained, observers clearly did not require an infinite variety of scales.

SCS in vivo followed the same guidelines with real time observation of the top of the head through a handheld device, as shown in Figure 3.

SCS on midline-parted hair is an innovative clinical procedure that reduced the influence of hairstyle on SCS, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, while alterations in the frontal hair line (not part of SCS) would be considered as “earliest” steps into patterning. A pattern with normal SCS might help find the most specific analytical hair diagnostic criterion, if any, in the analytical approach.

In fact, hairstyle means cumulative growth and depends on the length reached after the last haircut; thus, a very short hair cut by hairdresser is a limitation to correct performance with SCS, and this will be illustrated during longitudinal studies.

Contrast enhanced phototrichogram with exogen collection

The CE-PTG-EC procedure including exogen collection, henceforth referred to as our phototrichogram, has been described and validated previously[20,21] against serial sectioning of scalp biopsies from balding males. Our phototrichogram exhaustively explores structural and functional hair variables in the region of interest (ROI).

The scalp spot was usually 12-17 cm above the middle of the right eyebrow, most often between 2 and 4 cm to the right-hand side of the scalp midline, as illustrated in Figures 1-3.

Before selecting this spot ideally at the leading edge of the balding process, we took into account the patients’ willingness as it relates to personal hairstyling.

Images were captured employing a LED equipped lens mounted on a CCD camera (Dermlight™). A typical sequence consisted of a first visit (t0) with clipping of the scalp hair, dyeing of the clipped spot and image capturing, followed by a second visit (t2; two days after t0) during which a new image was captured immediately after a second hair dye session and after exogen collection as described below.

Exogen hair counts

As stated above, phototrichogram implies that the ROI was subject to non-invasive extraction of the shedding hair employing a specific validated exogen removal process[22]. The non-invasively entrapped exogen hairs were examined under a stereomicroscope at 40× magnification and reported as units/cm2. No attempt was made to calibrate precisely the diameter of the collected exogen hair.

Hair variables involved in the measurement of scalp hair follicle productivity

Unless specifically mentioned, absolute numbers per unit area (1 cm2) are given preferably throughout this paper. Patient data were compared with reference values obtained with identical technology in healthy controls under known conditions of accuracy (technological variability < 3%[10,16]).

Customised software was developed to perform computer-assisted image analysis (CAIA) on manually processed images. This included the perfect overlay of each calibrated individual fibre at t0 and t2. Then CAIA generated many hair parameters based on counts per unit area, diameter and growth rates.

The increase in length of individual hair fibres was established on stubbles seen at t0 and t2. By dividing the increase in length of individual hair fibres by the exact time elapsed between t0 and t2, we measured linear hair growth rate (LHGR) as µm/24 h. Each hair fibre was also calibrated using rulers within the range from < 20 to ≥ 100 µm (steps of 10 µm). Scalp hairs were categorised from the thickest to thinnest miniature hair. The latter comprised: (a) nanohair with a diameter < 20 µm (no growth staging was attempted on nanohair); and (b) miniature, which also included vellus and/or vellus-like hair, as any hair thicker than a nanohair with a diameter < 40 µm.

It is generally accepted that thicker and deeply set follicular roots would produce terminal hair during their growth phase, i.e., anagen. Herein, we report growth for all categories (except nanohair) taken separately from 20 µm to the terminal fibres with diameters ≥ 60 µm. Subgroups such as 20-30 µm are quoted as miniaturising while 40-50 µm are quoted as intermediate hair.

Linear hair growth rate discriminates between resting (telogen) and anagen growth staging

As with diameters, there was also a threshold for growth staging. Anagen stages were statistically distinct from non-growing stages (catagen-telogen) based on the bimodal distribution of elongation per time unit. The threshold between growth and rest phases was established on data collected in healthy controls, i.e., linear hair growth rate (LHGR, µm/24 h).

Compound Index of Hair Growth and Time To Complete Coverage

Productivity of individual hair follicles integrating growth rate and diameter generated the compound index of hair growth (CIHG). The implementation of density generates a cumulative index of growth that includes all growing follicles. The relative value of the latter reflects the fraction of scalp area under investigation that would be covered by daily hair growth on that very site. Calculation encompassed all growing hair in all diameter classes (classes taken one by one from thinnest ≥ 20 µm and < 30 µm to the largest ≥ 100 µm diameters) along with their respective average LHGR:

CIHG = [number anagen per unit area (n/cm2) × average linear growth rate (µm/24 h) × diameter (µm)].

The average value of CIHG in patients can be expressed relative to the surface of the ROI. We report this in our cross-sectional study as well as during longitudinal studies or as it relates to a control group.

Nevertheless, while CIHG remains an excellent techno-scientific parameter[12,13], we devised a more practical way of expression. The purpose was to offer practising dermatologists and patients a dimension intuitively known in our daily life, i.e., “Time To Complete Coverage” (TTCC). The latter value was conceived as follows: If every single growing hair appearing on the scalp surface were placed flat on the scalp surface, perfectly adjacent to its neighbours, how much time would it take to cover the ROI completely?

During preliminary assays, we noted that the volumetric calculations were not mandatory. Hair diameter - in the present experimental setting - is related to the width appearing in the bidimensional image against the scalp surface.

The precise surface of the field under investigation was based on the points of origin of the hair fibre as they relate to the individual follicular units (FU). Each stubble exits from an acro-infundibulum and the scalp area outlined by all and any measured follicular unit was established by the CAIA as being 100%, i.e., an exhaustive measure of FU density (FUD).

The reverse of the relative area covered per day [(%/day)−1] reflects the time (days) required to hit 100% coverage (TTCC). As an example, our calculated TTCC in healthy controls with an approximate 5% CIHG means that it would take 20 days to hit the “100% healthy control TTCC”. Comparatively, the TTCC in a balding subject with 2% daily coverage would be 50 days.

Innovative approaches during longitudinal studies

Global SCS (variation over time and reproducibility)

SCS was performed three times on 27 subjects during a six-month period. Hence, triplicate observations with 81 SCS data could be tested for possible variation over time. As the SCS rating was made one image at a time, images were randomised and the observer was considered as blinded to the time. The SCS was performed before unsealing the envelopes containing the treatment codes and, as a consequence, before the eventual efficacy of the test compounds would be known.

Today, from our analytical procedures, we acknowledge the absence of statistically significant changes of hair productivity with these test compounds (unpublished data). We draw the attention of clinicians to the following: if SCS were performed during longitudinal studies, it would consistently match identical fields as those already outlined at baseline.

Correlation of SCS with acute fluctuations of hair follicle productivity

As a technological challenge for the SCS, we selected the best responder from a previously published trial and calculated his time to complete coverage (TTCC) from the published hair follicle productivity (CIHG)[13]. We correlated the ensuing time to complete coverage with global clinical images recorded during the year preceding the entry into the drug trial protocol until its end. Compliance was rated as excellent until completion at the 24th month on the drug. Baseline SCS and analytical procedures followed the protocol of combined drugs (oral finasteride and topical lotion containing 5% minoxidil) during the initial three months, followed by monotherapy (finasteride 1 mg/day) until completion. We refer the interested readers to previous papers regarding the SCS values fitting expert ratings for drug filing at the FDA[18] and for measuring subjective satisfaction with scalp hair responses[10,15].

Tracking of individual hair follicle productivity during drug trials

We evaluated a single subject with MPHL known to be on chronic oral finasteride[23] who completed a six-month LASER-comb study protocol[17]. The subject volunteered for an extended three months of monitoring of the same scalp sites. After two phototrichograms performed at one-week interval (baseline), the volunteer entered the three-month study aiming at measuring biological potential for hair regrowth. Along with maintenance of oral drug intake, the subject applied daily a single spray of minoxidil 5% lotion on the monitored test site (< 1 cm2). The compliance of daily oral drug intake and topical application of a drop of minoxidil lotion (5%) was rated higher than 99% on the basis of a hand-ticked diary.

The technician involved in image processing was unaware of the ongoing treatments.

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether minoxidil 5%, once a day, would improve the hair loss under stabilising effects of long-term oral treatment (over three years of daily intake of finasteride, 1 mg/day; Propecia™) while, in the same site and same subject, a six months controlled use of LASER-comb had no significant effect on hair growth[17].

To visualise the individual hair productivity, an innovative dot mapping technique was developed.

Accordingly, the original hand-processed phototrichogram images were subject to the novel dot-mapping technique. The latter first exhaustively established the FUD in the monitored scalp field. The FUD map was exhaustively completed through back-and-forth travelling along the three-month time-scale in images probing the ROI.

The FUD map was then transposed as a background on each phototrichogram and allowed tracking of the follicular unit responses after one and three months of combined treatment.

The next step was to overlay on each FUD the productivity of individual hair follicle on a hair-to-hair basis.

The point of exit from the follicular opening of each growing segment was marked by a calibrated dot employing a predefined colour code: magenta, 20-30 µm; blue, 40-50 µm; green, 60-70 µm; and yellow, ≥ 80 µm. The productivity was symbolised by the diameter of the dots: yellow > green > blue > magenta. This correlates but does not reflect exactly the product of diameter × linear growth rate. For an improved readability, we organised and highlighted productivity with hair dots that would be large enough to be seen in the published paper and, at the same time, not overlapping between them but remaining clustered to the productive FUD.

Finally, each FUD was numbered to organise the individual hair data and keep a record of changes occurring over time providing data and statistics reflecting changes of hair growth on a follicular basis.

Descriptive statistics and statistical analyses

Cross-sectional studies

The subjective perception of hair loss that brought the patient to the clinic, the cartoons selected by the patients and the ensuing clinical diagnosis made by the observer were considered as categorical or discontinuous data, i.e., undisputable. The investigator did not communicate his selection of severity to the patient. Consistency of self-evaluation of severity and its deviations from the grades established by the clinical observer are commented as relative frequencies of subjects attributing “identical” or “different scores” but not reported as averages.

The clinical diagnosis served to split up all subsequent continuous data (SCS and all hair measurements).

Descriptive statistics of absolute values (average and standard deviation of samples) were preferred and always displayed versus healthy controls. For clinical use, relative frequencies and proportions are reported in two ways: as percentiles of patients lower than P05 or exceeding the P95 value found in controls or as the actual values in patient groups expressed as a percentage of reference values [for example, averages in patients as a per cent of control values or per cent of the measured value relative to the highest possible value (maximum)]. Relative values are identified clearly and always given comparatively to absolute values.

After checking normality of the data distribution, a global analysis of variance (ANOVA; Statview®) was used for comparing all source data, i.e., continuous parameters in healthy controls vs. patients or between patient subgroups.

Tables 1-8 report clearly on the global statistically significant differences vs. controls when P values were P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, symbolised, respectively, with *, ** and ***. Once global significance of differences was established, the Bonferroni/Dunn test was used to evaluate statistically significant differences between each clinical category vs. gender-matched healthy controls, as symbolised by “S”.

Descriptive statistics of absolute hair densities along with categories of hair fibre diameter

| Density according to Diameter | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | age | Parameter | Nanos (< 20 µm) | 20 µm | 30 µm | 40 µm | 50 µm | ≥ 60 µm | Total | |||||||

| P value | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | |||||||||

| F CONS | 15-20 | average | 6 | *** | 18 | * | 48 | ** | 45 | *** | 78 | *** | 118 | *** | 315 | *** |

| st dev | 5 | 8 | 15 | 22 | 30 | 53 | 31 | |||||||||

| NoP | 40 | average | 23 | S | 13 | 24 | S | 18 | S | 29 | S | 163 | S | 250 | S | |

| 8 | st dev | 26 | 11 | 17 | 16 | 25 | 59 | 60 | ||||||||

| LI | 44 | average | 28 | S | 18 | 33 | S | 30 | S | 44 | S | 112 | 239 | S | ||

| 13 | st dev | 21 | 16 | 27 | 22 | 31 | 61 | 52 | ||||||||

| LII | 45 | average | 36 | S | 21 | 34 | S | 31 | S | 29 | S | 58 | S | 176 | S | |

| 15 | st dev | 25 | 15 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 37 | 52 | ||||||||

| LIII | 48 | average | 53 | S | 23 | 24 | S | 20 | S | 16 | S | 36 | S | 120 | S | |

| 13 | st dev | 63 | 21 | 14 | 12 | 15 | 22 | 33 | ||||||||

| Other | 52 | average | 23 | 20 | 33 | 28 | 35 | S | 102 | 220 | S | |||||

| 15 | st dev | 11 | 15 | 27 | 17 | 16 | 71 | 51 | ||||||||

| M CONS | 15-20 | average | 5 | *** | 16 | ** | 27 | *** | 24 | NS | 42 | 173 | *** | 290 | *** | |

| st dev | 5 | 11 | 14 | 16 | 26 | 45 | 60 | |||||||||

| HI | 26 | average | 27 | 12 | 21 | 37 | 57 | 127 | 254 | |||||||

| 5 | st dev | 19 | 7 | 13 | 29 | 35 | 45 | 71 | ||||||||

| HII | 27 | average | 30 | S | 14 | 18 | 23 | 37 | 131 | S | 225 | S | ||||

| 5 | st dev | 18 | 9 | 13 | 18 | 27 | 47 | 47 | ||||||||

| HIII | 34 | average | 35 | S | 20 | 32 | 32 | 38 | 92 | S | 217 | S | ||||

| 9 | st dev | 21 | 13 | 24 | 20 | 17 | 46 | 51 | ||||||||

| HIV | 39 | average | 37 | S | 21 | 22 | 29 | 32 | 59 | S | 164 | S | ||||

| 10 | st dev | 34 | 16 | 10 | 16 | 17 | 29 | 41 | ||||||||

| HV | 39 | average | 45 | S | 31 | S | 48 | S | 34 | 32 | 39 | S | 185 | S | ||

| 9 | st dev | 27 | 17 | 27 | 22 | 11 | 24 | 60 | ||||||||

Percentiles of hair densities along with categories of fibre diameter

| Density according to Diameter (Percentile on absolute values) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Number of CE-PTG-EC | Parameter | Nanos | Miniaturised | Intermediate | Terminal | Total | ||

| Percentile | <20μm | 20μm | 30μm | 40μm | 50μm | ≥60μm | |||

| F CONS | 38 | P 05 | 0 | 3 | 30 | 18 | 28 | 36 | 261 |

| P 95 | 17 | 33 | 80 | 106 | 120 | 228 | 374 | ||

| NoP | 39 | <P05 | 0 | 23 | 69 | 59 | 69 | 3 | 56 |

| >P95 | 49 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 3 | ||

| LI | 133 | <P05 | 0 | 15 | 52 | 32 | 36 | 12 | 65 |

| >P95 | 61 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | ||

| LII | 106 | <P05 | 0 | 10 | 56 | 28 | 51 | 33 | 94 |

| >P95 | 72 | 21 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| LIII | 14 | <P05 | 0 | 14 | 71 | 36 | 79 | 57 | 100 |

| >P95 | 79 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other | 10 | <P05 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 20 | 30 | 30 | 60 |

| >P95 | 60 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| M CONS | 51 | P 05 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 14 | 97 | 198 |

| P 95 | 19 | 42 | 55 | 58 | 97 | 241 | 402 | ||

| HI | 6 | <P05 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| >P95 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 17 | 0 | 0 | ||

| HII | 28 | <P05 | 0 | 11 | 29 | 4 | 18 | 32 | 21 |

| >P95 | 71 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | ||

| HIII | 50 | <P05 | 0 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 18 | 62 | 36 |

| >P95 | 74 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| HIV | 16 | <P05 | 0 | 6 | 13 | 0 | 19 | 94 | 82 |

| >P95 | 63 | 19 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| HV | 10 | <P05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 60 |

| >P95 | 80 | 20 | 30 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Descriptive statistics of anagen and telogen hair and diameter

| Growth according to diameter | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Age | Parameter | Anagen ≥ 20 µm | Telogen ≥ 20 µm | Anagen ≥ 30 µm | Telogen ≥ 30 µm | Anagen ≥ 40 µm | Telogen ≥ 40 µm | Anagen ≥ 50 µm | Telogen ≥ 50 µm | Exogen Tot | |||||||||

| P value | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | |||||||||||

| F CONS | 15-20 | average | 271 | *** | 37 | NS | 260 | *** | 29 | NS | 223 | *** | 23 | * | 185 | *** | 16 | ** | 3 | *** |

| st dev | 26 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 27 | 19 | 35 | 15 | 4 | |||||||||||

| NoP | 40 | average | 215 | S | 35 | 208 | S | 28 | 189 | S | 25 | 174 | 21 | 3 | ||||||

| 8 | st dev | 58 | 20 | 56 | 19 | 47 | 19 | 45 | 19 | 3 | ||||||||||

| LI | 44 | average | 197 | S | 41 | 189 | S | 32 | 164 | S | 26 | 140 | S | 19 | 4 | |||||

| 13 | st dev | 49 | 23 | 47 | 19 | 48 | 15 | 52 | 13 | 5 | ||||||||||

| LII | 45 | average | 133 | S | 42 | 126 | S | 28 | 103 | S | 20 | 79 | S | 13 | 8 | S | ||||

| 15 | st dev | 47 | 23 | 43 | 17 | 36 | 12 | 34 | 10 | 7 | ||||||||||

| LIII | 48 | average | 80 | S | 40 | 72 | S | 24 | 58 | S | 18 | 44 | S | 11 | 9 | S | ||||

| 13 | st dev | 29 | 21 | 26 | 15 | 23 | 11 | 22 | 9 | 7 | ||||||||||

| Other | 52 | average | 166 | S | 53 | 156 | S | 43 | 138 | S | 34 | 118 | S | 24 | 4 | |||||

| 15 | st dev | 47 | 35 | 47 | 28 | 52 | 20 | 59 | 14 | 2 | ||||||||||

| M CONS | 15-20 | average | 230 | *** | 54 | *** | 223 | *** | 44 | *** | 207 | *** | 37 | ** | 189 | *** | 30 | * | 2 | *** |

| st dev | 44 | 36 | 44 | 29 | 38 | 24 | 32 | 20 | 2 | |||||||||||

| HI | 26 | average | 214 | 39 | 209 | 33 | 194 | 23 | 167 | 13 | 6 | |||||||||

| 5 | st dev | 66 | 12 | 67 | 14 | 59 | 9 | 44 | 13 | 5 | ||||||||||

| HII | 27 | average | 169 | S | 55 | 163 | S | 47 | 151 | S | 40 | 135 | S | 32 | 5 | |||||

| 5 | st dev | 45 | 30 | 42 | 26 | 37 | 23 | 35 | 22 | 5 | ||||||||||

| HIII | 34 | average | 138 | S | 78 | S | 130 | S | 65 | S | 116 | S | 50 | 99 | S | 34 | 6 | S | ||

| 9 | st dev | 38 | 37 | 38 | 31 | 37 | 24 | 38 | 20 | 5 | ||||||||||

| HIV | 39 | average | 96 | S | 68 | 92 | S | 51 | 83 | S | 36 | 68 | S | 22 | 8 | S | ||||

| 10 | st dev | 24 | 34 | 25 | 26 | 26 | 18 | 25 | 15 | 9 | ||||||||||

| HV | 39 | average | 77 | S | 107 | S | 68 | S | 85 | S | 56 | S | 61 | 45 | S | 38 | 10 | S | ||

| 9 | st dev | 30 | 52 | 29 | 45 | 26 | 29 | 24 | 20 | 9 | ||||||||||

Percentiles of anagen and telogen hair and diameter

| Growth according to diameter (Percentile on absolute values) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Number of CE-PTG-EC | Parameter | Anagen | Telogen | Anagen | Telogen | Anagen | Telogen | Anagen | Telogen | Exogen |

| Percentile | ≥20μm | ≥20μm | ≥30μm | ≥30μm | ≥40μm | ≥40μm | ≥50μm | ≥50μm | Tot | ||

| F CONS | 38 | P 05 | 228 | 11 | 218 | 8 | 157 | 5 | 96 | 2 | 0 |

| P 95 | 315 | 92 | 311 | 88 | 263 | 76 | 228 | 63 | 14 | ||

| NoP | 39 | < P05 | 64 | 5 | 67 | 10 | 13 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| >P95 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 3 | ||

| LI | 133 | < P05 | 70 | 3 | 71 | 5 | 39 | 4 | 20 | 8 | 0 |

| >P95 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 5 | ||

| LII | 106 | < P05 | 95 | 1 | 96 | 4 | 92 | 3 | 75 | 9 | 0 |

| >P95 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | ||

| LIII | 14 | < P05 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 7 | 100 | 7 | 100 | 14 | 0 |

| >P95 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | ||

| Other | 10 | < P05 | 90 | 0 | 100 | 10 | 50 | 10 | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| >P95 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| M CONS | 51 | P 05 | 146 | 12 | 141 | 10 | 137 | 8 | 127 | 4 | 0 |

| P 95 | 301 | 117 | 295 | 99 | 272 | 81 | 246 | 75 | 7 | ||

| HI | 6 | < P05 | 17 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 17 | 17 | 0 |

| >P95 | 17 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | ||

| HII | 28 | < P05 | 32 | 4 | 32 | 4 | 39 | 0 | 43 | 0 | 0 |

| >P95 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 32 | ||

| HIII | 50 | < P05 | 64 | 2 | 60 | 0 | 68 | 0 | 74 | 2 | 0 |

| >P95 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 4 | 40 | ||

| HIV | 16 | < P05 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 13 | 0 |

| >P95 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 | ||

| HV | 10 | < P05 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| >P95 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 50 | ||

Descriptive statistics of productivity of scalp hair

| Anagen % | LHGR (µm/day) | CIHG (µm2/ [cm2 x day]) | CIHG (Tot) | TTCC | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Age | Parameter | A6% 20-30 µm | A6% 40-50 µm | A6% ≥ 60 µm | LHGR 20-30 µm | LHGR 40-50 µm | LHGR ≥ 60 µm | CIHG 20-30 µm | CIHG 40-50 µm | CIHG ≥ 60 µm | Area % | Days | |||||||||||

| P value | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | |||||||||||||

| F CONS | 15-20 | average | 69 | *** | 88 | *** | 96 | * | 273 | ** | 351 | *** | 388 | NS | 442 687 | *** | 1 424 975 | *** | 2 991 946 | *** | 4.37 | *** | 21.26 | *** |

| st dev | 17 | 12 | 5 | 33 | 40 | 46 | 227 593 | 632 903 | 1 542 453 | 1.15 | 5.26 | |||||||||||||

| NoP | 40 | average | 62 | 80 | 91 | 250 | 311 | S | 376 | 188 977 | S | 600 812 | S | 4 274 687 | S | 4.54 | 22.33 | |||||||

| 8 | st dev | 21 | 13 | 7 | 33 | 38 | 48 | 150 181 | 524 192 | 1 882 783 | 1.75 | 11.18 | ||||||||||||

| LI | 44 | average | 59 | 81 | 92 | 256 | 321 | S | 371 | 235 752 | S | 930 922 | S | 2 837 955 | 3.50 | S | 28.95 | |||||||

| 13 | st dev | 20 | 13 | 6 | 38 | 52 | 76 | 228 805 | 646 937 | 1 736 099 | 1.49 | 13.56 | ||||||||||||

| LII | 45 | average | 53 | S | 79 | S | 92 | 247 | S | 307 | S | 362 | 214 260 | S | 693 397 | S | 1 442 349 | S | 1.81 | S | 50.26 | S | ||

| 15 | st dev | 19 | 14 | 9 | 37 | 50 | 72 | 197 369 | 488 210 | 1 024 165 | 1.02 | 22.32 | ||||||||||||

| LIII | 48 | average | 42 | S | 63 | S | 89 | 240 | 297 | S | 330 | 163 931 | S | 350 939 | S | 915 987 | S | 0.86 | S | 88.79 | S | |||

| 13 | st dev | 17 | 25 | 10 | 50 | 60 | 112 | 191 062 | 266 404 | 567 633 | .77 | 43.55 | ||||||||||||

| Other | 52 | average | 56 | 71 | S | 92 | 227 | S | 291 | S | 344 | 178 123 | S | 600 812 | S | 2 445 954 | 2.8 | S | 42.3 | S | ||||

| 15 | st dev | 15 | 17 | 5 | 20 | 33 | 42 | 113 932 | 524 192 | 1 909 572 | 1.75 | 26.19 | ||||||||||||

| M CONS | 15-20 | average | 53 | *** | 73 | *** | 91 | *** | 258 | *** | 324 | *** | 379 | *** | 35 110 | *** | 169 797 | *** | 4 481 186 | *** | 4.81 | *** | 19.62 | *** |

| st dev | 17 | 8 | 7 | 29 | 39 | 47 | 33 187 | 150 498 | 1 341 237 | 1.22 | 5.58 | |||||||||||||

| HI | 26 | average | 56 | 78 | 94 | 281 | 344 | 405 | 151 478 | S | 1 219 377 | S | 3 429 481 | 4.33 | 21.17 | |||||||||

| 5 | st dev | 16 | 18 | 6 | 29 | 37 | 29 | 94 265 | 906 206 | 1 226 371 | 1.03 | 4.07 | ||||||||||||

| HII | 27 | average | 51 | 66 | 84 | 265 | 323 | 377 | 127 431 | S | 634 087 | S | 3 173 898 | S | 3.46 | S | 28.11 | |||||||

| 5 | st dev | 23 | 18 | 10 | 32 | 42 | 46 | 98 522 | 504 651 | 1 458 813 | 1.26 | 10.42 | ||||||||||||

| HIII | 34 | average | 45 | 57 | S | 81 | S | 239 | S | 291 | S | 334 | S | 142 807 | S | 554 870 | S | 1 912 145 | S | 2.10 | S | 44.70 | S | |

| 9 | st dev | 17 | 17 | 13 | 28 | 35 | 59 | 80 127 | 333 062 | 1 199 445 | 1.15 | 20.62 | ||||||||||||

| HIV | 39 | average | 31 | S | 55 | S | 82 | 230 | S | 284 | S | 336 | S | 89 085 | 487 905 | S | 1 162 901 | S | 1.13 | S | 68.75 | S | ||

| 10 | st dev | 15 | 20 | 12 | 22 | 31 | 44 | 34 745 | 306 184 | 701 928 | 0.72 | 28.64 | ||||||||||||

| HV | 39 | average | 29 | S | 42 | S | 75 | S | 218 | S | 258 | S | 291 | S | 122 295 | S | 297 128 | 663 016 | S | 0.6 | S | 119.90 | S | |

| 9 | st dev | 13 | 21 | 19 | 27 | 39 | 45 | 66 915 | 114 144 | 545 567 | 0.84 | 60.70 | ||||||||||||

Percentiles of productivity of scalp hair

| Anagen % | LHGR (μm/day) | CIHG (μm2 / [cm2 x day] ) | CIHG (Tot) | TTCC | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Number of CE-PTG-EC | Parameter | A6% | A6% | A6% | LHGR | LHGR | LHGR | CIHG | CIHG | CIHG | Area% | days |

| Percentile | 20-30μm | 40-50μm | ≥60μm | 20-30μm | 40-50 μrn | ≥60μm | 20-30μm | 40-50μm | ≥60μm | ||||

| F Cons | 38 | P 05 | 34 | 52 | 83 | 228 | 268 | 282 | 166 805 | 258 801 | 817 639 | 3 | 14 |

| P 95 | 92 | 99 | 100 | 328 | 399 | 460 | 914 684 | 2 363 098 | 6 589 147 | 7 | 31 | ||

| NoP | 39 | <P05 | 10 | 5 | 15 | 28 | 15 | 0 | 51 | 21 | 3 | 10 | 8 |

| >P95 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 13 | 8 | 10 | ||

| LI | 133 | <P05 | 11 | 3 | 7 | 25 | 11 | 5 | 44 | 10 | 14 | 35 | 1 |

| >P95 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 35 | ||

| LII | 106 | <P05 | 19 | 2 | 11 | 29 | 20 | 9 | 49 | 14 | 34 | 82 | 0 |

| >P95 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 81 | ||

| LIII | 14 | <P05 | 43 | 43 | 36 | 50 | 21 | 14 | 71 | 43 | 57 | 100 | 0 |

| >P95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| Other | 10 | <P05 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 50 | 30 | 0 | 60 | 10 | 30 | 50 | 0 |

| >P95 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| M Cons | 51 | P 05 | 28 | 39 | 77 | 213 | 258 | 303 | 5 102 | 22 475 | 2 353 961 | 3 | 14 |

| P 95 | 85 | 98 | 100 | 315 | 390 | 441 | 111 269 | 580 467 | 6 547 677 | 7 | 34 | ||

| HI | 6 | <P05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| >P95 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 33 | 17 | 0 | 50 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| HII | 28 | <P05 | 11 | 4 | 18 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 32 | 21 | 0 |

| >P95 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 39 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 21 | ||

| HIII | 50 | <P05 | 10 | 16 | 26 | 10 | 16 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 74 | 70 | 0 |

| >P95 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 70 | ||

| HIV | 16 | <P05 | 38 | 19 | 25 | 19 | 13 | 19 | 6 | 0 | 94 | 100 | 0 |

| >P95 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| HV | 10 | <P05 | 60 | 60 | 30 | 70 | 50 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 |

| >P95 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

Descriptive statistics of scalp coverage scores and percentiles of SCS in controls and deviations in patients

| SCS (absolute arbitrary units) | SCS (relative % of Max) | SCS (Percentile on arbitrary units) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Age | Field | Vertex | Crown | Mid-parting | Vertex | Crown | Mid-parting | Vertex | Crown | Mid-Parting | ||||

| P value | P | P | P | Max. 45 | Max. 45 | Max 20 | Percentile | ||||||||

| F CONS | 15-20 | 45 | *** | 45 | *** | 19 | *** | 99 | 99 | 97 | P05 | 44 | 44 | 19 | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | P95 | 45 | 45 | 20 | |||||||||

| NoP | 40 | 44 | 45 | 18 | 98 | 100 | 92 | < P05 | 31 | 0 | 69 | ||||

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | > P95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| LI | 44 | 42 | S | 45 | 16 | S | 93 | 100 | 82 | < P05 | 68 | 1 | 91 | ||

| 13 | 2 | 0 | 2 | > P95 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||

| LII | 45 | 38 | S | 44 | 13 | S | 84 | 98 | 64 | < P05 | 93 | 18 | 100 | ||

| 15 | 5 | 2 | 3 | > P95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| LIII | 48 | 30 | S | 39 | S | 9 | S | 68 | 87 | 45 | < P05 | 100 | 71 | 100 | |

| 13 | 8 | 7 | 4 | > P95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Other | 52 | 40 | S | 44 | 16 | S | 89 | 98 | 79 | < P05 | 70 | 20 | 80 | ||

| 15 | 5 | 2 | 3 | > P95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| M CONS | 15-20 | 44 | *** | 44 | *** | 19 | *** | 98 | 98 | 97 | P05 | 44 | 44 | 19 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | P95 | 45 | 45 | 20 | |||||||||

| HI | 26 | 44 | 45 | 17 | 98 | 100 | 87 | < P05 | 33 | 0 | 83 | ||||

| 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | > P95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| HII | 27 | 42 | 44 | 17 | S | 93 | 98 | 85 | < P05 | 50 | 7 | 82 | |||

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | > P95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| HIII | 34 | 39 | S | 43 | 14 | S | 87 | 96 | 71 | < P05 | 78 | 24 | 92 | ||

| 9 | 6 | 4 | 3 | > P95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| HIV | 39 | 36 | S | 40 | S | 11 | S | 80 | 89 | 56 | < P05 | 94 | 56 | 100 | |

| 10 | 8 | 7 | 5 | > P95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| HV | 39 | 16 | S | 31 | S | 4 | S | 36 | 69 | 21 | < P05 | 100 | 80 | 100 | |

| 9 | 8 | 12 | 2 | > P95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

Analysis of Variance for all hair parameters and age in patients

| Density [Table 1] | Growth [Table 3] | Productivity (A6 %, LHGR, CIHG, TTCC [Table 5]) | SCS [Table 7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanos (<20μm) | 20μm | 30μm | 40μm | 50μm | ≥ 60μm | Total | Anagen≥20 μm | Telogen≥20μm | Anagen≥30 μm | Telogen≥30 μm | Anagen≥ 40μm | Telogen≥ 40μm | Anagen≥ 50μm | Telogen≥ 50μm | Exogen tot | A6% 20-30 μm | A6% 40-50 μm | A6% ≥ 60 μm | LHGR 20-30 μm | LHGR 40-50 μm | LHGR ≥ 60μm | CIHG 20-30 μm | CIHG 40-50 μm | CIHG ≥ 60μm | Area % | TTCC Days | Vertex | Crown | Mid-Parting | |||

| ANOVA | 2-way | age groups | (*) | (*) | (*) | ** | ** | (*) | * | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ** | ** | * | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | (*) | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||||||||||

| interaction age-group | (*) | * | * | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Female | this group | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LI | vs | LII | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |||||||||||||

| vs | LIII | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | ||||||||||||||

| vs | NoP | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| vs | Other | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LII | vs | LIII | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |||||||||||||||||||||

| vs | NoP | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | ||||||||||||||||

| vs | Other | S | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LIII | vs | NoP | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | ||||||||||||||

| vs | Other | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |||||||||||||||||||

| NoP | vs | Other | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discrimination power | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 8 | ||

| TOP ≥7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANOVA | 2-way | age groups | (*) | ** | (*) | ** | (*) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | *** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | (*) | * | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |||||||||||||

| interaction age-group | * | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | this group | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H I - H II | vs | H III | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | ||||||||||||||

| vs | H IV-V | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | ||||||||||||

| H III | vs | H IV-H V | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | ||||||||||||||||||

| Discrimination power | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||

| TOP ≥2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tables 1, 3, 5 and the 3 first columns in Table 7 with absolute values are systematically followed by the display of the same parameters with percentiles [Tables 2, 4, 6, and 3 last columns in Table 7] i.e., percentages of patients below the P05 or exceeding the P95 value of gender-matched controls.

Accordingly, the most synthetic parameter “Time To Complete Coverage” (TTCC; day) was tested by simple correlation-regression with midline SCS, i.e., the most powerful SCS.

Finally, Table 8 is a global display of statistics appearing in Tables 1, 3, 5 and 7 in regard with ageing and highlights the best discriminating hair parameters. The effect of ageing was tested with the two-way ANOVA on patients only. As some categories did not contain a sufficient number of subjects within the allocated age ranges, patients with nearest severity constituted one subgroup (e.g., HI-HII). The summary table reports clearly on the global statistically significant differences vs. controls when P values were P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, symbolised, respectively, with *, ** and ***. When P = 0.05, we added (*). Once global significance of differences was established, the Bonferroni/Dunn test was used to evaluate statistically significant differences between each clinical category vs. gender-matched healthy controls, as symbolised by “S”.

Longitudinal studies

Triplicate evaluations of SCS were tested for changes over the six-month period of observation with Student’s t test.

Observations on acute changes of hair productivity and with SCS initiated by drug treatment[13] are limited to description. Findings are commented in terms of consistency or lack of correlation between methods and are presented along with clinical relevance and interpretation of the findings.

The preliminary validation of training for SCS and regression-correlation between the original investigator and independent external observers is not discussed in the present report.

Results

The present study involved 414 subjects complaining of hair loss. Once questionnaires for self-evaluation were delivered, all were examined by the same investigator between 2006 and 2019 before completion of technological procedures described herein.

Analytical and global data can be found in the tables. After subdividing data for consistent type of parameters, in the two genders separately, clusters were evaluated separately and are presented accordingly in a series of tables reporting descriptive statistics of static and dynamic values.

Hair parameters in gender-matched healthy controls are shown in comparison with the various groups of patients complaining of hair loss.

Absolute data appear in a series of tables with odd roman numbers [Tables 1, 3 and 5]. Tables with even numbers [Tables 2, 4 and 6] display the same parameters with the range of normal values (P05 and P95 percentiles in healthy controls) along with the proportion of patients’ data outside these normal limits.

Selected graphic displays of static or dynamic functional data are shown and commented in this paper. Whenever necessary or crucial, correlation or lack of correlation between the global and analytical data is presented.

The general trend pointed towards decreased follicular performance with disease severity; we found that healthy controls - especially females - had high numbers of rather thin hair (diameter groups 20-30 µm and 40-50 µm). These healthy fine hairs maintained good productivity.

While anagen parameters were usually decreased in patients, the absolute values of density of telogen and exogen hair were not remarkable except in the most severe conditions.

We present the results of cross-sectional studies on analytic static and dynamic parameters first, followed by age-related aspects and more global perception by clinical observers. We end with longitudinal studies and correlate global perception with scalp hair follicle productivity and suggest novel approaches capable of tracing performance of hair follicular units.

Cross-sectional studies

Static parameters: hair counts

The usual static data such as density appear in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Hair densities in female and male patients with pattern hair loss (PHL). Hair density (n/cm2) allows a rather static description of a dynamic process in PHL. Hair counts were established with our phototrichogram in PHL, respectively, Ludwig (females, LI-LIII) and Hamilton (males, HI-HV). Patients were ranked by decreasing THD (large open circles), and all differences of THD within gender were statistically significantly different. Accordingly, the rank was HI, LI, HII, HIII, LII, HIV/HV and LIII. where the gradual reduction in THD reflects the severest chronic regression. We draw attention to the fact that LII and HIV/HV show equal total hair density. The gradual decrease in hair density after splitting into a range of diameter categories illustrates that the main contributor to decreased total hair density is terminal hair (open squares). While intermediate (open green triangles) appears quite dense in HI males, hair thinning (open red small circles) does not compensate hair density with increasing severity of PHL. This most likely reflects extended empty follicles between cycles. Finally, in the most severely affected patients (LII, HIV-HV or LIII), the hair fibre densities spread almost equally into the three thickness categories: terminal, intermediate and vellus-like hairs. The average density of nanohair (< 20 µm; small plain blue diamonds) in PHL always exceeded the 95th percentile value of healthy controls independently of gender or severity, as shown by the dotted blue line at the bottom. The density of nanohair appears as a new sensitive and specific diagnostic parameter in patients complaining of hair loss. As far as PHL is concerned (with the notable exception of HI), it is statistically significantly increased in all patient groups either female or male [Tables 1 and 2]. THD: total hair density.

The detailed statistically significant differences between patients and controls appear in Table 1 for hair counts and Table 2 for data distribution in patients vs. controls (5th and 95th percentiles).

With the notable exception of the “No-pattern” subgroup where increased terminal hair densities were found as compared with controls, female patients collectively show decreased intermediate-terminal hair with an almost systematic and statistically significantly rise in nanohair density. While average density of thinnest hair in female patients was increased (nanohair), other thinning hair such as 20 µm appeared almost unaffected and the 30 µm and 40 µm and total hair densities were equal or even lower in patients. As compared with gender-matched controls, the increase in nanohair in male patients with moderately severe patterning mirrored the decrease of terminal hair (≥ 60 µm) and total hair densities.

The distribution of data is important for clinicians to consider, and it is of note that no patient had less nanohair as compared with their gender-matched control group while 50% or more showed higher counts of nanohair than controls.

Amazingly, a kind of mirror image is found in total hair density (last column) where lower densities were found in the majority of patients vs. controls. The percentages of patients also give a hint to clinicians in terms of parameters that might be useful discriminants. Although static in essence, calibrated hair counts already reflects dynamic that reflect shortened anagen duration and prolonged emptiness after exogen release, as shown in Table 3.

Dynamic parameters

Growing and resting hair counts

Tables 3 and 4 show dynamic parameters such as absolute densities of anagen and telogen. Anagen but not telogen densities were statistically significantly reduced in patients as compared with gender-matched controls.

In females, we found a notable exception to this in the “No-pattern” group with normal anagen hair in the thickest intermediate hair category (≥ 50 µm).

Even when telogen density showed globally significant differences, the spread of values was such that no subgroup differed statistically significantly from controls.

Similarly, exogen hair density was found to be increased vs. controls only in the most severely affected patients.

In males, the variations appeared similar to those observed in females with densities of growing or anagen much more impacted than telogen hair densities.

Table 4 confirms that, independently from gender, terminal anagen density (≥ 50 µm) regresses substantially in the majority of patients with PHL (around 75% of females from severity LII or of males from HIII).

The normal distribution of terminal hair (anagen and telogen) in the female NoP and LI groups contrasts with lowered anagen per cent when thinner hairs were included (anagen ≥ 20 µm; more subjects below P05 of controls).

This combination reflects regression in terms of growth along with the reduction in hair diameter and contributes to the perceived reduction of the mass of scalp hair.

The comments in FPHL apply generally to MPHL where the regression of follicular dynamics explains the static data and documents shortened anagen and prolonged emptiness after exogen release, all contributing to decreased follicular performances.

The linear growth rate during progression of hair loss warrants a closer view as in any chronic regressive disorders ageing might contribute by itself.

Hair productivity

The details on statistically significant differences between patients and controls are presented in Table 5 (absolute data) and Table 6 (Percentiles) with the more sophisticated and complex computations in the five last columns. The percentage of anagen hair (A6%) was reduced in more severely affected females LII and LIII for the finest hair (20-30 µm and 40-50 µm). In all female patients, the LHGR of intermediate hair with diameters 40-50 µm was significantly reduced vs. controls.

The absolute productivity of thinner and intermediate hair (20-30 µm and 40-50 µm) was lower in all female patient groups as compared with controls. Productivity (CIHG area %/day) of terminal hair in female patients without a clear pattern (Other) and in the less severely affected LI group was almost equal to controls, while it exceeded control values in the No-pattern group. The global productivity (CIHG Tot) was in the normal range for the NoP group while significantly reduced in patients classified as “Other” as well as in the LII and LIII subgroups in correlation with increased time to complete coverage.

In MPHL, there was a shift from decreased productivity of terminal hair towards increased productivity of thinner hair as compared to controls. This compensation was inefficient in terms of global productivity (CIHG Tot) that significantly reduced along with increased severity, i.e., from HII to HV. This matches with an extremely prolonged duration of the time to complete coverage and most likely reflects the gradual involvement of the ROI by the regression process. Independently from gender, over 70% of patients stayed beyond P05 threshold for positive parameters of growth (CIHG Tot) and went beyond P95 for time to complete coverage (female LII, LIII and “Other” and male HIII-HV) all in relation with regression of follicular performances. In addition, when the per cent anagen drops below 60%, which means that the maximum length of the hair produced would probably remain shorter than 3 cm, the contribution to coverage and mass of scalp hair becomes negligible with decreased coverage as displayed in [Table 7]. This hypothesis implies that growth rates would remain constant during hair loss and throughout lifespan. Therefore, we investigated the role of ageing on follicular performance.

The global ANOVA on age found MPHL with higher severity to be significantly older than less affected ones (P = 0.0004). There were no significant age differences in female groups (independently of the presence PHL). While age was generally not a major factor of variation in most parameters, some degree of regression was unravelled, as shown in Figure 5. The detailed results of statistical analysis are displayed in [Table 8]. The follicular productivity or CIHG results from the following operation: number of growing hair per unit area × LHGR × Diameter [area in µm2/(cm2 × 24 h)]. Provided that one exhaustively probes all productive follicular units in the outlined scalp surface, CIHG can easily be converted into scalp covered by hair, i.e., area %/day, before its final translation into TTCC, as shown in the last two columns of Tables 5 and 6. It is clear from the latter that the arithmetic interval between two adjacent clinical categories (i.e., 1) varies widely according to gender and severity. TTCC documents unequal intervals with a few examples: TTCC between LII and LIII (88.79-50.26 = 38.53 days) is almost double the difference between LI and LII (50.26-28.95 = 21.31 days), and similarly HIV and HV (119.9-68.75 = 51.15 days) differs greatly from HIII and HII (44.7-28.11 = 16.59 days). In short, based on classes and independently of gender, an equal difference of one grade in clinical classification would arithmetically mean that 16.59 = 21.31 = 38.53 = 51.15; i.e., if 1 ≠ 1, we practice fancy arithmetic.

Figure 5. Linear growth rates according to hair diameter and gender along with ageing in patients complaining of hair loss. Age is shown on the x-axis (years) and growth rates on the y-axis (LHGR, µm/day; scale from 150-400 µm/day). Female data appear as circles while male data are symbolised by squares. The symbols for genders apply in this figure whatever the diameter of hair fibres category and the same gender-symbols are also used in Figures 8 and 9. The largest plain symbols represent terminal hair (diameter ≥ 60 µm), smaller plain symbols represent thinning intermediate hair (diameter 40 µm) and smaller empty symbols are for the thinnest hair (paler print 30 µm and more contrasted 20 µm). The average LHGR of 50 µm diameter are not shown in this figure as data caused substantial amount of overlap. Detailed statistical values on age interacting with clinical classification on hair dynamics are given in Table 8. The diameter of the hair fibre exerts a major statistically significant influence on the daily growth rate. Whatever the age, the terminal hair clearly grew more quickly than the thinner intermediate hair (larger and smaller plain symbols, respectively) and all miniaturising hair (open symbols). However, with increasing age, the relative difference became gradually less marked. The statistically significant linear regression for the terminal hair vs. age appears, after combination of data for both genders, as shown by the line across the larger plain symbols. The pure effect of ageing cannot be separated from longstanding exposure to the noxious mechanisms responsible for the regression process. LHGR: Linear hair growth rate.

Finally, let us focus again on the SCS data gathered by the clinical observer. SCS appeared, during this cross-sectional study (absolute SCS and its relative per cent to the maximum) together with the percentiles outside the normal limits [Table 7] to perfectly fit with diagnostics in dermatology clinics. On top, it is obvious (last column midline parted hair; < P05) that a high proportion of patients with lowered SCS allowed a clinical observer to quantify objectively a subjective complaint of hair loss.

At least 80% of patients (all groups except females NoP) had an abnormally low SCS value on midline parted hair. When the same was tested exclusively in groups of patients, there were 8/10 possible comparisons in females and 3/3 possible comparisons in males [last columns in Table 8: highlighted fields TOP ≥ 7 in females and TOP ≥ 2 in males]. This means that a global score would not differentiate between female patients between LI and Other or NoP and Other.

This also leads to the observation that SCS on the top of the head with hair parted along the midline is perfectly complementary to the simplest clinical classification. However, quantitative information comes in addition to pattern selection (as some patients have no pattern), a clinical benefit by objective estimation of the patient.

The most global analytical parameter, TTCC (the shorter the better), and the consistent scalp coverage scoring after mid-parting of hair (SCS; the higher the better) nicely fitted clinical classifications. By correlation-regression between the two most representative analytical parameters, we generated an abacus that translates clinical scores into productivity and vice versa.

Before beginning the detailed analysis of observer vs. self-estimation and correlation study between SCS and hair productivity, we present the results obtained with computer graphics. We simulated the degree of difficulty to observe scalp skin through the hair, with the highest difficulty score represented by black (5) to the lightest shown as white (0). The averages and statistically significant differences translated from data in Tables 7 and 8 are shown as a visual chart for top of the head fields before and after midline parting [Figure 6].

Figure 6. Computer simulation of patterns based on scalp coverage scoring (SCS) in patients complaining of hair loss. Figure 6 (left of vertical double bar) shows fields known as top and vertex, frontal and lateral or midline-parted (groups of numbered squares as detailed in earlier section). The sum of SCS in each field mathematically documents coverage and is tested statistically by comparing the SCS in a clinical group vs. a theoretical maximum score. If a field contains nine squares, then 9 × 5, i.e., 45, is the maximum attainable score (100%) while the parted-midline maximum is 4 × 5 = 20 (100%). Intermediate sum of scores would translate relatively speaking into grey shades in this artistic representation. As detailed in Tables 7 and 8 (SCS relative per cent of maximum), there were statistically significant differences in SCS values between patients in these fields. For a clinical correlation, we typically refer the reader to Figure 1 where sum SCS 100% would easily be reached in the top-vertex or lateral-crown fields by the two subjects appearing on the left [Figure 1E; HI]. On the contrary, the 2 probands appearing on the right would be closer to 10%-20% (HIV and HV) with “no difficulty observing scalp skin through the hair”. For females, we refer to clinical images shown in Figure 2. The images in the two top rows clearly illustrate that scalp skin is less easily visible in NoP, LI or Other [analogous to Figure 6A] than in LII [analogous to Figure 6B] or LIII [analogous to Figure 6C]. Of note is that the crown becomes involved in Figure 6C, i.e., in the most severely affected subjects. Comparing density in each paired left and right diagrams in these three panels [Figure 6A-C], it is clear that midline parting displays lighter grey levels. Lower SCS scores mean that combing the hair apart unravels a decreased coverage on the top-vertex on the crown, especially in the most severe cases [Figure 6B and C].

Global approaches: self-estimates of hair loss, clinician’s classifications and SCS.

Before discussing the field of perception, it is worth mentioning that, in our hands, gentle pulling on clean scalp rarely exceeded five hairs (one patient with LIII and one subject with HIV).

This probably reflects a small number of patients facing an unnoticed sudden acceleration phase amidst the more chronic rather slowly regressing disorder or less compliant patients, i.e., no shampoo on the day of clinical visit.

Self-estimates of hair loss

The self-estimated scalp hair status was written down in the questionnaire by the patient during the clinical visits. The scores diverged frequently from the clinical observer, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Self-estimated severity scores by patients complaining of hair loss versus clinician’s estimates of pattern and severity. Female and male patients appear, respectively, in the left and right panels. All patients received the questionnaires and cartoons on their first visit to the clinic. They were not given any assistance during the reporting to be returned at the second visit. This prevents undue interferences between observer and patient evaluations. From the initial 304 females, we retrieved 294 duly completed files. From the initial 110 males, self-scoring documents were lacking for four subjects, thus 106 were retained. The other questionnaires were considered as lost to follow-up. The dermatologist’s classification appears as “DermPattern” in the shaded areas (blue) while the “self minus derm” (red bars) reflect the differences between patient’s self-estimated classification and the clinical severity attributed by the dermatologist. Positive bars indicate overestimation while negative bars indicate underestimation by patients as compared with the dermatologist’s evaluation. In the pool of 294 females who completed the self-administered questionnaire, there is no apparent surface when dermatologist found no pattern (cases on the left side of the vertical bar; no pattern (NoP) scored as 0). The cases on the right side of the vertical bar appear as positive shaded areas (light blue) reaching up to 1, 2 or 3 (scale from -3 to +3; y-axis) for females with a Ludwig pattern rated as LI, LII or LIII, respectively. Only 5% of the pool of 294 females (14 occurrences in total; eight in NoP and six in LI) overestimated their condition and attributed a more severe score. Complete agreement between subjective estimates by females and clinician was recorded in 38% of females while underestimation occurred in 57% of the female patients (167 cases; one grade for 140 subjects and two grades for 27 subjects). Similarly, in males (all pattern hair loss; scale from -5 to +5), only 2.5% overestimated the severity (one HII by two grades and one HIII by one grade), while 85% and 72% of HIV and HV, respectively, underestimated the clinical class attributed by the investigator.

Contrary to the often-held opinion on patients exaggerating the phenomenon of hair loss, we observed the great majority of subjects underestimated the severity.

SCS cross-sectional study correlates with scalp hair productivity

The scalp target for non-invasive functional investigations or ROI was chosen after obtaining agreement of the patient, at a distance from the most severely affected sites, e.g., remote from the epicentre or at the progression edge of the balding process.

With SCS, in the least severe cases, typically in females NoP and LI or males HI and HII, we know that the clinician was unable to quantify hair loss, as illustrated in Figure 7, albeit most patients already showed increased counts of nanohair [as shown in Figure 4 and detailed in Tables 1-8.

The abacus in Figure 8 displays all data from 414 individual patients and 90 controls. For completeness, the dispersion of data around the average is shown separately for females and males in Figure 9. HMI abacus derives follicular performance from clinical rating of the “difficulty to detect scalp skin in between hair”.