Ferroptosis at a crossroads: five fundamental questions for the next decade

Abstract

Ferroptosis - a regulated form of cell death driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation - has rapidly transitioned from a biochemical curiosity to a clinically relevant mechanism with implications for cancer therapy, immune regulation, neurodegeneration, and inflammatory diseases. Despite substantial advances, key mechanistic questions remain unresolved, limiting the therapeutic exploitation of ferroptosis. In this perspective, we outline five critical challenges that require integrated efforts across biochemistry, cancer biology, immunology, and clinical research: (1) the molecular identity and mechanism of the ferroptotic pore; (2) the regulation and physiological origin of the labile iron pool; (3) the role of metabolic and organellar networks in determining ferroptosis sensitivity; (4) the development of ferroptosis-specific biomarkers for diagnosis and drug discovery; and (5) the immunological outcomes of ferroptotic cell death. Addressing these knowledge gaps is essential for establishing a mechanistic framework to guide rational drug design, patient stratification, and the safe therapeutic modulation of ferroptosis in human disease.

Keywords: ferroptosis, immunological responses, labile iron pool, lipid peroxidation, metabolic regulation, therapeutic targeting

INTRODUCTION

Since its definition in 2012 as an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death[1], ferroptosis has evolved from a pharmacological observation into a unifying framework for redox biology, metabolic vulnerability, and cell death regulation. Despite rapid advances - including new lipid peroxidation pathways, iron-handling mechanisms, and therapeutic strategies - the core molecular logic of ferroptosis remains unresolved[2]. Fundamental questions concerning its execution, iron sources, tissue-specific sensitivity, in vivo manifestation, and immunological consequences persist.

This juxtaposition of rapid discovery and conceptual uncertainty marks a transition from descriptive expansion toward a mechanistic and translational phase. As with apoptosis and necroptosis, future breakthroughs will depend not on cataloging additional regulators but on defining the foundational principles governing ferroptosis in physiological and pathological contexts - an essential step for unlocking its therapeutic potential across cancer, neurodegeneration, immunity, and inflammatory disease[3].

THE EXECUTION PROBLEM: HOW DOES FERROPTOSIS ACTUALLY KILL A CELL?

All regulated cell death pathways converge on a defined execution step that irreversibly compromises membrane integrity. Apoptosis employs caspases; necroptosis relies on mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) oligomerization, and pyroptosis is executed by gasdermin pores. Ferroptosis is unique in lacking a clearly defined executor. Although iron-dependent lipid peroxidation is the initiating trigger, how oxidative lipid damage culminates in terminal membrane failure remains unresolved, complicating its distinction from uncontrolled oxidative necrosis.

Current models propose that peroxidized phospholipids - particularly oxidized polyunsaturated phosphatidylethanolamines (PUFA-PE-OOH) - destabilize membranes by altering lipid packing, curvature, and elasticity, thereby promoting bilayer weakening or transient pore formation. These effects may be counteracted by lipid detoxification and membrane repair mechanisms, including phospholipases such as phospholipase A2 group VI (PLA2G6/iPLA2β)-mediated hydrolysis of oxidized phospholipids, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member B1 (ALDH1B1)-dependent detoxification of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), and endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-III-mediated membrane repair[Figure 1].

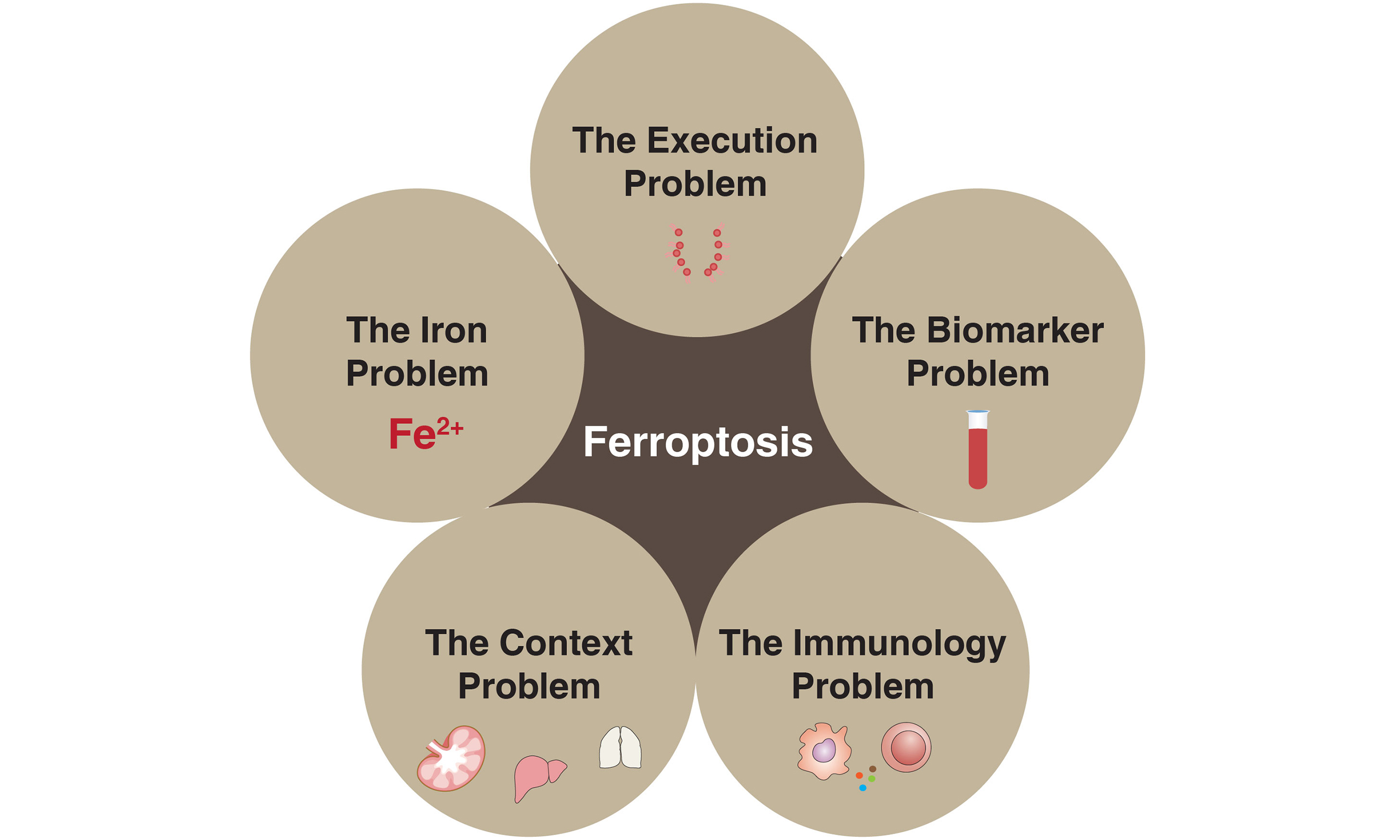

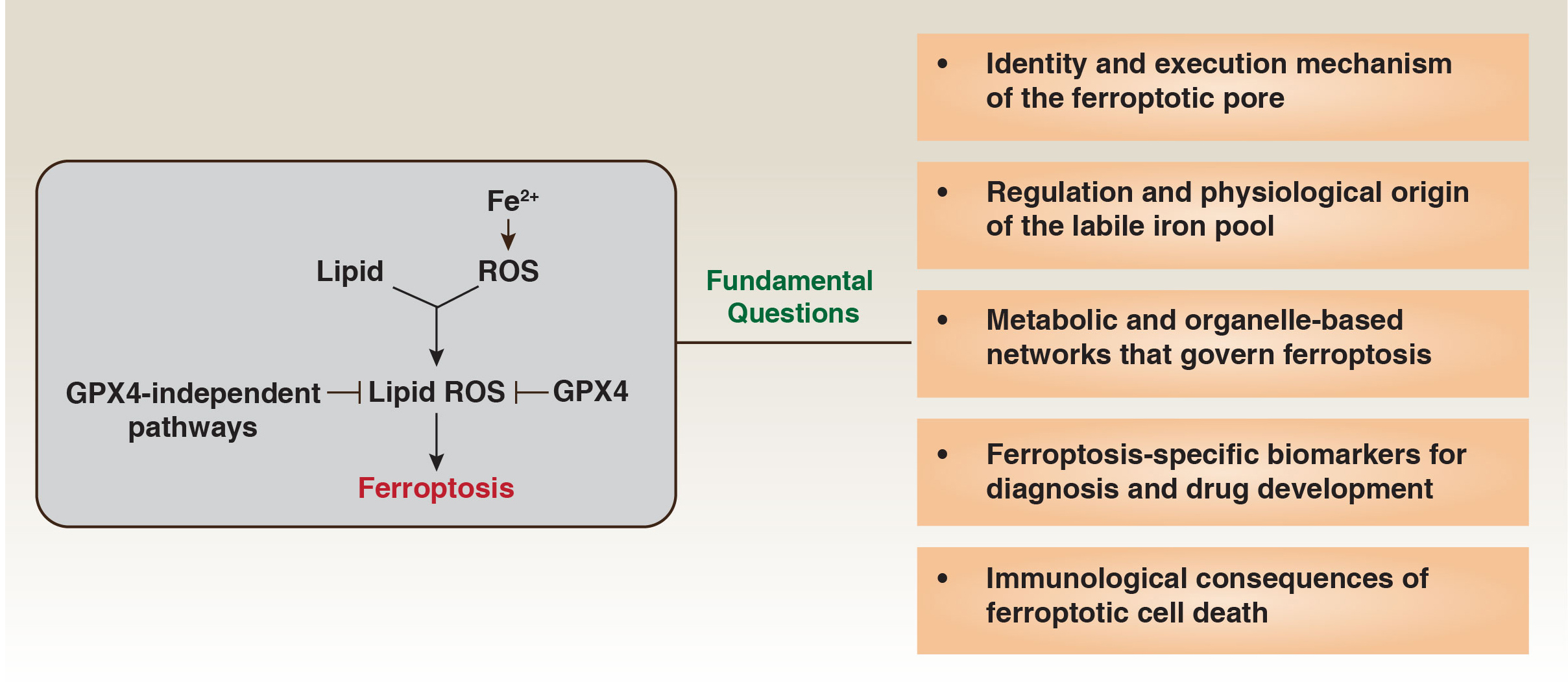

Figure 1. Fundamental questions at the core of ferroptosis biology.

Ferroptosis is driven by the accumulation of lipid-derived reactive oxygen species (lipid ROS), generated through iron-dependent oxidation of polyunsaturated lipids. Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and multiple GPX4-independent protective systems restrict lipid ROS formation, thereby preventing ferroptotic death. Despite major conceptual advances, several fundamental questions remain unresolved. These include: (1) the identity and execution mechanism of the ferroptotic pore; (2) the regulation, compartmental origin, and dynamics of the labile iron pool; (3) the metabolic and organelle-based networks that govern ferroptotic susceptibility; (4) the discovery of ferroptosis-specific biomarkers for diagnosis and therapeutic targeting; and (5) the immunological consequences of ferroptotic cell death in physiological and disease contexts.

An alternative possibility is that ferroptosis involves a dedicated protein effector. Membrane regulators such as ninjurin 1 (NINJ1)[4] and Piezo type mechanosensitive ion channel component 1 (PIEZO1)[5] have been implicated in ferroptotic membrane rupture, but definitive evidence for a protein-based executor is lacking. Resolving whether ferroptosis is executed by lipid-driven biophysical collapse, a protein-mediated mechanism, or context-dependent combinations of both remains a central challenge. Such mechanistic clarity will be essential for defining ferroptosis-specific biomarkers and designing targeted therapeutic strategies.

THE IRON PROBLEM: THE SOURCE, SPECIATION, AND MOVEMENT OF THE LETHAL IRON POOL

Iron lies at the core of ferroptosis, yet the origin and intracellular trafficking of the lethal redox-active Fe2+ pool remain incompletely defined. Cellular iron is dynamically partitioned among heme, iron-sulfur clusters, ferritin, lysosomes, and mitochondria, each with distinct redox properties and spatial constraints, complicating identification of the catalytically relevant species during ferroptosis.

Although nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4)-mediated ferritinophagy was initially viewed as the dominant source of labile iron, it is now clear that ferroptotic iron mobilization is multisourced. Lysosomes can release redox-active iron during excessive autophagy or membrane destabilization, while mitochondria contribute Fe2+ through stress-induced heme degradation and Fe–S cluster collapse. Iron uptake pathways - including transferrin receptor (TFRC)-dependent endocytosis, lactotransferrin (LTF)- and solute carrier family 39 member 14 (SLC39A14)-mediated transport, and transferrin (TF)-independent routes such as CD44 - further shape intracellular iron burden in a tissue- and microenvironment-dependent manner. Loss of iron chaperones (poly(rC)-binding protein 1 [PCBP1] and PCBP2) or exporters [lipocalin-2 (LCN2) and solute carrier family 40 member 1 (SLC40A1)] promotes iron accumulation and ferroptosis sensitivity, with context-dependent effects particularly evident for LCN2[6].

Progress in this area is limited by the lack of organelle-resolved, Fe2+-selective sensors that remain reliable under oxidative conditions, leaving most models of ferroptotic iron flux inferential rather than directly visualized. This uncertainty has clear therapeutic implications: mitochondrial iron dominance would favor mitochondria-targeted chelators or Fe–S stabilizers, whereas lysosomal iron reliance would prioritize modulation of autophagy or lysosomal function. Tumors that depend on elevated mitochondrial or lysosomal iron flux may therefore exhibit selective vulnerability to ferroptosis-inducing strategies[7,8].

Collectively, these observations indicate that ferroptotic iron does not originate from a single reservoir but emerges from dynamic, context-dependent exchange across organelles. Resolving this choreography will be essential for mechanistic clarity and the rational development of ferroptosis-based therapies.

THE CONTEXT PROBLEM: WHY FERROPTOSIS SENSITIVITY VARIES SO WIDELY ACROSS CELL TYPES, TISSUES, AND DISEASES

A defining feature of ferroptosis is the pronounced heterogeneity of cellular sensitivity. Kidney tubule epithelial cells, neurons, pancreatic acinar cells, and activated T cells are highly susceptible, whereas many cancer cells display marked resistance. Even within a given tissue, ferroptotic sensitivity varies with differentiation state, metabolic demand, oxygen availability, and microenvironmental stress, underscoring that ferroptosis arises from the integration of metabolic circuits and organellar defense systems rather than a single linear pathway.

The glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)-glutathione axis represents a central protective mechanism but functions within a multilayered antioxidant network[9-11]. GPX4-independent systems, most prominently apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondria-associated 2 (AIFM2/FSP1), suppress lipid radical propagation when GPX4 is compromised[12-14]. In parallel, lipid metabolic programs shape vulnerability: acyl-coenzyme A (CoA) synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4)-driven enrichment of polyunsaturated phospholipids promotes ferroptosis, whereas stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD)-mediated monounsaturated lipid synthesis confers resistance. Lysosomal homeostasis provides an additional regulatory layer, as disruptions in sphingolipid or cysteine metabolism can expand the labile iron pool or destabilize lysosomes[8,15].

These layers are coordinated by transcriptional regulators, particularly NFE2-like bZIP transcription factor 2 (NFE2L2), and reinforced by inter-organelle crosstalk that collectively reprogram redox capacity, lipid composition, and iron handling in a cell-type-specific manner. Cell identity and tissue architecture further modulate ferroptotic thresholds: epithelial-mesenchymal transition increases sensitivity, whereas high cell density and cell-cell adhesion suppress ferroptosis through reduced Yes-associated protein (YAP) and WW domain-containing transcription regulator 1 (TAZ) activity.

Resolving this contextual complexity will require high-resolution approaches capable of capturing ferroptosis at single-cell and subcellular scales. Emerging tools - including single-cell lipidomics, metabolic flux analysis, organelle-resolved redox sensors, and spatial metabolomics - are beginning to define the biochemical landscapes that dictate ferroptotic fate and will be essential for building a unified, context-aware framework of ferroptosis regulation.

THE BIOMARKER PROBLEM: THE FIELD STILL LACKS RELIABLE TOOLS TO DETECT FERROPTOSIS IN ANIMALS AND HUMANS

Although ferroptosis is well defined in vitro, its reliable detection in vivo remains a major barrier to clinical translation. Without robust biomarkers, it is difficult to determine whether ferroptosis is therapeutically induced, to predict toxicity, to stratify patients, or to establish whether ferroptosis is a causal driver rather than a secondary consequence of tissue injury.

Existing markers are informative but insufficiently specific. Classical lipid peroxidation readouts (e.g., malondialdehyde, 4-HNE, F₂-isoprostanes, oxidized low-density lipoprotein) reflect oxidative stress but not ferroptosis per se, whereas more selective oxidized phospholipids (e.g., PUFA-PE-OOH species) require advanced lipidomics and are not clinically tractable. Genetic, biochemical, or morphological indicators - including GPX4 loss, ACSL4 elevation, solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) suppression, or mitochondrial shrinkage - provide supportive evidence but lack diagnostic specificity.

A further challenge is that ferroptosis in vivo is likely focal, transient, and spatially heterogeneous, complicating detection in biofluids due to signal dilution and limiting the interpretability of single-time-point biopsies. Emerging imaging approaches, including 18F-(4S)-4-(3-fluoropropyl)-L-glutamate positron emission tomography (18F-FSPG PET), iron-sensitive probes, and peroxidation-responsive fluorophores, offer promise but currently lack specificity or clinical validation[16]. Similarly, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) or oxidized lipids, although commonly released during ferroptosis, are not specific to this death modality. Other candidates - including extracellular decorin (DCN) and released GPX4[17] - may more closely reflect ferroptotic injury, yet these signals also emerge in diverse inflammatory contexts, limiting their diagnostic precision.

Progress will require defining ferroptosis-specific molecular signatures and validating them using spatially and temporally resolved multi-omics, alongside the development of in vivo reporters capable of capturing lipid peroxidation dynamics. Until such tools are available, ferroptosis will remain easier to infer experimentally than to establish as a causal, clinically actionable process in human disease.

THE IMMUNOLOGY PROBLEM: FERROPTOSIS CAN BE INFLAMMATORY, IMMUNOGENIC, IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE, OR TOLEROGENIC - BUT WE DO NOT KNOW WHEN OR WHY

Ferroptosis does more than remove compromised cells; it actively remodels the immune landscape. Yet the immune signals it generates are highly context-dependent. In some settings, ferroptotic cells are strongly immunogenic, releasing oxidized lipids and DAMPs that activate innate immune pathways. In others, ferroptosis produces immunosuppressive cues (e.g., prostaglandin E2) that impair antigen presentation, inhibit T-cell function, promote regulatory myeloid programs, or directly deplete immune cell populations[18]. These divergent outcomes reflect inherent biological complexity rather than experimental variability.

This duality is most clearly illustrated in the tumor microenvironment. Early ferroptotic tumor cells can emit danger signals that engage dendritic cells and initiate immune priming. However, the same oxidized phospholipids and polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA)-derived eicosanoids that stimulate early activation can later disrupt dendritic cell cross-presentation and weaken cytotoxic T-cell responses. As ferroptotic cells decompose, their oxidized lipid-rich remnants often recruit myeloid precursors that differentiate into immunoregulatory macrophages, reinforcing an immunosuppressive niche. Together, these opposing effects help explain why ferroptosis can enhance, have no detectable impact on, or even counteract the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade, depending on tumor context, metabolic state, and the timing and extent of ferroptotic signaling.

Outside oncology, the picture is equally complex. Ferroptosis can aid pathogen clearance by amplifying inflammatory circuits, yet it may also remove critical immune cells and worsen susceptibility to infection. In sterile injury models, including acute pancreatitis and ischemia-reperfusion damage, ferroptosis promotes tissue destruction, but its inhibition does not uniformly improve repair, suggesting that ferroptotic signaling may also contribute to regeneration. In the nervous system, ferroptotic neurons may propagate oxidative stress across networks and activate microglia, although metabolic conditions can shift these signals toward immunosuppression.

Multiple factors likely dictate these divergent outcomes, including the oxidation state of released lipids, the identity of the ferroptotic cell, the redox environment of the surrounding tissue, and the timing of membrane breakdown. Endogenous lipid-binding proteins such as apolipoprotein E (APOE) and albumin may further buffer or reshape immune recognition of ferroptotic debris[19].

This unresolved immunological ambiguity remains a major obstacle to therapeutic translation. Predicting when ferroptosis will activate immunity versus when it will dampen it requires mechanistic clarity that the field does not yet possess. Moving forward, integrated in vivo studies combining immunometabolism, redox lipidomics, and spatial immunophenotyping will be essential for defining how ferroptosis communicates with the immune system. Only with such insight can ferroptosis be harnessed in a way that reliably complements, rather than conflicts with, immune-based therapies.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

Ferroptosis now occupies a central position in discussions of cancer biology, tissue injury, and immune regulation, yet its clinical translation remains limited by several unresolved conceptual gaps. Although the field has assembled an extensive catalogue of regulators and metabolic dependencies, persistent uncertainty surrounding execution, iron mobilization, context specificity, in vivo detection, and immunological consequences continues to constrain predictive and therapeutic precision.

Importantly, these unresolved questions manifest differently across disease classes, reflecting distinct cellular states and metabolic constraints. In oncology, ferroptosis vulnerability is shaped by oncogenic metabolism, lipid composition, iron acquisition, and microenvironmental pressures such as hypoxia and immune surveillance, with certain cancers - notably kidney and pancreatic cancers - showing heightened sensitivity to ferroptosis-based interventions. In neurodegenerative diseases, susceptibility is driven by post-mitotic cell status, chronic iron redistribution, membrane lipid vulnerability, and sustained neuroinflammation, whereas in sterile inflammatory conditions, ferroptosis is often triggered by acute metabolic collapse, redox imbalance, and localized iron release. Thus, although shared mechanistic principles underlie ferroptosis, their relative importance and translational relevance are inherently disease specific.

Addressing these gaps will require coordinated advances across multiple fronts. Defining ferroptosis execution and iron dynamics will depend on integrating membrane biophysics with high-resolution, organelle-resolved iron imaging, while context dependence can be resolved using single-cell and spatial multi-omics approaches that link metabolic and lipid states to ferroptotic outcomes. Progress in translation will further require ferroptosis-specific in vivo biomarkers and temporally resolved models to define its immunological consequences.

Together, these advances point toward a more predictive and disease-tailored framework for ferroptosis research. In cancer, strategies that selectively induce ferroptosis in malignant cells - while preserving immune and normal tissue integrity - offer a rational path to enhance antitumor immunity and therapeutic durability[20]. By integrating mechanistic rigor with disease-specific insight, the field is poised to transform ferroptosis from a compelling biological concept into a precise and clinically actionable therapeutic modality.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the significant and rapid contributions of our colleagues to the field of ferroptosis research and regret that space limitations preclude a comprehensive discussion of all recent advances.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to discussions, writing, and critical revision of all sections of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Dixon, S. J. et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149, 1060-72 (2012).

2. Dai, E. et al. A guideline on the molecular ecosystem regulating ferroptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 26, 1447-57 (2024).

3. Brown, A. R.; Hirschhorn, T.; Stockwell, B. R. Ferroptosis-disease perils and therapeutic promise. Science 386, 848-9 (2024).

4. Ramos, S.; Hartenian, E.; Santos, J. C.; Walch, P.; Broz, P. NINJ1 induces plasma membrane rupture and release of damage-associated molecular pattern molecules during ferroptosis. EMBO J 43,1164-86 (2024).

5. Hirata, Y. et al. Lipid peroxidation increases membrane tension, Piezo1 gating, and cation permeability to execute ferroptosis. Curr. Biol. 33,1282-94.e5 (2023).

6. Zhuang, X. et al. Ageing limits stemness and tumorigenesis by reprogramming iron homeostasis. Nature 637, 184-94 (2025).

7. Chen, Y. et al. Oxidative stress induces mitochondrial iron overload and ferroptotic cell death. Sci. Rep. 13, 15515 (2023).

8. Cañeque, T. et al. Activation of lysosomal iron triggers ferroptosis in cancer. Nature 642, 492-500 (2025).

10. Lorenz, S. M. et al. A fin-loop-like structure in GPX4 underlies neuroprotection from ferroptosis. Online ahead of print. Cell S0092-8674(25)01310-8 (2025).

11. Hu, Y. et al. Targeting PRDX6-dependent localization and function of GPX4 enhances ferroptosis-mediated tumor suppression. Mol. Cell 85, 4602-20.e9 (2025).

12. Yang, J. S. et al. ALDH7A1 protects against ferroptosis by generating membrane NADH and regulating FSP1. Cell 188, 2569-85.e20 (2025).

13. Palma, M. et al. Lymph node environment drives FSP1 targetability in metastasizing melanoma. Online ahead of print. Nature (2025).[PMID41193799 DOI:10.1038/s41586-025-09709-1].

14. Wu, K. et al. Targeting FSP1 triggers ferroptosis in lung cancer. Online ahead of print. Nature (2025).

15. Swanda, R. V. et al. Lysosomal cystine governs ferroptosis sensitivity in cancer via cysteine stress response. Mol. Cell 83, 3347-59.e9 (2023).

16. Park, S. Y. et al. Clinical evaluation of (4S)-4-(3-[18F]Fluoropropyl)-L-glutamate (18F-FSPG) for PET/CT imaging in patients with newly diagnosed and recurrent prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 5380-7 (2020).

17. Liu, L. et al. Extracellular GPX4 impairs antitumor immunity via dendritic ZP3 receptors. Available on February 19, 2026. Cell 189, 1-18 (2026).

18. Morgan, P. K. et al. A lipid atlas of human and mouse immune cells provides insights into ferroptosis susceptibility. Nat. Cell Biol. 26, 645-59 (2024).

19. Belaidi, A. A. et al. Apolipoprotein E potently inhibits ferroptosis by blocking ferritinophagy. Mol. Psychiatry 29, 211-20 (2024).

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

Article Notes

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].