Acetaminophen, autism, and the evidence gap: a call for scientific rigor

Abstract

Recent claims linking prenatal acetaminophen (paracetamol, brand name Tylenol) use to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are outpacing the science, raising public concern without robust causal evidence. This article argues that adopting this methodologically flawed hypothesis poses a dual threat: it risks shaping public health policy based on conjecture and stigmatizing a medication vital for managing pain and fever during pregnancy. Using the frameworks of causal inference and evidence-based medicine, we evaluate the limited data, re-emphasize the established multifactorial nature of ASD, and caution against abandoning risk-benefit analysis in prenatal care. We conclude that elevating this unvalidated claim to guide clinical practice is scientifically unsound and detrimental to maternal and fetal health. Public health decisions must remain grounded in rigorous evidence, not fear.

Keywords: acetaminophen, paracetamol, tylenol, autism spectrum disorder, prenatal medication safety, public health

The rising prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has made it a priority for global public health, yet its etiology remains incompletely understood. Against this backdrop, claims suggesting a potential link between prenatal acetaminophen use and ASD have sparked widespread concern among the public and scientific community - largely because such assertions lack robust empirical support. Acetaminophen is a cornerstone of prenatal pain and fever management; unfounded warnings about its safety could disrupt clinical practice and inadvertently harm maternal-fetal health.

This paper aims to systematically evaluate the scientific validity of existing claims, ground the discussion in ASD’s clinical and epidemiological reality, and advocate for evidence-based policy and clinical practice - with a focus on advancing public health priorities rather than speculative assertions.

THE COMPLEXITY OF AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER

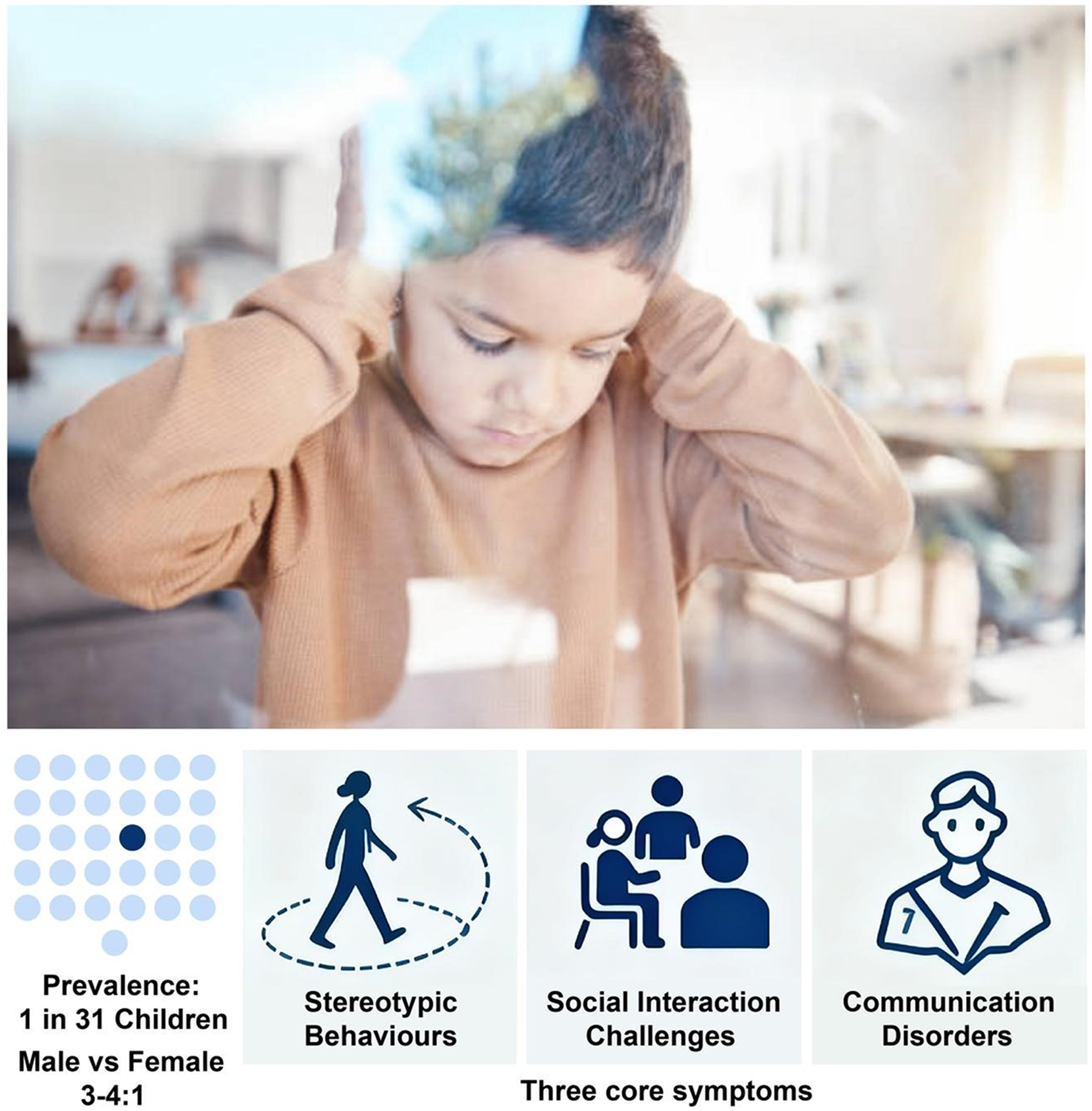

ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder defined by two core symptom domains: persistent impairments in social communication and interaction (e.g., difficulty with reciprocal conversation, misinterpreting nonverbal cues such as facial expressions or body language) and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities (e.g., stereotyped movements, inflexible adherence to daily routines)[1]. The term “spectrum” underscores its marked heterogeneity: some individuals with ASD are nonverbal and require lifelong intensive support for activities of daily living, while others exhibit intact language skills but struggle with subtle social nuances (e.g., understanding sarcasm or contextual social expectations).

Epidemiological data on ASD are striking. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports a current prevalence of approximately 1 in 31 children, a significant increase from the 1 in 150 estimate two decades ago[2]. This upward trend is multifactorial and not fully explained by a single factor: broader diagnostic criteria [e.g., the integration of previously distinct diagnoses such as Asperger’s syndrome under the unified ASD umbrella in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fifth Edition (DSM-5)] have expanded case identification; improved public awareness and widespread adoption of early screening tools (e.g., the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, MCHAT) have enabled earlier detection; and emerging evidence suggests environmental factors (e.g., prenatal exposure to air pollution, maternal metabolic disorders) may interact with genetic susceptibility to contribute to ASD risk - though the specific mechanisms of this interaction remain unclear. The key statistics and core symptom domains of ASD are summarized in Figure 1.

The scientific community uniformly recognizes ASD as a multifactorial disorder. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified hundreds of genes associated with ASD risk, including rare copy number variations (CNVs) that disrupt neurodevelopmental pathways. However, no single gene or genetic variant accounts for ASD onset; instead, ASD arises from the interplay of genetic predispositions and environmental influences during the critical window of early brain development (from conception to 2 years of age). This complexity underscores why isolated claims of a single environmental trigger - such as prenatal medication use - require extraordinary evidence to be validated[3].

Recent genetic evidence dismantles the notion of a single ‘autism’. A landmark study by Zhang et al. (Nature, 2025) reveals that early- and late-diagnosed ASD have distinct genetic architectures and developmental pathways[4]. Crucially, later-diagnosed ASD demonstrates a stronger genetic link to other neurodevelopmental and mental health conditions. This provides a biological explanation for the clinical spectrum of ASD and confirms that the single diagnostic label of ASD masks what are, in fact, etiologically distinct subtypes.

THE FALLACY OF EQUATING ASSOCIATION WITH CAUSATION

Claims linking prenatal acetaminophen use to ASD rely primarily on observational studies, most notably a 2025 systematic review that reported a “correlation between prolonged prenatal acetaminophen exposure and a modest increase in ASD risk”[5]. While such statistical associations merit careful scientific inquiry, they are not equivalent to causation - and thus cannot serve as a basis for public health policy. Observational studies excel at identifying potential relationships but are inherently limited by their inability to rule out alternative explanations, particularly confounding variables.

A major limitation of these observational data is “confounding by indication”: the conditions that prompt acetaminophen use in pregnant individuals - such as persistent maternal fever (≥ 38.5 °C), urinary tract infections, or inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis - are themselves independent risk factors for adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring[6-8]. The genetic insights from Zhang et al. offer a powerful mechanistic explanation for this link[4]. Their work demonstrates that the genetic predisposition for later-diagnosed ASD is shared with predispositions for common maternal conditions, such as anxiety, chronic pain, and inflammation. Therefore, an observed association between acetaminophen and ASD is likely non-causal; it is more plausibly an artifact of this shared genetic liability, where the medication is a bystander, not the cause. This mechanism is supported by established research on the impact of maternal health on fetal development: for example, a 2016 Science study demonstrated that maternal immune activation disrupts fetal brain development, leading to ASD-like phenotypes in animal models[9]. Similarly, a Swedish cohort study of nearly 2 million individuals found that maternal infection during pregnancy was associated with a 1.3-fold increased risk of psychotic disorders in offspring, highlighting the profound impact of maternal illness on fetal neurodevelopment[10]. These findings strongly suggest that the observed “association” between acetaminophen and ASD may reflect the effects of underlying maternal conditions - not the drug itself.

A 2024 large-scale sibling-controlled study published in JAMA directly addressed this confounding issue, providing more robust evidence. The study analyzed 68,584 sibling pairs from Swedish national registers, comparing siblings exposed to prenatal acetaminophen with unexposed siblings within the same family. By controlling for shared genetic factors (e.g., parental genotypes) and family-level environmental factors (e.g., socioeconomic status, household living conditions), the study eliminated the previously observed association between acetaminophen and ASD [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 0.98, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.89-1.08][11]. This rigorous design - unique in its ability to account for unmeasured familial confounders - confirms that earlier observational associations are likely driven by confounding variables, not acetaminophen exposure itself.

THE DANGER OF NEGLECTING RISK-BENEFIT ANALYSIS

Acetaminophen is the first-line analgesic and antipyretic for pregnant individuals, with a safety profile established through decades of clinical practice and post-marketing surveillance[12]. Its status as a preferred medication stems from the well-documented risks of alternative options: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and naproxen are contraindicated in the third trimester, as they inhibit prostaglandin synthesis and can cause premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus - a condition linked to severe neonatal pulmonary hypertension. A 2006 meta-analysis reported a 2.7-fold increased risk of ductus arteriosus closure in infants exposed to NSAIDs in the third trimester (95%CI: 1.8-4.1)[13]. Opioid analgesics, another alternative for pain management, carry significant risks of maternal addiction and neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS), precluding their routine use in pregnancy[14].

Labeling acetaminophen as “risky” without sufficient evidence ignores the substantial harms of untreated pain and fever during pregnancy. Unsubstantiated warnings about acetaminophen could lead pregnant individuals to avoid the drug, either leaving their symptoms untreated or turning to unsafe alternative medications. This replaces a hypothetical, unproven risk with a known, significant threat to maternal and fetal health - an outcome driven by excessive caution rather than scientific evidence, and one that directly contradicts public health’s core mission of minimizing harm.

A PATH FORWARD: FROM CONJECTURE TO RIGOROUS SCIENCE

Given the uncertain and conflicting evidence - particularly the absence of a proven causal link between acetaminophen and ASD - the scientific and ethical response must prioritize rigorous research and balanced communication, not policy based on speculation. This approach not only addresses the current question of acetaminophen safety but also establishes a framework for resolving future uncertainties in prenatal medication use.

First, mechanistic research should prioritize human-relevant models to explore biological plausibility. Funding could support studies using induced human pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons and brain organoids - systems that better recapitulate human neurodevelopment than traditional animal models - to investigate whether acetaminophen or its metabolites [e.g., N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI)] disrupt key neurodevelopmental processes (e.g., neuronal proliferation, synaptogenesis). This focus on human-centric models ensures that findings are more likely to translate to clinical reality; if such studies fail to identify a plausible mechanism, extensive animal testing may be unnecessary, aligning with the principles of rigorous, efficient research.

Second, we must leverage genetic data to cut through the confounding that plagues observational studies. While methods such as Mendelian randomization hold promise, our work and that of Zhang et al. (Nature, 2025) reveal a more immediate solution: using genetics to account for outcome heterogeneity[4]. Their research proves that “ASD” is not a single condition but an umbrella for etiologically distinct subtypes. Future studies must therefore move beyond treating ASD as a unitary outcome. By incorporating polygenic scores for specific subtypes, particularly those such as later-diagnosed ASD, that share genetic roots with maternal conditions - researchers can perform a kind of “genetic deconfounding”. This powerful approach isolates the signal of a medication from the noise of shared genetic liability, finally allowing for robust causal inference.

Third, advanced epidemiological designs are essential to strengthen causal inference. Priority should be given to large-scale prospective cohort studies with objective exposure assessment (e.g., pharmacy dispensation records, maternal blood or urine acetaminophen levels) to reduce recall bias - a common limitation of self-reported exposure data. Innovative methods such as Mendelian randomization, which uses genetic variants associated with acetaminophen metabolism [e.g., Cytochrome P-450 2E1 (CYP2E1) polymorphisms] as “instrumental variables”, can further minimize confounding by accounting for unmeasured individual differences, improving the reliability of causal claims.

Fourth, balanced clinical communication is key to guiding practice. Clinicians should receive evidence-based guidelines clarifying that current evidence does not establish a clear risk between prenatal acetaminophen use and ASD when the drug is administered at the lowest effective dose for the shortest necessary duration. Patient education materials should similarly frame the evidence objectively: emphasizing both the lack of conclusive data linking acetaminophen to ASD and the known risks of untreated fever or pain. This approach empowers shared decision-making between clinicians and pregnant individuals, rather than sowing unnecessary alarm.

CONCLUSION

While the urgency to address the rising prevalence of ASD is understandable, elevating a methodologically flawed, controversial hypothesis to policy-level guidance is scientifically unsound and ethically questionable. Such actions disregard the hierarchy of evidence - where large, well-controlled studies (e.g., the 2024 JAMA sibling study) carry far more weight than observational associations - and threaten the role of a critical medication in prenatal care.

More broadly, this episode underscores a fundamental principle of public health: scientific conjecture, particularly when based on limited or conflicting evidence and lacking a proven mechanistic link, must not be translated into definitive policy or official statements. Administrative and clinical decisions must be guided by the weight of rigorous evidence to prevent unnecessary public concern and potential harm.

True scientific caution in public health requires adhering to evidence-based principles, balancing risks and benefits, and protecting the public from both known harms and premature policy. As scientific research is dynamic, future evidence may revise our current understanding of acetaminophen and ASD - and we must remain open to such updates. Until then, public health policy and clinical practice must be guided by rigorous science - not speculation that could compromise the health of pregnant individuals and their offspring.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the concept and outlined the framework: Wang, Z.; Wang, F.

Drafted the manuscript: Wang, Z.; Wang, F.

Contributed to critical revision, provided intellectual guidance: Wang, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Zhen, X.; Li, N.; Xie, W.; Jiao, J.; Wang, F.

All authors made substantial contributions to this correspondence, and approved the final version for publication.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

Wang, F. is the Editor-in-Chief of the journal Element. Wang, F. was not involved in any steps of editorial processing, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling and decision making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

2. Shaw, K. et al. Prevalence and early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 and 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 16 sites, United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 74, 1-22 (2025).

3. Emberti Gialloreti, L. et al. Risk and protective environmental factors associated with autism spectrum disorder: evidence-based principles and recommendations. J. Clin. Med. 8, 217 (2019).

4. Zhang, X. et al; APEX Consortium, iPSYCH Autism Consortium, PGC-PTSD Consortium. Polygenic and developmental profiles of autism differ by age at diagnosis. Nature (2025).

5. Prada, D. et al. Evaluation of the evidence on acetaminophen use and neurodevelopmental disorders using the Navigation Guide methodology. Environ. Health 24, 56 (2025).

6. O’Callaghan, E. et al. Schizophrenia after prenatal exposure to 1957 A2 influenza epidemic. Lancet 337, 1248-50 (1991).

7. Babulas, V. et al. Prenatal exposure to maternal genital and reproductive infections and adult schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 163, 927-9 (2006).

8. Brown, A. S. et al. Elevated maternal interleukin-8 levels and risk of schizophrenia in adult offspring. Am. J. Psychiatry 161, 889-95 (2004).

9. Estes, M. L. et al. Maternal immune activation: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Science 353, 772-7 (2016).

10. Blomström, Å. et al. Associations between maternal infection during pregnancy, childhood infections, and the risk of subsequent psychotic disorder - a Swedish cohort study of nearly 2 million individuals. Schizophr. Bull. 42, 125-33 (2016).

11. Ahlqvist, V.H. et al. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy and children’s risk of autism, ADHD, and intellectual disability. JAMA. 331, 1205-14 (2024).

12. Patel, R. et al. Long-term safety of prenatal and neonatal exposure to paracetamol: a systematic review. Int. J Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 2128 (2022).

13. Koren, G. et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs during third trimester and the risk of premature closure of the ductus arteriosus: a meta-analysis. Ann. Pharmacother 40, 824-9 (2006).

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

Article Notes

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].