Managing rare diseases: examples of national approaches in Europe, North America and East Asia

Abstract

Around 4% of the global population suffers from a rare disease. Apart from the medical aspect, economic, organisational, and political approaches remain key aspects when it concerns the evolution of the world of rare diseases. We review here the principal specific national initiatives and organisations in Europe, North America and East Asia. Thereafter, we propose the outlines of a possible optimal approach, inspired by the successes of the individual national organisations. This work should be taken into account in the definition of large scale multi-national rare diseases programs, such as the European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Rare diseases affect 300 million people worldwide, equivalent to 4% of the global population, of which 30 million are in Europe. The first countries to implement a healthcare policy on orphan diseases were Japan, with the Nan-Byo (“difficult + illness” in Japanese) Consortium in 1972, and the United States, with the Orphan Drug Act in 1983. France followed in 2004 with its National Plan for Rare Diseases, setting an example for other European countries and Canada [Figure 1]. As of today, Malta and Sweden are the only European Union (EU) member states lacking a plan in place for rare diseases.

Figure 1. Implementation of national plans and strategies dedicated to rare diseases and their management in Europe, North America and East Asia.

This study describes the national state-coordinated transdisciplinary approaches put in place to support patients with rare diseases and oversee their access to healthcare in Europe, North America, and East Asia. It then seeks to identify efficient initiatives that could be replicated in order to bring together all stakeholders in the rare disease health system. This type of approach could benefit patients and accelerate the development of breakthrough innovations. Given that the purpose of this paper is to study the initiatives and organizations specific to each country, it will not look closely into the organization of this sector at the European Commission (EC) level, nor at the patient organization level. However, considering their essential role, these two levels will be mentioned briefly.

The EC is the politically independent executive arm of the EU since 2008. It is responsible for drawing up proposals for new European legislation, and it implements the decisions of the European Parliament and the Council of the EU. The EC has been active in the field of rare diseases, making it a priority even though Europe was already involved in rare diseases, especially with the implementation of the European regulation No 141/2000 on orphan medicinal products in 2000. The commitment of the EC notably led to the creation in 2009 of the European Committee of Experts on Rare Diseases, which aimed to assist the EC with the preparation and implementation of activities in the field of rare diseases. This commitment also allowed the funding of shared tools for European member states, such as the European Reference Networks (ERNs), networks of centers of expertise, healthcare providers, and laboratories organized across borders; the European Joint Program on Rare Diseases (EJPRD), a program aiming to create an effective rare diseases research ecosystem for progress and innovation for the benefit of everyone with a rare disease; the European Platform on Rare Disease Registration (EU RD Platform), tasked with making data from rare disease registries searchable at the EU level and standardizing data collection and exchange in order to solve the problem of fragmentation of rare disease data; and the European Rare Disease Research Coordination and Support Action (ERICA) Consortium in 2021, a platform that integrates the research and innovation capacity of the 24 ERNs. An entire paper could be written on the commitment of the EC, its work in bringing players together, and the diversity of programs funded in the field of rare diseases.

Patient organizations are defined as non-profit patient-focused organizations whereby patients and/or carers (when patients are unable to represent themselves) represent a majority of members in governing bodies. These organizations provide moral, practical, financial, social, and legal support to patients and their families, but they are also able to contribute to research funding and are important partners for health professionals, decision-makers, and pharmaceutical laboratories.

METHOD

The selection of the countries included was first made on a geographical criterion. Indeed, we limited the work to Europe, East Asia, and North America.

In Europe, we decided to present an exhaustive overview of the national approaches present in the different countries. They were then selected according to the availability and accessibility of the information concerning the national approaches to rare diseases.

In North America and East Asia, the countries were selected using arbitrary criteria. Indeed, Japan and the United States were selected because they represent the first countries to implement a national approach for rare diseases, while Canada was selected because it is considered a pioneer in gene identification.

All the data used hereafter was obtained from legal texts and from the organizations involved in the different national approaches.

RESULTS

Approaches to rare diseases

European countries

All the European countries mentioned below use the same definition for rare diseases. This definition is provided by the European Medicines Agency (EMA): “a disease is considered rare if fewer than five in 10,000 people have it”.

1. Germany: Since 2020, Germany has stepped up its commitment to research in the field of rare diseases.

(a) The German National Action League for People with Rare Diseases (NAMSE) was set up by the Federal Ministry of Health (BMG) in 2010. It is jointly coordinated by the BMG, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), and the National Alliance for Chronic Rare Diseases (ACHSE). NAMSE is responsible for the implementation, coordination, and follow-up of the rare disease plan. ACHSE brings together 28 partners, including the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, the German Medical Association, and the National Health Insurance Association[1]. As part of this organization, the German plan for rare diseases came into force in August 2013.

(b) Thirty-six centers of expertise collaborate with a network of 11 research centers, led by a Board of Directors.

(c) The SE-ATLAS platform for healthcare providers and patients. The SE-ATLAS platform (https://www.se-atlas.de/) stores data that will help improve diagnosis and facilitate innovation[2]. In February 2020, the BMBF launched CORD-MI (Collaboration on Rare Diseases - Medical Informatics), a two-year project with funding of €6 million. Led by the Institute of Health in Berlin, the purpose of the project is to collect and structure data relating to rare diseases as part of a digital network. This will then be incorporated into the BMBF Medical Informatics Initiative (MII). The MII was set up to develop an infrastructure for the integration of all patient clinical data, regardless of the field. By late 2022, the BMBF will have invested around €180 million in the MII[3].

(d) Alongside these commitments, the BMBF has announced plans to invest €3 million every year from 2021 in a new center for neurodegenerative diseases (DZNE) in Ulm. This takes the number of DZNEs to ten[4].

(e) Further, in January 2021, the BMBF announced the launch of an independent Fraunhofer research center dedicated to translational medicine and pharmacology (Fraunhofer ITMP)[5,6]. With research sites in Frankfurt, Hamburg, and Göttingen, the Fraunhofer ITMP will develop innovative solutions in collaboration with the industry and with the support of government funding. Its objectives are to transfer innovations into medical applications and to train future leaders in the field of biomedical research.

Between 2003 and 2018, the BMBF invested €107 million in the field of rare diseases.

2. Spain: The Spanish Undiagnosed Rare Diseases Program (SpainUDP) is Spain’s main program for undiagnosed rare diseases. In Spain, the rare diseases program is led by the Carlos III Health Institute (ISCIII). The ISCIII is a public health research institute founded in 1986 to promote research into biomedicine and health sciences and to develop and steer the scientific and technical strategies of the Spanish national health system. Located on two campuses in Madrid, it helps to promote research and innovation in the health sciences sector. It also provides scientific and technical services and educational programs[7]. Within the ISCIII, the Institute of Rare Diseases Research (IIER) is studying the mechanisms underpinning the origin and progression of rare diseases and congenital malformations. The goal of the research projects is to develop innovative treatments. The IIER is developing several translational programs:

(a) SpainUDP was set up to address the high number of consultations for undiagnosed rare diseases. It offers patients a multidisciplinary approach. In 2014, the SpainUDP program became part of the Undiagnosed Diseases Network International (UDNI), a global consortium of research centers and institutes. The partners and tools of SpainUDP are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Partners and tools of SpainUDP (© 2022 SpainUDP). SpainUDP: Spanish undiagnosed rare diseases program.

(b) The Rare Disease Patient Registry (SpainRDR) provides healthcare professionals, researchers, patient groups and their families with extensive information on the number and geographical distribution of people affected by rare diseases in Spain. SpainRDR is co-funded by the ISCIII, the Regional Health Departments, and the Ministry of Health and Social Services. Its objective is to increase the visibility of rare diseases and support decision making in order to ensure adequate health planning and resource allocation. SpainRDR works with hospitals, a network of scientists, patient organizations, and the pharmaceutical industry.

(c) The National Biobank for Rare Diseases (BioNER) provides the scientific community with a catalogue of biological samples associated with clinical and epidemiological information on these diseases.

(d) The Human Genetic Area (AGH) includes a Genetic Diagnosis Service offering services for the diagnosis of the various genetic diseases identified. This center is equipped with state-of-the-art technologies such as high-throughput sequencing and large-scale data analysis.

3. France: a pioneer in Europe with the first Rare Disease Plan in 2004, France has maintained its leadership since then.

Rare diseases are a priority for France. The Public Health Act of 2004 led to the creation of a National Plan for Rare Diseases (PNMR), which has been renewed twice (PNMR2 and PNMR3). As part of the PNMR3, the state oversees healthcare and research activities. For these purposes, it is represented by the Ministry of Solidarity and Health and the Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation. These initiatives have made it possible to accelerate patient care, boost teaching and training, and drive progress in research and innovation. They are organized as follows:

(a) Nearly 400 Reference Centers for Rare Diseases (CRMRs) with a coordinating site and one or more constituent sites. A CRMR brings together a highly specialized hospital-based team with proven expertise in a particular rare disease or group of rare diseases. Each CRMR develops activities in the fields of prevention, healthcare, teaching, and research. The medical team includes paramedical, psychological, medicosocial, educational, and social skills experts. It also forms partnerships with patient organizations. A CRMR is a multi-site entity. It is an expert referral center of a regional, interregional, national, and even international scope.

(b) Twenty-three National Rare Disease Clinical Networks (FSMRs). The FSMRs were set up in 2014-2015 as part of the PNMR2. They each cover a broad but coherent field of rare diseases. Each FSMR groups the stakeholders involved in a given area, including caregivers, researchers, patient representatives, and manufacturers. Each FSMR pursues three goals: better healthcare, research and education, and training and information.

(c) At the same time, the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) is coordinating the EJPRD, a flagship program co-funded by the EU, with the purpose of structuring the rare disease ecosystem at European and international levels.

(d) The BaMaRa national register, developed by the National Data Bank for Rare Diseases (BNDMR), has now reached the deployment stage. This process involves staff training, data entry checks, data exhaustiveness checks, administrative follow-up, and harmonization of coding. Connected to the National Health Data System (SNDS), the BaMaRa register aims to develop medical-economic knowledge on rare diseases and to conduct epidemiological studies to better assess the prevalence and incidence of rare diseases.

(e) Orphanet. Created in France in 1997, Orphanet was initially developed to gather scarce information concerning rare diseases to improve the diagnosis and treatment of patients. Orphanet has now become a network of 41 countries throughout Europe and the world and represents the reference source of information on rare diseases. The objectives of Orphanet are: to provide a common language in rare diseases with ORPHAcodes (Orphanet Nomenclature of Rare Diseases) to have a better comprehension between the actors; to provide high-quality data and expertise on rare diseases to allow equal access to knowledge, and guide users in the field of rare diseases; and to contribute to a better understanding of rare diseases.

(f) The French national program on Rare Disease Cohorts, RaDiCo, aims to establish national and international cohorts of patients with rare diseases. The objective is to better describe the diseases, establish phenotype/genotype correlations, understand the physiopathology, identify new therapeutic targets, and evaluate the medico-economic and societal impact of the diseases.

The PNMR3 (2018-2022) has a budget of €778 million, most of which (€597 million) is dedicated to the CRMRs. The initiatives in place include collaborative work with the France Genomic Medicine 2025 plan to facilitate access to very-high-throughput sequencing platforms, in accordance with a scale based on the clinical situation.

Finally, France has internationally renowned research institutes involving public and private partners:

- The Imagine Foundation was set up to conduct a project of medical and scientific excellence by organizing, structuring, and developing research, healthcare, and teaching activities in the field of genetic diseases affecting both children and adults.

- I-Motion is a clinical trial center dedicated to children with neuromuscular diseases.

- The Institute of Myology promotes the existence, recognition, and growth of myology as a discipline in its own right. The muscular system is a true model of innovation for scientific and medical research.

- The NeuroMyoGene Institute is dedicated to studying the physiopathology of the muscular and nervous system, with an opening in clinical and translational research.

- The French Foundation for Rare Diseases is dedicated to the coordination and acceleration of research on all rare diseases.

4. The United Kingdom (UK): an ambitious program of government investment launched in 2012 has created a highly structured and efficient system that also includes private-sector partners.

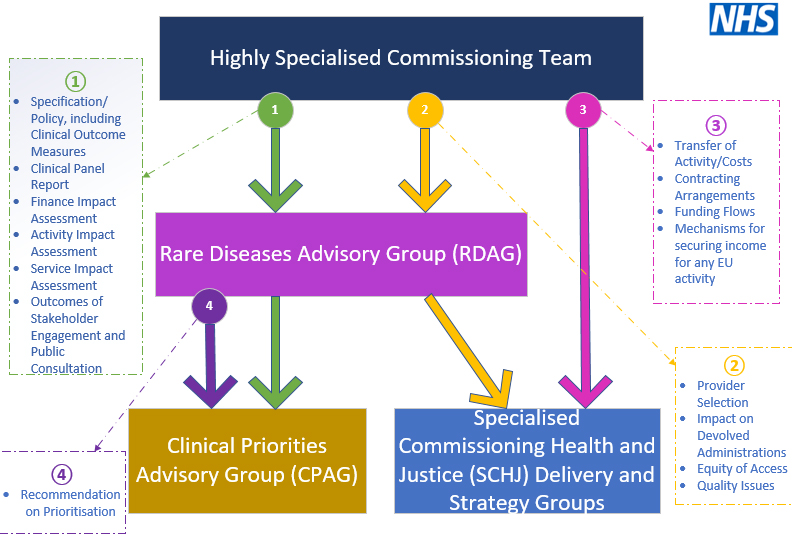

(a) Within the National Health Service (NHS), the Highly Specialized Services (HSSs) are a network of 76 centers specializing in rare diseases[8]. The HSSs place emphasis on patient care and empowerment, with each center treating no more than 500 patients per year. For the 2018/2019 financial year, the NHS provided €19.8 billion for the running of the 76 centers[8]. The governance of the Rare Diseases Advisory Group is described in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Governance of the Rare Diseases Advisory Group (Terms of reference, Rare Diseases Advisory Group, March 2020). NHS: National health service.

(b) At the same time, 13 genomic medicine centers were set up in 2019 with the participation of 85 hospitals. Their aim is to sequence 50,000 genomes by 2023. These initiatives are coordinated with the Cell and Gene Therapy (CGT) Catapult launched in April 2012.

(c) The Catapult centers[9]. The nine Catapult centers are private, independent organizations. Similar to Germany’s Fraunhofer research centers, they have a mixed-funding model based on an equal split between:

- Grants awarded to each center by Innovate UK (state funding and innovation body), primarily for the purposes of infrastructure and the development of expertise. This grant can total up to €12 million per center.

- Research and Development contracts and services, financed by the private sector.

- Grants obtained through calls for proposals from funding agencies.

The CGT Catapult[10] as set up to drive progress in gene and cell therapy at the UK and international levels. Its mission is to:

- Conduct clinical trials.

- Deliver an infrastructure equipped to the standards required by Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs).

- Provide expertise on regulatory issues (shorter start-up times for clinical trials).

- Set up national and international collaborative projects.

- Gain access to grants and funding.

Located in London, the CGT Catapult has a process development laboratory with dedicated facilities for clinical trials and reproducibility studies. Further, the CGT Catapult site in Stevenage, which opened in 2018 at a cost of €92 million (of which €4 million was funded by the EU), is an industrial-scale manufacturing center. This center is dedicated to manufacturing gene and cell therapy products in collaboration with the industry[11].

The CGT Catapult has 64 public and private partners, including UK universities and manufacturers (40 in all), as well as a number of British and international organizations. The main achievements of the CGT Catapult since 2013 are as follows:

- Nearly €3 billion in industrial investment.

- 26 production units meeting GMP standards.

- 47 companies on campus.

- Over 90 therapies at the development stage.

- 60% of therapies developed in the UK in this field are based on collaborations with the CGT Catapult.

- A 45% increase in clinical trials.

In 2019/2020 alone, the GCT Catapult achievements were:

- 108 projects.

- €7.8 million investment in gene and cell therapy.

- 28 phase III clinical trials.

- 10 spin-outs.

- 7 drugs reimbursed for patients.

- €349 million invested by the industry in rare diseases.

- Over 3,000 jobs.

North America

5. Canada: globally renowned expertise in gene identification. In Canada, by definition, a rare disease is a disease that affects fewer than 5 in 10,000 Canadians. Although Canada only developed a National Plan for Rare Diseases in 2015, it has developed internationally recognized expertise in identifying the genes involved in rare diseases.

(a) Set up in 2000, Genome Canada is a not-for-profit organization supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research, Institute of Genetics (CIHR IG)[12]. It coordinates federal and provincial studies through six genome centers with the following missions:

- Develop ties between public and private players.

- Invest in major scientific and technological projects.

In 2017, for example, Genome Canada invested €7 million in the Silent Genome Project led by researchers from the University of British Columbia, whose purpose is to create a database of genetic variations in indigenous populations around the world[13].

(b) The Rare Diseases Models and Mechanisms (RDMM) is a national network coordinating research projects to gain a clearer understanding of the biology underlying rare diseases in children. It is funded by Genome Canada[14]. Present across Canada, the RDMM is managed by the Maternal Infant Child & Youth Research Network (MICYRN), which brings together 23 networks of experts and 20 hospitals and academic research centers specializing in maternal and childhood diseases.

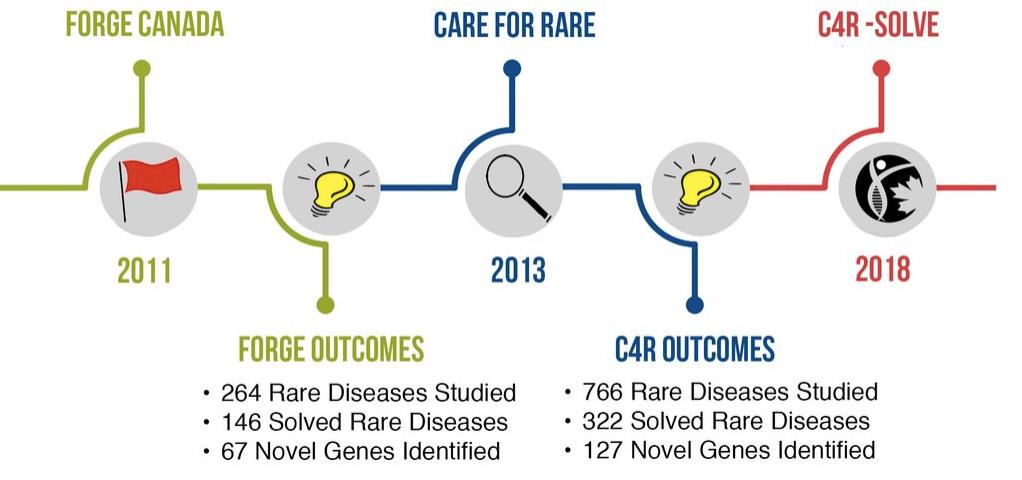

The diagram presented in Figure 4 shows the timeline of research studies conducted by the RDMM as part of the FORGE (Finding of Rare Disease Genes in Canada) program, which became the international research consortium Care4Rare (C4R) in 2013.

Figure 4. Timeline of the research studies led by the RDMM (© Copyright 2014. “Rare Diseases: Models & Mechanisms Network” All rights reserved). RDMM: Rare diseases models and mechanisms.

(c) C4R[15] brings together Canadian clinicians, bioinformaticians, scientists, and researchers working on the care of patients with rare diseases in Canada and around the world. Led by the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario and the Ottawa Research Institute in Ottawa, it has 21 academic centers across Canada with 200 physicians and 100 scientists.

(d) C4R-SOLVE[15] uses innovative new sequencing technologies based on omics approaches to build an infrastructure with the tools necessary to improve the diagnosis of rare diseases worldwide. Omics technologies use a transdisciplinary approach (chemistry, physics, and information technology) for a systematic analysis of the content of living cells at the molecular level.

(e) In 2014, the PhenomeCentral system brought together research and diagnosis in a single portal. Developed by the Centre for Computational Medicine at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, this connected system is able to secure data[16]. It provides a global link between patients with identical genotypes and phenotypes, as well as clinicians and scientists working on similar cases. PhenomeCentral is funded by the CIHR IG, the Ontario Genomics Institute, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC). It is a partner of the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH), RD-Connect (an

(f) Ontario Genomics is a not-for-profit organization supported by the CIHR IG and the government of Ontario. It brings together companies, researchers, policy makers, and funders to generate funding and accelerate the development of genomics[17].

(g) The Canadian Organization for Rare Diseases (CORD) was set up by the Canadian Parliament in 2015[18]. Its main priorities are to:

- Implement a regulatory framework.

- Put in place appropriate funding for equitable patient access to treatment.

- Identify centers of excellence bringing together research, patients, and care.

- Set up a program for the screening of newborn babies.

In 2019, the CIHR announced an investment of €680 million in rare diseases[19]. Primarily dedicated to ensuring patient access to healthcare, this sum will be divided into two equal payments in 2022 and 2023.

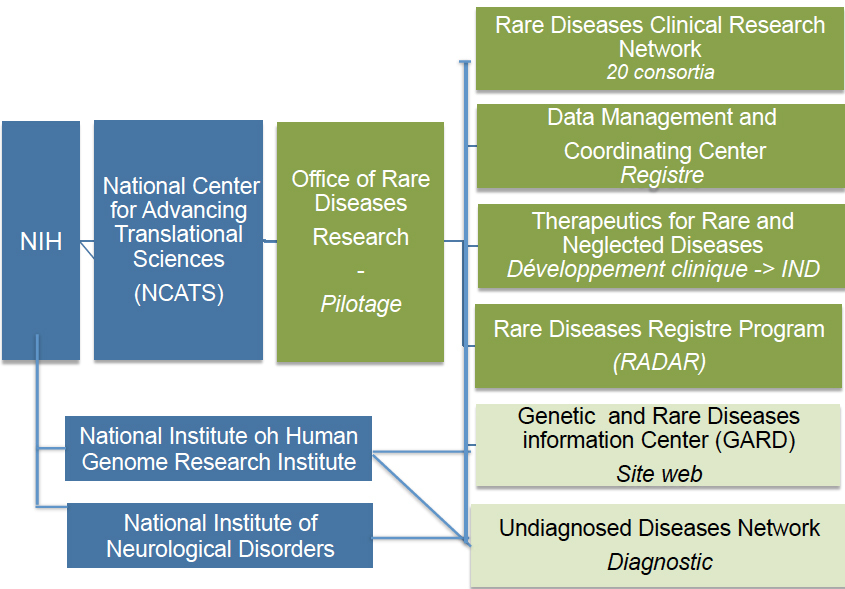

6. United States: in 2012, the USA put in place an accelerated registration process for ultra-rare diseases[20]. The Orphan Drug Act of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines a rare disease as a disease or condition that affects fewer than 200,000 people in the United States. As is often the case in the United States, resources are provided by the national, i.e., federal, government. The NIH plays a key role in the field of rare diseases. As presented in Figure 5, the NIH is structured as follows:

Figure 5. Organization of the NIH for the study of rare diseases. NIH: National Institutes of Health; IND: investigational new drug.

(a) The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) is one of the 27 institutes making up the NIH. It comprises seven divisions, one of which is dedicated to rare diseases. The grant received by the NIH in 2020 totaled €722 million, or 0.2% of its budget (€35 billion)[21].

(b) The Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR) is the steering organization of the NCATS Rare Disease Division[22].

(c) Founded in 2003 by the NIH, the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN) is made up of 20 consortia specializing in clinical research, bringing together scientists, clinicians, patients, and associations, i.e., 2,600 experts at present[23,24]. Since its founding, the RDCRN has studied over 280 diseases and recruited around 40,000 patients for clinical trials.

(d) The Data Management and Coordinating Center (DMCC) is based at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. It collects, homogenizes, manages, and shares RDCRN data to increase dissemination for research purposes.

(e) The Therapeutics for Rare and Neglected Diseases (TRND) program is involved in all stages of drug development, from pre-clinical development through to submission of an investigational new drug (IND) to the FDA. It brings together NIH academic research teams and private partners to accelerate the development of new molecules. One of the activities of TRND is to seek new applications for compounds that have already passed clinical trial phases[25].

(f) The Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) is a website set up to provide information that can be easily understood by all audiences[26]. GARD is funded by the NCATS and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), another department of the NIH. It is connected to Orphanet.

(g) The Rare Diseases Registry Program (RaDaR) is a website dedicated to patients, their families, researchers, and the public[27]. It is currently in phase 1.

(h) The Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN) is funded by the NHGRI, the NCATS, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)[28]. Its 12 sites bring together clinicians and scientific experts pooling their efforts to accelerate gene identification. Since its launch in 2015, 200 cases have been diagnosed.

The university is the basic entity in research and development, whether clinical (hospitals and medical schools) or fundamental (research laboratories). Most funding is private, with the contribution from the federal government making up to around 20% of the total.

Since 2012, the FDA has simplified the regulations governing clinical research in the field of rare diseases. Special terms are made available to manufacturers: financial and tax support, and accelerated procedures for bringing new products to the market.

East Asia

1. Japan: a forerunner in the field of detection, Japan uses innovative technologies for whole genome and exome sequencing. The exome is the part of the genome most directly linked to the phenotype of the organism, to its structural and functional qualities. In Japan, rare diseases are defined as conditions with a prevalence of fewer than 50,000 and no known cause or cure.

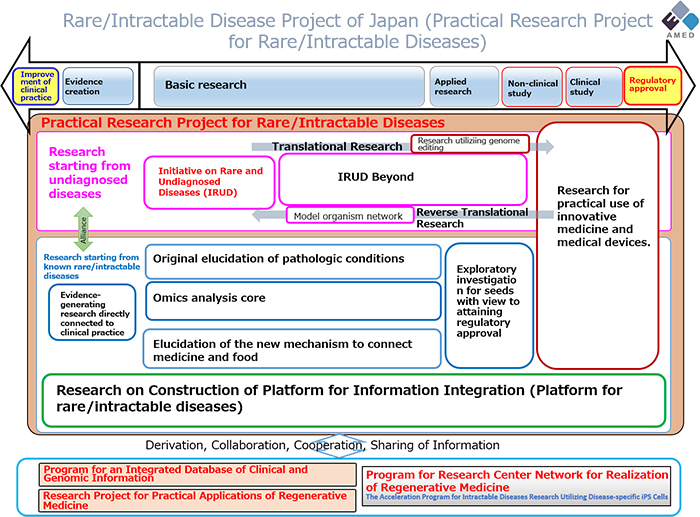

Implemented in 2014, the Japanese Plan for Rare and Undiagnosed Diseases succeeded in the rare disease research program set up in 1972 by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under the name “Nan-Byo Research”[29,30]. The Ministry of Health is a key player in the new plan, led by AMED. It involves 34 clinical investigation centers and four analysis centers, and funds around 500 doctors and 50 coordinators belonging to the National Coordination Committee[31]. The plan for rare diseases

Figure 6. Japan project for rare diseases (Copyright © Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. All rights reserved).

- Pathology and mechanism of rare diseases.

- Repositioning of existing drugs and medical devices for clinical use in patients suffering from rare diseases.

- Improved clinical practices (training) to optimize the effectiveness of healthcare.

- Use of innovative omics technologies.

- Implementation of the Initiative on Rare and Undiagnosed Diseases (IRUD).

- Creation of a data registry compatible with international standards.

- Development of innovative drugs using gene therapy or nucleic acids.

- Production of vectors for the development of new therapies.

- Research into the links between medicine, nutrition, and the physiological aspects of rare diseases.

In line with these priorities, AMED has put in place the following approach:

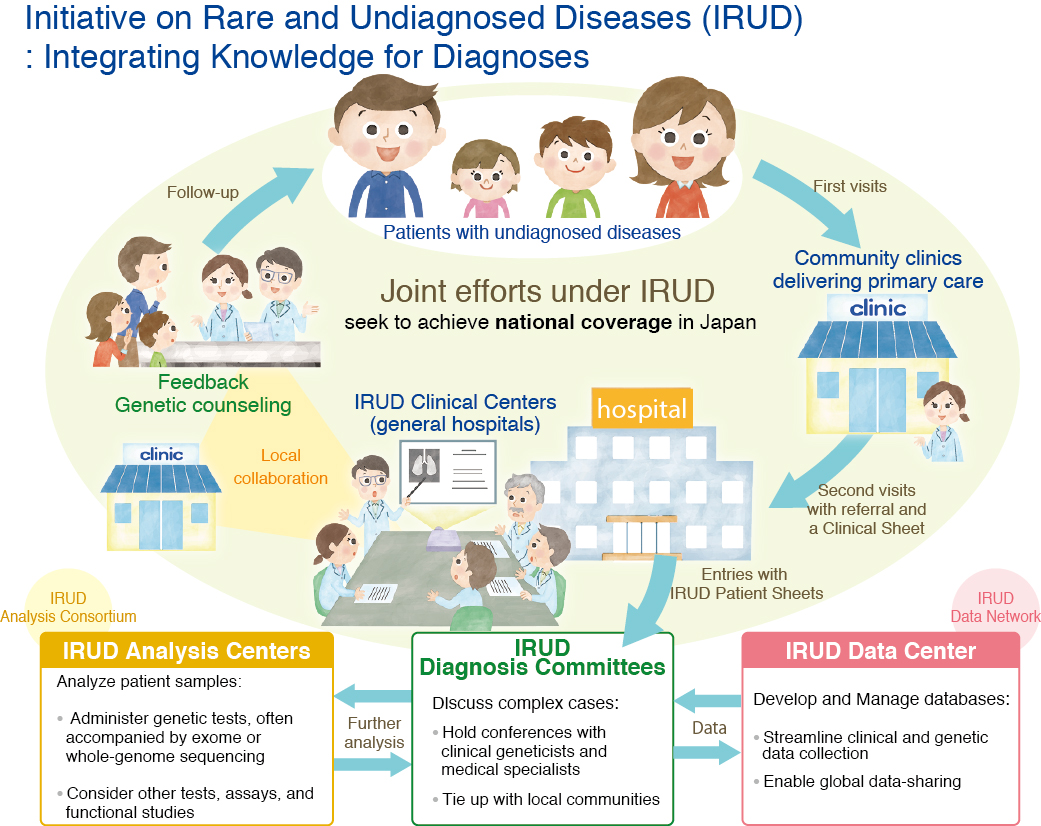

(a) The IRUD, implemented by AMED in 2015, is part of Japan’s Rare Disease Plan[31]. IRUD is a national consortium that brings together patients, physicians, and researchers as part of the process shown in [Figure 7].

Figure 7. Initiative on Rare and Undiagnosed Diseases (IRUD) (Copyright © Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. All rights reserved).

(b) Launched by AMED in February 2017 and funded by AMED and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, the National Platform for the Rare Diseases Data Registry of Japan (RADDAR-J) collects and structures data from research projects into rare diseases[33]. The experts involved in the IRUD consortium are connected to this registry, which includes data relating to over 2,000 undiagnosed patients[31]. The database is designed to be linked to international platforms in compliance with the standards set out by the IRDiRC as part of the Automatable Discovery and Access Matrix[34]. In the longer term, AMED is seeking a connection with the international platform of the IRDiRC, scheduled for launch in 2027.

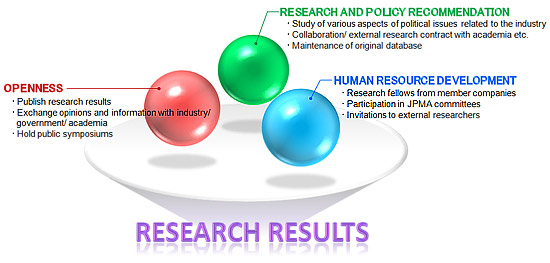

(c) The Office of Pharmaceutical Industry Research (OPIR) was set up in January 1999 by the Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (JPMA). The JPMA represents the research-based pharmaceutical industry in Japan and has 74 members, including 20 overseas affiliates. The OPIR analyzes the internal and external environment of the Japanese pharmaceutical industry (in all fields), identifying the mid- and long-term issues, with a view to submitting recommendations to policy makers[35]. The OPIR has developed an economic and social structure that contributes to the rapid development of medical innovation. The OPIR is an open laboratory for research, policy recommendations, and the development of human resources [Figure 8]. The structure supports its own research projects as well as collaborating with third parties.

DISCUSSION

Outlining an optimal approach

The description of the seven approaches coordinated by governments to support and treat patients with rare diseases [Table 1] shows a number of strengths [Table 2] but also a number of divergences. The approach adopted by each country reflects its history, the commitment of the state, the organization of the healthcare and biomedical research systems, national legislation, and the culture regarding innovation and public-private partnerships.

Comparison of different approaches based on specific key criteria

| Steering | Source of funding | Centers of expertise | Gene identification | National register | |

| Germany 2013 | State + patient organization (ACHSE) | State + patient organization (ACHSE) | 36 centers working with 8 research centers + 10 DZNEs | RD-Connect program (EU funding 2018-2022): -> register relating to research Biobanks and the creation of an EU platform | SE-ATLAS: 8,000 genes CORD-MI project €160 million invested between 2016 and 2021 |

| Spain 2009 | State | State | 19 centers of expertise SpainUDP consortium | The Human Genetic Area (AGH) for diagnosed diseases. SpainUDP for undiagnosed diseases | SpainRDR Funding from the state/regions and collaboration with private partners |

| France 2004 | State | State | 400 CRMRs; 27 FSMRs | France Genome 2025 program High-throughput platform | Deployment of the BaMaRa register |

| United Kingdom 2012 | State | State | 76 centers Emphasis on patient care and empowerment | 13 centers, involving 85 hospitals Target 2023: sequencing of 50,000 genes | - |

| Canada 2015 | State: CORD | Genome Canada, funded by the federal government, the provinces and manufacturers | 20 mother and child research centers | 6 genomic centers Care4Rare, international, transdisciplinary consortium, with 21 sites | PhenomeCentral: national register with an international scope |

| USA 1983 | State: NIH | State | Network of 20 consortia, with 350 sites in the United States and 22 worldwide | Undiagnosed Diseases Network (2015), with 12 sites | DMCC |

| Japan 1972 | State | State | 34 clinical investigation centers 4 analysis centers | Consortium for the IRUD | RADDAR platform connected to international platforms |

Strengths of national approaches

| Public/private partnership (PPP) | Key points of national programs | |

| Germany | 2021, creation of a state-funded program dedicated to translational medicine and pharmacology (Fraunhofer ITMP): Development of innovative solutions in partnership with industry and training | - PPP: translational research targeting rare diseases: ≥ rationalization - The Fraunhofer business model has demonstrated its efficiency in other fields |

| Spain | SpainRDR register: collaboration with private partners | - SpainUDP program, many national and international connections - SpainRDR register: Collaboration with private partners |

| France | 5 Institutes of Excellence (healthcare, teaching, training, translational research). PPP, involves manufacturers from the outset | - Organization of centers of expertise and healthcare networks for rare diseases - Strong EU involvement as part of the JPRD - PPP: IHU university-hospital institutes, centers of healthcare excellence and translational research |

| United Kingdom | - CGT Catapult, private: clinical trials, provision of infrastructure, search for funding from manufacturers - Stevenage Centre, dedicated to gene and cell therapy manufacturing | - Structure: strong state involvement - Patient healthcare and empowerment - PPP: CGT Catapult involves 64 public and private partners |

| Canada | - Genomic Canada: manages funds from the state, provinces, and industry to invest in PPP projects - Ontario Genomic, supported by the government and the State of Ontario, brings together PP players to accelerate genomic development | - Private partners involved from the outset - gene identification: international collaboration as part of the Care4Rare consortium - PhenomeCentral register |

| USA | - TRND, the state funds the development of molecules through to the submission of an IND as part of a PPP - Co-funding with industry in universities | - Structure: Strong state involvement - FDA: Simplified regulations - State funding -> filing of an IND as part of a PPP - PPP in universities: project research |

| Japan | The OPIR makes recommendations to political decision-makers The OPIR collaborates with academic research | - Strong state commitment - Use of innovative technologies for sequencing - Register/platform compatible with international standards |

Based on a few key criteria necessary for the development of a national system, we have compared the organization of each country and highlighted several specific characteristics.

(a) The government steers and funds all the programs, sometimes in association with private partners, in Germany with the ACHSE patient organization and in Canada with the Genome Canada structure.

(b) Significant disparities can be seen in the establishment of centers of expertise:

In Canada and the United States, multidisciplinary research consortia are funded by the state, whereas centers of expertise are housed in hospitals that are mainly private.

In Spain, the SpainUDP translational program for undiagnosed diseases is coordinated with the 19 centers of expertise.

In France, 400 reference centers look after patients and organize their healthcare, while 23 Health Networks for Rare Diseases bring together the players involved in one or more diseases.

In Japan, the centers of expertise are associated with clinical investigation centers.

In the UK, the government prioritizes investments in patient care and empowerment.

Finally, the number of centers is not proportional to population density.

(c) In terms of genomics, Canada and Japan are pioneers, Japan as early as 1972 with the Nan-Byo program, and Canada from 2000 with Genome Canada.

(d) International collaboration is a key benefit that is very much a part of the system in North America, Spain, and Japan.

(e) The state of development of national registry programs varies considerably. Canada, Spain, the United States, France, and Japan have operational tools. Canada, Spain, and the United States are connected to the UNDI consortium, sharing their data for research purposes. UNDI partner countries are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Hungary, India, Italy, Korea, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Thailand, Turkey, and the United States.

(f) Depending on the country, industrial partners may be involved at different stages of the plan:

- In Germany and the United Kingdom, the public-private centers specialized in a particular field, such as the Fraunhofer ITMP and the CGT Catapult, seek to promote industrial partnerships.

- In Canada, private partners are associated with the state from the outset.

- In Spain and France, private partnerships are mainly based on public university hospital campuses. In France, the launch of University Hospital Institutes (IHU) in 2010, jointly funded by the government and industry, encourages public/private partnerships.

- In the United States, the TRND co-funds the development of drugs with manufacturers until an IND is filed. Moreover, 80% of university research (all fields) is funded by private partnerships.

- In Japan, OPIR makes policy recommendations, supports research projects and sets up joint projects with third parties.

In conclusion, inspired by the successes of the different organizations of the countries previously presented, an optimal approach could be suggested [Table 3], avoiding pitfalls. In this approach:

Proposed outline for an optimal approach

| Purpose | Outlining an optimal approach | Models to be adopted |

| Steering | State + Private funding partners | Canada |

| Regulations | (1) Accelerated regulations for bringing products to the market (2) Harmonization in the number of neonatal tests (3) Harmonization in drug prices | France: Act of 2019: Temporary authorization for use (ATU) and cohort temporary authorization for use (ATUc) (1) USA: new FDA regulations in 2012 (1) |

| Funding & coordination | State, industry, patient organizations | Germany: patient organization (ACHSE) Canada: genome Canada Japan: OPIR |

| Centers of expertise | (1) Structured implementation, covering the whole country (2) Investing in patient care and empowerment | France: CRMR and the Rare Diseases Research Networks (1) United Kingdom: HSSs (1) (2) |

| Gene identification | (1) International collaboration (2) Systematic use of innovative technologies for sequencing (3) High-throughput sequencing platforms | Spain: SpainUDP (1) (3) France: France Genome 2025 (2) (3) Canada: Genome Canada, C4R (1) (2) (3) USA: UDN (1) (2) (3) Japan: IRUD (1) (2) (3) |

| Register | Use of international standards such as the Automatable Discovery and Access Matrix defined by the IRDiRC | Spain: SpainRDR Canada: PhenomeCentral. USA: GARD Japan: IRUD data center |

| Public/private partnership | (1) Agency for innovation and technology transfer, specializing in rare diseases, funded by the state and manufacturers (2) Center for the production of innovative products accessible to manufacturers | Germany: Fraunhofer dedicated to translational medicine and pharmacology (1) United Kingdom: CGT Catapult (1) (2) USA: TRND (1) |

√ The government and private partners (on a pro rata basis according to their participation) would steer and fund the system, in the same way as with the Genome Canada model.

√ The organization of the centers of expertise would be based on the French model, with increased financial support for patient empowerment (UK).

√ In terms of genomics, the emphasis would be placed on international collaboration and information sharing, with involvement in international consortia such as Care4Rare.

√ The ongoing development of national registries would be based on international standards, for connection to the European and international platforms currently under development.

√ The involvement of manufacturers from the outset in order to favor partnerships (Canada). Furthermore, the results of the CGT Catapult in the United Kingdom underline the relevance of a specialized system dedicated to rare diseases. Finally, the business model of the French IHU has produced real economic benefits and deserves further development.

CONCLUSION

This work examined the different national plans and strategies dedicated to rare diseases in Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, France, Japan, Canada, and the United States. We were especially interested in the commitment of these countries, their healthcare and biomedical research system organization, their national legislation and their culture in terms of innovation and public-private partnerships. By concentrating the available information on the national plans and strategies, we were able to identify their strengths and divergences, and then define a possible optimal approach [Table 3].

It is important to stress that the 7 countries included in our work are not the only countries in Europe, East Asia, and North America to have established a national plan or strategy dedicated to rare diseases.

Indeed, within the EU, a total of 25 member states have already established a national plan or strategy [Figure 1], while only 3 of them are included in our work. Therefore, the optimal approach we have defined could certainly be refined, considering the potential successful organizations that are present in the 22 member states not included here. Additionally, the impact on European countries of the EU’s policy on rare diseases has not been discussed, but such an analysis could provide a complement to our optimal approach.

Using the same principle, the national plans and strategies for rare diseases established in East Asian and North American countries, which are not included in our work, could also refine the proposed optimal approach. Nevertheless, we believe that our work offers an important overview of successful national strategies and plans dedicated to rare diseases from which countries could potentially benefit.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

OrphanDev (https://www.orphan-dev.org/) is a French national network funded by the French Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (F-CRIN) aiming to bring solutions to patients suffering from rare diseases. The authors would like to thank F-CRIN for their support.

Authors’ contributions

Conducted the review: Trentesaux V

Contributed to discussion and manuscript writing: Cortial L, Nguyen C, Julkowska D, Cocqueel-Tiran F, Moliner AM, Blin O, Trentesaux V

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the F-CRIN.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2022.

REFERENCES

1. NAMSE. National action league for people with rare diseases. Available from: https://www.namse.de/english [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

2. Haase J, Wagner TOF, Storf H. se-atlas - the health service information platform for people with rare diseases : supporting research on medical care institutions and support groups. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2017;60:503-9.

3. Medical Informatics Initiative. About the initiative. Available from: https://www.medizininformatik-initiative.de/index.php/en/about-initiative [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

4. DZNE. New impetus for research on rare neurological disorders. Available from: https://www.dzne.de/en/news/press-releases/press/new-impetus-for-research-on-rare-neurological-disorders/ [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

5. Institute - Fraunhofer ITMP. Fraunhofer institute for translational medicine and pharmacology ITMP. Available from: https://www.itmp.fraunhofer.de/en/institute.html [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

6. Fraunhofer-Annual-Report-2019. Available from: https://www.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/zv/en/Publications/Annual-Report/2019/Fraunhofer-Annual-Report-2019.pdf [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

7. Pages - Our ISCIII Centres. Available from: https://eng.isciii.es/eng.isciii.es/QuienesSomos/CentrosPropios/Paginas/default.html [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

8. NHS commissioning. Highly specialised services. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/spec-services/highly-spec-services/ [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

9. Our Centres. The catapult network. Available from: https://catapult.org.uk/about-us/our-centres/ [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

10. Cell and gene therapy catapult - Annual Reviews. Available from: https://ct.catapult.org.uk/our-impact/annual-reviews [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

11. Construction completed on CGT Catapult expansion. Available from: https://ct.catapult.org.uk/news-media/manufacturing-news/construction-completed-expansion-phase-doubling-capacity [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

12. Genome Canada. Genome Canada’s role. Available from: https://www.genomecanada.ca/en/why-genomics/genome-canadas-role [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

13. Indigenous Health. The silent genomes project. Available from: https://www.indigenoushealthnh.ca/news/silent-genomes-project-indigenous-DNA [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

14. Rare diseases: models & mechanisms network. Available from: http://www.rare-diseases-catalyst-network.ca/about-the-network.html [Last accessed on 17 Jan 2022].

15. CARE for RARE. Available from: http://care4rare.ca [Last accessed on 17 Jan 2022].

16. Buske OJ, Girdea M, Dumitriu S, et al. PhenomeCentral: a portal for phenotypic and genotypic matchmaking of patients with rare genetic diseases. Hum Mutat. 2015;36:931-40.

17. Ontario genomics. What we do. Available from: https://www.ontariogenomics.ca/about-us/what-we-do/ [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

18. CORD. Now is the time: a strategy for rare diseases is a strategy for all Canadians. Available from: https://www.raredisorders.ca/content/uploads/CORD_Canada_RD_Strategy_22May15.pdf [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

19. Government of Canada. National strategy for drugs for rare diseases online engagement. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/programs/consultation-national-strategy-high-cost-drugs-rare-diseases-online-engagement.html [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

20. FDA. Developing Products for Rare Diseases & Conditions. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/industry/developing-products-rare-diseases-conditions [Last accessed on 17 Jan 2022].

21. Congressional Research Service. National institutes of health (NIH) funding: FY1996-FY2023. Available from: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43341.pdf [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

22. GARD. Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR) Brochure - Office of Rare Diseases Research. Available from: https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/asp/resources/ord_brochure.html [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

23. Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network. Available from: https://www.rarediseasesnetwork.org/ [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

24. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Rare diseases clinical research network (RDCRN). Available from: https://ncats.nih.gov/rdcrn [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

25. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Therapeutics for rare and neglected diseases (TRND). Available from: https://ncats.nih.gov/trnd [Last accessed on 18 Jan 2022].

26. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) - an NCATS Program. Available from: https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/ [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

27. National center for advancing translational sciences. Rare diseases registry program (RaDaR). Available from: https://ncats.nih.gov/radar [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

28. UDN. Undiagnosed diseases network. Available from: https://undiagnosed.hms.harvard.edu/ [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

29. Ito T. Patient groups’ advocacy activity and nanbyo act (The Iatric Services to Patients Suffering from Intractable Disease): from the view point of patient groups. J Health Care Soc. 2018;28:27-36.

30. Richter T, Nestler-Parr S, Babela R, et al.; International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Rare Disease Special Interest Group. Rare disease terminology and definitions-a systematic global review: report of the ISPOR rare disease special interest group. Value Health. 2015;18:906-14.

31. Adachi T, Kawamura K, Furusawa Y, et al. Japan’s initiative on rare and undiagnosed diseases (IRUD): towards an end to the diagnostic odyssey. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:1025-8.

32. Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. Practical research project for rare / intractable diseases. Available from: https://www.amed.go.jp/en/program/list/11/02/003.html [Last accessed on 23 May 2022].

33. RADDAR-J. RADDAR-J - Rare Disease Data Registry of Japan. Available from: https://www.raddarj.org/en/ [Last accessed on 18 Jan 2022].

34. IRDiRC. Automatable discovery and access. Available from: https://irdirc.org/activities/task-forces/automatable-discovery-and-access/ [Last accessed on 18 Jan 2022].

35. About OPIR. Office of pharmaceutical industry research. Available from: https://www.jpma.or.jp/opir/en/about/index.html [Last accessed on 18 Jan 2022].

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].