Artificial intelligence in forensic genetics: applications and ethical challenges

Abstract

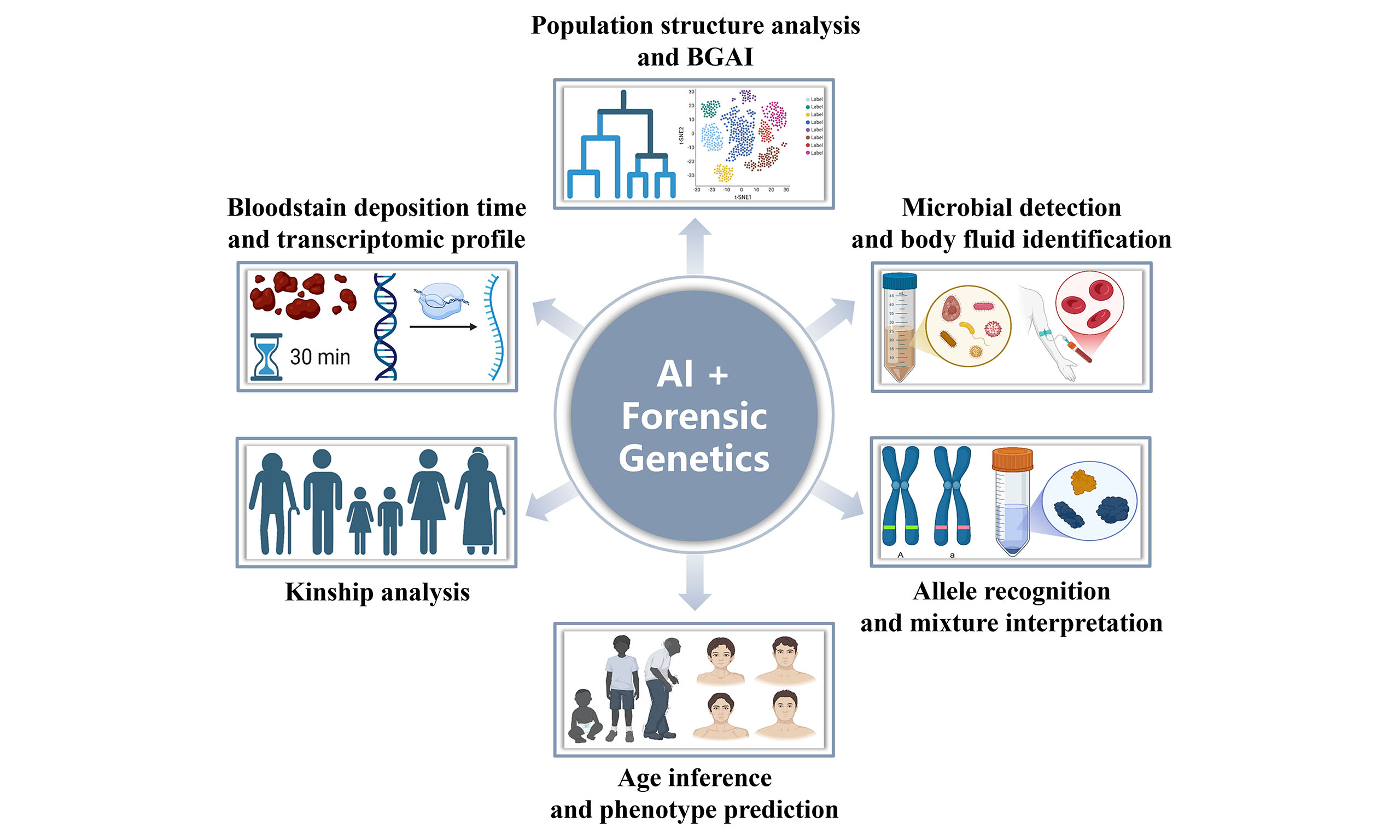

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming forensic genetics through groundbreaking applications in (1) population structure analysis and biogeographical ancestry inference; (2) microbial detection and body fluid identification; (3) allele recognition and mixture interpretation; (4) age inference and phenotype prediction, (5) kinship analysis; and (6) other emerging domains, such as bloodstain deposition time and transcriptomic analysis. While promising efficiency and enhanced accuracy, its integration also raises ethical, legal, and social concerns. This opinion piece critically explores both the promise and perils of AI in forensic genetics, calling for urgent action to (1) build secure and trustworthy AI systems; (2) develop agile and effective regulatory frameworks; (3) uphold ethical integrity and human-centered design; and (4) foster global collaboration to meet cross-border challenges. Together, these principles are essential to ensuring that AI’s integration into forensic science advances both technological progress and the pursuit of justice.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Forensic genetics has undergone a profound transformation, driven by advances in genomics, computational biology, and high-throughput sequencing technologies. Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML), now plays an increasingly pivotal role in decoding complex DNA profiles, facilitating individual identification, and supporting criminal investigations[1]. Yet, this technological progress is accompanied by a range of ethical and legal challenges that remain insufficiently addressed[2]. This article offers a critical examination of both the opportunities and the risks associated with AI in forensic genetics, advocating for a measured and ethically informed approach to its implementation. We conducted a comprehensive search of PubMed and Web of Science (WoS) for publications from the past five years using the query “All Fields = [(Artificial Intelligence) OR (Machine Learning)] AND (Forensic Genetics).” Drawing on recent technological developments and representative case studies, we assess the scientific potential of AI while highlighting the sociotechnical risks it introduces in this rapidly evolving domain.

TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATIONS AND FORENSIC APPLICATIONS

Population structure analysis and biogeographical ancestry inference (BGAI)

AI as an auxiliary tool is transforming the resolution at which human population structure and ancestry can be explored. In studies of Chinese and East Asian populations, AI frameworks now integrate diverse molecular markers, including ancestry informative single nucleotide polymorphisms (AISNPs)[3-5], X-chromosome insertion/deletion polymorphisms (X-InDels)[6], Y-chromosomal short tandem repeats (Y-STRs)[7-9], and Y-chromosomal single nucleotide polymorphisms (Y-SNPs)[10], together with advanced ML models such as extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost)[11-13], partial least squares discrimination analysis (PLS-DA)[14], and soft clustering[15]. Together, these methods overcome the long-standing limitations of traditional linear models, which relied on small marker sets and offered limited discriminative power. By automatically extracting key signals from large-scale genomic data, AI-driven models[16-26] achieve significantly improved precision in distinguishing closely related groups such as northern and southern Han Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans, as well as in tracing haplogroup and surname lineages. This shift marks a methodological leap from descriptive phylogenetic analyses to scalable, data-intensive inference, redefining how population diversity and ancestral origins are characterized across East Asia.

Microbial detection and body fluid identification

AI as an auxiliary tool is reshaping forensic microbiomics[27] and body fluid identification by enabling a multi-omics perspective. Traditional methods, which are limited by single biomarkers and low analytical resolution, are now being replaced by AI frameworks that harness ML and genetic algorithms to mine high-dimensional microbiome and molecular data. By integrating microbial signatures from 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing[28,29], skin and saliva profiles[30-34], and environmental samples such as burial soil and water[35,36], alongside multi-omics markers including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)[37], transfer RNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs)[38], microRNAs[39], mesessenger RNAs (mRNAs)[40,41], and cytosine-guanine (CpG) methylation[42], these approaches achieve unprecedented sensitivity and specificity. AI-driven models now deliver precise discrimination of body fluid origins[43-45], accurate estimation of postmortem intervals (PMI)[46,47], and geographic traceability[48,49]. With their strong robustness and interpretability, AI-driven frameworks significantly outperform conventional statistical models.

Allele recognition and DNA mixture interpretation

AI as an auxiliary tool is redefining the precision and automation of allele recognition[50] and mixture interpretation[51] in forensic DNA analysis. By integrating interpretable neural networks[52,53] and deep learning (DL) architectures[54], AI systems can now resolve low-template DNA, complex electropherograms, and highly mixed biological samples[55,56] with significantly improved accuracy. These models automatically extract informative alleles, infer the number and identity of contributors[57-60] within DNA mixtures, and leverage molecular barcoding and probabilistic genotyping[61] to enhance analytical confidence and reproducibility. Overcoming the subjective thresholds and limited resolution of traditional statistical approaches, AI-driven frameworks deliver objective and high-throughput solutions for genetic evidence interpretation. This transition marks a fundamental step toward fully automated, data-driven forensic genetics.

Age inference and phenotype prediction

AI as an auxiliary tool is expanding the scope of forensic age inference[62] and phenotype prediction[63,64] through multimodal data fusion and nonlinear modeling. Traditional linear or single-marker frameworks often fail to capture the intricate molecular patterns underlying biological aging and external traits. AI-driven systems now integrate DNA methylation[65-72], non-coding RNA[73-75], and other omics-level features[76] using advanced ML and neural network architectures, enabling robust modeling even with limited samples. These approaches markedly enhance the accuracy of age prediction from blood, wound[77], and other forensic materials, accelerating the development of intelligent epigenetic clocks[76,78]. Beyond age inference, AI models demonstrate exceptional capacity to predict eye color[79-81] and reconstruct three-dimensional facial morphology[82,83], thereby surpassing the explanatory power of conventional genotype-phenotype association models. By addressing the complexity of forensic datasets, AI establishes a scalable and high-precision framework for molecular-level human identification.

Kinship analysis

AI as an auxiliary tool is strengthening forensic kinship analysis by integrating precision inference with privacy-preserving computation. Conventional short tandem repeats (STRs)-based approaches often struggle to distinguish close relatives, resolve complex familial structures, or protect sensitive genetic data. AI frameworks now fuse multilayered evidence, including rapidly mutating Y-STR profiles[84-86], facial imagery[87], and other biometric or genomic cues, together with homomorphic encryption[88] and related privacy-preserving technologies. This integration enables high-resolution identification of complex relationships while maintaining the confidentiality of underlying genetic information. Beyond improving the discrimination of paternal lineages[84-86], AI models have demonstrated the ability to detect incestuous relations[89], which greatly improves the efficiency achieved through manual interpretation or classical statistical methods. By uniting accuracy with security, AI-driven kinship analysis establishes a new paradigm for reliable, ethically sound forensic genetics.

Other emerging domains

AI as an auxiliary tool is empowering temporal inference in forensic genetics by enhancing both its precision and temporal resolution. ML models that integrate rhythmic mRNA expression profiles now enable the precise estimation of bloodstain deposition time[90,91] within a 24-h window, overcoming the static and target-dependent constraints of conventional capillary electrophoresis (CE) assays. Similarly, AI-powered transcriptomic analysis can decode complex temporal signals embedded in molecules such as microRNAs, markedly improving PMI[92]. By capturing dynamic biomarker fluctuations, these approaches address one of the central challenges in forensic genetics, providing a more reliable and biologically grounded temporal dimension to evidentiary analysis.

CURRENT CHALLENGES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Scientific and technical aspects

Forensic AI systems have technical limitations such as algorithmic bias, model opacity and vulnerability to adversarial manipulation[93]; models trained on Eurocentric datasets often misclassify underrepresented populations, and the lack of transparency in “black box” algorithms undermines judicial credibility, requiring explainable AI (XAI) and robust cybersecurity for traceability and reliability[94]. Future progress should emphasize explainability and accountability: adopting XAI models such as decision trees and Bayesian networks[95], using hybrid systems with human oversight and automation, applying validation protocols assessing accuracy and interpretability, and expanding datasets via inclusive genomic initiatives can boost transparency, evidentiary reliability and fairness[96].

Governance and regulatory aspects

The rapid adoption of AI has outpaced the creation of dedicated forensic legislation. Most jurisdictions lack clear rules on accountability, admissibility and data governance. While frameworks such as the European Union (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) stress explicit consent, such safeguards are often overridden in the name of public safety, causing regulatory ambiguity[97]. Robust governance frameworks need to include transparency requirements and back privacy-preserving technologies such as federated learning and homomorphic encryption[98]. Dynamic consent mechanisms should enable individuals to maintain continuous control over their genetic data, matching data governance with changing ethical and legal expectations. Effective oversight requires flexible, risk-adaptive regulatory frameworks supported by mandatory auditing, certification and clearly defined legal responsibilities, and establishing accountability mechanisms is key to ensuring compliance and public trust[99].

Ethical and societal aspects

Extensive use of public and commercial genetic databases sparks concerns about informed consent, data reuse and privacy. Incidents such as unauthorized access to 23andMe data highlight the urgency of transparent data stewardship and ethical oversight[100]. Ethical deployment of such databases should follow a “privacy by default” principle, reducing exposure risks at every analytic stage. Prioritizing data equity and ensuring responsible use of population-scale genetic resources are essential to maintain public trust and fairness[101]. Meanwhile, AI deployment in this field must uphold fairness, inclusivity and human dignity, with strategies including systematic bias detection, fairness assurance protocols, proactive public engagement, relevant education and human-centered system design[93].

Global collaboration aspects

Disparities in legal, ethical and technical standards across regions hinder equitable, consistent AI application. International bodies such as the International Society of Forensic Genetics (ISFG) need to promote unified guidelines, fairness audits and cross-border cooperation, including creating harmonized standards, sharing safety research findings in non-competitive AI domains and establishing global monitoring networks to ensure responsible global deployment[102]. Bridging gaps among scientists, forensic practitioners, legal experts and ethicists requires sustained cross-sector engagement; continuous multistakeholder dialogue, joint training and collaborative policy efforts can drive socially responsible, globally consistent implementation of forensic AI[103].

CONCLUSION

AI is profoundly reshaping forensic genetics across a spectrum of critical applications. These include population structure analysis, BGAI, microbial detection, body fluid identification, allele recognition, mixture interpretation, age inference, phenotype prediction, kinship analysis, and other emerging frontiers such as bloodstain deposition time and transcriptomic analysis. By integrating multi-omic, imaging, and dynamic biological signals, AI transforms static genetic profiling into a multidimensional and predictive science. Yet the power of these technologies also demands foresight: data security, algorithmic bias, and ethical accountability must evolve in parallel with technical innovation. The future of forensic AI depends not only on model accuracy but also on transparency, robustness, and governance by design, which embeds ethical and legal safeguards from the outset. Through interdisciplinary collaboration, open international standards, and public engagement, AI can mature into a responsible scientific partner that enhances human identification and understanding, ultimately strengthening both the rigor and the humanity of modern forensic genetics.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Prof. Chengtao Li and Prof. Suhua Zhang from the School of Forensic Medicine and Science, Fudan University, for their valuable advice. The author gratefully acknowledges the English language editing support and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and valuable suggestions. The Graphical Abstract was created with BioRender. Zhang, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/pauwnin.

Authors’ contributions

The author contributed solely to the article.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFC3306701).

Conflicts of interest

The author declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Barash M, McNevin D, Fedorenko V, Giverts P. Machine learning applications in forensic DNA profiling: a critical review. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2024;69:102994.

2. Gutiérrez-Hurtado IA, García-Acéves ME, Puga-Carrillo Y, et al. Past, present and future perspectives of forensic genetics. Biomolecules. 2025;15:713.

3. Chen J, Huang Y, Zhong J, Wang M, He G, Yan J. Bioinformatic insights into five Chinese population substructures inferred from the East Asian-specific AISNP panel. BMC Genom. 2025;26:748.

4. Chen J, Zhang H, Yang M, et al. Genomic formation of Tibeto-Burman speaking populations in Guizhou, Southwest China. BMC Genom. 2023;24:672.

5. Gu JQ, Zhao H, Guo XY, Sun HY, Xu JY, Wei YL. A high-performance SNP panel developed by machine-learning approaches for characterizing genetic differences of Southern and Northern Han Chinese, Korean, and Japanese individuals. Electrophoresis. 2022;43:1183-92.

6. Huang X, Gu C, Ran Q, et al. Exploring the forensic effectiveness and population genetic differentiation in Guizhou Miao and Bouyei group by the self-constructed panel of X chromosomal multi-insertion/deletions. BMC Genom. 2024;25:1185.

7. Fan GY, Jiang DZ, Jiang YH, Song W, He YY, Wuo NA. Phylogenetic analyses of 41 Y-STRs and machine learning-based haplogroup prediction in the Qingdao Han population from Shandong province, Eastern China. Ann Hum Biol. 2023;50:35-41.

8. Fan GY. Assessing the factors influencing the performance of machine learning for classifying haplogroups from Y-STR haplotypes. Forensic Sci Int. 2022;340:111466.

9. Jin XY, Fang YT, Cui W, et al. Development of the decision tree model for distinguishing individuals of Chinese four surnames from Zhanjiang Han population based on Y-STR haplotypes. Leg Med. 2021;49:101848.

10. Yin C, He Z, Wang Y, et al. Improving the regional Y-STR haplotype resolution utilizing haplogroup-determining Y-SNPs and the application of machine learning in Y-SNP haplogroup prediction in a forensic Y-STR database: a pilot study on male Chinese Yunnan Zhaoyang Han population. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2022;57:102659.

11. Wang C, Wang S, Zhao Y, et al. A biogeographical ancestry inference pipeline using PCA-XGBoost model and its application in Asian populations. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2025;77:103239.

12. Šorgić D, Stefanović A, Keckarević D, Popović M. XGBoost as a reliable machine learning tool for predicting ancestry using autosomal STR profiles - proof of method. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2025;76:103183.

13. Wan W, Zhang H, Ren Z, et al. Systematic selection of ancestry informative SNPs for differentiating Han, Japanese, Dai, and Kinh populations. Electrophoresis. 2023;44:1405-13.

14. Pilli E, Morelli S, Poggiali B, Alladio E. Biogeographical ancestry, variable selection, and PLS-DA method: a new panel to assess ancestry in forensic samples via MPS technology. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2023;62:102806.

15. Burger KE, Klepper S, von Luxburg U, Baumdicker F. Inferring ancestry with the hierarchical soft clustering approach tangleGen. Genome Res. 2024;34:2244-55.

16. Heinzel CS, Purucker L, Hutter F, Pfaffelhuber P. Advancing biogeographical ancestry predictions through machine learning. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2025;79:103290.

17. You H, Lee SD, Cho S. A machine learning approach for estimating Eastern Asian origins from massive screening of Y chromosomal short tandem repeats polymorphisms. Int J Legal Med. 2025;139:531-40.

18. Khan MF, Rakha A, Munawar A, et al. Genetic diversity and forensic utility of X-STR loci in punjabi and kashmiri populations: insights into population structure and ancestry. Genes. 2024;15:1384.

19. Afkanpour M, Momeni M, Tabrizi AA, Tabesh H. A haplogroup-based methodology for assigning individuals to geographical regions using Y-STR data. Forensic Sci Int. 2024;365:112260.

20. Liu L, Li S, Cui W, et al. Ancestry analysis using a self-developed 56 AIM-InDel loci and machine learning methods. Forensic Sci Int. 2024;361:112065.

21. Kloska A, Giełczyk A, Grzybowski T, et al. A machine-learning-based approach to prediction of biogeographic ancestry within Europe. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:15095.

22. Chen M, Cui W, Bai X, et al. Comprehensive evaluations of individual discrimination, kinship analysis, genetic relationship exploration and biogeographic origin prediction in Chinese Dongxiang group by a 60-plex DIP panel. Hereditas. 2023;160:14.

23. Gorin I, Balanovsky O, Kozlov O, et al. Determining the area of ancestral origin for individuals from North Eurasia based on 5,229 SNP markers. Front Genet. 2022;13:902309.

24. Alladio E, Poggiali B, Cosenza G, Pilli E. Multivariate statistical approach and machine learning for the evaluation of biogeographical ancestry inference in the forensic field. Sci Rep. 2022;12:8974.

25. Sun K, Yao Y, Yun L, et al. Application of machine learning for ancestry inference using multi-InDel markers. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2022;59:102702.

26. Jin X, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Li Y, Chen C, Wang H. Autosomal deletion/insertion polymorphisms for global stratification analyses and ancestry origin inferences of different continental populations by machine learning methods. Electrophoresis. 2021;42:1473-9.

27. Lei FZ, Chen M, Mei SY, Fang YT, Zhu BF. New advances, challenges and opportunities in forensic applications of microbiomics. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2022;38:625-39.

28. Tao R, Wang X, Zhen X, et al. Skin microbiome alterations in heroin users revealed by full-length 16S rRNA sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2025;25:461.

29. Liao L, Sun Y, Huang L, Ye L, Chen L, Shen M. A novel approach for exploring the regional features of vaginal fluids based on microbial relative abundance and alpha diversity. J Forensic Leg Med. 2023;100:102615.

30. Wang X, Yuan X, Lin Y, et al. Exploratory study on source identification of saliva stain and its TsD inference based on the microbial relative and absolute abundance. Int J Legal Med. 2025;139:2063-75.

31. Huang L, Du J, Ye L, et al. Species level and SNP profiling of skin microbiome improve the specificity in identifying forensic fluid and individual. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2025;78:103256.

32. Yao H, Wang Y, Wang S, et al. A multiplex microbial profiling system for the identification of the source of body fluid and skin samples. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2024;73:103124.

33. Huang L, Huang H, Liang X, et al. Skin locations inference and body fluid identification from skin microbial patterns for forensic applications. Forensic Sci Int. 2024;362:112152.

34. Sherier AJ, Woerner AE, Budowle B. Population informative markers selected using wright's fixation index and machine learning improves human identification using the skin microbiome. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2021;87:e0120821.

35. Su Q, Zhang X, Chen X, et al. Microbial community profiling for forensic drowning diagnosis across locations and submersion times. BMC Microbiol. 2025;25:244.

36. Su Q, Zhang X, Chen X, et al. Integrating microbial profiling and machine learning for inference of drowning sites: a forensic investigation in the Northwest River. Microbiol Spectr. 2025;13:e0132124.

37. Sherier AJ, Woerner AE, Budowle B. Determining informative microbial single nucleotide polymorphisms for human identification. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2022;88:e0005222.

38. Li Z, Zhou B, Su M, et al. Quantitative differential analysis of tsRNAs for forensic body fluid identification: RT-qPCR-based discrimination derived from epithelial cell fluids screening. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2026;80:103338.

39. Li S, Liu J, Xu W, et al. A multi-class support vector machine classification model based on 14 microRNAs for forensic body fluid identification. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2025;75:103180.

40. Xiao Y, Tan M, Song J, et al. Developmental validation of an mRNA kit: a 5-dye multiplex assay designed for body-fluid identification. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2024;71:103045.

41. Ypma RJF, Maaskant-van Wijk PA, Gill R, Sjerps M, van den Berge M. Calculating LRs for presence of body fluids from mRNA assay data in mixtures. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2021;52:102455.

42. Zhao M, Cai M, Lei F, et al. AI-driven feature selection and epigenetic pattern analysis: a screening strategy of CpGs validated by pyrosequencing for body fluid identification. Forensic Sci Int. 2025;367:112339.

43. Kim S, Lee HC, Sim JE, Park SJ, Oh HH. Bacterial profile-based body fluid identification using a machine learning approach. Genes Genom. 2025;47:87-98.

44. Swayambhu M, Gysi M, Haas C, et al. Standardizing a microbiome pipeline for body fluid identification from complex crime scene stains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2025;91:e0187124.

45. Wohlfahrt D, Tan-Torres AL, Green R, et al. A bacterial signature-based method for the identification of seven forensically relevant human body fluids. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2023;65:102865.

46. Mason AR, McKee-Zech HS, Steadman DW, DeBruyn JM. Environmental predictors impact microbial-based postmortem interval (PMI) estimation models within human decomposition soils. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0311906.

47. Cui C, Song Y, Mao D, et al. Predicting the postmortem interval based on gravesoil microbiome data and a random forest model. Microorganisms. 2022;11:56.

48. Lei Y, Li M, Zhang H, et al. Comparative analysis of the human microbiome from four different regions of China and machine learning-based geographical inference. mSphere. 2025;10:e0067224.

49. Bhattacharya C, Tierney BT, Ryon KA, et al. Supervised machine learning enables geospatial microbial provenance. Genes. 2022;13:1914.

50. Tan M, Tan Y, Jiang H, et al. Explainable artificial intelligence in forensic DNA analysis: alleles identification in challenging electropherograms using supervised machine learning methods. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2025;78:103289.

51. Crysup B, Mandape S, King JL, Muenzler M, Kapema KB, Woerner AE. Using unique molecular identifiers to improve allele calling in low-template mixtures. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2023;63:102807.

52. Volgin L, Taylor D, Bright JA, Lin MH. Validation of a neural network approach for STR typing to replace human reading. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2021;55:102591.

53. Valtl J, Mönich UJ, Lun DS, Kelley J, Grgicak CM. A series of developmental validation tests for number of contributors platforms: exemplars using NOCIt and a neural network. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2021;54:102556.

54. Kruijver M, Kelly H, Cheng K, et al. Estimating the number of contributors to a DNA profile using decision trees. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2021;50:102407.

55. Gu C, Huo W, Huang X, et al. Developmental and validation of a novel small and high-efficient panel of microhaplotypes for forensic genetics by the next generation sequencing. BMC Genom. 2024;25:958.

56. Fan QW, Li L, Yang HL, et al. A bibliometric and visual analysis of the current status and trends of forensic mixed stain research. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2024;40:20-9.

57. Wang H, Zhu Q, Huang Y, et al. Using simulated microhaplotype genotyping data to evaluate the value of machine learning algorithms for inferring DNA mixture contributor numbers. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2024;69:103008.

58. Veldhuis MS, Ariëns S, Ypma RJF, Abeel T, Benschop CCG. Explainable artificial intelligence in forensics: realistic explanations for number of contributor predictions of DNA profiles. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2022;56:102632.

59. Yang J, Chen J, Ji Q, et al. A highly polymorphic panel of 40-plex microhaplotypes for the Chinese Han population and its application in estimating the number of contributors in DNA mixtures. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2022;56:102600.

60. Phan NN, Chattopadhyay A, Lee TT, et al. High-performance deep learning pipeline predicts individuals in mixtures of DNA using sequencing data. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22:bbab283.

61. Taylor D, Buckleton J. Combining artificial neural network classification with fully continuous probabilistic genotyping to remove the need for an analytical threshold and electropherogram reading. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2023;62:102787.

62. Huang YH, Liang WB, Jian H, Qu SQ. Modeling methods and influencing factors for age estimation based on DNA methylation. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2023;39:601-7.

63. Pośpiech E, Teisseyre P, Mielniczuk J, Branicki W. Predicting physical appearance from DNA data-towards genomic solutions. Genes. 2022;13:121.

64. Katsara MA, Branicki W, Walsh S, Kayser M, Nothnagel M; VISAGE Consortium. Evaluation of supervised machine-learning methods for predicting appearance traits from DNA. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2021;53:102507.

65. Gao N, Li J, Yang F, et al. Forensic age estimation from blood samples by combining DNA methylation and MicroRNA markers using droplet digital PCR. Electrophoresis. 2025;46:424-32.

66. Refn MR, Kampmann ML, Vyöni A, et al. Independent evaluation of an 11-CpG panel for age estimation in blood. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2025;76:103214.

67. Ji Z, Xing Y, Li J, et al. Male-specific age prediction based on Y-chromosome DNA methylation with blood using pyrosequencing. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2024;71:103050.

68. Varshavsky M, Harari G, Glaser B, Dor Y, Shemer R, Kaplan T. Accurate age prediction from blood using a small set of DNA methylation sites and a cohort-based machine learning algorithm. Cell Rep Methods. 2023;3:100567.

69. Aliferi A, Ballard D. Predicting chronological age from DNA methylation data: a machine learning approach for small datasets and limited predictors. In: Guan W, editor. Epigenome-wide association studies. New York, US: Springer; 2022. pp. 187-200.

70. Aliferi A, Sundaram S, Ballard D, et al. Combining current knowledge on DNA methylation-based age estimation towards the development of a superior forensic DNA intelligence tool. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2022;57:102637.

71. Thong Z, Tan JYY, Loo ES, Phua YW, Chan XLS, Syn CK. Artificial neural network, predictor variables and sensitivity threshold for DNA methylation-based age prediction using blood samples. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1744.

72. Lau PY, Fung WK. Evaluation of marker selection methods and statistical models for chronological age prediction based on DNA methylation. Leg Med. 2020;47:101744.

73. Fang C, Zhou P, Li R, et al. Development of a novel forensic age estimation strategy for aged blood samples by combining piRNA and miRNA markers. Int J Legal Med. 2023;137:1327-35.

74. Wang J, Zhang H, Wang C, et al. Forensic age estimation from human blood using age-related microRNAs and circular RNAs markers. Front Genet. 2022;13:1031806.

75. Wang J, Wang C, Wei Y, et al. Circular RNA as a potential biomarker for forensic age prediction. Front Genet. 2022;13:825443.

76. Paparazzo E, Lagani V, Geracitano S, et al. An ELOVL2-based epigenetic clock for forensic age prediction: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:2254.

77. Ma XY, Cheng H, Zhang ZD, Li YM, Zhao D. Research progress of metabolomics techniques combined with machine learning algorithm in wound age estimation. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2023;39:596-600.

78. Freire-Aradas A, Girón-Santamaría L, Mosquera-Miguel A, et al. A common epigenetic clock from childhood to old age. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2022;60:102743.

79. Behrens LMP, Gonçalves CEI, da Silva Fernandes G, et al. BR-FDP-EYE: brazilian forensic DNA eye phenotyping. Forensic Sci Int. 2025;377:112593.

80. Kukla-Bartoszek M, Teisseyre P, Pośpiech E, et al. Searching for improvements in predicting human eye colour from DNA. Int J Legal Med. 2021;135:2175-87.

81. Martínez CA, Hohl DM, Gutiérrez MLA, et al. DNA-based prediction of eye color in Latin American population applying Machine Learning models. Comput Biol Med. 2025;194:110404.

82. Wang X, Wei S, Zhao Z, Luo X, Song F, Li Y. 3D-3D superimposition techniques in personal identification: a ten-year systematic literature review. Forensic Sci Int. 2024;365:112271.

83. Jiao M, Li J, Zhong B, et al. De novo reconstruction of 3D human facial images from DNA sequence. Adv Sci. 2025;12:e2414507.

84. Sun C, Zhang Z, Wang X, et al. Construction of a novel 5-dye fluorescent multiplex system with 30 Y-STRs for patrilineal relationship prediction. Electrophoresis. 2025.

85. Ralf A, van Wersch B, Montiel González D, Kayser M. Male pedigree toolbox: a versatile software for Y-STR data analyses. Genes. 2024;15:227.

86. Ralf A, Montiel González D, Zandstra D, et al. Large-scale pedigree analysis highlights rapidly mutating Y-chromosomal short tandem repeats for differentiating patrilineal relatives and predicting their degrees of consanguinity. Hum Genet. 2023;142:145-60.

87. Yu J, Jin X, Du W, et al. Unveiling facial kinship: the BioKinVis dataset for facial kinship verification and genetic association studies. Electrophoresis. 2024;45:794-804.

88. Souza FDM, de Lassus H, Cammarota R. Private detection of relatives in forensic genomics using homomorphic encryption. BMC Med Genom. 2024;17:273.

89. Šorgić D, Stefanović A, Popović M, Keckarević D. From genetic data to kinship clarity: employing machine learning for detecting incestuous relations. Front Genet. 2025;16:1578581.

90. Fonneløp AE, Hänggi NV, Derevlean CC, Bleka Ø, Haas C. A CE-based mRNA profiling method including six targets to estimate the time since deposition of blood stains. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2025;77:103240.

91. Cheng F, Li W, Ji Z, et al. Estimation of bloodstain deposition time within a 24-h day-night cycle with rhythmic mRNA based on a machine learning algorithm. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2023;66:102910.

92. Lee H, Lee EJ, Park K, et al. MicroRNA transcriptome analysis for post-mortem interval estimation. Forensic Sci Int. 2025;370:112473.

93. Marsico F, Amigo M. Ethical and security challenges in AI for forensic genetics: from bias to adversarial attacks. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2025;76:103225.

94. Hall SW, Sakzad A, Choo KR. Explainable artificial intelligence for digital forensics. WIREs Forensic Sci. 2022;4:e1434.

95. Solanke AA. Explainable digital forensics AI: towards mitigating distrust in AI-based digital forensics analysis using interpretable models. Forens Sci Int. 2022;42:301403.

96. Pasipamire N, Muroyiwa A. Navigating algorithm bias in AI: ensuring fairness and trust in Africa. Front Res Metr Anal. 2024;9:1486600.

97. Bharati DR. Legal and ethical considerations in the use of digital forensics by law enforcement: a multi-jurisdictional study. SSRN J. 2020.

98. Calvino G, Peconi C, Strafella C, et al. Federated learning: breaking down barriers in global genomic research. Genes. 2024;15:1650.

99. D'Amato ME, Joly Y, Lynch V, Machado H, Scudder N, Zieger M. Ethical considerations for forensic genetic frequency databases: first report conception and development. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2024;71:103053.

100. Raz AE, Niemiec E, Howard HC, Sterckx S, Cockbain J, Prainsack B. Transparency, consent and trust in the use of customers' data by an online genetic testing company: an Exploratory survey among 23andMe users. New Genet Soc. 2020;39:459-82.

101. Ferrara E. Fairness and bias in artificial intelligence: a brief survey of sources, impacts, and mitigation strategies. Sci. 2024;6:3.

102. Ypma RJ, Ramos D, Meuwly DJAIiFS. AI-based forensic evaluation in court: the desirability of explanation and the necessity of validation. In Geradts Z, Franke K, editors, Artificial intelligence (AI) in forensic sciences. Wiley. 2023. Available from: https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/ai-based-forensic-evaluation-in-court-the-desirability-of-explana/ [Last accessed on 3 Dec 2025].

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].