Engineering boron-terminated defects in carbon-doped boron nitride catalysts for enhanced activity in oxidative dehydrogenation of propane

Abstract

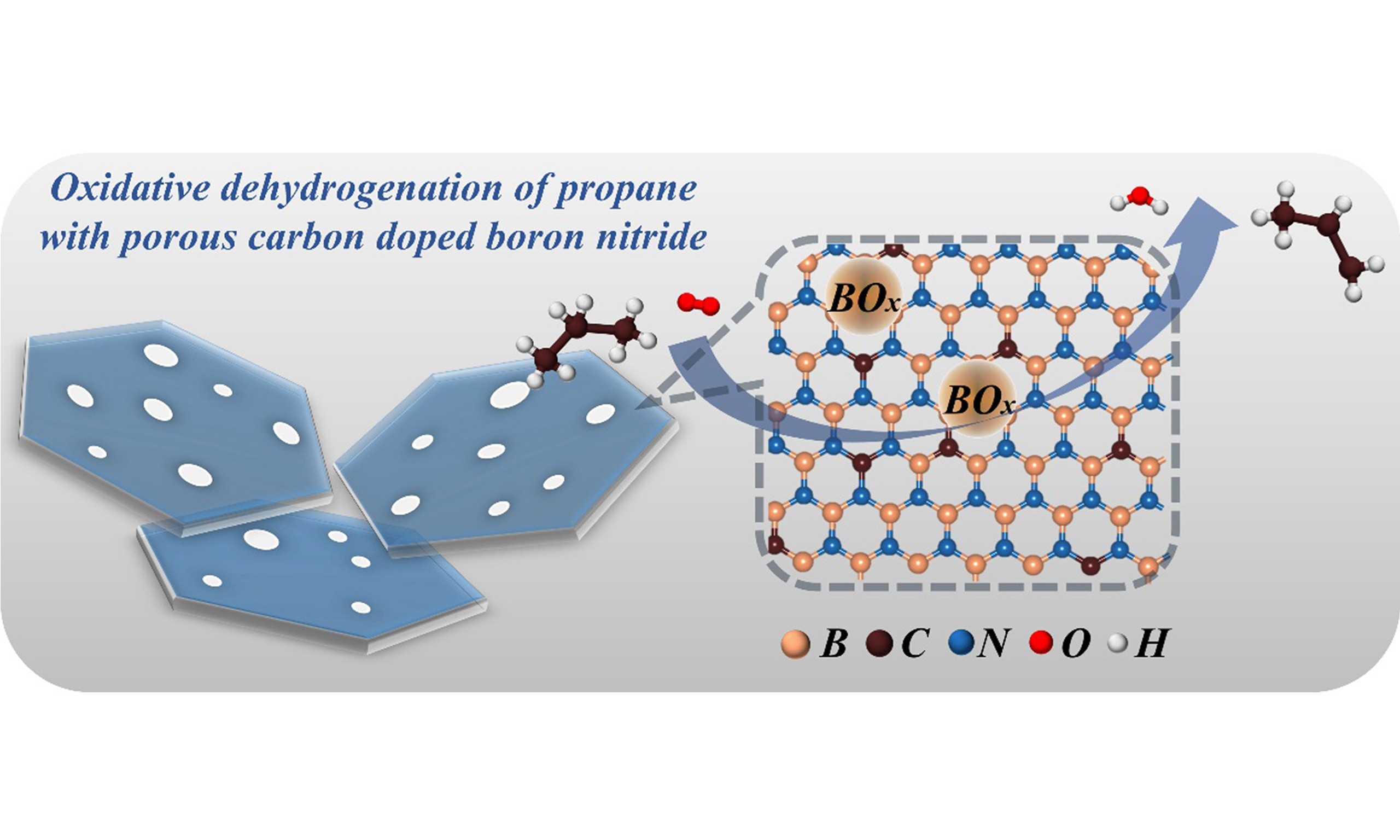

Carbon-doped boron nitride (CBN) materials are a novel class of non-metallic catalysts with significant potential in catalyzing the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane (ODHP) process. Zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8) is a type of metal-organic framework material featuring a ZIF skeleton. Boron nitride materials derived from ZIF-8 inherit its advantages, including customizable structure, tunable mesoporous properties and high specific surface area. The present work has developed a novel synthetic method to introduce and engineer the B-terminated defect in ZIF-8 derived carbon-doped boron nitride (CBN-Zx) through the co-pyrolysis of ZIF-8 and other typical precursors containing boron and nitrogen. The unique role of ZIF-8 precursors was to produce mesopores in

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Propylene is one of the most important crucial intermediate platform molecules in modern chemical industry, with a wide range of downstream products such as polypropylene, acrylic acid, propylene oxide, acrylonitrile, isopropanol and isobutylene[1,2]. The primary conventional production route for propylene synthesis is steam cracking and catalytic cracking of heavy oil, where propylene is a byproduct with low efficiency[3]. With the rapid development of shale gas industry in recent years, the development of propane dehydrogenation (PDH) route has emerged as a potential alternative to the conventional cracking route for propylene production considering the atomic and energetic economy. However, PDH reaction needs to be operated at high temperatures (> 600 °C) due to thermodynamic constraints, as well as faces catalyst sintering and coking deactivation[3-5]. In contrast, oxidative dehydrogenation of propane (ODHP) reaction attributes widespread attention due to its exothermic nature, which endows ODHP with lower reaction temperatures and reduced energy consumption[1,6-8].

Currently, research on ODHP catalysts mainly focuses on V, Cr-based metallic catalysts[9-11] and carbon materials[12] or hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN)[1,13,14] derived non-metallic catalysts. Among them, h-BN has garnered widespread attention due to its elevated olefin selectivity in ODHP reactions, high antioxidation stability and low cost[13,15,16]. h-BN has exhibited a remarkably high olefin selectivity of 91% in ODHP reactions at a 14% propane conversion[13], and subsequent extensive studies have indicated that edge boron-oxygen species, namely B–O/B–OH or boron oxygen (BOx) sites, are pivotal active sites for ODHP. The h-BN catalyzed ODHP reactions followed a unique pathway in which oxygen was activated into active radicals existing on catalyst surface and also in the gas phase, and the radicals were highly selective for

Carbon-doped boron nitride (CBN) catalysts, which are defined as the controllable doping carbon atoms or graphitic domains into the boron nitride (BN) matrixes, represent a novel type of boron-based non-metallic catalytic materials in ODHP[25-29], oxidative dehydrogenation (ODH) of ethylbenzene[30-32] and methanol conversion[33]. Carbon doping can induce and enrich defects on BN material, promoting the generation of active boron-oxygen species on the edge of the hybrid material[34]. For example, using glucose as a carbon source and thermolysis with boric acid and urea could enable the tunable content of carbon doping into the BN matrix[26]. The obtained CBN demonstrated an 18.5% propane conversion and an 82.3% selectivity towards propylene with the doping carbon content at 19.0 at.%[26]. CBN holds prominent application prospects in ODHP. Synthesizing CBN with abundant defects may be the key factor in improving its active boron-oxygen species content to enhance its catalytic performance in ODHP. CBN is typically prepared from bottom-up methods at high temperatures (> 900 °C); conventional functionalization methods (e.g., ball milling, ultrasonication, and plasma treatment) tend to complicate the preparation steps[35,36]. Consequently, achieving the selective synthesis of boron-rich edges for active boron-oxygen functionalization in CBN presents significant challenges.

The objective of this study is to synthesize CBN materials with abundant boron-rich edge defects. Zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8), a metal-organic framework (MOF) material containing ZIF skeletons, exhibits customizable structures, tunable mesoporous nature and large surface area[37,38]. The inclusion of ZIF-8 as a templating agent in the CBN precursors leads to the partial substitution of Zn for B or N atoms, disrupting the B–N bonding, ultimately resulting in the abundant defects after elimination of Zn atoms[39-41]. Herein, we propose a facile synthetic method for preparing ZIF-8 derived carbon-doped boron nitride (CBN-Zx) nanosheet materials through co-pyrolysis of ZIF-8 with boric acid and urea, and the catalytic activity and stability of this CBN-Zx catalysts are high in ODHP. Structural characterization results indicate that the introduction of ZIF-8 promotes the formation of the porous structure and high specific surface area of the CBN-Zx material. Additionally, the prepared CBN-Zx material generates abundant boron-rich edges indicative by the B/N value from X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) analysis and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) result. Consequently, the optimal CBN-Z0.4 catalyst demonstrates high activity in ODHP, which is 3.7 times higher than that of pristine h-BN (propane conversion of 23.9% vs. 6.5%), outperforming most boron-based catalysts in ODHP. Abundant B-terminated defects would slowly transform into active BOx species during the reaction, which may be the primary reason for the high activity and selectivity of the synthesized catalyst in ODHP reaction. This study provides a valuable reference for the design and preparation of B-rich sites of CBN catalysts shedding light on their potential practical applications in ODHP reaction.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (metal basis, 99.0%), urea (99.0%) and deionized water (conductivity, σ ≤

Preparation of CBN and CBN-Zx

First, 1.6 g 2-methylimidazole was dissolved in 30 mL deionized water and was continuously stirred at room temperature. Simultaneously, 3.0 g zinc nitrate hexahydrate was added into 30 mL deionized water in a separate vessel and stirred until fully dissolved. The aqueous solution of zinc nitrate was slowly added into the solution of 2-methylimidazole with constant agitation. Over approximately 6 h, the color of the mixture transferred from clear to white with the formation of suspension. The resulting precipitate was separated by centrifugation and was washed with deionized water three times to remove impurities. The resulting white precipitate was then dried overnight at 80 °C yielding a white solid powder, which was denoted as ZIF-8.

The CBN-Zx (x = 0.2, 0.4 g) catalysts were prepared via co-pyrolysis of boric acid, urea and ZIF-8. In a typical synthetic approach, 0.6 g boric acid and 6.1 g urea were dissolved in 40 mL deionized water. Subsequently, a certain amount of (0.2 or 0.4 g) ZIF-8 was added into the solution, and the mixture was stirred at 80 °C to evaporate water. The resulting white crystalline powder was then annealed at 950 °C for

Characterizations of the catalysts

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained using a Bruker D8 ADVANCE diffractometer equipped with a rotating anode using Cu Kα radiation (40 kV, 40 mA) in the 2θ range of 10°-90° with a scan rate of 10° min-1. The XPS analysis was performed on an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) ESCALAB 250, and the data was acquired by a monochromatized Al Kα X-ray source. The binding energies were referenced to the C 1s peak of environmental carbon at 284.6 eV. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was recorded on a FEI Tecnai G2 T12 microscope with an accelerating voltage of 120 kV. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) was employed for FEI Nova NanoSEM 450. N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were acquired with a Micrometrics ASAP 2020 instrument, following a degassing process at 120 °C for 12 h under vacuum conditions. The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) experiments were performed in a TG-DSC NETZSCH STA 449 F3 instrument. The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was conducted with a Thermo Nicolet iS10 ATR-FTIR system. The ultraviolet-visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-Vis DRS) was performed on the UV-2450 spectrophotometer. The spectra were recorded in the 400-4,000 cm-1 range with 32 scans at a resolution of 4 cm-1. The EPR was obtained from an ESR5000 EPR spectrometer (Germany).

Activity evaluation of the catalysts in oxidative dehydrogenation of propane

The ODHP reaction was performed in a fixed bed quartz tube reactor with a 10 mm outside diameter, which operated in plug flow mode. First, 100 mg catalyst was mounted into the middle of the reactor (thermostatic heating zone) with a certain amount of quartz wool as cover and holder at the top and bottom of the catalyst powder to keep the same gas hour space velocity (GHSV). The reactant mixture contained

The capital letters N and F represent the number of carbon atoms in a reactant or product and the flow rate (input or output) of each component, respectively. The lower letter (including p, i) represents the product and count symbol. The carbon balance of the reaction system with all catalysts is 100% ± 5%.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Morphology and chemical structure characterizations of the catalysts

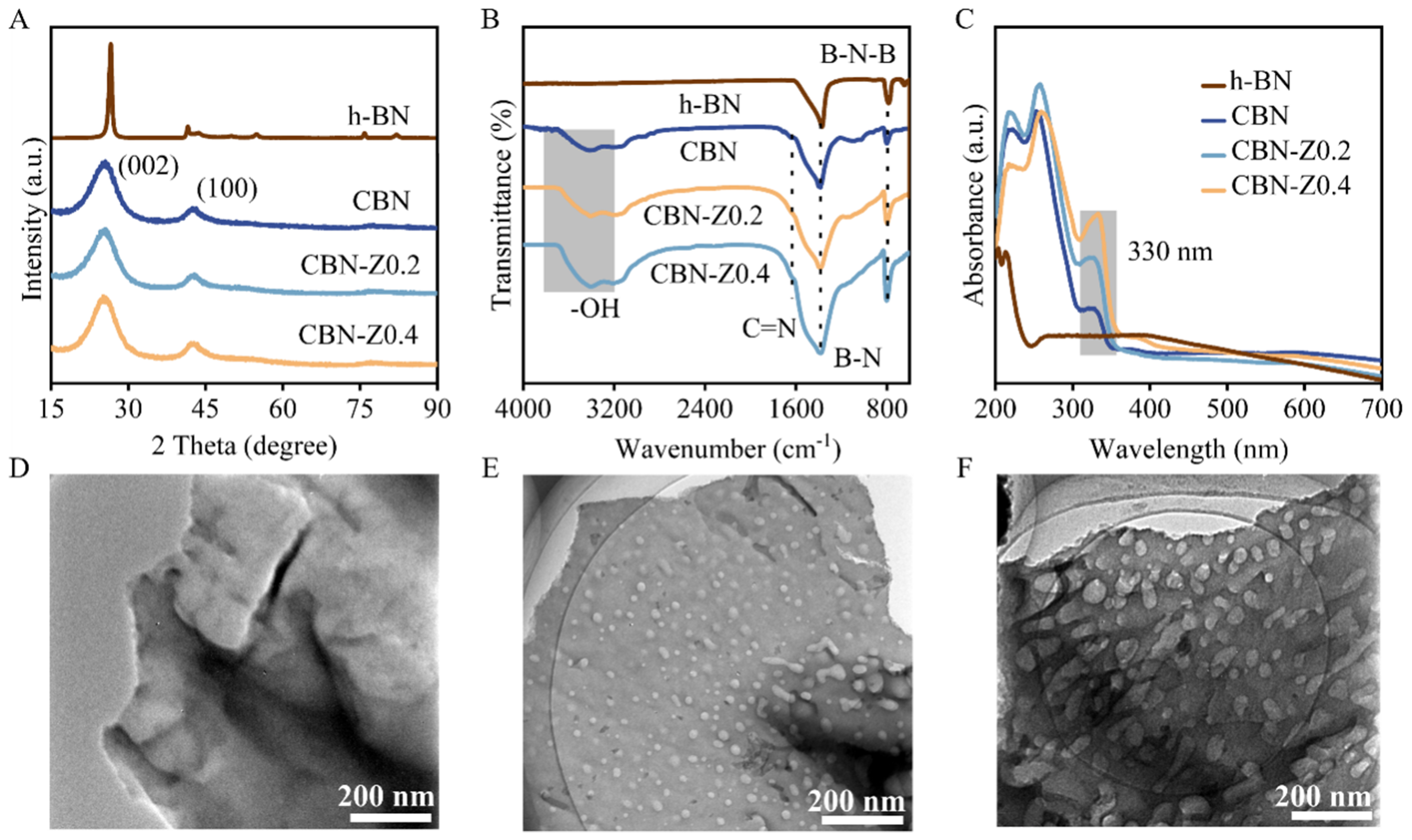

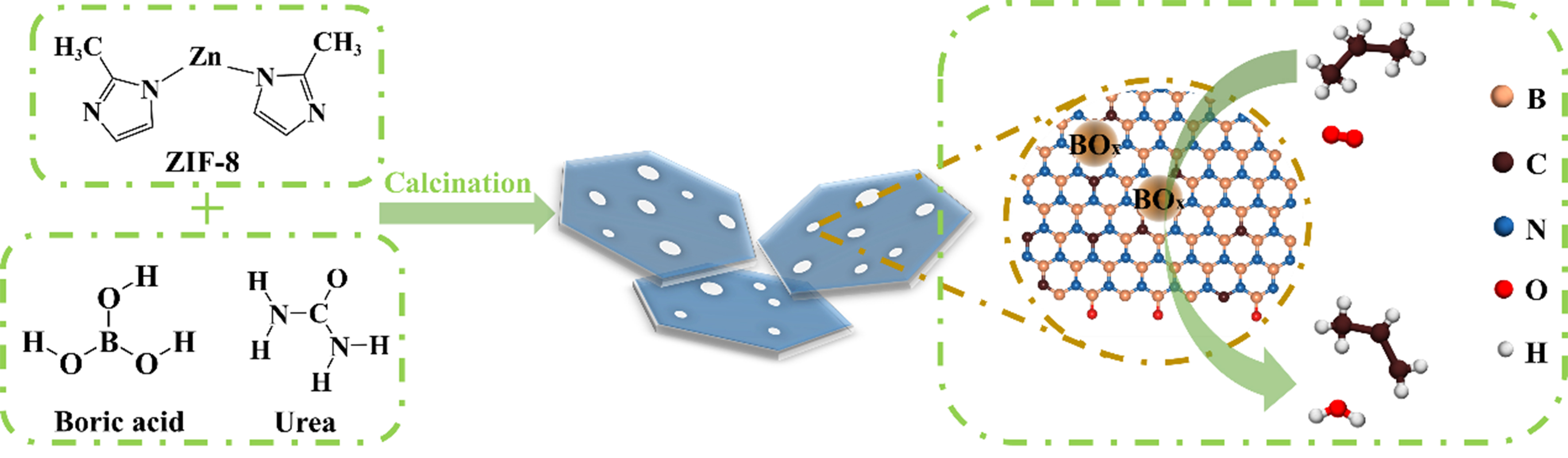

Scheme 1 depicted the synthetic procedure for porous CBN-Zx via a pyrolysis strategy with boric acid, urea and ZIF-8 precursors, and the details could be found in the experimental section. Specifically, different amounts of ZIF-8 were added to a solution of boric acid and urea, followed by recrystallization and calcination to yield CBN-Zx nanosheets, which could then be applied directly in ODHP reaction. For comparison, CBN was also prepared using the same method, except for the absence of ZIF-8. To elucidate the crystal phase and chemical structure of the commercial h-BN and the as-prepared CBN and CBN-Zx catalysts, XRD, FTIR and UV-Vis DRS measurements were performed. The XRD patterns [Figure 1A] showed that all catalysts exhibited two broad reflections at around 26.0° and 43.6°, which could be assigned as the (002) and (100) crystal planes of the layered borocarbonitride (BCN) structure, respectively[26,28]. Commercial h-BN exhibited higher crystallinity [Figure 1A] than the prepared CBN-Zx or CBN catalysts. FTIR spectra [Figure 1B] of CBN, CBN-Z0.2 and CBN-Z0.4 exhibited two prominent adsorptions at 803 and 1,390 cm-1, corresponding to the out-of-plane bending vibration and in-plane transverse stretching vibration of B–N–B and B–N, respectively[42] and another absorption bond at around 1,600 cm-1 was attributed to C=N bond vibration, which confirmed the ternary hybrid system of B, C and N elements in the synthesized materials[26]. In comparison, only B–N and B–N–B vibrational mode peaks could be observed in the FTIR spectra in commercial h-BN catalyst [Figure 1B]. The FTIR spectra of ZIF-8 and CBN-Z0.4 precursors were also provided in Supplementary Figure 1. Several prominent peaks of ZIF-8 reflected the ordered coordination structure of Zn-2-MeIm (Zn-N nodes) and the formation of repetitive units, confirming the successful synthesis of ZIF-8 [Supplementary Figure 1A][43,44], and the FTIR spectra of the precursor for CBN-Z0.4 showed features that correspond to boric acid and urea [Supplementary Figure 1B][45]. In the UV-Vis DRS [Figure 1C], the characteristic peaks at 219 and 257 nm were attributed to the σ and unpaired electron transitions in BN, respectively[28]. Additionally, the band at 330 nm corresponded to the formation of C–N bonds or the weak π interactions of sp2 hybridized C=C[46,47]. No absorption signal between 330 nm was observed for h-BN. The UV-Vis DRS result was consistent with the FTIR spectra, showing that C has been doped into BN structure.

Figure 1. (A) XRD patterns, (B) FTIR spectra, (C) UV-Vis DRS of h-BN, CBN and CBN-Zx catalysts. TEM images of (D) CBN, (E) CBN-Z0.2 and (F) CBN-Z0.4, respectively. XRD: X-ray diffraction; FTIR: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy; UV-Vis DRS: ultraviolet-visible diffuse reflectance spectra; h-BN: hexagonal boron nitride; CBN: carbon-doped boron nitride; CBN-Zx: ZIF-8 derived carbon-doped boron nitride; TEM: transmission electron microscope.

Scheme 1. Schematic illustration of CBN-Zx synthesis and the ODHP reaction on CBN-Zx catalysts. CBN-Zx: ZIF-8 derived carbon-doped boron nitride; ODHP: oxidative dehydrogenation of propane.

The morphologies of CBN and CBN-Zx catalysts were characterized through TEM and SEM measurements. Figure 1D-F and Supplementary Figure 2A-C revealed that the CBN, CBN-Z0.2 and CBN-Z0.4 catalysts exhibited a similar nanosheet-like structure. Notably, pores with different sizes were observed in CBN-Z0.2 [Figure 1E] and CBN-Z0.4 [Figure 1F] compared with CBN showing no obvious pore structure [Figure 1D]. Nanosheets with porous structure could expose additional active sites and may exhibit high mass transfer efficiency[48]. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping of selected areas [Supplementary Figure 3] confirmed the presence and uniform distribution of B, N, C, and O elements in CBN-Z0.4 catalyst. Additionally, commercial h-BN exhibited a stacked nanosheet-like morphology

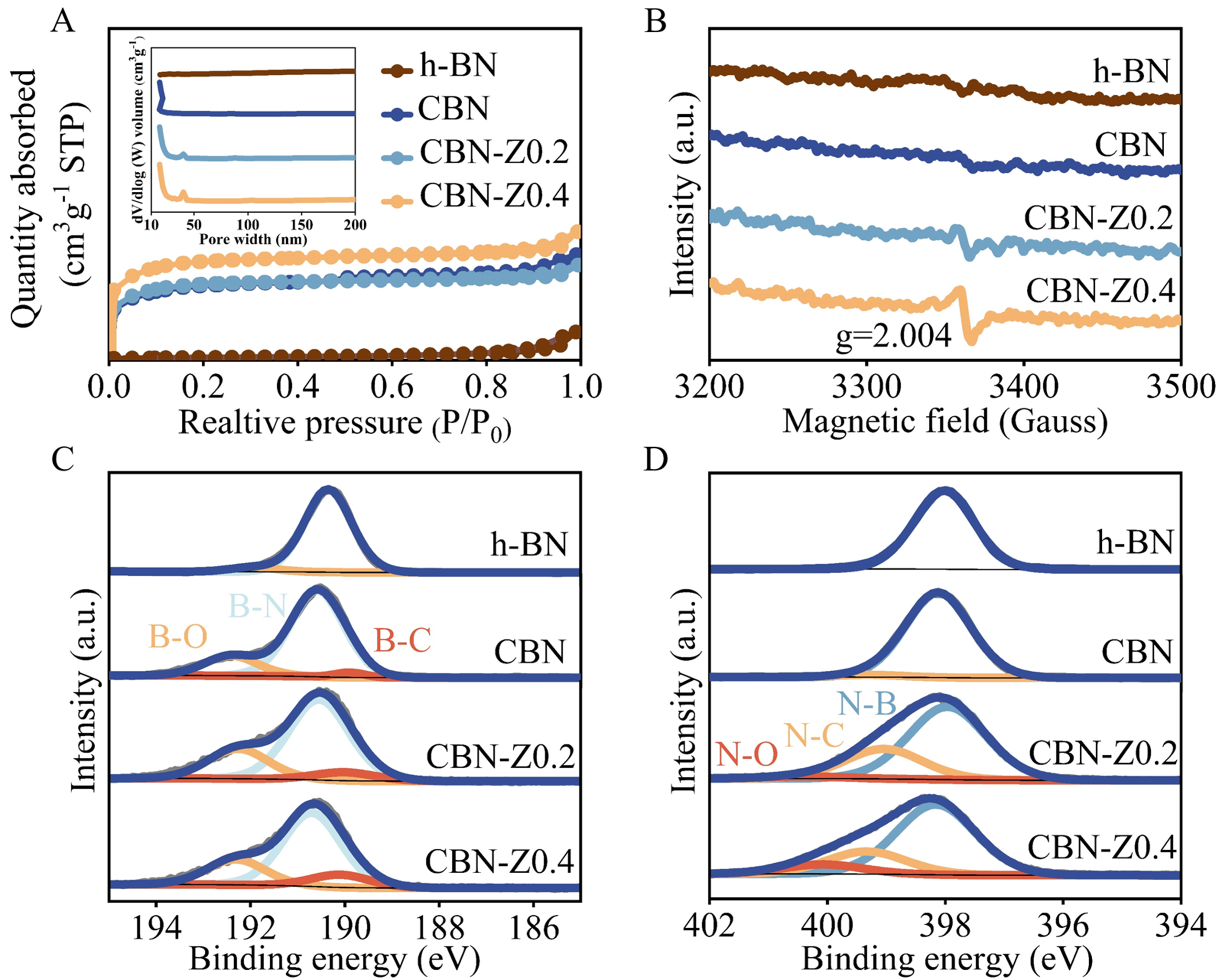

N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and pore size distribution [Figure 2A] were also investigated to clarify the specific surface area and porosity of catalysts. The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of h-BN, CBN, CBN-Z0.2 and CBN-Z0.4 samples exhibited type IV isotherms with H4-type hysteresis loops, indicating the co-existence of mesopores and micropores. As shown in Table 1, the specific surface area of CBN-Z0.4 was determined at 1,302.4 m2·g-1, significantly higher than that of CBN-Z0.2 (1,003.6 m2·g-1), CBN (995.1 m2·g-1) and h-BN (42.1 m2·g-1). As shown in Figure 2A, the pore size of CBN was predominantly distributed in the range of 8-10 nm, while CBN-Z0.2 and CBN-Z0.4 catalysts exhibited pore sizes in the range of 30-40 nm indicating the presence of a mesoporous structure with larger pores, which was consistent the TEM results

Figure 2. (A) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and pore size distributions; (B) EPR spectra; Deconvolution of XPS spectra (C) B 1s and (D) N 1s of h-BN, CBN and CBN-Zx. EPR: Electron paramagnetic resonance; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectra; h-BN: hexagonal boron nitride; CBN: carbon-doped boron nitride; CBN-Zx: ZIF-8 derived carbon-doped boron nitride.

Specific surface area and XPS results for h-BN, CBN and CBN-Zx catalysts

| Catalysts | SBET (m2·g-1) | Content (at.%) | B/Na | |||

| B | N | C | O | |||

| h-BN | 42.1 | 49.9 | 40.7 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 1.23 |

| CBN | 995.1 | 43.1 | 33.8 | 10.2 | 12.8 | 1.27 |

| CBN-Z0.2 | 1,003.6 | 43.0 | 33.1 | 10.3 | 13.6 | 1.30 |

| CBN-Z0.4 | 1,302.2 | 43.4 | 30.0 | 13.4 | 13.1 | 1.45 |

EPR analysis could identify unpaired electrons and characterize surface defects, which was employed to examine the defects in h-BN and our synthesized samples (CBN and CBN-Zx). As depicted in Figure 2B, a significant increase in EPR intensity at a g value of 2.004 was observed in CBN-Z0.2 and CBN-Z0.4 catalysts compared with CBN and h-BN catalysts. This enhancement of EPR signal confirmed that the presence of N vacancies (B-terminated defects) within the lattice of the material resulted in unpaired electrons, generated free radicals and subsequently led to the appearance of magnetic resonance signals in the EPR spectrum for the CBN-Z0.2 and CBN-Z0.4 catalysts[24,49].

XPS spectra were measured to reflect the surface element composition and electronic structure of CBN and CBN-Zx catalysts. The XPS survey spectra [Supplementary Figure 5A] demonstrated that B, N, C and O were four main elements in all the synthesized catalysts, and no Zn species were observed [Supplementary Figure 5B], indicating that all Zn species have volatilized during the high-temperature pyrolysis process (boiling point of Zn is 900 °C[50]). The elemental contents obtained from XPS analysis were summarized in Table 1. The C content in the catalysts increased from 10.2 at.% to 13.4 at.%, while the N content decreased from

XPS results of CBN and CBN-Zx catalysts before and after ODHP reactions

| Catalysts | O content (at.%) | B–O content (at.%) | BOx content (at.%) |

| Fresh CBN | 12.8 | 8.1 | - |

| Fresh CBN-Z0.2 | 13.6 | 10.4 | - |

| Fresh CBN-Z0.4 | 13.1 | 9.9 | - |

| Used CBN | 15.2 | 10.2 | 1.4 |

| Used CBN-Z0.2 | 24.4 | 8.4 | 11.0 |

| Used CBN-Z0.4 | 27.1 | 8.6 | 11.5 |

Performance of CBN-Zx catalysts in ODHP reaction

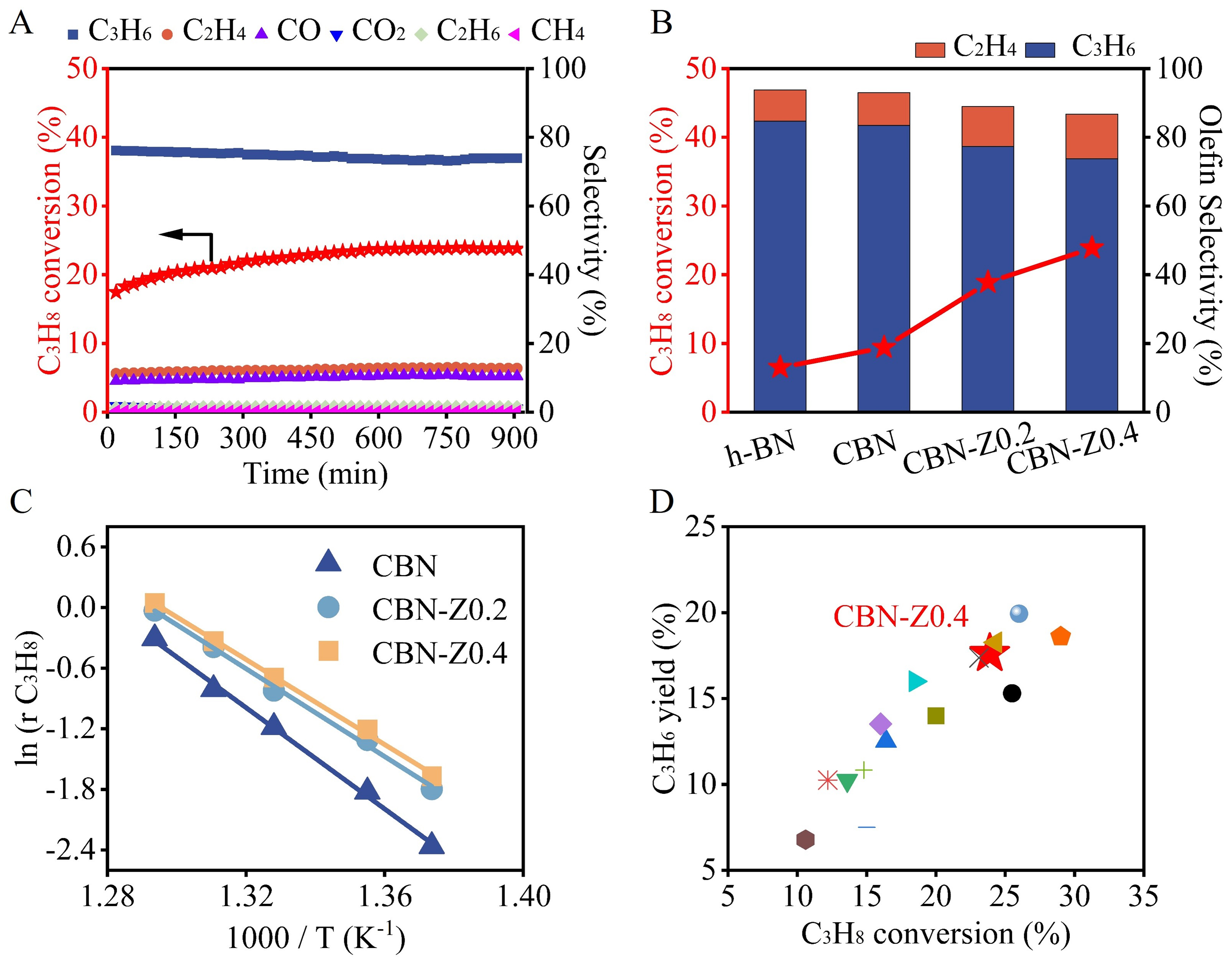

The catalytic performance of h-BN, CBN, CBN-Z0.2, and CBN-Z0.4 catalysts in ODHP was evaluated. The ODHP reaction was performed under relatively gentle reaction conditions at 500 °C with the total flow rate of 25 mL·min-1, eliminating diffusion limitations. In a typical blank experiment (without catalyst), the system showed a negligible ODHP reaction activity with propane conversion of 0.5% [Supplementary Figure 8]. As shown in Figure 3A, CBN-Z0.4 demonstrated an initial propane conversion of 18.0% and culminated in a maximum propane conversion of 23.9% after 400 min, and the main reaction products were propylene (73.5%), ethene (12.9%) and CO (10.8%) with slight ethane (1.5%), methane (0.2%) and CO2 (1.1%). The catalytic performance could keep stable for over 900 min without obvious deactivation, suggesting its relatively high stability. It could be observed that CBN-Z0.4 demonstrated an obvious induction period in the ODHP reaction. Similar induction period could also be observed in the ODHP reaction over CBN-Z0.2 catalyst [Supplementary Figure 9] due to their similar structure. This phenomenon was related to the unique structure of CBN-Z0.4 and CBN-Z0.2 with abundant B-terminated pores or defects as shown above, which may be slowly activated into BOx active sites during the reaction, leading to the induction period. However, h-BN did not exhibit the induction period [Supplementary Figure 10]. Supplementary Figure 11 displayed the SEM images of the used CBN-Z0.2 and CBN-Z0.4 catalysts, showing that the nanosheet structure remained after the reaction, also suggesting the relatively high stability of these materials.

Figure 3. (A) Time on stream of CBN-Z0.4 in ODHP reactions; (B) Catalytic performance of h-BN, CBN and CBN-Zx in ODHP reactions; (C) Arrhenius plots and Ea values of CBN and CBN-Zx; (D) Propylene yield as a function of propane conversion over several typical

As shown in Figure 3B, the proposed CBN-Z0.2 and CBN-Z0.4 catalysts exhibited superior catalytic performance in the ODHP reaction compared with commercial h-BN and the synthesized CBN catalysts. CBN-Z0.4 demonstrated a high propane conversion of 23.9%, which was about 2.5 times (23.9% vs. 9.4%) higher than that on CBN. Notably, a high total olefin selectivity of 86.4% on CBN-Z0.4 was maintained even under a high conversion of 23.9%. The obtained CBN-Z0.4 catalyst exhibited a propylene production rate of 0.52 gC3H6·gCat-1·h-1 at 500 °C, which was higher than other catalysts [Supplementary Table 1]. Furthermore, the propane conversion significantly increased for all catalysts at 510 °C, with the CBN-Z0.4 catalyst maintaining the highest propylene production rate (0.66 gC3H6·gCat-1·h-1). As shown in Figure 3C, the apparent activation energy (Ea) for ODHP was determined as 208.0, 180.6 and 174.9 kJ·mol-1 for CBN, CBN-Z0.2 and CBN-Z0.4, respectively, according to the Arrhenius equation, which was lower than that on h-BN (220-

Physical-chemical nature behind the high ODHP activity of CBN-Zx catalysts

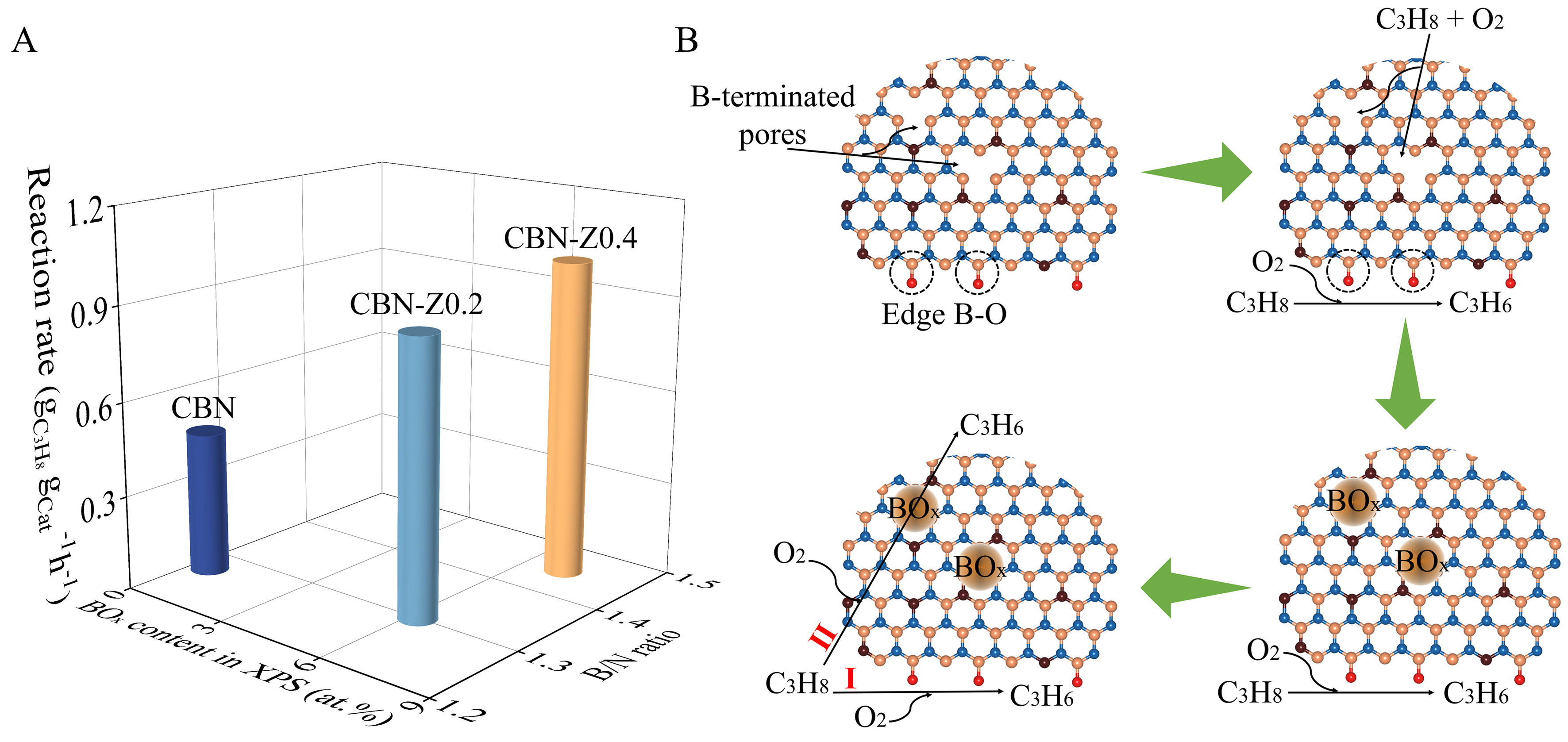

The detailed physical-chemical nature behind the high activity of CBN-Zx catalysts in ODHP reaction was unraveled in this part by linking the structural characterization and the catalytic activity evaluation results. As shown in Table 2, the used CBN-Z0.4 catalyst demonstrated the highest O content of 27.1 at.% among all the other catalysts, and also showed an obvious increase compared with fresh CBN-Z0.4 catalyst (13.1 at.%). The used CBN-Z0.2 catalyst exhibited a similar increasing trend of oxygen content after ODHP reaction from 13.6 at.% to 24.4 at.%. This was consistent with above observations and hypothesis of induction period. On the contrary, the surface O content of the used CBN catalyst showed a negligible increase after ODHP. These O content XPS analysis results demonstrated that carbon doping with ZIF-8 facilitated the O atom incorporation into the edge of the BN matrix, especially under ODHP reaction conditions.

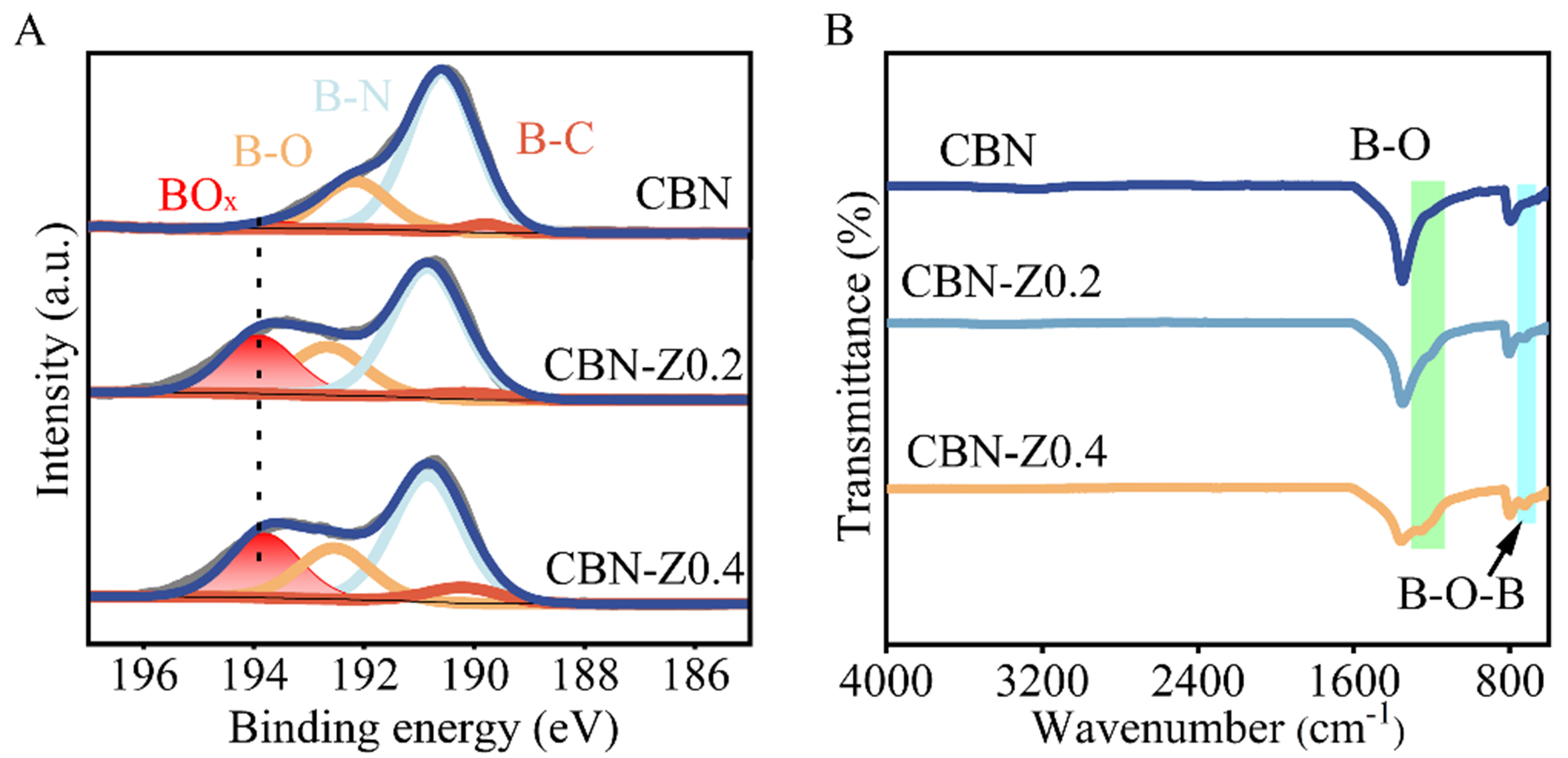

Figure 4A showed the deconvolution of B 1s XPS spectra of the used CBN, CBN-Z0.2 and CBN-Z0.4 catalysts, and the peak-fitting results and corresponding surface chemical composition were summarized in Table 2. Compared with fresh catalysts, a new signal corresponding to BOx species was found at 193.7 eV for all used catalysts[26,28,54]. The used CBN-Z0.2 and CBN-Z0.4 catalysts exhibited higher BOx content, at

Figure 4. (A) Deconvolution of B 1s XPS spectra and (B) FTIR spectra of the used CBN and CBN-Zx. XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectra; FTIR: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy; CBN: carbon-doped boron nitride; CBN-Zx: ZIF-8 derived carbon-doped boron nitride.

Figure 5. (A) Correlation between the B/N ratio, BOx content obtained from XPS and the reaction rate of CBN and CBN-Zx in ODHP; (B) The schematic diagram of BOx species generation from B-terminated defects in ODHP. BOx: Boron oxygen; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectra; CBN: carbon-doped boron nitride; CBN-Zx: ZIF-8 derived carbon-doped boron nitride; ODHP: oxidative dehydrogenation of propane.

Based on the results presented above, the ODHP on CBN-Zx catalysts could be elucidated as shown in Figure 5B. Two types of B–O species included B–O sites at the edge of CBN (type I) and BOx species formed at B-terminated defects (type II), which all contributed to ODHP reactions. The reason for the high activity of CBN-Zx catalysts could be attributed to their unique structure, which contained plenty of B-terminated defects resulting from the volatilization of Zn and C species during the pyrolysis of ZIF-8 containing precursors. These B-terminated defects transformed into active BOx species[24], and eventually promoted the conversion of propane, showing relatively high activity in the ODHP process.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we have developed a novel co-pyrolysis method for the synthesis of CBN catalysts via ZIF-8 as part of the precursors. The unique role of ZIF-8 could introduce plenty of B-terminated defects into CBN catalysts, and these defects could transform into BOx active species under reaction conditions, and thus enhanced the catalytic activity of the synthesized CBN catalysts. The optimized non-metallic CBN-0.4 catalyst exhibited a propane conversion at 23.9% and with the olefin selectivity at 86.4% at 500 °C, which outperformed h-BN and most boron-based catalysts. The present study provides a new idea for designing and synthesizing highly efficient boron-based catalysts for ODHP reactions, and the structure-function relations in the present work may also shed light on development of other non-metallic catalysts from MOFs.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the idea of the project: Gao, Z.; Qi, W.

Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, performed data analysis and interpretation, and wrote the draft of the manuscript: Sun, G.; Dai, X.

Performed data acquisition and provided administrative, technical, and material support: Zeng, X.; Bai, Y.

Finalized the manuscript: Qi, W.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the NSFC of China (22072163, U23A20545), the Shccig-Qinling Program, the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province of China (2020-YQ-02) and the China Baowu Low Carbon Metallurgy Innovation Foudation BWLCF202113.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Sheng, J.; Yan, B.; Lu, W. D.; et al. Oxidative dehydrogenation of light alkanes to olefins on metal-free catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 1438-68.

2. Fu, Z.; Li, D.; Zhou, L.; et al. A mini review on oxidative dehydrogenation of propane over boron nitride catalysts. Petrol. Sci. 2023, 20, 2488-98.

3. Carter, J. H.; Bere, T.; Pitchers, J. R.; et al. Direct and oxidative dehydrogenation of propane: from catalyst design to industrial application. Green. Chem. 2021, 23, 9747-99.

4. Chen, S.; Chang, X.; Sun, G.; et al. Propane dehydrogenation: catalyst development, new chemistry, and emerging technologies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 3315-54.

5. Sun, M.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H.; Suo, Y.; Yuan, Z. Design strategies of stable catalysts for propane dehydrogenation to propylene. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 4719-41.

6. Jiang, X.; Sharma, L.; Fung, V.; et al. Oxidative dehydrogenation of propane to propylene with soft oxidants via heterogeneous catalysis. ACS. Catal. 2021, 11, 2182-234.

7. Jiang, X.; Zhang, K.; Forte, M. J.; Cao, S.; Hanna, B. S.; Wu, Z. Recent advances in oxidative dehydrogenation of propane to propylene on boron-based catalysts. Catal. Rev. 2022, 1-80.

8. Dai, X.; Qi, W. Novel alkane dehydrogenation routes via tailored catalysts. ChemCatChem 2024, e202400410.

9. Mesa JA, Robijns S, Khan IA, Rigamonti MG, Bols ML, Dusselier M. Support effects in vanadium incipient wetness impregnation for oxidative and non-oxidative propane dehydrogenation catalysis. Catal. Today. 2024, 430, 114546.

10. Carrero, C. A.; Schloegl, R.; Wachs, I. E.; Schomaecker, R. Critical literature review of the kinetics for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane over well-defined supported vanadium oxide catalysts. ACS. Catal. 2014, 4, 3357-80.

11. Monguen CK, El Kasmi A, Arshad MF, Kouotou PM, Daniel S, Tian Z. Oxidative dehydrogenation of propane into propene over chromium oxides. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 4546-60.

12. Cao, T.; Dai, X.; Liu, W.; Fu, Y.; Qi, W. Carbon nanotubes modified by multi-heteroatoms polymer for oxidative dehydrogenation of propane: improvement of propene selectivity and oxidation resistance. Carbon 2022, 189, 199-209.

13. Grant, J. T.; Carrero, C. A.; Goeltl, F.; et al. Selective oxidative dehydrogenation of propane to propene using boron nitride catalysts. Science 2016, 354, 1570-3.

14. Auwärter, W. Hexagonal boron nitride monolayers on metal supports: Versatile templates for atoms, molecules and nanostructures. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2019, 74, 1-95.

15. Naclerio, A. E.; Kidambi, P. R. A review of scalable hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) synthesis for present and future applications. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2207374.

16. Angizi, S.; Alem, S. A. A.; Hasanzadeh, A. M.; et al. A comprehensive review on planar boron nitride nanomaterials: from 2D nanosheets towards 0D quantum dots. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 124, 100884.

17. Shi, L.; Wang, D.; Song, W.; Shao, D.; Zhang, W.; Lu, A. Edge-hydroxylated boron nitride for oxidative dehydrogenation of propane to propylene. ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 1788-93.

18. Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Wu, P.; et al. O2 activation and oxidative dehydrogenation of propane on hexagonal boron nitride: mechanism revisited. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019, 123, 2256-66.

19. Venegas, J. M.; Hermans, I. The influence of reactor parameters on the boron nitride-catalyzed oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Org. Process. Res. Dev. 2018, 22, 1644-52.

20. Zhang, Z.; Tian, J.; Wu, X.; et al. Unraveling radical and oxygenate routes in the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane over boron nitride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 7910-7.

21. Zhang, X.; You, R.; Wei, Z.; et al. Radical chemistry and reaction mechanisms of propane oxidative dehydrogenation over hexagonal boron nitride catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 8042-6.

22. Lin, Y.; Williams, T. V.; Xu, T.; Cao, W.; Elsayed-ali, H. E.; Connell, J. W. Aqueous dispersions of few-layered and monolayered hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets from sonication-assisted hydrolysis: critical role of water. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2011, 115, 2679-85.

23. Chen, H.; Yang, Z.; Guo, W.; et al. From highly purified boron nitride to boron nitride-based heterostructures: an inorganic precursor-based strategy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1906284.

24. Liu, Z.; Yan, B.; Meng, S.; et al. Plasma tuning local environment of hexagonal boron nitride for oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 19691-5.

25. Guo, F.; Yang, P.; Pan, Z.; Cao, X. N.; Xie, Z.; Wang, X. Carbon-doped BN nanosheets for the oxidative dehydrogenation of ethylbenzene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 8231-5.

26. Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Y.; Huang, X.; Xie, Z. New insight into structural transformations of borocarbonitride in oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 2021, 628, 118402.

27. Li, D.; Bi, J.; Xie, Z.; et al. Flour-derived borocarbonitride enriched with boron–oxygen species for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane to olefins. Sci. China. Chem. 2023, 66, 2389-99.

28. Wang, G.; Chen, S.; Duan, Q.; Wei, F.; Lin, S.; Xie, Z. Surface chemistry and catalytic reactivity of borocarbonitride in oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202307470.

29. Wang, G.; Hu, A.; Duan, Q.; et al. Hierarchical boroncarbonitride nanosheets as metal-free catalysts for enhanced oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 288, 119848.

30. Han, R.; Diao, J.; Kumar, S.; et al. Boron nitride for enhanced oxidative dehydrogenation of ethylbenzene. J. Energy. Chem. 2021, 57, 477-84.

31. Sheng, J.; Yan, B.; He, B.; Lu, W.; Li, W.; Lu, A. Nonmetallic boron nitride embedded graphitic carbon catalyst for oxidative dehydrogenation of ethylbenzene. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 1809-15.

32. Zhang, X.; Dai, X.; Wu, K.; et al. A generalized approach to adjust the catalytic activity of borocarbonitride for alkane oxidative dehydrogenation reactions. J. Catal. 2022, 405, 105-15.

33. Zhang, X.; Yan, P.; Xu, J.; et al. Methanol conversion on borocarbonitride catalysts: Identification and quantification of active sites. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba5778.

34. Nehate, S.; Saikumar, A.; Prakash, A.; Sundaram, K. A review of boron carbon nitride thin films and progress in nanomaterials. Mater. Today. Adv. 2020, 8, 100106.

35. Manzar, R.; Saeed, M.; Shahzad, U.; et al. Recent advancements in boron carbon nitride (BNC) nanoscale materials for efficient supercapacitor performances. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 144, 101286.

36. Namba, S.; Takagaki, A.; Jimura, K.; Hayashi, S.; Kikuchi, R.; Ted, O. S. Effects of ball-milling treatment on physicochemical properties and solid base activity of hexagonal boron nitrides. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 302-9.

37. Mo, Z.; Tai, D.; Zhang, H.; Shahab, A. A comprehensive review on the adsorption of heavy metals by zeolite imidazole framework (ZIF-8) based nanocomposite in water. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 443, 136320.

38. Dai, H.; Yuan, X.; Jiang, L.; et al. Recent advances on ZIF-8 composites for adsorption and photocatalytic wastewater pollutant removal: fabrication, applications and perspective. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 441, 213985.

39. Wu, P.; Yang, S.; Zhu, W.; et al. Tailoring N-terminated defective edges of porous boron nitride for enhanced aerobic catalysis. Small 2017, 13, 1701857.

40. Yang, S.; Zhang, F.; Qiu, H.; et al. Highly efficient hydrogen production from methanol by single nickel atoms anchored on defective boron nitride nanosheet. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 8800-8.

41. Chao, Y.; Tang, B.; Luo, J.; et al. Hierarchical porous boron nitride with boron vacancies for improved adsorption performance to antibiotics. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2021, 584, 154-63.

42. Wang, T.; Yin, J.; Guo, X.; Chen, Y.; Lang, W.; Guo, Y. Modulating the crystallinity of boron nitride for propane oxidative dehydrogenation. J. Catal. 2021, 393, 149-58.

43. Cao, T.; Dai, X.; Fu, Y.; Qi, W. Coordination polymer-derived non-precious metal catalyst for propane dehydrogenation: Highly dispersed zinc anchored on N-doped carbon. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 607, 155055.

44. Li, L.; Bai, X.; Shao, L.; et al. Fabrication of a MOF/aerogel composite via a mild and green one-pot method. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 94, 2477-83.

45. Gross, P.; Höppe, H. A. Unravelling the urea-route to boron nitride: synthesis and characterization of the crucial reaction intermediate ammonium bis(biureto)borate. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 8052-61.

46. Lu, L.; He, J.; Wu, P.; et al. Taming electronic properties of boron nitride nanosheets as metal-free catalysts for aerobic oxidative desulfurization of fuels. Green. Chem. 2018, 20, 4453-60.

47. Xiong, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, H.; et al. Carbon-doped porous boron nitride: metal-free adsorbents for sulfur removal from fuels. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015, 3, 12738-47.

48. Qian, H.; Sun, F.; Zhang, W.; Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Fang, K. Efficient metal borate catalysts for oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 1996-2005.

49. Lei, Y.; Pakhira, S.; Fujisawa, K.; et al. Low temperature activation of inert hexagonal boron nitride for metal deposition and single atom catalysis. Mater. Today. 2021, 51, 108-16.

50. Mu, L.; Luo, J.; Wang, C.; et al. BN/ZIF-8 derived carbon hybrid materials for adsorptive desulfurization: Insights into adsorptive property and reaction kinetics. Fuel 2021, 288, 119685.

51. Li, X.; Lin, B.; Li, H.; et al. Carbon doped hexagonal BN as a highly efficient metal-free base catalyst for Knoevenagel condensation reaction. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2018, 239, 254-9.

52. Wang, G.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X.; Xie, Z. Three-dimensional porous hexagonal boron nitride fibers as metal-free catalysts with enhanced catalytic activity for oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 17949-58.

53. Liu, Q.; Chen, C.; Liu, Q.; et al. Nonmetal oxygen vacancies confined under boron nitride for enhanced oxidative dehydrogenation of propane to propene. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 537, 147927.

54. Kiss, J.; Révész, K.; Solymosi, F. Segregation of boron and its reaction with oxygen on Rh. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1989, 37, 95-110.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].