Perspective on MOFs-derived catalysts for photothermal dry reforming of methane

Abstract

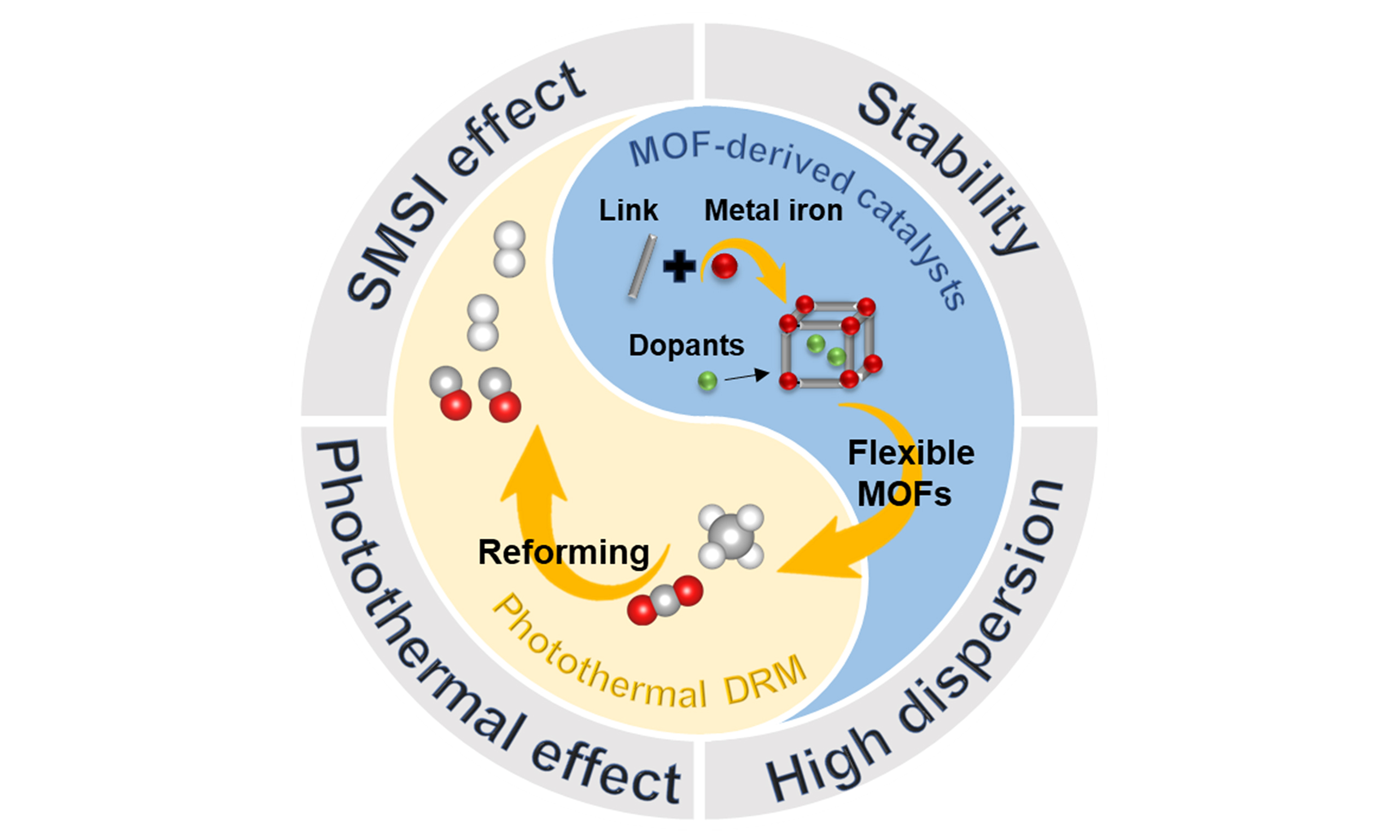

In the context of the global energy crisis and the urgent need for clean energy, dry reforming of methane (DRM) presents a dual benefit by transforming methane and CO2 into syngas with an ideal H2/CO ratio. However, traditional thermal DRM processes suffer from the need for elevated temperatures, a challenge that results in catalyst degradation and excessive carbon release. Photothermal catalysis has emerged as a viable alternative, effectively mitigating energy demand and reducing operational temperatures. Compared to traditional precious metal catalysts, non-precious metal catalysts, including Ni and Co, exhibit distinct benefits in terms of cost-effectiveness and availability. Despite these benefits, the rapid deactivation caused by carbon deposition and/or active metal sintering remains a major challenge for large-scale applications. Metal-organic framework (MOF)-derived catalysts have been considered an effective strategy to improve the dispersion and activity of Ni-based catalysts. Nonetheless, the development of MOFs is still in the nascent stages. This work offers a detailed review of progress in photothermal DRM catalyst development, highlighting the potential applications, key challenges, and systematic design principles for MOFs. Finally, we present a vision for the advancement of high-performance photothermal DRM catalysts, outlining key opportunities and challenges.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The world is presently grappling with a profound global energy crisis. Despite the rapid development of sustainable energy technologies, approximately 78% of the world’s primary energy demand still remains dependent upon fossil fuels such as oil, natural gas, and coal. When these fuels are combusted, large volumes of carbon dioxide (CO2) are emitted into the atmosphere. This emission is a key contributor to the greenhouse effect and the ongoing global climate change. Therefore, a transition from traditional energy systems to clean and renewable energy sources is not just desirable but imperative. In the course of the energy transition, natural gas, with methane (CH4) accounting for 90% of its composition, assumes a crucial role as an intermediate energy source. This is attributable to its vast reserves, relatively clean-burning characteristics, high chemical energy capacity, and the potential for synergistically using CO2[1,2]. Among the approaches to harnessing CH4 and CO2, dry reforming of methane (DRM) emerges as an efficient method. It not only absorbs CO2 but also produces syngas with an optimal H2/CO ratio of 1, which serves as a vital feedstock for industrial procedures such as Fischer-Tropsch synthesis.

Traditional thermally-catalytic DRM demands exceedingly high temperatures (in excess of 700 °C), resulting in increased carbon emissions and catalyst sintering, deactivation, and carbon deposition from CH4 decomposition, which further hinder efficiency and sustainability. Applying photocatalysis to DRM could theoretically reduce energy demands. Nevertheless, photocatalysis suffers from slow reaction rates, low photoconversion efficiency and poor selectivity for target products, making industrial implementation difficult. Photothermal catalysis is a prospective field. Compared with traditional techniques and photocatalysis, it exhibits competitive performance and energy-efficient characteristics, which makes it fit for large-scale implementation[3,4]. However, photothermal catalysis remains in nascent stages, with current catalyst design strategies constrained by limited innovation and unresolved challenges[5,6]. From this perspective, we center on the benefits and latest progressions of metal-organic framework (MOF)-derived catalyst materials in the course of the photothermal reaction for DRM (PDRM). The MOF-derived catalysts are featured with defective carbon layers, high surface area, and strong metal-support interactions (SMSI), which confer benefits on the PDRM reaction[7,8]. Nevertheless, these materials are currently at the nascent stage of DRM research. Thus, a forward-looking perspective on the development and rational design of photothermal catalysts for DRM is both necessary and timely. Such an approach would provide a roadmap for overcoming current limitations and driving the next wave of sustainable energy technologies.

CATALYSTS DEVELOPED FOR PHOTOTHERMAL DRM

To scale up photothermal catalysis for DRM applications, a key priority is developing catalysts with maximized efficiency, durability, and scalability, explicitly designed to operate with precision in large-scale, high-throughput environments. Catalytic active metals are broadly classified into precious metals (e.g., Pt, Ru, Rh) and non-noble metals (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni). While precious metals exhibit excellent resistance to coke deposition, their industrial implementation is hindered by scarcity and high cost[9]. Among transition metals, Ni-based catalysts have been the most extensively studied owing to their plentiful availability, low expense, and remarkable catalytic activity[10]. However, these materials face a critical challenge: deactivation resulting from coke deposition and metal agglomeration during the reaction. Therefore, to maximize the advantage of these active metals, researchers have developed various combinations of hybrid materials, including metal-semiconductor composites, bimetallic compounds (such as Ni-Pd, Ni-Ru, and Ni-Co) and metal-carbon catalysts[11,12]. Metal oxide semiconductors have long been recognized for their excellent CO2 adsorption and activation capabilities. However, effective C-H activation can only be achieved after modifying the catalysts with noble metals such as Pt, Pd and Ir, which creates a trade-off between catalyst preparation costs and overall efficiency[13]. Moreover, while non-noble metal catalysts (such as Co, Ni, and their alloys) have also been employed in PDRM, their lower intrinsic activity typically necessitates higher metal loadings. Combined with issues such as poor metal dispersion and sintering, this often results in incomplete utilization of the active metal within the system. Therefore, developing materials that simultaneously offer high catalytic activity, long durability, and low operating temperatures remains a significant challenge. The recent exemplary studies regarding the PDRM reaction are presented in Table 1.

Representative research regarding the PDRM reaction

| No. | Sample | Feed gas | Conditions | Production rates | Ref. |

| 1 | Pt/black TiO2 | CO2/CH4 = 1/1, GHSV = 40,000 mL/g/h | 300 W Xe, 550 °C | H2 = 95 mmol·h-1·g-1, CO = 191 mmol·h-1·g-1 | [14] |

| 2 | Pt/TaN | CO2/CH4 = 1/1, GHSV = 12,000 mL/g/h | 300 W Xe, 0.42 W·cm-2, 550 °C | H2 = 1,100 mmol·g-1·min-1, CO = 1,200 mmol·g-1·min-1 | [15] |

| 3 | Pt/Si–CeO2 | CO2/CH4/Ar = 1/1/8, 14 sccm | 1,200 W, 30 suns, 600 °C | H2 = 90 mmol·h-1·gcat-1, CO = 154 mmol·h-1·gcat-1 | [16] |

| 4 | Cu-CNN/Pd-BDCNN | CO2/CH4 =1/1 GHSV = 30,000 mL/g/h | 300 W Xe, 25 °C | H2 = 0.8 mmol·h-1·gcat-1, CO = 0.8 mmol·h-1·gcat-1 | [17] |

| 5 | Pt/TiO2 (P25) | CO2/CH4/Ar = 48/48/4, GHSV = 60,000 mL/g/h | 300 W Xe, 700 °C | H2 = 600 mmol·h-1·gcat-1, CO = 750 mmol·h-1·gcat-1 | [3] |

| 6 | 1 wt% Rh/LaNiO3 | CO2/CH4/Ar = 2/2/6, GHSV = 60,000 mL/g/h | 300 W Xe, 550 °C | H2 = 452.3 mmol·h-1·gRh-1, CO = 527.6 mmol·h-1·gRh-1 | [18] |

| 7 | Ru/SrTiO3 | CO2/CH4/N2 = 36/36/28, GHSV = 18,000 mL/g/h | 300 W Xe, 600 °C | H2 = 325 mmol·h-1·g-1, CO = 380 mmol·h-1·g-1 | [9] |

| 8 | 25 wt% Ni/SiO2 | CO2/CH4/N2/Ar = 12.5/10/5/72.5, GHSV = 18,000 mL/g/h | 300 W Xe, 452 °C | H2 = 12.6 mmol·h-1, CO = 7.45 mmol·h-1 | [19] |

| 9 | Ni(SA)/CeO2 | CO2/CH4/N2 = 1/1/3, GHSV = 48,000 mL/g/h | 300 W Xe, 472 °C | H2 = 8.56 mol·molNi-1·min-1, CO = 7.68 mol·molNi-1·min-1 | [20] |

| 10 | Ru/TiO2-H2 | CO2/CH4//N2 = 8/8/84, GHSV = 600,000 mL/g/h | 12.0 W·cm-2, 550 °C | H2 = 1,600 mmol·h-1·g-1, CO = 1,400 mmol·h-1·g-1 | [21] |

| 11 | Ni/CeO2 | CO2/CH4/N2 = 1/1/8, 120.5 mL/min | 500 W Xe, 36.34 W·cm-2, 807 °C | H2 = 326.5 μmol·min-1, CO = 313.5 μmol·min-1 | [22] |

| 12 | 10Ni/Al2O3 | CH4/CO2 = 1:1, 20.0 mL/min | 1.07 W·cm-2, 550 °C | H2 = 6.25 μmol·min-1, CO = 6.5 μmol·min-1 | [23] |

| 13 | SCM-Ni/SiO2 | CO2/CH4/N2 = 11.7/11.5/76.8, GHSV = 29.308 mL/g/h | 500 W Xe, 34.36 W·cm-2, 646 °C | H2 = 415.5 μmol·min-1, CO = 483.6 μmol·min-1 | [24] |

| 14 | Co/Al2O3 | CO2/CH4/N2 = 3/3/4, GHSV = 267.600 mL/g/h | 500 W Xe, 35.39 W·cm-2, 588 °C | H2 = 628.4 μmol·min-1, CO = 759.4 μmol·min-1 | [25] |

| 15 | Pt/CeO2 | CO2/CH4/N2 = 1/1/8, GHSV = 168,000 mL/g/h | 1,200 W | H2 = 290 μmol·h-1, CO = 900 μmol·h-1 | [26] |

| 16 | Ni@SiO | 30 mg Ni, 20.0 mL/min, CH4/CO2 = 1/1 | 1.07 W·cm-2, 550 °C | H2 = 37.5 μmol·h-1, CO = 41.4 μmol·h-1 | [27] |

| 17 | Ni@SiO2-core | 30 mg Ni, 20.0 mL/min, CH4/CO2 = 1/1 | 1.07 W·cm-2, 550 °C | H2 = 19.5 μmol·h-1, CO = 23.4 μmol·h-1 | [27] |

| 18 | Ni-CeO2/SiO2 | CO2/CH4/Ar = 3/3/4, GHSV = 220.560 mL/g/h | 38.52 W·cm-2, 678 °C | H2 = 33.42 mmol·min-1·g-1, CO = 41.53 mmol·min-1·g-1 | [28] |

| 19 | Ni/Ni-Al2O3 | CO2/CH4/Ar = 19.4/19.3/ 61.3, GHSV = 271.800 mL/g/h | 33.38 W·cm-2, 771 °C | H2 = 27.02 mmol·min-1·g-1, CO = 28.71 mmol·min-1·g-1 | [29] |

| 20 | Ni/Ga2O3 | CH4/CO2 = 1, GHSV = 40,000 mL/g/h | 2.7 W·cm-2, 391 °C | H2 = 200 μmol·min-1·g-1, CO = 210 μmol·min-1·g-1 | [30] |

To develop highly efficient catalysts for the DRM reaction, understanding the PDRM mechanism is essential. This mechanism classifies PDRM into two modes: thermal-assisted photocatalytic DRM and photo-driven thermo-catalytic DRM, considering the individual contributions of light and heat energy. In thermal-assisted photocatalytic DRM[31,32], heat lowers the activation energy of photocatalysis, accelerates the migration of photogenerated carriers and reactants and enhances molecule adsorption and diffusion on the catalyst surface. This reduces carrier recombination and boosts catalytic performance. In contrast, photo-driven thermos-catalytic DRM[33,34] relies on photothermal conversion and the plasma effect. Photothermal conversion heats the catalyst surface, while the plasma effect generates hot electrons that activate reactants and lower the reaction activation energy. Based on these mechanisms, targeted catalyst modifications can improve PDRM. For thermal assisted photocatalytic DRM, enhancing light absorption and carrier separation is key, and for photo-driven thermos-catalytic DRM, improving photothermal conversion and suppressing carbon deposition are crucial.

MOFS-DERIVED CATALYSTS FOR PHOTOTHERMAL DRM

Utilizing MOFs as surface catalyst templates is a relatively fresh technique for the synthesis of catalysts with remarkable stability. MOFs are made up of clearly defined porous nanostructures. The nanostructures are formed from core metal ions or clusters linked together by organic linkers, thus making MOFs ideal for synthesizing highly dispersed nanoporous catalysts. Besides, the photothermal effect plays a crucial role in PDRM reactions. Carbonaceous and organic materials manifest a photothermal effect strongly reliant on the p → p* orbital transition, which demands lower energy input compared to other electronic transitions[35,36]. This phenomenon provides theoretical support for achieving efficient PDRM at lower temperatures.

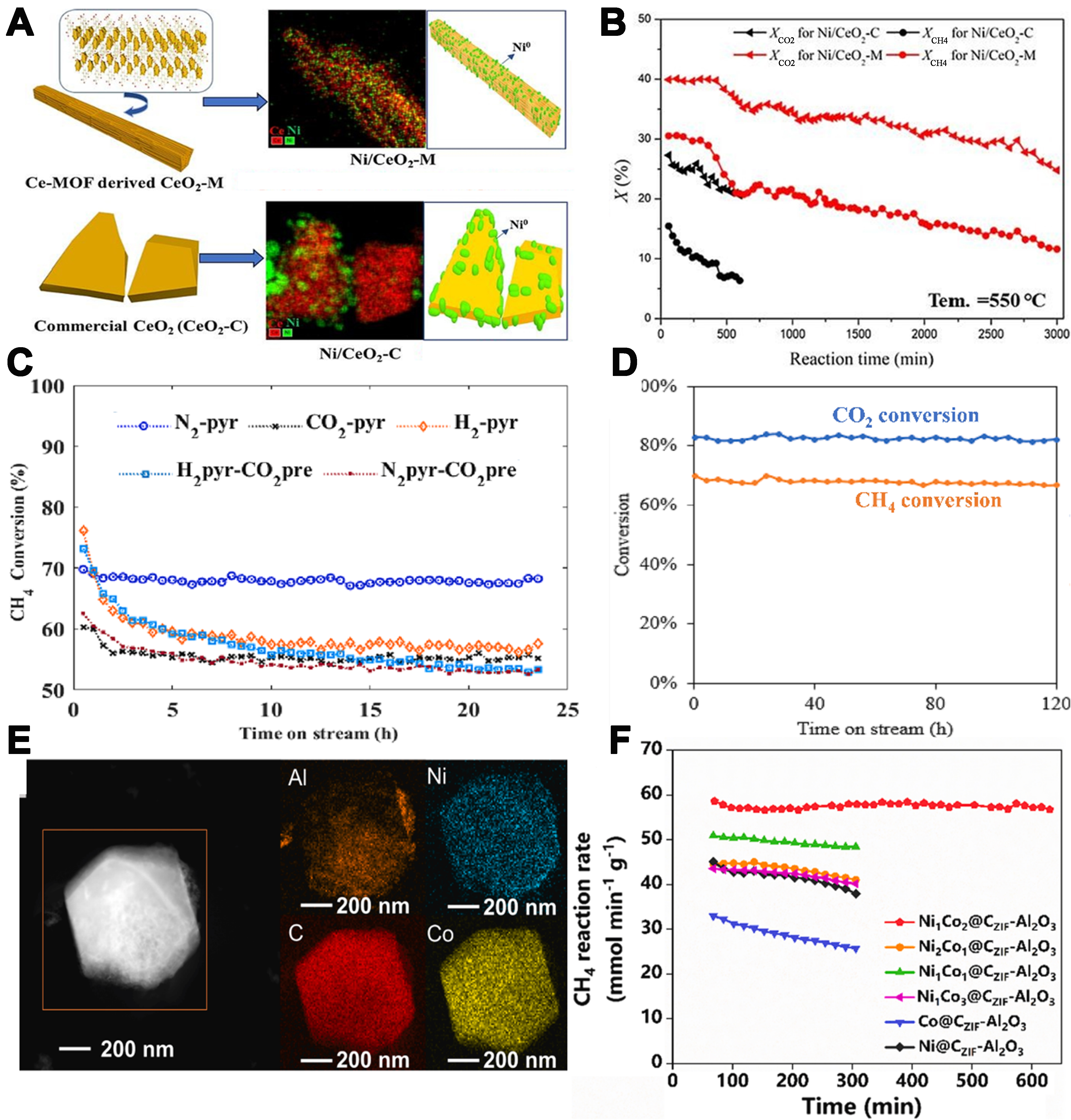

Consequently, MOF-derived catalysts have caught much attention due to their prospects in DRM catalyst development, as depicted in Figure 1. For instance, the Ni/CeO2-M catalysts derived from the bimetallic Ni-Ce-MOF template have better DRM activity and are more resistant to carbon deposition and sintering compared to the Ni/CeO2-C catalyst made by the impregnation method[37]. Studies on catalyst deactivation show that the resistance to sintering comes from the intense metal-support interaction between uniformly dispersed Ni and CeO2-M. Compared with Ni/CeO2-C, the MOF-derived Ni/CeO2-M catalyst has better resistance to carbon deposition, probably because of its plentiful oxygen vacancies. These vacancies prompt the formation of active oxygen species that can get rid of carbon deposits. Different thermal treatment conditions in N2, H2, or CO2 atmospheres were employed to remove the organic template. Studies indicated that pyrolysis in CO2 produced a catalyst with a larger crystallite size (10.76 nm), mainly because of the oxidation of metallic Ni, which facilitates the generation of bulkier metal-oxide species. In comparison, pyrolysis with N2 gas could obtain the smallest crystallite size of Ni0 (2.19 nm), largest Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface and Ni0 proportion, which are beneficial to the DRM reaction. The optimized Ni/CeO2-MOF catalyst shows excellent stability, with no significant loss in activity after 120 h of continuous operation. This is because the MOF template facilitates high metallic nickel and Ce3+ content, and SMSI between Ni and Ce and provides a high surface area[15]. Similarly, Ni-Co bimetallic catalysts synthesized via MOF-derived methods not only significantly reduced carbon deposition due to synergistic effects between Ni and Co but also achieved high selectivity for CH4 and CO2 conversion, yielding an H2/CO ratio close to the ideal value[8,38].

Figure 1. (A) the high dispersion of Ni on Ni/CeO2-MOF; (B) Ni/CeO2-MOF shows higher conversion and stability than Ni/CeO2-C; (C) Pyrolysis condition on the DRM activity of MOF-derived catalysts; (D) High stability of Ni/CeO2-MOF during DRM; (E) The high dispersion of Ni and Co on Ni1Co2-ZIF/Al2O3; (F) The influence of Ni and Co atom ratio on the DRM activity of MOF-derived catalysts. [(A and B) are reproduced with permission from ref.[37], Copyright 2024, Elsevier. (C and D) are reproduced with permission from ref.[39], Copyright 2023, Elsevier. (E and F) are reproduced with permission from ref.[8], Copyright 2024, Elsevier.] MOF: Metal-organic framework; DRM: methane dry reforming.

However, despite the considerable potential of MOF-derived catalysts in the PDRM field, their application remains in the exploratory stage. The diverse range of MOF materials, varied synthesis methods, and flexible tunability of atomic ratios and ligand structures offer opportunities for the precise design of catalytic active sites, yet they also pose challenges in efficiently screening and optimizing catalyst structures. Achieving precise template removal under different reaction atmospheres and further enhancing the interactions between the metal and support remain key issues to be addressed in future research.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVE

This perspective review presents a comprehensive and clear introduction to PDRM catalysts, offering a systematic classification and discussing the challenges in developing different catalyst types. This analysis thereby establishes a solid foundation for both fundamental understanding and advancements in applied technology. Among these, MOF-derived catalysts emerge as a promising frontier in creating efficient and stable systems for PDRM, due to their unique structural characteristics and excellent photothermal effect. Nonetheless, several critical challenges must be addressed before these catalysts can be fully deployed in industrial applications. Catalytic activity and selectivity are hampered by insufficient active sites. During MOF synthesis, structural changes can damage or block potential active sites. High-temperature treatment, for example, may collapse the MOF structure, reducing metal center accessibility. However, future development directions are promising. Advanced synthesis strategies include controlled growth methods such as templating for MOF growth and atomic layer deposition for precise coating. Tailoring catalyst properties involves designing active sites by modifying MOF metal center coordination to boost activity and selectivity, and enhancing stability using thermally stable precursors. To improve light harvesting, introducing light-absorbing moieties or creating heterostructures can broaden absorption. Computational methods can optimize energy transfer. For cost-effectiveness, using low-cost precursors from waste or renewable resources and developing scalable production, such as continuous-flow synthesis, are feasible.

Addressing these challenges will not only advance the practical implementation of PDRM but also contribute to broader sustainable energy initiatives, ultimately facilitating the global shift toward more sustainable and efficient energy infrastructures.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Eastern Institute of Technology, Ningbo.

Authors’ contributions

Manuscript preparation: Pan, T.; Zhao, H.

Manuscript correction: Ma, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, H.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work is financially supported by Eastern Institute of Technology, Ningbo. We also acknowledge support by the Young Innovative Talent of Yongjiang Talent Project (2023A-387-G).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Tavasoli, A.; Gouda, A.; Zähringer, T.; et al. Enhanced hybrid photocatalytic dry reforming using a phosphated Ni-CeO2 nanorod heterostructure. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1435.

2. Wang, Z.; Lv, Q.; Li, A.; et al. Reveal and correlate working geometry and surface chemistry of Ni nanocatalysts in CO2 reforming of methane. Mater. Today. 2024, 79, 16-27.

3. Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; et al. The nature of active sites for plasmon-mediated photothermal catalysis and heat-coupled photocatalysis in dry reforming of methane. Energy. Environ. Mater. 2023, 6, e12416.

4. Yu, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Gates, I. D.; Hu, J. Photothermal catalytic H2 production over hierarchical porous CaTiO3 with plasmonic gold nanoparticles. Chem. Synth. 2023, 3, 3.

5. Zhou, L.; Swearer, D. F.; Zhang, C.; et al. Quantifying hot carrier and thermal contributions in plasmonic photocatalysis. Science 2018, 362, 69-72.

6. Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Duan, X.; Sun, H.; Wang, S. Photothermal catalysis: from fundamentals to practical applications. Mater. Today. 2023, 68, 234-53.

7. Vakili, R.; Gholami, R.; Stere, C. E.; et al. Plasma-assisted catalytic dry reforming of methane (DRM) over metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)-based catalysts. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2020, 260, 118195.

8. Liu, X.; Mu, Z.; Sun, C.; et al. Highly efficient solar-driven CO2-to-fuel conversion assisted by CH4 over NiCo-ZIF derived catalysts. Fuel 2022, 310, 122441.

9. Tang, Y.; Li, Y.; Bao, W.; et al. Enhanced dry reforming of CO2 and CH4 on photothermal catalyst Ru/SrTiO3. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2023, 338, 123054.

10. Zhou, Z.; Sarmad, S.; Huang, C.; Deng, G.; Sun, Z.; Duan, L. Ni-based catalyst supported on ordered mesoporous Al2O3 for dry CH4 reforming: effect of the pore structure. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2024, 52, 275-88.

11. Huang, L.; Li, D.; Tian, D.; et al. Optimization of Ni-based catalysts for dry reforming of methane via alloy design: a review. Energy. Fuels. 2022, 36, 5102-51.

12. Truong-Phuoc, L.; Essyed, A.; Pham, X.; et al. Catalytic methane decomposition process on carbon-based catalyst under contactless induction heating. Chem. Synth. 2024, 4, 56.

13. Zhang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Yu, X.; et al. Photo-thermal coupled single-atom catalysis boosting dry reforming of methane beyond thermodynamic limits over high equivalent flow. Nano. Energy. 2024, 123, 109401.

14. Zhou, L.; Martirez, J. M. P.; Finzel, J.; et al. Light-driven methane dry reforming with single atomic site antenna-reactor plasmonic photocatalysts. Nat. Energy. 2020, 5, 61-70.

15. Liu, H.; Song, H.; Zhou, W.; Meng, X.; Ye, J. A promising application of optical hexagonal TaN in photocatalytic reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 16781-4.

16. Pan, F.; Xiang, X.; Deng, W.; Zhao, H.; Feng, X.; Li, Y. A novel photo-thermochemical approach for enhanced carbon dioxide reforming of methane. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 940-5.

17. Zhou, W.; Wang, B.; Tang, L.; et al. Photocatalytic dry reforming of methane enhanced by “dual-path” strategy with excellent low-temperature catalytic performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2214068.

18. Yao, Y.; Li, B.; Gao, X.; et al. Highly efficient solar-driven dry reforming of methane on a Rh/LaNiO3 catalyst through a light-induced metal-to-metal charge transfer process. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2303654.

19. Takami, D.; Tsubakimoto, J.; Sarwana, W.; Yamamoto, A.; Yoshida, H. Photothermal dry reforming of methane over phyllosilicate-derived silica-supported nickel catalysts. ACS. Appl. Energy. Mater. 2023, 6, 7627-35.

20. Rao, Z.; Wang, K.; Cao, Y.; et al. Light-reinforced key intermediate for anticoking to boost highly durable methane dry reforming over single atom Ni active sites on CeO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 24625-35.

21. Li, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, G.; Chen, J.; Jia, H. Suppressive strong metal-support interactions on ruthenium/TiO2 promote light-driven photothermal CO2 reduction with methane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202300129.

22. Zhang, Q.; Mao, M.; Li, Y.; et al. Novel photoactivation promoted light-driven CO2 reduction by CH4 on Ni/CeO2 nanocomposite with high light-to-fuel efficiency and enhanced stability. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2018, 239, 555-64.

23. Liu, H.; Dao, T. D.; Liu, L.; Meng, X.; Nagao, T.; Ye, J. Light assisted CO2 reduction with methane over group VIII metals: universality of metal localized surface plasmon resonance in reactant activation. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2017, 209, 183-9.

24. Huang, H.; Mao, M.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Solar-light-driven CO2 reduction by CH4 on silica-cluster-modified Ni nanocrystals with a high solar-to-fuel efficiency and excellent durability. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2018, 8, 1702472.

25. Wu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; et al. High light-to-fuel efficiency and CO2 reduction rates achieved on a unique nanocomposite of Co/Co doped Al2O3 nanosheets with UV-vis-IR irradiation. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 2581-90.

26. Pan, F.; Xiang, X.; Du, Z.; Sarnello, E.; Li, T.; Li, Y. Integrating photocatalysis and thermocatalysis to enable efficient CO2 reforming of methane on Pt supported CeO2 with Zn doping and atomic layer deposited MgO overcoating. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2020, 260, 118189.

27. Liu, H.; Meng, X.; Dao, T. D.; et al. Light assisted CO2 reduction with methane over SiO2 encapsulated Ni nanocatalysts for boosted activity and stability. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2017, 5, 10567-73.

28. Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; et al. A novel nanocomposite of mesoporous silica supported Ni nanocrystals modified by ceria clusters with extremely high light-to-fuel efficiency for UV-vis-IR light-driven CO2 reduction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019, 7, 4881-92.

29. Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wu, S.; et al. UV-vis-IR irradiation driven CO2 reduction with high light-to-fuel efficiency on a unique nanocomposite of Ni nanoparticles loaded on Ni doped Al2O3 nanosheets. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019, 7, 19800-10.

30. Rao, Z.; Cao, Y.; Huang, Z.; et al. Insights into the nonthermal effects of light in dry reforming of methane to enhance the H2/CO ratio near unity over Ni/Ga2O3. ACS. Catal. 2021, 11, 4730-8.

31. Sun, M.; Zhao, B.; Chen, F.; et al. Thermally-assisted photocatalytic CO2 reduction to fuels. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 408, 127280.

32. Han, B.; Wei, W.; Chang, L.; Cheng, P.; Hu, Y. H. Efficient visible light photocatalytic CO2 reforming of CH4. ACS. Catal. 2016, 6, 494-7.

33. Liu, G.; Meng, X.; Zhang, H.; et al. Elemental boron for efficient carbon dioxide reduction under light irradiation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 5570-4.

34. Wang, S. J.; Su, D.; Zhang, T. Research progress of surface plasmons mediated photothermal effects. Acta. Phys. Sin. 2019, 68, 144401.

35. Wang, D.; Chen, R.; Zhu, X.; et al. Synergetic photo-thermo catalytic hydrogen production by carbon materials. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 1602-8.

36. Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; et al. Combined steam and CO2 reforming of methane over Co–Ce/AC-N catalyst: effect of preparation methods on catalyst activity and stability. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2022, 47, 2914-25.

37. Zhou, D.; Huang, H.; Cai, W.; Liang, W.; Xia, H.; Dang, C. Immobilization of Ni on MOF-derived CeO2 for promoting low-temperature dry reforming of methane. Fuel 2024, 363, 130998.

38. Liang, T. Y.; Senthil Raja, D.; Chin, K. C.; et al. Bimetallic metal-organic framework-derived hybrid nanostructures as high-performance catalysts for methane dry reforming. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020, 12, 15183-93.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].