Contribution of metal-hydride species on the catalysts to catalytic performances

Abstract

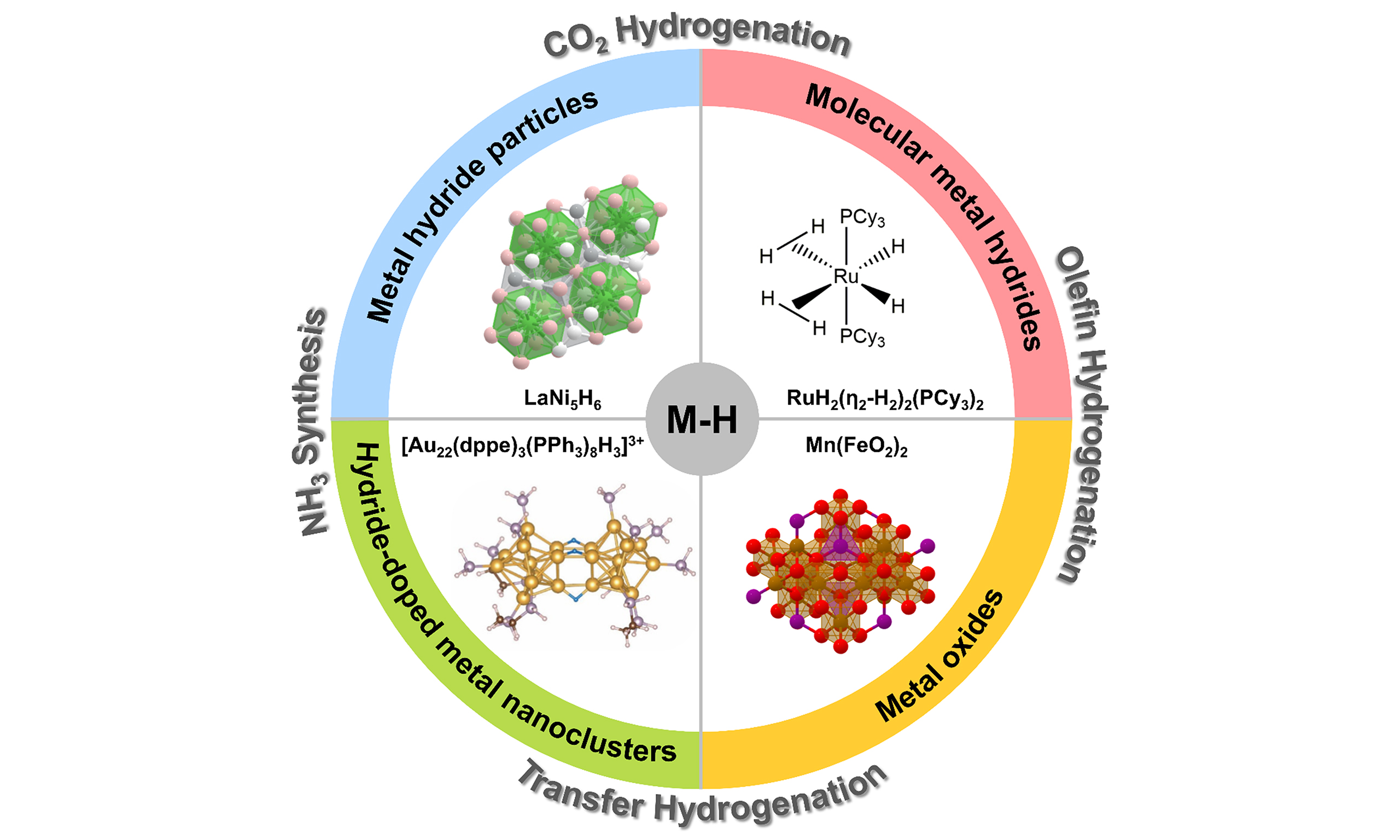

Metal-hydride (M-H) species typically exhibit high reactivities and distinctive chemical properties, which have prompted extensive investigations within the field of catalysis. Metal hydrides possess abundant M-H species within their structural composition, which can serve as extra hydrogen sources for chemical reactions in many cases. Additionally, they exhibit distinctive hydrogen absorption and desorption properties, making them a promising class of catalysts for hydrogenation and dehydrogenation reactions. In this Review, the mechanism and characterization of M-H species in catalytic reactions for M-H particles, molecular metal hydrides and hydride-doped metal nanoclusters were reviewed and compared. When metal oxides are used as catalysts, H2 can generally crack at the surface to produce highly M-H species to promote the reaction. Nevertheless, the intricate surface configuration of the catalyst and the transient nature of M-H intermediates have presented significant challenges in terms of detecting and characterizing them. A fundamental understanding of the reaction mechanisms and dynamic changes of M-H species could help design highly efficient catalysts for chemical reactions involving hydrogen.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The pivotal function of metal-hydride (M-H) species in numerous catalytic reactions has prompted extensive investigations. The roles and functions of their participation in the catalytic reactions depend on the electronegativity of the attached metal and coordination sphere. M-H species are commonly utilized in numerous catalytic reactions and are frequently regarded as critical intermediates[1-3]. For example, when metal oxides are employed as hydrogenation catalysts, the adsorbed H2 may undergo a homolytic or heterolytic dissociation on the surface of the oxide, subsequently combining with the metal to form highly active M-H species that exist on the surface or lattice of the oxide, which can promote the reaction or stabilize the catalyst[4,5]. However, the transient nature, low concentration, and high reactivity of these species, in addition to the complex surface structure of catalysts, have consistently posed significant challenges in achieving detailed characterization[6].

However, M-H species exhibit stable and homeostatic properties when acting as chemical components of metal hydrides. Metal hydrides can provide extra hydrogen sources and hydrogen transfer pathways for catalytic reactions. They exhibit distinctive hydrogen absorption-desorption characteristics and readily adjustable electronic structures, rendering them prospective efficient catalysts for hydrogen-involved reactions. Therefore, they are widely studied in important catalytic reactions such as olefin hydrogenation[7-9], CO2 hydrogenation[10-12] and NH3 synthesis[13,14]. Concurrently, compared with transient intermediates, the stability of M-H species facilitates further investigation into the aspects of spectral characterization and catalytic mechanism. Metal hydrides can be classified into four categories on the basis of the type of bonding between hydride and the metal:

(1) Interstitial hydrides: they are typically non-stoichiometric compounds, wherein hydride is incorporated into the lattice of a metal catalyst, such as LaNi5H5, PdHx and FeTiH1.7.

(2) Ionic hydrides: they are typically negative valences, and alkali and alkaline earth metals with low electronegativity are prone to form ionic hydrides, as exemplified by MgH2 and LiH.

(3) Complex hydrides: they contain compounds with well-defined formulas, usually consisting of metal cations and polyhydride anions.

(4) Covalent hydrides: metals with similar electronegativity to H, such as Ru, Rh, Pd, Ir, are readily formed to be covalent hydrides[15], wherein hydrides exhibit negative valence, as exemplified by CuH and BeH2.

However, the boundaries between the different types of hydrides are blurred. For instance, hydride-doped metal nanoclusters, which are emerging rapidly, are difficult to classify into any of the four hydride categories mentioned above, and a metal hydride can contain several hydrides at the same time, such as

In order to emphasize the role of M-H species in catalysis, this paper classifies metal hydrides into M-H particles, molecule metal hydrides, and hydride-doped metal nanoclusters that can exhibit characteristics of both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts based on the phase homogeneity of the catalytic reaction system. M-H species as original species have been compared with as intermediates in the reactions. Finally, the mechanism of M-H species in catalysis and research challenges are summarized.

METAL HYDRIDES

Metal hydride particles

Abundant M-H species exist in both the surface and bulk phase of M-H particles, which have good stability and can participate in catalytic reactions, so they have been extensively studied in catalysis and hydrogen storage. Among them, rare-earth-based AB5-type metal hydrides were known as good hydrogen storage materials, but they were one of the first metal hydrides to be considered for catalytic properties. As early as the latter half of the last century, Soga et al. studied the catalytic properties of intermetallic AB5 such as CaNi5, LaNi5, and alloy AB5 such as LaNi4M in olefin hydrogenation reaction and found that they exhibited high catalytic activity[17-19]. Whereafter, Johnson et al. studied the catalytic properties and mechanism of the intermetallic LaNi5Hx catalyst using 1-undecene hydrogenation as a model, and quantitatively confirmed the catalytic activity difference of a metal hydride precursor in different states[20]. The authors found that the improvements in the catalytic activity of metal hydrides can be attributed to three factors:

(1) There was highly concentrated H in the metal hydride bulk phase, which can provide H on the catalyst surface.

(2) The presence of the hydride phase caused the volume expansion of the catalyst particles, which helped the H to migrate from the bulk phase to the catalyst surface through microcracks and grain boundaries.

(3) When the M-H species in the bulk phase had high activity, the surface hydrogen had weak chemisorption, which can improve the hydrogenation reaction rate.

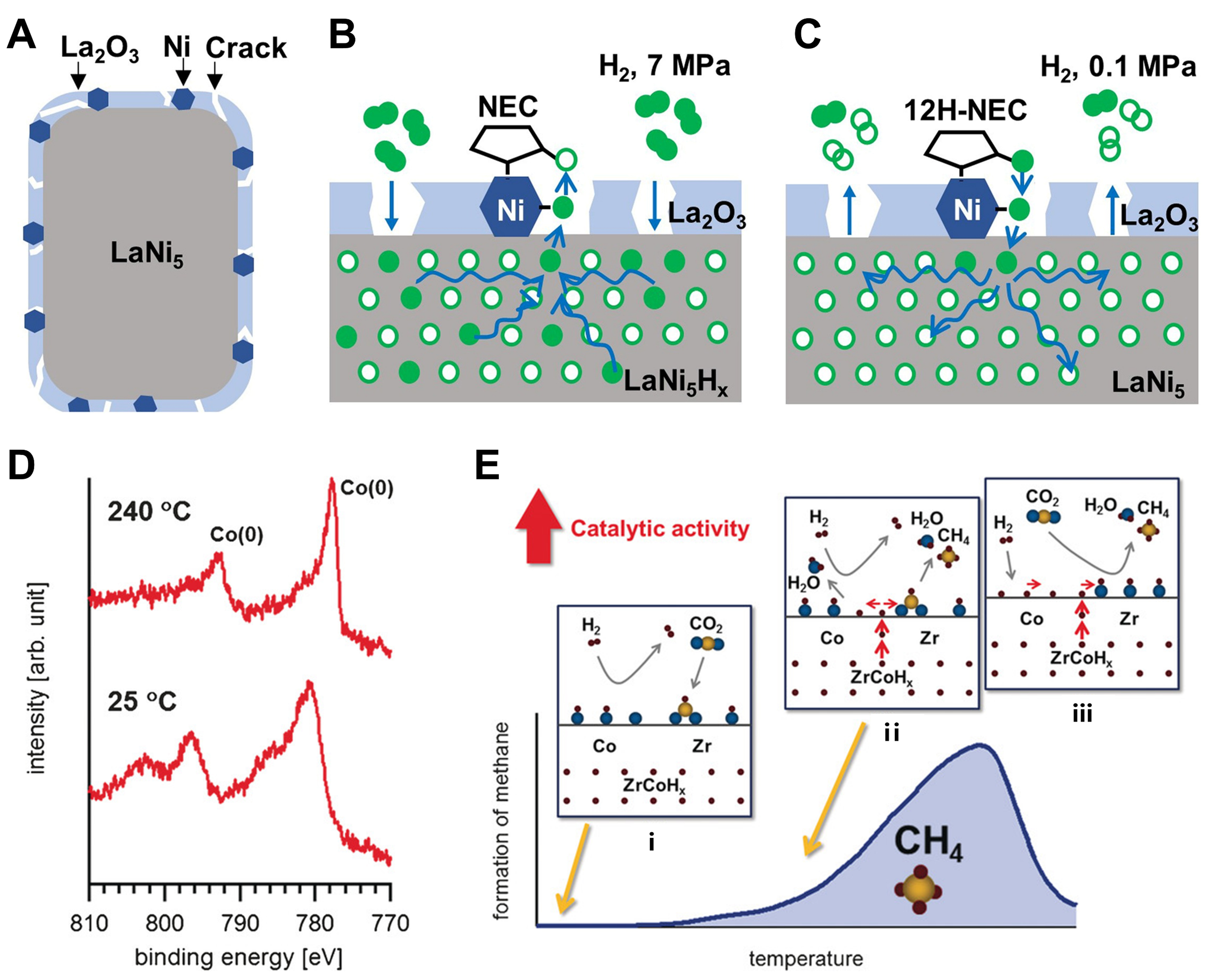

Recently, Yu et al. prepared homogeneous LaNi5.5 particles with a size of about 100 nm in molten salt by an improved CaH2 reduction method, showing a unique core-shell structure with LaNi5 core and Ni-rich shell

Figure 1. (A) Structure illustration of a LaNi5.5+x; (B) Hydrogenation process of NEC on LaNi5Hx at 7 MPa H2; (C) Dehydrogenation process of 12H-NEC on LaNi5 at 0.1 MPa H2. Reproduced from Ref[21]. Copyright (2021), with permission from Elsevier; (D) The Co 2p XP spectra of ZrCoH1.2 measured at 1.0 mbar H2, at 25 and 240 °C, respectively; (E) Reaction path for ZrCoHx catalyst in CO2 reduction. Reproduced from Ref[25]. Copyright (2016), with permission from John Wiley and Sons. NEC: N-ethylcarbazole.

Mg-based A2B-type and Zr-based metal hydrides have also been reported in catalytic studies. Kato et al. explored the source of catalytic activity of ZrCoHx and Mg2NiH4 in CO2 hydrogenation[25,26]. The catalytic performances of ZrCoHx (x = 0, 0.1, 1.2, 2.9) with different hydrogen contents were evaluated in a fixed-bed reactor, and it was found that the methane produced gradually increased with the hydrogen content. No methane production was observed when pristine intermetallic ZrCo was used as a catalyst. Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectroscopy (TOF-SIMS) and near ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (NAP-XPS) were used to analyze the surface changes of the catalyst during the reaction. It was found that ZrCoHx was initially covered by surface oxides, and the Co on the surface was reduced with the temperature increase under the inert air flow [Figure 1D]. In the hydrogen atmosphere, the degree of Co reduction was higher and the surface hydrogen concentration was also greater. A possible reaction mechanism was therefore proposed: CO2 adsorbed on zirconia to form formates, while the overflow of M-H species in the bulk phase led to reduction of cobalt oxide at the interface. Gaseous hydrogen molecules then struck the reduced Co atoms to dissociate into hydrogen atoms, and all the surface H spilled over to zirconia. Finally, the formates reacted with the H on the zirconia to form methane. Hydrogen desorption and absorption occurred throughout the process to achieve cyclic catalysis [Figure 1E]. However, the reaction path and mechanism lacked characterizations of in situ spectroscopy. Mg2NiH4 also had hydrogen desorption and hydrogen absorption steps in CO2 hydrogenation, but it showed a completely different phenomenon: in the process of hydrogen desorption under CO2 stream, Mg was selectively oxidized, which resulted in disproportionation of Mg2NiH4, thus forming a Mg-rich oxide layer on the surface, along with the formation of Ni particles and MgNi2. The higher concentration of basic MgO layers was prone to absorbing CO2; Ni particles served as active sites for H2 adsorption and dissociation. The dissociative adsorption of CO2 and subsequent hydrogenation led to further oxidation of the surface.

In addition to catalysis, the aforementioned rare-earth-based AB5-type and Mg-based A2B-type metal hydrides are widely used in hydrogen storage; Zr/Ti-based AB2-type and FeTi-based AB-type metal hydrides are also common hydrogen storage materials[27]. Metal hydrides utilize metals/alloys to absorb and release hydrogen gas at a certain temperature and pressure for hydrogen storage. The ability of metal hydrides to reversibly absorb and desorb H2 makes them very attractive for hydrogen storage applications. Some metals combine with hydrogen to form hydrides which are volatile compounds with low boiling points and cannot be used as hydrogen storage materials, such as CuH[28]; the chemical properties of the M-H species are one of the important influencing factors for hydrogen storage applications, hydrogen bonds that are too strong or too weak are not suitable for hydrogen storage. At present, the preparation technology and process of metal hydrides for hydrogen storage are relatively mature.

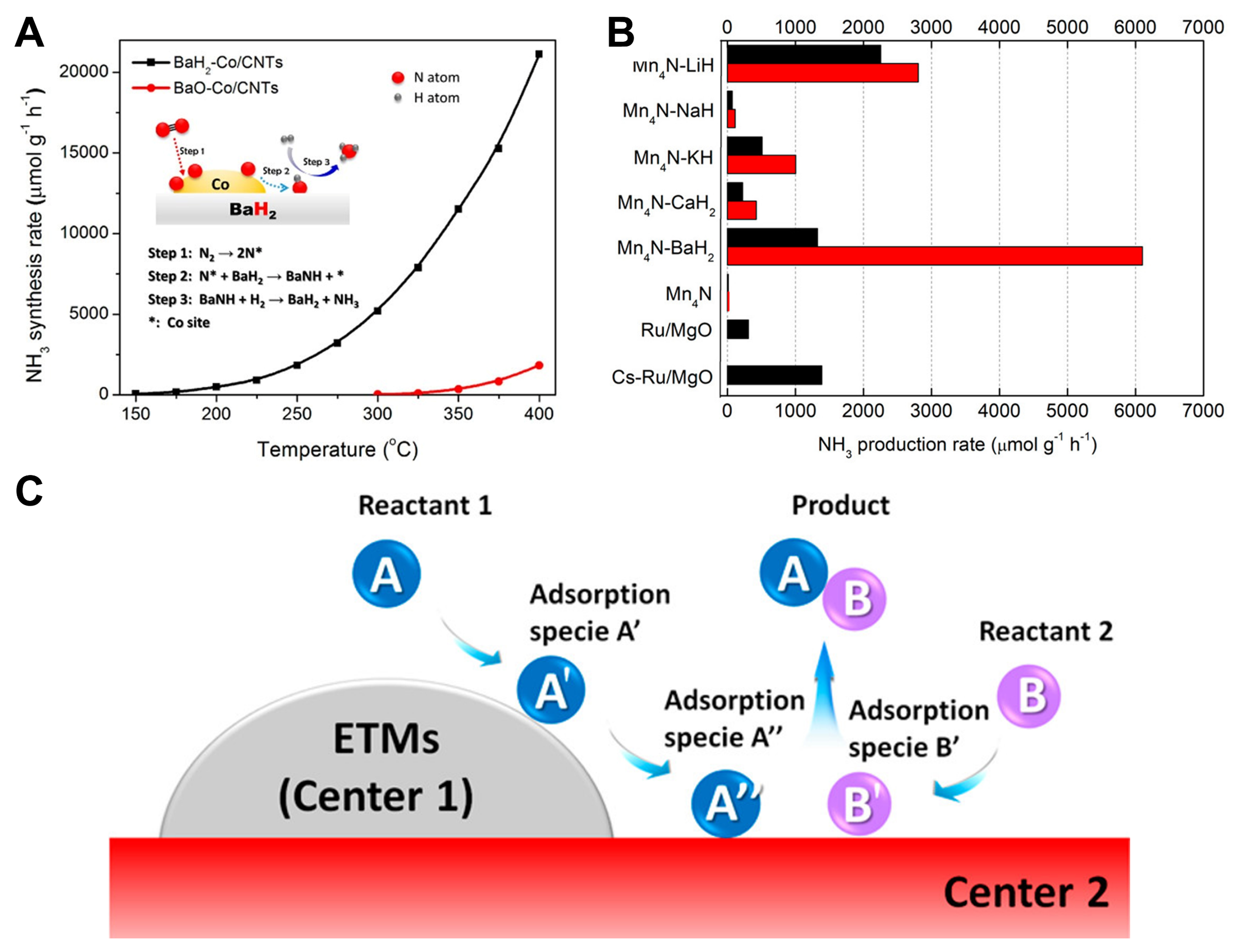

Alkali and alkaline-metal hydrides (AHs) such as LiH, NaH, KH, BaH2 and CaH2 that do not contain transition metals are also proven to be active for some catalytic reactions. Gao et al. reported a looped ammonia synthesis process, in which BaH2 acted as mediators and nitrogen carriers[29]. In this cycle, N2 was reduced by BaH2 to generate BaNH, which further decomposed to obtain BaH2 and NH3. The valence state of H in BaH2 varied between -1, 0, and +1. Although BaH2 demonstrated catalytic activity in the ammonia synthesis reaction, Ni-BaH2 yielded by the combination of BaH2 with Ni through ball milling exhibited significantly superior catalytic performance. The yield rate of NH3 was much higher than that of Cs-Ru/MgO under mild conditions below 250 °C[13]. Consequently, although transition metal-free hydrides have been demonstrated to be active and play crucial roles in some reactions, the activities are typically not remarkable before being combined with transition metals.

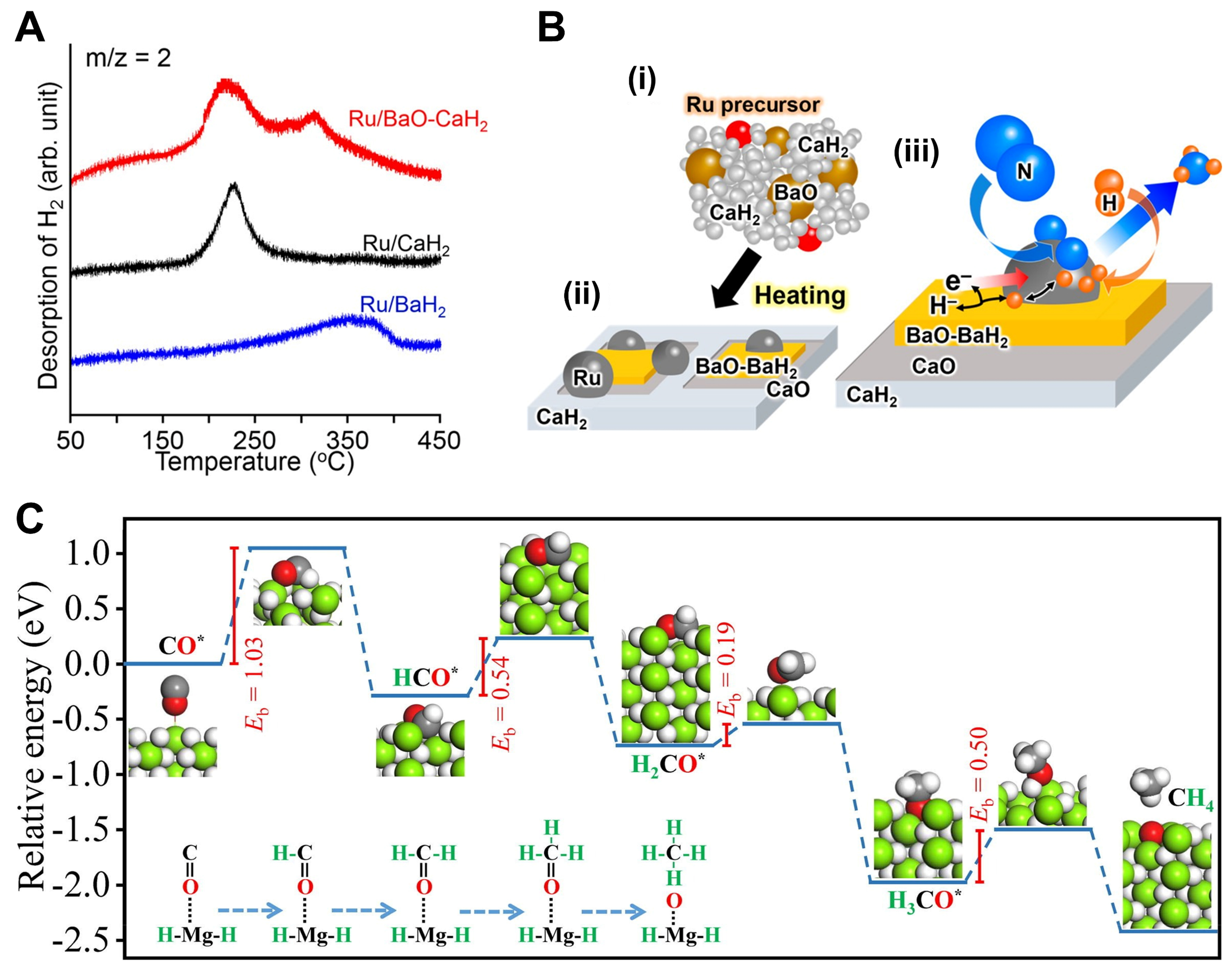

A series of catalysts, synthesized by combining LiH, NaH, BaH2 and other AHs with transition metals such as Co and Mn, demonstrated significant catalytic activities in ammonia synthesis [Figure 2][30,31]. Therefore, researchers used CaH2 and MgH2 as functional carriers to support transition metal particles to obtain a series of composite catalysts with high performances, such as Ru/BaO-CaH2[32], defect-rich MgH2/CuxO[33], Ni-MgO/MgH2[34] and Al-doped MgH2[12]. Ru/BaO-CaH2 was employed in ammonia synthesis, and the high electron-donating capacity of the resultant BaH2 was deemed pivotal to the high activity of the catalyst at low temperatures [Figure 3A]. The high electron-donating ability of BaH2 facilitated the adsorption and dissociation of N2, thus promoting the synthesis of ammonia. Concurrently, the absorption of H2 by metal hydrides diminished the adsorption of H2 on the surface of Ru, thereby impeding the phenomenon of hydrogen poisoning [Figure 3B]. Defect-rich MgH2/CuxO and carbon-confined MgH2 nanoparticles can achieve high C2-C4 selectivity and high CO2 conversion at low H2/CO2 ratios when applied to CO2 reduction. The abundant oxygen vacancies and Mg/O-heteroatom defects on MgH2/CuxO can facilitate the adsorption and activation of CO2, while the lattice H- in MgH2 with low concentration can promote the hydrogenation of CO2 and the formation of carbon chains to produce short-chain olefins. Ni-MgO/MgH2 and Al-doped MgH2 exhibited high selectivity for methane in the hydrogenation of CO2. Theoretical calculations[34] indicated that in the Ni-MgO/MgH2 system, CO2 preferentially adsorbed and activated on the surface of MgO, and hydrogenated by H+ on the surface of Ni-doped MgO to form CO* species (O-terminal hydrogenation). Subsequently, it reacted with H- on the surface of MgH2 to produce CH4 (C-terminal hydrogenation). The H- species provided by the surface of MgH2 ensured the continuous hydrogenation of CO2, which can be supplemented by H2 dissociation even when the surface H- species were consumed [Figure 3C].

Figure 2. (A) Temperature dependence of the NH3 synthesis rates of BaH2-Co/CNTs and BaO-Co/CNTs. The insert of (A) shows the three steps of NH3 synthesis catalyzed by BaH2-Co/CNTs. Reproduced from Ref[30]. Copyright (2017), with permission from American Chemical Society; (B) Comparison of NH3 yield of different catalysts, reaction condition: 10 bar syn-gas (N2:H2 = 1:3), 573 K,

Figure 3. (A) H2-TPD profiles of used Ru/CaH2, Ru/BaH2, and Ru/BaO-CaH2, which were performed under Ar flow (1 °C·min-1). The three catalysts were used in the NH3 synthesis reaction at 340 °C for 50 h; (B) Schematic diagram of the Ru/BaO-CaH2 catalyzed NH3 reaction. Reproduced from Ref[32]. Copyright (2018), with permission from American Chemical Society; (C) Reaction path with minimum energy for absorbed CO* hydrogenation to CH4. Reproduced from Ref[34]. Copyright (2021), with permission from Elsevier. TPD: Temperature-programmed desorption.

Based on the aforementioned examples, heterogeneous metal hydride catalysts typically played the following several roles in reactions: (1) providing additional H sources and H transfer routes; (2) facilitating hydrogen dissociation; (3) establishing new reaction mechanisms; (4) regulating the electronic structure of the catalyst. The intrinsic properties of M-H in metal hydrides and reaction conditions can both influence their promoting effects in catalysis. In the case of interstitial hydrides, such as LaNi5H5, high H-mobility was typically the determining factor in terms of high activity. In contrast, MgH2, CaH2 and other ionic hydrides generally exhibited low H-mobility, rendering them ineffective for hydrogenation reactions such as olefin hydrogenation which proceeded under milder conditions. In the context of ammonia synthesis, the typical reaction temperature exceeded 250 °C. At this temperature, the tuning effect of metal hydrides on the electronic structure became dominant, thereby rendering metal hydrides with low H-mobility effective catalysts.

However, it is obvious that the majority of relevant works on mechanism research relied on theoretical calculation and lacked in-situ characterization data and direct experimental evidence. Because of the heterogeneous structure of particle catalyst, the activity data and mechanism obtained can only reflect the average of catalyst. Concurrently, heterogeneous metal hydride catalysts were mostly synthesized via traditional metallurgical methods, which usually required a long time activation treatment with H2 under high pressure before catalytic reaction, and usually had a particle size in the micron range and a relatively low surface area.

Molecular metal hydrides

Molecular metal hydrides, which are important homogeneous catalysts, have a long study history started from the discovery of the first example H2Fe(CO)4[35] in the 1930s. These materials are concentrated in d-zone transition metals and f-zone elements, with a small number of alkaline earth metal complexes also reported. Transition-metal polyhydrides complexes LnMHx have been used as homogeneous catalysts in over 40 organic reactions, such as hydrogenation of olefins and alkynes, formation of amines, hydrosilylation, and so on, which were summarized in detail by Babón et al. in terms of catalytic reactions[36]. Compared with heterogeneous catalysts, molecular metal hydride catalysts not only have higher activity, selectivity and mild reaction conditions, but also have great advantages in studying catalytic mechanisms and the dynamic changes of M-H during reactions. Molecular metal hydrides have given rise to a series of conceptual studies on M-H, such as the mechanisms of the collective motions of the H surrounding the metal center[37], their thermodynamic acidity[38-40] or hydricity[41], the insight of interconversion processes between different H ligands, and the impact of the presence of M–H bonds of different types on the catalytic properties of the complexes. These are difficult to study by experiments and calculations in heterogeneous catalyst systems.

The versatility of molecular metal hydrides can be attributed to the manner, in which H coordinates with metal centers and the diversity of chemical properties of M-H. In general, H ligands can coordinate with metals in the form of H+/H0/H- or in the form of H2. Molecular metal hydrides may have multiple H ligands with different coordination modes simultaneously.

A classical molecular metal hydride RuHCl(PPh3)3 which contains a hydride ligand was used by Sasson and Rempel to catalyze the rearrangement of unsaturated alcohols into saturated ketones[42]. RuHCl(PPh3)3 containing M-H showed a threefold greater activity than RuCl2(PPh3)3, demonstrating the critical role of

Figure 4. (A) Inner-sphere mechanism for aldehyde/ketone transfer hydrogenation catalyzed by [Ru–H] supported with coumarin-amide-based ligands. Reproduced from Ref[43]. Copyright (2023), with permission from American Chemical Society; (B) Stoichiometric C=C coupling reaction between [{(Dippnacnac)Mg(μ-H)}2] and CO, and CO reduction with PhSiH3 catalyzed by

Figure 5. (A) Reaction path for dehydrogenation of formic acid catalyzed by (iPrPPRP)CoH(PMe3), and the variation of

Many molecular transition metal polyhydrides have also shown high activities in numerous catalytic reactions. Osmium trihydrides OsH3(acac)(PiPr3)2 (Hacac = acetylacetone) and OsH3{k2-Npy,Nimine(BMePI)}(PiPr3)3 [HBMePI = 1, 3-bis (6’-methylpyridine-2’-imine) isoindoline] reported by Esteruelas et al. achieved high yield of H2 in cyclic amine dehydrogenation[47,48]. Zeiher et al. employed Rhenium-heptahydride ReH7(PCy3)2 in the dehydrogenation of 1-arylethanols[49], and cobalt-trihydride CoH3{κ3-P,N,P-[py(CMe2PiPr2)2]} reported by Lapointe et al. can obtain 4-octyne with a yield of 99% in hydrogenation of trans-4-octene[50]. The dihydride-ruthenium(II)-bis(dihydrogen) complex RuH2-(η2-H2)2(PCy3)2 with two H ligands and two dihydrogen ligands, originally applied in dehydrogenative cyclization, corresponding cyclic products were obtained in moderated-good yields after 3-72 h at 25 °C[51], and Borowski et al. found the catalyst to be interesting for hydrogenation of aromatic hydrocarbons as well[52,53]. [Ir(η4-COD)(Me2Bzim)(PPh3)]+ (Me2Bzim = N,N-dimethyl-benzimidazolylidene) reported by Dobereiner

The molecular metal hydrides were transition metal-based, with only a few alkaline earth metal hydrides having been reported thus far and primarily those magnesium-based. That was due to the large ionic radius of the heavier alkaline metals, namely Ca, Sr, Ba and Ra, which resulted in high activities of hydrides and facilitated the Schlenk rearrangement to form insoluble inorganic salts [AeH2]∞ (Ae = alkaline earth metals). Anker et al. made many efforts in the synthesis and catalysis of Mg-based molecular metal hydrides. Among them, they synthesized [{(Dippnacnac)Mg}2(μ-H)}2] and used it for catalytic reduction of CO in the presence of PhSiH3 to produce PhSiH2-CH3 and (PhH2Si)2O [Figure 4B]. The reaction mechanism was shown in Figure 4C and the driving force of the catalytic reaction was derived from the formation of siloxane

Molecular metal hydride catalysts have great advantages in the study of catalytic mechanism, but they are susceptible to inactivation and difficult to recycle, which limit their practical applications.

Hydride-doped metal nanoclusters

Metal nanoclusters have recently emerged as a subject of considerable interest within the field of catalysis. They exhibit the characteristics of both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts, acting as a bridge between nanoparticles and small molecule complexes. The precise atomic composition and crystal structure, clear surface bonding mode and monodispersion of nanoclusters afford them significant advantages in the study of structure-activity relationships and the establishment of catalytic models, as well as in the investigation of catalytic mechanisms[57-59]. Despite the numerous reports on hydride-doped metal nanoclusters, the difficulty of synthesis and poor stability limit their applications in catalysis research[60,61].

Sun et al. reported a novel atomically accurate mercaptan protected Cu-hydride nanocluster

Figure 6. (A) Energy change and structures of intermediates in of a supposed route involves two H from Cu25H10; (B) 2H NMR spectra of Cu25D10 after catalysis with H2 and fresh Cu25D10. Reproduced from Ref[62]. Copyright (2019), with permission from American Chemical Society; (C) Conversion for 4-NP reduction over Ag25Cu4-1 (1 for short), Ag25Cu4H8-2H (2H for short), and Ag25Cu4-1 in the presence of H2O2; (D) Schematic diagram of the conversion from 1 and 2H and their performance on the catalytic reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP. With successively addition of H2O2 and NaBH4, 1 can gradually convert to 2H with better catalytic performance. Reproduced from Ref[65]. Copyright (2022), with permission from American Chemical Society. NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance; 4-NP: 4-nitrophenol; 4-AP: 4-aminophenol.

The reaction conditions for the reduction of 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) by NaBH4 to 4-aminophenol (4-AP) are mild; therefore, it is a commonly used “model catalytic reaction” to study the properties of hydride-doped metal nanoclusters. Ni et al. reported three structurally similar PdAg nanoclusters [PdHAg19(dtp)12] [dtp = S2P(OiPr)2] (PdHAg19), [PdHAg20(dtp)12]+ (PdHAg20) and [PdAg21(dtp)12]+[64]. It was observed that PdHAg19 and PdHAg20 contained interstitial hydrogen while PdAg21 did not. In the reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP, to achieve the complete transformation, PdHAg19 needed 25 min, PdHAg20 needed 30 min, and PdAg21 needed 60 min. Although there was no other experimental evidence, the authors attributed this performance difference to interstitial hydrogen: its presence led to a significant distortion of the nanocluster core, and this structural change may affect the catalytic performance; and interstitial hydrogen may be directly involved in the catalytic process. Yuan et al. reported two bimetal clusters: Ag25Cu4Cl6(dppb)6(PhC≡C)12

Liu et al. reported two structurally similar copper hydride nanoclusters protected by amido-ligands (Tf-dpf):Cu11H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2 (Cu11) and [Cu12H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2]·OAc (Cu12)[66]. According to the DFT calculations, the two nanoclusters had distinct hydride locations, with Cu11 having three interfacial μ5-H and Cu12 having three interfacial μ6-H. In the reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP, the activity of Cu11 was much higher than that of Cu12:Cu11 can completely convert 4-NP to 4-AP within 10 min, while the yield of equivalent Cu12 was only 5% when reacting for 30 min. Because the structures of the two clusters were similar, the authors focused on the different Cu-H species of the two clusters. According to deuteration experiments, μ5-H in

The catalytic properties of hydride-doped metal nanoclusters in hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and electrocatalytic CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) have also been reported. Kulkarni et al. reported a gold nanocluster [Au24(NHC)14Cl2H3]3+ (Au24H3) stabilized by N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC), which was the first time that gold nanoclusters containing hydrides were prepared[67]. Based on DFT calculations, three metal hydrides acted as bridging ligands to connect the two Au12 cores, and their wavenumbers in the IR spectrum ranged from 1,114 to 1,316 cm-1. Au24H3 exhibited a CO Faraday efficiency of over 90% in CO2RR, and calculations suggested that this may be due to the metal hydride assisting in the activation of the CO2 into an easily reducible configuration. [Au22H3(dppe)3(PPh3)8]3+ (Au22H3) reported by Gao et al. also had three bridge-H connect two Au11 cores[68]. The electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO showed high selectivity and reactivity [92.7% CO Faradaic efficiency (FECO), 134 A/gAu mass activity], and the catalytic performance was significantly better than that of Au11. Figure 7A and B showed the catalytic pathway: bridge-H on Au22H3 could directly hydrogenate CO2 to form adsorbed *COOH, with a much lower Gibbs free energy (ΔG) than Au11. Then absorbed *COOH formed by electrochemical proton reduction absorbed CO* and water. Finally, the CO desorbed, and the consumed bridge-H were replaced by proton reduction. However, Au-H in clusters did not all promote CO generation. The [Au7(PPh3)7H5](SbF6)2 (Au7H5) clusters reported by Tang

Figure 7. (A) Structures obtained from DFT of intermediates for Au22H3 in electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to CO; (B) Free energy change for Au11 and Au22H3 in CO2RR. Reproduced from Ref[68]. Copyright (2022), with permission from American Chemical Society; Free energy change for Au7H5 (C) and Au8 (D) in CO2RR and HER. Reproduced from Ref[69]. Copyright (2023), with permission from John Wiley and Sons. DFT: Density functional theory; HER: hydrogen evolution reaction.

Brocha Silalahi et al. reported two clusters: [PdHCu11{S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)4] (PdHCu11) and [PdHCu12

Although hydride-doped nanoclusters have unique advantages in the study of catalytic mechanisms, the current relevant work has not been deeply studied in terms of its dynamic changes and the roles of M-H species in catalysis, with little experimental evidences and mainly relying on theoretical calculations.

M-H SPECIES PRODUCED IN CATALYSIS

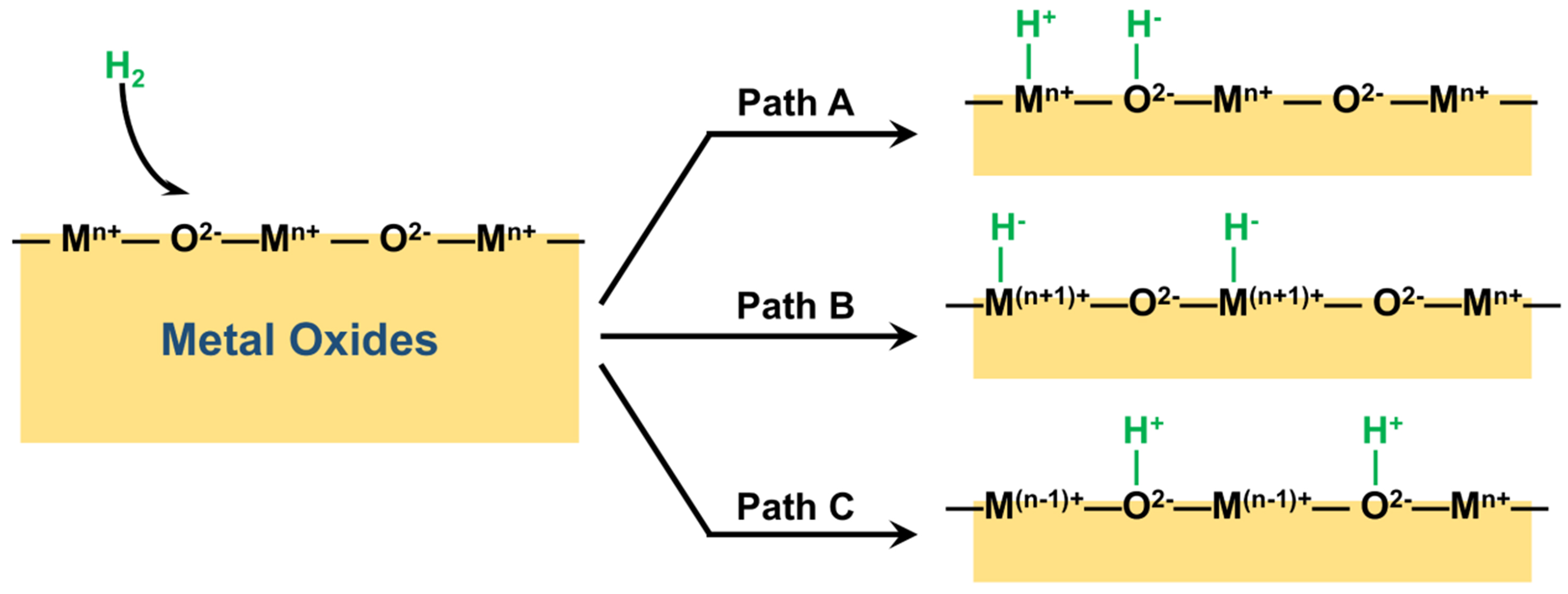

In reactions involving hydrogen, M-H species formed by H2 cleaving on the surface of metal oxides are typically important reactive species or reaction intermediates and have been extensively studied. As illustrated in Figure 8, H2 is usually decomposed in three ways after adsorbed on the surface of metal oxides. Among these, paths A and B can form M-H. However, the surface structures of oxides are complex, comprising numerous hydroxyl groups and hydrated proton [(H2O)n-H+] species. The M-H species as intermediates are typically highly active and possess transient properties, leading to the difficulty of their characterization.

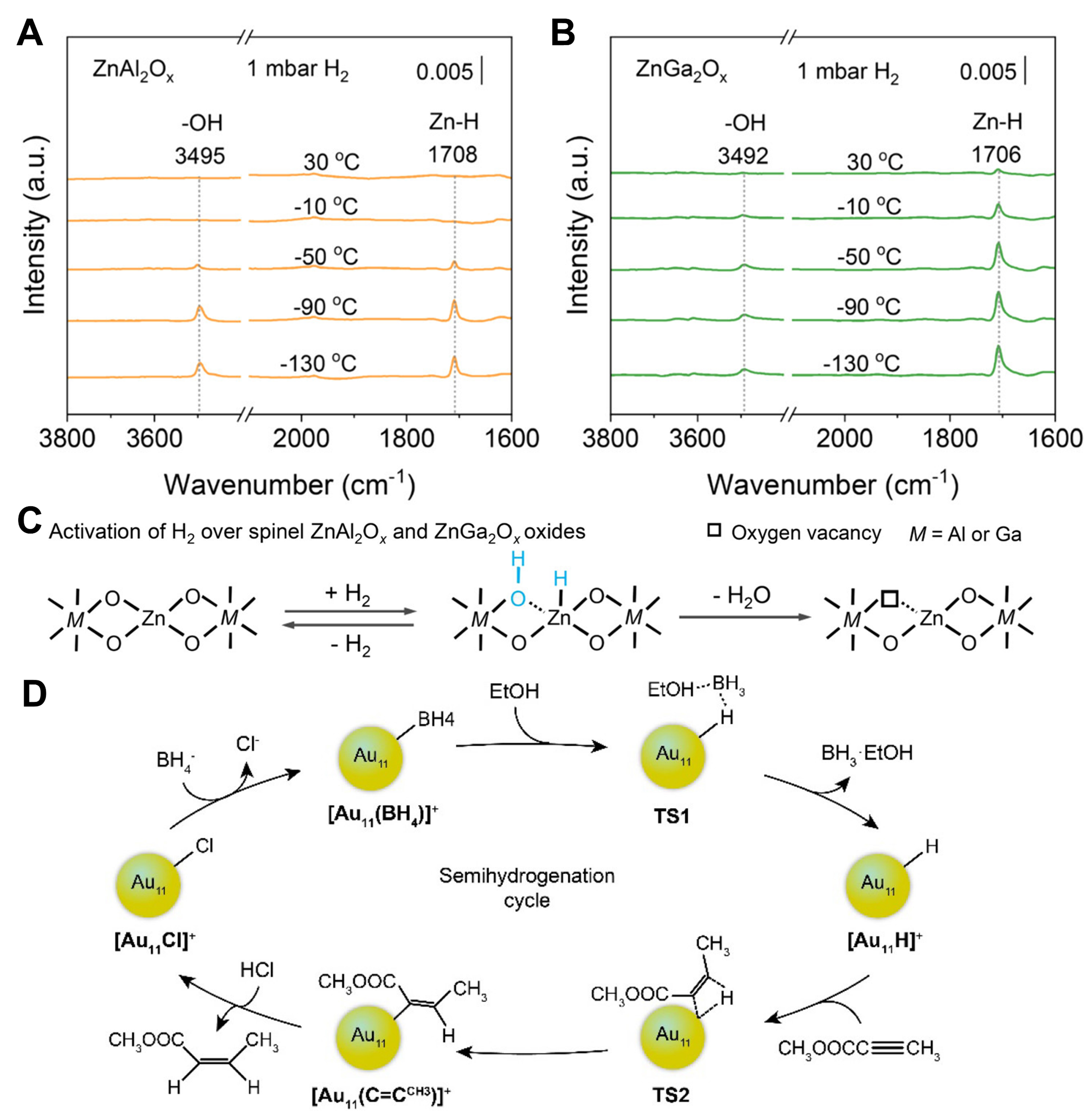

Nonreducible oxides such as Cr2O3, CeO2 and Ga2O3 typically produce M-H through heterolytic cleavage [path A in Figure 8]. Chen et al. detected active Ga-H species on the surface of Ga2O3 using solid-state NMR spectroscopy, which was the first NMR evidence of Ga-H formation on the surface of Ga2O3[71]. After pre-activation of Ga2O3 in an inert gas, the dissociation of H2 on the surface of Ga2O3 was studied by switching to hydrogen at different temperatures, and the reaction was immediately stopped by using a liquid nitrogen quenching device to capture the active intermediates. The DFT calculations indicated that Ga-H was formed by heterolysis of H2, accompanied by the generation of bridging Ga-OH which existed as a tetra-ordinated [HGaO3] structure. In the CO2 hydrogenation, after Ga2O3 activated H2 to form Ga-H, CO2 was directly inserted into Ga-H to form HCOO*, which was the key to the reaction. Wang et al. studied the catalytic performance of a series of spinel oxides (AB2O4) in carbon dioxide hydrogenation, among which ZnAl2Ox and ZnGa2Ox showed good activity in methanol synthesis[72]. Ultra-high vacuum (UHV)-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) coupled H2-temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) was used to study M-H species on the surface of ZnAl2Ox and ZnGa2Ox. At 130 °C, with the increase of H2 pressure, two peaks appeared and gradually strengthened at 3,495 and 1,708 cm-1, which belonged to the -OH group and Zn-H species, respectively. As the temperature rose to 30 °C, the two peaks gradually weakened

Figure 9. UHV-FTIR spectra of (A) ZnAl2Ox and (B) ZnGa2Ox obtained by firstly adsorbing hydrogen in 1 mbar of H2 at low temperatures, followed by UHV evacuation and the annealing from -130 to 30 °C; (C) Hydrogen activation diagram on ZnAl2Ox and ZnGa2Ox. Reproduced from Ref[72]. Copyright (2024), with permission from American Chemical Society; (D) Reaction cycle for [Au11Cl2(dppee)4]+ catalyst in Semi-hydrogenation of alkynes. Reproduced from Ref[80]. Copyright (2022), with permission from American Chemical Society. UHV-FTIR: Ultra-high vacuum-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy.

If oxides are supported by metal atoms such as Pd, Pt, Ru and Rh that have high activation capacity for H2, the obtained catalysts are prone to exhibit the interesting phenomenon of “hydrogen spillover”, which is promoted by the abundant hydroxyl species on the oxide surface. This phenomenon was first observed in 1964 by Khoobiar on Pt/WO3 catalyst[75], which was later verified by Sierfelt and Teicher. The process of hydrogen spillover referred to the migration of surface adsorbed hydrogen from a hydrogen-rich phase (such as a metal surface), to a hydrogen-deficient phase (such as a carrier). The hydrogen spillover effects can enhance the number of active sites on the catalysts, thereby allowing for an increase in catalytic activity through the addition of further carriers[76,77]. For example, Kang et al. reported that Ru/(TiOx)MnO catalysts showed good catalytic activity in the reaction of CO2 reduction to CO[78]. The hydrogen spillover phenomenon of H2 dissociation on Ru nanoparticles and migration through the TiOx/MnO interface was observed, which was the key to the enhancement of the activity of the catalyst. Hydrogen spillover can also occur on non-oxide supports. Kyriakou et al. utilized hydrogen spillover effect to develop a highly efficient catalyst, which served as an illustrative example[79]. In vacuum environment, Pd was heated to vaporize, and then attached to the Cu surface in a single atom state to form a single atom alloy phase. The single-atom Pd on the Cu surface was used as the catalytic active site for hydrogenation. H2 molecules were adsorbed at the Pd single atom site, releasing H atoms which overflowed to the exposed Cu surface region. The ability of Cu to bind H was very weak, allowing H to move freely on the surface of copper and establish complete contact with organic molecules, thereby facilitating chemical reactions. This greatly reduced the energy barrier for H2 adsorption and subsequent desorption, thus greatly improving the selectivity of the hydrogenation of styrene or acetylene.

Additionally, the formation of M-H intermediates from hydrogenation reactions has been observed in the case of metal nanoclusters. The [Au11Cl2(dppee)4]+ cluster reported by Dong et al. was the first direct observation of metal hydride as an important intermediate in the hydrogenation reaction of gold-based nanocatalysts[80]. Two unstable Cl- ligands existed on the cluster, which can be exchanged with BH4- to form [Au11HCl(dppee)4]+ with H- ligands. The highly activated H- reacts with alkynes to generate gold-alkenyl intermediates. Under acidic conditions, the alkene products were further released [Figure 9D]. When using three different alkynes as substrates, the target alkene products were obtained with yields all higher than 90% (HC≡CPh: 90%, HC≡CCOOCH3: 99%, HC≡CCOOC2H5: 97%).

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

The roles of M-H species in catalytic reactions are mainly reflected in the following aspects:

(1) Active center of hydrogenation. In many hydrogenation reactions including the hydrogenation of olefins, CO and CO2, NH3 synthesis and the reduction of unsaturated compounds, the M-H species serve as the active center on the catalyst surface. They are capable of absorbing and activating H2, thereby providing hydrogen atoms or hydrogen ions for the reactions.

(2) Promoting hydrogen dissociation. M-H species have the capacity to facilitate the dissociation of H2 on the catalyst surface to generate active hydrogen species, which can further interact with the reactant molecules to promote the reaction.

(3) Regulating reaction selectivity. The presence of M-H species can affect the active sites on the catalyst surface, modulate the adsorption capacity of reactants and products by changing the properties of these sites, thus affecting the selectivity of the reaction.

(4) Participating in the electron transfer process. In some REDOX reactions, M-H species participate in the electron transfer process, and they can act as electron donors or acceptors, affecting the electronic properties of the catalyst, which can in turn affect the activity and stability of the catalytic reaction.

(5) Preventing deactivation of catalysts. In some cases, M-H species can protect the catalyst surface from toxic substances. For example, when reacting with sulfur compounds, the presence of M-H species weakens the adsorption of sulfur compounds to the catalysts, thus extending the life.

(6) Promoting hydrogen spillover. In some catalyst systems, M-H species can migrate from one part of the catalyst to another through the so-called “hydrogen spillover” phenomenon, thereby evenly distributing active hydrogen on the catalyst surface and improving the overall catalytic efficiency.

In conclusion, the roles of M-H species in catalytic reactions are multifaceted. They not only directly participate in the reaction, but also affect the activity, selectivity and stability by regulating the chemical and physical properties of the catalyst surface. A fundamental understanding of the roles of M-H species in catalytic processes is important for the design and optimization of high-performance catalysts.

However, it is difficult to characterize and understand the dynamics and roles of M-H species during the catalytic reactions. M-H species are ubiquitous in catalytic reactions as transient intermediates and they have been experimentally studied using techniques such as in situ characterization or instant quenching capture under harsh conditions in some reported studies. When the M-H species are parts of the chemical composition of metal hydrides, the isolability can reduce the difficulty of characterization. The M-H species in molecular hydrides have been extensively studied in many catalytic reactions. However, since molecular hydrides typically act as homogeneous catalysts, they are prone to deactivation and difficult to recover, which limit their practical applications. In contrast, metal hydride particles, which serve as heterogeneous catalysts, have been verified to involve the original M-H species in catalytic reactions through isotopic labeling and other experiments. However, almost all of the current studies only give rise to an ensemble average of the catalytic performance due to the structural polydispersity and heterogeneity of heterogeneous particle catalysts. Hydride-doped metal nanoclusters with precise structure and size monodispersity have combined the features of homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts, offering significant advantages for studying catalytic reaction mechanisms and dynamic changes of M-H species. However, the research on these nanoclusters in catalytic reactions is still limited. Future research might focus on the new methods for obtaining atomically precise M-H catalysts and developing more advanced techniques such as atomic spatial resolution and millisecond temporal resolution, which are very challenging yet highly rewarding.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgements

The Graphic Abstract of this article adapts the illustrations of hydride-doped metal nanocluster with permission from[68]. Copyright @ 2022 American Chemical Society.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the project: Zhu, Y.

Wrote the manuscript: Tang, S.; Cai, X.; Ding, W.; Zhu, Y.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

We acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22125202, 92461312, U24A20487, 92361201) and Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20220033).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

2. Yu, H.; Li, X.; Zheng, J. Beyond hydrogen storage: metal hydrides for catalysis. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 3139-57.

3. He, T.; Cao, H.; Chen, P. Complex hydrides for energy storage, conversion, and utilization. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1902757.

4. Li, Z.; Huang, W. Hydride species on oxide catalysts. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2021, 33, 433001.

5. Xiong, M.; Gao, Z.; Qin, Y. Spillover in heterogeneous catalysis: new insights and opportunities. ACS. Catal. 2021, 11, 3159-72.

6. Copéret, C.; Estes, D. P.; Larmier, K.; Searles, K. Isolated surface hydrides: formation, structure, and reactivity. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 8463-505.

7. Tokmic, K.; Markus, C. R.; Zhu, L.; Fout, A. R. Well-defined cobalt(I) dihydrogen catalyst: experimental evidence for a Co(I)/Co(III) redox process in olefin hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11907-13.

8. Tokmic, K.; Fout, A. R. Alkyne semihydrogenation with a well-defined nonclassical Co-H2 catalyst: a H2 spin on isomerization and E-selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13700-5.

9. Teschner, D.; Borsodi, J.; Wootsch, A.; et al. The roles of subsurface carbon and hydrogen in palladium-catalyzed alkyne hydrogenation. Science 2008, 320, 86-9.

10. Ziebart, C.; Federsel, C.; Anbarasan, P.; et al. Well-defined iron catalyst for improved hydrogenation of carbon dioxide and bicarbonate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 20701-4.

11. Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Meiwes-Broer, K. H.; Ganteför, G.; Bowen, K. CO2 activation and hydrogenation by PtHn- cluster anions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 9644-7.

12. Chen, H.; Ma, N.; Cheng, C.; et al. Hydrogen activation on aluminium-doped magnesium hydride surface for methanation of carbon dioxide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 515, 146038.

13. Wang, P.; Chang, F.; Gao, W.; et al. Breaking scaling relations to achieve low-temperature ammonia synthesis through LiH-mediated nitrogen transfer and hydrogenation. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 64-70.

14. Kobayashi, Y.; Tang, Y.; Kageyama, T.; et al. Titanium-based hydrides as heterogeneous catalysts for ammonia synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18240-6.

15. Wang, Q.; Pan, J.; Guo, J.; et al. Ternary ruthenium complex hydrides for ammonia synthesis via the associative mechanism. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 959-67.

16. Spektor, K.; Crichton, W. A.; Filippov, S.; Simak, S. I.; Häussermann, U. Exploring the Mg-Cr-H system at high pressure and temperature via in situ synchrotron diffraction. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 11043-50.

17. Soga, K.; Imamura, H.; Ikeda, S. Hydrogenation of ethylene over lanthanum-nickel (LaNi5) alloy. J. Phys. Chem. 1977, 81, 1762-6.

18. Soga, K. Hydrogenation of ethylene over some intermetallic compounds. J. Catal. 1979, 56, 119-26.

19. Barrault, J.; Guilleminot, A.; Percheron-Guegan, A.; Paul-Boncour, V.; Achard, J. Olefin hydrogenation over some LaNi5-xMx intermetallic systems. Appl. Catal. 1986, 22, 263-71.

20. Johnson, J. Behavior of hydrided and dehydrided LaNi5Hx as an hydrogenation catalyst. J. Catal. 1992, 137, 102-13.

21. Yu, H.; Yang, X.; Jiang, X.; et al. LaNi5.5 particles for reversible hydrogen storage in N-ethylcarbazole. Nano. Energy. 2021, 80, 105476.

22. Zhong, D.; Ouyang, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Jia, Y.; Zhu, M. Metallic Ni nanocatalyst in situ formed from LaNi5H5 toward efficient CO2 methanation. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2019, 44, 29068-74.

23. Yang, S.; Han, S.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Hu, L. Effect of substituting B for Ni on electrochemical kinetic properties of AB5-type hydrogen storage alloys for high-power nickel/metal hydride batteries. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 2011, 176, 231-6.

24. Choi, H. S.; Park, C. R. Theoretical guidelines to designing high performance energy storage device based on hybridization of lithium-ion battery and supercapacitor. J. Power. Sources. 2014, 259, 1-14.

25. Kato, S.; Matam, S. K.; Kerger, P.; et al. The origin of the catalytic activity of a metal hydride in CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 6028-32.

26. Kato, S.; Borgschulte, A.; Ferri, D.; et al. CO2 hydrogenation on a metal hydride surface. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 5518-26.

27. Hou, Z.; Guo, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. Hydrogen storage and stability of rare earth-doped TiFe alloys under extensive cycling. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2025, 136, 469-76.

28. Iribarren, I.; Sánchez-Sanz, G.; Elguero, J.; Alkorta, I.; Trujillo, C. Reactivity of coinage metal hydrides for the production of H2 molecules. ChemistryOpen 2021, 10, 724-30.

29. Gao, W.; Guo, J.; Wang, P.; et al. Production of ammonia via a chemical looping process based on metal imides as nitrogen carriers. Nat. Energy. 2018, 3, 1067-75.

30. Gao, W.; Wang, P.; Guo, J.; et al. Barium hydride-mediated nitrogen transfer and hydrogenation for ammonia synthesis: a case study of cobalt. ACS. Catal. 2017, 7, 3654-61.

31. Chang, F.; Guan, Y.; Chang, X.; et al. Alkali and alkaline earth hydrides-driven N2 activation and transformation over Mn nitride catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 14799-806.

32. Hattori, M.; Mori, T.; Arai, T.; et al. Enhanced catalytic ammonia synthesis with transformed BaO. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 10977-84.

33. Chen, H.; Liu, P.; Li, J.; et al. MgH2/CuxO hydrogen storage composite with defect-rich surfaces for carbon dioxide hydrogenation. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 31009-17.

34. Chen, H.; Liu, P.; Liu, J.; Feng, X.; Zhou, S. Mechanochemical in-situ incorporation of Ni on MgO/MgH2 surface for the selective O-/C-terminal catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 to CH4. J. Catal. 2021, 394, 397-405.

35. Heiber, W.; Leutert, F. Äthylendiamin-substituierte Eisencarboyle und eine neue Bildungsweise von Eisencarbonylwasserstoff (XI. Mitteil. über Metallcarbonyle). Ber. dtsch. Chem. Ges. A/B. 1931, 64, 2832-9.

36. Babón, J. C.; Esteruelas, M. A.; López, A. M. Homogeneous catalysis with polyhydride complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 9717-58.

37. Ortuño, M. A.; Vidossich, P.; Conejero, S.; Lledós, A. Orbital-like motion of hydride ligands around low-coordinate metal centers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 14158-61.

38. Morris, R. H. Estimating the acidity of transition metal hydride and dihydrogen complexes by adding ligand acidity constants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 1948-59.

39. Morris, R. H. Brønsted-Lowry acid strength of metal hydride and dihydrogen complexes. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 8588-654.

40. Zhu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Burgess, K. Carbene-metal hydrides can be much less acidic than phosphine-metal hydrides: significance in hydrogenations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6249-53.

41. Wiedner, E. S.; Chambers, M. B.; Pitman, C. L.; Bullock, R. M.; Miller, A. J.; Appel, A. M. Thermodynamic hydricity of transition metal hydrides. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 8655-92.

42. Sasson, Y.; Rempel, G. L. Homogeneous rearrangement of unsaturated carbinols to saturated ketones catalyzed by ruthenium complexes. Tetrahedron. Lett. 1974, 15, 4133-6.

43. Yadav, S.; Gupta, R. Base-free transfer hydrogenation catalyzed by ruthenium hydride complexes of coumarin-amide ligands. ACS. Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 8533-43.

44. Pandey, B.; Krause, J. A.; Guan, H. Cobalt-catalyzed additive-free dehydrogenation of neat formic acid. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 13781-91.

45. Liu, T.; Guo, M.; Orthaber, A.; et al. Accelerating proton-coupled electron transfer of metal hydrides in catalyst model reactions. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 881-7.

46. Roberts, J. A.; Appel, A. M.; DuBois, D. L.; Bullock, R. M. Comprehensive thermochemistry of W-H bonding in the metal hydrides CpW(CO)2(IMes)H, [CpW(CO)2(IMes)H]•+, and [CpW(CO)2(IMes)(H)2]+. Influence of an N-heterocyclic carbene ligand on metal hydride bond energies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14604-13.

47. Esteruelas, M. A.; Lezáun, V.; Martínez, A.; Oliván, M.; Oñate, E. Osmium hydride acetylacetonate complexes and their application in acceptorless dehydrogenative coupling of alcohols and amines and for the dehydrogenation of cyclic amines. Organometallics 2017, 36, 2996-3004.

48. Buil, M. L.; Esteruelas, M. A.; Gay, M. P.; et al. Osmium catalysts for acceptorless and base-free dehydrogenation of alcohols and amines: unusual coordination modes of a BPI anion. Organometallics 2018, 37, 603-17.

49. Zeiher, E. H. K.; Dewit, D. G.; Caulton, K. G. Mechanistic features of carbon-hydrogen bond activation by the rhenium complex ReH7[P(C6H11)3]2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 7006-11.

50. Lapointe, S.; Pandey, D. K.; Gallagher, J. M.; et al. Cobalt complexes of bulky PNP ligand: H2 activation and catalytic two-electron reactivity in hydrogenation of alkenes and alkynes. Organometallics 2021, 40, 3617-26.

51. Borowski, A. F.; Sabo-Etienne, S.; Christ, M. L.; Donnadieu, B.; Chaudret, B. Versatile reactivity of the bis(dihydrogen) complex RuH2(H2)2(PCy3)2 toward functionalized olefins: olefin coordination versus hydrogen transfer via the stepwise dehydrogenation of the phosphine ligand. Organometallics 1996, 15, 1427-34.

52. Borowski, A. F.; Sabo-Etienne, S.; Chaudret, B. Homogeneous hydrogenation of arenes catalyzed by the bis(dihydrogen) complex [RuH2(H2)2(PCy3)2]. J. Mol. Catal. A. Chem. 2001, 174, 69-79.

53. Borowski, A. F.; Vendier, L.; Sabo-Etienne, S.; Rozycka-Sokolowska, E.; Gaudyn, A. V. Catalyzed hydrogenation of condensed three-ring arenes and their N-heteroaromatic analogues by a bis(dihydrogen) ruthenium complex. Dalton. Trans. 2012, 41, 14117-25.

54. Dobereiner, G. E.; Nova, A.; Schley, N. D.; et al. Iridium-catalyzed hydrogenation of N-heterocyclic compounds under mild conditions by an outer-sphere pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7547-62.

55. Anker, M. D.; Hill, M. S.; Lowe, J. P.; Mahon, M. F. Alkaline-earth-promoted CO homologation and reductive catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 10009-11.

56. Shi, X.; Qin, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, J. Super-bulky penta-arylcyclopentadienyl ligands: isolation of the full range of half-sandwich heavy alkaline-earth metal hydrides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 4356-60.

57. Jin, R.; Li, G.; Sharma, S.; Li, Y.; Du, X. Toward active-site tailoring in heterogeneous catalysis by atomically precise metal nanoclusters with crystallographic structures. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 567-648.

58. Zhao, S.; Jin, R.; Jin, R. Opportunities and challenges in CO2 reduction by gold- and silver-based electrocatalysts: from bulk metals to nanoparticles and atomically precise nanoclusters. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2018, 3, 452-62.

59. Gross, E.; Somorjai, G. A. Mesoscale nanostructures as a bridge between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis. Top. Catal. 2014, 57, 812-21.

60. Sun, C.; Teo, B. K.; Deng, C.; et al. Hydrido-coinage-metal clusters: rational design, synthetic protocols and structural characteristics. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 427, 213576.

61. Chiu, T. H.; Liao, J. H.; Silalahi, R. P. B.; Pillay, M. N.; Liu, C. W. Hydride-doped coinage metal superatoms and their catalytic applications. Nanoscale. Horiz. 2024, 9, 675-92.

62. Sun, C.; Mammen, N.; Kaappa, S.; et al. Atomically precise, thiolated copper-hydride nanoclusters as single-site hydrogenation catalysts for ketones in mild conditions. ACS. Nano. 2019, 13, 5975-86.

63. Liu, C. Y.; Liu, T. Y.; Guan, Z. J.; et al. Dramatic difference between Cu20H8 and Cu20H9 clusters in catalysis. CCS. Chem. 2024, 6, 1581-90.

64. Ni, Y. R.; Pillay, M. N.; Chiu, T. H.; et al. Controlled shell and kernel modifications of atomically precise Pd/Ag superatomic nanoclusters. Chemistry 2023, 29, e202300730.

65. Yuan, S. F.; Guan, Z. J.; Wang, Q. M. Identification of the active species in bimetallic cluster catalyzed hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 11405-12.

66. Liu, C. Y.; Yuan, S. F.; Wang, S.; Guan, Z. J.; Jiang, D. E.; Wang, Q. M. Structural transformation and catalytic hydrogenation activity of amidinate-protected copper hydride clusters. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2082.

67. Kulkarni, V. K.; Khiarak, B. N.; Takano, S.; et al. N-heterocyclic carbene-stabilized hydrido Au24 nanoclusters: synthesis, structure, and electrocatalytic reduction of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 9000-6.

68. Gao, Z. H.; Wei, K.; Wu, T.; et al. A heteroleptic gold hydride nanocluster for efficient and selective electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 5258-62.

69. Tang, L.; Luo, Y.; Ma, X.; et al. Poly-hydride [AuI7(PPh3)7H5](SbF6)2 cluster complex: structure, transformation, and electrocatalytic CO2 reduction properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202300553.

70. Brocha Silalahi, R. P.; Jo, Y.; Liao, J. H.; et al. Hydride-containing 2-electron Pd/Cu superatoms as catalysts for efficient electrochemical hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202301272.

71. Chen, H.; Gao, P.; Liu, Z.; et al. Direct detection of reactive gallium-hydride species on the Ga2O3 surface via solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 17365-75.

72. Wang, M.; Zheng, L.; Wang, G.; et al. Spinel nanostructures for the hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol and hydrocarbon chemicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 14528-38.

73. Chen, L.; Cooper, A. C.; Pez, G. P.; Cheng, H. On the mechanisms of hydrogen spillover in MoO3. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2008, 112, 1755-8.

74. Xi, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, H. Mechanism of hydrogen spillover on WO3(001) and Formation of HxWO3 (x = 0.125, 0.25, 0.375, and

75. Khoobiar, S. Particle to particle migration of hydrogen atoms on platinum - alumina catalysts from particle to neighboring particles. J. Phys. Chem. 1964, 68, 411-2.

76. Benseradj, F.; Sadi, F.; Chater, M. Hydrogen spillover studies on diluted Rh/Al2O3 catalyst. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 2002, 228, 135-44.

77. Antonucci, P. Hydrogen spillover effects in the hydrogenation of benzene over Ptγ-Al2O3 catalysts. J. Catal. 1982, 75, 140-50.

78. Kang, H.; Zhu, L.; Li, S.; et al. Generation of oxide surface patches promoting H-spillover in Ru/(TiOx)MnO catalysts enables CO2 reduction to CO. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 1062-72.

79. Kyriakou, G.; Boucher, M. B.; Jewell, A. D.; et al. Isolated metal atom geometries as a strategy for selective heterogeneous hydrogenations. Science 2012, 335, 1209-12.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].