Graphene oxide modified electrode enhances electricity generation and heavy metal removal in photosynthetic microalgae microbial fuel cells

Abstract

Improving the power generation performance and pollutant removal of photosynthetic microalgae microbial fuel cells (PMMFCs) is the key to their large-scale application. In this work, microalgae (Chlorella sp. QB-102) were used as a biocatalyst in the cathode, and foam nickel modified by graphene oxide with two degrees of oxidation was used as the electrode. The results showed that the maximum power density of PMMFCs with high oxidation degree graphene oxide modified electrode (NF-GO-H) reached 209.07 mW·m-2, which was 6 times that of PMMFCs with low oxidation degree graphene oxide modified electrode (NF-GO-L), indicating that the use of the NF-GO-H electrode can effectively improve the electrical properties of PMMFCs. Simultaneously, the NF-GO-H electrode can effectively remove Cd(II), with a capacity of 6.039 g·m-2, which is twice that of the NF-GO-L electrode. Moreover, through the synergistic electrochemical action of Chlorella sp. QB-102, a large number of hydroxyl groups can be generated to convert the adsorbed Cd(II) into a more stable Cd(OH)2 precipitate. The results of this work will further expand the application of PMMFCs in power generation and heavy metal removal.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

With the rapid development of industrial production and the continuous expansion of urban construction, heavy metal ion pollution has become a global environmental problem[1]. Cadmium is a typical heavy metal pollutant, widely existing in electroplating, pigment, paint, metallurgy, electronics, and other industries[2,3]. When cadmium enters the environment, it can enter the human body through the food chain and be enriched, mainly accumulating in the liver, kidney, and bone, causing the kidney and other tissues and organs to become diseased[4-6]. A very small amount of cadmium can cause harm to the human body and seriously threaten people’s lives, health, and safety[7]. Cadmium removal processes such as chemical precipitation, ion exchange, membrane separation, electrochemical, adsorption, and others have been extensively utilized, but the potential for secondary pollution and high energy consumption limit the application of these methods[8-10]. Therefore, the study of low energy consumption, high efficiency, and green environmental protection technology for the treatment of cadmium pollution in water is of great significance for realizing the harmonious and healthy development of humans and nature.

Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) are a new type of bio-electrochemical system with low cost, high efficiency, and no secondary pollution, which can simultaneously generate electricity and remove pollutants[11-14]. At present, it has been proven that Cu, Cr, Pb, Cd, Zn, and other heavy metal ions can be used as electron acceptors in MFCs to achieve ion removal, recovery, and continuous electricity production[15-17]. Introducing microalgae into the cathode chamber of MFCs to construct photoautotrophic microalgae microbial fuel cells (PMMFCs) is a new research direction in recent years[18-19]. On the one hand, the microalgae at the cathode can use carbon dioxide in the anode chamber for photosynthesis to produce oxygen, H2O2 and free radicals as electron acceptors, avoiding mechanical aeration, reducing energy consumption, and improving electricity production capacity[20]. On the other hand, the microalgae at the cathode can remove heavy metals through bioadsorption, biomineralization, biotransformation, bioaccumulation, and enhanced electrochemical action[21]. Although PMMFCs technology has been widely studied, how to improve power generation efficiency and heavy metal removal rate is still the focus of current research[22,23].

There are many factors affecting the performance of MFCs, including microbial species, cultivation temperature, solution pH, substrate concentration, electrode material, the distance between electrodes and added electrolyte, etc.[24]. Among them, electrode material is one of the key technologies affecting the output power of microbial fuel cells[25]. The anode of PMMFCs is the growth and activity area of the electricity-producing microorganism, so it needs to have high biocompatibility, high specific surface area, and high conductivity to enhance the extracellular electron transfer (EET) between the electricity-producing microorganism and the electrodes[19,26]. At the same time, due to long-term exposure to a complex component of electrolyte, the anode material is also required to have durable corrosion resistance and chemical stability[26]. Unlike the anode material, the cathode material of PMMFCs itself needs to have high electrochemical catalytic capacity, so that the electrons transmitted from the anode can react with oxygen and protons to generate water[27]. Graphene oxide (GO) is a quasi-two-dimensional spatial structure and contains a large number of oxygen-containing functional groups on the sheet, so it has excellent hydrophilicity, good mechanical stability, high biocompatibility electrocatalytic performance and large specific surface area (theoretical value of 2,630 m2·g-1), making it the most potential candidate electrode material[28,29]. Some scholars have shown that the use of a GO-modified cathode or anode can effectively improve the power generation effect of PMMFCs[30,31]. Interestingly, GO with different oxidation degrees is significantly different in size, defect number and content of oxygen-containing functional group, which directly affects the biocompatibility, conductivity and catalytic performance of GO[32,33]. However, so far, no one has studied the effect of a GO-modified electrode with a different degree of peroxide on PMMFC power generation. At the same time, there are few studies on the simultaneous treatment of heavy metal wastewater and power generation using GO-modified electrodes, and the removal mechanism of heavy metals is still unclear and needs further exploration.

In this study, GO with different oxidation degrees was prepared using abundant natural graphite ore in China, and the prepared GO was combined with nickel foam as the cathode and anode of the PMMFCs to explore its effect on electricity production. At the same time, the efficiency of Cd(II) removal by PMMFCs was monitored, and the mechanism of Cd(II) removal by PMMFCs was studied by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) methods. The results of this work will further expand the knowledge of the use of PMMFCs and contribute to the understanding of how algal cells can be used in the most cost-effective way for heavy metal removal from water.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of electrode

GO was prepared by an improved Hummer method[34]. The specific operation steps are as follows: Add 150 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid into a 500 mL conical flask, create an ice bath, and set the speed of the magnetic stirrer to 350 rpm. Then add 3 g graphite and 1.5 g NaNO3 and stir for 10 min. Then slowly add

400 mg of GO powder was mixed with 100 mL of deionized water. Then shear the mixture with a FLUKO high-shear homogenizer (Germany) at 10,000 rpm for 4 min. The GO was further exfoliated ultrasonically with a Cole-Parmer ultrasonic processor (CP505, American) at the power of 300 W for 20 min. Then the colloidal suspension was centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 3 min. The supernatant was graphene oxide

Nickel foams (3 cm × 4 cm) were immersed in HCl, ethanol, and deionized water successively, and the soaking time in each solution was 30 min. Then they were vacuum dried for 3 h at 40 °C for pretreatment. For electrode preparation, they were immersed in a GO solution (4 mg·mL-1) in vacuum at 40 °C for 2 h. By measuring the content of residual graphene oxide in the solution, it is calculated that the graphene oxide loaded on foam nickel is about 0.32 mg·cm-2. Then the nickel foams were immersed in hydrazine hydrate

Characterization of electrode

XPS measurements of electrodes were analyzed by an X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (ESCALAB 250Xi, China). The oxidation degree of GO on the electrode surface was analyzed by a CHNS/O elemental analyzer (Vario EL cube, Ger many). The defects of GO on the electrode surface were evaluated by Raman spectroscopy (InVia, England).

The morphology images of electrodes were obtained by field emission scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi 4800, Japan). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) samples need to be pretreated. The specific pretreatment steps are to first wash the samples with 0.01 mol/L phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by soaking overnight with glutaraldehyde (2.5%, pH = 6.8) in the refrigerator. Then it is dehydrated with 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100% ethanol in turn, and finally, vacuum dried at room temperature for the night.

PMMFCs construction and operation

The activated sludge was collected from the anaerobic pool in the Tangxunhu sewage treatment plant in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. It is anaerobically cultivated in the cultivation medium (12 g·L-1 CH3COONa, 133.725 mg·L-1 NH4Cl, 14.046 mg·L-1 K2HPO4, 1.6 mg·L-1 CoCl2·6H2O, 5 mg·L-1 FeSO4·7H2O,

Chlorella sp. QB-102 was isolated from the lead - zinc tailings at Qibao Mountain, Jiangxi Province, China, and cultivated in a light incubator (GXZ, China) with BG11 medium [40 mg·L-1 K2HPO4,

The reactor used in this experiment is a traditional two-chamber microbial fuel cell, which is made of organic glass. The volumes of the anode chamber and the cathode chamber are both 250 mL. The conical flask, centrifuge tube, electrode, etc. contacted in the test process need to undergo high-temperature sterilization and ultraviolet sterilization, and then carry out microbial inoculation on the ultra-clean workbench. The anode electrolyte was activated sludge suspension with a settlement height of 2 cm for 1 h. The cathode electrolyte was Chlorella sp. QB-102 suspension with an absorbance of 2 at a wavelength of 680 nm. The anode and cathode were separated by a proton exchange membrane (PEM). Place the reactor in the light incubator and run it at 25 °C with a 14/10 h light-dark cycle under 200 μmol/(proton·m2·s) artificial light. Connect the anode and cathode electrode pieces via a 1 mm thick titanium wire to an external resistance of 1,000 Ω and measure the voltage with a multimeter (UT171B, China). After the voltage is stable for 2 days, open the circuit overnight and measure the power generation performance by changing the external resistance value.

Monitoring and analysis of the PMMFCs

The current density was calculated by the equation I = V / (R × A), and the power density was calculated by the equation P = V2∕ (R × A), where V was the voltage value (V), R was the external resistor (Ω), and A was the surface area of the electrode (m2).

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of electrodes were both conducted by an electrochemical workstation (VersaSTAT 4, America). The interference voltage and frequency range were set to 5 mV and 100 kHz - 10 mHz, respectively. The scanning rate was set to

Analysis of microbial community structure

The community diversity structure of anode sludge from a microbial fuel cell was analyzed by high throughput pyrophosphate sequencing and clone libraries. The following is the precise measurement method: First, take 1 mL of biomass from the anode activated sludge and put it into a 5 mL centrifuge tube, wash it with one time of phosphate buffer, and then use a high-speed freezing centrifuge to collect its precipitation at 16,000 rpm to obtain DNA, and then use PCR technology to amplify the 16S rRNA gene.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of NF-GO-L and NF-GO-H

Physical and chemical characterization of electrodes

The content of C, H, and O elements in GO on the electrode surface was determined by an elemental analyzer. As shown in Figure 1A, the C/O of NF-GO-L (2.682) is greater than that of NF-GO-H (1.131), indicating that the oxidation degree of NF-GO-H is greater than that of NF-GO-L. The reduction experiment decreased the oxidation degree of GO.

Figure 1. Material characterization of NF-GO-L and NF-GO-H electrodes, including (A) C/H/O element content; (B) Raman spectroscopy; (C) C1s of NF-GO-L; (D) C1s of NF-GO-H.

The Raman diagram of GO on the electrode surface is shown in Figure 1B. The G peaks of GO caused by stretching of the sp2 atomic in the carbon ring or chain are located at 1,601 cm-1 and 1,602 cm-1, respectively[35]. The D Peak located at 1,351 cm-1 (NF-GO-H) and 1,335 cm-1 (NF-GO-L) is produced by the respiration vibration mode of sp3 atomic in carbon ring[35]. D peak reflects defects caused by vacancy, grain boundary, and amorphous carbon species. ID/IG reflects the disorder degree of crystal structure[36]. In addition, 2D peaks were derived from the second diphonon mode at 2,713 cm-1 and 2,711 cm-1, respectively. The D + G peaks appeared near 2,939 cm-1 and 2,934 cm-1; ID+G/I2D could be used to assess the surface defect concentration of graphene.

The relevant data are listed in Table 1. The ID/IG of NF-GO-L is greater than that of NF-GO-H, indicating that the disorder of NF-GO-L is greater. The ID+G/I2D of NF-GO-L is greater than that of NF-GO-H, indicating that the defect concentration of NF-GO-L is greater. In conclusion, the disorder and defect concentration of NF-GO-H were relatively small, while the disorder and defect concentration of NF-GO-L were relatively large. As the defect degree increases, so will the electrical conductivity and electron mobility of GO[37].

Parameters of Raman spectra for graphene oxide on electrodes

| Sample | D peak (cm-1) | G peak (cm-1) | 2D (cm-1) | D + G (cm-1) | ID/IG | I(D+G)/I2D |

| NF-GO-L | 1,335 | 1,602 | 2,711 | 2,934 | 1.127 | 1.148 |

| NF-GO-H | 1,351 | 1,601 | 2,713 | 2,939 | 0.956 | 0.781 |

The GO on the electrode surface was tested by an X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, and the results of the C1s spectrum are shown in Figure 1C and D. The C1s spectrum of NF-GO-H is divided into three peaks at 284.18 mV, 286.18 mV and 288.28 mV, which correspond to the three groups C-C/C=C, C-O, and O-C=O[38]. The three groups of NF-GO-L (C-C/C=C, C-O, and O-C=O) are at 284.38 mV, 285.68 mV and 288.48 mV, respectively[38]. The relative area ratios of the three groups are listed in Table 2. It can be found that the total relative area ratios of the oxygen-containing functional groups (C-O, O-C=O) of NF-GO-H are greater than those of electrode NF-GO-L. It indicated that the oxidation degree of NF-GO-H is greater than that of NF-GO-L, which is consistent with elemental analysis results.

Functional groups composition of graphene oxide on electrodes obtained from X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (at %)

| Sample | C-C/C=C | C-O | O-C=O | Oxygen-containing functional groups |

| NF-GO-L | 71.96 | 18.60 | 9.44 | 28.04 |

| NF-GO-H | 30.65 | 64.41 | 4.94 | 69.35 |

Electrochemical characterization of electrodes

The CV curve of PMMFCs was measured by a two-electrode electrochemical workstation. The results are shown in Figure 2A. There was no redox peak on the CV curves of the two kinds of PMMFCs, indicating that no redox reaction occurred on the electrode surface[39]. The closed area of the CV curve represents the amount of charge moved in and out during the redox process on electrode surface[40]. The CV curve integral area of two groups’ PMMFCs with NF-GO-H and NF-GO-L was 0.14 and 0.12, respectively, and the difference was not large. The conductivity of electrode NF-GO-H was slightly higher than that of electrode NF-GO-L. The conductivity of graphene oxide is known to be inferior. The conductivity of electrodes with a high degree of oxidation is greater than the conductivity of electrodes with a low degree of oxidation, which is consistent with the results of the Raman test, mainly because GO with a low degree of oxidation contains more defects.

Figure 2. Electrochemical characterization of NF-GO-L and NF-GO-H electrodes, including (A) Cyclic voltagrams and (B) Nyquist plots.

Figure 2B is the impedance diagram of PMMFCs with two electrodes. The impedance diagram is mainly composed of two parts: a semicircle in the high-frequency region and a straight line in the mid- and low-frequency regions. The longer the linear part of the low-frequency region, the easier and faster electron transfers from the electrode’s surface to its interior. The straight part of the electrode is approximately 45° with the horizontal coordinate in the low and medium frequency region. It is the special property of the porous electrode, indicating that the transfer of charge on the electrode is controlled by diffusion. In the high-frequency region, the impedance curve is a semicircle, where the diameter of the semicircle represents the electrode impedance, which is mainly caused by the ohmic polarization of electrons through the membrane. In other words, the shorter the diameter of the semicircle, the smaller the impedance of the membrane, and the faster the redox reaction rate on the electrode surface[41]. After that, the impedance diagram was fitted by Zview software, and the fitted circuit is shown in Figure 2B. The resistance of PMMFCs with NF-GO-H is 106.4 Ω. The resistance of PMMFC with NF-GO-L is 153.9 Ω. It can be seen from the above that the resistance of PMMFCs with NF-GO-H is smaller.

Power production

Polarization curve and power density curve

The polarization curve and power density curve of PMMFCs with different electrodes are shown in Figure 3. The voltage on the polarization curve decreases as the current density increases. The linear slope reflects the internal resistance of PMMFCs[42]. The linear slope of polarization curves of PMMFCs with NF-GO-L is greater than that with NF-GO-H, indicating that the internal resistance of PMMFCs with NF-GO-L is greater than that with NF-GO-H, which is consistent with the test data of electrochemical impedance. PMMFCs with NF-GO-H access the highest power density of 209.07 mW·m-2 with an external resistance of 200 Ω, while PMMFCs with NF-GO-L access the highest power density of 32.90 mW·m-2 with an external resistance of 2,000 Ω. The power density increased with the GO oxidation degree on the electrode surface. When the maximum power density is obtained, the external resistance can be approximately equal to the internal resistance of PMMFCs, indicating that the internal resistance of PMMFCs with NF-GO-L is greater than that with NF-GO-H, which is consistent with the polarization curve and chemical impedance data.

Figure 3. Polarization curves and power density curves of photosynthetic microalgae microbial fuel cells (PMMFCs) with NF-GO-L and NF-GO-H.

Table 3 lists the power generation capacity of different PMMFCs. As can be seen, the power generation capacity of PMMFCs is generally low. PMMFCs modified with GO electrode with a fresh oxidation degree had a higher power density in this experiment, indicating that electrode modified with GO with a high oxidation degree is an effective way to improve power density.

Comparison of power densities in this study with other reported data

| Microalgae types | Anode | Cathode | Power density (mW·m-2) | Refs. |

| Chlorella sp. QB-102 | NF-GO-H | NF-GO-H | 209.07 | This study |

| Scenedismus obliquus | Carbon paper | CFBC | 30 | [43] |

| Chlorella sorokiniana | Carbon fiber brush | Iron plate | 71.3 - 83.4 | [44] |

| vulgaris | Graphite plate | Graphite plate | 34.2 ± 10.0 | [45] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | stainless steel mesh | Stainless steel mesh | 126 | [46] |

| S. platensis | Gold mesh | Carbon cloth | 10 | [47] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Graphite plate | Platinum- Graphite plate | 62.7 | [48] |

Mechanism of electricity production

The SEM image of the PMMFCs electrode after testing is shown in Figure 4. As can be seen from Figs. 4a and 4c, Chlorella sp. QB-102 is spherical with a diameter of 1-2 μm. The attachment density of Chlorella sp. QB-102 on the NF-GO-H cathode was higher than that on the NF-GO-L cathode. The more Chlorella sp. QB-102 attached to the cathode, the more dissolved oxygen will be produced near the electrode, which can timely consume the electrons transferred from the anode, which may be one of the reasons for the good electrical properties of PMMFCs with the NF-GO-H electrode. As can be seen from Figure 4B and D, rod-shaped bacteria were attached to the surface of the NF-GO-H anode, while no obvious microorganisms were present on the surface of the NF-GO-L anode, which may be due to the physical damage and oxidative stress of bacteria and algae caused by the GO defect with a low degree of oxidation[49,50]. The electrogenic microorganisms attached to the anode are conducive to the EET process, which may be another reason for the good electrical properties of PMMFCs with NF-GO-H electrodes.

Figure 4. (A and B) SEM image of cathode (left) and anode (right) of PMMFCs with NF-GO-H electrode; (C and D) SEM image of cathode (left) and anode (right) of PMMFCs with NF-GO-L electrode. PMMFCs: Photosynthetic microalgae microbial fuel cells; SEM: scanning electron microscope.

The microbial community distribution of anode activated sludge at different operating times is shown in Figure 5. It can be seen that the bacteria on the anodes of NF-GO-H and NF-GO-L are Proteobacteria, Bacteroides, Actinobacteria, and Firmicute. Among the four groups of bacteria, the Proteobacteria have the largest number, and their proportion gradually increases with the culturing time, indicating that they are the dominant bacterial species. According to the literature, in the process of microbial fuel cell power generation, the content of Proteobacteria directly affects the amount of electricity generated[22]. The number of Proteobacteria in the anode added with NF-GO-H was significantly higher than that of the anode added with NF-GO-L, indicating that the anode of PMMFCs added with NF-GO-H had a stronger power generation intensity, which was consistent with the results in Figure 3, proving that the highly oxidized graphene oxide was more conducive to the power generation of PMMFCs.

Removal of Cd(II) from the cathode chamber

Adsorption kinetics of Cd(II)

The same concentration flow drop adding method was used for Cd(II) adsorption by microalgae cathode. The main purpose of this test is to explore the continuous removal effect of PMMFCs connected with different electrodes on cadmium ions. In real life, the concentration of cadmium ions in water generally exceeds the standard by dozens to hundreds of times. Therefore, an intermediate concentration of 1 mg·L-1 was selected. Figure 6A shows the adsorption kinetics test results of the two groups of PMMFCs when cadmium ions were added for the first time. Obviously, the adsorption reaction happens very quickly. Among them, PMMFCs connected to the NF-GO-H electrode reached adsorption equilibrium within

Mechanism of Cd(II) removal

Figure 7 shows the FT-IR changes of the PMMFC cathode before and after cadmium ion adsorption. The absorption peak in the high-frequency region around 3,300 cm-1 is caused by the stretching vibration of -OH in water molecules. The absorption peak between 1,543 and 1,546 cm-1 is the N-H stretching vibration peak in the amide II band. The absorption peak near 1,400 cm-1 is caused by the in-plane stretching vibration of O-H. The absorption peak located between 1,241 and 1,242 cm-1 is related to the P = O stretching vibration in nucleic acid and phosphorylated protein. The absorption peak near 1,060 cm-1 is the stretching vibration peak of C-OH[51]. By comparing the changes in functional groups before and after the test, the absorption peak -OH located near 3,300 cm-1 in the high-frequency region shifted after the adsorption test, indicating that the hydroxyl functional group may be involved in the adsorption reaction.

Figure 7. FT-IR of cathode of PMMFCs before and after Cd(II) adsorption. FT-IR: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy; PMMFCs: photosynthetic microalgae microbial fuel cells.

Figure 8 shows the SEM-EDS image of the cathode electrode after the adsorption test. In the measurement area, cadmium ions were uniformly distributed on the electrode surface, indicating that cadmium ions were indeed adsorbed on the electrode surface. By comparing the left and right pictures, it can be seen that a layer of cadmium ions is also attached to the place where the Chlorella sp. QB-102 are attached, indicating that the Chlorella sp. QB-102 also participate in the adsorption reaction.

Figure 8. (A and B) SEM-EDS image of cathode electrode of PMMFCs with NF-GO-L after adsorption experiment; (C and D) SEM-EDS image of cathode electrode of PMMFCs with NF-GO-H after adsorption experiment. PMMFCs: Photosynthetic microalgae microbial fuel cells; SEM-EDS: scanning electron microscope - Energy dispersive spectrometer.

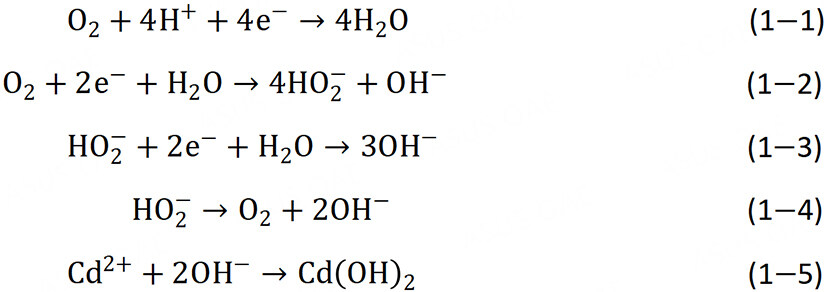

Figure 9 is the X-ray photoelectron spectrum (XPS) of the cadmium element in the cathode electrode sheet of PMMFCs after adsorption. The Cd3d peak can be divided into two groups of symmetric peaks, which are the Cd3d5/2 sub-peak with a binding energy of 405.10 eV (405.15 eV) and the Cd3d3/2 sub-peak with a binding energy of 411.75 eV (412.05 eV)[52,53]. Through a literature review, it can be seen that the substances corresponding to the peaks of these two components are cadmium hydroxide, and the difference in binding energy is caused by the change in the surrounding chemical environment[22]. This indicates that in addition to cadmium hydroxide on the electrode surface, there is also cadmium hydroxide on the surface of Chlorella sp. QB-102 on the electrode, which further confirms the existence of cadmium adsorption by Chlorella sp. QB-102. The formation of cadmium hydroxide on the electrode surface mainly depends on the hydroxide ion produced by the oxygen reduction reaction. There are two main ways of oxygen reduction in the cathode: the four-electron way [Equation 1-1] and the two-electron way [Equation 1-2], in which the by-product of the two-electron way, HO2-, will be reduced by the way [Equation 1-3] or decomposed by the way [Equation 1-4][54,55]. Therefore, the mechanism of Cd(II) removal by PMMFCs is shown in Figure 10. Firstly, Cd(II) is adsorbed on the surface of the Chlorella sp. QB-102 and electrode, and then hydroxyl is continuously generated at the cathode through continuous power generation of the anode, so that the adsorbed cadmium ion is converted into Cd(OH)2 precipitation [Equation 1-5].

Figure 9. XPS of cathode of PMMFCs before and after Cd(II) adsorption. PMMFCs: photosynthetic microalgae microbial fuel cells; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectrum.

CONCLUSION

In summary, two kinds of GO with different degrees of oxidation were prepared from natural graphite and then immobilized on nickel foams as electrodes of PMMFCs, and their effects on the electrical properties and the continuous removal of cadmium ions in PMMFCs were investigated. The results show that GO with a high oxidation degree has better biocompatibility, which is conducive to the adhesion of microorganisms and enhances the effect of electricity production. The maximum power density of PMMFCs connected with the NF-GO-H electrode (209.07 mW·m-2) is about 6 times higher than that of PMMFCs connected with the NF-GO-L electrode (32.90 mW·m-2). In addition, the saturated adsorption capacity (6.039 g·m-2) of cadmium ions by PMMFCs connected to the NF-GO-H electrode is about twice that of PMMFCs connected to the NF-GO-L electrode (3.198 g·m-2). It can be seen that the improvement in electricity generation performance can further improve the effect of continuous removal of cadmium ions by microalgae biological cathode catalyst.

DECLARATIONS

AcknowledgmentThe financial support for this research from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 52074203) is gratefully acknowledged.

Authors contributionsConceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing - original draft: Zhang Z

Visualization: Zhang Y

Writing - review & editing: Garcia-Meza JV

Supervision: Xia L

Financial support and sponsorshipThis study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 51604207).

Availability of data and materialsThe corresponding author will provide the datasets used or analyzed during the current work upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of interestThere are no financial or non-financial interests to disclose for the authors.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2023.

REFERENCES

1. Li FJ, Yang HW, Ayyamperumal R, Liu Y. Pollution, sources, and human health risk assessment of heavy metals in urban areas around industrialization and urbanization-Northwest China. Chemosphere 2022;308:136396.

2. Kumar V, Dwivedi S, Oh S. A review on microbial-integrated techniques as promising cleaner option for removal of chromium, cadmium and lead from industrial wastewater. J Water Process Eng 2022;47:102727.

3. Xu L, Dai H, Skuza L, et al. Integrated survey on the heavy metal distribution, sources and risk assessment of soil in a commonly developed industrial area. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2022;236:113462.

4. Yan J, Zhang H, Niu J, et al. Effects of lead and cadmium co-exposure on liver function in residents near a mining and smelting area in northwestern China. Environ Geochem Health 2022;44:4173-89.

5. Akerstrom M, Barregard L, Lundh T, Sallsten G. The relationship between cadmium in kidney and cadmium in urine and blood in an environmentally exposed population. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2013;268:286-93.

6. Browar AW, Leavitt LL, Prozialeck WC, Edwards JR. Levels of cadmium in human mandibular bone. Toxics 2019;7:31.

7. Liu Q, Zhang R, Wang X, et al. Effects of sub-chronic, low-dose cadmium exposure on kidney damage and potential mechanisms. Ann Transl Med 2019;7:177.

8. Wu J, Wang T, Wang J, Zhang Y, Pan WP. A novel modified method for the efficient removal of Pb and Cd from wastewater by biochar: enhanced the ion exchange and precipitation capacity. Sci Total Environ 2021;754:142150.

9. Jin W, Fu Y, Hu M, Wang S, Liu Z. Highly efficient SnS-decorated Bi2O3 nanosheets for simultaneous electrochemical detection and removal of Cd(II) and Pb(II). J Electroanal Chem 2020;856:113744.

10. Çifci C, Şanlı O. Poly(vinyl pyrrolidone)-enhanced crossflow filtration of Fe(III), Cu(II) and Cd(II) ions using alginic acid/cellulose composite membranes. Desalination Water Treat 2011;29:87-95.

11. Munoz-Cupa C, Hu Y, Xu C, Bassi A. An overview of microbial fuel cell usage in wastewater treatment, resource recovery and energy production. Sci Total Environ 2021;754:142429.

12. Chen J, Yang J, Tian J, et al. A pathway for promoting bioelectrochemical performance of microbial fuel cell by synthesizing graphite carbon nitride doped on single atom catalyst copper as cathode catalyst. Bioresour Technol 2023;372:128677.

13. Liu H, Qin S, Li A, et al. Bioelectrochemical systems for enhanced nitrogen removal with minimal greenhouse gas emission from carbon-deficient wastewater: a review. Sci Total Environ 2023;859:160183.

14. Wang S, Jiang J, Zhao Q, Wei L, Wang K. Investigation of electrochemical properties, leachate purification, organic matter characteristics, and microbial diversity in a sludge treatment wetland- microbial fuel cell. Sci Total Environ 2023;862:160799.

15. Kaushik A, Singh A. Metal removal and recovery using bioelectrochemical technology: The major determinants and opportunities for synchronic wastewater treatment and energy production. J Environ Manage 2020;270:110826.

16. Zhu H, Hu X, Zha Z, et al. Long-time enrofloxacin processing with microbial fuel cells and the influence of coexisting heavy metals (Cu and Zn). J Environ Chem Eng 2022;10:107965.

17. Daud NNM, Ahmad A, Yaqoob AA, Ibrahim MNM. Application of rotten rice as a substrate for bacterial species to generate energy and the removal of toxic metals from wastewater through microbial fuel cells. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2021;28:62816-27.

18. Saba B, Christy AD, Yu Z, Co AC. Sustainable power generation from bacterio-algal microbial fuel cells (MFCs): an overview. Renew Sust Energ Rev 2017;73:75-84.

19. Reddy C, Nguyen HTH, Noori MT, Min B. Potential applications of algae in the cathode of microbial fuel cells for enhanced electricity generation with simultaneous nutrient removal and algae biorefinery: current status and future perspectives. Bioresour Technol 2019;292:122010.

20. Armoza-Zvuloni R, Shaked Y. Release of hydrogen peroxide and antioxidants by the coral Stylophora pistillata to its external milieu. Biogeosciences 2014;11:4587-98.

21. Znad H, Awual MR, Martini S. The utilization of algae and seaweed biomass for bioremediation of heavy metal-contaminated wastewater. Molecules 2022;27:1275.

22. Zhang Y, He Q, Xia L, Li Y, Song S. Algae cathode microbial fuel cells for cadmium removal with simultaneous electricity production using nickel foam/graphene electrode. Biochem Eng J 2018;138:179-87.

23. Yang Z, Li J, Chen F, et al. Bioelectrochemical process for simultaneous removal of copper, ammonium and organic matter using an algae-assisted triple-chamber microbial fuel cell. Sci Total Environ 2021;798:149327.

24. Tang RCO, Jang J, Lan T, et al. Review on design factors of microbial fuel cells using Buckingham’s Pi Theorem. Renew Sust Energ Rev 2020;130:109878.

25. Cai T, Meng L, Chen G, et al. Application of advanced anodes in microbial fuel cells for power generation: a review. Chemosphere 2020;248:125985.

26. Mohan S, Velvizhi G, Annie Modestra J, Srikanth S. Microbial fuel cell: critical factors regulating bio-catalyzed electrochemical process and recent advancements. Renew Sust Energ Rev 2014;40:779-97.

27. Noori MT, Ezugwu CI, Wang Y, Min B. Robust bimetallic metal-organic framework cathode catalyst to boost oxygen reduction reaction in microbial fuel cell. J Power Sources 2022;547:231947.

28. Peng W, Li H, Liu Y, Song S. A review on heavy metal ions adsorption from water by graphene oxide and its composites. J Mol Liq 2017;230:496-504.

29. Kuila T, Mishra AK, Khanra P, Kim NH, Lee JH. Recent advances in the efficient reduction of graphene oxide and its application as energy storage electrode materials. Nanoscale 2013;5:52-71.

30. Lin T, Ding W, Sun L, Wang L, Liu C, Song H. Engineered Shewanella oneidensis-reduced graphene oxide biohybrid with enhanced biosynthesis and transport of flavins enabled a highest bioelectricity output in microbial fuel cells. Nano Energy 2018;50:639-48.

31. Yang X, Ma X, Wang K, Wu D, Lei Z, Feng C. Eighteen-month assessment of 3D graphene oxide aerogel-modified 3D graphite fiber brush electrode as a high-performance microbial fuel cell anode. Electrochim Acta 2016;210:846-53.

32. Peng W, Li H, Liu Y, Song S. Effect of oxidation degree of graphene oxide on the electrochemical performance of CoAl-layered double hydroxide/graphene composites. Appl Mater Today 2017;7:201-11.

33. Tan P, Bi Q, Hu Y, Fang Z, Chen Y, Cheng J. Effect of the degree of oxidation and defects of graphene oxide on adsorption of Cu2+ from aqueous solution. Appl Surf Sci 2017;423:1141-51.

34. Yu H, Zhang B, Bulin C, Li R, Xing R. High-efficient synthesis of graphene oxide based on improved hummers method. Sci Rep 2016;6:36143.

35. Jin H, Zhu L, Jin S, Jiang L, Zou Y. Raman spectroscopy analysis of graphene oxide-enhanced textiles. J Raman Spectrosc 2021;52:843-8.

36. Li IL, Chen SF, Zhai JP. The Raman spectrum of graphene oxide decorated with different metal nanoparticles. Conference on AOPC 2015: Micro/Nano Optical Manufacturing Technologies; and Laser Processing and Rapid Prototyping Techniques; 2015 May 5-7. Beijing; 2015.

37. Rocha EM, Mota FS, Vilar VJ, Boaventura RA. Comparative analysis of trace contaminants in leachates before and after a pre-oxidation using a solar photo-Fenton reaction. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2013;20:5994-6006.

38. Han Z. XRD/XPS study on oxidation of graphite. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/XRD-XPS-Study-on-Oxidation-of-Graphite-Zhi/dc6065d97b67b06ab30ab05ec3845b2237a2edb4#citing-papers [Last accessed on 8 Mar 2023].

39. Jiang C, Yang Q, Wang D, et al. Simultaneous perchlorate and nitrate removal coupled with electricity generation in autotrophic denitrifying biocathode microbial fuel cell. Chem Eng J 2017;308:783-90.

40. Samsudeen N, Radhakrishnan TK, Matheswaran M. Bioelectricity production from microbial fuel cell using mixed bacterial culture isolated from distillery wastewater. Bioresour Technol 2015;195:242-7.

41. Huang G, Zhang Y, Tang J, Du Y. Remediation of Cd contaminated soil in microbial fuel cells: effects of Cd concentration and electrode spacing. J Environ Eng 2020;146:04020050.

42. Simeon MI, Asoiro FU, Aliyu M, Raji OA, Freitag R. Polarization and power density trends of a soil-based microbial fuel cell treated with human urine. Int J Energy Res 2020;44:5968-76.

43. Kakarla R, Min B. Evaluation of microbial fuel cell operation using algae as an oxygen supplier: carbon paper cathode vs. carbon brush cathode. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2014;37:2453-61.

44. Hwang JH, Ryu H, Rodriguez KL, et al. A strategy for power generation from bilgewater using a photosynthetic microalgal fuel cell (MAFC). J Power Sources 2021;484:229222.

45. Commault AS, Laczka O, Siboni N, et al. Electricity and biomass production in a bacteria- Chlorella based microbial fuel cell treating wastewater. J Power Sources 2017;356:299-309.

46. Bazdar E, Roshandel R, Yaghmaei S, Mardanpour MM. The effect of different light intensities and light/dark regimes on the performance of photosynthetic microalgae microbial fuel cell. Bioresour Technol 2018;261:350-60.

47. Lin CC, Wei CH, Chen CI, Shieh CJ, Liu YC. Characteristics of the photosynthesis microbial fuel cell with a Spirulina platensis biofilm. Bioresour Technol 2013;135:640-3.

48. Gouveia L, Neves C, Sebastião D, Nobre BP, Matos CT. Effect of light on the production of bioelectricity and added-value microalgae biomass in a photosynthetic alga microbial fuel cell. Bioresour Technol 2014;154:171-7.

49. Akhavan O, Ghaderi E. Toxicity of graphene and graphene oxide nanowalls against bacteria. ACS Nano 2010;4:5731-6.

50. Gurunathan S, Han JW, Dayem AA, Eppakayala V, Kim JH. Oxidative stress-mediated antibacterial activity of graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Nanomedicine 2012;7:5901-14.

51. Wang Z, Zhang Z, Xia L, et al. Sulfate induced surface modification of Chlorella for enhanced mercury immobilization. J Environ Chem Eng 2022;10:108156.

52. Zhang Y, Haris M, Zhang L, et al. Amino-modified chitosan/gold tailings composite for selective and highly efficient removal of lead and cadmium from wastewater. Chemosphere 2022;308:136086.

53. Wu C, Gao J, Liu Y, et al. High-gravity intensified electrodeposition for efficient removal of Cd2+ from heavy metal wastewater. Sep Purif Technol 2022;289:120809.

54. Zhao L, Yu G, Lv M, Huang X, Zhu H, Chen W. 2D RhTe monolayer: a highly efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. J Colloid Interface Sci 2023;629:971-80.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].