Management strategies for systemic lupus erythematosus using kinase inhibitors

Abstract

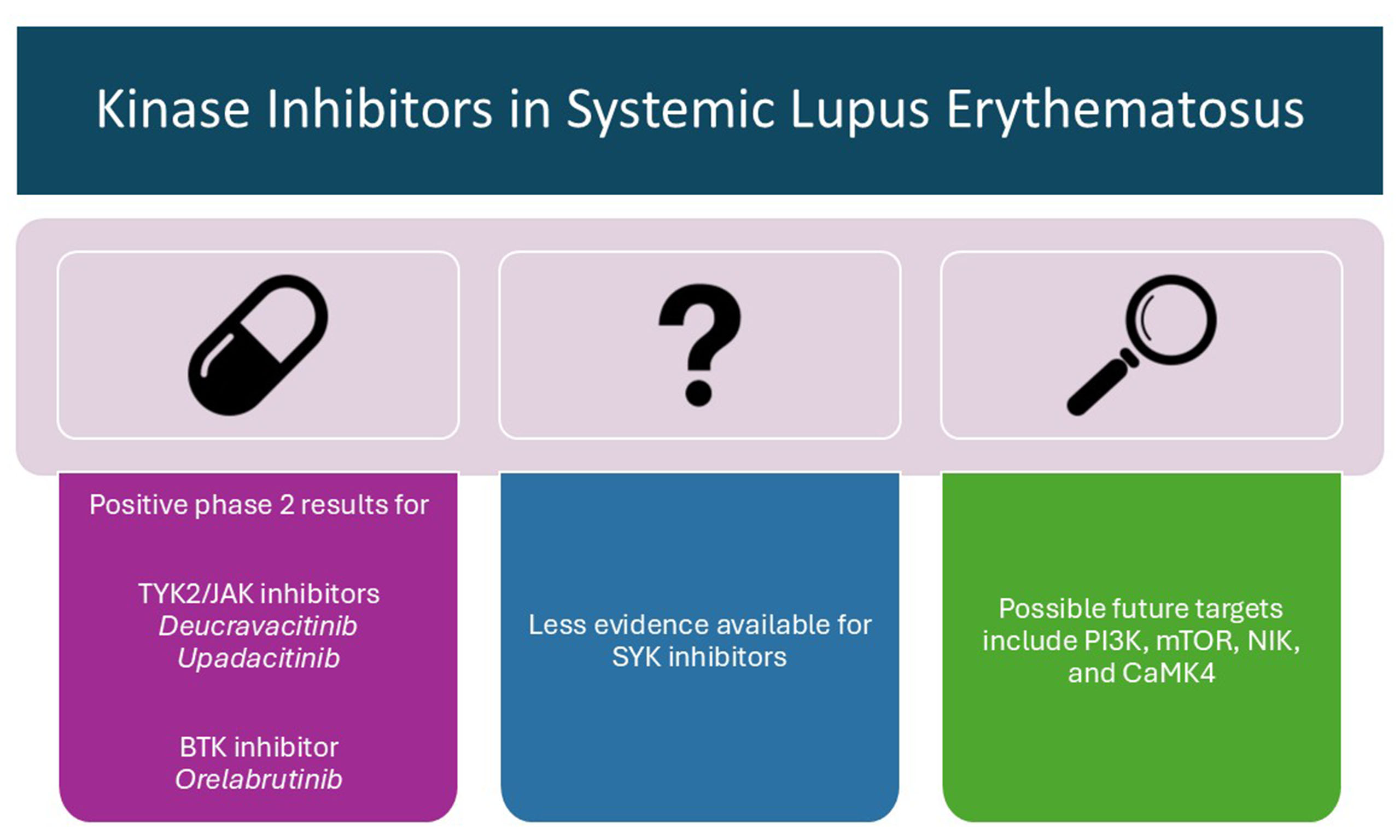

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, multisystem autoimmune disease that is undergoing a revolution in its treatment paradigm. Receptor kinases including Janus (JAK) kinases, Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK), and spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) are essential for signalling of many cytokines and receptors on immune cells. Suppression of these kinases changes the activation state of target cells, leading to inhibition of cytokine actions and effects such as autoantibody secretion. Therefore, therapeutic kinase inhibitors hold potential as treatments for SLE, but their efficacy and safety remain to be determined. Tyrosine kinase 2 and JAK inhibitors such as deucravacitinib and upadacitinib respectively have shown positive results in phase 2 trials, while further research into the JAK inhibitor baricitinib and BTK and SYK inhibitors has been less encouraging. This review summarises the current state of research on the use of kinase inhibitors in SLE.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Despite affecting more than 3.4 million people globally[1], available treatments for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are lacking compared to other autoimmune diseases with only one new therapy, anifrolumab, approved in the last decade[2]. Trials of many other therapeutic agents have failed to demonstrate superiority to placebo, likely due to the complexity of pathogenic pathways and diversity of biological and clinical phenotypes in SLE[3]. Apart from genetic factors and environmental triggers, multiple cytokines such as Type I interferons (IFNs), B cell activating factor (BAFF), and interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10 and IL-12 are believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of SLE[4]. Type I IFNs may be particularly important in altering B cell tolerance, leading to generation of autoantibodies that subsequently form immune complexes. With the exception of BAFF, the target of belimumab, targeting individual cytokines has never been effective in the treatment of SLE[5]. Anifrolumab targets the common IFN receptor and therefore inhibits the signalling of multiple Type I IFN proteins[2]. However, as all cytokines use pathways involving tyrosine kinases to transduce intracellular signals, targeting kinases holds potential as a more effective treatment for SLE by targeting upstream pathways. This review aims to summarise the current state of research on the use of kinase inhibitors in SLE.

KINASE INHIBITORS

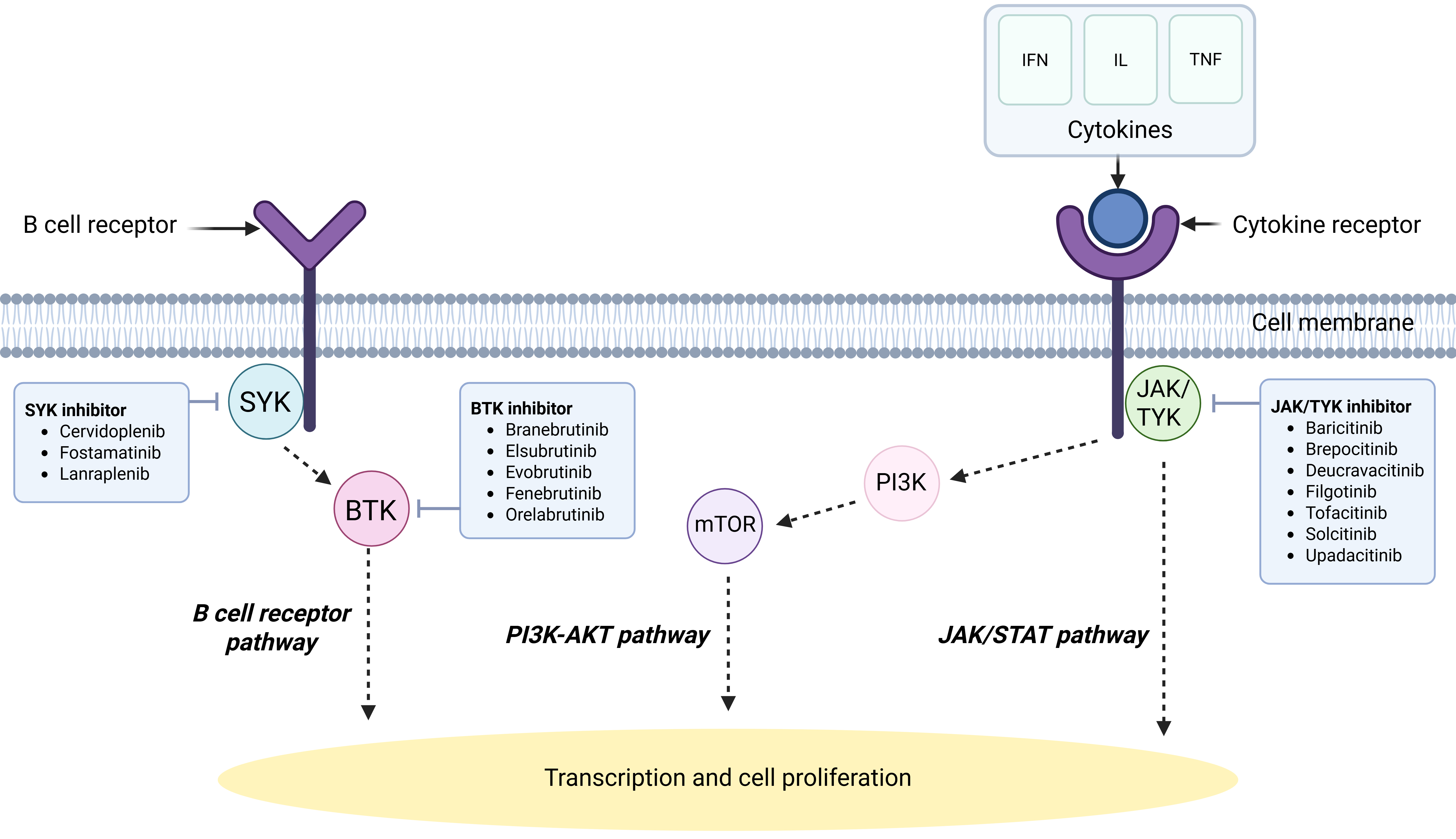

Tyrosine kinases transduce signals entrained by upstream stimuli, leading to downstream changes[6]. Depending on the stimulus, the effects transduced by these enzymes can include modifications in cell growth, migration, differentiation, apoptosis, or death. Activation or inhibition of these kinases can lead to dysregulated signalling cascades, resulting in autoimmune disease or malignancy[6]. They can be further classified into receptor tyrosine kinases, non-receptor tyrosine kinases, and dual-specificity kinases[6]. The non-receptor group comprises nine families: Abl, Ack, Csk, Fak, Fes/Fer, Jak, Src, Syk and Tec[6]. Potential targets in SLE pathogenesis include the Janus kinase (JAK) family - consisting of JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2)[7] - which is involved in signalling of multiple cytokines, as well as kinases involved in B cell receptor (BCR) signalling such as Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) and spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) [Figure 1], alongside lipid kinases such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)[8]. Inhibitors can potentially block the action of any tyrosine kinase to treat disease, and most kinase inhibitors are developed for oral administration, which improves patient adherence[6]. In addition, compared with biologics, receptor kinase inhibitors do not induce immunogenicity, resulting in a reduced risk of hypersensitivity or development of anti-drug antibodies and, in theory, higher chances of long-term efficacy[9].

Figure 1. A simplified diagram of signalling pathways implicated in SLE. Created in BioRender. L, K. (2025), https://BioRender.com/f49o466.

Janus kinase inhibitors

The JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway is a pivotal signalling pathway for cell function, and its dysregulation appears to be heavily implicated in the development of SLE[7]. While JAK3 is only expressed in the bone marrow, lymphatics, endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells, the other JAK family kinases JAK1, JAK2 and TYK2 are ubiquitously expressed in most tissues[7]. More than 50 cytokines and growth factors use components of the JAK/STAT pathway to signal, including Interferon alpha (IFNα), interferon gamma (IFNγ), IL-2, IL-6 and IL-12[10,11]. In each case, interaction between the ligand and its receptor causes transphosphorylation of the relevant JAK, after which active JAK induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the bound receptor, creating a docking site for STATs[10,11]. Subsequently, JAK proceeds to phosphorylate the relevant STAT, forming homodimers or heterodimers that translocate to the nucleus and act directly as transcription factors on target gene promoters in order to regulate transcription of target genes[10,11].

Currently, JAK inhibitors are approved for use in treatment of multiple inflammatory diseases, although not in SLE[12]. However, considerable evidence supports the potential utility of JAK inhibitors, including the observation that JAK/STAT pathways are a major mediator of signalling by Type I IFNs[13]. In murine models, treatment with JAK3 inhibitors significantly reduced proteinuria and improved renal function, and deposition of Complement component 3 (C3) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) was also significantly decreased in glomeruli[14]. JAK2 inhibition led to a reduction in several cytokines including IFNα, IL-12 and Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), as well as a reduction in serum C3 and glomerular infiltration[15]. JAK1 inhibition appeared to reverse severe proteinuria, reduce circulating double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibody levels, and lead to less extensive tubular damage[16]. Total, activated and central memory T cell numbers also decreased[16]. TYK2 has been shown to promote IFNα-induced autophagy in B cells[17]. Table 1 summarises the clinical trials of JAK/TYK2 inhibitors in SLE, and the results are detailed in the following section.

Clinical trials investigating the efficacy of JAK inhibitors in SLE (as of 11 September 2025). Source: http://clinicaltrials.gov

| Drugs | Target | Indication | Development stage | Primary endpoint | Trial identifier |

| Baricitinib | JAK1/2 | SLE | Phase 3 | Significantly greater proportion in baricitinib 4 mg group achieved SRI-4 compared to placebo | NCT03616912 |

| Phase 3 | No significant difference in SRI-4 responders compared to placebo | NCT03616964 | |||

| Brepocitinib | JAK1/TYK2 | SLE | Phase 2 | No significant difference in SRI-4 responders compared to placebo | NCT03845517 |

| Deucravacitinib | TYK2 | SLE | Phase 2 | Significantly greater proportion in deucravacitinib groups achieved SRI-4 compared to placebo | NCT03252587 |

| SLE | Phase 2 (results not yet published) | N/A | NCT03920267 | ||

| LN | Phase 2 (discontinued due to low enrollment) | N/A | NCT03943147 | ||

| SLE | Phase 3 (ongoing) | N/A | NCT05617677, NCT05620407 | ||

| Filgotinib | JAK1 | CLE | Phase 2 | No significant difference in CLASI-A score compared to placebo | NCT03134222 |

| LN | Phase 2 | Reduction of 24-h urine with filgotinib, but limited conclusions due to small number of patients | NCT03285711 | ||

| Tofacitinib | JAK1/3 | DLE/SLE | Phase 2 | Numerical improvement in CLASI-A score compared to placebo, but limited conclusions due to small number of patients | NCT03159936 |

| CLE | Phase 1/2 | Reduction in CLASI-A scores | NCT03288324 | ||

| Solcitinib | JAK1 | SLE | Phase 2 (terminated due to lack of efficacy) | No improvement in IFN transcriptional biomarker expression | NCT01777256 |

| Upadacitinib | JAK1 | SLE | Phase 2 | Significantly greater proportion of upadacitinib groups achieved SRI-4 and glucocorticoid dose ≤ 10 mg daily | NCT03978520 |

| SLE | Phase 3 (ongoing) | N/A | NCT05843643 |

Tofacitinib

Tofacitinib preferentially inhibits JAK1 and JAK3 with some effect on JAK2 and TYK2[7]. In murine models, tofacitinib has been shown to significantly decrease the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and reduce levels of anti-dsDNA antibodies and proteinuria, likely by reducing IFN signalling[18]. It also enhanced vascular function in murine lupus models through improving endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation, endothelial cell differentiation and lipoprotein profiles[18]. There are case reports where the use of tofacitinib resulted in improvement of interstitial lung disease and pericardial effusions secondary to SLE[19], as well as improvements in non-scarring alopecia due to SLE[20].

So far, three small studies have investigated tofacitinib in SLE. In a phase 1b trial, 30 patients were randomised to receive tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily or placebo (NCT02535689)[21]. Tofacitinib induced improvements in lipid profile, arterial stiffness, Type I IFN gene signature and circulating NETs[21]. These effects were more marked in patients with the Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 4 (STAT4) SLE risk allele[21]. Overall, tofacitinib was well tolerated, with no statistical differences in adverse events between the tofacitinib and placebo groups[21]. A small (n = 5), open-label, 24-week study of tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily showed an improvement in the Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index (CLASI) in patients with discoid lupus erythematosus (NCT03159936)[22]. A further open-label trial evaluated the effects of tofacitinib addition to background therapy for 72 weeks (NCT03288324), in which 73% of patients achieved a partial CLASI response of 6 points by week 4, and systemic features of disease activity as measured by Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) also improved significantly by week 24[23].

Baricitinib

Baricitinib is an oral inhibitor selectively targeting JAK1 and JAK2, and has been approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and some other autoimmune diseases[24]. A phase 2 study suggested that baricitinib at a dose of 4 mg could be an effective and well tolerated treatment for SLE, with a significant difference compared to placebo in the primary outcome measure[25]. A post hoc analysis of baricitinib effects on blood signatures indicated significant inhibitory effects on multiple pro-inflammatory pathways including the Type I IFN signature[26].

Subsequently, two phase 3 trials have been conducted[27,28]. In the first phase 3 trial, BRAVE-I, 760 patients with active SLE were randomised to receive baricitinib 4 mg daily, baricitinib 2 mg daily or placebo. BRAVE-I demonstrated that use of baricitinib 4 mg daily showed a higher SLE responder index (SRI)-4 rate when compared to placebo and the baricitinib 2 mg group[27]. However, the effectively identical BRAVE-II trial showed no difference in SRI-4 response at week 52 when compared with placebo[28]. In addition, neither phase 3 study demonstrated any significant differences compared to placebo in secondary endpoints, such as time to first severe flare and glucocorticoid tapering.

A few factors may have led to these conflicting results. SLE is a heterogeneous disease, although patient profiles in these studies were similar to those of recent phase 3 SLE clinical trials[28]. A post-hoc pooled analysis suggested that baricitinib may be efficacious in patients with higher disease activity (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) >

Brepocitinib

Brepocitinib is an inhibitor of JAK1 and TYK2[24]. One phase 2 trial has been conducted in patients with moderate to severe SLE, assessing the efficacy of brepoctinib versus placebo. (NCT03845517)[32] However, there were no significant differences in achievement of SRI-4 after 52 weeks when compared to placebo[32]. Analysis of British Isles Lupus Assessment Group-based Composite Lupus Assessment (BICLA) response also showed no differences[32]. It is unclear if the patient population at baseline had any significant differences in SLE disease activity or baseline treatment, as further results have not been published. Further trials have been discontinued and brepocitinib is now being developed for use in non-infectious uveitis and dermatomyositis.

Deucravacitinib

Deucravacitinib is an oral allosteric selective inhibitor of TYK2, which transduces signals from a family of cytokines distinct from the JAK kinases, namely Type I IFN, IL-10, IL-12, and IL-23[24]. A phase 2 trial has reported positive results in the treatment of moderate to severe SLE (NCT03252587)[33]. A total of 363 patients were randomised to receive deucravacitinib 3 mg twice daily, 6 mg twice daily, 12 mg once daily, or placebo[33]. Fifty-eight percent of the deucravacitinib 3 mg group achieved the primary outcome measure of an SRI-4 response at week 32, compared with 34% in the placebo group[33]. While the other treatment arms also achieved the primary endpoint, no added benefit was observed at higher deucravacitinib dosages[33]. All secondary endpoints such as Lupus Low Disease Activity State (LLDAS) response, 50% improvement in the Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index activity (CLASI-50) and change in joint counts were improved at week 48 in the 3 mg twice daily treatment groups when compared to placebo[33]. Deucravacitinib appeared to be well tolerated, with no statistically significant differences in adverse event rates compared with placebo at any of the doses tested[33]. Most common adverse events included upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, headache and urinary tract infections, which were mostly unrelated to treatment[33]. A phase 2 trial in lupus nephritis (NCT03943147) was terminated due to low enrolment, but phase 3 trials in SLE are ongoing (NCT05617677, NCT05620407).

Filgotinib

Filgotinib is a selective JAK1 inhibitor[24]. A phase 2 randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy of filgotinib 200 mg compared to a spleen kinase inhibitor, lanraplenib 30 mg, and placebo in moderate to severe cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) (NCT03134222)[34] (see separate section for lanraplenib results). A total of 45 patients were included in the study[34]. While filgotinib was generally well tolerated and showed a numerical improvement in Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index activity (CLASI-A) score at week 12 compared to both the lanraplenib and placebo groups, the primary endpoint was not met as the difference did not achieve statistical significance[34]. The most common adverse events were mild to moderate upper respiratory tract infection and headache[34].

Another phase 2 trial compared the use of filgotinib and lanraplenib in patients with lupus nephritis and membranous nephropathy (NCT03285711)[35]. However, limited conclusions could be drawn due to the small sample size of nine patients and lack of a placebo group[35]. Five patients received filgotinib, and there was a median reduction of 50.7% in 24-h urine protein at 16 weeks when compared to the lanrapelnib group which demonstrated a median reduction of 2.8%[35]. SLEDAI remained stable for both study arms at week 16[35]. Again, filgotinib appeared well tolerated with only 1 patient in the filgotinib group reporting an adverse event with grade ≥ 3[35]. Further study into the utility of filgotinib as a potential management option is required.

Upadacitinib

Upadacitinib is an oral agent with selectivity for JAK1, a kinase which modulates signalling by multiple cytokines including IFN, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-15. A 48-week phase 2 study evaluated the efficacy of upadacitinib and the BTK inhibitor elsubrutinib (see separate section) alone or in combination in 341 patients with moderate to severe SLE (NCT03978520)[36]. The study arms for elsubrutinib alone and low-dose combination therapy were discontinued early due to lack of efficacy, but positive outcomes were found in the remaining groups[36]. A higher proportion of patients on upadacitinib 30 mg daily, alone or in combination with elsubrutinib 60 mg daily, achieved the primary endpoint of SRI-4 response and glucocorticoid dose of

Solcitinib

Solcitinib is a selective JAK1 inhibitor[24]. A phase 2 randomised control trial in 50 non-renal SLE patients found that solcitinib lacked efficacy and was terminated prematurely, as determined by lack of improvement in IFN transcriptional biomarker expression (NCT01777256)[37]. In addition, there were four cases of liver function derangement and two cases of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms[37]. No further studies of solcitinib in SLE are planned.

Ruxolitinib

Ruxolitinib is a selective inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2[24]. While there is a paucity of ruxolitinib trials in SLE, evidence exists to suggest utility in CLE. In testing of mouse models prone to SLE and CLE, treatment with oral ruxolitinib resulted in reduction of severe skin lesions[38]. This effect may be due to the fact that ruxolitinib significantly reduces proteins such as C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9) and Myxovirus resistance protein A (MxA), overexpression of which is observed in SLE[39]. However, no differences were detected in other manifestations of systemic disease such as autoantibody production, immune complex deposition in the kidneys and renal disease[38]. Case reports have described topical ruxolitinib improving discoid lupus erythematosus and associated alopecia after two months of therapy[40]. Chilblain lupus erythematosus has also been reported to completely resolve after initiation of oral ruxolitinib[39]. Additionally, case reports have described ruxolitinib as a potential treatment for refractory hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to SLE[41]. Further studies on the use of ruxolitinib in CLE and SLE are required.

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors

While Bruton’s kinase pathway inhibition has shown success with treatment of other autoimmune conditions such as RA, immune thrombocytopenia and multiple sclerosis, BTK inhibitors have not shown a similar signal in SLE[42].

BTK is expressed in all myeloid cells and lymphocytes except T cells, natural killer (NK) cells and plasma cells, and is an intracellular non-receptor tyrosine kinase belonging to the Tec family[43]. It is involved in signal transduction of both Toll-like receptors (TLR) and the BCR, mediating the synergistic effects of TLR and BCR signalling on cytokine production[44]. Along with the innate immune system, B cell activation promotes production of autoantibodies, complement fixation and antigen presentation to T cells leading to production of cytokines and cytotoxic T cell activation[42]. B cell autoantibodies form immune complexes that deposit in the kidney, activating innate immune cells leading to cell damage and lupus nephritis[42]. The off-label use of anti-CD20 antibody rituximab to deplete mature B cells has been shown to be effective in the management of SLE and especially in refractory lupus nephritis[45]. Therefore, BTK is also a potential key target in mediating B cell activation[42]. Studies have shown that BTK expression in SLE patients correlates with fever, leukopenia, anti-dsDNA antibody and creatinine, with inverse correlation to estimated glomerular filtration rate[46]. Studies in murine models have also indicated that BTK inhibitors reduce B cell hyperactivity and significantly attenuate the SLE and lupus nephritis phenotype[47]. Despite this background, to date there has been limited success with the use of BTK inhibitors in SLE[42]. Five BTK inhibitors have been tested in phase 2 trials: branebrutinib, eslubrutinib, evobrutinib, fenebrutinib and orelabrutinib.

Some promise has been shown in a phase 2 trial of orelabrutinib, an irreversible BTK inhibitor, with preliminary results reported in abstract form only describing a SRI-4 response rate of 50%, 61.5% and 64.3% in patients treated with orelabrutinib at 50 mg, 80 mg and 100 mg, respectively, when compared to 35.7% in patients treated with placebo (NCT04305197)[48]. Treatment groups had reduced levels of proteinuria, anti-dsDNA, IgG and increased complement component 4 (C4)[48]. Notably, adverse events were also reported in 80%-100% of patient groups, though these were mostly mild to moderate[48].

In contrast, differences in SRI-4 response rates were not seen for fenebrutinib compared to placebo[49]. However, the reasons for the apparent lack of efficacy may be complex. After treatment with fenebrutinib, expected serological changes were observed, including reductions in anti-dsDNA and immunoglobulin levels, along with an increase in complement[49]. Post hoc analyses found that fenebrutinib treatment was associated with improved Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy - Fatigue (FACIT-F) scores compared to placebo, and enhanced efficacy was seen in patients with more active SLE at baseline, suggesting that certain patient subgroups may still derive some benefit[49]. However, murine models have previously demonstrated the overall effectiveness of BTK inhibitors in SLE, which has not been translated to these phase 2 trials[50,51]. Interestingly, Isenberg et al. noted a transient increase of peripheral CD19+ B cells at week 4, before seeing significant reductions at week 48, suggesting the key role of BTK in B cell activation and proliferation[49]. Therefore, another possible explanation to consider is the anergic B cells phenotype in SLE patients secondary to chronic autoantigen exposure, which would reduce responsiveness to BTK inhibition[52].

Evobrutinib also failed to demonstrate a meaningful difference in SRI-4 response compared to placebo[44]. In addition, there were no significant differences in annualised flare rate, Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), serum complete levels and anti-dsDNA levels[44]. Here, high doses of background glucocorticoids were noted across treatment arms, leading to high placebo response rates, with only 29%-34% of patients achieving a clinically meaningful reduction in glucocorticoid doses[44].

Elsubrutinib was studied both alone and in low- and high-dose combination therapy with JAK1 inhibitor upadacitinib (see separate section)[36]. The low-dose elsubrutinib arm was discontinued early due to lack of efficacy; however, while positive outcomes were found in the high-dose combination, these were similar to the effects of upadacitinib 30 mg daily alone, with no effect of elsubrutinib monotherapy and no additive effect[36].

Spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) inhibitors

SYK is primarily expressed in haemopoietic cells including B cells, immature T cells, macrophages and neutrophils[53]. It is a key component of the innate immune system, and binds to immune receptors such as BCR, Fc receptors (FcR) and C-type lectin receptors (CLR)[54,55]. SYK binds the associated adaptor proteins carrying immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMS) to activate downstream signalling, initiating degranulation of mast cells, cytokine release from macrophages and antigen recognition by B cells leading to antibody production[55]. Spleen tyrosine inhibitors target the abnormally high expression of SYK in T cells of patients with SLE[55]. In vitro studies have shown that correction of SYK levels results in normalisation in cell signalling and IL-2 production, leading to suppression of disease activity and even preventing disease in mouse models[56]. Despite success in in vitro models, there is a paucity of studies in this field, and the limited phase 2 trials have been less promising.

Lanraplenib is a selective SYK inhibitor[53]. In mouse models, it was shown to slow progression of lupus nephritis and reduce glomerular IgG deposition, as well as serum inflammatory cytokines[57]. As described above, in a phase 2 trial comparing the efficacy of lanraplenib versus filgotinib versus placebo (NCT03134222)[34], 19 out of 47 patients received lanraplenib[34]. While lanraplenib was well tolerated, the primary endpoint of change in CLASI-A at 12 weeks was not met[34]. In a separate study in lupus membranous nephritis, only four patients were enrolled and no conclusions regarding efficacy could be drawn; however, severe adverse events of coronary artery occlusion and hypersensitivity were reported in two patients who were both in the lanraplenib arm[35].

Fostamatinib is a SYK inhibitor that has been previously studied in phase 3 trials in RA. Although efficacy was observed, with significantly more patients achieving an American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20 response compared with placebo, adverse events such as hypertension, neutropenia, and elevated liver enzymes occurred in a dose-dependent manner, and further development as a therapy for RA was discontinued[58]. Fostamatinib is also approved for the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia, suggesting possible application in SLE[59]. In female lupus-prone mice, administration of fostamatinib before or after disease onset was shown to ameliorate skin and kidney disease, delay the onset of proteinuria and renal failure, and improve survival, without necessarily suppressing autoantibody titres[60]. A phase 2 trial in SLE was planned and initiated but withdrawn prior to enrolment of any patients (NCT00752999).

Cervidoplenib is another SYK inhibitor[53], studied only in murine models to date. Findings so far have demonstrated that administration of cervidoplenib at high doses significantly reduced splenomegaly and improved nephritis[61]. The mechanism behind this response is unclear, but it appears that B cells exposed to high-dose cervidoplenib expressed lower levels of BAFF receptors, and serum BAFF levels were also reduced[61].

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS

While data on the adverse effects of kinase inhibitors in SLE remain limited, their use in malignancies since the early 2000s demonstrates that kinase inhibitors are relatively safe[62]. Very few absolute contraindications have been identified, apart from pregnancy. A review of 396 women receiving first- or second-generation receptor kinase inhibitor therapy at the time of conception or in early pregnancy found that 51% of pregnancies were uneventful, 16% ended in spontaneous abortion, 4.3% resulted in pregnancy complications, and 5% resulted in a live birth with a congenital anomaly[63]. These observations are particularly relevant to SLE, as the majority of patients develop the disease during childbearing years. Adverse effects are seen less frequently in male patients[63], but JAK/STAT pathways play an important role in folliculogenesis[64]. Some case reports describe small numbers of female patients having uneventful pregnancies and deliveries after discontinuing kinase inhibitor therapy either six weeks before conception or at a gestational age of

Given the ubiquitous role of kinases in biology, toxicities can be broad and affect all organ systems[62]. Adverse effects are usually class-based and dose-dependent, and common adverse events include fatigue, fevers and gastrointestinal upset[6]. JAK inhibitor use is specifically associated with a higher risk of MACE, VTEs, gastrointestinal perforation, skin malignancy, and infections, with the most common and serious infections being pneumonia, nasopharyngitis, urinary tract infections, cellulitis, and herpes zoster[66].

Results from RA trials have previously reported a MACE hazard ratio of 1.2 for tofacitinib compared to a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor[67]. However, further results from a large RA cohort study comparing the risks of JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib and baricitinib) with adalimumab suggest that this concern is particularly relevant for patients over 65 years of age[66]. Hoisnard et al. found that risks of MACEs and VTEs are similar between JAK inhibitor and adalimumab use, including patients at high risk of cardiovascular diseases at baseline[66]. When analysing the subgroup of patients aged 65 years and older with at least one cardiovascular risk factor, the results were not statistically significant; however, the hazard ratio was 2.2, consistent with the initial findings from the Oral Rheumatoid Arthritis Trial Surveillance[66,67]. While the results are somewhat reassuring overall, these data suggest caution for this particular subgroup.

In addition, out of all the infectious complications, herpes zoster infection is the most common with JAK inhibitors[68]. Upadacitinib trials in RA have demonstrated higher rates of herpes zoster infections compared to patients on conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) and biologics[68]. However, in SLE, rates of herpes zoster infections in recent trials of belimumab (6.2%)[69] and anifrolumab (7.2%)[2] have been comparable. Overall, safety considerations for JAK inhibitor use should be individualised, and prescribers should ensure that patients receive a recombinant zoster vaccine, ideally prior to treatment initiation[70].

While BTK inhibitors also have increased risk of infections, cardiovascular adverse events including hypertension, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure and ventricular arrhythmias are additional concerns[71]. Newer BTK inhibitors, such as zanubrutinib and acalabrutinib, have been reported to cause fewer cardiovascular events; however, data are still limited, and there are no studies of these agents in SLE[71]. SYK inhibitors potentially have a more benign side effect profile, with no increase in risk of infection, but can lead to transient neutropenia and liver function derangement[72].

FUTURE KINASE INHIBITORS IN SLE

In addition to the above, there are also a multitude of other potential kinase targets for the treatment of SLE. The PI3K/protein kinase B (Akt) pathway has been implicated in angiogenesis, proliferation, cell survival, and inflammatory factor recruitment, and inhibition of this pathway has been shown to improve cancer survival as well as reduce inflammatory responses[73,74]. Importantly, PI3K signalling is implicated in B cell development, and activation of PI3K promotes the positive selection of B cells. Inappropriately high PI3K activity promotes production of autoantibodies, and limits class switching[75]. PI3K can be divided into three classes (I, II and III), and Class I is further divided into isoforms (PI3Kα, β, δ, γ), with PI3Kδ and PI3Kγ expressed preferentially in cells of the immune system[74]. Class I PI3K activation phosphorylates

Importantly, safety concerns have been noted in real-world use of PI3K inhibitors in cancer patients. Inhibition of PI3Kδ and PI3Kγ in murine models demonstrated reduced plasma cells, serum antibodies and reduced kidney antibody deposition[79]. Two PI3K inhibitors, idelalisib and umbralisib, have been approved for management of B cell malignancy[80,81], but both were subsequently withdrawn due to safety concerns, with signals for increased mortality. Further research is required to determine if these safety risks are a class issue.

mTOR is an atypical member of the PI3K-related kinase family which can be targeted for SLE treatment. After activation by Akt, mTOR plays a key role in the regulation of immune cells by forming two complexes: mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2)[73]. In murine models, targeted inhibition of the mTOR pathway with rapamycin led to significantly reduced albuminuria, anti-dsDNA levels and reduced interstitial leukocytic infiltration while increasing survival[82]. A small retrospective study of seven patients with lupus nephritis found that addition of mTOR inhibitors sirolimus or everolimus was associated with reduced proteinuria, improved serum creatinine and reduced dsDNA[83]. Following this, a phase 1 trial demonstrated a reduction of mean SLEDAI and mean total BILAG scores, with no new safety signals[84]. Targeting mTOR is likely to have some challenges, with the main consideration being mTORC2, which is resistant to rapamycin. Treatment with rapamycin alone will not result in full inhibition, and therefore mTORC2 will still be able to signal and stimulate the PI3K/Akt pathway[85]. Further research in SLE, along with exploration of combination therapies, may lead to new treatment options.

Another emerging target is nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB)-inducing kinase (NIK), which mediates activation of the canonical and non-canonical NF-κB pathways, leading to stimulation of downstream IL-1 and TNF receptors, including BAFF, TNF-related weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK), CD40 and OX40[86]. Studies have shown that NIK inhibition leads to reduced proteinuria, reduced gene expression and increased survival in murine lupus models[86].

Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV (CaMK4) is another potential target, as it is essential for T follicular cell expansion[87]. In mouse models, the absence of CaMK4 in T cells led to impairment of germinal centre formation, resulting in reduced anti-dsDNA titres, and glomerular IgG and complement deposition. Human T follicular cells also express CaMK4, and in vitro studies demonstrated that expression of BCL6 and IL21 was significantly downregulated after T follicular cells were cultured with a CaMK4 inhibitor for 48 h. There were no differences in CaMK4 expression between healthy donor cells and SLE patients, as SLE T follicular cells also showed a significant correlation between CaMK4 and BCL6 expression[87].

CONCLUSION

Therapeutic kinase inhibitors hold potential as treatments for SLE, but confirmation of their efficacy and safety requires further study. The failure of multiple single-cytokine targeting trials in SLE raises the possibility that targeting multiple pathways, such as those transduced by TYK2 and JAK family kinases, could provide broader benefit. The TYK2 and JAK1 inhibitors deucravacitinib and upadacitinib, respectively, have shown positive results in phase 2 trials in SLE, and phase 3 results are awaited, while phase 3 trials of baricitinib were inconclusive despite a positive phase 2 trial. In contrast, despite the clear role of B cells in SLE pathogenesis, findings with BTK and SYK inhibitors have been less encouraging. Further research into the potential of signalling kinase inhibitors in SLE is essential to determine whether their promise can be fulfilled.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content: Liao K, Lee HJ, Morand EF

All authors approved the final version for publication.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Morand EF reports speaker fees from Merck, Gilead, and Roche; and consulting fees and/or research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, DragonFly, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Galapagos, IgM, Genentech-Hoffman La Roche, Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Remegen, Takeda, and Union Chimique Belge. Liao K and Lee HJ declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Tian J, Zhang D, Yao X, Huang Y, Lu Q. Global epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comprehensive systematic analysis and modelling study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:351-6.

2. Morand EF, Furie R, Tanaka Y, et al. Trial of anifrolumab in active systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:211-21.

3. Moulton VR, Suarez-Fueyo A, Meidan E, Li H, Mizui M, Tsokos GC. Pathogenesis of human systemic lupus erythematosus: a cellular perspective. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23:615-35.

4. Crow MK. Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus: risks, mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:999-1014.

5. Dubey AK, Handu SS, Dubey S, Sharma P, Sharma KK, Ahmed QM. Belimumab: first targeted biological treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2011;2:317-9.

6. Thomson RJ, Moshirfar M, Ronquillo Y. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) Ineligible Companies, 2024. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03288324 [Last accessed on 19 Jan 2026].

7. Hu X, Li J, Fu M, Zhao X, Wang W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:402.

8. Cleary JM, Shapiro GI. Development of phosphoinositide-3 kinase pathway inhibitors for advanced cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12:87-94.

9. Favalli EG, Maioli G, Caporali R. Biologics or janus kinase inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis patients who are insufficient responders to conventional anti-rheumatic drugs. Drugs. 2024;84:877-94.

10. Tanaka Y, Luo Y, O'Shea JJ, Nakayamada S. Janus kinase-targeting therapies in rheumatology: a mechanisms-based approach. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18:133-45.

11. Alunno A, Padjen I, Fanouriakis A, Boumpas DT. Pathogenic and therapeutic relevance of JAK/STAT signaling in systemic lupus erythematosus: integration of distinct inflammatory pathways and the prospect of their inhibition with an oral agent. Cells. 2019;8:898.

12. Jamilloux Y, El Jammal T, Vuitton L, Gerfaud-Valentin M, Kerever S, Sève P. JAK inhibitors for the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18:102390.

13. Xue C, Yao Q, Gu X, et al. Evolving cognition of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway: autoimmune disorders and cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:204.

14. Ripoll È, de Ramon L, Draibe Bordignon J, et al. JAK3-STAT pathway blocking benefits in experimental lupus nephritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:134.

15. Lu LD, Stump KL, Wallace NH, et al. Depletion of autoreactive plasma cells and treatment of lupus nephritis in mice using CEP-33779, a novel, orally active, selective inhibitor of JAK2. J Immunol. 2011;187:3840-53.

16. Twomey RE, Perper SJ, Westmoreland SV, et al. Therapeutic JAK1 inhibition reverses lupus nephritis in a mouse model and demonstrates transcriptional changes consistent with human disease. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2024;6:900-11.

17. Dong G, You M, Fan H, Ding L, Sun L, Hou Y. STS-1 promotes IFN-α induced autophagy by activating the JAK1-STAT1 signaling pathway in B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:2377-88.

18. Furumoto Y, Smith CK, Blanco L, et al. Tofacitinib ameliorates murine lupus and its associated vascular dysfunction. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:148-60.

19. Li X, Luo K, Yang D, Hou C. A case report of systemic lupus erythematosus complicating interstitial lung disease and thickened pericardium treated with tofacitinib. Medicine. 2024;103:e39129.

20. Chen YL, Liu LX, Huang Q, Li XY, Hong XP, Liu DZ. Case report: reversal of long-standing refractory diffuse non-scarring alopecia due to systemic lupus erythematosus following treatment with tofacitinib. Front Immunol. 2021;12:654376.

21. Hasni SA, Gupta S, Davis M, et al. Phase 1 double-blind randomized safety trial of the Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3391.

22. Alsukait S, Learned C, Rosmarin D. Open-label phase 2 pilot study of oral tofacitinib in adult subjects with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:425-7.

23. Clinicaltrials.gov. Open-label study of tofacitinib for moderate to severe skin involvement in young adults with lupus. 2024. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03288324 [Last accessed on 28 Nov 2025].

24. Nakayamada S, Tanaka Y. Novel JAK inhibitors under investigation for systemic lupus erythematosus: - where are we now? Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2023;32:901-8.

25. Wallace DJ, Furie RA, Tanaka Y, et al. Baricitinib for systemic lupus erythematosus: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:222-31.

26. Dörner T, Tanaka Y, Petri MA, et al. Baricitinib-associated changes in global gene expression during a 24-week phase II clinical systemic lupus erythematosus trial implicates a mechanism of action through multiple immune-related pathways. Lupus Sci Med. 2020;7:e000424.

27. Morand EF, Vital EM, Petri M, et al. Baricitinib for systemic lupus erythematosus: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial (SLE-BRAVE-I). Lancet. 2023;401:1001-10.

28. Petri M, Bruce IN, Dörner T, et al. Baricitinib for systemic lupus erythematosus: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial (SLE-BRAVE-II). Lancet. 2023;401:1011-9.

29. Yin J, Hou Y, Wang C, Qin C. Clinical outcomes of baricitinib in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: Pooled analysis of SLE-BRAVE-I and SLE-BRAVE-II trials. PLoS One. 2025;20:e0320179.

30. Connelly K, Golder V, Kandane-Rathnayake R, Morand EF. Clinician-reported outcome measures in lupus trials: a problem worth solving. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e595-603.

31. Askanase AD, Vital EM, Meier O, et al. Evaluating the concordance between BICLA and SRI4 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus from the placebo arms of the EXPLORER and ATHOS trials. Lupus Sci Med. 2025;12:e001483.

32. Clinicaltrials.gov. A dose-ranging study to evaluate efficacy and safety of PF-06700841 in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). 2024. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03845517 [Last accessed on 28 Nov 2025].

33. Morand E, Pike M, Merrill JT, et al. Deucravacitinib, a tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor, in systemic lupus erythematosus: a phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023;75:242-52.

34. Werth VP, Fleischmann R, Robern M, et al. Filgotinib or lanraplenib in moderate to severe cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Rheumatology. 2022;61:2413-23.

35. Baker M, Chaichian Y, Genovese M, et al. Phase II, randomised, double-blind, multicentre study evaluating the safety and efficacy of filgotinib and lanraplenib in patients with lupus membranous nephropathy. RMD Open. 2020;6:e001490.

36. Merrill JT, Tanaka Y, D'Cruz D, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib or elsubrutinib alone or in combination for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a phase 2 randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024;76:1518-29.

37. Kahl L, Patel J, Layton M, et al. Safety, tolerability, efficacy and pharmacodynamics of the selective JAK1 inhibitor GSK2586184 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2016;25:1420-30.

38. Chan ES, Herlitz LC, Ali J. Ruxolitinib attenuates cutaneous lupus development in a mouse lupus model. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2338-9.

39. Klaeschen AS, Wolf D, Brossart P, Bieber T, Wenzel J. JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib inhibits the expression of cytokines characteristic of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26:728-30.

40. Park JJ, Little AJ, Vesely MD. Treatment of cutaneous lupus with topical ruxolitinib cream. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;28:133-5.

41. Jung JI, Kim JY, Kim MH, et al. Successful treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus with ruxolitinib: a case report. J Rheum Dis. 2024;31:125-9.

42. Ringheim GE, Wampole M, Oberoi K. Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors and autoimmune diseases: making sense of BTK inhibitor specificity profiles and recent clinical trial successes and failures. Front Immunol. 2021;12:662223.

43. Ding Q, Zhou Y, Feng Y, Sun L, Zhang T. Bruton's tyrosine kinase: a promising target for treating systemic lupus erythematosus. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;142:113040.

44. Wallace DJ, Dörner T, Pisetsky DS, et al. Efficacy and safety of the bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor evobrutinib in systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-ranging trial. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2023;5:38-48.

45. Tanaka Y, Nakayamada S, Yamaoka K, Ohmura K, Yasuda S. Rituximab in the real-world treatment of lupus nephritis: a retrospective cohort study in Japan. Mod Rheumatol. 2023;33:145-53.

46. Liao HT, Tung HY, Tsai CY, Chiang BL, Yu CL. Bruton's tyrosine kinase in systemic lupus erythematosus. Joint Bone Spine. 2020;87:670-2.

47. Kim YY, Park KT, Jang SY, et al. HM71224, a selective Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor, attenuates the development of murine lupus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:211.

48. Li R, Zhu X, Liu S, Zhang X, Xie C, Fu Z, et al. LB0005 orelabrutinib, an irreversible inhibitor of bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK), for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): results of a randomized, double-blinder, placebo-controlled, phase IB/IIA dose-finding study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:210.

49. Isenberg D, Furie R, Jones NS, et al. Efficacy, safety, and pharmacodynamic effects of the bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor fenebrutinib (GDC-0853) in systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:1835-46.

50. Mina-Osorio P, LaStant J, Keirstead N, et al. Suppression of glomerulonephritis in lupus-prone NZB × NZW mice by RN486, a selective inhibitor of Bruton's tyrosine kinase. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2380-91.

51. Chalmers SA, Wen J, Doerner J, et al. Highly selective inhibition of Bruton's tyrosine kinase attenuates skin and brain disease in murine lupus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:10.

52. Weißenberg SY, Szelinski F, Schrezenmeier E, et al. Identification and characterization of post-activated B cells in systemic autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2136.

53. Mok CC. Targeted small molecules for systemic lupus erythematosus: drugs in the pipeline. Drugs. 2023;83:479-96.

54. Mócsai A, Ruland J, Tybulewicz VL. The SYK tyrosine kinase: a crucial player in diverse biological functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:387-402.

55. Cooper N, Ghanima W, Hill QA, Nicolson PL, Markovtsov V, Kessler C. Recent advances in understanding spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) in human biology and disease, with a focus on fostamatinib. Platelets. 2023;34:2131751.

56. Grammatikos AP, Ghosh D, Devlin A, Kyttaris VC, Tsokos GC. Spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) regulates systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) T cell signaling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74550.

57. Pohlmeyer CW, Shang C, Han P, et al. Characterization of the mechanism of action of lanraplenib, a novel spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in models of lupus nephritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2021;5:15.

58. Tanaka Y, Millson D, Iwata S, Nakayamada S. Safety and efficacy of fostamatinib in rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate in phase II OSKIRA-ASIA-1 and OSKIRA-ASIA-1X study. Rheumatology. 2021;60:2884-95.

59. Bussel J, Arnold DM, Grossbard E, et al. Fostamatinib for the treatment of adult persistent and chronic immune thrombocytopenia: Results of two phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Hematol. 2018;93:921-30.

60. Deng GM, Liu L, Bahjat FR, Pine PR, Tsokos GC. Suppression of skin and kidney disease by inhibition of spleen tyrosine kinase in lupus-prone mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2086-92.

61. Cho S, Jang E, Yoon T, Hwang H, Youn J. A novel selective spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor SKI-O-703 (cevidoplenib) ameliorates lupus nephritis and serum-induced arthritis in murine models. Clin Exp Immunol. 2023;211:31-45.

62. Sunder S, Sharma UC, Pokharel S. Adverse effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy: pathophysiology, mechanisms and clinical management. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:262.

63. Rambhatla A, Strug MR, De Paredes JG, Cordoba Munoz MI, Thakur M. Fertility considerations in targeted biologic therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a review. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:1897-908.

64. Rosario R, Cui W, Anderson RA. Potential ovarian toxicity and infertility risk following targeted anti-cancer therapies. Reprod Fertil. 2022;3:R147-62.

65. Dou X, Qin Y, Huang X, Jiang Q. Planned pregnancy in female patients with chronic myeloid leukemia receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Oncologist. 2019;24:e1141-7.

66. Hoisnard L, Pina Vegas L, Dray-Spira R, Weill A, Zureik M, Sbidian E. Risk of major adverse cardiovascular and venous thromboembolism events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis exposed to JAK inhibitors versus adalimumab: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:182-8.

67. Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Connell CA. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1766-8.

68. Adas MA, Alveyn E, Cook E, Dey M, Galloway JB, Bechman K. The infection risks of JAK inhibition. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18:253-61.

69. Zhang F, Bae SC, Bass D, et al. A pivotal phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled study of belimumab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus located in China, Japan and South Korea. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:355-63.

70. Bass AR, Chakravarty E, Akl EA, et al. 2022 American college of rheumatology guideline for vaccinations in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Arthritis Care Res. 2023;75:449-64.

71. Awan FT, Addison D, Alfraih F, et al. International consensus statement on the management of cardiovascular risk of Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors in CLL. Blood Adv. 2022;6:5516-25.

72. Weinblatt ME, Kavanaugh A, Genovese MC, Musser TK, Grossbard EB, Magilavy DB. An oral spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1303-12.

73. He Y, Sun MM, Zhang GG, et al. Targeting PI3K/Akt signal transduction for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:425.

74. Hawkins PT, Stephens LR. PI3K signalling in inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1851:882-97.

75. Omori SA, Cato MH, Anzelon-Mills A, et al. Regulation of class-switch recombination and plasma cell differentiation by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling. Immunity. 2006;25:545-57.

76. Bacalao MA, Satterthwaite AB. Recent advances in lupus B cell biology: PI3K, IFNγ, and chromatin. Front Immunol. 2020;11:615673.

77. O'Neill SK, Getahun A, Gauld SB, et al. Monophosphorylation of CD79a and CD79b ITAM motifs initiates a SHIP-1 phosphatase-mediated inhibitory signaling cascade required for B cell anergy. Immunity. 2011;35:746-56.

78. Wu XN, Ye YX, Niu JW, et al. Defective PTEN regulation contributes to B cell hyperresponsiveness in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:246ra99.

79. Olayinka-Adefemi F, Hou S, Marshall AJ. Dual inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinases delta and gamma reduces chronic B cell activation and autoantibody production in a mouse model of lupus. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1115244.

80. Gopal AK, Kahl BS, de Vos S, et al. PI3Kδ inhibition by idelalisib in patients with relapsed indolent lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1008-18.

81. Gribben JG, Jurczak W, Jacobs RW, et al. Umbralisib plus ublituximab (U2) Is superior to obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil (O+Chl) in patients with treatment naïve (TN) and relapsed/refractory (R/R) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): results from the phase 3 Unity-CLL study. Blood. 2020;136:37-9.

82. Lui SL, Tsang R, Chan KW, et al. Rapamycin attenuates the severity of established nephritis in lupus-prone NZB/W F1 mice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:2768-76.

83. Yap DY, Ma MK, Tang CS, Chan TM. Proliferation signal inhibitors in the treatment of lupus nephritis: preliminary experience. Nephrology. 2012;17:676-80.

84. Lai ZW, Kelly R, Winans T, et al. Sirolimus in patients with clinically active systemic lupus erythematosus resistant to, or intolerant of, conventional medications: a single-arm, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1186-96.

85. Michailidou D, Gartshteyn Y, Askanase AD, Perl A. The role of mTOR signaling pathway in systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2025;24:103910.

86. Brightbill HD, Suto E, Blaquiere N, et al. NF-κB inducing kinase is a therapeutic target for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Commun. 2018;9:179.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].