The value of ctDNA tumor fraction in interpreting negative liquid biopsy results

Abstract

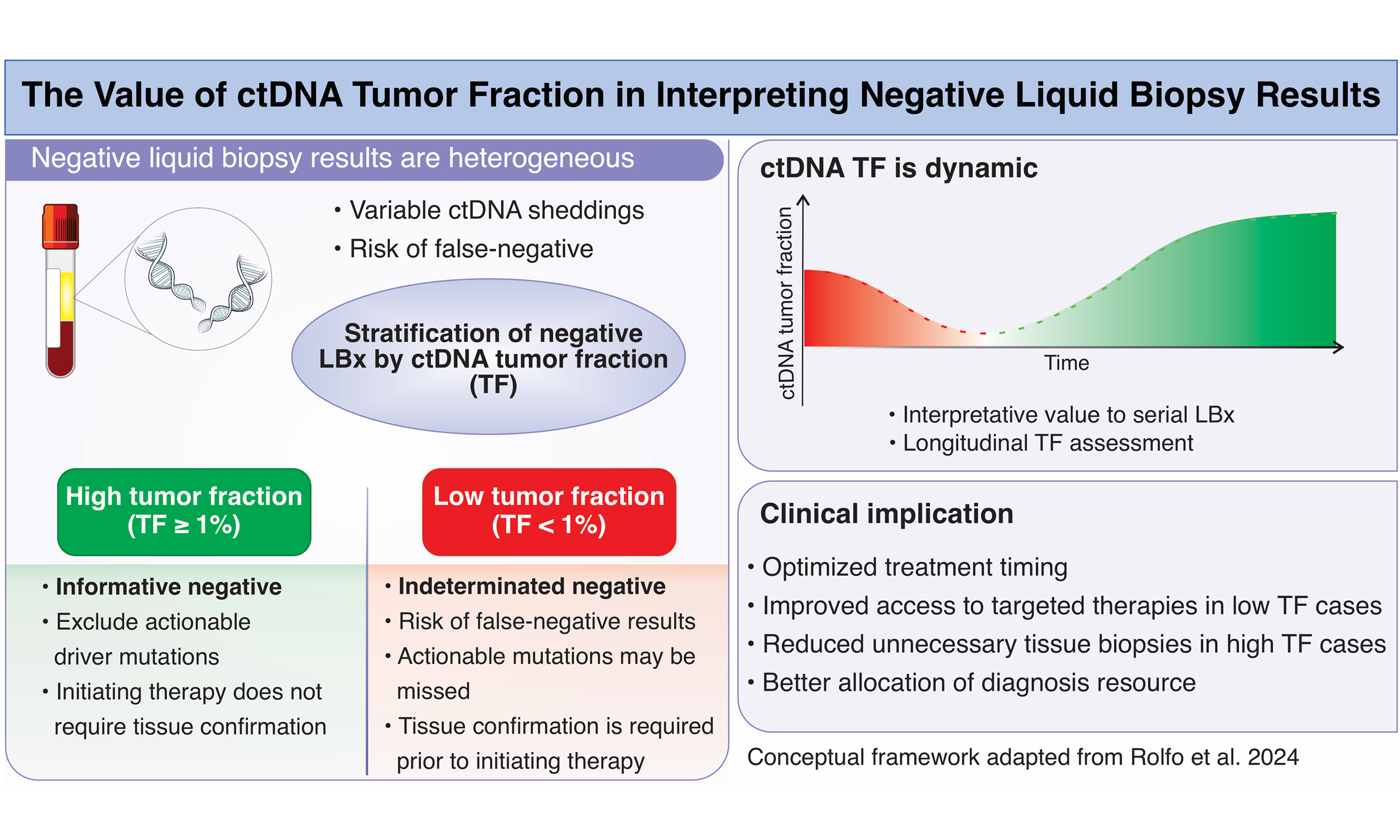

Liquid biopsy (LBx) has emerged as a powerful, non-invasive tool for genomic profiling in oncology, yet the interpretation of negative results remains a critical challenge. In their recent study, Rolfo et al. propose that the measurement of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) tumor fraction (TF) can help distinguish between true negatives and indeterminate results that require confirmatory tissue biopsy. Their analysis, based on large real-world datasets, demonstrates that patients with ctDNA TF ≥ 1% are unlikely to harbor undetected actionable driver mutations, whereas those with TF < 1% frequently benefit from reflex tissue testing. This commentary builds upon those findings by discussing their clinical relevance, strengths, limitations, and broader implications for clinical practice. In this commentary, we critically evaluate the study, situating it within the wider context of precision oncology, highlighting its clinical implications, potential limitations, and opportunities for future integration into cancer care.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The field of molecular oncology has rapidly advanced due to the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS), which allows comprehensive characterization of tumor genomes[1]. Liquid biopsy (LBx), based on the analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), has emerged as a minimally invasive and repeatable alternative that provides dynamic insights into tumor genomics[2,3]. The ctDNA tumor fraction (TF), defined as the proportion of total cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in plasma that originates from tumor cells, provides a quantitative measure of tumor burden and can inform the reliability of LBx results[2]. Traditionally, genomic profiling has relied on tissue biopsy (TBx), a procedure often associated with significant limitations, including invasiveness, procedural risks, limited tissue availability, and delays in obtaining results[4]. LBx addresses many of these issues, but it presents its own challenge: interpreting negative results. Unlike tissue-based assays, which usually provide sufficient tumor material, LBx depends on variable ctDNA shedding into the bloodstream[5]. Therefore, a negative result may either indicate the true absence of a driver mutation or a false negative due to inadequate ctDNA content in the sample[6]. Regulatory agencies, including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), recommend reflex TBx for negative LBx results, particularly in tumor types where molecular drivers guide therapy[7].

LBx is most widely used in non - small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a disease in which multiple targetable alterations - including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), ROS1 proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (ROS1), B-Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine kinase (BRAF), mesenchymal epithelial transition (MET), rearranged during transfection (RET), and Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) G12C mutations - determine first-line therapy[8]. In this context, the turnaround time of molecular profiling is directly associated with patient outcomes: faster access to results allows for earlier initiation of targeted therapy, which has been shown to improve survival[9]. Without additional context, a negative result cannot be assumed to reflect the tumor’s genomic reality. False negatives occur frequently in patients with low tumor burden, indolent disease, or non-shedding tumors[10]. Rolfo et al.[11] address this challenge by proposing ctDNA TF as a quantitative biomarker to stratify the reliability of negative LBx results. Their study showed that approximately 37% of NSCLC patients with negative LBx were later found to harbor actionable drivers in tissue biopsies, highlighting the importance of stratifying negative results in clinical decision-making[11].

To enhance accuracy, Rolfo et al.[11] developed an algorithm for TF estimation that integrates multiple genomic features, including aneuploidy patterns, variant allele frequency of somatic mutations, canonical driver alterations, exclusion of germline variants and clonal hematopoiesis signals through multiomic patterns. This approach enhances accuracy by avoiding confounding signals that have plagued earlier methods, particularly the misclassification of clonal hematopoiesis mutations as tumor-derived[3].

This diagnostic uncertainty presents a practical dilemma: should clinicians proceed with empiric immunotherapy or chemotherapy based on a negative LBx, or delay treatment for confirmatory tissue testing, risking disease progression? By stratifying negative results, ctDNA TF provides a rational framework to guide treatment decisions while minimizing the risk of misinterpretation.

THE CTDNA TF AS A BIOMARKER

Study findings

The results presented in Table 1 illustrate the central finding of Rolfo et al.[11]: the interpretation of negative LBx results depends critically on the amount of ctDNA in plasma, as measured by the ctDNA TF. When results are interpreted without stratification, the concordance between LBx and TBx is modest, with a positive percent agreement (PPA) of 63% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 66%. These metrics highlight the inherent limitations of LBx when considered in isolation, and they help explain why regulatory agencies currently recommend reflex tissue testing in the case of negative findings.

Clinical implications of ctDNA tumor fraction-guided interpretation of negative liquid biopsy results, adapted from Rolfo et al.[11]

| Aspect | Clinical implications |

| Overall concordance LBx vs. TBx | Negative LBx results are unreliable without further context |

| High ctDNA tumor fraction (TF ≥ 1%) | Negative LBx with high TF may be considered informative negatives, allowing timely treatment initiation |

| Low ctDNA tumor fraction (TF < 1%) | Negative LBx with low TF are indeterminate and require confirmatory tissue biopsy |

| NSCLC reflex testing cohort | Reflex TBx uncovers missed actionable drivers, enabling targeted therapy |

| Treatment timing | Reflex TBx may delay treatment, but it is critical in low-TF cases |

| Targeted therapy use | Timely TBx increases access to targeted therapies and improves outcomes |

| Survival outcomes | Confirmatory testing in low-TF patients improves survival through appropriate therapy selection |

Introducing ctDNA TF as a stratification biomarker could fundamentally shift this paradigm. In samples with high TF (≥ 1%), the sensitivity and reliability of LBx improve dramatically, with PPA and NPV reaching 98% and 97%, respectively. In these cases, negative LBx results can be regarded as “informative negatives”, allowing clinicians to exclude actionable driver mutations and initiate therapy without waiting for tissue confirmation. This has immediate clinical significance, as it accelerates treatment initiation, particularly in patients with advanced NSCLC, where delays are associated with poorer survival outcomes[12].

Conversely, low-TF samples present a higher clinical risk. When TF is < 1%, the probability of false-negative results increases substantially. Among NSCLC patients in this subgroup, more than half of the negative LBx cases were subsequently found to harbor actionable mutations upon reflex TBx. These findings underscore the necessity of tissue confirmation in low-TF contexts, as failure to do so could result in missed targetable alterations, such as EGFR, Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2), ERBB2 or ALK, all of which have established targeted therapies that improve survival[13].

Data from the reflex testing cohort further illustrate the consequences of relying only on LBx. Among 505 patients with negative LBx who underwent TBx, 37% were found to carry actionable driver mutations, most commonly KRAS, EGFR, ERBB2 and ALK. Without reflex TBx, nearly four out of ten patients in the low-TF subgroup could have been denied access to potentially life-saving targeted therapies. Although reflex TBx delayed treatment initiation (median 4.7 weeks vs. 1.8 weeks for immediate therapy), it significantly increased the likelihood of receiving a matched targeted therapy (17% vs. 4%) and translated into meaningful survival benefits, with a real-world progression-free survival (rwPFS) of 15.9 months and overall survival (rwOS) of 45.8 months among patients who ultimately received therapy guided by tissue-based molecular profiling[11].

Clinical relevance

Taken together, these results support a two-tiered clinical strategy for interpreting negative LBx results. High-TF negative results can be trusted and should prompt timely initiation of systemic therapy, avoiding unnecessary invasive procedures. By contrast, low-TF negative results remain indeterminate and require tissue confirmation to ensure no actionable mutations are missed. This stratified approach exemplifies precision oncology, aligning not only therapy with molecular alterations but also diagnostic intensity with the likelihood of obtaining clinically relevant information[14].

The implications of this framework extend beyond NSCLC. In colorectal cancer, accurate exclusion of Rat sarcoma protein (RAS) and BRAF mutations is critical for guiding anti-EGFR therapy[15]. Similarly, in breast and prostate cancers, where emerging biomarkers increasingly influence treatment decisions, high-TF negatives may suffice to guide therapy, whereas low-TF negatives necessitate further investigation[16].

Importantly, the clinical interpretation of TF- stratified negative results may need to be contextualized according to the class of genomic alteration being assessed. As highlighted by Rolfo et al.[11], current evidence for TF-based interpretation is strongest for short variants and rearrangements, which were the focus of their analysis. For other classes of genomic alterations, such as copy-number alterations or high-level amplifications, detection is generally more dependent on tumor DNA fraction, suggesting that TF thresholds may need to be interpreted in an alteration-specific manner in clinical practice.

The clinical significance of these findings is considerable. For patients with high ctDNA TF and negative results, clinicians could be confident that the absence of detectable alterations reflects the tumor’s genomic profile, enabling timely initiation of immunotherapy or chemo-immunotherapy[3]. Accelerating time to treatment is particularly critical in NSCLC, where even short delays can reduce the likelihood of patients receiving targeted therapy[16]. Conversely, patients with low TF require a different clinical pathway, since negative results in this context cannot be taken at face value, and reflex to TBx becomes essential. Rolfo et al.[11] demonstrated that more than one-third of patients in the low-TF subgroup benefited from tissue-based detection of actionable mutations, and timely confirmatory testing significantly increased the uptake of targeted therapies, leading to longer progression-free and overall survival.

An additional consideration is that ctDNA TF is not a static parameter and may change over time in response to treatment or disease evolution. In patients with initially high TF, a subsequent decline following systemic therapy may reflect biological response rather than technical failure of LBx[17]. In this context, a negative LBx result should be interpreted cautiously, taking into account prior TF levels and treatment history. Rather than representing a false-negative result, declining TF may indicate effective tumor suppression, whereas re-emergence or increase in TF on serial testing may signal molecular progression before radiographic evidence[18]. Although prospective data are still limited, emerging real-world experience suggests that longitudinal assessment of TF may add clinical value by contextualizing serial negative results and informing decisions on surveillance, treatment continuation, or the need for repeat TBx. Importantly, this dynamic interpretation reinforces the role of TF as a contextual biomarker, complementing other clinical and radiologic parameters.

Beyond patient outcomes, ctDNA TF also has important implications for healthcare systems. TBx is invasive, costly, and often associated with complications such as pneumothorax or bleeding, in addition to patient anxiety and discomfort[19]. Identifying patients who truly require tissue confirmation could reduce unnecessary procedures, optimize resource allocation, and lower costs. For patients with high TF, reflex biopsy may be avoided, whereas for those with low TF, prioritizing tissue confirmation ensures that no opportunities for targeted therapy are missed[11].

The strengths of the study by Rolfo et al.[11] reinforce the credibility of these conclusions. The analysis included over 3,800 paired samples from multiple tumor types, validated in a nationwide clinicogenomic database, providing robust statistical power and reflecting real-world practice. The TF estimation methodology was innovative, incorporating aneuploidy patterns, variant allele frequencies and multiomic signatures, while systematically excluding germline and clonal hematopoiesis confounders[11].

These strengths also point toward broader implications for precision oncology. With prospective validation, ctDNA TF could be integrated into diagnostic algorithms and even clinical guidelines such as those from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) or European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO). Workflows might be structured so that patients with a positive LBx receive immediate targeted therapy, patients with negative LBx and high TF proceed with immunotherapy, and patients with a negative LBx and low TF undergo reflex to TBx. Such algorithms could streamline clinical practice, reduce variability among clinicians, and standardize care pathways across institutions. Moreover, by reducing unnecessary biopsies, TF-guided interpretation has the potential to lower costs and improve patient experience, aligning precision oncology with both clinical and economic priorities.

Limitations of the study

While ctDNA TF represents a promising interpretive biomarker, several limitations must be considered when translating it into clinical practice. First, the retrospective nature of the data collection introduces potential biases that may not fully capture the complexity of patient selection, sample handling and sequencing conditions in real-world settings. Without prospective validation, the generalizability of these findings remains constrained. Another important limitation concerns the molecular scope of the analysis. The reliability of ctDNA TF has been primarily demonstrated for short variants and rearrangements, which are the most common targetable alterations in cancers such as NSCLC and colorectal cancer. However, copy-number alterations, which often require a higher tumor DNA fraction for accurate detection[20], may not be as reliably assessed using the current approach. This restricts the applicability of the conclusions to a subset of genomic alterations and suggests that further refinement is needed before TF can be applied across all variant types.

In addition, the methodology for TF estimation is proprietary to Foundation Medicine and optimized for their comprehensive genomic profiling platform. It remains unclear whether comparable accuracy and predictive value can be achieved with other commercial assays or laboratory-developed tests. This platform dependence raises questions regarding reproducibility, standardization and cross-laboratory validation.

Beyond these study-specific limitations, important research blind spots remain, including the lack of standardized ctDNA TF thresholds across assays and tumor types, limited prospective validation of TF-guided clinical algorithms, and uncertainty regarding the interpretation of low TF in specific clinical contexts, such as indolent disease or low-volume metastatic burden. Addressing these research blind spots will be essential for broader clinical adoption of TF-stratified LBx interpretation.

Despite these limitations, ctDNA TF offers a relatively simple and quantitative biomarker that could fundamentally improve the interpretation of negative LBx results. In a field where rapid action is crucial and false reassurance can be harmful, ctDNA TF provides the contextual information that clinicians have long needed.

CONCLUSION

Rolfo et al.[11] present a compelling case for ctDNA TF as a transformative biomarker in the interpretation of LBx results. Their findings demonstrate that not all negative results are equivalent; high-TF negatives can be trusted, while low-TF negatives demand caution and reflex testing. This framework has the potential to accelerate treatment initiation, reduce invasive procedures and optimize the use of targeted therapy. Nonetheless, widespread adoption will depend on prospective validation, harmonization across platforms, and careful integration into clinical guidelines.

Furthermore, ctDNA TF underscores a central principle in precision oncology: molecular data must be interpreted within the context of biological and clinical frameworks. As LBx technologies continue to advance, biomarkers such as TF will be critical in bridging the gap between the analytical potential of LBx and clinical confidence.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Wrote and revised the original manuscript, and designed the graphical abstract: Cardoso GC

Conceptualized and revised the manuscript: Amancio de Souza Ramos E

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

The first author is supported by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), Brazil, through a fellowship linked to the National Institute of Science and Technology - CERBC (INCT-CERBC grant no. 406645/2022-1).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Caputo V, De Falco V, Ventriglia A, et al. Comprehensive genome profiling by next generation sequencing of circulating tumor DNA in solid tumors: a single academic institution experience. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2022;14:17588359221096878.

2. Ignatiadis M, Sledge GW, Jeffrey SS. Liquid biopsy enters the clinic - implementation issues and future challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:297-312.

3. Husain H, Pavlick DC, Fendler BJ, et al. Tumor fraction correlates with detection of actionable variants across > 23,000 circulating tumor DNA samples. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2200261.

4. Basharat S, Farah K. An overview of comprehensive genomic profiling technologies to inform cancer care. Can J Health Technol. 2022;2:1-19.

5. Liu SC. Circulating tumor DNA in liquid biopsy: current diagnostic limitation. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:2175-8.

6. Nigro MC, Marchese PV, Deiana C, et al. Clinical utility and application of liquid biopsy genotyping in lung cancer: a comprehensive review. Lung Cancer. 2023;14:11-25.

7. Woodhouse R, Li M, Hughes J, et al. Clinical and analytical validation of FoundationOne Liquid CDx, a novel 324-Gene cfDNA-based comprehensive genomic profiling assay for cancers of solid tumor origin. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0237802.

8. van der Leest P, Rozendal P, Rifaela N, et al. Detection of actionable mutations in circulating tumor DNA for non-small cell lung cancer patients. Commun Med. 2025;5:204.

9. Treichler G, Hoeller S, Rueschoff JH, et al. Improving the turnaround time of molecular profiling for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: outcome of a new algorithm integrating multiple approaches. Pathol Res Pract. 2023;248:154660.

10. Raez LE, Brice K, Dumais K, et al. Liquid biopsy versus tissue biopsy to determine front line therapy in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Clin Lung Cancer. 2023;24:120-9.

11. Rolfo CD, Madison RW, Pasquina LW, et al. Measurement of ctDNA tumor fraction identifies informative negative liquid biopsy results and informs value of tissue confirmation. Clin Cancer Res. 2024;30:2452-60.

12. Romine PE, Sun Q, Fedorenko C, et al. Impact of diagnostic delays on lung cancer survival outcomes: a population study of the US SEER-medicare database. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:e877-85.

13. Gálffy G, Morócz É, Korompay R, et al. Targeted therapeutic options in early and metastatic NSCLC-overview. Pathol Oncol Res. 2024;30:1611715.

14. Edsjö A, Holmquist L, Geoerger B, et al. Precision cancer medicine: concepts, current practice, and future developments. J Intern Med. 2023;294:455-81.

15. Gong J, Cho M, Fakih M. RAS and BRAF in metastatic colorectal cancer management. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:687-704.

16. Bartolomucci A, Nobrega M, Ferrier T, et al. Circulating tumor DNA to monitor treatment response in solid tumors and advance precision oncology. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2025;9:84.

17. Al-Showbaki L, Wilson B, Tamimi F, et al. Changes in circulating tumor DNA and outcomes in solid tumors treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11:e005854.

18. Gouda MA, Huang HJ, Piha-Paul SA, et al. Longitudinal monitoring of circulating tumor DNA to predict treatment outcomes in advanced cancers. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2100512.

19. Ma L, Guo H, Zhao Y, et al. Liquid biopsy in cancer current: status, challenges and future prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:336.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].