A communication toolkit for the most impactful symptoms of Fabry disease: co-creation with Fabry disease patients and their treating clinicians in the UK

Abstract

Aim: To co-create a communication aid with patients with Fabry disease (FD) and FD specialists.

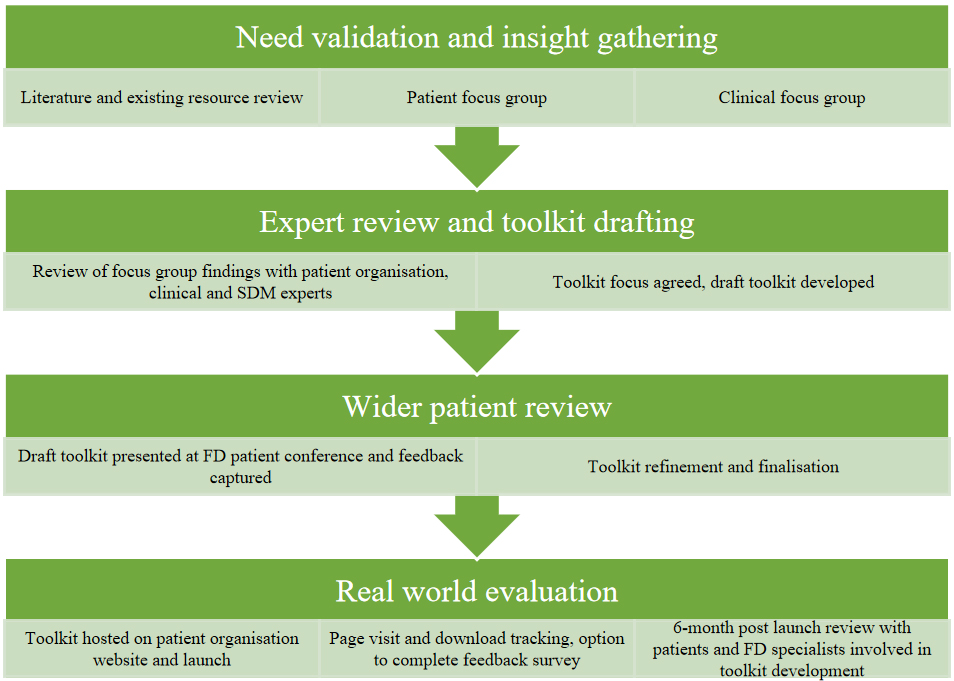

Methods: The co-development of the aid involved four steps: (1) need validation and insight gathering through focus groups and review of existing resources and literature; (2) expert review of focus group findings and drafting of the aid; (3) wider patient review of the draft materials at a FD patient conference; and (4) real-world evaluation following the aid’s launch.

Results: Eight patients participated in one focus group and five FD specialists participated in another. In a wider patient review, a feedback survey was completed by 57 patients. Patients in the focus group reported pain, fatigue and gastrointestinal symptoms as most impactful. Most patients preferred a shared rather than a paternalistic approach to decision-making and FD specialists agreed that all decisions should be shared. Insight gathering revealed that barriers to shared decision-making (SDM) included patient fears of being dismissed, challenges to recall or communication and time constraints. Enablers to SDM included patient empowerment, patient preparation for appointments and positive relationships between patients and healthcare professionals. Overall, 97.7% (42/43) of patients participating in a survey considered that the toolkit would/might encourage them to discuss concerns with their FD specialist.

Conclusion: Insights from the study underline the need for a communication aid to facilitate patient preparation for appointments, discussions and decisions about FD. The resulting toolkit has been co-created to empower patients and help specialists and patients make the best decisions for each individual.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Fabry disease is a rare, X-linked, multisystem lysosomal disorder caused by a mutation in the GLA gene that leads to reduced activity of the enzyme alpha-galactosidase A and, subsequently, progressive glycolipid accumulation in various tissues throughout the body[1,2]. The prevalence of Fabry disease is estimated at 1-5 per 10,000 individuals[3]. There are a spectrum of clinical phenotypes ranging from the “classic” severe phenotype in males without residual enzyme activity to a nonclassical phenotype, which has a more variable disease course[4,5]. In the “classic” phenotype, patients develop characteristic symptoms, such as pain, cornea verticillata and angiokeratoma in childhood or adolescence and suffer from long-term, life-threatening complications, including heart disease, stroke and progressive renal failure[1,4,5]. The nonclassical phenotype is generally milder with a later onset[4,5]. Symptoms of Fabry disease, including pain, fatigue and gastrointestinal issues, can have a major impact on patients’ quality of life[6]. Available treatments include specific treatments such as enzyme replacement therapy or pharmacological chaperone therapy[1,2,7]; supportive care is also often required[6].

Shared decision-making (SDM) is defined as “a collaborative process that involves a person and their healthcare professional (HCP) working together to reach a joint decision about care…” and is based on the sharing of evidence-based information about management options and consideration of a person’s preferences, beliefs and values[8]. SDM has been championed, particularly in chronic disease management, as an ideal strategy as it could improve the quality of the decision-making process for patients, support them to make treatment decisions that match their values and goals, and improve treatment adherence and even patient outcomes[9]. Since it was first launched onto the UK’s policy agenda in 2010, SDM has gradually become enshrined in National Health Service (NHS) strategy[10], is increasingly embedded into UK healthcare policy[10], and has been included in regulatory frameworks, such as the General Medical Council’s professional standards for doctors[11]. In 2021, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published guidance on how to incorporate SDM into mainstream care across all healthcare settings[8]. Increasing recognition of the importance of SDM, along with its integration into clinical guidelines and/or healthcare policies, has also been reported in other European countries and the USA[12-15].

In the UK, patients with Fabry disease are managed by multidisciplinary teams led by physicians at specialist centres[16]. Patients are usually seen once or twice a year at these centres and undergo a range of investigations according to a nationally agreed standard operating procedure[7]. In lifelong conditions such as Fabry disease, they may be presented with different therapeutic and diagnostic options and choices at different stages of their disease. The principles of SDM between patients and their healthcare providers are intended to facilitate these decisions and allow patients to take an active role in the management of their condition. Information on Fabry patients’ experiences of SDM is limited; however, the UK Care Quality Commission found that individuals with long-term physical or mental health conditions were among those least likely to feel involved in decisions about their treatment and care[17]. In a German study involving 101 structured interviews with patients with rare diseases, their families and health professionals, an SDM agreement was rarely reported[18]. Results from a Japanese survey identified gaps between patients with Fabry disease and their physicians concerning which symptoms most affected quality of life, disease severity, how well symptoms were controlled and advantages/disadvantages of treatment[19]. These studies suggest potential value of further integration of SDM in Fabry disease and other rare diseases[18,19]. Such a strategy is vital as more treatment options become available and there is increased understanding of Fabry disease, its impacts and management approaches[20,21].

Barriers to the routine implementation of SDM in rare diseases such as Fabry disease include the use of a traditional paternalistic approach; insufficient training and education of HCPs on the value and implementation of SDM; limited patient knowledge and confidence; changing circumstances and needs across the patient’s disease trajectory; inadequate integration into multidisciplinary team care; time constraints during appointments; and limited use in existing practices and procedures[22]. National and European guidelines for Fabry disease rarely include the management of patient reported symptoms or include them as indicators for starting Fabry specific treatment, which may act as a further barrier to patients discussing the signs and symptoms most important to them with their specialists[23]. Such discussions are fundamental to SDM. Patient decision aids (PDAs) are designed to facilitate decision-making when there are multiple management options with benefits and harms that people may value differently, and they are one potentially valuable tool to help overcome some of these barriers and embed SDM in practice[24]. Findings from a Cochrane review showed that PDAs improve knowledge, help patients clarify their values, lead to more accurate risk perceptions and decrease patient passivity in decision-making, improving patient-clinician communication[24]. However, additional or more general tools are likely to be required to address all the barriers and ensure successful SDM in Fabry disease, including tools assisting the capture and understanding of patient experience of symptoms and impacts, patient preference for their level of input in decisions and patient feedback on their greatest challenges and concerns.

This study aimed to gather insights from patients with Fabry disease and their specialists on the current state of, and unmet needs in, SDM in Fabry disease and then to co-develop communication aid to address these unmet needs. The communication toolkit was created to support patients with Fabry disease by empowering them to ask questions and request information as well as play an active role (to the degree they wish to) in the decisions made about management of their condition.

METHODS

A mixed-methods approach was used, incorporating evidence synthesis, qualitative data collection, co-produced resources, and pilot-testing.

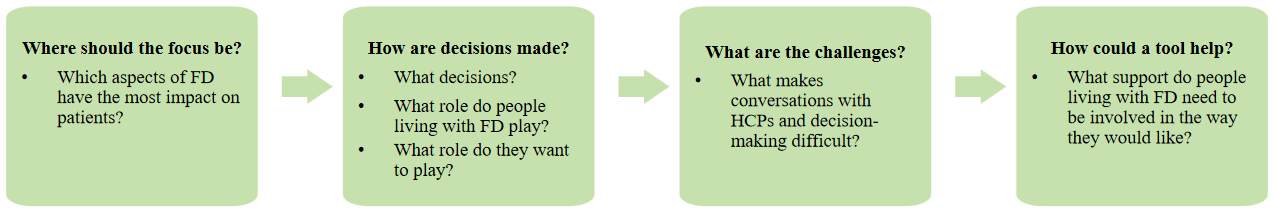

A series of questions were developed to guide toolkit development [Figure 1].

Figure 2 illustrates the steps in the development and testing of the toolkit.

At each stage of development, the communication toolkit was co-created by patients and Fabry disease specialists with involvement of other key stakeholders including a patient organisation (Society for Mucopolysaccharide and Related Diseases, UK), and clinical and SDM experts. While this was an industry led initiative, the content was developed independently to ensure a balanced, evidence-based, and objective representation of the subject matter. Internal review processes were in place to safeguard editorial integrity and prevent undue influence from commercial interests.

Need validation and insight gathering

Literature search and review of existing resources

A literature search was conducted to identify Fabry SDM support materials or PDAs and any previous research in Fabry disease on:

• Experience, priorities and unmet needs in decision-making;

• Development of SDM support materials;

• Application and evaluation of SDM.

PubMed, Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases and www.nice.org.uk were searched for relevant literature, guidelines and PDAs. A Google search was also performed to identify any additional grey literature, and web-based patient support materials. Search terms used were:

1. (Shared decision-making OR decision-making aids) AND Fabry disease;

2. (Shared decision-making OR decision-making aids) AND lysosomal storage disorders;

3. (Shared decision-making OR decision-making aids) AND inherited metabolic disorders;

4. (Shared decision-making OR decision-making aids) AND rare disease;

5. Shared decision-making AND (barriers OR implementation).

The PubMed and Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases searches were limited to articles published from the year 2000 onwards. No date limit was applied to the search of www.nice.org.uk (Becasue the first date of a NICE published guideline was 2003). The first 100 results from the Google search were reviewed. Backward searches (manual review of reference lists for additional relevant citations) were also conducted. Search results were first screened through review of titles and abstracts and then assessed for inclusion/exclusion.

Inclusion criteria:

• Original article in English language;

• Specific to or includes Fabry disease;

• Relevant to SDM.

Exclusion criteria:

• Duplicate articles;

• Not relevant to Fabry disease or SDM.

Focus groups

Insights were gathered and needs validated during two 3 h virtual focus groups, one involving individuals with Fabry disease and the other involving Fabry disease specialist consultants and Fabry disease specialist nurses working in the UK. All focus group participants provided informed consent, including consent for audio recording, and semi-structured discussion guides were used.

Individuals with Fabry disease were invited to take part via the Society of Mucopolysaccharide and Related Diseases, which shared the invitation with all their Fabry members. Patient inclusion criteria were: over the age of 18 with a confirmed (self-reported) diagnosis of Fabry who have access to a personal computer (PC) or laptop with a stable internet connection. Patients who were currently enrolled in a clinical trial were excluded. The patient focus group took place on 28 September 2023 via Zoom and was audio recorded and professionally transcribed. Insights from the patient focus group were used to develop the discussion guide for the Fabry disease specialist focus group.

Known Fabry disease specialists were invited to participate in the clinical focus group, which took place via Zoom on 29 January 2024. The discussion was audio recorded and professionally transcribed.

Transcripts from both focus groups were analysed using NVivo software and an inductive thematic approach was taken according to the six Braun and Clarke steps[25]. Slide kits of the findings were produced to share with the project expert advisors and insights from the focus groups were compared to existing Fabry disease patient SDM resources using gap analysis.

The focus groups were performed according to the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) Code of Practice and British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association (BHBIA) guidelines[26,27].

Expert review and toolkit drafting

Findings from the two focus groups were presented to a patient organisation (Society for Mucopolysaccharide and Related Diseases, UK) and clinical and SDM experts (the authors of this paper), to ensure that the insights were representative of wider patient and clinical experience and to define the focus and content of the toolkit. A standards framework for SDM support tools, published by NICE, was also consulted during the drafting of the toolkit[28].

Wider patient review

The development of the toolkit was an iterative process of review and refinement which included presentation of the draft toolkit [Supplementary File 1] to a Fabry patient audience at the Fabry Matters Conference, 1-3 March 2024, Wyboston, Bedford, UK, which was hosted by the Society of Mucopolysaccharide and Related Diseases. Audience members completed a live feedback survey during the presentation which consisted of multiple-choice and open text questions. The survey was completed via a conference app with informed consent prior to participation. Participants were able to skip questions if they wished; thus, the number responding to each question could vary. Participants also provided further feedback at the end of the presentation during the question-and-answer session. Survey results were analysed in Excel.

Real world evaluation

The toolkit was launched on the Society of Mucopolysaccharide and Related Diseases’ website on 22 August 2024[29]. Website analytics (number of views and downloads) are being tracked and users have the option to register their interest in completing a short feedback survey. The participants of the focus groups will also be asked for their feedback on the toolkit and whether they/their patients have used it.

RESULTS

Literature search

The literature search revealed only one study in Fabry disease related to SDM[19].

This cross-sectional study in Japan involved an online survey of Fabry disease patients and their treating physicians conducted in 2021. It included 30 paired responses where both the patient (n = 30) and their own treating physician (n = 13) both completed the survey, Validated tools [the 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9) and Shared Decision Making Questionnaire-Physician Version (SDM-Q-Doc)] were used to assess SDM in the paired sample and all participants answered additional questions, including perceptions of disease severity, progression and symptoms affecting patient’s quality of life.

The mean age of patients was 52.2 years and 46.7% male. Although there was overall agreement between patients and physicians in the items assessed by shared decision-making questionnaire (SDM-Q), the largest discrepancy was in the explanation of the advantages and disadvantages of different treatment options.

From the additional questions posed, the greatest difference in perception between patients and physicians was seen in relation to the symptoms considered to have the most impact on quality of life. Patients most often cited sweating abnormalities (44.4%) and gastrointestinal symptoms (38.9%)-areas physicians rarely chose (0% for sweating; 11.8% for gastrointestinal).

The authors concluded that there was a need for a communication tool to support discussions with patients about symptoms that were important from their perspective and the physician’s perspective and that decision aids specific to Fabry disease treatment and adjunctive therapy were essential and should be developed collaboratively with physicians, the pharmaceutical industry and patients.

Existing Fabry disease resources

We identified 13 SDM support resources for patients with Fabry disease, including three resources on Fabry disease-specific treatments, four disease/symptom trackers, four symptom factsheets (on fatigue, pain, hearing loss and gastrointestinal issues) and two discussion aids [Supplementary File 2].

Research participant demographics

Patient focus group

Eight individuals were included in the patient focus group, including both male and female patients with self-reported classic or non-classic Fabry disease and those managed at five different specialist centres across the UK [Table 1].

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | All patients (n = 8) |

| Sex, female, n | 4 |

| Age Median (range), years | 49.0 (26-61) |

| Fabry disease type (self-reported), n Classic Non-classic | 5 3 |

| Specialist centre, n Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust Cambridge University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Addenbrookes) Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Queen Elizabeth Hospital | 4 1 1 1 1 |

| Fabry specific treatment, n Agalsidase beta Agalsidase alfa Migalastat No current treatment | 3 3 1 1 |

Fabry disease specialist focus group

This focus group included four consultants with 15-25 years’ experience working with Fabry patients and one nurse specialist. Participants were from four UK specialist centres: Cambridge University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Addenbrookes); Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester; University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; and Cardiff and Vale University Health Board, University Hospital of Wales.

Wider patient review

Fifty-seven patients with Fabry disease from the UK completed the feedback survey at the Fabry disease patient conference but not all answered every question.

Experience and impact of symptoms

Insights from patient focus group

Patients in the focus group reported pain, fatigue and gastrointestinal issues as the most impactful symptoms of their Fabry disease [Table 2].

Most impactful symptoms

| Pain | Fatigue | Gastrointestinal issues | |

| Description of symptom | Unpredictable, intermittent, pain crises, chronic | Unpredictable, debilitating and linked to pain and FD crises | Increased frequency and urgency of bowel movements (particularly after meals), nausea, abdominal pain and cramps |

| Impact | Disrupted sleep, daily activities planned to avoid overexertion that can lead to pain crises. May make them feel misunderstood and anxious | Negatively affects activities of daily life, mood and wellbeing, socialising, employment/finances and physical health | Negative impact on educational and workplace attendance, leisure activities, socialisation and employment options |

| Management | An ongoing, iterative process. While pain stabilisation is a priority, patients often feel they have no choice but to endure their pain | No reference point for “normal” energy levels and saw fatigue as something to “deal with” without seeking medical advice | May experience gastrointestinal issues for months or years before seeking medical advice or receiving a referral to a specialist. Symptoms could improve with modifications to diet and timing of meals |

Insights from Fabry disease specialists focus group

In their clinical experience, Fabry disease specialists considered pain to be the most impactful symptom for patients with classic Fabry disease, and gastrointestinal issues and fatigue to be the most impactful for those with non-classic Fabry disease. They were surprised that patients in the focus group had not mentioned the psychological impacts of Fabry disease.

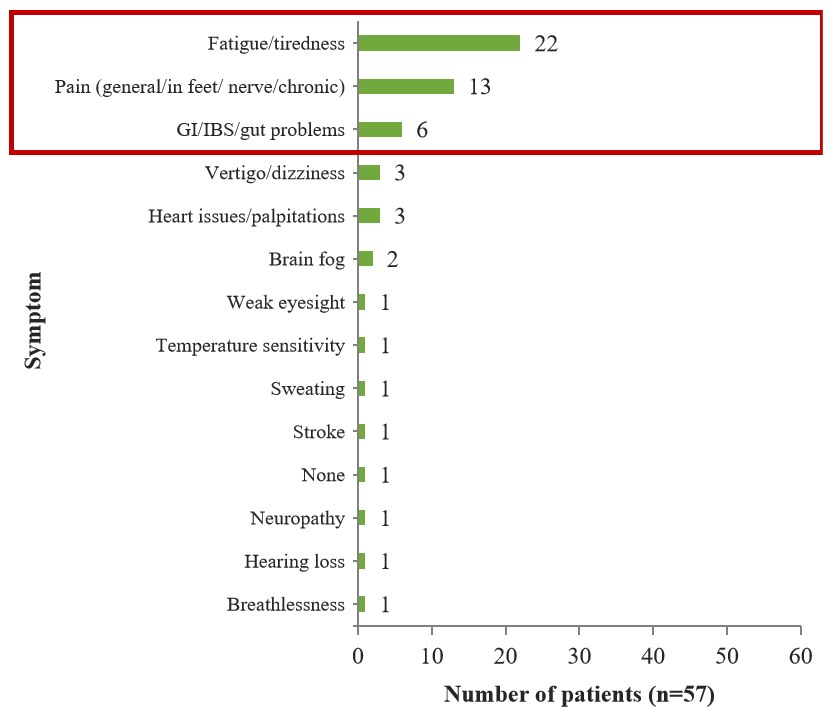

Insights from the wider patient review

Fatigue/tiredness was mentioned by the greatest number of patients (38.6%, 22/57) as having the biggest impact on their everyday lives [Figure 3].

Experience of decision-making

Patient focus group

Patients framed their disease management journey in terms of discussions with HCPs about solving problems rather than decisions to be made and at first found it difficult to identify decisions other than deciding to get tested if a family member was diagnosed first and starting, stopping or changing Fabry specific treatment. On further discussion, decisions about managing symptoms (e.g., pain and gastrointestinal issues), monitoring or treating heart issues, family planning and participating in a clinical trial were identified.

Patients had mixed experiences of collaborative or paternalistic decision-making, with most patients preferring SDM. Experiences of SDM were generally more positive with their Fabry disease specialists compared to non-specialist HCPs [e.g., general practitioners (GPs), cardiologists, emergency specialists]. Informed patients had a better decision-making experience and, therefore, it had been more challenging early on in their disease journey when they were less knowledgeable and experienced. Patients also expressed that decision-making is not one conversation but a process that can involve several discussions over time.

Patients struggled with decisions about whether to raise a concern and with whom. Some chose to “put up” with their symptoms instead of discussing them with their Fabry disease specialists.

Fabry disease specialist focus group

Fabry disease specialists considered that all decisions should be shared although they acknowledged that uncertainty in likely treatment outcomes and limited treatment options can restrict SDM. They felt that there needed to be a balance in responsibility between the clinician and their patient to identify or raise health concerns and that they should work together to address them. While the decision lies with the patient, it is important that patients know that decisions can be changed and that patients can choose to follow their clinician’s recommendation rather than decide for themselves. Specialists found SDM worked best if patients were empowered to raise their concerns and were engaged in their disease management.

Wider patient review

Over one half of patients (57.1%, 28/49) responding to the survey at the conference felt that they were involved in decision-making less than they would like to be, 40.8% (20/49) that they were involved in decision-making as much as they would like to be and 2.0% (1/49) that their involvement in decision-making was more than they would like.

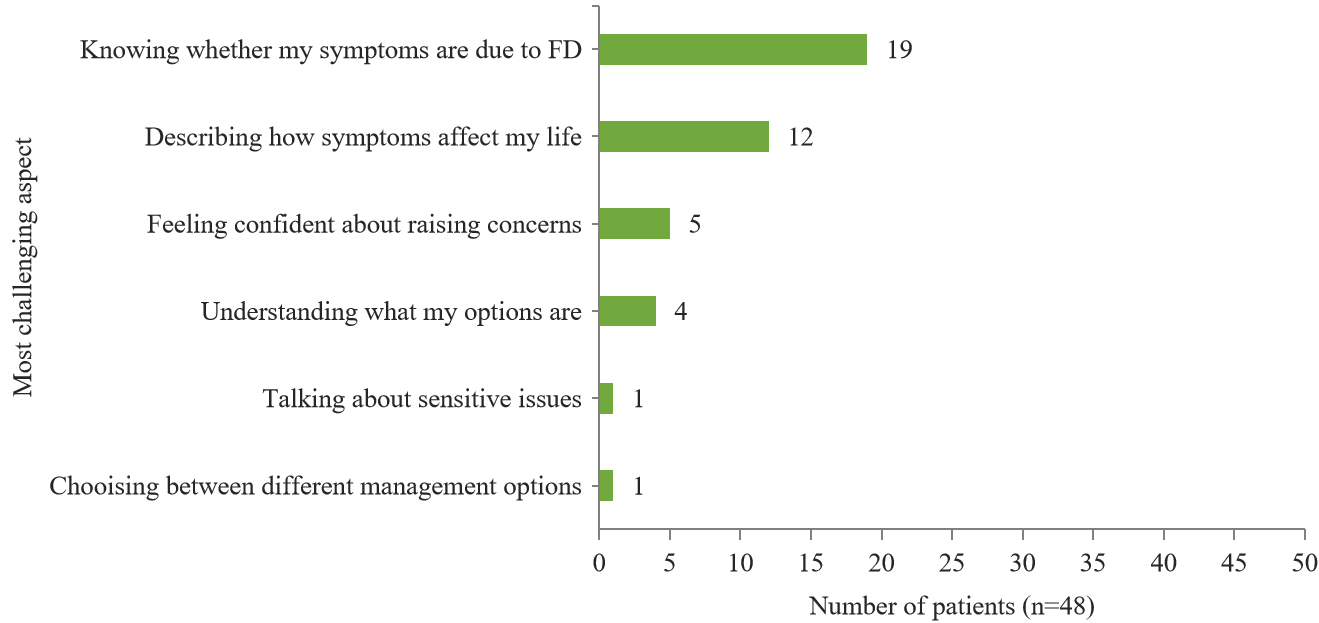

The greatest proportion of patients (39.6%, 19/48) reported that the most challenging aspect when talking to Fabry disease specialists was knowing whether their symptoms were due to the disease [Figure 4].

Barriers and facilitators to SDM

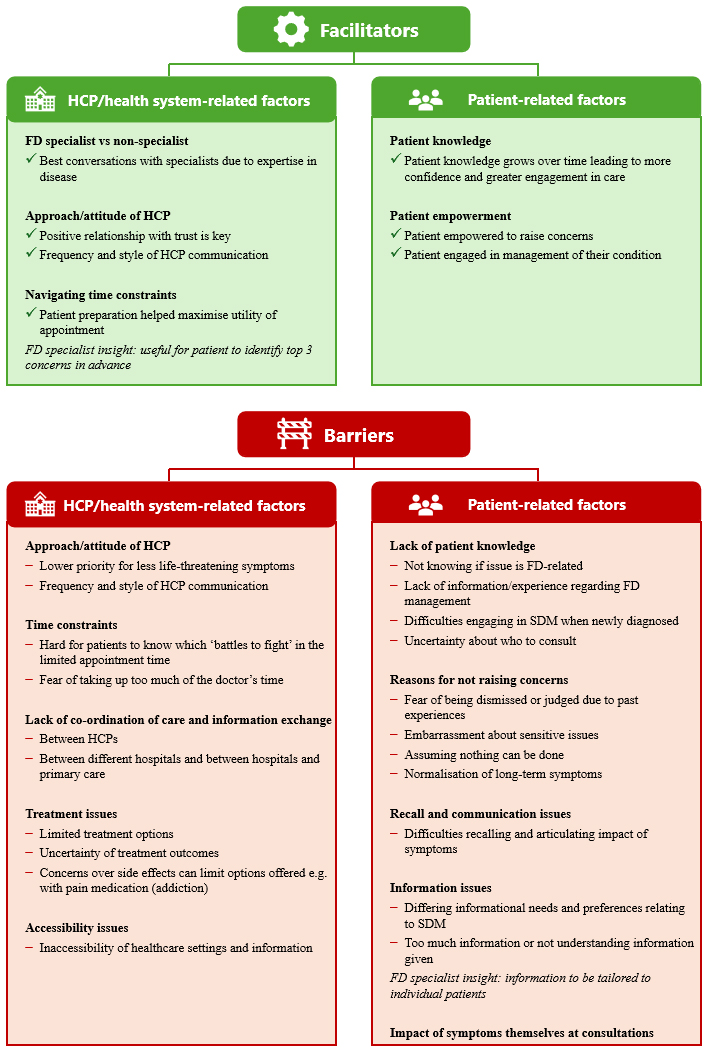

A number of barriers and facilitators to SDM were expressed during the three insight gathering phases and these are summarised in Figure 5.

Expert review

The expert reviewers considered the findings from the patient focus group to be representative of a wider patient experience. It was clear that pain, gastrointestinal issues and fatigue have the greatest impact on patients’ lives and that the toolkit should provide support for conversations between patients and their Fabry disease specialists for these symptoms.

The reviewers appreciated the importance of HCPs understanding the impact of Fabry disease symptoms on patients and the difficulties patients face when expressing this. They agreed that patients may feel the need to prove their symptoms and that they often would not go to their GP with anything related to Fabry disease. There was agreement that communication between Fabry and non-Fabry disease specialists is an ongoing issue. Reluctance of patients to engage in discussions about sensitive subjects and difficulties in understanding test results, or results not being passed to Fabry disease specialists, were common issues. HCPs’ concerns about pain medication addiction were familiar to the experts. They highlighted the importance of patient preparation before appointments with specialists and how a toolkit could help capture the patient’s story and experiences of an unpredictable disease. The importance of capturing the impact of symptoms, normalising seeking help for a range of Fabry disease symptoms and encouraging patients to think about the priorities for their care was stressed.

Gap analysis and toolkit development

By comparing the needs expressed by patients and specialists and the insight provided by expert reviewers with the existing Fabry disease specific resources [Supplementary File 2], key unmet needs in resources were identified. While resources for the three most impactful symptoms, support for discussions with healthcare providers and symptom trackers exist, support to overcome the barriers to raising concerns and decision-making support were lacking. We used these insights to develop the SDM toolkit and solicited feedback on the resulting draft at the Fabry disease patient conference [Table 3]. Feedback from the conference indicated that 97.7% (42/43) of patients considered that the toolkit would, or might, encourage them to discuss their concerns with their Fabry disease specialist. In response to the question of whether the toolkit would be helpful to discuss pain, 46.9% (15/32) of respondents answered “yes”, “probably” or “possibly”. Regarding stomach/digestive issues, 56.3% (18/32) replied that they would or might find the toolkit helpful to discuss stomach/digestive issues, whilst 62.1% (18/29) answered “yes/definitely” or “maybe/possibly” to the question of whether they would or may find the toolkit helpful to discuss fatigue. Regarding using the toolkit, 85.0% (34/40) stated that they would use some parts of the toolkit or use the toolkit.

Quantitative feedback from the Fabry disease conference

| Question* | Responses, n (%) | |

| Would this encourage you to talk to your FD specialist if you were concerned about something? (n = 43) | Yes | 25 (58.1) |

| Maybe | 17 (39.5) | |

| No | 1 (2.3) | |

| Would this help you to talk about pain? (n = 32) | Yes | 12 (37.5) |

| Probably/possibly | 3 (9.4) | |

| No | 4 (12.5) | |

| Don’t know | 1 (3.1) | |

| Comment only - positive | 1 (3.1) | |

| Comment only - suggestion | 9 (28.1) | |

| Comment only - other | 2 (6.3) | |

| Would this help you talk about stomach/digestive symptoms? (n = 32) | Yes | 15 (46.9) |

| Maybe | 3 (9.4) | |

| No | 2 (6.3) | |

| Don’t know/not applicable | 2 (6.3) | |

| Comment only - positive | 1 (3.1) | |

| Comment only - suggestion | 9 (28.1) | |

| Would this help you to talk about fatigue? (n = 29) | Yes/definitely | 14 (48.3) |

| Maybe/possibly | 4 (13.8) | |

| No | 2 (6.9) | |

| Comment only - positive | 3 (10.3) | |

| Comment only - suggestion | 5 (17.2) | |

| Comment only - other | 1 (3.4) | |

| Would you use a tool like this? (n = 40) | I think I would use some parts of this tool | 20 (50.0) |

| I think I would use this tool frequently | 14 (35.0) | |

| I would never use this tool | 3 (7.5) | |

| I would use this tool if changes were made | 3 (7.5) | |

The feedback gathered at the conference was used to refine the toolkit. The toolkit and supporting document can be found in Supplementary Files 3 and 4 and accessed at https://mpssociety.org.uk/resources/living-well-with-fabry[29]. Table 4 summarises how insights drove toolkit design throughout its development.

Key insights driving toolkit development

| Insights | How insights directed toolkit design |

| Barriers to raising concerns | Validating the barriers by including them using patients’ own language and providing responses that aim to normalise seeking help. Inclusion of quotes from clinicians and patients to highlight their support for SDM |

| Pain, GI issues and fatigue have the greatest impact on patients’ lives | Dedicated sections for the three symptoms where patients can note their concerns and questions with prompts to encourage communication. Inclusion of quotes from clinician validating patients experience of these symptoms |

| Challenges in communicating the impact of symptoms | “How your symptoms are affecting you” page to support patients to identify and describe the impact of their symptoms. Including prompts for activities of daily living affected by FD symptoms was mentioned by patients in the focus group. Symptom specific pages also include prompts relating to impacts |

| FD specialists felt that understanding what matters most to patients was vital | Providing prompts and spaces for patients to record symptoms and encourage thinking about and recording what is most important |

| Psychological impact of FD | “The way I am feeling” and “Questions about the way I am feeling” prompts in each symptom section |

| Recall of changes to symptoms and health concerns between appointments can be challenging for patients | Providing space for patients to record information they would like to share with their FD specialist between appointments Including a notes page for relatives or caregivers to record information that they would like to share with the patient’s FD specialist |

| Time restrictions of appointments may prevent patients from raising concerns or taking the time they need | Prompting patients to prepare for their appointment by considering their concerns, questions and priorities so they can discuss these more efficiently during their appointment |

| The concept of decision-making in healthcare was not well understood by patients | Language used reflects that used by patients to describe decision-making |

| Patients will have different preferences about their involvement in decision-making | Including prompts to support patients to share their decision-making needs and preferences |

| Patient desire to be more involved in decisions. | Question prompts to support patients to get the information and support they need to take an active role in decisions about their care |

| Decisions are iterative and revisited regularly | Toolkit aims to reflect this approach by guiding patients through decision-making processes that leave time and space for reflection, discussion with friends and family and review of decisions |

| Need for a better understanding of the treatment options available | Including question prompts to help patients request information about management strategies and support available to them |

| Support to make decisions | Decision-making grid for comparing options |

| Accessibility | Written in plain language with consideration given to the amount of text and design to assist a lay audience to navigate the content. Distributed in hard copy and hosted online as a PDF for printing at home and an editable PDF that could be downloaded and completed on an electronic device. A large print version for the visually impaired may be developed in the future |

| Other sources of support | Signposting to the Society for Mucopolysaccharidosis and Related Diseases for more information and support |

Real world evaluation

As of 29 July 2025, the toolkit landing page hosted on the Society for Mucopolysaccharidosis’ website had been visited by 476 unique visitors from 21 countries, mostly the UK (n = 356 visitors), USA (n = 43), Germany (n = 15) and Italy (n = 15). A total of 127 visitors had downloaded at least one of the documents available {toolkit for printing [n = 68]; toolkit editable PDF [n = 37]; supporting documentation explaining the background and use of the toolkit [n = 55]}.

DISCUSSION

Patients in focus groups reported pain, fatigue and gastrointestinal issues as their most impactful symptoms of Fabry disease. This was validated by patients attending a Fabry disease conference where the symptom reported as most impactful by the greatest proportion of patients was fatigue/tiredness followed by pain and then gastrointestinal symptoms. Patients viewed their journeys as a series of problems to be solved rather than as decisions to be made and struggled with decisions about whether to raise a concern and with whom. Most preferred SDM rather than a paternalistic approach to their care, a view echoed by Fabry disease specialists. However, less than half stated that they were involved in decision-making as much as they would like to be. Over a third stated that the most challenging aspect when discussing their symptoms with a Fabry disease specialist was knowing if these symptoms were related to Fabry disease. Patient organisations and clinical and SDM experts agreed that these issues were representative of a wider patient experience. Our findings suggest that partnership between patients and their treating Fabry disease specialists is the optimal model for decision-making in this disease. The importance of this collaboration between patients and those involved in their care is reflected in the co-creation of the toolkit throughout its development.

HCPs can have a strong influence on patient decision-making. However, patients and HCPs may have differing priorities. A study of patients with multiple sclerosis showed that patients’ goals focused on the impact of specific symptoms on their everyday lives while HCPs’ goals were directed at slowing down disease progression[30]. In the current study, everyday symptoms were highlighted by patients as impacting their daily lives, and not the potentially life-threatening symptoms of Fabry disease, which are often the main focus of specialists. SDM ensures that patient priorities are taken into account whilst also providing the opportunity for increasing understanding among patients to facilitate management of longer-term outcomes including organ dysfunction.

This communication toolkit could improve conversations between patients and their clinicians and help patients to prepare for and maximise the utility of appointments when time is limited. Patients should feel empowered; in the current study, both patients and Fabry disease specialists wanted patients to be involved in decisions. Patients may have different preferences for their level of involvement in decision-making, but they can be involved as much or as little in SDM as they want. There are, however, various barriers and facilitators to SDM engagement and implementation. In the current study, these broadly encompassed two distinct categories. The first was HCP and system-related barriers, such as challenges of SDM across a multidisciplinary team and various healthcare settings, limited appointment frequency with restricted time, limited treatment options and accessibility issues. The second was patient barriers, such as limited disease knowledge, lack of confidence/poor past experiences of symptom sharing, poor symptom recall and varying needs and preferences. Facilitators of SDM included appointments with Fabry disease specialists as opposed to non-specialists due to their expertise, patient empowerment, physician-patient trust and patient preparedness for appointments (to maximise use of limited time).

Key lessons from the Making Good Decisions in Collaboration (MAGIC) NHS programme[31] included the following challenges to SDM implementation: a perception that SDM was already happening; reports from clinicians that patients do not want SDM; lack of the right tools to support SDM; difficulties measuring the effectiveness of SDM, and the extra work required to use SDM alongside other often conflicting demands and priorities. Results from the current study demonstrate that most Fabry disease patients are not involved in decision-making as much as they would like despite both patients and their Fabry disease specialists supporting the principle of SDM. This new toolkit could help address the lack of the right tools. Accommodating SDM amongst other demands on a physician’s time could be mitigated by sharing the responsibility amongst the wider care team, e.g., involving nurses to solicit patients’ preferences[31].

The communication toolkit could have many benefits for patients and clinicians as evidence suggests that SDM may improve patient satisfaction, confidence in the decision made, clinical outcomes and adherence to treatment recommendations[32-35]. In a systematic review on SDM and patient outcomes, only 47% of behavioural outcomes and 25% of health outcomes had a positive association with SDM. However, better measures of SDM are needed so these findings could underrepresent the association between SDM and patient outcomes[36].

Two of the main themes in a systematic review of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to SDM were patient’s knowledge about treatment options and their preferences and goals and patients’ perception of their capacity to have an influence on decisions made[37]. In a systematic review of HCPs’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to SDM, the most common barriers were lack of time and lack of applicability due to patient characteristics or the clinical situation. The most common facilitators were the motivation of the HCP and positive impacts on patient outcomes and the clinical process[38]. Finally, a working group identified barriers to SDM in rare disease as a paternalistic HCP approach, patient lack of confidence, knowledge and perception that they have a lesser role to play in decision-making, changing needs over time, insufficient co-ordination of care, lack of time at appointments and HCP perception that SDM is already occurring[22]. The Fabry communication toolkit targets some of these barriers by empowering patients, supporting more efficient appointments, highlighting the importance of SDM to both patients and HCPs and providing a prompt for patients and Fabry disease specialists to discuss changes in patients’ needs that should be addressed.

The Fabry communication toolkit is not strictly a PDA according to the NICE definition[24,28] as it does not state the decision to be made or the options; however, it does provide an aid for discussion and empowers the patient to think about their priorities. In a multi-systemic disease such as Fabry, a more general toolkit that focuses on symptoms that affect patients the most and encourages discussion of concerns may be preferable. It also meets several other requirements presented by NICE for PDAs: it supports patient communication with HCPs, uses accessible language and was co-created by patients and professionals[28]. As the toolkit aids in SDM but does not meet all PDA criteria, it is probably better described as a communication tool or a decision guide[39,40].

Little has been written about development of SDM aids. Waldron et al. (2020) developed a program theory for SDM with contexts, mechanisms and the outcome of engagement in SDM[41]. Meanwhile, Col et al. (2017) used the results from their study comparing the treatment goals of patients and their HCPs to develop a preference assessment tool to be expanded into an SDM for patients with multiple sclerosis[30]. In this paper, we provide a detailed description of how the Fabry disease communication toolkit was

Strengths of this study include the detailed description of the toolkit’s development and the involvement of patients, Fabry disease specialists, and clinical and SDM experts in the process. A limitation is that the Fabry disease conference patient audience comprised only UK patients already engaged in managing their condition, who may not be representative of the broader patient population. Review and feedback on the communication toolkit from a broader range of patients, including those from multiple countries with different levels of awareness and adoption of SDM, may have been beneficial. However, clinical and SDM experts did consider the identified issues to be representative of a wider patient experience and in the

Analysis of activity on the Society for Mucopolysaccharidosis’ website, where the communication toolkit is hosted, indicates significant interest in this resource from the Fabry community. There were 356 unique visitors from the UK, where the estimated symptomatic Fabry population is approximately 1,400 in total[41,42], and where hard copies of the toolkit were also available to patients and clinicians following its distribution to all specialist clinical centres in the UK that manage patients with Fabry disease.

Conclusion

Insights from the focus groups and the conference audience demonstrated the need for a communication aid in Fabry disease to aid preparation, discussions and decisions about disease management. The resulting toolkit should facilitate communication between patients and healthcare providers and enable Fabry disease specialists and patients to make the best choices for the individual patient.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

Chiesi Limited funded the development of the communication toolkit, in collaboration with Rare Disease Research Partners who undertook the research development, data collection, analysis and medical writing for the project; medical writing for the manuscript was supported by independent medical writers, Krys Dylewska and Emma Moorhouse. We would like to thank all patients, Fabry disease specialists (including Dr. Fiona Stewart), patient organisations and experts for their participation in the development of the toolkit.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study, data interpretation and design of the communication toolkit: Bunn K, Gaffney S, Iqbal K, Kenny T

Acted as expert advisors and made substantial contributions to data interpretation and design of the SDM toolkit: Hughes D, Thomas S, Joseph-Williams N

Availability of data and materials

The datasets collected and analysed during the current study are not publicly available for reasons of patient confidentiality.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was initiated, organised and fully funded by Chiesi Limited. The writing of the manuscript was fully funded by Chiesi Limited.

Conflicts of interest

Hughes D is the Guest Editor of the Special Issue “Advancements in Diagnosis and Treatment of Fabry Disease 2.0” of the Rare Disease and Orphan Drugs Journal, but was not involved in any steps of editorial processing, notably including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. Hughes D has received honoraria for speaking and advisory boards from Chiesi and is a trustee of the MPS society. Thomas S is an employee of the MPS Society which has received grants for its patient support services, website redevelopment project, mental health and wellbeing services, participation and chairing advisory boards, travel and accommodation for attending satellite symposiums and meetings. Joseph-Williams N has received honoraria for consultancy from Chiesi. Bunn K, Gaffney S, Iqbal K and Kenny T are full-time employees of Chiesi Limited.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was not required according to the HRA decision tool (https://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/). Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the Fabry disease conference and in the focus groups. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association’s Legal and Ethical Guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Mehta A, Hughes DA. Fabry disease. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al, Editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle: University of Washington; 2002 [Updated 2024 Apr 11]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1292/?utm_source [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

2. Bokhari SR, Zulfiqar H, Hariz A. Fabry disease. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [Updated 2023 Jul 4]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435996/?utm_source [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

3. Orphanet. Fabry Disease. Updated 2022. Available from: https://www.orpha.net/en/disease/detail/324 [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

4. Desnick RJ, Ioannou YA, Eng CM. α-galactosidase a deficiency: Fabry disease. In: Valle DL, Antonarakis S, Ballabio A, Beaudet AL, Mitchell GA, Editors. The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019. Available from: https://ommbid.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2709§ionid=225546984 [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

5. Arends M, Wanner C, Hughes D, et al. Characterization of classical and nonclassical Fabry disease: a multicenter study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:1631-41.

6. Berry L, Walter J, Johnson J, et al. Patient-reported experience with Fabry disease and its management in the real-world setting: results from a double-blind, cross-sectional survey of 280 respondents. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2024;19:153.

7. British Inherited Metabolic Disease Group. Guidelines for the treatment of Fabry Disease; 2025. Available from: https://bimdg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/2025.05.30.Fabry-Clinical-Guidance.pdf [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

8. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Shared decision making; 2021. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng197/resources/shared-decision-making.pdf-66142087186885 [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

10. Coulter A, Edwards A, Elwyn G, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the UK. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2011;105:300-4.

11. General Medical Council. Decision making and consent; 2020. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/professional-standards/professional-standards-for-doctors/decision-making-and-consent [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

12. Hahlweg P, Bieber C, Levke Brütt A, et al. Moving towards patient-centered care and shared decision-making in Germany. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2022;171:49-57.

13. Davidson KW, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, et al.; US Preventive Services Task Force. Collaboration and shared decision-making between patients and clinicians in preventive health care decisions and US preventive services task force recommendations. JAMA 2022;327:1171-6.

14. Moumjid N, Durand MA, Carretier J, et al. Implementation of shared decision-making and patient-centered care in France: towards a wider uptake in 2022. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2022;171:42-8.

15. Matlock DD, Jackson LR 2nd, Sandhu A, Scherer LD. Past, present, and future of shared decision-making. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2024;17:e010584.

16. Hughes DA, Evans E, Milligan A, Richfield L, Mehta A. A multidisciplinary approach to the care of patients with Fabry disease. In: Mehta A, Beck M, Sunder-Plassmann G, Editors. Fabry disease: perspectives from 5 years of FOS. Oxford: Oxford Pharmagenesis; 2006. Chapter 35. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11587/ [Last accessed on 29 October 2025].

17. Care Quality Commission. Better care in my hands: a review of how people are involved in their care; 2016. Available from: https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/themed-work/better-care-my-hands-review-how-people-are-involved-their-care [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

18. Babac A, von Friedrichs V, Litzkendorf S, Zeidler J, Damm K, Graf von der Schulenburg JM. Integrating patient perspectives in medical decision-making: a qualitative interview study examining potentials within the rare disease information exchange process in practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2019;19:188.

19. Inagaki N, Tsuchiya M, Otani K, Nakayama T. Shared decision making between patients with Fabry disease and physicians in Japan: an online survey. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2022;32:100899.

21. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Pegunigalsidase alfa for treating Fabry disease; 2023. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta915 [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

22. Joseph-Williams N, Chakrapani A, Collin-Histed T, Greeney J, Gregory D. Shared decision making in rare disease in the United Kingdom, White Paper; 2021. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/395133038_White_Paper_-_SDM_in_Rare_Disease_White_Paper [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

23. Hughes DA, Aguiar P, Lidove O, et al. Do clinical guidelines facilitate or impede drivers of treatment in Fabry disease? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022;17:42.

24. Stacey D, Lewis KB, Smith M, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;1:CD001431.

25. Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 2019;11:589-97.

26. PMCPA. 2021 interactive ABPI Code of Practice; 2021. Available from: https://www.pmcpa.org.uk/the-code/previous-abpi-codes-of-practice/2021-interactive-abpi-code-of-practice/ [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

27. BHBIA legal and ethical guidelines for healthcare market research: your essential guide; 2024. Available from: https://www.bhbia.org.uk/guidelines-and-legislation/legal-and-ethical-guidelines [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

28. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Standards framework for shared-decision-making support tools, including patient decision aids; 2021. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/corporate/ecd8 [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

29. MPS Society. Living well with Fabry: a shared decision-making toolkit; 2024. Available from: https://mpssociety.org.uk/resources/living-well-with-fabry [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

30. Col NF, Solomon AJ, Springmann V, et al. Whose Preferences matter? A patient-centered approach for eliciting treatment goals. Med Decis Making. 2018;38:44-55.

31. Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Edwards A, et al. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ. 2017;357:j1744.

32. Edwards A, Elwyn G. Inside the black box of shared decision making: distinguishing between the process of involvement and who makes the decision. Health Expect. 2006;9:307-20.

33. Naik AD, Kallen MA, Walder A, Street RL Jr. Improving hypertension control in diabetes mellitus: the effects of collaborative and proactive health communication. Circulation. 2008;117:1361-8.

34. Wilson SR, Strub P, Buist AS, et al.; Better Outcomes of Asthma Treatment (BOAT) Study Group. Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;181:566-77.

35. Ben-Zacharia A, Adamson M, Boyd A, et al. Impact of shared decision making on disease-modifying drug adherence in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2018;20:287-97.

36. Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35:114-31.

37. Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:291-309.

38. Gravel K, Légaré F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Implement Sci. 2006;1:16.

39. The Health Foundation. Helping people share decision making: A review of evidence considering whether shared decision making is worthwhile. London; 2012. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/reports-and-analysis/reports/helping-people-share-decision-making [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

40. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Decision guides (mostly for any decision). Available from: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/decguide.html [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

41. Waldron T, Carr T, McMullen L, et al. Development of a program theory for shared decision-making: a realist synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:59.

42. Brennan P, Parkes O. Case-finding in Fabry disease: experience from the North of England. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2014;37:103-7.

43. Office for National Statistics. Population estimates for the UK, England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: mid-2023. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/annualmidyearpopulationestimates/mid2023 [Last accessed on 27 October 2025].

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].