The inflammatory pathogenetic pathways of Fabry nephropathy

Abstract

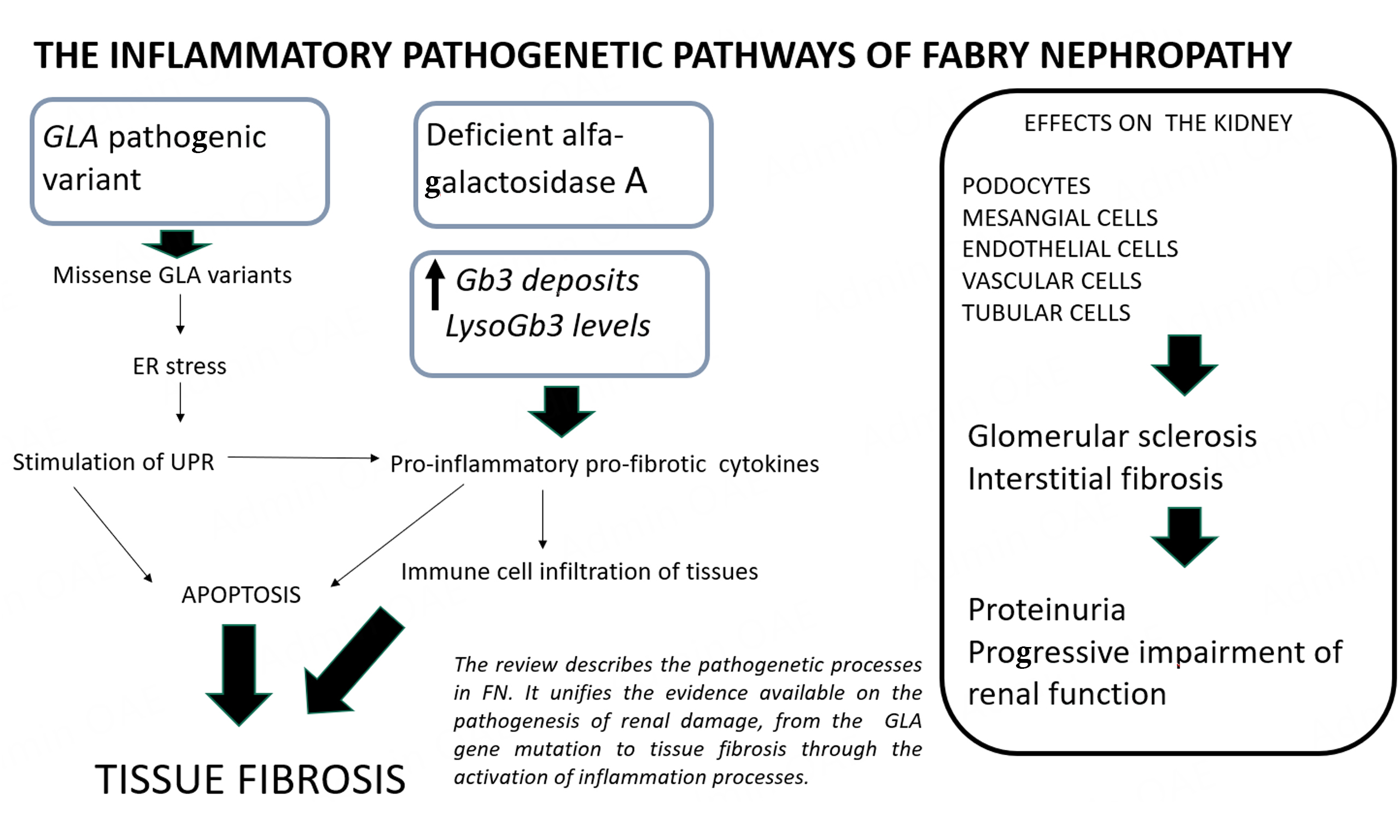

The high variability in clinical features and outcomes observed in monogenic diseases such as Fabry disease suggests the presence of additional pathogenetic pathways beyond the lysosomal deposition of globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) and globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3). Research indicates that the deposition of Gb3 and lyso-Gb3 can stimulate inflammatory processes. Immune-competent mononuclear cells exposed to Gb3 deposition exhibit surface adhesion molecules and release pro-inflammatory and fibrotic cytokines such as interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and transforming growth factor-β. This culminates in the activation of inflammatory cascades associated with oxidative stress and apoptotic mechanisms maintained by renal resident and infiltrating cells, leading to chronic inflammation and tissue fibrosis. Furthermore, from another angle (termed Agalopathy), the mutated galactosidase alpha gene can result in the production of an altered alpha-galactosidase A enzyme, inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress and triggering the unfolded protein response (UPR) in an effort to prevent the production of altered proteins. The UPR, in turn, instigates the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby contributing to the inflammatory milieu. Experimental findings have demonstrated that the pathogenetic mechanisms activated by the deposition of Gb3 and lyso-Gb3 can become independent of the initial stimulus and may exhibit limited responsiveness to therapy. Cellular pathway alterations can persist post-therapy or after gene correction. Moreover, biochemical and histological lesions characteristic of Fabry disease manifest in the absence of Gb3 in the zebrafish experimental model. This review endeavors to describe the role of these processes in Fabry nephropathy and aims to summarize the available evidence on the pathogenesis of renal damage.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Renal involvement is a significant factor in Fabry disease, influencing patient outcomes considerably, and it was the primary cause of death in Fabry patients prior to the availability of enzyme replacement therapy [ERT][1]. The clinical course of Fabry nephropathy [FN] is variable. In males with the classical phenotype, urinary concentration defects may manifest at a young age during the initial phase and are often overlooked. Over time, mild proteinuria develops, followed by arterial hypertension and progressive impairment of renal function. The nephropathy follows a progressive, chronic course, with overt renal failure typically appearing in the third or fourth decade of life, potentially necessitating dialysis treatment. For eligible patients, renal transplant stands as a viable option, often yielding successful outcomes. Conversely, the renal clinical course tends to be less aggressive in females and in patients with late-onset variants, where nephropathy occurs later in life. Typically, these phenotypes exhibit mild renal manifestations for a long time, with the diagnosis of Fabry disease often delayed for many years or coincidentally made during a screening program[2].

Fabry disease is an X-linked monogenic disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the galactosidase alpha (GLA) gene that encodes the lysosomal enzyme α-galactosidase A. The deficient activity of α-galactosidase A causes a progressive lysosomal deposition of the glycosphingolipids globotriaosylceramide [Gb3] and its derivative globotriaosylsphingosine [lyso-Gb3].

Even though only one gene is involved in the pathogenesis of the disease, the clinical presentation among Fabry patients is highly heterogeneous. Affected members from the same family with the same GLA mutation and with classical or late onset can present a broad spectrum of phenotypes[3]. Consequently, over the years, it has become more evident that the progressive deposition of Gb3 could not fully explain the pathogenic mechanisms occurring in tissues and organs. Thus, it has been hypothesized that additional pathogenetic pathways could play a role in tissue damage[4].

Many studies have been undertaken to understand these processes, and the molecular and cellular pathogenetic mechanisms triggered by GLA mutations and lysosomal Gb3 deposition have drawn significant attention from researchers. Among the altered pathways, a subtle and chronic inflammation due to exposure to Gb3/lyso-Gb3, resulting in tissue fibrosis, has been extensively described[5,6]. This review reports these studies with particular emphasis on the pathogenic development of FN.

EVIDENCE ON THE ROLE OF INFLAMMATION AND THE IMMUNE RESPONSE

Lysosomal deposits may act as damage-associated molecular patterns [DAMPs] or cause DAMP production by injured cells. The presence of DAMPs is sensed by pattern recognition receptors in innate immune cells, leading to pro-inflammatory activity that results in cytokine secretion and apoptosis[7]. The released cytokines interact with leukocytes, resulting in perturbations in the proportions of leukocyte subsets in peripheral blood from patients, and these cells display high surface expression of adhesion molecules[8]. The first pieces of evidence on the presence of chronic activation of inflammation associated with Fabry disease came from studies on mononuclear cells from patients, which showed constitutive overproduction of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)[9,10]. When exposed to high levels of Gb3, normal dendritic cells and macrophages produce pro-inflammatory cytokines[9]. This immune response was shown to be mediated by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) ligation.

Associated with this pro-inflammatory environment, mononuclear cells from naïve Fabry patients displayed a higher apoptotic state, which was lower in patients undergoing ERT. Adding Gb3 to normal cells induces apoptosis mediated by the intrinsic pathway, in which altered mitochondria play a role[11]. Furthermore, neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein and apoptosis-inducing factor were found to be differentially expressed among Fabry patients[12].

Inflammatory pathway activation is also manifested by the presence of complement-activated components C3 (complement component 3) and iC3b (an inactivated form of C3b) in the GLA knockout (GLA-KO) mouse model[13] and in the serum, plasma, and brain of patients with Fabry disease[14].

Target organs in Fabry disease, namely the nervous system, kidney, and heart, suffer from infiltration with immune cells that are recruited in an attempt to mitigate and heal the harmful effects of lysosomal deposits. Nervous system involvement is characterized by the recruitment of immune cells, associated with activating microglia, natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells in central and peripheral nervous tissues[15]. Immune infiltration of T cells and macrophages is also observed in cardiac and renal tissues[6,16].

Tubular cells collected from urine samples of Fabry patients revealed impairment of mitochondrial morphology and increased oxygen consumption rate, reflecting mitochondrial dysfunction[17]. These alterations increase autophagy, causing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and proapoptotic signaling[18]. These findings suggest that mitochondrial dysfunction can contribute to inflammation pathways and renal damage.

Overall, data from experimental models and human investigations in Fabry disease are consistent. The interaction between Gb3 and immunocompetent cells causes a subtle, chronic, and insidious activation of the innate immunity and associated processes, resulting in overlooked inflammation. Acute inflammation is a physiological response aimed at eliminating damage in cells or tissues. However, if, as in Fabry disease, the damage cannot be eliminated, inflammation becomes chronically stimulated due to continuous production of glycolipid deposits. Chronic inflammation induces the formation of a scar in which normal parenchyma is replaced by fibrotic tissue, leading to loss of organ function[19].

GLA GENE AND ENDOPLASMIC RETICULUM STRESS: THE ROLE OF THE UNFOLDED PROTEIN RESPONSE

In an effort to elucidate the pathophysiology of organ involvement in Fabry disease patients, the pathogenic role of endoplasmic reticulum [ER] stress and the unfolded protein response [UPR] emerged as a possible hypothesis. The ER physiologically checks the correct folding of proteins before releasing them and either repairs or retains those with altered structures. Many Fabry disease pathogenic variants are missense, and mutated proteins are misfolded and retained in the ER instead of being transported to the lysosome[20]. High ER retention of misfolded proteins leads to ER stress that, if maintained, results in the activation of the UPR. The UPR is a sophisticated collection of intracellular signaling pathways that have evolved to respond to protein misfolding in the ER. In addition, it has become increasingly clear that UPR signaling is essential for immunity and inflammation[21]. There is a reciprocal regulation between ER stress and inflammation, whereby ER stress can activate inflammatory pathways, and, in turn, pro-inflammatory stimuli can trigger ER stress, such that the resulting UPR activation can further amplify inflammatory responses[22]. UPR activation in immune cells and various stromal cells induces the secretion of cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF. Conversely, cytokines themselves can directly regulate the UPR[23].

Apoptotic cell death mediated by UPR is carried out by the initiator caspases 12 and 4. A study on mononuclear cells from Fabry patients revealed higher levels of caspase 12 but variable results with caspase 4. Further investigation showed no differences in the expression levels of ER stress-associated genes, ruling out ER stress involvement in apoptotic cell death in mononuclear cells from Fabry patients[11].

Further studies using other cells or animal models showed different potential effects of excess misfolded GLA proteins in the ER. A GLA-KO HEK293 cell line model induced by transient transfection and expression of mutated GLA proteins caused ER stress and UPR activation[24]. Responses to ER stress and the UPR may be cell type-dependent, implying that not all cell lines or tissues respond equally to an excess of misfolded proteins[25]. This means that pathogenic mechanisms associated with the UPR could be tissue-dependent.

In a fly model, expression of GLA variants resulted in ER retention, ER-associated degradation, and UPR activation, which was improved by the pharmacological chaperone migalastat[26]. Interestingly, further research in flies showed that UPR activation resulted in the death of dopaminergic cells and a shorter life span.

Nikolaenko et al. recently highlighted another facet of ER stress, which is not directly associated with misfolded GLA due to changes in its primary sequence but with exposure to high lyso-Gb3 levels. Evidence from a proteomic study revealed that exposure to lyso-Gb3 affected protein folding and ubiquitination pathways. High lyso-Gb3 levels may cause direct disruption of the chaperone system in the cytosol and in the ER, increasing ubiquitination[27].

The role of ER stress and the UPR may suggest that Fabry disease is not only a storage disease but also has a gain-of-function component due to ER retention of mutant protein and ER stress caused by an excess of accumulated glycolipids.

THE GLOMERULAR AND VASCULAR COMPARTMENT

Upon routine histochemical observation of glomeruli from Fabry disease kidney biopsies, Gb3 deposits appear as empty vacuoles in the cytoplasm of all cells, prominently in podocytes. Usually, mesangial areas are enlarged with an increase in the extracellular matrix and a proliferation of the mesangial cells. Moreover, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is typically present due to podocyte damage. Over time, these lesions result in diffuse global glomerular sclerosis, and clinically the changes translate into proteinuria and progressive impairment of renal function with an overt chronic renal disease[28].

The podocyte has been extensively investigated in FN. Sanchez-Niño demonstrated that upon exposure of human podocytes in vitro to increasing concentrations of lyso-Gb3, these cells release inflammatory mediators of glomerular damage, such as transforming growth factor-β [TGF-β]. TGF-β is a powerful activator of collagen and fibronectin synthesis and determines an increase in extracellular matrix production and tissue fibrosis[29]. Later, Sanchez-Niño demonstrated that Gb3 increases the Notch-1 signaling, a podocyte injury mediator, with nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation. NF-κB is the trigger that stimulates the release of pro-inflammatory and profibrotic cytokines[30]. The deposition of Gb3 in podocytes causes progressive injury and podocyte detachment into urine, so-called podocyturia[31]. The podocyte has limited or no turnover, and its loss is associated with segments of denuded glomerular basement membrane, changes in the slit diaphragm, and subsequent areas of segmental glomerular sclerosis.

Mesangial cells proliferate, accompanied by an increase in mesangial extracellular matrix. Indeed, these cells, under Gb3 deposition, release pro-inflammatory and profibrotic cytokines[32]. Mesangial cells express the plasma membrane TLR4[33] that, following the recognition of Gb3, start the innate immune response with the release of cytokines[9]. Moreover, the mesangium is colonized by inflammatory circulating cells such as myofibroblasts, macrophages, and monocytes, stimulating local inflammation by releasing IL-1β and TNF-α[33]. Proteomic studies have found many signs of tissue inflammation in the urine of Fabry patients, including high levels of uromodulin, prostaglandins, podocalyxin, and fibroblast growth factor 23, and ERT is associated with a reduction in the urinary levels of these molecules[34,35].

The glomerular capillaries can be considered highly differentiated vascular structures, and the endothelium is a target of Gb3 deposition. Exposure to Gb3 triggers oxidative stress and overexpression of adhesion molecules, and it is associated with the oxidation of many molecules, such as DNA, lipids, and proteins, resulting in cellular dysfunction[36]. Moreover, Gb3 causes the deregulation of many endothelial pathways, such as endothelial nitric oxide synthase [eNOS], with decreased nitric oxide bioavailability or enzyme uncoupling, and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines mediated by cyclooxygenase[37]. In larger vessels, lyso-Gb3 also induces the proliferation of smooth muscle cells that, in addition to the oxidative processes, causes a thickening of the vascular wall and indirectly complications of ischemia[38].

Finally, an imbalance between molecules inhibiting neovascularization [thrombospondin-1], fibroblast growth factor, and proangiogenic elements [eNOS, angiopoietin2] was described in Fabry patients, highlighting the role of vascular structures in FN[39].

THE INFLAMMATORY PROCESSES AND THE TUBULE-INTERSTITIAL RESPONSE

The tubular interstitium has a pathogenic role in FN, although the related clinical signs are mild[40]. Akin to all kidney cell types, tubular cells are affected by exposure to glycolipid deposits[41]. They are dividing cells with a high metabolic expenditure and energy consumption, and one of the cell types with the highest number of mitochondria per cell in the body[42].

In vitro studies with tubular cell lines showed mitochondrial dysfunction[17], increased autophagy and ROS production, as well as proapoptotic signaling[18]. As the tubular system of the kidney is highly dependent on mitochondrial function to uphold the transcellular transport of solutes and active secretion of compounds into the urine, dysfunction of the central energy metabolism can result in harmful effects. Moreover, in vitro exposure of the epithelial tubular cell line HK2 to Gb3 and lyso-Gb3 resulted in transdifferentiation to myofibroblasts displaying a profibrotic profile[43].

The contribution of the tubular compartment to pathogenesis could also be deduced from studies with mouse models. Observations in the mouse model developed by cross-breeding the GLA-KO with the Gb3 synthase transgenic mice [GLA-KO-Tg][44] revealed tubular glycolipid injury that affects renal function, with polyuria, polydipsia, and decreased urine osmolality, but without remarkable glomerular damage[45].

Studies on renal biopsies from human Fabry patients have stressed the importance of the tubular system in the pathogenesis of the disease. The main profibrotic cytokine, TGF-β, is produced by proximal tubular cells[6]. This profibrotic environment induces transdifferentiation of epithelial cells into fibroblasts that were shown to be present in pericytes surrounding peritubular capillaries, mesangial cells, and the periglomerular zone. Therefore, tubular cells could be the cells in which pathological profibrotic changes are initiated. This insult then spreads to other renal areas, leading to fibrotic deposition in the glomerulus and the interstitium[30]. In a recent study, Turkmen et al. analyzed the subpopulations of infiltrating immune cells in renal biopsies from a small group of Fabry patients at baseline and under ERT[46]. This study revealed a reduction in CD8+, CD16+, T cells, and NK cells and an increase in CD20+ B cells and CD38+ plasma cells, indicating the active participation of interstitial infiltrating immune cells in the inflammation and the subsequent renal damage.

THE ROLE OF THERAPY IN MODULATING THE PATHOGENIC MECHANISMS

ERT with two molecules, agalsidase alpha and beta, has been available for Fabry disease for twenty years. Recently, oral treatment with a chaperone of alpha-galactosidase A [migalastat] has also been prescribed for patients carrying amenable mutations. Migalastat binds to and stabilizes the mutated enzyme and increases its lysosomal trafficking and enzyme activity. These therapies have undoubtedly changed the outcomes of Fabry patients, stopping or slowing down the progression of the disease. Notably, the scientific community agrees on two points: the best results are obtained in patients who start therapy early, and late treatment does not have the same efficacy as early treatment[2,47].

Gene therapy for Fabry disease is still being carried out in a few centers and represents an innovative solution. In Canada, five patients were treated with lentivirus-mediated gene therapy. After 3-5 years, there is persistent polyclonal engraftment with plasma and leukocyte GLA activity above baseline, with a fall in Gb3 and lyso-Gb3 levels[48]. However, these procedures are expensive and not consistently successful, and some trials have been stopped.

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors [SGLT2i], drugs blocking tubular glucose reabsorption, have demonstrated their efficacy in reducing the progression of renal damage in nephropathies and cardiovascular mortality. SGLT2i works indirectly by interfering with the glomerular-tubular balance and increasing tubular urinary flux. Most relevant studies were conducted on diabetic nephropathy in chronic renal disease, immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy, and FSGS. Recently, SGLT2i has been proposed as a therapy for Fabry nephropathy, and a study is ongoing[49].

During the last few years, several pieces of evidence have been presented that substantially explain the different results obtained depending on the therapy timing. Braun et al. studied human podocyte cultures with reduced alpha-galactosidase A activity[50]. These podocytes presented Gb3 deposition, displayed dysfunction of autophagic mechanisms, and released a panel of profibrotic cytokines. Upon addition of recombinant alpha-galactosidase A, these podocytes showed complete clearance of Gb3; however, glycolipid clearance was not associated with the correction of the altered cytokine signaling pathways. The authors suggest that a point of no return could exist, after which the alpha-galactosidase A cannot fully correct cellular dysfunction despite eliminating Gb3.

Jehn et al. studied the altered cellular pathways in podocytes, endothelial cells, and urinary-derived cells from patients using proteomics analysis[51]. GLA-deficient cells displayed dysregulated levels in proteins involved in lysosomal traffic, cell-cell interactions, and other activities that were partially restored by a rescue with inducible GLA introduced using a sophisticated technique involving lentiviruses [clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/associated protein-9 nuclease (Cas9)-mediated GLA]. These results proved that a deficiency of GLA activity elicits severe changes in physiological pathways in all kinds of cells, and the therapy cannot completely restore physiological functions.

Recently, Braun et al. published a paper confirming that ERT alleviates lysosomal dysfunction but cannot always reverse organ damage[52]. The therapy reduced Gb3 accumulation in podocytes in renal biopsies from Fabry patients, but notably, the foot-processes effacement persisted in some tracts. A CRISPR/CAS9-mediated alpha-galactosidase knockout podocyte cell line confirmed the ability of ERT to clear cellular Gb3 deposition without resolving lysosomal dysfunction. Finally, a transcriptomic investigation identified alpha-synuclein [SNCA] as a mediator of lysosomal dysfunction. SNCA is a protein that regulates synaptic vesicle trafficking and subsequent neurotransmitter release. It has been implicated in other lysosomal diseases and is well-known for its role in Parkinson's disease. SNCA is negatively associated with decreased enzymatic degradation and could mediate resistance to ERT[53]. Inhibition of SNCA, both genetic and pharmacological [by β2 adrenergic receptor agonists], significantly improves lysosomal structure and dysfunction. Therefore, only with SNCA correction can ERT reach the target to correct the GLA defect.

All these experimental pieces of evidence share a mechanism by which the deposition of Gb3 is followed by dysregulation of pathogenetic pathways, resulting in severe cellular injury. The ERT can clear the cells of Gb3 deposition but has limited effects on the dysregulated pathways. Therefore, an early start of treatment can halt or reduce the Gb3 deposition and the activation of pathological pathways such as progressive inflammation. Late therapy has a reduced effect because these dysregulated mechanisms, from a certain point onwards, become independent of Gb3 activation.

A COMPREHENSIVE IDEA ABOUT Gb3 DEPOSITION, INFLAMMATION, FIBROSIS, AND PROGRESSION OF RENAL DAMAGE

The pathogenesis of tissue damage in Fabry disease in general and in FN in particular is very complex and still unclear. Undoubtedly, the deposition of Gb3 alone cannot explain the variability of clinical cases and the different rates of disease progression. Over the past few years, we have gathered much evidence that reveals exciting and complex pathogenetic pathways.

We propose that a gene mutation already determines changes in biological processes in the physiological activity of the ER with hyperactivation of the UPR [Figure 1]. This UPR is subsequently associated with stimulated inflammation, as described in other diseases such as cancer and diabetes[22]. In this case, we could define this as a pathology of the gene, so-called Agalopathy. In support of this hypothesis, we must consider the GLA-mutant zebrafish experimental model. This model displays the same functional mitochondrial alterations and structural changes in FN, but lacks Gb3 synthetase, and therefore, there is no Gb3 lysosomal deposition[54].

Figure 1. The molecular pathogenetic mechanisms causing renal damage in Fabry nephropathy. The GLA mutation causes the synthesis of altered proteins with stimulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress. The unfolded protein response determines the release of inflammatory cytokines and increases apoptosis (light blue boxes). The GLA mutation also causes the lysosomal deposition of Gb3/lyso-Gb3 with derangement of lysosomal functions and release of cytokines (pink boxes). The Gb3/lyso-Gb3 deposition can stimulate the new cellular protein synthesis, activating the Notch-1/NF-κB pathway and releasing pro-inflammatory and profibrotic cytokines (green boxes). All these pathways are interconnected, and the final result is the inflammation and fibrosis of the kidney. Gb3: globotriaosylceramide; lyso-Gb3: globotriaosylsphingosine; Notch-1: notch receptor 1 (human); NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa B.

The lysosomes are the site of severe engulfment due to Gb3 deposition interfering with normal lysosome functions, and dysregulation of physiological processes, such as autophagy, occurs. In particular, engulfed podocytes detach from the glomerular basement membrane, and glomerular segmental sclerosis becomes apparent using light microscopy[28].

Moreover, Gb3 deposition causes activation of inflammation through the interaction with Notch-1 and NF-κB, resulting in the recruitment of leukocytes to the glomeruli, exacerbating the status. Inflammatory activation causes a chronic insult to the cells and tissues that causes cellular dedifferentiation with activation of extracellular matrix protein synthesis and release of cytokines with inflammatory (IL-1β) or profibrotic (TGF-β) roles. In the kidney, the mesangial cells produce an excess of extracellular matrix, while metalloproteinases have reduced removal activity. All these processes can eventually become independent of the initial Gb3 deposition, resulting in progressive renal tissue inflammation and fibrosis[30]. Kidney fibrosis is an irreversible process resulting in progressive loss of renal function and scar tissue development.

CONCLUSIONS

Evidence in the literature demonstrates that the deposition of Gb3 is associated with alterations in the immune response and with subtle covert processes of inflammation primarily mediated by innate immune mechanisms. All the evidence of activation of inflammatory mechanisms (Gb3 deposition, cytokine release, UPR, etc.) could explain the variability of the clinical picture in the same family: the individual biological response to Gb3 deposition depends on numerous and complex variables. Furthermore, it is reasonable to speculate that early therapy could interfere with and reduce cellular reactions to Gb3 while late treatment could limitedly prevent the progression of FN.

DECLARATIONS

Authors' contribution

Closely designed the review and finalized the manuscript, contributed comprehensive ideas about Gb3, inflammation, fibrosis, the progression of renal damage, and conclusions: Feriozzi S, Rozenfeld P

Wrote the introduction, and sections on the glomerular and vascular compartments, as well as the role of therapy in modulating pathogenetic mechanisms: Feriozzi S

Wrote sections on the role of inflammatory processes and the immune response, the GLA gene and endoplasmic reticulum stress, including the unfolded protein response, the inflammatory processes, and the tubule-interstitial response: Rozenfeld P

Availability of data and materials

This manuscript is a review, and all data supporting the text have been officially published in the literature. All papers consulted for the text are quoted in the References.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2024.

REFERENCES

1. Mehta A, Beck M, Elliott P, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy with agalsidase alfa in patients with Fabry’s disease: an analysis of registry data. Lancet. 2009;374:1986-96.

3. Rigoldi M, Concolino D, Morrone A, et al. Intrafamilial phenotypic variability in four families with Anderson-Fabry disease. Clin Genet. 2014;86:258-63.

4. Tuttolomondo A, Simonetta I, Duro G, et al. Inter-familial and intra-familial phenotypic variability in three Sicilian families with Anderson-Fabry disease. Oncotarget. 2017;8:61415-24.

5. Orsborne C, Anton-Rodrigez JM, Sherratt N, et al. Inflammatory fabry cardiomyopathy demonstrated using simultaneous [18F]-FDG PET-CMR. JACC Case Rep. 2023;15:101863.

6. Rozenfeld PA, de Los Angeles Bolla M, Quieto P, et al. Pathogenesis of fabry nephropathy: the pathways leading to fibrosis. Mol Genet Metab. 2020;129:132-41.

7. Land WG. The role of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) in human diseases: part II: DAMPs as diagnostics, prognostics and therapeutics in clinical medicine. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2015;15:e157-70.

8. Rozenfeld P, Agriello E, De Francesco N, Martinez P, Fossati C. Leukocyte perturbation associated with Fabry disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32:67-77.

9. De Francesco PN, Mucci JM, Ceci R, Fossati CA, Rozenfeld PA. Fabry disease peripheral blood immune cells release inflammatory cytokines: Role of globotriaosylceramide. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;109:93-9.

10. Biancini GB, Vanzin CS, Rodrigues DB, et al. Globotriaosylceramide is correlated with oxidative stress and inflammation in Fabry patients treated with enzyme replacement therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:226-32.

11. De Francesco PN, Mucci JM, Ceci R, Fossati CA, Rozenfeld PA. Higher apoptotic state in Fabry disease peripheral blood mononuclear cells: effect of globotriaosylceramide. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;104:319-24.

12. Moore DF, Goldin E, Gelderman MP, et al. Apoptotic abnormalities in differential gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from children with Fabry disease. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:48-52.

13. Heo SH, Kang E, Kim YM, et al. Fabry disease: characterisation of the plasma proteome pre- and post-enzyme replacement therapy. Med Genet. 2017;54:771-80.

14. Moore DF, Krokhin OV, Beavis RC, et al. Proteomics of specific treatment-related alterations in Fabry disease: a strategy to identify biological abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2873-8.

15. Pandey MK. Exploring pro-inflammatory immunological mediators: unraveling the mechanisms of neuroinflammation in lysosomal storage diseases. Biomedicines. 2023;11:1067.

16. Frustaci A, Verardo R, Grande C, et al. Immune-mediated myocarditis in Fabry disease cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009052.

17. Schumann A, Schaller K, Belche V, et al. Defective lysosomal storage in Fabry disease modifies mitochondrial structure, metabolism and turnover in renal epithelial cells. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2021;44:1039-50.

18. An JH, Hong SE, Yu SL, et al. Ceria-zirconia nanoparticles reduce intracellular globotriaosylceramide accumulation and attenuate kidney injury by enhancing the autophagy flux in cellular and animal models of Fabry disease. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20:125.

19. Rozenfeld P, Feriozzi S. Contribution of inflammatory pathways to Fabry disease pathogenesis. Mol Genet Metab. 2017;122:19-27.

20. Fan JQ, Ishii S, Asano N, Suzuki Y. Accelerated transport and maturation of lysosomal alpha-galactosidase A in Fabry lymphoblasts by an enzyme inhibitor. Nat Med. 1999;5:112-5.

21. Grootjans J, Kaser A, Kaufman RJ, Blumberg RS. The unfolded protein response in immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:469-84.

22. Zhang K, Shen X, Wu J, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates cleavage of CREBH to induce a systemic inflammatory response. Cell. 2006;124:587-99.

23. Meares GP, Liu Y, Rajbhandari R, et al. PERK-dependent activation of JAK1 and STAT3 contributes to endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced inflammation. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:3911-25.

24. Consolato F, De Fusco M, Schaeffer C, et al. α-Gal A missense variants associated with Fabry disease can lead to ER stress and induction of the unfolded protein response. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2022;33:100926.

25. Janssens S, Pulendran B, Lambrecht BN. Emerging functions of the unfolded protein response in immunity. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:910-9.

26. Braunstein H, Papazian M, Maor G, Lukas J, Rolfs A, Horowitz M. Misfolding of lysosomal α-galactosidase a in a fly model and its alleviation by the pharmacological chaperone migalastat. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7397.

27. Nikolaenko V, Warnock DG, Mills K, Heywood WE. Elucidating the toxic effect and disease mechanisms associated with Lyso-Gb3 in Fabry disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2023;32:2464-72.

28. Fogo AB, Bostad L, Svarstad E, et al. Scoring system for renal pathology in Fabry disease: report of the International Study Group of Fabry Nephropathy (ISGFN). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:2168-77.

29. Sanchez-Niño MD, Sanz AB, Carrasco S, et al. Globotriaosylsphingosine actions on human glomerular podocytes: implications for Fabry nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1797-802.

30. Sanchez-Niño MD, Carpio D, Sanz AB, Ruiz-Ortega M, Mezzano S, Ortiz A. Lyso-Gb3 activates Notch1 in human podocytes. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:5720-32.

31. Vujkovac B, Srebotnik Kirbiš I, Keber T, Cokan Vujkovac A, Tretjak M, Radoš Krnel S. Podocyturia in Fabry disease: a 10-year follow-up. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15:269-77.

32. Feriozzi S, Rozenfeld P. Pathology and pathogenic pathways in Fabry nephropathy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2021;25:925-34.

33. Anders HJ, Banas B, Schlöndorff D. Signaling danger: toll-like receptors and their potential roles in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:854-67.

34. Matafora V, Cuccurullo M, Beneduci A, et al. Early markers of Fabry disease revealed by proteomics. Mol Biosyst. 2015;11:1543-51.

35. Doykov ID, Heywood WE, Nikolaenko V, et al. Rapid, proteomic urine assay for monitoring progressive organ disease in Fabry disease. J Med Genet. 2020;57:38-47.

36. Biancini GB, Jacques CE, Hammerschmidt T, et al. Biomolecules damage and redox status abnormalities in Fabry patients before and during enzyme replacement therapy. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;461:41-6.

37. Shu L, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Pennathur S, et al. Establishing 3-nitrotyrosine as a biomarker for the vasculopathy of Fabry disease. Kidney Int. 2014;86:58-66.

38. Aerts JM, Groener JE, Kuiper S, et al. Elevated globotriaosylsphingosine is a hallmark of Fabry disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2812-7.

39. Do HS, Park SW, Im I, et al. Enhanced thrombospondin-1 causes dysfunction of vascular endothelial cells derived from Fabry disease-induced pluripotent stem cells. EBioMedicine. 2020;52:102633.

40. Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. Mechanisms of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1819-34.

42. Gai Z, Gui T, Kullak-Ublick GA, Li Y, Visentin M. The role of mitochondria in drug-induced kidney injury. Front Physiol. 2020;11:1079.

43. Jeon YJ, Jung N, Park JW, Park HY, Jung SC. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in kidney tubular epithelial cells induced by globotriaosylsphingosine and globotriaosylceramide. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136442.

44. Taguchi A, Maruyama H, Nameta M, et al. A symptomatic Fabry disease mouse model generated by inducing globotriaosylceramide synthesis. Biochem J. 2013;456:373-83.

45. Taguchi A, Ishii S, Mikame M, Maruyama H. Distinctive accumulation of globotriaosylceramide and globotriaosylsphingosine in a mouse model of classic Fabry disease. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2023;34:100952.

46. Turkmen K, Karaselek MA, Celik SC, et al. Could immune cells be associated with nephropathy in Fabry disease patients? Int Urol Nephrol. 2023;55:1575-88.

47. Hughes D, Linhart A, Gurevich A, Kalampoki V, Jazukeviciene D, Feriozzi S. FOS Study Group. Prompt agalsidase alfa therapy initiation is associated with improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes in a fabry outcome survey analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021;15:3561-72.

48. Khan A, Sirrs SM, Bichet DG, et al. Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative. The Safety of agalsidase alfa enzyme replacement therapy in canadian patients with Fabry disease following implementation of a bioreactor process. Drugs R D. 2021;21:385-97.

49. Battaglia Y, Bulighin F, Zerbinati L, Vitturi N, Marchi G, Carraro G. Dapaglifozin on albuminuria in chronic kidney disease patients with Fabry disease: the DEFY study design and protocol. J Clin Med. 2023;12:3689.

50. Braun F, Blomberg L, Brodesser S, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy clears Gb3 deposits from a podocyte cell culture model of fabry disease but fails to restore altered cellular signaling. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2019;52:1139-50.

51. Jehn U, Bayraktar S, Pollmann S, et al. α-galactosidase a deficiency in Fabry disease leads to extensive dysregulated cellular signaling pathways in human podocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:11339.

52. Braun F, Abed A, Sellung D, et al. Accumulation of α-synuclein mediates podocyte injury in Fabry nephropathy. J Clin Invest. 2023;133:e157782.

53. Germain DP. Reconceptualizing podocyte damage in Fabry disease: new findings identify α-synuclein as a putative therapeutic target. Kidney Int. 2024;105:237-9.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].