Challenges of photocatalytic extraction of uranium: a review

Abstract

Nuclear energy, known for its low carbon emissions and high energy density, is considered one of the most promising future energy sources. However, the generation of nuclear waste and depletion of uranium resources make the development of simple, efficient, and cost-effective uranium extraction methods critical for the sustainable development of nuclear energy and environmental recovery. Photocatalytic uranium extraction, as a straightforward, highly efficient, and low-cost technique, has attracted increasing attention from researchers. Herein, we provide a comprehensive overview of the mechanisms behind photocatalytic uranium extraction, summarizing the evolution of materials used in this process. It also evaluates the experimental progress in extracting U(VI) from real uranium-containing wastewater and seawater. Moreover, the review highlights the challenges currently faced by photocatalytic uranium extraction technologies, such as the stability and scalability of photocatalysts, and discusses future development directions. Additionally, modification strategies to enhance the photocatalytic performance of catalysts are summarized, with comparisons drawn between the strengths and limitations of various materials used for U(VI) extraction. This review concludes with an evaluation of the potential of photocatalytic technologies for large-scale applications and their role in addressing environmental concerns related to uranium extraction.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Nuclear energy has attracted worldwide attention because of its energy output efficiency and extra low CO2 emission[1]. It plays a critical role in achieving CO2 emission reduction targets and advancing carbon neutrality initiatives. Uranium [U(VI)], the main element used in the production of nuclear fuel, is therefore crucial for the sustainable development of nuclear energy utilization[2]. Traditionally, U(VI) is extracted from uranium ore, a process that relies heavily on strong acids. This method not only contributes to severe environmental pollution but also generates large quantities of uranium tailings, leading to the release of U(VI) and other heavy metals into the surrounding environment[3]. More importantly, the global reserves of uranium ore are projected to sustain peaceful nuclear power generation for only about 60 more years[4]. In contrast, natural seawater contains approximately 4.5 billion tons of dissolved U(VI) at a concentration of ~3.3 ppb, and uranium tailing wastewater often exhibits even higher concentrations of U(VI)[5-7]. As a result, the efficient and selective extraction of U(VI) from seawater and wastewater has emerged as a major research focus, offering a promising alternative to traditional extraction methods.

Traditional uranium extraction methods, such as solvent extraction and sorption, have been utilized for decades[8]. However, solvent extraction often leads to the release of harmful chemicals, high energy consumption, and a significant carbon footprint. These techniques also struggle to recover uranium from low-concentration ores, making them inefficient and resource-intensive. Additionally, terrestrial uranium resources are relatively limited, with an estimated total of approximately 7.64 million tons, expected to meet human demand for only about 120 years. These limitations highlight the need for more sustainable and economically viable alternatives. For extraction uranium from seawater, Tamada used radiation-induced graft polymerization to fabricate 350 kg amidoxime adsorbent, and dipped at 7 km offing of Mutsu-Sekine seashore, the U(VI) adsorption capacity reached 1.5 g-U/kg-ad in 30 days soaking, and collected 1 kg yellow cake in total 9 tests over three years[9]. This proved that U(VI) extraction from seawater can be achieved. However, the selectivity, adsorption capacity, stability and reusability of the adsorbents should be considered. Other methods, including electrocatalysis (using electrochemical reactions to reduce and recover uranium) and membrane separation (which relies on selective permeability), are also considered viable alternatives[4,10]. Furthermore, other techniques such as ion exchange and piezoelectric catalysis have been proposed, each offering distinct advantages and limitations[11,12]. Notably, seawater and uranium-containing wastewater often contain not only radioactive nuclides but also a variety of soluble organic substances [such as citric acid, oxalic acid (OA), ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), tannic acid, and sulfonic acid], as well as coexisting ions. These factors significantly complicate the process of U(VI) extraction. Given the low solubility and low mobility of U(IV), reducing hexavalent uranium [U(VI)] to tetravalent uranium can facilitate efficient uranium fixation.

Inspired by the application of photocatalysis in H2 evolution, CO2 reduction, H2O2 production and environmental treatment[13-16], photocatalysis has emerged as a promising method for uranium removal, which is pollution-free and environment-friendly by using solar energy[2,17-20]. In the case of uranium extraction, photocatalysis can selectively extract uranium from aqueous solutions by utilizing light energy to activate the photocatalyst. The mechanism of photocatalytic uranium extraction generally involves the absorption of photons by the photocatalyst, leading to the generation of electron-hole pairs. These excited electrons and holes interact with water or other species in the solution, producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydroxyl radicals (·OH) and superoxide anions (·O2-). These reactive species can then reduce U(VI) to insoluble U(IV), facilitating its recovery from the solution. In 1991, Amadelli et al. first achieved the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI) using TiO2 as a photocatalyst[21]. Since then, research into photocatalytic uranium reduction has rapidly increased year by year. Compared to traditional methods, photocatalysis offers several advantages. It is an energy-efficient process that can be driven by sunlight or low-intensity ultraviolet (UV) light, making it more sustainable than methods that require high energy loss or chemical additives. Additionally, photocatalysis can be applied to low-concentration uranium solutions, where conventional methods often fall short. The selectivity of photocatalysis also minimizes the extraction of unwanted elements, reducing the environmental impact. Despite these advantages, challenges remain, such as the development of stable, high-performance photocatalysts and the need to improve reaction kinetics for large-scale applications.

Recent reports on the use of photocatalysis for uranium extraction have been steadily increasing. Therefore, it is necessary to review the latest progress in uranium extraction photocatalysts to provide insights for the design and development of more efficient materials for this purpose. This review focuses on the development of photocatalytic uranium extraction, discussing the strategies, principles and mechanisms employed by various photocatalysts under different conditions. Additionally, the review addresses the key challenges and future prospects for photocatalysts in solar energy utilization, suggesting potential research avenues and directions. This review is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the key role of photocatalysis in the development of uranium recovery technologies and to provide a valuable reference for the innovative applications of sustainable nuclear energy in the future.

FUNDAMENTALS OF PHOTOCATALYTIC URANIUM EXTRACTION

Principle of photocatalysis

Photocatalysis is a light-driven process in which a semiconductor catalyst, upon absorbing photons, facilitates a chemical reaction[22]. The process begins when the catalyst absorbs photons whose energy is greater than or equal to its bandgap energy (Eg)[23,24]. This excitation leads to the promotion of electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), leaving behind holes in the VB[25]. These electron-hole pairs are the fundamental carriers responsible for initiating redox reactions [Figure 1A]. The efficiency of the photocatalytic process depends on several key factors: the bandgap of the photocatalyst, its surface area, and its chemical stability under reaction conditions. The bandgap determines the energy threshold for the catalyst to absorb light, and semiconductors with narrow bandgaps can absorb a broader range of light, including visible light[23,24,26,27]. In uranium extraction, the photogenerated electrons reduce uranium ions [e.g., U(VI) to U(IV)], while the holes in the VB participate in oxidation reactions, such as oxidizing water to generate ROS[22,28]. Materials such as graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) and bismuth-based catalysts have shown particular promise in uranium extraction due to their ability to absorb visible light, unlike titanium dioxide (TiO2), which primarily absorbs UV light due to its wide bandgap (~3.2 eV)[29-32].

Figure 1. (A) The mechanism of photocatalytic stages: (1) light harvesting; (2) charge excitation; (3) charge separation; (4) charge recombination; (5) surface charge recombination; (6) reduction and (7) oxidation reaction; (B) Redox potential of U(VI) and common active species in photocatalytic; (C) Illustration of reaction mechanism with or without sacrificial reagent in uranium extraction.

Photocatalytic uranium extraction process

Based on the principles of photocatalysis, the occurrence of redox reactions is governed by the relative electrode potentials of the electron donor and acceptor species. Specifically, the electron donor must have an oxidation potential higher than the VB potential, while the electron acceptor must have a reduction potential lower than the CB potential of the catalyst. The relative positions of these potentials, as illustrated in [Figure 1B], determine the feasibility of redox reactions. In the case of uranium extraction, the reduction potential of U(VI) is a critical factor in facilitating its reduction under photocatalytic conditions.

Several pathways have been identified for the electron transfer during the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI)[33]:

(i). One-Electron Reduction: In this process, U(VI) is first reduced by a photogenerated electron to U(V), which can then be further reduced to U(IV). Notably, U(V) can undergo disproportionation, forming both U(VI) and U(IV) in the process. The reactions are as follows:

U(VI) + e- → U(V)

U(V) + e- → U(IV)

U(V) → U(VI) + (IV)

(ii). Two-Electron Reduction: Alternatively, U(VI) can be directly reduced to U(IV) via a two-electron transfer reaction, which is a more efficient pathway for uranium extraction:

U(VI) + 2e- → U(IV)

(iii). Reduction Under Acidic Conditions: Under acidic conditions, protons in the solution can participate in the two-electron reduction process, facilitating the reduction of U(VI) to U(IV). The reaction proceeds as follows:

UO22+ + 4H+ + 2e- → U4+ + 2H2O

(iv). Reduction by Superoxide Radicals (·O2-): In some systems, U(VI) can be reduced by superoxide radicals (·O2-), which are generated upon electron transfer to molecular oxygen[34,35]. The reactions proceed as:

O2 + e- → ·O-2

x·O2- + U6+ → U(6-X)+ + xO2

or 2·O2- + UO22+ → UO2 + 2O2

(v). In the multi-electron photocatalytic reaction, oxygen (O) undergoes two-electron transfer to generate H2O2. The chemical equation is as follows:

O2 + 2H+ + 2e- → H2O2

·O2- + e- + 2H+ → H2O2

CH3OH + ·OH/·O2- → CO2 + H2O

UO22+ + H2O2 + 2H2O → UO2(O2)·2H2O + 2H+

Under different pH conditions, uranyl can react with photogenerated H2O2 to form water-insoluble metastudtite [(UO2)O2·2H2O] [Figure 1C], or directly reduce to UO2 when sacrificial reagents are added, and methanol is oxidized to CO2 and H2O.

Additionally, when organic matter is present in the system, it can act as an electron donor, thus extending the lifetime of the photogenerated electrons and enhancing the reduction of U(VI)[36]. The role of organic species as electron donors is significant, as they can stabilize the photogenerated electrons, preventing their recombination and promoting more efficient uranium reduction. It is important to note that while these pathways are established, the mechanism of photocatalytic reduction of U(VI) remains an area of active research, and further investigation is required to fully elucidate the electron transfer dynamics and reaction intermediates involved in this process.

Chemical behavior of uranium

Uranium exists in several oxidation states in aqueous environments, with the most common being U(VI) and U(IV). In oxidizing environments, uranium typically exists as the uranyl ion (UO22+), which is soluble and highly mobile in water. The hexavalent form of uranium [U(VI)] is more prone to leaching and dissolution from mineral ores, which is why it is often the target of extraction methods. The redox behavior of uranium plays a crucial role in photocatalytic uranium extraction. Under light irradiation, photogenerated electrons reduce U(VI) to U(IV), which has significantly lower solubility and can be more easily extracted from the solution. The presence of various ligands, the pH of the solution, and the concentration of other reactive species, such as ·OH, also influence the redox behavior of uranium during photocatalysis. At lower pH values, uranium generally exists as UO22+, while at higher pH, uranium can form complex species such as UO2(OH)3- or UO2(OH)42-[22,37,38]. Under photocatalytic conditions, the redox equilibrium between these species can shift, with the photogenerated electrons promoting the reduction of UO2+. Additionally, the presence of competing ions, such as calcium (Ca2+), magnesium (Mg2+), or carbonate (CO32-), can also affect uranium redox behavior and the efficiency of the extraction process[39-43]. These ions may form precipitates with uranium or alter the reaction kinetics, thereby influencing the overall efficiency of uranium removal.

It is noteworthy that although significant progress has been made in understanding the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI), the exact mechanism remains incomplete and requires further investigation. For instance, Li et al. analyzed uranium species in the liquid phase using absorption spectroscopy[23]. During the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI) on TiO2, the characteristic absorption peak of U(VI) in the range of 350-500 nm rapidly decreased, indicating a reduction process. Upon treating the system with hydrochloric acid, the reduced uranium species deposited on the TiO2 surface dissolved, and the characteristic absorption peak of U(IV) appeared in the supernatant. This observation provided direct evidence for the formation of U(IV) on the surface of TiO2. However, the role of U(V) as an intermediate in this process remains unclear due to its tendency to undergo rapid disproportionation, which can result in the simultaneous formation of U(VI) and U(IV). In homogeneous photocatalytic systems, the presence of U(V) was confirmed through the detection of its characteristic electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signals[44]. Interestingly, as the irradiation time was extended, these signals gradually transitioned into a mixed signal of U(V) and U(IV), directly confirming the disproportionation of U(V) into other species. A similar phenomenon was observed in isopropanol-based homogeneous photocatalytic systems, further supporting the potential involvement of U(V) as a transient intermediate[45]. In contrast, no soluble lower-valent uranium species [e.g., U(V), U(IV), or U(III)] were detected in heterogeneous systems involving TiO2[45]. This raises questions about the nature of uranium intermediates in such systems. One possibility is that U(V) forms momentarily but undergoes rapid disproportionation, making it undetectable. Another explanation is that U(V) may not form at all in certain heterogeneous systems. Consequently, whether U(V) plays a role during the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI) in homogeneous and heterogeneous systems remains a subject of debate and warrants further detailed investigation. As for the lower oxidation states of uranium, it is challenging for U(VI) to be directly reduced to U(III) or U(0) through photocatalytic reduction, as the required reduction potential is quite negative[46]. However, in a formic acid-U(VI) homogeneous photocatalytic system, spectrophotometric analysis detected the transformation of U(VI) into a mixture of U(V), U(IV), and U(III) when the pH was below 2.0[47]. This suggests that the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI) can become more complex under specific conditions.

To date, most studies suggest that U(VI) is ultimately reduced to the dark gray U(IV) precipitate in conventional photocatalytic systems[48]. However, there is some divergence in understanding the phases of U(VI) reduction products. Reports have shown that the photocatalytic reduction products of U(VI) include U3O8, U3O7, UO2+x (where x = 0 to 0.25), UO3, UO2, and mixtures of U3O7, UO4∙xH2O, etc.[21,34,45,49,50]. In the TiO2 photocatalytic reduction of U(VI) system, the reaction products appear as particulate precipitates that are deposited on the catalyst surface, resembling the electrochemical reduction of U(VI)[7,23]. Once the reaction products are separated from the system, they are readily re-oxidized to form soluble U(VI)[23,51]. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis of the products revealed that the reduced products mostly exhibit a mixed oxidation state of U(VI) and U(IV). However, the interpretation of this mixed valence state varies. For instance, Feng et al. attributed the mixed valence state to the formation of U(IV) oxides or U(IV) hydroxides[52]. Bonato and Salomone et al. suggested that this mixed valence state resulted from the formation of UO2+x (where x = 0 to 0.25)[45,53]. Meanwhile, Alhindawy et al. proposed that the mixed valence state originated from the formation of (UO2)2O2·2H2O[54]. Furthermore, some studies using XPS analysis confirmed that the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI) on TiO2 resulted in a mixture of UO3, UO2, and U3O7, while others suggested that only UO2 was present in the products[35,55,56]. Moreover, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis conducted by He et al. identified the phase information of the uranium products, revealing characteristic diffraction peaks corresponding to UO2, U3O8, and (UO2)6O2(OH)8∙6H2O[36]. However, it is worth noting that XRD analysis may struggle to distinguish between UO2 and UO2+x (where x < 0.25). Additionally, the size and content of the products are essential for effective phase analysis. When the pure water system was replaced with a high-salinity brine system, uranium oxide nanoparticles were also formed on the TiO2 surface under light irradiation. However, due to their high dispersion and extremely small particle size (approximately 6 nm), the characteristic peaks of uranium precipitation in the resulting products were not detectable in the XRD spectrum[57]. Wang et al. reported that under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, U(VI) formed different products on the surface of ferrihydrite[58]. Under anaerobic conditions, U(VI) was reduced by ·O2- radicals to form UO2+x (where x < 0.25) precipitates, while under aerobic conditions, the system generated large amounts of H2O2, which complexed with U(VI) to form UO2·xH2O precipitates. This suggests that the formation of active species in different systems is directly linked to the formation of uranium products.

Experimental condition

The performance of photocatalytic uranium extraction is significantly influenced by experimental setups and reaction conditions, including light source type, reaction temperature, pH, and the presence of coexisting ions or ligands. The spectral distribution and intensity of the light source directly influence the efficiency of the photocatalytic reaction. UV light sources, such as mercury lamps, are commonly used in experimental studies due to their high energy, which matches the bandgap of traditional photocatalysts such as TiO2. However, since UV light only constitutes about 5% of natural sunlight, researchers are focused on developing photocatalysts that can be driven by visible light or even full sunlight, such as g-C3N4 and MOFs, which demonstrate good photocatalytic activity under visible light. Adjusting the light source intensity and wavelength in laboratory experiments, especially under low light intensity conditions, can help simulate more practical scenarios where uranium extraction occurs under visible or near-infrared light[59].

The pH of the solution plays a key role in determining the chemical speciation of uranium and the surface charge of the photocatalyst. Wang et al. found that the reduction efficiency of U(VI) increases with pH value[60]. At low pH, H+ compete with U(VI) for electrons, reducing the photocatalytic activity. At pH values between 4 and 6, U(VI) mainly exists as UO2OH+, (UO2)2(OH)22+, (UO2)3(OH)5+, and (UO2)3(OH)42+, and electrostatic attraction can help capture electrons on the catalyst surface, improving uranium removal efficiency. When the pH exceeds 7, U(VI) typically transforms into species such as (UO2)3(OH)7-, (UO2)2(OH)42-, and (UO2)2(OH)3-, which exhibit electrostatic repulsion with the catalyst surface, thereby hindering adsorption and reduction[61]. Moreover, the pH of the reaction solution can influence the redox potential of the catalyst’s CB, which in turn affects the reduction capability of the photogenerated electrons. In general, as pH increases, the more negative the CB redox potential becomes, favoring uranium photocatalytic reduction[62]. Thus, it is important to evaluate the photocatalytic performance of catalysts using U solutions with pH and concentrations close to those found in target water bodies.

In addition, coexisting ions in the solution, such as Ca2+, Mg2+, and phosphates, or organic ligands, can compete with uranium for active sites on the photocatalyst or form stable complexes with uranium, thereby reducing its reducibility and affecting extraction efficiency. Gong et al. studied the photocatalytic performance of Er0.04-ZnO for U(VI) reduction in solutions containing Na+, K+, Mg2+, Sr2+, Cu2+, Fe3+, SO42-, CO32-, Br-, and Cl-, and found that the U(VI) removal efficiency only slightly decreased, indicating that Er0.04-ZnO has strong anti-interference ability[63]. In contrast, ions such as Cu2+, with a reduction potential of

Other factors influencing the photocatalytic uranium extraction process include the amount of catalyst used, uranium concentration, temperature, and dissolved O levels. For example, Liang et al. studied the effect of ZnFe2O4 catalyst dosage (0.1 to 0.6 g/L) on the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI) and found that increasing the catalyst dosage accelerated the reaction rate due to an increase in active sites, but beyond the optimal dosage, the suspension of ZnFe2O4 caused light shielding, reducing photocatalytic efficiency[68]. Thus, considering the solid-to-liquid ratio in experiments is essential to maximize the use of photocatalysts.

PHOTOCATALYTIC MATERIALS FOR URANIUM EXTRACTION

Traditional inorganic photocatalysts

The development of photocatalytic materials for uranium extraction has evolved from traditional semiconductor materials to novel materials in recent years. In the early stages of research, TiO2, as one of the earliest photocatalysts, was widely applied in the study of uranium extraction. Since 1972, Fujishima and Honda successfully achieved water splitting using irradiated TiO2, which led to TiO2 becoming a prominent photocatalyst attracting global scientific attention[70]. In the late 1980s, TiO2 gained attention for its chemical stability, low toxicity, and low cost, which made it a primary candidate in the field of photocatalytic uranium extraction. By being activated under UV light, TiO2 generates electron-hole pairs that participate in the reduction of U(VI) to U(IV), thereby facilitating uranium extraction by lowering its solubility.

However, the primary issue with TiO2 lies in its wide bandgap (approximately 3.2 eV), which restricts it to only absorb UV light[71]. Since UV light constitutes only a small portion of the solar spectrum, the photocatalytic efficiency of TiO2 remains relatively low under natural sunlight[71]. To address this limitation, researchers have gradually explored other photocatalytic materials. In the mid-1990s, materials such as zinc oxide and cadmium sulfide (CdS) were introduced into the study of uranium extraction. ZnO and CdS possess a relatively smaller bandgap compared to TiO2 (ZnO approximately 3.3 eV and CdS approximately 2.4 eV), enabling them to absorb a wider range of the light spectrum, particularly visible light, and therefore improve photocatalytic efficiency[64]. Traditional semiconductor materials, including metal oxides (e.g., TiO2, ZnO) and metal sulfides (e.g., CdS, PbS, MoS2), have played a crucial role in the development of photocatalytic uranium extraction. These materials have demonstrated promising photocatalytic activity due to their intrinsic semiconductor properties, including suitable band structures and high redox potentials. Metal oxides, particularly TiO2, have been extensively studied for photocatalytic uranium extraction due to their chemical stability, low toxicity, and cost-effectiveness. Evans et al. demonstrated that TiO2 could efficiently separate U(VI) (0.17 mM) from a 3 M phosphate waste solution under UV light[72]. Within 6 h, TiO2 removed 98% of the U(VI) from the wastewater (pH ~6), indicating the potential of photocatalytic methods to reduce and remove U(VI) from solutions containing strong ligands. In recent years, TiO2 has been extensively studied in the field of photocatalytic uranium extraction. For instance,

Figure 2. (A) The scheme of hierarchical TiOS/NHCS photocatalysts[81], Copyright 2021, Elsevier Ltd; (B) Schematic of the MnOx@TiO2@CdS@Au synthesis route and (C) TEM images[82], Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH; (D) SEM images of Co3O4@SiO2@TiO2 and (E) Co3O4@TiO2@CdS double-shelled Nanocage; (F) TEM images of Co3O4@TiO2@CdS@Au mono-shelled nanocages[83], Copyright 2023, Elsevier Ltd. TEM: Transmission electron microscopy; SEM: scanning electron microscopy.

Metal sulfides, such as CdS, PbS, and MoS2, offer narrower bandgaps (e.g., CdS ~2.4 eV), allowing them to absorb visible light and achieve higher utilization of solar energy[84]. This property enhances their photocatalytic activity in uranium extraction, especially under sunlight-driven conditions. Given that the CB position of CdS [-0.8 V vs. normal hydrogen electrode (NHE)] is more negative than the reduction potentials of UO22+/U4+ (0.267 V) and UO22+/UO2 (0.411 V), CdS is thermodynamically capable of photocatalytically reducing U(VI)[68,85]. It has been reported that the photocatalytic efficiency of CdS is highly influenced by its morphology, which affects the band structure and electron transfer processes[86]. Various morphologies of CdS have been synthesized using different methods, including 0D nanoparticles, 1D nanorods or nanowires, 2D nanosheets, 3D hollow spheres, and nanosheet assemblies[87-90]. Among them, 1D CdS has garnered significant attention due to its unique one-dimensional structure, which facilitates charge separation, transfer, and reaction processes, thereby promoting photocatalytic reactions[91]. However, the performance of 1D CdS is still hindered by issues of electron-hole recombination and photo-corrosion under extended light exposure[92]. Despite their potential, metal sulfides such as CdS, PbS, and MoS2 suffer from poor stability, particularly photo-corrosion under prolonged light exposure, which leads to a rapid degradation in photocatalytic performance[93,94]. The high synthesis costs and environmental toxicity of CdS further limit its practical applications. Similarly, although other metal sulfides, such as PbS and MoS2, show potential for uranium extraction, they exhibit poor long-term stability and limited resistance to oxidation, which restricts their widespread use in photocatalytic processes.

Another major challenge faced by both metal oxides and metal sulfides is the charge carrier recombination issue, where photogenerated electrons and holes rapidly recombine before participating in redox reactions. This process severely diminishes the overall photocatalytic efficiency. While strategies such as cocatalyst loading, heterojunction formation, and defect engineering have been explored to mitigate charge recombination, these approaches have yet to fully resolve the fundamental limitations of these traditional semiconductors. These limitations underscore the urgent need for next-generation photocatalytic materials that exhibit enhanced visible light absorption, improved stability, and higher efficiency to facilitate the large-scale application of photocatalytic uranium extraction.

Development of novel photocatalysts

In recent years, with the increasing demands for higher efficiency and stability in photocatalytic uranium extraction, researchers have shifted towards developing new photocatalytic materials. These materials not only exhibit better visible light absorption but also maintain high stability and long-term operational efficiency. The novel photocatalysts include organic polymers, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), covalent organic frameworks (COFs), and various composite materials, all of which show promising potential for use in photocatalytic uranium extraction. MOFs are characterized by high surface area and tunable electronic structures, which enhance their photocatalytic properties for uranium extraction. COFs exhibit high stability and well-ordered structures, making them promising candidates for photocatalysis. The introduction of these novel materials has significantly improved photocatalytic efficiency and extended the application range for uranium extraction.

Organic polymers

g-C3N4, an organic polymer in the field of photocatalytic uranium reduction, has become a research focus in recent years due to its relatively narrow bandgap (~2.7 eV), excellent chemical stability, tunable electronic properties, and versatile morphology[95-97]. The CB of g-C3N4 is approximately -1.1 V (vs. NHE), which is more negative than the reduction potentials of UO22+/U4+ (0.267 V) and UO22+/UO2 (0.411 V), making it thermodynamically capable of driving the reduction of U(VI)[98]. Additionally, g-C3N4 is easily synthesized through a simple process, using various low-cost nitrogen-containing precursors such as melamine, urea, mono- or dicyanamide, and thiourea, making it economically feasible as a photocatalyst[99,100]. It also exhibits good photocatalytic activity and low environmental toxicity, which makes it promising for applications in seawater uranium extraction and uranium wastewater treatment. However, g-C3N4 still faces several challenges, including limited intrinsic active sites, significant recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes, small surface area, and low visible light utilization efficiency, which restrict its overall performance in photocatalytic reactions. To enhance the photocatalytic reduction efficiency of g-C3N4 for U(VI), current research focuses on optimizing its electronic structure through methods such as element doping, molecular doping, defect introduction, and the construction of heterojunctions to improve its photocatalytic activity. For example, Yu et al. successfully developed an inexpensive g-C3N4-based photocatalyst (AO-C3N4) with amidoxime groups for photo-assisted uranium extraction, with the synthesis strategy shown in Figure 3A[101]. The amidoxime groups served as binding sites for U(VI), while also improving carrier separation efficiency and shortening the band gap, enhancing uranium capture. Additionally, the generated ROS under light endowed AO-C3N4 with excellent antibacterial properties, preventing marine biofouling. AO-C3N4 achieved 850 μg/g uranium extraction from natural seawater after one week of sunlight exposure, 1.73 times higher than without light. Hu et al. successfully developed cyano-functionalized graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4-CN) with an isosite structure for efficient photocatalytic uranium extraction from seawater [Figure 3B][29]. The cyano groups enhance charge separation, increase electron enrichment, and improve U(VI) adsorption capacity and selectivity, achieving a saturated uranium extraction capacity of 2,644.3 mg/g, outperforming most g-C3N4-based photocatalysts, and showing excellent performance under solar light. Metal doping typically introduces new impurity energy levels within the semiconductor's bandgap, which narrows the bandgap width and enhances the photocatalytic activity by improving the light absorption range. Additionally, metal dopants can serve as electron/hole traps, promoting the separation of photogenerated charge carriers and reducing recombination. For example, Gong et al. introduced Fe doping into TiO2 crystals by creating anion vacancies, significantly enhancing the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI)[79].

Figure 3. (A) Illustration on the synthesized process of AO-C3N4[101], Copyright 2023, Elsevier Ltd; (B) Schematic diagram of preparing

Non-metal doping, such as O, phosphorus (P), sulfur (S), fluorine (F), and others, can further enhance the photocatalytic performace by increasing the conjugated π-electron systems in the material, improving electron conductivity and promoting the migration and separation of charge carriers. For example,

In addition to g-C3N4, polymers have also demonstrated some photocatalytic reduction capabilities for uranium. Ma et al. developed a bifunctional porous aromatic framework (PAF-AN2T8-AO) combining adsorption and photocatalytic enrichment groups for efficient uranium recovery from nuclear wastewater

MOFs

In recent years, MOFs have gained widespread attention due to their high surface area, porosity, and tunable electronic structures. MOFs are a class of porous materials composed of metal ions/clusters coordinated with organic linkers, possessing well-defined molecular structural units, adjustable functional groups, and effective active sites[113]. These properties allow MOFs to function simultaneously as photosensitizers (organic ligands) and catalytic centers (metal clusters/nodes). This unique structure enables MOFs to absorb visible light and efficiently separate photogenerated electrons and holes, making them promising candidates for photocatalytic uranium extraction. To date, there have been fewer reports on the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI) by MOFs compared to their adsorption-based removal of U(VI). Their behavior under light irradiation is similar to that of semiconductor photocatalysts, attributed to metal charge transitions [ligand to metal charge transitions (LMCT)], metal to ligand charge transitions (MLCT), or π-π* transitions in the aromatic ligands[114]. Li et al. proposed a post-synthetic ligand functionalization strategy to create phosphoric acid-functionalized and amine-functionalized Zr-based MOFs (PN-PCN-222), achieving selective uranium capture and photocatalytic reduction under visible light[50]. This modified MOF demonstrated excellent uranium extraction performance across a wide range of uranium concentrations and pH values.

However, despite the abundant metal nodes in MOFs serving as active sites, their suitability as photocatalysts remains limited. The metal/ligand coordination structure dictates their wide bandgap (Eg > 5.5 eV), preventing efficient absorption of visible light[115]. For example, ZIF-8 [Zn6(mIm)12: mIm = 2-methylimidazole ligand] has a bandgap of 5.8 eV, which makes it unsuitable as a photocatalyst under UV-visible light[116]. To address this limitation, selecting appropriate MOF components can significantly enhance their photocatalytic activity. For instance, Zhang et al. designed and synthesized a polyoxometalate (POM)-organic framework material (SCU-19) with a rare inclined polycatenation structure[117]. They conducted uranium separation experiments, demonstrating that under visible light irradiation, an additional U(VI) photocatalytic reduction mechanism occurs, achieving higher uranium removal rates and faster adsorption kinetics without reaching saturation.

Furthermore, to overcome these challenges, researchers have employed various modification strategies, such as functionalizing MOF ligands, surface grafting of functional groups, and forming heterojunctions with other semiconductors, to improve the photocatalytic performance and broaden the application scope of MOFs. For example, Liu et al. developed a bifunctional photocatalyst, MOF525@BDMTp, with MOF525 as the core and BDMTp as the shell, utilizing a type-II heterojunction strategy [Figure 5A][118]. This design improves electron-hole separation and carrier migration, enhancing the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI) and oxidation of chlorpyrifos (CP). The built-in electric field further boosts electron transfer, activating U(VI) binding sites. MOF525@BDMTp achieved a U(VI) removal rate of 625.0 mg/g and 94.0% CP degradation, demonstrating its effectiveness in complex environments. Bi et al. developed Ti-MOF@DATp, a bifunctional photocatalyst that efficiently reduces U(VI) and oxidizes tetracycline through a Z-scheme heterojunction [Figure 5B][119]. The catalyst achieved 96% U(VI) and 90% tetracycline removal from their mixture, significantly outperforming individual removal, with a removal rate constant 55 times higher for the mixture than U(VI) alone. In the study by Chen et al., UiO-66-NH2/black phosphorus quantum dots (MOF/BPQDs) heterojunctions were anchored on carboxyl cellulose nanofiber aerogels for efficient uranium adsorption [Figure 5C and D][120]. Under light irradiation, BP@CNF-MOF demonstrated a 55.3% increase in uranium adsorption efficiency, reaching 6.77 mg-U per g after 6 weeks in natural seawater, while also effectively destroying marine bacteria through photocatalytic generation of ROS [Figure 5E].

Figure 5. (A) The synthesis of MOF525@BDMTp and the mechanism of removing U(VI)[118], Copyright 2023, Elsevier Ltd; (B) The composite material Ti-MOF@DATp[119], Copyright 2024, Elsevier Ltd; Images of lightweight (C) CNF and (D) BP@CNF-MOF aerogels, (E) Uranium extraction of BP@CNF-MOF in natural seawater for 6 weeks under light and dark conditions[120], Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH.

COFs

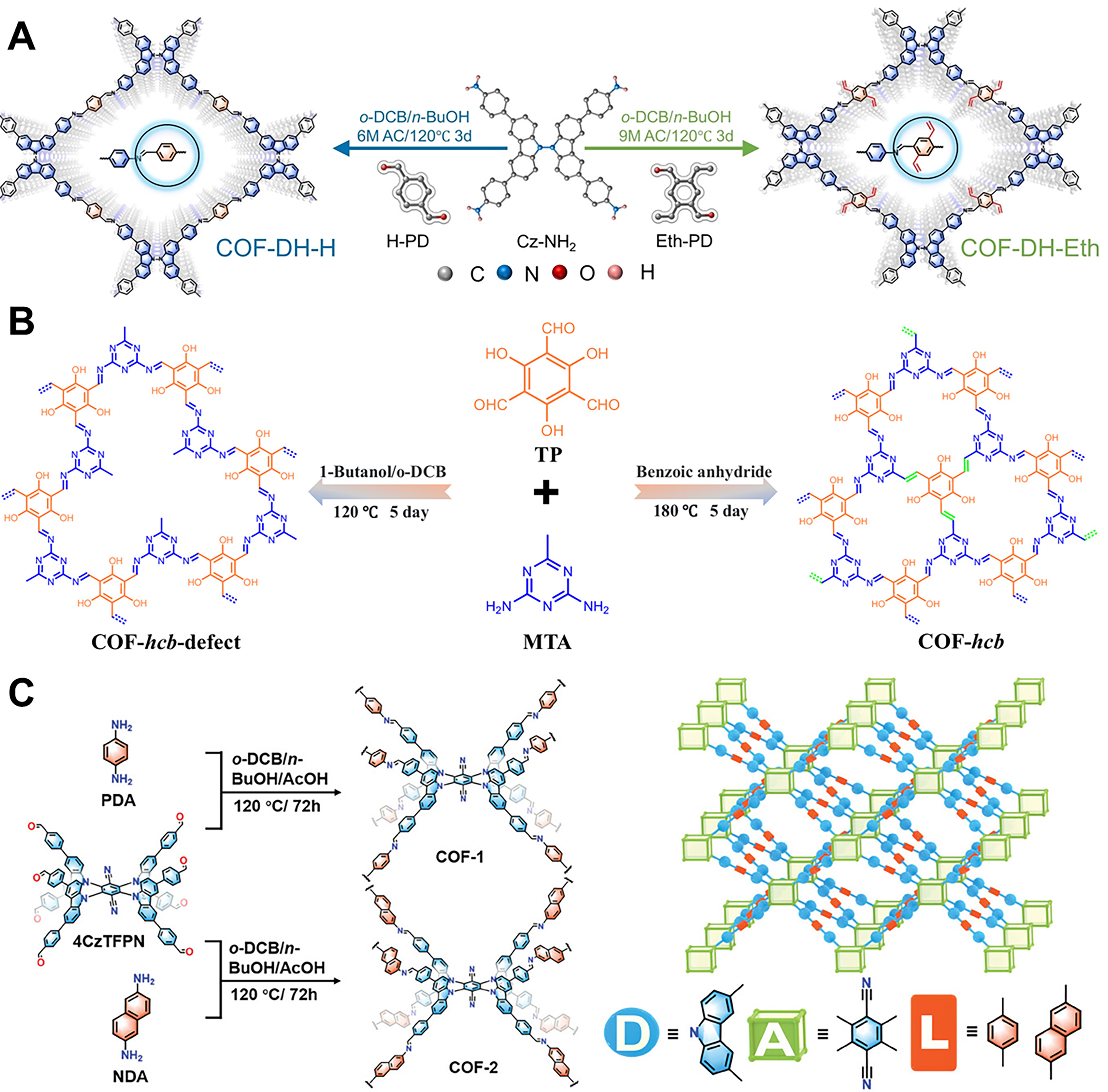

COFs are another class of materials that have gained attention for their high chemical stability, well-defined pore structures, and tunable electronic properties. They are crystalline materials held together by strong covalent bonds, and they offer excellent chemical stability. COFs can be designed to absorb visible light and facilitate photocatalytic reactions, making them ideal candidates for uranium extraction. Cui et al. reported the synthesis of a semiconductor COF with excellent photocatalytic activity[121]. The high photocatalytic activity of NDA-TN-AO (A highly planar conjugated naphthalene-based sp2) enabled it to generate ROS that disrupted bacteria, demonstrating significant anti-biofouling ability. Additionally, NDA-TN-AO facilitated the reduction of adsorbed U(IV) to insoluble U(IV), significantly improving uranium extraction capabilities. Due to the photoelectric effect, NDA-TN-AO displayed a strong electrostatic attraction toward [UO2(CO3)3]4- ions, even in natural seawater. Under simulated sunlight, the uranium adsorption capacity of NDA-TN-AO reached 6.07 mg/g, which was 1.33 times higher than under dark conditions. A COF-based adsorption-photocatalysis strategy for selective uranium removal from seawater without sacrificial reagents was developed by Hao et al.[122]. The quaternary COF [Figure 6A], COF 2-Ru-AO, with electron-rich and electron-deficient linkers, achieved a high uranium uptake capacity of 2.45 mg/g/day and demonstrated excellent anti-biofouling properties, surpassing most current adsorbents. Another novel strategy using Ti-oxo clusters (TiOCs) encapsulated within a photosensitive COF (TiOCs∈COF-TZ) [Figure 6B] for efficient photocatalytic uranium extraction[123]. This approach allows TiOCs to reduce [UO2(CO3)3]4- in natural seawater under visible-light irradiation, achieving 89.9% uranium extraction. Compared to unloaded COF-TZ and surface-loaded TiOCs@COF-TZ, TiOCs∈COF-TZ demonstrates superior catalytic activity and efficiency.

The development of COFs has been focused on improving their electronic properties to enhance charge separation and light absorption. Chen et al. synthesized a series of COFs with varying excited-state electron distributions, charge transport properties, and porosity characteristics [Figure 7A][124]. Through a combination of experimental studies and theoretical calculations, they investigated and optimized the material’s performance, achieving a uranium extraction capacity of 6.84 mg/g from natural seawater.

Figure 7. (A) Different structures of COF-1 to COF-4 to modulate the excited state electronic structure and charge transport properties for tuning the photocatalytic activities for uranium extraction[124], Copyright 2023, Springer Nature; (B) Illustration of the energy levels summarizing the main processes involved in charge transfer[125], Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; (C) Preferential growth of N3-COF along the 001 direction and (D) SEM and TEM (inset) images of N3-COF and N3-COFx[127], Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society; (E) Recent performance of photocatalysts used for uranium extraction from seawater. Blue: Total uranium uptake capacity; Orange: everyday uranium uptake capacity. COFs: Covalent organic frameworks; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; SEM: scanning electron microscopy.

In addition to the strategies mentioned above, recent studies have also explored a novel approach where COF materials are used for photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production, which is then utilized to reduce uranium [U(VI)] from seawater. This approach capitalizes on the ability of COFs to generate H2O2 under light irradiation, which can serve as an effective reagent for U(VI). This dual-function mechanism photocatalytic H2O2 generation followed by uranium reduction, adds another layer of efficiency to COF-based photocatalysts, making them even more promising for environmental remediation applications.

Figure 8. (A) Synthesis piezo-photocatalytic COFs of COF-DH-H and COF-DH-Eth[128], Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; (B) The synthesis of COF-hcb and COF-hcb-defect[129], Copyright 2024, Chinese Chemical Society; (C) Illustration of the synthesis of 3D COFs and topology[130], Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH. COFs: Covalent organic frameworks.

CHALLENGES IN U(VI) PHOTOCATALYTIC EXTRACTION

A wide range of photocatalysts have been synthesized for photocatalytic extraction of U(VI) from aqueous solutions, with high selectivity and efficiency. Key strategies for enhancing photocatalytic activity include the design of tunable structures, optimization of band gaps, incorporation of active sites and functional groups, and improving stability and reusability. However, most photocatalysts are only verified under artificial light sources, rather than sunlight, limiting their practical application. This gap not only increases operational costs but also restricts the evaluation of these catalysts under real-world conditions. Future research should focus on expanding the light-harvesting capacity of photocatalysts, particularly in the visible to near-infrared spectrum, which is a critical direction for innovation in photocatalysis. Moreover, achieving high photocatalytic efficiency under low light intensity requires further reduction in the recombination rate of photogenerated electron-hole pairs. Many photocatalytic systems currently rely on sacrificial agents, which can introduce new environmental and safety concerns. Different kinds of active free radicals such as ·OH, ·O2-, 1O2, electrons, etc., are generated to promote selective separation of U(VI) from complex systems. Future efforts should focus on synthesizing cost-effective photocatalysts with high stability, visible light absorption, efficient electron-hole pair separation, and selective U(VI) binding, particularly in the presence of competing metal ions. In addition, the yield and purity analysis of uranium after photocatalysis are of great significance for evaluating the economic benefits of photocatalytic systems. The proportion of uranium extracted from the initial solutions is directly related to the production cost and efficiency. Future photocatalytic system designs should emphasize reducing material consumption while maximizing uranium recovery rates. Furthermore, thorough assessment of the purity and impurity profiles of the extracted uranium is essential, as higher-purity products can substantially lower downstream processing costs, thereby improving the overall economic performance of the extraction process.

Significant progress has been made in identifying the final products of U(VI) reduction via photocatalysis. However, the characterization of intermediate uranium species remains limited. Identifying these intermediates is crucial for elucidating the underlying mechanisms of U(VI) reduction. The pathways for U(VI) reduction remain a topic of debate, with proposed mechanisms including direct electron transfer, U(V) self-disproportionation, and free radical-mediated reduction. In this context, in-situ characterization techniques offer valuable experimental insights for addressing key challenges in uranium photoreduction. These include assessing the stability of the photocatalysts under reaction system, identifying intermediate species and their structural relationship, pinpointing photocatalytic active sites, and understanding the influence of the reaction environment on the reduction process. Over the past few decades, advancements in spectroscopy and microscopy have significantly enhanced our ability to investigate photocatalytic processes. Techniques such as in-situ TEM, high-angle annular dark-field imaging (HAADF)-TEM, XPS, and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) have proven instrumental in identifying intermediate uranium species during U(VI) photoreduction. Furthermore, the application of in-situ XPS, Raman spectroscopy, and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) enables real-time monitoring of the coordination and transformation of uranium species on photocatalyst surfaces. These techniques provide critical insights into the structure-activity relationships between photocatalysts and uranium, thereby deepening our understanding of the underlying photocatalytic mechanisms. Although various quenching agents have been employed to investigate the relative contributions of reactive species in U(VI) photoreduction, these approaches primarily offer qualitative insights into their roles within photocatalytic processes. The precise quantitative contributions of individual reactive species remain unclear, and the synergistic effects of multiple species are often underestimated or overlooked. One of the primary challenges lies in the real-time, online analysis of these reactive species, rendering photocatalytic processes akin to “black-box” phenomena. Researchers typically rely on EPR spectroscopy and theoretical simulations to infer photocatalytic mechanisms. However, advanced spectroscopic techniques, particularly those enabling online and real-time characterization, offer greater accuracy in elucidating the roles of these reactive species. In the near future, the integration of such real-time analytical methods with theoretical calculations will be crucial for unraveling photocatalytic mechanisms and guiding the rational design of more efficient photocatalysts. On the other hand, theoretical calculation is also an important method to analyze the photocatalytic mechanism, which is of guiding significance for the accurate design of high-efficiency photocatalysts. At present, the theoretical research of photoelectricity mainly focuses on the energy band structure of photocatalyst and adsorption energy of uranium, while there are few studies on the active center of photocatalysts, target reaction species and structural dynamics evolution of different reaction stages. Traditional theoretical calculations are often conducted under vacuum conditions, neglecting the complex physical and chemical effects introduced by external light and electric fields present in actual photocatalytic systems. This discrepancy leads to deviations between theoretical predictions and experimental observations. To bridge this gap, there is a pressing need for computational chemists to develop more sophisticated models that accurately simulate real-world conditions, including illumination, electric fields, and reaction environments. In addition, integrating theoretical calculations with machine learning and artificial intelligence represents a promising direction for future research. The combination of computational simulations, large-scale experimental data, and machine learning algorithms will facilitate the rapid screening of efficient photocatalysts and provide deeper insights into complex reaction pathways and mechanisms. In the near future, this in-situ analysis and theoretical calculation will play an important guiding role in the synthesis of photocatalysts and evaluation of photocatalytic mechanisms.

To date, research on photocatalytic processes has predominantly focused on catalysts in powder form, which presents challenges for catalyst recovery and reuse, potentially leading to secondary environmental pollution. Developing photocatalysts in alternative forms such as membranes, gels, or foams offers a promising solution to these recycling issues and can simplify downstream product purification. However, these forms may exhibit reduced visible light-harvesting efficiency compared to powder-based catalysts. Therefore, a careful balance must be struck between facilitating catalyst recovery, minimizing secondary pollution, and maintaining high photocatalytic activity. While photocatalytic U(VI) extraction technologies have demonstrated promising performance under controlled laboratory conditions, there remains a significant gap in their experimental validation in real-world scenarios, such as marine environments or uranium-containing radioactive wastewater. In the actual complex environment of uranium-containing wastewater, the concentration of coexisting ions and organic matter is tens of thousand times higher than those typically encountered in laboratory settings. This is particularly true for radioactive wastewater generated during spent fuel reprocessing, which contains a complex mixture of inorganic and organic components. Such conditions pose significant challenges for the practical application of photocatalysts. In the field of uranium extraction from seawater, photocatalytic reduction can significantly improve the kinetics, uranium extraction capacity and antibacterial properties of uranium extraction. However, these promising results remain largely unverified in actual marine environments, as comprehensive sea trials are still lacking. The complexity of natural seawater characterized by a diverse ionic composition and a low uranium concentration (~3.3 ppb) further complicates efforts to achieve efficient uranium enrichment using current photocatalytic technologies. At present, there is a lack of effective technical solutions for deploying photocatalysts in open environments such as those influenced by waves and ocean currents. Additionally, the impact of seawater microorganisms on photocatalytic processes remains an area requiring further investigation. Developing scalable, integrated photocatalytic systems and designing materials specifically suited for marine environments are critical directions for advancing seawater uranium extraction. In practical applications, many complex factors need to be considered, such as high concentration of competitive ions, radioactive pollution, biofouling and erosion from water currents. Photocatalytic technologies should be designed with these real-world conditions in mind, ensuring that materials are adapted to meet practical demands. With the development of techniques, photocatalytic extraction of U(VI) from complex conditions will contribute greatly to the supply of nuclear fuel in future.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVE

The recovery of uranium by photocatalytic technology is of great strategic significance for the sustainable development of nuclear energy and uranium resources. In recent years, significant research progress has been made in the extraction of uranium by photocatalytic technology. These advances mainly include photocatalyst structure design, application technology development, and reaction species analysis, which have laid a solid foundation for improving the key performance parameters such as selectivity, reaction kinetics, and uranium extraction capacity. However, the real promotion and application of photocatalytic uranium technology still face the following crucial problems and challenges. The preparation of most photocatalysts requires a complex synthesis process and a lot of time and cost. How to develop a universal photocatalyst is particularly important. Based on the application scenarios of photocatalysis, combined with physical and chemical characterization methods, machine learning, artificial intelligence and theoretical simulation, it will help to construct efficient photocatalysts. The current photocatalytic activity of the photocatalyst is still insufficient, and the light absorption capacity is weak in visible light. Most photocatalytic processes require the addition of sacrificial reagents. Therefore, it is necessary to accurately regulate the energy level structure and band gap of COFs to improve the photocatalytic activity.

Although photocatalytic technology has made some achievements in the identification of uranium reduction products, there is still a research gap in the identification of intermediate products in the uranium photoreduction process. An in-depth analysis of the reaction intermediates is helpful to reveal the potential mechanism of uranium reduction and provide theoretical guidance for the precise design and structural optimization of photocatalysts. Aimed at the energy and electron transfer process between the photocatalyst and the reactants or intermediates in photocatalysis, multi-dimensional and high space-time resolution characterization methods (such as time-resolved X-ray absorption spectroscopy, femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy, etc.), combined with in-situ characterization techniques [such as in-situ Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), in-situ XRD, in-situ EPR, etc.], are used to indicate the dynamic interaction information between electrons, free radicals or free intermediates and active sites, revealing the dynamic process of charge transfer, structural changes and mechanism of the catalytic center in the photocatalytic reaction. Combined with computational chemistry, the analysis of the energy band structure and electron transfer path of photocatalytic will help screen out efficient photocatalysts, clarify the evolution process of uranium species structure, and provide feedback to guide photocatalyst design and mechanism research.

Based on the application scenarios, research and development of photocatalysts adapted to the practical environment is an important link to promote the effective application of scientific and technological achievements, and realize the high-quality development of photocatalytic uranium extraction technology from laboratory research to industrial application. In practical application, the photocatalyst needs to have both high stability and multiple recycling, which is also a necessary condition for practical application. At present, most of the photocatalysts are synthesized on a small scale in the laboratory, and there is still a long way to go to realize industrial large-scale synthesis. Furthermore, photocatalysts with excellent performance can be screened out to integrate into photocatalytic devices, which can avoid the interference of environmental factors and simplify the separation steps. Photocatalytic uranium extraction technology shows great potential in energy saving and environmental protection. According to the continuous research and optimization, it is expected to achieve efficient and economical uranium extraction in the near future, providing an important guarantee for the sustainable development of nuclear energy.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Contributed to the investigation, data analysis and draft writing: Xie, Y.; Chen, H.

Contributed to investigations and editing: Li, J.; Liu, X.; Hao, M.

Contributed to funding acquisition, supervision, review and editing: Chen, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.

Contributed to investigations and editing: Wakeel, M.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

Financial supports from the National Science Foundation of China (22341602; U2341289) are acknowledged.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Sholl, D. S.; Lively, R. P. Seven chemical separations to change the world. Nature 2016, 532, 435-7.

2. Xie, Y.; Liu, Z.; Geng, Y.; et al. Uranium extraction from seawater: material design, emerging technologies and marine engineering. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 97-162.

3. Ye, Y.; Jin, J.; Han, W.; et al. Spontaneous electrochemical uranium extraction from wastewater with net electrical energy production. Nat. Water. 2023, 1, 887-98.

4. Yang, L.; Xiao, H.; Qian, Y.; et al. Bioinspired hierarchical porous membrane for efficient uranium extraction from seawater. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 71-80.

5. Sun, Q.; Aguila, B.; Perman, J.; et al. Bio-inspired nano-traps for uranium extraction from seawater and recovery from nuclear waste. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1644.

6. Yuan, Y.; Liu, T.; Xiao, J.; et al. DNA nano-pocket for ultra-selective uranyl extraction from seawater. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5708.

7. Liu, C.; Hsu, P.; Xie, J.; et al. A half-wave rectified alternating current electrochemical method for uranium extraction from seawater. Nat. Energy. 2017, 2, 17007.

8. Mei, D.; Liu, L.; Yan, B. Adsorption of uranium (VI) by metal-organic frameworks and covalent-organic frameworks from water. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 475, 214917.

9. Tamada M. Current status of technology for collection of uranium from seawater. In International seminar on nuclear war and planetary emergencies-42nd session. 2010; pp 243-52.

10. Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Hao, M.; et al. Functionalized iron-nitrogen-carbon electrocatalyst provides a reversible electron transfer platform for efficient uranium extraction from seawater. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2106621.

11. Cai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, Z.; et al. Highly efficient uranium extraction by a piezo catalytic reduction-oxidation process. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2022, 310, 121343.

12. Meng, C.; Du, M.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Open-framework vanadate as efficient ion exchanger for uranyl removal. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 9456-65.

13. Yang, J.; Acharjya, A.; Ye, M. Y.; et al. Protonated imine-linked covalent organic frameworks for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 19797-803.

14. Huang, N. Y.; He, H.; Liu, S.; et al. Electrostatic attraction-driven assembly of a metal-organic framework with a photosensitizer boosts photocatalytic CO2 reduction to CO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17424-30.

15. Shiraishi, Y.; Takii, T.; Hagi, T.; et al. Resorcinol-formaldehyde resins as metal-free semiconductor photocatalysts for solar-to-hydrogen peroxide energy conversion. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 985-93.

16. Qin, C.; Wu, X.; Zhou, W.; et al. Urea/thiourea imine linkages provide accessible holes in flexible covalent organic frameworks and dominates self-adaptivity and exciton dissociation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202418830.

17. Wu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Functional nanomaterials for selective uranium recovery from seawater: material design, extraction properties and mechanisms. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 483, 215097.

18. Liu, X.; Pang, H.; Liu, X.; et al. Orderly porous covalent organic frameworks-based materials: superior adsorbents for pollutants removal from aqueous solutions. Innovation 2021, 2, 100076.

19. Tang, N.; Liang, J.; Niu, C.; et al. Amidoxime-based materials for uranium recovery and removal. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020, 8, 7588-625.

20. Xie, Y.; Yu, L.; Chen, L.; et al. Recent progress of radionuclides separation by porous materials. Sci. China. Chem. 2024, 67, 3515-77.

21. Amadelli, R.; Maldotti, A.; Sostero, S.; Carassiti, V. Photodeposition of uranium oxides onto TiO2 from aqueous uranyl solutions. Faraday. Trans. 1991, 87, 3267.

22. Chen, T.; Yu, K.; Dong, C.; et al. Advanced photocatalysts for uranium extraction: elaborate design and future perspectives. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 467, 214615.

23. Li, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Photoconversion of U(VI) by TiO2: an efficient strategy for seawater uranium extraction. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 365, 231-41.

24. Lei, J.; Liu, H.; Yuan, C.; et al. Enhanced photoreduction of U(VI) on WO3 nanosheets by oxygen defect engineering. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 416, 129164.

25. Linsebigler, A. L.; Lu, G.; Yates, J. T. Photocatalysis on TiO2 surfaces: principles, mechanisms, and selected results. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 735-58.

26. Filippov, T. N.; Svintsitskiy, D. A.; Chetyrin, I. A.; et al. Photocatalytic and photochemical processes on the surface of uranyl-modified oxides: an in situ XPS study. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2018, 58, 81-90.

27. Chen, T.; Liu, B.; Li, M.; et al. Efficient uranium reduction of bacterial cellulose-MoS2 heterojunction via the synergistically effect of Schottky junction and S-vacancies engineering. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 406, 126791.

28. Nosaka, Y.; Nosaka, A. Y. Generation and detection of reactive oxygen species in photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11302-36.

29. Hu, E.; Chen, Q.; Gao, Q.; et al. Cyano-functionalized graphitic carbon nitride with adsorption and photoreduction isosite achieving efficient uranium extraction from seawater. Adv. Funct. Materials. 2024, 34, 2312215.

30. Jiang, X.; Xing, Q.; Luo, X.; et al. Simultaneous photoreduction of Uranium(VI) and photooxidation of Arsenic(III) in aqueous solution over g-C3N4/TiO2 heterostructured catalysts under simulated sunlight irradiation. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2018, 228, 29-38.

31. Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Carboxyl groups on g-C3N4 for boosting the photocatalytic U(VI) reduction in the presence of carbonates. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 414, 128810.

32. Gaya, U. I.; Abdullah, A. H. Heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants over titanium dioxide: a review of fundamentals, progress and problems. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C. Photochem. Rev. 2008, 9, 1-12.

33. Li, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. An overview and recent progress in the heterogeneous photocatalytic reduction of U(VI). J. Photochem. Photobiol. C. Photochem. Rev. 2019, 41, 100320.

34. Kim, Y. K.; Lee, S.; Ryu, J.; Park, H. Solar conversion of seawater uranium (VI) using TiO2 electrodes. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2015, 163, 584-90.

35. Hu, L.; Yan, X.; Zhang, X.; Shan, D. Integration of adsorption and reduction for uranium uptake based on SrTiO3/TiO2 electrospun nanofibers. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 428, 819-24.

36. He, H.; Zong, M.; Dong, F.; et al. Simultaneous removal and recovery of uranium from aqueous solution using TiO2 photoelectrochemical reduction method. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2017, 313, 59-67.

37. Wu, Y.; Pang, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. Environmental remediation of heavy metal ions by novel-nanomaterials: a review. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 246, 608-20.

38. Xu, R.; Cui, W.; Zhang, C.; et al. Vinylene-linked covalent organic frameworks with enhanced uranium adsorption through three synergistic mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 419, 129550.

39. Endrizzi, F.; Leggett, C. J.; Rao, L. Scientific basis for efficient extraction of uranium from seawater. I: understanding the chemical speciation of uranium under seawater conditions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 4249-56.

40. Endrizzi, F.; Rao, L. Chemical speciation of uranium(VI) in marine environments: complexation of calcium and magnesium ions with [(UO2)(CO3)3]4- and the effect on the extraction of uranium from seawater. Chemistry 2014, 20, 14499-506.

41. Abney, C. W.; Mayes, R. T.; Saito, T.; Dai, S. Materials for the recovery of uranium from seawater. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13935-4013.

42. Shi, S.; Qian, Y.; Mei, P.; et al. Robust flexible poly(amidoxime) porous network membranes for highly efficient uranium extraction from seawater. Nano. Energy. 2020, 71, 104629.

43. Hao, X.; Chen, R.; Liu, Q.; et al. A novel U(vi)-imprinted graphitic carbon nitride composite for the selective and efficient removal of U(vi) from simulated seawater. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2018, 5, 2218-26.

44. Miyake, C.; Nakase, T.; Sano, Y. EPR study of uranium (V) species in photo-and electrolytic reduction processes of UO2NO3)2-2TBP. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 1993, 30, 1256-60.

45. Salomone, V. N.; Meichtry, J. M.; Schinelli, G.; Leyva, A. G.; Litter, M. I. Photochemical reduction of U(VI) in aqueous solution in the presence of 2-propanol. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. Chem. 2014, 277, 19-26.

46. Bard AJ, Parsons R, Jordan J. Standard potentials in aqueous solution, 1st ed.; Routledge, 1985.

47. Salomone, V. N.; Meichtry, J. M.; Litter, M. I. Heterogeneous photocatalytic removal of U(VI) in the presence of formic acid: U(III) formation. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 270, 28-35.

48. Lu, C.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, S.; et al. Photocatalytic reduction elimination of UO22+ pollutant under visible light with metal-free sulfur doped g-C3N4 photocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2017, 200, 378-85.

49. Li, Z. J.; Huang, Z. W.; Guo, W. L.; et al. Enhanced photocatalytic removal of uranium(VI) from aqueous solution by magnetic TiO2/Fe3O4 and its graphene composite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 5666-74.

50. Li, H.; Zhai, F.; Gui, D.; et al. Powerful uranium extraction strategy with combined ligand complexation and photocatalytic reduction by postsynthetically modified photoactive metal-organic frameworks. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2019, 254, 47-54.

51. Chen, J.; Ollis, D. F.; Rulkens, W. H.; Bruning, H. Photocatalyzed deposition and concentration of soluble uranium(VI) from TiO2 suspensions. Colloids. Surf. A. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1999, 151, 339-49.

52. Feng, J.; Yang, Z.; He, S.; et al. Photocatalytic reduction of Uranium(VI) under visible light with Sn-doped In2S3 microspheres. Chemosphere 2018, 212, 114-23.

53. Bonato, M.; Allen, G.; Scott, T. Reduction of U(VI) to U(IV) on the surface of TiO2 anatase nanotubes. Micro. Nano. Lett. 2008, 3, 57-61.

54. Alhindawy, I. G.; Mira, H. I.; Youssef, A. O.; et al. Cobalt doped titania-carbon nanosheets with induced oxygen vacancies for photocatalytic degradation of uranium complexes in radioactive wastes. Nanoscale. Adv. 2022, 4, 5330-42.

55. Lee, S.; Kang, U.; Piao, G.; Kim, S.; Han, D. S.; Park, H. Homogeneous photoconversion of seawater uranium using copper and iron mixed-oxide semiconductor electrodes. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2017, 207, 35-41.

56. Wang, G.; Zhen, J.; Zhou, L.; Wu, F.; Deng, N. Adsorption and photocatalytic reduction of U(VI) in aqueous TiO2 suspensions enhanced with sodium formate. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2015, 304, 579-85.

57. Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Efficient recovery of uranium from saline lake brine through photocatalytic reduction. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 308, 113007.

58. Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Ding, Z.; et al. Light promotes the immobilization of U(VI) by ferrihydrite. Molecules 2022, 27, 1859.

59. Yu, K.; Jiang, P.; Yuan, H.; He, R.; Zhu, W.; Wang, L. Cu-based nanocrystals on ZnO for uranium photoreduction: plasmon-assisted activity and entropy-driven stability. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2021, 288, 119978.

60. Wang, T.; Zhang, Z. B.; Dong, Z.; Cao, X.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, Y. H. A facile synthesis of g-C3N4/WS2 heterojunctions with enhanced photocatalytic reduction activity of U(VI). J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2022, 331, 577-86.

61. Han, R.; Hu, M.; Zhong, Q.; et al. Perfluorooctane sulphonate induces oxidative hepatic damage via mitochondria-dependent and NF-κB/TNF-α-mediated pathway. Chemosphere 2018, 191, 1056-64.

62. Ye, Y.; Jin, J.; Chen, F.; et al. Removal and recovery of aqueous U(VI) by heterogeneous photocatalysis: progress and challenges. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 138317.

63. Gong, X.; Tang, L.; Wang, R.; et al. Achieving efficient photocatalytic uranium extraction within a record short period of 3 min by Up-conversion erbium doped ZnO nanosheets. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 138044.

64. Liu, H.; Lei, J.; Gong, C.; et al. In-situ oxidized tungsten disulfide nanosheets achieve ultrafast photocatalytic extraction of uranium through hydroxyl-mediated binding and reduction. Nano. Res. 2022, 15, 8810-8.

65. Zhang, P.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Song, J.; Huang, J.; Li, P. Highly efficient uranium (VI) remove from aqueous solution using nano-TiO2-anchored polymerized dopamine-wrapped magnetic photocatalyst. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138796.

66. Lei, J.; Liu, H.; Zhou, L.; et al. Progress and perspective in enrichment and separation of radionuclide uranium by biomass functional materials. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144586.

67. He, P.; Zhang, L.; Wu, L.; et al. Synergistic effect of the sulfur vacancy and schottky heterojunction on photocatalytic uranium immobilization: the thermodynamics and kinetics. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 2242-50.

68. Liang, P.; Yuan, L.; Deng, H.; et al. Photocatalytic reduction of uranium(VI) by magnetic ZnFe2O4 under visible light. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2020, 267, 118688.

69. Lu, C.; Chen, R.; Wu, X.; et al. Boron doped g-C3N4 with enhanced photocatalytic UO22+ reduction performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 360, 1016-22.

70. Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37-8.

71. Jeon, J.; Kweon, D. H.; Jang, B. J.; Ju, M. J.; Baek, J. Enhancing the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 catalysts. Adv. Sustainable. Syst. 2020, 4, 2000197.

72. Evans, C. J.; Nicholson, G. P.; Faith, D. A.; Kan, M. J. Photochemical removal of uranium from a phosphate waste solution. Green. Chem. 2004, 6, 196-7.

73. Liu, N.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; et al. Magnetron sputtering ultra-thin TiO2 films for photocatalytic reduction of uranium. Desalination 2022, 543, 116121.

74. Liu, G.; Yang, H. G.; Wang, X.; et al. Visible light responsive nitrogen doped anatase TiO2 sheets with dominant {001} facets derived from TiN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 12868-9.

75. Yu, J.; Low, J.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, P.; Jaroniec, M. Enhanced photocatalytic CO2-reduction activity of anatase TiO2 by coexposed {001} and {101} facets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8839-42.

76. Yang, H. G.; Sun, C. H.; Qiao, S. Z.; et al. Anatase TiO2 single crystals with a large percentage of reactive facets. Nature 2008, 453, 638-41.

77. Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Deng, J.; Deng, W.; Zhao, Y. Photocatalytic reduction of uranyl ions over anatase and rutile nanostructured TiO2. Chem. Lett. 2013, 42, 689-90.

78. Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Visible light driven Ti3+ self-doped TiO2 for adsorption-photocatalysis of aqueous U(VI). Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114373.

79. Gong, X.; Tang, L.; Zou, J.; et al. Introduction of cation vacancies and iron doping into TiO2 enabling efficient uranium photoreduction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 126935.

80. Dong, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; et al. 3D structure aerogels constructed by reduced graphene oxide and hollow TiO2 spheres for efficient visible-light-driven photoreduction of U(VI) in air-equilibrated wastewater. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2021, 8, 2372-85.

81. Wan, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; et al. Boosting efficient U(VI) immobilization via synergistic Schottky heterojunction and hierarchical atomic-level injected engineering. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 133139.

82. Dong, Z.; Hu, S.; Li, Z.; et al. Biomimetic photocatalytic system designed by spatially separated cocatalysts on Z-scheme heterojunction with identified charge-transfer processes for boosting removal of U(VI). Small 2023, 19, e2300003.

83. Dong, Z.; Meng, C.; Li, Z.; et al. Novel Co3O4@TiO2@CdS@Au double-shelled nanocage for high-efficient photocatalysis removal of U(VI): roles of spatial charges separation and photothermal effect. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 452, 131248.

84. Lucena, R.; Fresno, F.; Conesa, J. C. Hydrothermally synthesized nanocrystalline tin disulphide as visible light-active photocatalyst: spectral response and stability. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 2012, 415-416, 111-7.

85. Liu, Q.; Tan, X.; Wang, S.; et al. MXene as a non-metal charge mediator in 2D layered CdS@Ti3C2 @TiO2 composites with superior Z-scheme visible light-driven photocatalytic activity. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2019, 6, 3158-69.

86. Yu, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, P.; Xiao, W.; Cheng, B. Morphology-dependent photocatalytic H2-production activity of CdS. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2014, 156-157, 184-91.

87. Zou, L.; Wang, H. R.; Wang, X. High efficient photodegradation and photocatalytic hydrogen production of CdS/BiVO4 Heterostructure through Z-scheme process. ACS. Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 303-309.

88. Chava, R. K.; Do, J. Y.; Kang, M. Enhanced photoexcited carrier separation in CdS-SnS2 heteronanostructures: a new 1D-0D visible-light photocatalytic system for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019, 7, 13614-28.

89. Zhang, K.; Fujitsuka, M.; Du, Y.; Majima, T. 2D/2D heterostructured CdS/WS2 with efficient charge separation improving H2 evolution under visible light irradiation. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018, 10, 20458-66.

90. Lin, G.; Zheng, J.; Xu, R. Template-free synthesis of uniform CdS hollow nanospheres and their photocatalytic activities. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2008, 112, 7363-70.

91. Han, Z.; Chen, G.; Li, C.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Preparation of 1D cubic Cd0.8 Zn0.2 S solid-solution nanowires using levelling effect of TGA and improved photocatalytic H2-production activity. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015, 3, 1696-702.

92. Liang, P.; Yuan, L.; Du, K.; et al. Photocatalytic reduction of uranium(VI) under visible light with 2D/1D Ti3C2/CdS. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 129831.

93. Rehman, S. U.; Wang, J.; Wu, G.; Ali, S.; Xian, J.; Mahmood, N. Unraveling the photocatalytic potential of transition metal sulfide and selenide monolayers for overall water splitting and photo-corrosion inhibition. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2024, 12, 6693-702.

94. Zhang, N.; Xing, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhou, W. Sulfur vacancy engineering of metal sulfide photocatalysts for solar energy conversion. Chem. Catalysis. 2023, 3, 100375.

95. Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Antonietti, M. Graphitic carbon nitride “reloaded”: emerging applications beyond (photo)catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 2308-26.

96. Cheng, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Fan, J.; Xiang, Q. Carbon-graphitic carbon nitride hybrids for heterogeneous photocatalysis. Small 2021, 17, e2005231.

97. Cao, S.; Low, J.; Yu, J.; Jaroniec, M. Polymeric photocatalysts based on graphitic carbon nitride. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 2150-76.

98. Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Tu, W.; Chen, G.; Xu, R. Metal-free photocatalysts for various applications in energy conversion and environmental purification. Green. Chem. 2017, 19, 882-99.

99. Bhanderi, D.; Lakhani, P.; Modi, C. K. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) as an emerging photocatalyst for sustainable environmental applications: a comprehensive review. RSC. Sustainability. 2024, 2, 265-87.

100. Wang, L.; Wang, K.; He, T.; Zhao, Y.; Song, H.; Wang, H. Graphitic carbon nitride-based photocatalytic materials: preparation strategy and application. ACS. Sustainable. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 16048-85.

101. Yu, K.; Li, Y.; Cao, X.; et al. In-situ constructing amidoxime groups on metal-free g-C3N4 to enhance chemisorption, light absorption, and carrier separation for efficient photo-assisted uranium(VI) extraction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132356.

102. Wei, W.; Luo, J.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, J. Enhancing the photocatalytic performance of g-C3N4 by using iron single-atom doping for the reduction of U(VI) in aqueous solutions. J. Solid. State. Chem. 2022, 312, 123160.

103. Zhao, J.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, R.; Han, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wu, X. Self-cleaning and regenerable nano zero-valent iron modified PCN-224 heterojunction for photo-enhanced radioactive waste reduction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 442, 130018.

104. Wang, J.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.; et al. New strategy for the persistent photocatalytic reduction of U(VI): utilization and storage of solar energy in K+ and cyano co-decorated poly(heptazine imide). Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2205542.

105. Nie, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, X.; et al. Cu doped crystalline carbon nitride with increased carrier migration efficiency for uranyl photoreduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 146908.

106. Xue, J.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.; Xie, Z.; Le, Z. Bromine doped g-C3N4 with enhanced photocatalytic reduction in U(VI). Res. Chem. Intermed. 2022, 48, 49-65.

107. Chen, T.; Li, M.; Zhou, L.; et al. Harmonizing the energy band between adsorbent and semiconductor enables efficient uranium extraction. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 127645.

108. Meng, Q.; Yang, X.; Wu, L.; et al. Metal-free 2D/2D C3N5/GO nanosheets with customized energy-level structure for radioactive nuclear wastewater treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 422, 126912.

109. Ma, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, S.; et al. Molecular engineering of multivariate porous aromatic frameworks for recovery of dispersed uranium resources. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2410778.

110. Yu, F.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Tunable perylene-based donor-acceptor conjugated microporous polymer to significantly enhance photocatalytic uranium extraction from seawater. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 412, 127558.

111. Yu, F.; Yu, S.; Li, C.; et al. Molecular engineering of biomimetic donor-acceptor conjugated microporous polymers with full-spectrum response and an unusual electronic shuttle for enhanced uranium(VI) photoreduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143285.

112. Chen, L.; Chen, B.; Kang, J.; et al. The synthesis of a novel conjugated microporous polymer and application on photocatalytic removal of uranium(VI) from wastewater under visible light. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133222.

113. Kumar, V.; Singh, V.; Kim, K.; Kwon, E. E.; Younis, S. A. Metal-organic frameworks for photocatalytic detoxification of chromium and uranium in water. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 447, 214148.