Electrochemically active materials as critical components for next-generation solid-state electrolytes

Abstract

In the traditional view, low reactivity, low electronic conductivity, and high ionic conductivity are necessary for designing advanced solid-state electrolytes. However, this concept limits the range of materials selection and the optimization direction. Recent studies have shown the great potential of electrochemically active materials with mixed conductivity in solid-state electrolytes, exhibiting great ion transport capacity and interface performance. Therefore, it is urgent to re-examine the roles of reactivity and relationships between ionic and electronic conductivity in electrolytes. This perspective aims to clarify the ion-electron transport behavior and decoupling strategies of mixed conductive materials, discuss their contributions to ion transport and interface optimization in solid-state electrolytes, and finally propose innovative directions for designing next-generation solid-state lithium metal batteries.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Solid-state lithium metal batteries (SSLMBs) have great potential to achieve low-cost, high-energy-density, long-life and high-safety power/energy storage systems[1,2]. However, there are bottlenecks at solid-state electrolytes (SSEs) and electrode-electrolyte interfaces[3,4]. The advanced inorganic solid-state electrolytes (ISEs, such as oxides, sulfides, halides, etc.)[5] have comparable ionic conductivity to liquid electrolytes. But the stable interface performance needs additional processing (high external pressure, electrode-electrolyte integration, co-sintering, interface/interphase layer, etc.)[6-8]. Polymer solid-state electrolytes (PSEs) have advantages in interface contact[9]. However, most modifications rely on environmentally unfriendly fluorine element[10]. Although many fluorine-free electrolytes have been explored, the comprehensive performance is unsatisfactory[11].

To achieve industrialization of SSEs, it is urgent to break through conventional systems and design principles (low electronic conductivity, low reactivity, etc.). Electrode materials, called electrochemically active materials (EAMs), have been excluded for their mixed ion-electron conductivity and electrochemical activity (oxidation/reduction reaction with lithium-ions at specific potential)[12]. The coexistence of electronic conductivity and electrochemical activity of SSEs is recognized to cause rapid failure in SSLMBs. However, recently reported EAM-based SSEs greatly challenge this concept[13-15].

To reconcile this contradiction, it is necessary to re-examine EAMs. This perspective focuses on the following critical issues: how to understand and decouple ion-electron transport of EAMs? How do ions conduct in polymer-in-EAM systems without causing a short circuit? How do electrode-electrolyte interfaces of EAMs stabilize? This perspective aims to provide insights for utilizing low-cost EAMs as next-generation SSEs and accelerate the application of SSLMBs.

ION-ELECTRON TRANSPORT PROPERTIES AND DECOUPLING STRATEGIES OF ELECTROCHEMICALLY ACTIVE MATERIALS

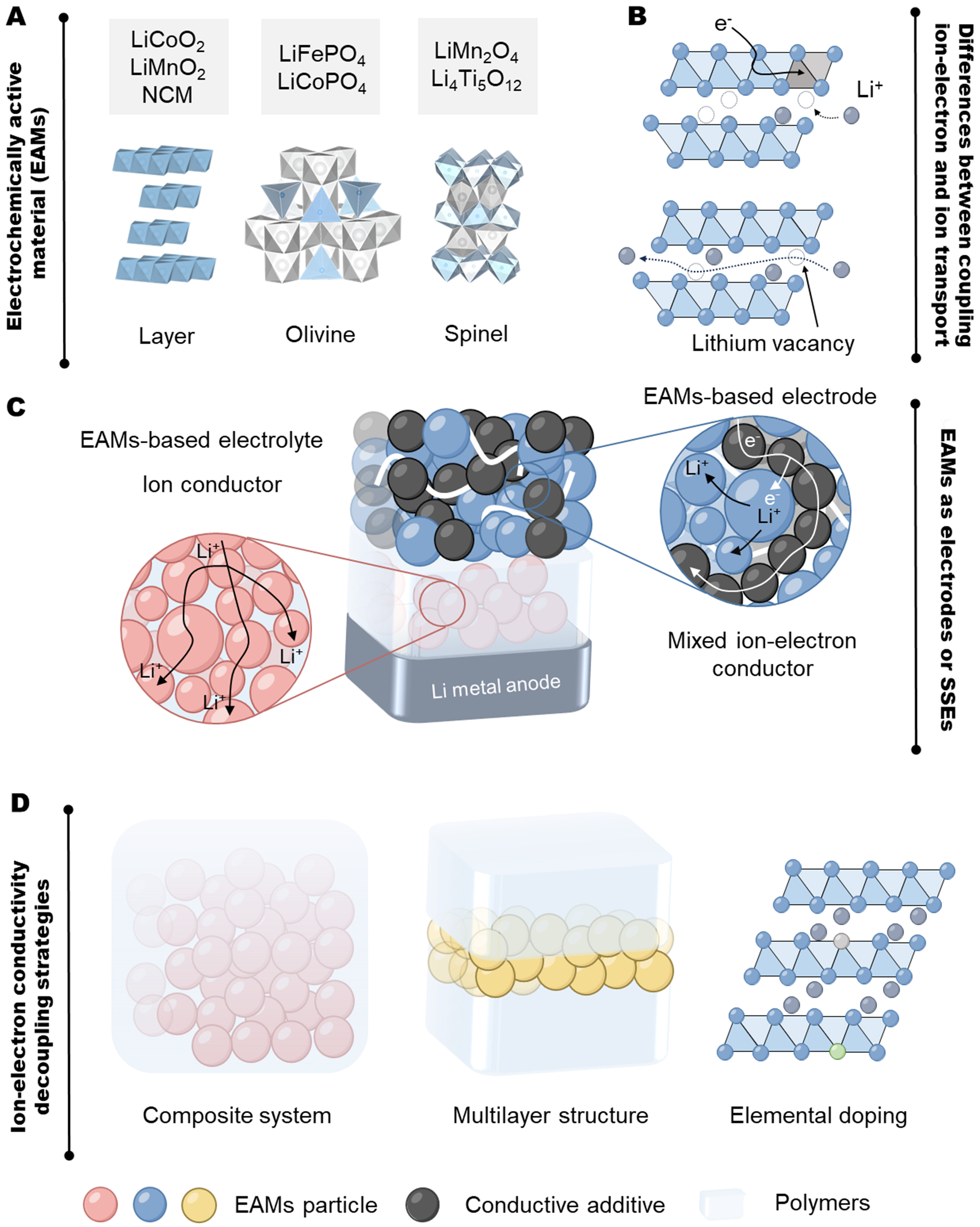

EAMs are commonly categorized into layered (LiCoO2, LiMnO2, LiNi1-x-yCoxMnyO2, etc.), olivine [LiFePO4 (LFP), LiCoPO4, etc.] and spinel type [LiMn2O4, Li4Ti5O12 (LTO), etc.] [Figure 1A][16]. Layered EAMs rely on interlayer diffusion through two-dimensional channels, whereas olivine and spinel rely on polyhedral vacancies for multidimensional vacancy/gap diffusion[17]. As electrodes, this intercalation reaction is inevitably accompanied by electronic gain/loss at oxidation/reduction sites and phase transition/solid solution reactions. The Bulter-Volmer equation is commonly used to describe the electrochemical reaction kinetics of electrodes, ignoring the complexity of coupled ion-electron transfer (CIET). Recently reported CIET models indicate the synergistic effect of electron transfer (ET) and ion transfer (IT) on the CIET transition state. Based on relevant parameters (Fermi distribution, electron transmission frequency, reaction free-energy barrier, exposed available site concentrations, lithium vacancy fraction, etc.), the excess chemical potential between oxidized and reduced states of lithium ions and their atomic environment can be changed, thereby limiting electrochemical reactions and exhibiting ion conductivity[18-20]. Additionally, pure ionic conductors have a lower requirement for lithium vacancies compared to electrodes with reversible storage [Figure 1B].

Figure 1. Basic introduction of EAMs. (A) Various crystal configurations of common EAMs; (B) Differences between coupling ion-electron and ion transport; (C) Differences in ion-electron transport behavior of EAMs when used as electrodes and electrolytes; (D) Feasible strategies for decoupling ion and electron conductivity in EAMs. EAMs: Electrochemically active materials; NCM: lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide.

Although commercial electrodes have demonstrated sufficient ion conductivity, their electronic conductivity is overestimated due to conductive coatings. In fact, some EAMs have satisfied the low electronic conductivity requirement for electrolytes (< 10-8 S·cm-1)[21]. Even if higher than this value, as long as their ionic conductivity is at least three orders of magnitude greater than the electronic conductivity, they mainly function as ionic conductors [Figure 1C].

In addition, the electron conductivity of EAMs can affect the interfacial potential and electric double layer (EDL)[22]. The internal potential of SSEs presents a gradient distribution, accompanied by the potential drop at the interface. To avoid electrochemical reactions, it is essential to suppress the reactivity or ensure that the reaction window does not overlap with the actual potential.

To mitigate the electronic conductivity and reactivity, this perspective proposes some strategies for decoupling ion-electron transport [Figure 1D]:

(1) Composite system. The transmission frequency of electrons and the concentration of exposed available sites can influence the rate constant of CIET. Insulating polymers can reduce the contact with electrons and sites. Li0.95Na0.05FePO4 (LNFP) with 50 wt.% polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) has low electronic conductivity (< 10-9 S·cm-1), avoiding the redox behavior and widening the electrochemical stability window (ESW) to

(2) Multilayer structure. This method directly avoids CIET. The insulating interlayers directly cut off the electronic pathway, and the EAM layer exhibits superior mechanical strength. For example, applying interlayers to LiMn2O4 membranes can reduce the electronic conductivity from 10-6 to 10-10 S·cm-1[14]. Similarly, polymer interlayers suppress electrochemical activity of Li3VO8, LTO and LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2[24].

(3) Element doping. EAMs as SSEs require high ionic conductivity and low electronic conductivity, rather than mixed conductivity as electrodes. The topology and defect structure of crystals determine this behavior. Doping elements that widen diffusion channels and create lithium vacancies can enhance lithium-ion migration. Electronic conductivity can be suppressed by introducing defects that capture charge carriers. For example, Na-doped LNFP can maintain the original topology and exhibit higher ion conductivity[15]. Additionally, introducing elements with stable valence states (Mg2+, Al3+, etc.) can suppress the formation of mixed valence states (Fe3+/Fe2+, Ti4+/Ti3+, etc.) and reduce electronic conductivity[25].

ION CONDUCTION BEHAVIOR OF ELECTROCHEMICALLY ACTIVE MATERIALS IN COMPOSITE SYSTEMS

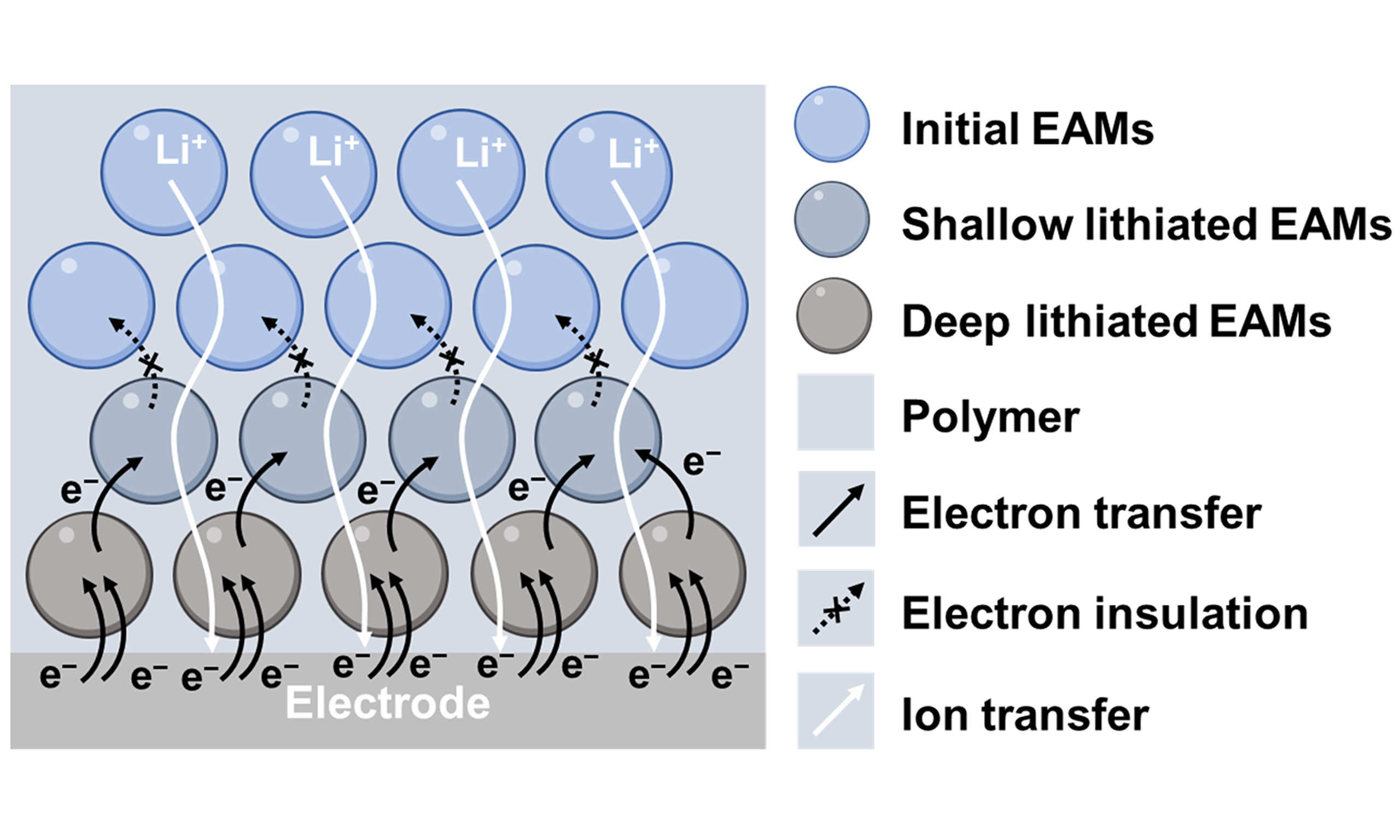

Conventional understanding suggests that the content of mixed ion-electron conductors in composite systems must be kept within the percolation threshold (10-50 wt.%) to avoid forming electronic pathways. However, the proportion of EAMs can reach 50-80 wt.%. In these systems, EAMs dominate the ion conduction. Polymers can form insulating layers around EAMs. Although the single layer may not satisfy the minimum thickness for electron shutdown, multilayers can progressively reduce this possibility, blocking long-distance electron transmission [Figure 2A].

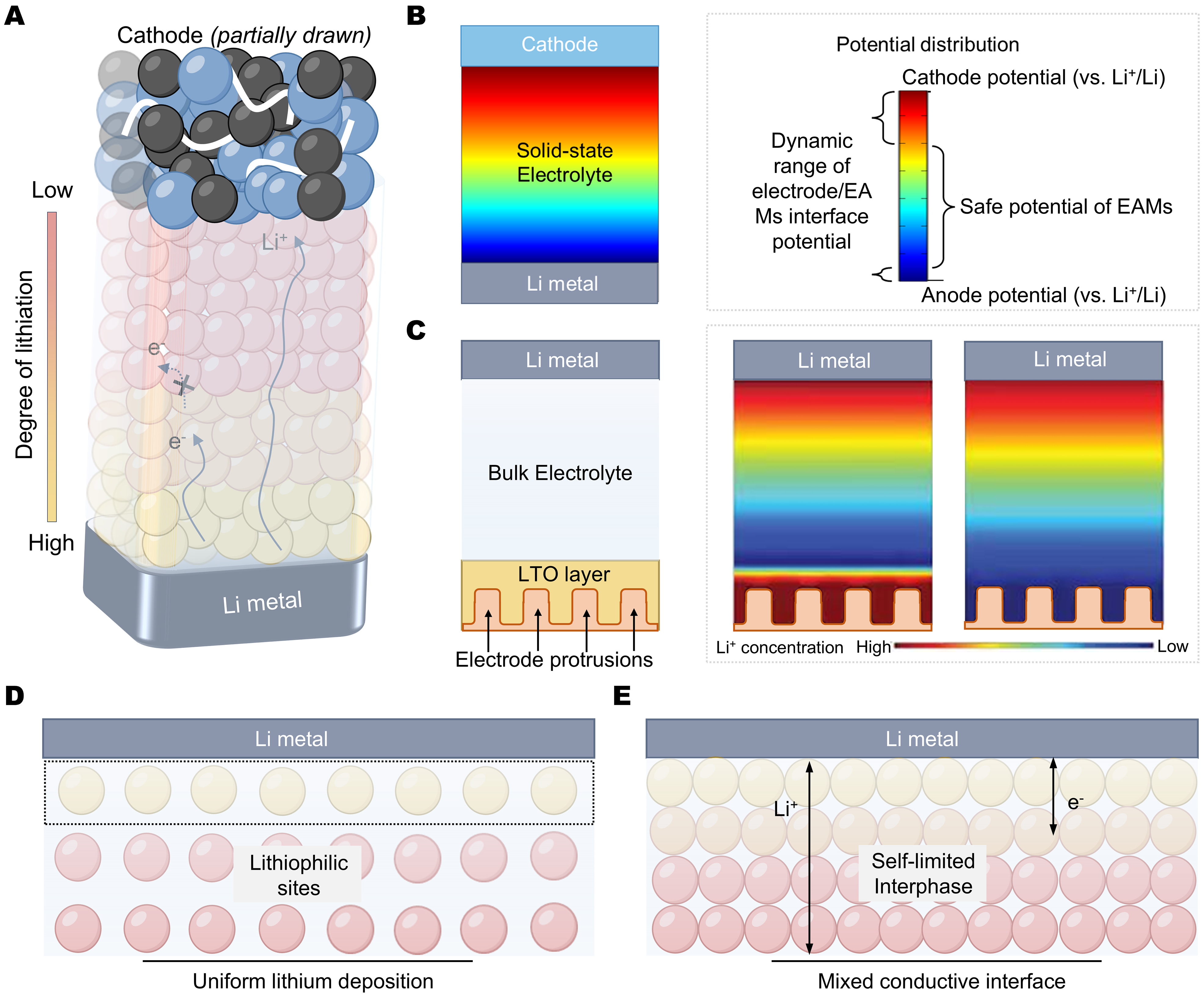

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of EAM-based SSEs. (A) Ion-electron transport behavior. In case the single insulating polymer layer may leak some electrons, the continuous multilayers ensure the complete insulation of whole SSEs; (B) Insulation design of EAM-based SSEs in the condition of dynamic potential distribution. The interface superiorities: (C) Ion concentration redistributor; (D) Lithiophilic sites; (E) Mixed conductive interface. EAM: Electrochemically active material; EAMs: electrochemically active materials; SSEs: solid-state electrolytes; LTO: Li4Ti5O12.

Additionally, the contribution of polymers to ion transport is low, even at reduced crystallinity. However, at the polymer-EAM interface, the applied electric field induces polarization of the EAMs, causing electrons and holes to migrate in opposite directions[26,27]. This property accelerates the dissociation of lithium salts and the transport of lithium ions at the interface. Certain EAMs also exhibit high adsorption energy for lithium ions, further improving the interfacial carrier concentration.

INTERFACE REACTION MECHANISM AND ADVANTAGES BETWEEN ELECTROCHEMICALLY ACTIVE MATERIALS AND ELECTRODES

The electronic conductivity of EAMs can be effectively suppressed by decoupling strategies. However, the actual surface potential of SSEs varies at the electrode-electrolyte interface during the formation of the EDL and the charging/discharging processes[28-30]. To prevent electrochemical reactions, the reaction potential should be separated from the dynamic surface potential at the cathode or anode, or it must be insulated within SSEs at the reaction potential, which imposes strict requirements on insulation design [Figure 2B].

Some EAMs also show reactivity with lithium metal. The electrochemical reaction potential of LTO

Nevertheless, in composite systems, polymers impede ET, and the lithiation kinetics deteriorate within the interior of SSEs. The lithiation also decreases reactive lithium vacancies and the surficial potential, achieving dynamic equilibrium with lithium metal. This self-limiting reaction offers many advantages in regulating the electrode-electrolyte interface [Figure 2C-E]:

(1) Ion concentration redistribution. EAMs can form a gradient lithiation layer on the lithium metal surface, with a higher lithiation degree near the electrode that decreases toward the interior. This gradient layer increases the lithium-ion concentration at the electrode surface, preventing ion depletion.

(2) Lithiophilic sites. EAMs typically exhibit a high adsorption energy with lithium ions. This affinity can reduce the energy barriers of lithium nucleation and deposition, inducing uniform lithium deposition.

(3) Mixed conductive interface. Most lithiated EAMs have high electronic conductivity, enabling the formation of a mixed conductive interface. This field can alleviate the polarization and eliminate lithium dendrites through reaction[13,24].

APPLICATION PROSPECTS AND CHALLENGES OF ELECTROCHEMICALLY ACTIVE MATERIALS IN SOLID-STATE ELECTROLYTES

Widely studied ISEs face challenges in mass production. Sulfides exhibit high ionic conductivity and good ductility, but have poor air stability, high cost due to critical raw materials such as Li2S, and require high operating pressure. Oxides are air-stable but have poor interfacial contact and are prone to dendrite formation at crystal boundaries or voids. Halides offer controllable costs, though their chemical stability requires further optimization. In comparison, mass-produced EAMs (LFP, LTO, etc.) have significant advantages in terms of preparation and cost. Low-pressure operation of electrodes shows promise for addressing interfacial challenges in ISEs. In addition, electrolyte membranes of air-stable EAMs can be directly fabricated using existing battery production lines, enabling roll-to-roll assembly.

Even with some successful cases [Supplementary Table 1], EAM-based SSEs face many challenges:

(1) Ion conduction. The ionic conductivity of EAMs (10-6-10-4 S·cm-1) lags behind that of advanced SSEs (10-3-10-2 S·cm-1). Through structural optimization and design - such as element doping, surface coating, morphology control, and ultra-thin SSEs - ion transport can be enhanced.

(2) Electrode-electrolyte interface. Although EAM-based SSEs exhibit superior interfaces compared to other ISEs, the impact of polymers on reactivity and ion conductivity must be balanced. Using ion-conductive polymers instead of conventional binders is a promising approach.

(3) Decoupling method of ion-electron conduction. Surface coating is also promising for suppressing electronic conductivity. However, all strategies require support from more advanced theories and detection methods to observe dynamic potential distribution in situ and quantify interfacial reactions.

In summary, EAM-based SSEs offer advantages in low cost and industrial compatibility. The primary priorities are to enhance ionic conductivity and balance surface electronic conductivity and reactivity. With appropriate modifications, they are expected to become critical components of next-generation SSLMBs.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization and manuscript design: Xu, Y.; Wu, Y.

Figure preparation: Xu, Y.; Peng, Y.

Manuscript writing: Xu, Y.

Manuscript discussion: Xu, Y.; Xiong, X.; Zhou, Q.; Peng, B.; Eliseeva, S.

Manuscript editing and polishing: Wu, Y.; Holze, R.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, T.

All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52073143, 22279016), Key Project (No. 52131306), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFB2400400), the Project on Carbon Emission Peak and Neutrality of Jiangsu Province (No. BE2022031-4), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Nos. BK20200696, BK20200768, 20KJB430019), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Nos. 2242023R10001, 2242024K30047), the Start-up Research Fund of Southeast University (No. RF1028623005), and the Zhishan Young Scholar Program of Southeast University (No. 2242024RCB0004).

Conflicts of interest

Wu, Y. serves as Editor-in-Chief of Energy Z. He was not involved in any aspect of the editorial process for this manuscript, including the selection of reviewers, handling of the manuscript, or the final editorial decision. All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Huang, X. Y.; Zhao, C. Z.; Kong, W. J.; et al. Tailoring polymer electrolyte solvation for 600 Wh kg-1 lithium batteries. Nature 2025, 646, 343-50.

2. Fu, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; et al. A cost-effective all-in-one halide material for all-solid-state batteries. Nature 2025, 643, 111-8.

3. Xu, R.; Xu, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. Potential-gated polymer integrates reversible ion transport and storage for solid-state batteries. Adv. Mater. 2025, e13365.

4. Zhang, S.; Zhao, F.; Li, L.; Sun, X. Solid-state electrolytes expediting interface-compatible dual-conductive cathodes for all-solid-state batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 6530-9.

5. Chen, Y.; Qian, J.; Wang, K.; Li, L.; Wu, F.; Chen, R. Cutting-edge developments at the interface of inorganic solid-state electrolytes. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2502653.

6. Pei, F.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Interfacial self-healing polymer electrolytes for long-cycle solid-state lithium-sulfur batteries. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 351.

7. Dai, P.; Liao, J.; Li, J.; et al. Structural instability of NCM-LATP composite cathode during co-sintering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2421775.

8. Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Dong, C.; et al. Fluorinated coating stabilizing halide solid electrolytes for all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2025, 75, 104107.

9. Sand, S. C.; Rupp, J. L. M.; Yildiz, B. A critical review on Li-ion transport, chemistry and structure of ceramic-polymer composite electrolytes for solid state batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 178-200.

10. Zhu, J.; Bian, P.; Sun, G.; et al. Practical high-voltage lithium metal batteries enabled by the in-situ fabrication of main-chain fluorinated polymer electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2025, 64, e202424685.

11. Xu, W.; Zhou, L.; Lu, S.; He, J.; Xu, Y.; Tian, L. Fluorine-free gel polymer electrolyte for lithium oxide-rich solid electrolyte interphase and stable Li metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9308.

12. Xiong, X.; Jiang, G.; Li, H.; Chen, L.; Suo, L. All-electrochem-active all solid state batteries. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2025, 79, 104330.

13. Zhou, Q.; Yang, X.; Xiong, X.; et al. A solid electrolyte based on electrochemical active Li4Ti5O12 with PVDF for solid state lithium metal battery. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2201991.

14. Du, J.; Chen, Z.; Peng, B.; et al. A solid-state electrolyte based on electrochemically active LiMn2O4 for lithium metal batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2024, 12, 33241-8.

15. Peng, B.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; et al. A solid-state electrolyte based on Li0.95Na0.05FePO4 for lithium metal batteries. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2307142.

16. Xu, C.; Peng, B.; Yang, W.; Tian, J.; Zhou, H. High energy density lithium battery systems: from key cathode materials to pouch cell design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 10245-303.

17. Wang, R.; Wang, L.; Liu, R.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Ran, F. “Fast-charging” anode materials for lithium-ion batteries from perspective of ion diffusion in crystal structure. ACS. Nano. 2024, 18, 2611-48.

18. Zhang, Y.; Fraggedakis, D.; Gao, T.; et al. Lithium-ion intercalation by coupled ion-electron transfer. Science 2025, 390, eadq2541.

19. Halldin Stenlid, J.; Žguns, P.; Vivona, D.; et al. Computational insights into electrolyte-dependent Li-ion charge-transfer kinetics at the LixCoO2 interface. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2024, 9, 3608-17.

20. Song, A.; Zhang, W.; Ma, L.; et al. Decoupling ion-electron transport in thick solid-state battery electrodes. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2024, 9, 5027-36.

21. Zhao, F.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; et al. Anion sublattice design enables superionic conductivity in crystalline oxyhalides. Science 2025, 390, 199-204.

22. He, Y.; Wang, L.; He, X. Material-specific electric double layers: reviewing the theory to advance understanding of battery interfaces. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2025, 82, 104554.

23. Wang, Z.; Tang, X.; Yuan, S.; et al. Engineering vanadium pentoxide cathode for the zero-strain cation storage via a scalable intercalation-polymerization approach. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2100164.

24. Zou, P.; Wang, C.; He, Y.; Xin, H. L. Broadening solid ionic conductor selection for sustainable and earth-abundant solid-state lithium metal batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 5871-80.

25. Kim, H. m.; Kim, D. w.; Hara, K.; et al. Mixed anion effects on structural and electrochemical characteristics of Li4Ti5O12 for high-rate and durable anode materials. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2024, 12, 7107-21.

26. Zong, C.; Zhu, X.; Xu, Z.; et al. Isomeric dibenzoheptazethrenes for air-stable organic field-effect transistors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 16230-6.

27. Jin, Y.; Lin, R.; Li, Y.; et al. Revealing the influence of electron migration inside polymer electrolyte on Li+ transport and interphase reconfiguration for Li metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202403661.

28. Cheng, Z.; Liu, M.; Ganapathy, S.; et al. Revealing the impact of space-charge layers on the Li-ion transport in all-solid-state batteries. Joule 2020, 4, 1311-23.

29. Kimura, Y.; Fujisaki, T.; Shimizu, T.; Nakamura, T.; Iriyama, Y.; Amezawa, K. Coating layer design principles considering lithium chemical potential distribution within solid electrolytes of solid-state batteries. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 125.

30. Yamamoto, K.; Iriyama, Y.; Asaka, T.; et al. Dynamic visualization of the electric potential in an all-solid-state rechargeable lithium battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010, 49, 4414-7.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].