Palladium single-atom catalysts prepared via strong metal-support interaction for selective 1,3-butadiene hydrogenation

Abstract

Selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene to butenes is an effective way to eliminate the minor 1,3-butadiene impurities, which can cause intractable issues of catalyst deactivation in the C4 olefins upgrading processes. To this end, Pd single-atom catalysts (SACs) exhibit remarkable selectivity to desired butene products due to the adsorption configuration of 1,3-butadiene in a mono-π mode. However, it is still a grand challenge to prepare thermally stable Pd SACs with conventional synthetic methods. Herein, we acquired Pd SACs via the selective encapsulation strategy exploiting classical strong metal-support interaction, during which Pd nanoparticles are more prone to be encapsulated by the oxide overlayer than Pd single atoms, thus Pd single atoms exclusively stay exposed to the catalytic environment. Various characterizations, such as aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy, electron energy loss spectroscopy, together with CO adsorbed in-situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectra, have collectively demonstrated the successful synthesis of Pd SACs on CeO2 support when we adjusted the reductive temperature to 600 °C (Pd/CeO2-H600). The as-obtained Pd/CeO2-H600 gives excellent catalytic performances in the selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene with conversion of almost 100% and butenes selectivity of above 98% at 100 °C. Moreover, the conversion of 99% and butenes selectivity of 97.5% can also remain nearly unchanged for 60 h at a weight hourly space velocity of 60,000 mL/gcat/h. This work illustrates the effectiveness of this selective encapsulation strategy to construct Pd SACs and can probably provide a prospective avenue to prepare various SACs for selective hydrogenation processes.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Fluidized catalytic cracker (FCC) unit is a significant processing segment in the petroleum refinery process for the production of light olefins from crude oil, especially C4 cuts, such as 1-butene and isobutenes[1]. Subsequently, the refined C4 olefins can either be converted to longer-chain linear alpha olefins via oligomerization process for producing the versatile plasticizer alcohols[2,3] or be directly valorized into value-added ethers or alcohols[4]. However, during the above upgrading processes, the concomitant 1,3-butadiene by-products originating from the FCC unit can cause intractable issues of catalyst deactivation for the downstream processes due to the formation of undesirable oligomers or polymers[5]. Thereupon, the concentration of 1,3-butadiene should be rigorously controlled below 200 ppm. To this end, one effective strategy is the selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene to butenes[6]. In general, Pd-based catalysts are widely applied in this field due to their intrinsically high hydrogenation activity[7-11]. Nevertheless, Pd monometallic catalysts often suffer from low alkene selectivity at high conversions while the bimetallic counterparts require precisely manipulating the compositions of the active sites and phase of catalytic supports for attaining high alkene selectivity, thus posing challenges for the potential large-scale utilization.

Single-atom catalysts (SACs) have gained enormous attention since this concept was coined a decade ago because SACs bear theoretically maximum atom utilization and also demonstrate advantageous catalytic properties in comparison with nanoparticulate catalysts[12-15]. The unique monomolecular and isolated configurations of supported single atoms can greatly alter the adsorption mode of the reactants, thus exhibiting characteristic catalytic selectivity in, for example, 1,3-butadiene hydrogenation. In this regard, Yan et al. have previously revealed the mono-π-adsorption mode of 1,3-butadiene on the supported Pd SACs, over which nearly 100% butenes selectivity could be achieved at conversions of above 95% under mild reaction conditions[16-18]. However, although various synthesis strategies, such as wet chemistry, atomic layer deposition and atom trapping, have been devised for successfully synthesizing SACs, the thermal instability of Pd-based SACs, especially on the oxide supports, remains tricky[19-27].

Strong metal-support interaction (SMSI) was first discovered by Tauster et al. in the 1970s, referring to the phenomenon where deposited metal nanoparticles are gradually encapsulated by an overlayer of reduced oxide migrated from the adjacent reducible oxide support under a reductive atmosphere at high temperatures[28,29]. With the development of various novel SMSI processes, these experimental results have potential for improving the catalytic stability[30-39]. Recently, our group has found that classical SMSI, apart from occurring on the traditional metal nanoparticles, could also be induced on the supported single-atom system, such as Pt1/TiO2 SACs, at temperatures higher than that over the nanoparticulate one[40]. By this means, we could selectively encapsulate the co-existed nanoparticles while the single atoms on the supports still remained exclusively exposed and reactive for the catalytic processes, thus acquiring stable SACs[41].

Herein, we employed this strategy to construct stable Pd SACs through high-temperature reduction treatment of the corresponding supported Pd catalysts prepared with conventional wet-chemistry method. The as-obtained Pd SACs were then subjected to 1,3-butadiene hydrogenation and consequently exhibited excellent butenes selectivity of nearly 100% at conversion of as high as above 98%. Moreover, the catalytic stability could be maintained for 60 h at high temperature of 110 °C, which signals prospective applications of this synthetic strategy to get stable SACs for selective hydrogenation processes.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

All chemicals were commercially available and were not further pretreated. Cerium(III) nitrate [Ce(NO3)3·

Synthesis of CeO2 support

The CeO2 support was prepared by a co-precipitation method. At room temperature, an aqueous solution of Ce(NO3)3·6H2O (1 mol/L) was continuously added to an aqueous solution of Na2CO3 (1 mol/L) by a constant-flow pump and stirred continuously until the final pH of the aqueous solution reached 7-8. Then, after 3 h of constant stirring and aging, respectively, the solution was filtered by pumping using a Büchner funnel, and washed with deionized water 2-3 times. The recovered solid was dried at 60 °C and then calcined at 400 °C for 5 h to obtain the CeO2 support.

Synthesis of 1.0 wt% Pd/CeO2

Pd/CeO2 was prepared by a conventional adsorption method. In detail, 1 g of the previously prepared CeO2 support powder was dispersed into 50 mL of deionized water with constant stirring. A solution of 0.27 mL of 10 wt% Pd(NO3)2·4NH3 was added to the suspension of CeO2 support. Then, the suspension was stirred at 600 r for 6 h and aged for another 2 h. The suspension was filtered using a funnel and washed with deionized water 2-3 times. The recovered solid was dried at 60 °C and then calcined at 400 °C for 5 h. The synthesized catalyst was denoted as Pd/CeO2. Pd/CeO2 was reduced under 10 vol.% H2/He at different temperatures named Pd/CeO2-Hx (x represents the H2 treatment temperature). Besides, the Pd/CeO2-H600 catalyst was re-oxidized under 20 vol.% O2/He at 500 °C, denoted as Pd/CeO2-H600-O500.

Characterization method

The palladium loading was quantified through inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) using a Shimadzu ICPS-8100 system (Shimadzu Co., Ltd.). Approximately 10 mg of catalyst samples underwent microwave-assisted digestion with aqua regia (3:1 v/v HCl:HNO3 mixture) in sealed vessels to achieve complete dissolution. Crystalline phase analysis was conducted via X-ray diffraction (XRD) with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.15432 nm), operating at 40 kV and 40 mA with a 0.02° step resolution. Microstructural characterization employed aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-STEM) and electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) on a JEOL JEM-ARM200F microscope (200 kV) integrated with a Gatan Quantum 965 image filtering system. Surface coverage analysis involved direct electron beam irradiation on Pd species in STEM mode. Specimen preparation included ultrasonic dispersion in anhydrous ethanol followed by deposition onto copper grids. In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) measurements utilized a Bruker VERTEX 70V spectrometer with a diffuse reflectance accessory, accumulating 32 scans at 4 cm-1 resolution. Pretreatment protocols comprised: (1) 30-minute 4% H2/He flow at 200 °C; (2) 5-minute He purging to eliminate surface-bound H2; and (3) background signal acquisition after cooling to ambient temperature. CO adsorption proceeded under 5% CO/He flow until spectral stabilization, followed by He flushing to exclude gaseous CO before spectral recording. Surface composition analysis was performed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi) with Al Kα excitation (1,486.8 eV). Thermogravimetric profiles were acquired on a NETZSCH STA 449 F3 analyzer under O2 flow: initial heating to 150 °C (5 °C/min ramp) with 30-minute isothermal holding for dehydration, followed by continuous heating to 800 °C for mass loss monitoring.

Catalytic performance evaluation

Selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene over different catalysts was evaluated in a quartz fixed bed reaction gas with 50 mg catalyst. The catalyst was first pre-reduced under 10 vol.% H2 (30 mL/min) at different temperatures. After waiting for the catalyst to be cooled to room temperature, the feed gas 1 vol.% butadiene, 6 vol.% H2 and He balance was introduced into the fixed bed reactor at different test temperatures.

Gas compound was analyzed by on-line GC equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and a PORAPAK-N column using He as carrier gas. The conversion of butadiene and the selectivity of 1-butene were calculated as:

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The pristine supported Pd catalysts, denoted as Pd/CeO2, were synthesized with the conventional adsorption method. Afterwards, the as-obtained Pd/CeO2 catalysts were post-treated under 10 vol.% H2/He atmosphere at different temperatures and the resulting samples were marked as Pd/CeO2-Hx, where x represents the H2 treatment temperature. Structural analysis of the CeO2 support through various characterizations revealed its characteristic fluorite-type crystalline architecture with conventional specific surface area of about 128 m2/g [Supplementary Figures 1 and 2]. The actual Pd loading of the above samples is determined to be around 0.70 wt% by the ICP-OES analysis, which suggests no obvious Pd loss during the calcination and reductive treatment processes. There are only diffraction peaks of CeO2 in the XRD patterns of different samples, and the absence of diffraction peaks ascribed to metallic Pd or PdO indicates the high dispersion of Pd species on CeO2 supports [Supplementary Figure 3].

Mass transport from oxide support to the deposited metal nanoparticles is the typical characteristic when classical SMSI phenomenon occurs [Figure 1A] and we directly observed the final state of Pd/CeO2 after high-temperature reductive treatment via aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-HAADF-STEM) and EELS. As shown in Figure 1B, it is apparent that a thin and translucent overlayer covers the Pd nanoparticles of Pd/CeO2-H600 sample. Furthermore, one micro-area of the overlayer (area II in Figure 1B) is selected to discern the composition and the analysis unambiguously confirms that the overlayer is composed of CeOx species [Figure 1C], suggesting the occurrence of classical SMSI on Pd nanoparticles[42,43]. Further examination of STEM images reveals the mean size of around 9 nm for Pd nanoparticles [Supplementary Figure 4]. Moreover, it is worthwhile to mention that due to the low contrast between Pd atoms and CeO2 support, Pd single atoms are difficult to clearly detect in AC-HAADF-STEM images.

Figure 1. (A) Schematic illustration of SMSI over Pd/CeO2; (B) AC-HAADF-STEM image and (C) the corresponding EELS spectra of Pd/CeO2-H600. SMSI: Strong metal-support interaction; AC-HAADF-STEM: aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy; EELS: electron energy loss spectroscopy.

DRIFTS of CO adsorption (CO-DRIFTS) is an effective technique for characterizing SMSI phenomena and can meanwhile supplement the unavailable information from STEM due to the sensitivity to probe the geometric and electronic properties of active sites. Thus, CO-DRIFTS was further conducted to illustrate more structural transformations during SMSI. Generally, apart from the doublet peaks centered at around 2,170 and 2,120 cm-1 attributed to gaseous CO, the other three peaks can possibly be ascertained when CO adsorbs on Pd species. The strong peak at around 2,060 cm-1 and the broad peak in the range from 1,800 to 1,990 cm-1 are ascribed to CO molecules linearly and bridged adsorbed on Pd nanoparticles, respectively[44]. Besides, the peak at around 2,113 cm-1 is the characteristic sign of linear CO adsorption on single Pd atoms[45], yet this adsorption mode is somewhat overlapped with gaseous CO peak at 2,120 cm-1. Therefore, to distinguish the Pd single atoms in the sample, the desorption rate of CO should be carefully controlled and meanwhile we also need to pay attention to whether the peak resulting from CO bridged adsorbed on Pd nanoparticles exists. When pristine Pd/CeO2 is reductive treated at low temperature of 200 °C [Figure 2A], it is apparent that both linear and bridged CO adsorption on Pd nanoparticles appear and a weak linear CO adsorption on Pd single atoms can be observed, thus indicating the co-existence of Pd single atoms and Pd nanoparticles in the Pd/CeO2-H200. After further increasing the reduction temperature to 300 °C, the peak intensity of CO adsorbed on Pd nanoparticles wanes [Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure 5]. This sign is in accordance with the gradual encapsulation of Pd nanoparticles by CeOx layer when increasing the reduction temperature. When the reduction temperature was controlled to 600 °C, the corresponding spectral analysis only identifies overlapping vibrational features between gaseous CO (centered at 2,120 cm-1) and CO chemisorbed on isolated Pd atoms (centered at 2,112 cm-1). Therefore, the two gaseous CO peaks exhibit distinct attenuation behaviors. Compared with the peak at 2,173 cm-1, the peak at 2,120 cm-1 exhibits relatively slower attenuation, due to the trace amount of CO chemisorbed on Pd single atoms remaining during the He purging process. Quantitative analysis of integrated peak areas for the two gas-phase CO adsorption bands also reveals a much higher area ratio between peaks centered at 2,120 and 2,173 cm-1 in the Pd/CeO2-H600 catalyst compared to the H200 and H300 samples [Supplementary Figure 6], further demonstrating the predominantly remaining CO-Pd1 species during He purging. Besides, the absence of CO linear adsorption peaks characteristic of Pd nanoparticles can confirm that Pd species exclusively exist as single atoms on the CeO2 support [Figure 2C]. It is worth mentioning that the mass transport process of SMSI is reversible. When the oxidation treatment is applied to the samples with an encapsulation layer on the metal nanoparticles, the as-described overlayer can retreat and the metal nanoparticles gradually expose. Therefore, we also examined this process via CO-DRIFTS. After calcination at 500 °C under an oxygen atmosphere for reversible re-oxidation treatment [Figure 2D], the peaks ascribed to the CO molecules adsorbed on Pd nanoparticles appear again, and these peaks slightly shift to a higher wavenumber, thus indicating the electron transport between Pd species and CeO2 support. Moreover, the CO-DRIFTS spectra of Pd/CeO2-H600-O500 barely change after reductive treatment again at a low temperature of 200 °C, showing relatively stable Pd-CeOx interactions [Supplementary Figure 7].

Figure 2. CO-DRIFTS spectra at saturation CO coverage followed by He purging of (A) Pd/CeO2-H200, (B) Pd/CeO2-H300, (C) Pd/CeO2-H600 and (D) Pd/CeO2-H600-O500 samples. CO-DRIFTS: Diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy of CO adsorption.

In-situ XPS was also carried out to determine the reversible electron transfer between Pd species and CeO2 support during the reductive and re-oxidative treatment for SMSI. As shown in Figure 3A, the Pd species in Pd/CeO2 shows a binding energy of 337.7 eV and this can be assigned to (2 < δ ≤ 4) with a form of interfacial PdxCe1-xO2[46-48]. After reductive treatment at 300 °C, the Pd 3d5/2 peak can be deconvoluted into 337.6 eV and a peak with a lower binding energy of 335.8 eV [Figure 3B], demonstrating that the Pd species consist of metallic Pd0 and PdOx in an oxidation Pdδ+ state[49]. Furthermore, the peak area ratio between Pd0 and Pdδ+ increases at reduction temperature of 600 °C and the Pd 3d5/2 peak assigned to Pdδ+ further decreases to

Figure 3. In-situ XPS spectra of (A) Pd/CeO2, (B) Pd/CeO2-H300, (C) Pd/CeO2-H600 and (D) Pd/CeO2-H600-O500. XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.

Abovementioned characterizations collectively prove the occurrence of SMSI between Pd species and CeO2 and Pd nanoparticles are more prone to be covered than Pd single atoms. Therefore, Pd SACs can be acquired by selectively encapsulating Pd nanoparticles while the remaining Pd single atoms are still exposed to the catalytic environment. As reviewed above, selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene to butenes is of great significance in both academic and industrial applications, and the resulting butenes selectivity is very sensitive to whether the Pd species is in an isolated or agglomerated state[16,17]. As a consequence, we can reasonably speculate the improved butenes selectivity in the Pd/CeO2 system with SMSI.

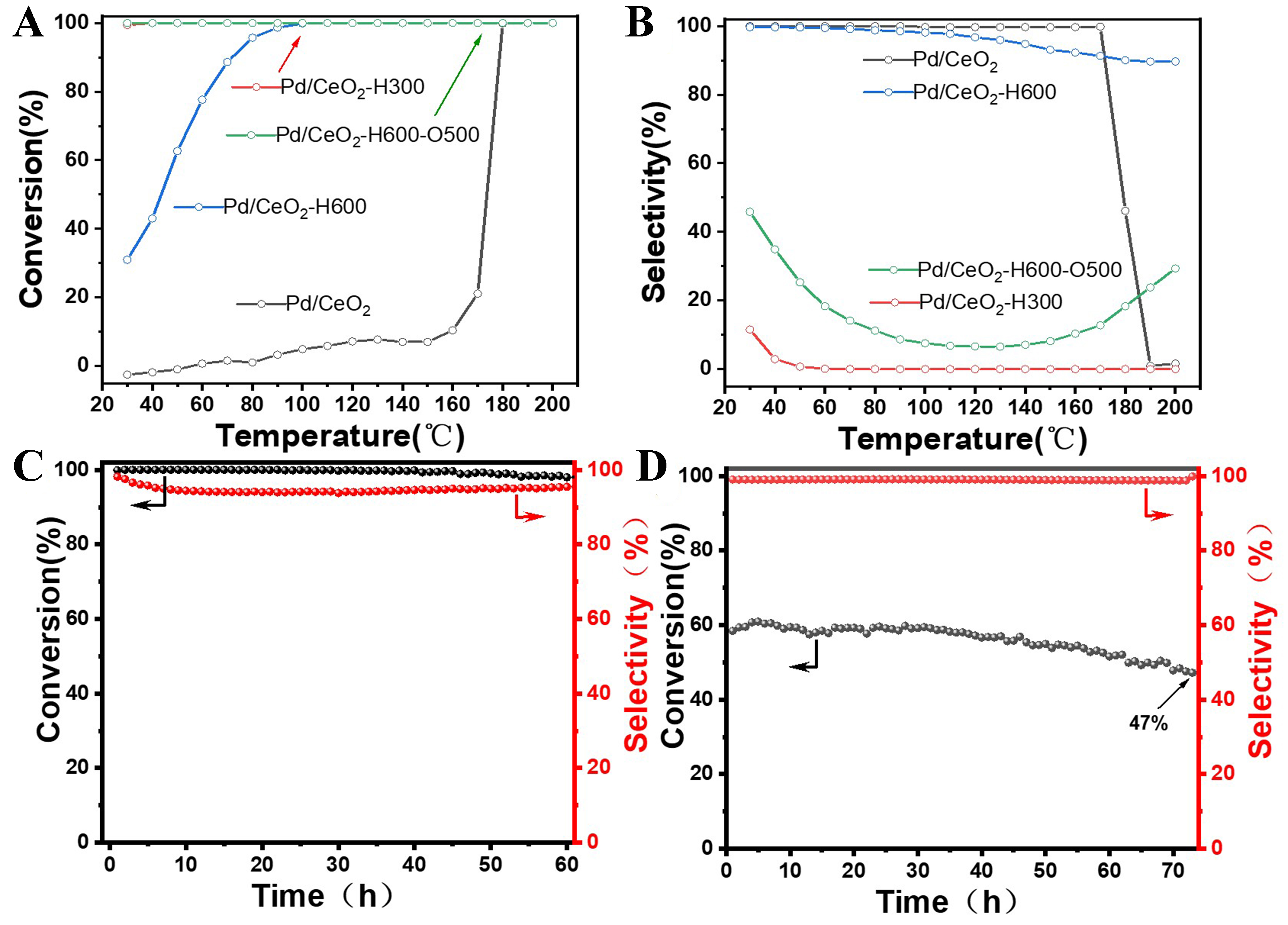

The selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene was performed below 200 °C at a weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 60,000 mL/gcat/h over the series of Pd/CeO2 catalysts. A blank test over partially reduced CeO2 support and the bare CeO2 almost exhibited no detectable activity for this specific reaction [Supplementary Figure 8]. As shown in Figure 4A and B, pristine Pd/CeO2 exhibits a gradual slight increase of 1,3-butadiene conversion, but meanwhile undergoes a sharp decline of butenes selectivity at the temperature of 180 °C due to the high hydrogenation activity over mildly reduced Pd species. For Pd/CeO2-H300, as testified from CO-DRIFTS and XPS results, Pd nanoparticles dominate on the CeO2 surface and thus they show typically high hydrogenation activity but low butenes selectivity. Strikingly, with regard to Pd/CeO2-H600, where Pd nanoparticles are selectively encapsulated within the CeOx layer and only Pd single atoms act as active sites, 1,3-butadiene conversion increases from 31% to 100% at a reaction temperature of 100 °C. Meanwhile, the butenes selectivity remains as high as above 98%. Higher reduction temperature, such as 700 °C, can also render Pd SACs with high butenes selectivity [Supplementary Figure 9]. However, when the encapsulation layer retreats and Pd nanoparticles re-expose to the catalytic environment, the Pd/CeO2-H600-O500 again exhibits high hydrogenation activity, but the butenes selectivity dramatically drops to below 50%. In addition, to rule out the influence of oxidation state of Pd/CeO2-H600-O500 on the catalytic performance, this sample was further treated under reductive atmosphere at 300 °C. The as-obtained Pd/CeO2-H600-O500-H300 gives no palpable differences of activity and selectivity [Supplementary Figure 10], thus explicitly validating that the selective encapsulation of Pd nanoparticles is the necessary prerequisite for greatly improving butenes selectivity. Due to the weak interaction between Pd single atoms and adsorbents, such as CO, the exact exposed number of Pd single atoms cannot be quantified via the titration method

Figure 4. Catalytic performance of selective 1,3-butadiene hydrogenation over the series of Pd/CeO2 catalysts. (A) 1,3-butadiene conversion, (B) butenes selectivity as a function of reaction temperature, durability tests over Pd/CeO2-H600 at 110 °C with WHSV of (C) 60,000 and (D)120,000 mL/gcat/h. Reaction conditions: 2 vol.% 1,3-butadiene, 6 vol.% H2, He balanced. WHSV: Weight hourly space velocity.

Furthermore, the durability tests over Pd/CeO2-H600 were also conducted at 110 °C to examine the possible applications. As shown in Figure 4C, the 1,3-butadiene conversion is almost steady at 99% and butenes selectivity keeps above 97.5% during the time on stream of 60 h at the WHSV of 60,000 mL/gcat/h. In comparison with other catalytic results in literature, our Pd/CeO2-H600 still displays advantages considering 1,3-butadiene conversion, butenes selectivity and stability together [Supplementary Table 1]. Afterwards, this inspires us to test the catalytic stability in a more vigorous condition of higher WHSV of

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we developed selective encapsulation strategy to successfully synthesize Pd SACs by employing SMSI. Various characterizations demonstrate that Pd nanoparticles are more prone to be encapsulated within CeOx overlayer while Pd single atoms remain exposed under reductive atmosphere of 600 °C. The as-obtained Pd/CeO2-H600 exhibits 1,3-butadiene conversion of nearly 100% and meanwhile, the butenes selectivity remains as high as above 98% at the reaction temperature of 100 °C. Moreover, it also gives almost steady 1,3-butadiene conversion above 99% and keeps butenes selectivity higher than 97.5% for 60 h at the WHSV of 60,000 mL/gcat/h. This work illustrates the effectiveness of this selective encapsulation strategy to construct Pd SACs and can probably provide a prospective avenue to prepare various SACs for selective hydrogenation processes.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Writing - original draft, visualization, validation, supervision, methodology, investigation, data curation: Gao, Y.; Hu, W.

Writing - review and editing, visualization, validation, supervision, methodology, investigation, data curation, conceptualization: Liu, C.

Investigation, validation: Hong, F.

Writing - review and editing, visualization, validation, supervision, resources, investigation, conceptualization: Qiao, B.

Availability of data and materials

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1500503), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21961142006, 22388102, U23A20110, 22402192), and the CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (YSBR-022).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Martino, G.; Juguin, B.; Boitiaux, J. P. Catalysts and processes for C4’s cuts upgrading. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 1989, 44, 167-74.

3. Chada, J. P.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, D.; et al. Oligomerization of 1-butene over carbon-supported CoOx and subsequent isomerization/hydroformylation to n-nonanal. Catal. Commun. 2018, 114, 93-7.

4. Françoisse, O.; Thyrion, F. Kinetics and mechanism of ethyl tert-butyl ether liquid-phase synthesis. Chem. Eng. Process. Process. Intensif. 1991, 30, 141-9.

5. Wang, Z.; Santander, de. Soto. L.; Méthivier, C.; Casale, S.; Louis, C.; Delannoy, L. A selective and stable Fe/TiO2 catalyst for selective hydrogenation of butadiene in alkene-rich stream. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 7031-4.

6. Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Mou, X.; Lin, R.; Ding, Y. Design strategies and structure-performance relationships of heterogeneous catalysts for selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene. Chin. J. Catal. 2022, 43, 1017-41.

7. Pattamakomsan, K.; Suriye, K.; Dokjampa, S.; Mongkolsiri, N.; Praserthdam, P.; Panpranot, J. Effect of mixed Al2O3 structure between θ- and α-Al2O3 on the properties of Pd/Al2O3 in the selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene. Catal. Commun. 2010, 11, 311-6.

8. Pattamakomsan, K.; Ehret, E.; Morfin, F.; et al. Selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene over Pd and Pd–Sn catalysts supported on different phases of alumina. Catal. Today. 2011, 164, 28-33.

9. Hou, R.; Porosoff, M. D.; Chen, J. G.; Wang, T. Effect of oxide supports on Pd–Ni bimetallic catalysts for 1,3-butadiene hydrogenation. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 2015, 490, 17-23.

10. Kolli, N. E.; Delannoy, L.; Louis, C. Bimetallic Au–Pd catalysts for selective hydrogenation of butadiene: influence of the preparation method on catalytic properties. J. Catal. 2013, 297, 79-92.

11. Yi, H.; Xia, Y.; Yan, H.; Lu, J. Coating Pd/Al2O3 catalysts with FeOx enhances both activity and selectivity in 1,3-butadiene hydrogenation. Chin. J. Catal. 2017, 38, 1581-7.

12. Qiao, B.; Wang, A.; Yang, X.; et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 634-41.

13. Wang, A.; Li, J.; Zhang, T. Heterogeneous single-atom catalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2018, 2, 65-81.

14. Liu, L.; Corma, A. Metal catalysts for heterogeneous catalysis: from single atoms to nanoclusters and nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4981-5079.

16. Yan, H.; Cheng, H.; Yi, H.; et al. Single-atom Pd1/graphene catalyst achieved by atomic layer deposition: remarkable performance in selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 10484-7.

17. Yan, H.; Lv, H.; Yi, H.; et al. Understanding the underlying mechanism of improved selectivity in pd1 single-atom catalyzed hydrogenation reaction. J. Catal. 2018, 366, 70-9.

18. Huang, X.; Yan, H.; Huang, L.; et al. Toward understanding of the support effect on Pd1 single-atom-catalyzed hydrogenation reactions. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019, 123, 7922-30.

19. Xiong, H.; Datye, A. K.; Wang, Y. Thermally stable single-atom heterogeneous catalysts. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2004319.

20. Liu, S.; Li, J.; Xiong, H. Thermally-stable single-atom catalysts and beyond: a perspective. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 959525.

21. Qin, R.; Zhou, L.; Liu, P.; et al. Alkali ions secure hydrides for catalytic hydrogenation. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 703-9.

22. Jones, J.; Xiong, H.; DeLaRiva, A. T.; et al. Thermally stable single-atom platinum-on-ceria catalysts via atom trapping. Science 2016, 353, 150-4.

23. Wang, Y. R.; Zhuang, Q.; Cao, R.; et al. Reduction-controlled atomic migration for single atom alloy library. Nano. Lett. 2022, 22, 4232-9.

24. Hou, Z.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. A general dual-metal nanocrystal dissociation strategy to generate robust high-temperature-stable alumina-supported single-atom catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 15869-78.

25. Lv, H.; Guo, W.; Chen, M.; Zhou, H.; Wu, Y. Rational construction of thermally stable single atom catalysts: from atomic structure to practical applications. Chin. J. Catal. 2022, 43, 71-91.

26. Hai, X.; Xi, S.; Mitchell, S.; et al. Scalable two-step annealing method for preparing ultra-high-density single-atom catalyst libraries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2022, 17, 174-81.

27. Xie, F.; Cui, X.; Zhi, X.; et al. A general approach to 3D-printed single-atom catalysts. Nat. Synth. 2023, 2, 129-39.

28. Tauster, S. J.; Fung, S. C.; Garten, R. L. Strong metal-support interactions. Group 8 noble metals supported on titanium dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 170-5.

29. Tauster, S. J.; Fung, S. C.; Baker, R. T.; Horsley, J. A. Strong interactions in supported-metal catalysts. Science 1981, 211, 1121-5.

30. Hu, P.; Huang, Z.; Amghouz, Z.; et al. Electronic metal-support interactions in single-atom catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 3418-21.

31. Liu, X.; Liu, M. H.; Luo, Y. C.; et al. Strong metal-support interactions between gold nanoparticles and ZnO nanorods in CO oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 10251-8.

32. Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Lin, D.; et al. Strong metal–support interactions on gold nanoparticle catalysts achieved through Le Chatelier’s principle. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 418-24.

33. Dong, J.; Fu, Q.; Li, H.; et al. Reaction-induced strong metal-support interactions between metals and inert boron nitride nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 17167-74.

34. Yu, J.; Chen, W.; He, F.; Song, W.; Cao, C. Electronic oxide-support strong interactions in the graphdiyne-supported cuprous oxide nanocluster catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 1803-10.

35. Wu, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Oxidative-atmosphere-induced strong metal-support interaction and its catalytic application. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023, 56, 911-23.

36. Nakayama, A.; Sodenaga, R.; Gangarajula, Y.; et al. Enhancement effect of strong metal-support interaction (SMSI) on the catalytic activity of substituted-hydroxyapatite supported Au clusters. J. Catal. 2022, 410, 194-205.

37. Liu, X.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Atomically thick oxide overcoating stimulates low-temperature reactive metal-support interactions for enhanced catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 6702-9.

38. Pu, T.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, M. Engineering heterogeneous catalysis with strong metal-support interactions: characterization, theory and manipulation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202212278.

39. Ro, I.; Resasco, J.; Christopher, P. Approaches for understanding and controlling interfacial effects in oxide-supported metal catalysts. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 7368-87.

40. Han, B.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Y.; et al. Strong metal-support interactions between Pt single atoms and TiO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 11824-9.

41. Guo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, B.; et al. Photo-thermo semi-hydrogenation of acetylene on Pd1/TiO2 single-atom catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2648.

42. Bernal, S.; Calvino, J.; Cauqui, M.; et al. Some contributions of electron microscopy to the characterisation of the strong metal–support interaction effect. Catal. Today. 2003, 77, 385-406.

43. Zhang, S.; Plessow, P. N.; Willis, J. J.; et al. Dynamical observation and detailed description of catalysts under strong metal-support interaction. Nano. Lett. 2016, 16, 4528-34.

44. Jeong, H.; Bae, J.; Han, J. W.; Lee, H. Promoting effects of hydrothermal treatment on the activity and durability of Pd/CeO2 catalysts for CO oxidation. ACS. Catal. 2017, 7, 7097-105.

45. Xin, P.; Li, J.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Revealing the active species for aerobic alcohol oxidation by using uniform supported palladium catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 130, 4732-6.

46. Gulyaev, R.; Stadnichenko, A.; Slavinskaya, E.; Ivanova, A.; Koscheev, S.; Boronin, A. In situ preparation and investigation of Pd/CeO2 catalysts for the low-temperature oxidation of CO. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 2012, 439-40, 41-50.

47. Boronin, A.; Slavinskaya, E.; Danilova, I.; et al. Investigation of palladium interaction with cerium oxide and its state in catalysts for low-temperature CO oxidation. Catal. Today. 2009, 144, 201-11.

48. Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Qu, W.; et al. Well-defined palladium-ceria interfacial electronic effects trigger CO oxidation. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 10140-3.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].