Educating hematologists about Gaucher disease

Abstract

Gaucher Disease (GD) is a rare, non-malignant inherited lysosomal storage disorder with a strong hematological component. Although the disease is non-malignant, patients are at risk of developing future hematological malignancies. Hematologists are the largest specialty diagnosing the condition, but diagnosis is usually incidental, following investigation for unexplained splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, or anemia. Hematologists must be alert to the possibility of GD when patients present with unexplained moderate-to-severe splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, chronic anemia, and osteolytic bone disease. The major barriers to diagnosis are that the common presenting features of GD overlap with those of other common hematological conditions. As a result, GD education needs to be shifted from the spectrum of metabolic disorders into mainstream hematology, especially because fast and accurate diagnosis is important for both the individual patient and their wider family.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Gaucher Disease (GD) is a rare disease and favorable outcomes largely depend on appropriate expert prompt recognition and management of the disease. Hematology is by far the largest diagnosing specialty, with 75% of GD patients diagnosed and managed by hematologists[1]. In most cases, the appropriate diagnosis is established incidentally, following a bone marrow examination, as part of the investigation process for unexplained splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia or anemia[2,3]. Many comprehensive reviews, guidelines, global surveys and GD registries confirm that the hematologist often encounters GD within a broad, multisystem spectrum that can masquerade as hematologic malignancy, splenomegaly from other causes, or isolated cytopenias, making an evidence-based, organ-system-centred approach essential for early diagnosis[4-6].

Misdiagnosis is detrimental to patients, particularly when it results in unnecessary procedures such as splenectomy, liver biopsy, and treatment with corticosteroids.

THE GD DELPHI INITIATIVE

A Delphi technique was used to gain global expert consensus from a panel of 22 GD specialists (> 450 years of GD experience covering almost 3,000 patients)[7]. The initiative found that a lack of disease awareness, overlooking mild early signs of GD, and failure to consider GD in the differential diagnosis were major barriers to early diagnosis.

Hematologists and other physicians often miss these conditions, leading to frequent delays in diagnosis that negatively affect patients. This can result in additional complications and procedures, which are significantly associated with less favorable treatment outcomes. However, a favorable outcome depends on the prompt and appropriate recognition and management of the disease.

GD

GD is an inherited lysosomal storage disorder (LSD) characterized by the accumulation of the undigested disease substrate glucosylceramide (GC) in the cytoplasm of macrophages within the reticuloendothelial system[8]. Diagnosis of GD, particularly the milder phenotypes of Type 1 (GD1), is universally underdiagnosed worldwide, with 75% of patients found in Ashkenazi Jews compared with around 40% in other Caucasians[9,10]. GD has a prevalence of around 0.70 to 1.75 patients diagnosed per 100,000 patients and is associated with mild to moderate enzymatic activity and an absence of severe neuronopathic symptoms[11,12].

GD1 patients have an increased risk of developing autoimmune disorders, bone disease, and neoplastic disorders - including both hematological malignancies and solid tumors, but above all, multiple myeloma (MM)[13]. GD1 has a strong and complex hematological component, both in its initial clinical manifestations and in long-term disease complications[14].

GD AND THE HEMATOLOGIST

As mentioned above, hematologists play a significant role in the diagnosis and management of this disease. The clinical manifestations and laboratory results of GD1 should alert hematologists to consider GD1 in their differential diagnosis of patients presenting with thrombocytopenia, moderate-to-severe splenomegaly, chronic anemia, and osteolytic bone disease.

Another issue of concern is that, under the differential diagnosis of thrombocytopenia with splenomegaly on the OpenEvidence website, various hematological disorders are listed, but GD is not included. This further confirms the challenge we face in educating hematologists-in-training about these rare diseases.

Diagnostic confirmation hinges on specific laboratory tests that hematologists should pursue once GD1 is suspected on clinical grounds. Diagnosis typically begins with measuring β-glucocerebrosidase (GCase) activity in circulating leukocytes or dried blood spots, with markedly reduced activity confirming GD1; enzyme assay remains a central diagnostic pillar, complemented by genetic testing to define glucosylceramidase beta 1 (GBA1) gene mutations. This enzymatic confirmation is emphasized in expert reviews and practice guidelines and is central to establishing a GD1 diagnosis in hematology practice[15]. With regard to the differential diagnosis of pediatric patients, GD should be considered in any pediatric patient presenting with neurological manifestations.

Hematologists, when evaluating patients with abnormal clinical findings, need to consider GD1 and other rare LSDs, such as acid sphingomyelinase deficiency (ASMD; formerly known as Niemann-Pick disease types A/B), in their routine differential diagnostic thinking, as their signs and symptoms may overlap[16] [Table 1]. In a cross-sectional web-based survey among hematologists and gastroenterologists from Japan, hematologists were found to have a higher awareness of GD1[17]. It is evident that there is an unmet need for a deeper understanding of how to diagnose, consult on, treat, prevent, and manage this disease.

Common clinical features of GD, ASMD and hematological malignancies[16]

| Common features | GD | ASMD | Hematological malignancies |

| Anemia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Thrombocytopenia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bruise/bleeding | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hepatomegaly | Yes | Yes | Possibility |

| Splenomegaly | Yes | Yes | Possibility |

| Hyperferritinemia | Yes | Yes | No |

| Bone deformities | Yes | Yes | No |

| Abdominal symptoms | Yes | Yes | No |

| Growth delays | Yes | Yes | No |

| Lung disease | Yes | Yes | Possibility |

| HDL-C | No | Yes | No |

| Lymphadenopathy | No | No | Frequently |

| Leukopenia | No | No | Yes |

| Fever | No | No | Yes |

| Night sweats | No | No | Yes |

| Weight loss | No | No | Yes |

The treatment of GD1 must be personalized on an individual patient basis to help the hematologist monitor and evaluate the efficacy of the treatment. The aim is to restore disease manifestations and associated complications as close to normal as possible[18].

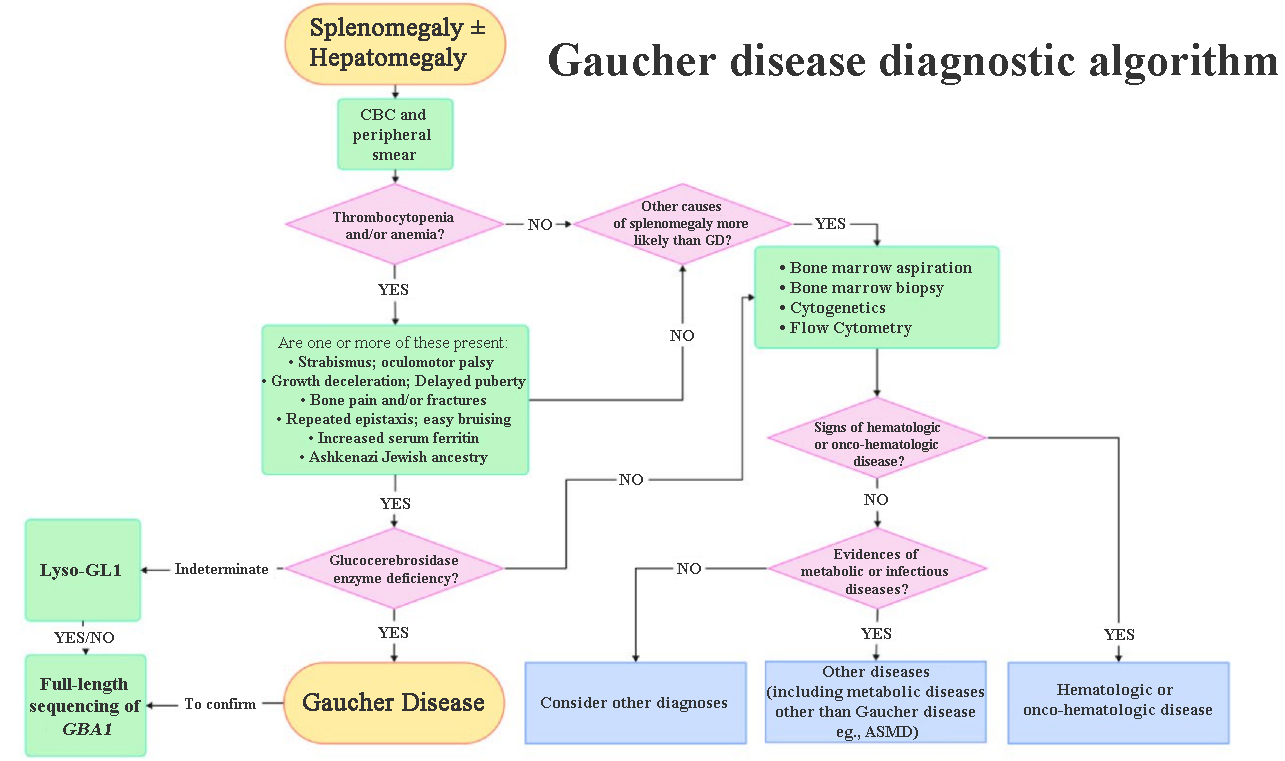

The main prompt from GD diagnostic algorithms is the importance of a readily available diagnostic test for GD. GD diagnostic algorithms will start with a complete blood count and review of a peripheral blood smear following a referral for a recently discovered splenomegaly and/or hepatomegaly [Figure 1][19]. This is performed to detect signs of thrombocytopenia or anemia. If the patient exhibits thrombocytopenia and/or anemia along with one or more of the other GD-related symptoms, the GCase enzyme level is assessed. If GCase deficiency is confirmed, a GD diagnosis is made. However, if GD is not confirmed then further tests are carried out to confirm either another metabolic disorder such as ASMD, a hematological malignancy or another diagnosis.

Figure 1. GD Diagnostic Algorithm. GD: Gaucher disease; ASMD: acid sphingomyelinase deficiency; CBC: complete blood count. Reproduced with permission from Luettel et al.[19]. Copyright © Elsevier, 2025.

EDUCATIONAL GAP

A question has to be asked concerning why the diagnosis may be missed. Is it a rare presentation of a common disease or a common presentation of a rare disease? The common presenting features of rare non-malignant disorders with a hematological presentation make it a challenging area for hematologists-in-training as many of these rare disorders have overlapping features. The concern is that hematologists-in-training often miss these conditions, leading to frequent delays in diagnosis that negatively affect patients and their family members or partners, resulting in additional complications and procedures and less favorable treatment outcomes. When gathering a family history, it is important for the hematologist-in-training to inquire about the presence of specific conditions and symptoms in affected blood relatives including those with a history of Parkinson’s disease. Specifically in relation to Parkinson’s disease and basal ganglia degeneration, patients should be monitored in collaboration with appropriate specialists to identify any potential disease progression or complications. Once a new case of GD is diagnosed, the hematologist in training should be able to provide information for family genetic counseling.

A classic common presenting feature is undiagnosed hepatosplenomegaly. More common hematological causes include myeloproliferative diseases (MPDs), chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), hairy cell leukemia (HCL), MM, thalassemia, pernicious anemia (PA), and sickle cell disease (SCD). The unknown causes could be a number of metabolic disorders such as GD1 and ASMD A/B, Tay-Sachs disease, Pompe disease, as they present with similar features[16]. Although it is important to distinguish GD1 from hematological malignancies such as MPDs, CML, HCL, and MM, it is important to know that GD1 and malignancies may also co-exist[20] [Table 1].

THE WAY FORWARD

The above highlights the need for education on rare non-malignant hematological conditions such as GD1, especially when timely and accurate recognition is important for the welfare of an individual patient and their wider family. In light of this, GD1 education needs to be shifted from the spectrum of metabolic disorders into mainstream hematology. Many common causes of misdiagnosis of GD1 are hematological in nature, with hematological malignancy, idiopathic thrombocytopenia, and anemia of chronic disease being the most frequent misdiagnoses.

THE EHA SWG GD TASK FORCE

The Board of the European Hematology Association (EHA) appointed the European GD Network as a Scientific Working Group (SWG) Task Force of the EHA at the EHA Annual Congress in Stockholm in June 2018.

Since its inception, the aim of the EHA SWG GD Task Force has been to increase and improve awareness of GD among hematologists within the EHA. To achieve this goal, the Task Force submitted a GD Curriculum for hematologists to the EHA Board for approval. This document provides a detailed description of the education required by hematologists-in-training to assess and manage patients with GD.

Perhaps the most challenging element of the curriculum content is ensuring that hematologists-in-training, with their limited training time, learn about rare hematological conditions, especially since most of these cases will end up in a tertiary referral unit. This is particularly important when timely and accurate recognition is crucial for patient welfare and when an effective treatment is available for the uncommon condition.

Although teaching rare classical hematologic conditions can be challenging, the rewards are substantial. These conditions, such as GD, do not follow the standard disease management that hematologists-in-training or lecturers usually expect. They often require a more thoughtful and nuanced approach so that hematologists-in-training can understand how to approach the diagnosis and treatment of patients with these rare classical conditions.

By focusing on a structured, case-based, and interactive approach, rare classical hematologic conditions such as GD can be demystified, helping hematologists-in-training become more confident in recognizing and managing the disease. The aim is to create a learning environment where the rarity of GD does not overshadow its importance in clinical practice. It is important for hematologists-in-training to understand that, although GD is not a malignancy, it still requires careful management.

It is probably helpful for hematologists-in-training if the lecturer discusses GD1 in the context of blood disorders that may mimic or overlap with hematologic malignancies in presentation. Although GD1 is

CONCLUSION

Diagnosing the cause of an illness in an individual patient must be based on whether specific criteria are fulfilled or not. The distinction between rare and common conditions is irrelevant, as it does not change the odds for a single patient[21].

When considering the differential diagnosis of a rare disease such as GD, first exclude all the more common conditions. Once the likely conditions have been excluded, begin to think outside the box and consider unusual conditions. At this point, it is important to be aware of the tests that are actually available for GD.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgements

I am pleased to acknowledge my fellow participants in the Global GD/Rare Disease Network: Sam Salek, Argiris Symeonidis, and Richard Soutar (Europe); and Steven Allen, Jeremy Lorber, Barry Rosenbloom, and Neil Weinreb (USA).

Authors’ contributions

The author contributed solely to the article.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

The author declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Mehta A, Belmatoug N, Bembi B, et al. Exploring the patient journey to diagnosis of Gaucher disease from the perspective of 212 patients with Gaucher disease and 16 Gaucher expert physicians. Mol Genet Metab. 2017;122:122-9.

2. Di Rocco M, Andria G, Deodato F, Giona F, Micalizzi C, Pession A. Early diagnosis of Gaucher disease in pediatric patients: proposal for a diagnostic algorithm. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:1905-9.

3. Mistry PK, Cappellini MD, Lukina E, et al. A reappraisal of Gaucher disease-diagnosis and disease management algorithms. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:110-5.

4. Nishimura S, Ma C, Sidransky E, Ryan E. Obstacles to early diagnosis of Gaucher disease. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2025;21:93-101.

5. Elstein D, Belmatoug N, Bembi B, et al. Twelve years of the Gaucher Outcomes Survey (GOS): insights, achievements, and lessons learned from a global patient registry. J Clin Med. 2024;13:3588.

6. Mistry PK, Sadan S, Yang R, Yee J, Yang M. Consequences of diagnostic delays in type 1 Gaucher disease: the need for greater awareness among hematologists-oncologists and an opportunity for early diagnosis and intervention. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:697-701.

7. Mehta A, Kuter DJ, Salek SS, et al. Presenting signs and patient co-variables in Gaucher disease: outcome of the Gaucher Earlier Diagnosis Consensus (GED-C) Delphi initiative. Intern Med J. 2019;49:578-91.

8. Roh J, Subramanian S, Weinreb NJ, Kartha RV. Gaucher disease - more than just a rare lipid storage disease. J Mol Med. 2022;100:499-518.

9. Nalysnyk L, Rotella P, Simeone JC, Hamed A, Weinreb N. Gaucher disease epidemiology and natural history: a comprehensive review of the literature. Hematology. 2017;22:65-73.

10. Wang M, Li F, Zhang J, Lu C, Kong W. Global epidemiology of Gaucher disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2023;45:181-8.

11. Castillon G, Chang SC, Moride Y. Global incidence and prevalence of Gaucher disease: a targeted literature review. J Clin Med. 2022;12:85.

12. Lepe-Balsalobre E, Santotoribio JD, Nuñez-Vazquez R, et al. Genotype/phenotype relationship in Gaucher disease patients. Novel mutation in glucocerebrosidase gene. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58:2017-24.

13. Ormazabal ME, Pavan E, Vaena E, et al. Exploring the pathophysiologic cascade leading to osteoclastogenic activation in Gaucher disease monocytes generated via CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:11204.

14. Revel-Vilk S, Szer J, Zimran A. Hematological manifestations and complications of Gaucher disease. Expert Rev Hematol. 2021;14:347-54.

15. Thomas AS, Mehta A, Hughes DA. Gaucher disease: haematological presentations and complications. Br J Haematol. 2014;165:427-40.

16. Cappellini MD, Motta I, Barbato A, et al. Similarities and differences between Gaucher disease and acid sphingomyelinase deficiency: an algorithm to support the diagnosis. Eur J Intern Med. 2023;108:81-4.

17. Yoshimitsu M, Ono M, Inoue Y, Sagara R, Baba T, Fernandez J. Cross-sectional web-based survey among haematologists and gastroenterologists in Japan to identify the key factors for early diagnosis of Gaucher disease. Intern Med J. 2023;53:930-8.

18. Biegstraaten M, Cox TM, Belmatoug N, et al. Management goals for type 1 Gaucher disease: an expert consensus document from the European working group on Gaucher disease. Blood Cells Molec Dis. 2018;68:203-8.

19. Luettel DM, Terluk MR, Roh J, Weinreb NJ, Kartha RV. Emerging biomarkers in Gaucher disease. In: Makowski GS, Editor. Advances in Clinical Chemistry. London UK, Elsevier; 2025. pp. 1-56.

20. Rosenbloom BE, Cappellini MD, Weinreb NJ, et al. Cancer risk and gammopathies in 2123 adults with Gaucher disease type 1 in the International Gaucher Group Gaucher Registry. Am J Hematol. 2022;97:1337-47.

21. Harvey AM, Barondess JA, Bordley J. Differential diagnosis: the interpretation of clinical evidence. 3th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1979. Available from: https://catalog.nlm.nih.gov/discovery/fulldisplay/alma995164033406676/01NLM_INST:01NLM_INST [accessed 22 December 2025].

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].