Heterogeneous catalytic aldehyde-water shift of benzaldehyde into benzoic acid and hydrogen

Abstract

The “aldehyde-water shift” (AWS) reaction offers a green and sustainable route for producing carboxylic acids with the concomitant release of hydrogen. However, most current AWS processes rely on homogeneous noble metal-based catalysts, facing significant challenges in the separation and recyclability of catalysts. Herein, we present the Pt nanoparticles deposited on highly defective porous CeO2 nanorods (Pt/PN-CeO2) as highly effective catalysts for the production of carboxylic acids and H2 through the AWS reaction. Isotope investigations have confirmed the occurrence of AWS by tracing the origin of the generated hydrogen with one hydrogen from aldehyde and one hydrogen from water. Further mechanism studies have illustrated that the concentration of oxygen vacancies plays a crucial role in both the activation of the C–H bond in aldehydes and the activation of water. These findings provide valuable insights for designing new catalytic systems by focusing on the construction of heterogeneous catalysts for the AWS reaction.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

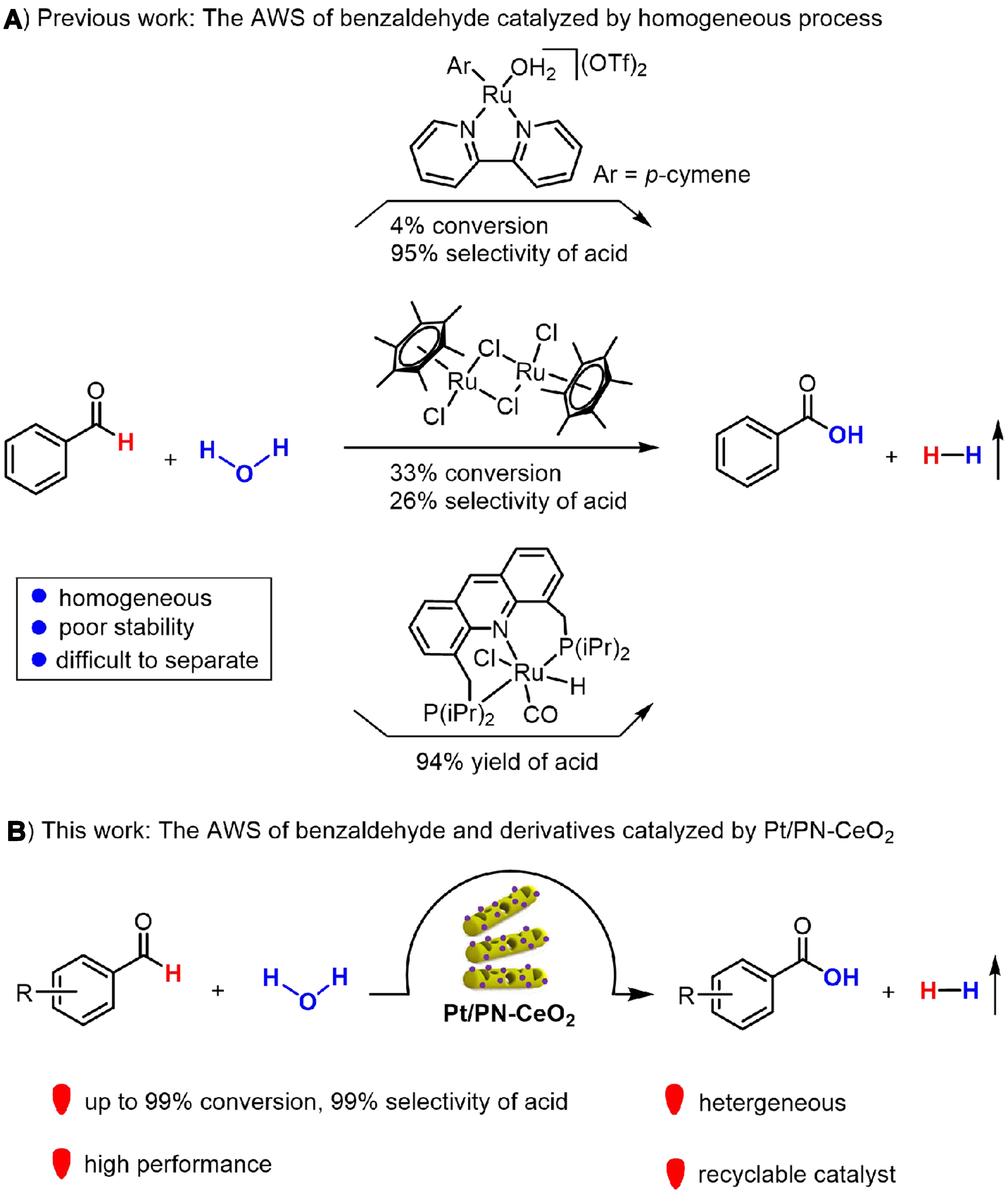

The catalytic dehydrogenation of aldehydes and water into carboxylic acids alongside hydrogen generation represents an atom-economical approach in chemical synthesis[1-9]. This transformation, known as the “aldehyde-water shift” (AWS) reaction, has garnered recognition as a green and sustainable approach for the production of various carboxylic acids[10-12]. However, the AWS reaction faces thermodynamic challenges due to the high energy nature of H2 and the high chemical stability of C–H bonds[13]. Thus, the pivotal step toward overcoming these obstacles lies in the development of highly efficient catalysts for the AWS reaction. Recently, homogeneous catalysts of metal-based complexes [e.g., iridium, rhodium, ruthenium, platinum (Pt), and copper] have demonstrated their ability to effectively initiate the AWS reaction in the presence of various additives and/or cocatalysts[14-19] [Figure 1A]. However, those homogeneous catalysts generally face two significant drawbacks: difficulty in separation and poor recyclability. Consequently, there is an urgent demand to develop high activity and stability heterogeneous catalysts for the AWS reaction. Recently, sporadic yet promising advances have been achieved in developing heterogeneous catalysts, such as copper-based metal oxide and layered double hydroxides (LDH), which have facilitated hydrogen production through the AWS reaction for several active compounds with an aldehyde group (N,N-dimethylformamide, formaldehyde, and furfural)[20-23]. The Pt/re-Mg4Al-LDHs catalysts exhibited remarkable catalytic capability for the selective oxidation of furfural into furoic acid, achieving a conversion rate of 99% and a yield of 97%[22]. In this process, the Ptδ+ sites served as the sites for adsorption and activation of the C=O bond, facilitating the production of H2. The Co@CoO heterointerface catalysts delivered a high performance of formaldehyde reforming, in which the Co and CoO components functioned as sites for the activation of C–H and O–H bonds, respectively[21]. The pursuit of highly performed heterogenous catalysts for AWS reaction, capable of producing carboxylic acid and H2, remains a highly desirable goal.

Figure 1. (A) The AWS of benzaldehyde catalyzed by homogeneous process; (B) The AWS of benzaldehyde and derivatives catalyzed by Pt/PN-CeO2. AWS: Aldehyde-water shift.

Benzoic acid, an important organic compound, has widespread applications in drug synthesis, dye production, bactericides, etc.[24-29]. Conventionally, carboxylic acids, including benzoic acid, are synthesized through oxidation of alcohol, which involved stoichiometric quantities of harsh oxidants such as acidic potassium permanganate, chromates and hydrogen peroxide[30]. However, these traditional oxidation processes often suffer from low atom economy, challenges in the post-reaction treatments, and severe environmental contamination. Consequently, there has been a concerted effort to develop catalytic oxidation routes for the production of benzoic acid, aiming for milder conditions and greater environmental compatibility[13]. Inspired by myriad advantages of AWS, the benzaldehyde water shift reaction emerges as a promising alternative to the conventional approach for the eco-friendly synthesis of benzoic acid.

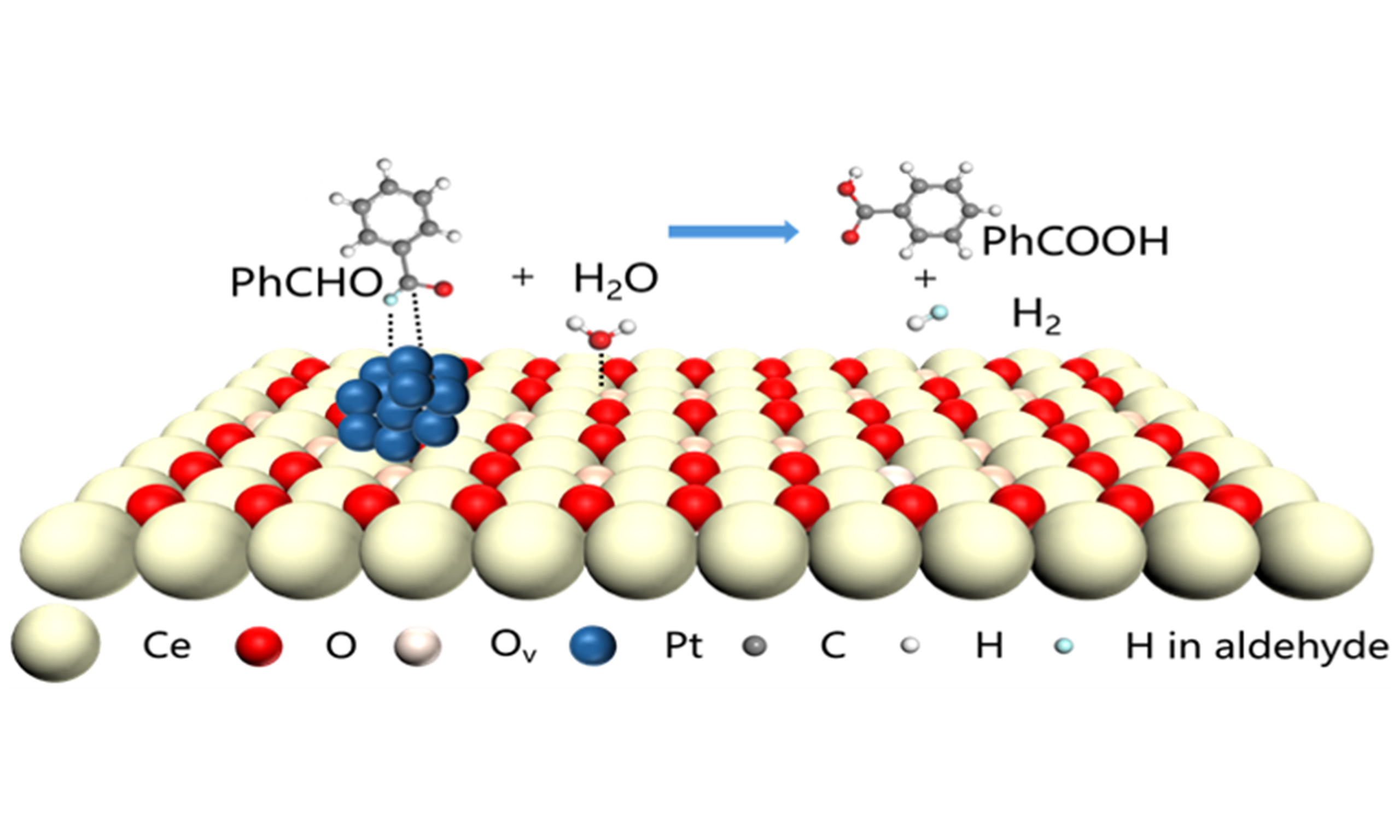

The synergistic and effective co-activation of both the C–H bond in the aldehyde group and the O–H bond in H2O are prerequisites for enhancing the performance of AWS. Inspired by the exceptional capability of Pt in activation of C–H bonds[31-33] and efficacy of defective CeO2-x in the activation of water[34-37], herein, the Pt nanoparticles deposited on highly defective porous CeO2 nanorods (Pt/PN-CeO2) have been rationally designed for the efficiently catalytic AWS reaction of benzaldehyde into benzoic acid, accompanied with the release of hydrogen with high purity [Figure 1B and Figure 2A]. Extensive investigations into the catalytic mechanism have revealed that structural defects of oxygen vacancies (Ov) play a pivotal role in enhancing the performance of Pt/PN-CeO2 for the AWS reactions. A high concentration of Ov not only facilitates the activation of water but also enhances the electron density of Pt. Consequently, this leads to improved activation of the C–H bond in aldehydes. Taking benzaldehyde as a substrate, Pt/PN-CeO2 delivered remarkable catalytic activity, achieving a benzaldehyde conversion of 99.8% and a benzoic acid selectivity of 99.6%, with a H2 yield of 85.9%. This innovative approach holds significant promise for the synthesis of benzoic acid and can be extended to catalyze a scope of aldehydes possessing a -CHO group, suggesting its versatility and potential for industrial applications.

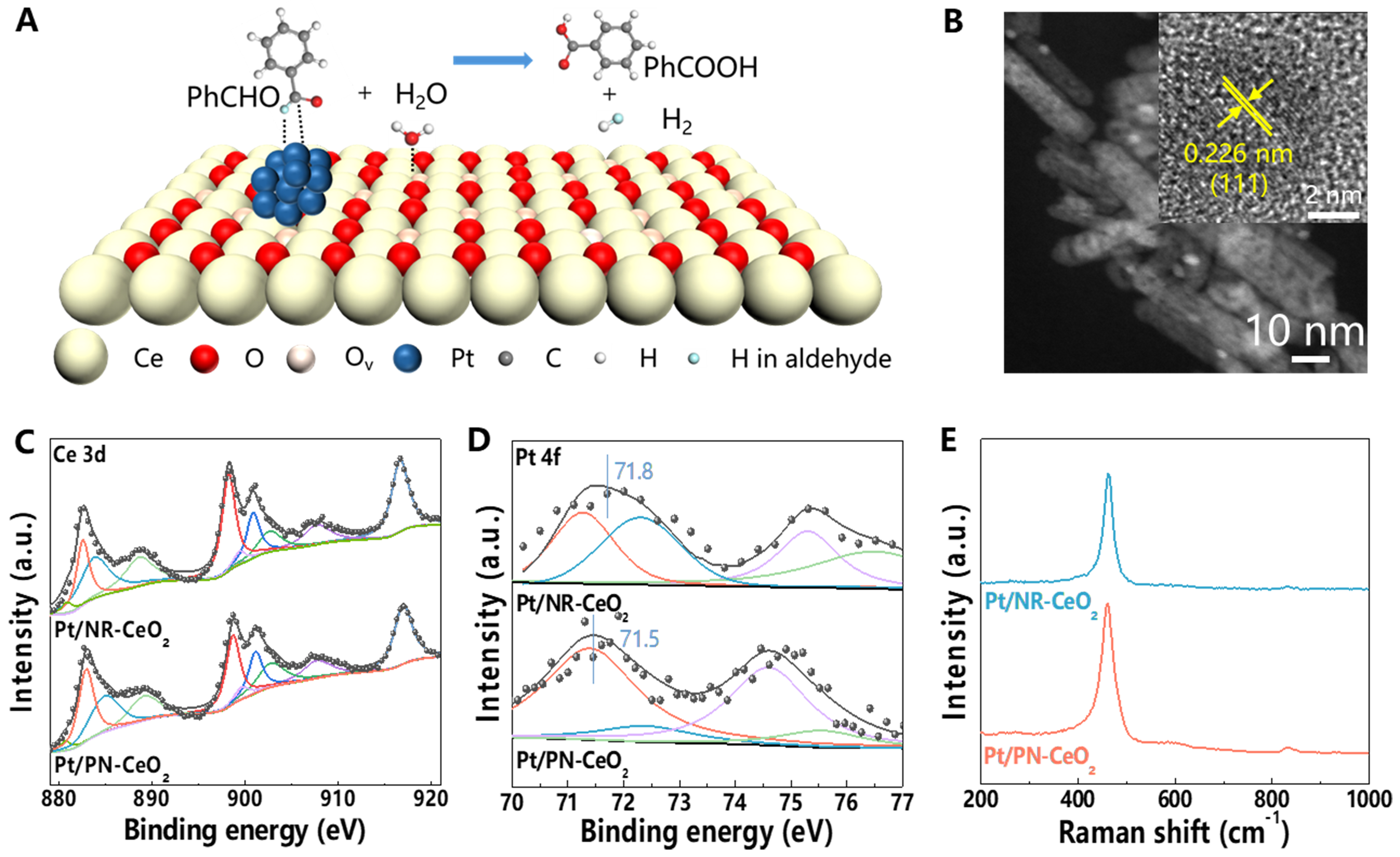

Figure 2. (A) Proposed catalytic process of the Pt/PN-CeO2 for the AWS reaction of benzaldehyde into benzoic acid and H2 at the interface between Pt and PN-CeO2; (B) Dark-field TEM of Pt/PN-CeO2 (the insert was the high-resolution dark-field TEM images); XPS analysis of (C) Ce 3d and (D) Pt 4f peaks of Pt/PN-CeO2 and Pt/NR-CeO2; (E) Raman spectra of the Pt/PN-CeO2 and Pt/NR-CeO2 catalysts. AWS: Aldehyde-water shift; TEM: transmission electron microscope; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.

EXPERIMENTAL

Preparation of catalysts

A hydrothermal approach was adopted to synthesize both nanorods of CeO2 (NR-CeO2) and porous nanorods of CeO2 (PN-CeO2). Details of the synthesis could be found in our previous reports[38,39]. Preparation of Pt/NR-CeO2 and Pt/PN-CeO2 underwent a facile impregnation method. Typically, the CeO2 supports (300 mg) were dispersed in ethanol (30 mL). Then, the desired amount of the aqueous K2PtCl4 solution was added into suspension of the CeO2. The solution was stirred for 2 h, and then evaporated at

Characterizations of catalysts

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) characterizations were performed on a JEOL2100F operated. The high angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) was performed with a FEI Tecnai F30 microscope (300 kV). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) profiles of various catalysts were analyzed by Thermo Electron Model K-Alpha. The loadings of Pt in various catalysts were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). The Raman spectra were acquired from an Alpha300R micro-confocal Raman spectrometer.

Catalytic AWS reaction

First, 30 mg of catalysts and 1 mmol of benzaldehyde were mixed in a solution of 1, 4-dioxane (1 mL) and H2O (0.5 mL) in the presence of various amounts of strong base NaOH. The reaction solution was degassed by bubbling N2 in a 30 mL autoclave. Then, 0.5 MPa of N2 was inflated in the autoclave. The temperature of the reaction system quickly increased to 180 °C. After the catalytic reaction was performed for 10 h, the reactor was allowed to cool naturally. A gas sampling bag was used to collect the gas, which was tested by gas chromatography (GC) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD, North Point GC 901A). Benzaldehyde, benzoic acid, and benzyl alcohol were detected using liquid chromatography (LC, Fuli LC 5090).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis and characterizations of catalysts

NR-CeO2 and PN-CeO2 were successfully synthesized through hydrothermal methods, as illustrated in our previous reports. The XRD patterns of both NR-CeO2 and PN-CeO2 clearly revealed a well-defined cubic fluorite structure of as-synthesized nanostructures [Supplementary Figure 1]. Dark-field TEM images displayed the nanorod-like characteristics of NR-CeO2 and the porous nanorod-like characteristics of PN-CeO2, respectively [Supplementary Figure 2A and B]. High-resolution TEM images of NR-CeO2 and PN-CeO2 [Supplementary Figure 2C and D] exhibited that the predominant crystal face in both NR-CeO2 and PN-CeO2 was CeO2(110)[40]. Analysis of the XPS profiles indicated a significantly higher surface Ce3+ fraction in PN-CeO2 (29.2%) over that in NR-CeO2 (19.8%), suggesting PN-CeO2 owned higher levels of structural defects of Ov [Supplementary Figure 3], aligning with our previous findings.

Subsequently, Pt nanoparticles with a theoretical loading of 2.0 wt.% were deposited onto the PN-CeO2 and NR-CeO2 via an impregnation process, yielding Pt/PN-CeO2 and Pt/NR-CeO2. As analyzed by ICP-OES, the actual Pt contents in Pt/NR-CeO2 and Pt/PN-CeO2 were 1.86 wt.% and 1.89 wt.%, respectively. Dark-field TEM images [Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure 4] revealed that the sizes of Pt nanoparticles on Pt/NR-CeO2 and Pt/PN-CeO2 were about 2.15 and 1.83 nm, respectively. XRD patterns of Pt/NR-CeO2 and Pt/PN-CeO2 remained similar to the phase of CeO2, indicating the preserved cubic fluorite structure of CeO2 during the synthesis process [Supplementary Figure 1]. Notably, no distinct XRD diffraction peaks for Pt were observed, attributable to the low loadings of Pt in the catalysts.

XPS and Raman spectroscopic analysis were used to further investigate surface properties of Pt/CeO2. Specifically, compared to Pt/NR-CeO2 (Ce3+ fraction of 20.9% and Ce3+-O fraction of 26.4%), Pt/PN-CeO2 displayed a significantly higher fraction of Ce3+ (30.7%) and Ce3+-O (44.5%), signifying a high concentration of Ov in Pt/PN-CeO2 [Figure 2C and Supplementary Figure 5]. Further delving into the electronic structures of Pt in these catalysts, XPS analysis of Pt 4f orbitals revealed a lower binding energy for Pt/PN-CeO2, suggesting a stronger metal-support interaction[39,41,42] [Figure 2D]. This strengthened interaction correlated with a higher proportion of Pt0 in Pt/PN-CeO2 (77.5%) as opposed to 68.6% in Pt/NR-CeO2.

To complement these findings, Raman spectroscopy was used to assess the level of Ov in Pt/CeO2 [Figure 2E]. The prominent peak at 460 cm-1 was attributed to the vibrational mode of the CeO2 fluorite structure, while the weaker peak around 600 cm-1 can be attributed to the Ov[43]. By calculating the peak area ratio of A600/A460[44], it was evident that Pt/PN-CeO2 exhibited a higher value of 0.12 compared to 0.05 for Pt/NR-CeO2, definitively demonstrating a higher level of structural defects of Ov in Pt/PN-CeO2.

Catalytic performance

The AWS reaction of benzaldehyde was selected as a model reaction to investigate catalytic behaviors of Pt/CeO2 catalysts. Initially, we optimized the molar ratio of benzaldehyde to H2O, along with the types and amounts of bases, while keeping the temperature at 180 °C and the N2 pressure at 0.5 MPa [Supplementary Tables 1-3]. When 30 mg of Pt/PN-CeO2 was used as the catalyst, the optimal conditions for the AWS reaction of benzaldehyde were found to be: 1 mmol of benzaldehyde as the substrate, 2.5 mmol of NaOH, a solvent mixture of 1,4-dioxane (1 mL) and H2O (0.5 mL), a temperature of 180 °C, and a pressure of

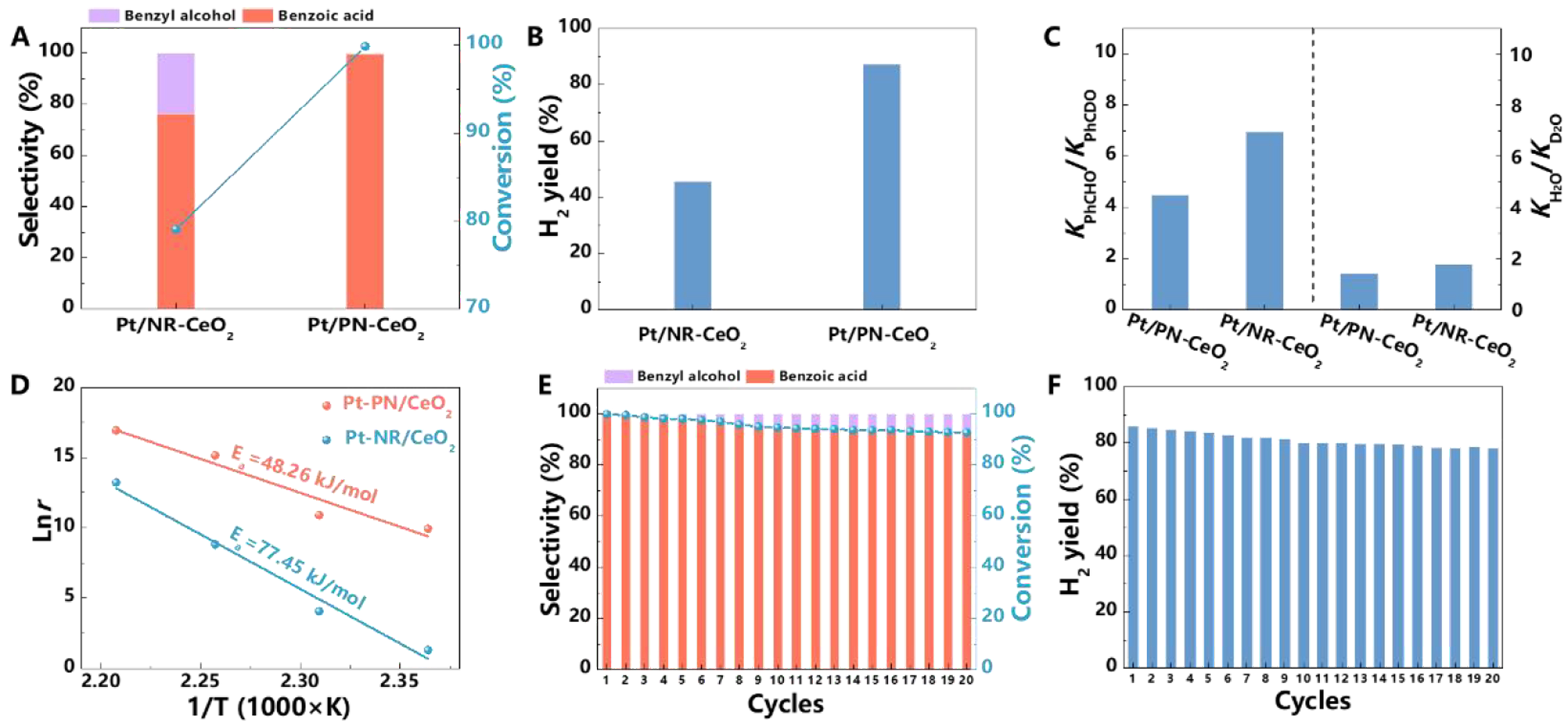

Figure 3. Catalytic performance of Pt/PN-CeO2 and Pt/NR-CeO2 for the AWS of benzaldehyde. (A) Conversions of benzaldehyde and selectivity of benzyl alcohol and benzoic acid; (B) H2 yields; (C) Ratios of H2 generation rates from PhCHO to PhCDO as well as the ratios of H2 generation rates from H2O to D2O; (D) Lnr, derived from the H2 generation rate versus reaction time, as a function of 1/T over various catalysts; (E) and (F) Catalytic stability of the Pt/PN-CeO2 catalysts for the AWS reaction. Reaction conditions for (A), (B), (D), (E) and (F): PhCHO (1 mmol), H2O (0.5 mL), 1, 4-dioxane (1 mL), NaOH (2.5 mmol), catalysts (30 mg), 0.5 MPa N2, 180 °C and

Kinetic investigations

Previously, Pt has been widely acknowledged as an effective catalyst for the activation of the C–H bonds[45,46]. Generally, the catalytic performance of metals can be significantly determined by their electronic structures. When the AWS reaction of benzaldehyde was performed under the optimal conditions, Pt/NR-CeO2 with a 1.86 wt.% Pt loading delivered a much lower catalytic performance with a benzaldehyde conversion of 79.0%, a benzoic acid selectivity of 76.3% and a hydrogen yield of 39.1% [Figure 3A and B]. This can be attributed to the relatively lower electron density of Pt nanocatalysts on NR-CeO2 than that of Pt on PN-CeO2 [Figure 2D]. To further examine the roles of Pt nanocatalysts, H/D isotope experiments of benzaldehyde were conducted [Figure 3C]. By replacing benzaldehyde (PhCHO) with benzaldehyde-α-D (PhCDO), there was a significant decrease in both the conversions of benzaldehyde and the generation rates of H2. The value of kPhCHO/kPhCDO for Pt/NR-CeO2 was 7.0, suggesting that the C–H bond activation was a rate-determining step of AWS of benzaldehyde. In contrast, Pt/PN-CeO2 exhibited a much lower value of kPhCHO/kPhCDO of 4.5, indicating that Pt with a higher electronic density accelerated C-H cleavage.

The presence of Ov in Pt/CeO2 not only modulated electronic structures of Pt but also enhanced the activation of H2O to generate abundant surface hydroxyls, which facilitated the dehydrogenation of benzaldehyde and the production of H2. Then, H2O/D2O isotope experiments were conducted to assess contributions of Ov for water activation [Figure 3C]. When H2O was replaced with D2O, the decreased production rates of H2 were observed for various Pt/CeO2 catalysts. The value of kH2O/kD2O for Pt/PN-CeO2 was 1.4, slightly lower than that (1.8) for Pt/NR-CeO2. Comparing these values with the kPhCHO/kPhCDO ratios, it is evident that the dissociation of H2O is not a rate-determining step for AWS reaction of benzaldehyde. Lower impact of D2O on H2 generation rates for Pt/PN-CeO2 suggested that a higher surface concentration of Ov delivered a higher capacity for the H2O activation.

Next, the reaction orders (n) of two Pt/CeO2 catalysts were investigated to gain insights into their catalytic activity, particularly examining how the substrate coverage at active sites affected the performance of catalysts[47,48]. The positive n values[49] with respect to benzaldehyde further implied that activation of C–H bond in benzaldehyde was kinetically relevant step in AWS reaction, typically occurring on the Pt surface. A low value of n generally indicates the kinetical difficulty for the accessibility of reactants to catalyst surface. Herein, Pt/PN-CeO2 (0.91) exhibited a higher n value compared to Pt/NR-CeO2 (0.85) at the similar Pt loading, demonstrating the better accessibility and catalytic activity of Pt/PN-CeO2 for the benzaldehyde substrate [Supplementary Figure 6].

Kinetic analysis was then conducted to assess intrinsic catalytic capabilities of Pt/CeO2 for the AWS reaction at different reaction temperatures. The experiments were conducted within a temperature range of 150 and 180 °C, ensuring that benzaldehyde conversions remained below 30% for all measurements [Figure 3D]. Reaction rate constant r was calculated from slope of the H2 generation rates at various reaction temperatures. Activation energy Ea was determined by slope of linear fit between logarithm of reaction rate constant (Lnr) and the reciprocal of the absolute temperature (1/T). The derived Ea value of Pt/PN-CeO2 was 48.3 kJ·mol-1, lower than that of Pt/NR-CeO2 (77.4 kJ·mol-1) [Figure 3D]. This indicated that Pt/PN-CeO2 possessed a higher capability for catalyzing the AWS of benzaldehyde compared to Pt/NR-CeO2, as a lower Ea generally corresponded to a more favorable reaction pathway and faster reaction rates.

Catalytic stability

Longer-term stability was conducted [Figure 3E and F]. Even after twenty cycles, there was only a slight decrease in benzaldehyde conversion, benzoic acid selectivity, and H2 yield, demonstrating the high catalytic stability of the catalysts. After the long-term cycling, there was a reduction in the surface Ce3+ fraction to 29.8% along with a lower Ce3+-O fraction of 40.4% for the used Pt/PN-CeO2 catalysts [Supplementary Figure 7A and B], compared to as-synthesized catalysts (a Ce3+ fraction of 30.7% and a Ce3+-O fraction of 44.5%). Considering the pivotal role of Ov, the slight decline in activity and selectivity could potentially be attributed to minimal catalyst loss, along with a slight reduction in the structural defects associated with Ov. Additionally, morphology, phase and surface properties of the spent Pt/PN-CeO2 remained well-preserved [Supplementary Figure 7C-E], further confirming the structural robustness of the catalysts.

Catalytic mechanism

Based on the analysis provided, both Pt nanoparticles and Ov play crucial roles in activation of the C–H bond and H2O. Catalytic activities of Pt/CeO2 are influenced by varying concentrations of Ov. As shown in Figure 2D, the higher fraction of Pt0 in Pt/PN-CeO2 suggested the increased electronic density of the Pt nanoparticles. The strong electronic metal-support interaction between Pt nanoparticles and PN-CeO2 constructed more Ptδ--Ov-Ce3+ interfacial sites, which was supported by the high concentration of surface defects (a high Ce3+ fraction of 30.7% and a large Ce3+-O fraction of 44.5%) in Pt/PN-CeO2. The Ptδ--Ov-Ce3+ interfacial sites are active for the C-H dehydrogenation via heterolytic cleavage, according to previous reports[50-52]. Moreover, defective CeO2 has been reported to facilitate H2O dissociation[34,36,38], leading to the production of a greater amount of reactive oxygen species, resulting in the acceleration of aldehyde oxidation on Pt/PN-CeO2.

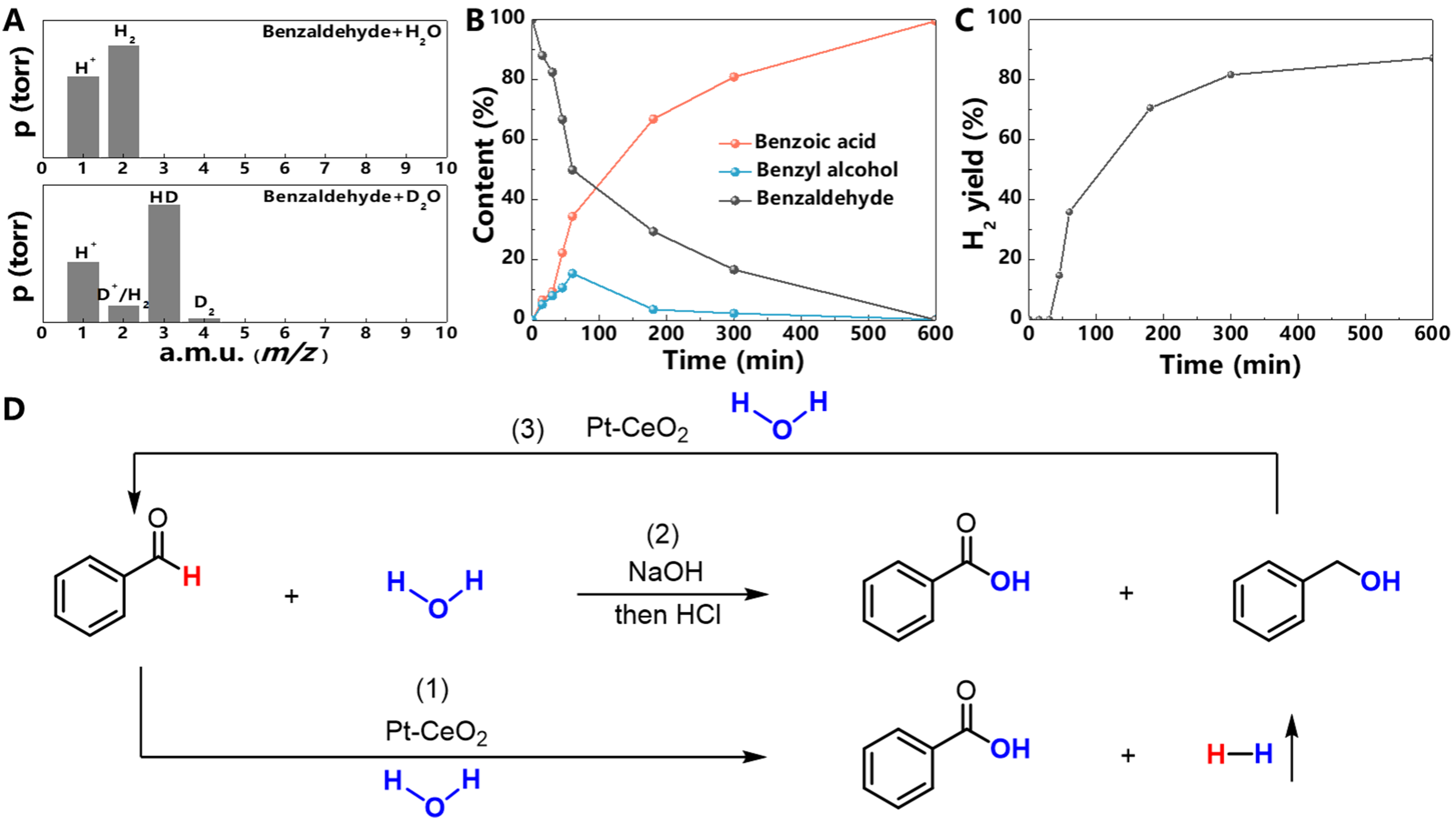

Then, to gain insight into the catalytic mechanism, the isotope experiments were carried out to confirm the origin of H2 production. By substituting H2O with D2O, gaseous and liquid products were analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance hydrogen spectroscopy (1H NMR), respectively. When H2O was used, MS signals of generated gas were observed at m/z values of 2 and 1, corresponding to H2 and H+, respectively [Figure 4A]. Comparatively, when D2O was utilized, the multiple MS signals were observed at m/z values ranging from 1 and 4, indicating the involvement of water in the AWS reaction. Notably, the dominant HD peak unambiguously suggested that two H atoms in the generated H2 originated from water and benzaldehyde, respectively. Additionally, the MS signal at the m/z value of 4 was observed due to the H/D exchange between benzaldehyde and D2O. The 1H NMR profile of liquid products after the AWS reaction between H2O and benzaldehyde gave a signal at approximately 12.3 ppm, which could be assigned to the

Figure 4. Catalytic mechanism. (A) MS analysis of H2 generated in the Pt/PN-CeO2/H(D)2O/benzaldehyde systems; (B) Distributions of reactants and products of the AWS of benzaldehyde catalyzed by Pt/PN-CeO2 at intervals during a period of 10 h; (C) H2 evolution profile with a time from the reaction mixture; (D) The illustration of benzaldehyde oxidation, benzyl alcohol oxidation, and the disproportionation of aldehyde over the Pt/PN-CeO2 catalysts. Reaction conditions: PhCHO (1 mmol), H2O/D2O (0.5 mL), 1, 4-dioxane (1 mL), NaOH (2.5 mmol), catalysts (30 mg), 180 °C and 10 h. MS: Mass spectrometry; AWS: aldehyde-water shift.

In principle, the AWS reaction involves one benzaldehyde molecule and one H2O molecule to produce one benzoic acid molecule and one H2 molecule. However, the observed H2 yields for all catalysts were below this ideal scenario. To understand this phenomenon, both the liquid and gaseous products were monitored at intervals [Figure 4B and C]. Alongside the benzaldehyde dehydrogenative coupling with water to generate benzoic acid and H2, the disproportionation of benzaldehyde also occurred to produce benzoic acid and benzyl alcohol. The disproportionation of benzaldehyde led to a quick consumption of aldehyde during the initial stage [Figure 4B]. As depicted in Figure 4C, no release of H2 was observed during the initial 30 min, indicating a silent period of the AWS reaction and a dominance of the aldehyde disproportionation reaction at the early stage. As anticipated, benzoic acid and benzyl alcohol were detected in a ratio close to 1:1, strongly indicating the occurrence of benzaldehyde disproportionation [Supplementary Figure 9A and B]. Even in the absence of a catalyst under the same conditions, an equimolar amount of benzoic acid and benzyl alcohol was generated, further confirming the benzaldehyde disproportionation under the reaction conditions [Supplementary Figure 9C and D]. Afterward, the generated benzyl alcohol from disproportionation of benzaldehyde was gradually consumed and more benzoic acid was progressively produced, accompanied by the generation of H2. The results strongly suggested the occurrence of aqueous-phase reforming of benzyl alcohol and H2O. To validate this, aqueous-phase reforming of benzyl alcohol and H2O was conducted under the same catalytic conditions as the AWS reaction, in which benzaldehyde was replaced by benzyl alcohol. The production of benzoic acid and H2 further confirmed the occurrence of this reforming reaction [Supplementary Figure 10].

Based on the aforementioned control experiments, the catalytic AWS reaction of benzaldehyde was outlined as follows [Figure 4D]:

(1) Disproportionation reaction during the initial stage. Benzaldehyde undergoes a predominantly disproportionation reaction under basic catalytic conditions, leading to the formation of benzyl alcohol and benzoic acid [step (2)];

(2) AWS reaction. Following the initial disproportionation, benzaldehyde then undergoes an AWS reaction, yielding benzoic acid and H2 [step (1)];

(3) Concurrent reforming of benzyl alcohol. Simultaneously, the benzyl alcohol generated from the initial disproportionation reaction reacts with H2O in an aqueous-phase reforming process, consuming the benzyl alcohol and producing additional benzoic acid and H2 [step (3)].

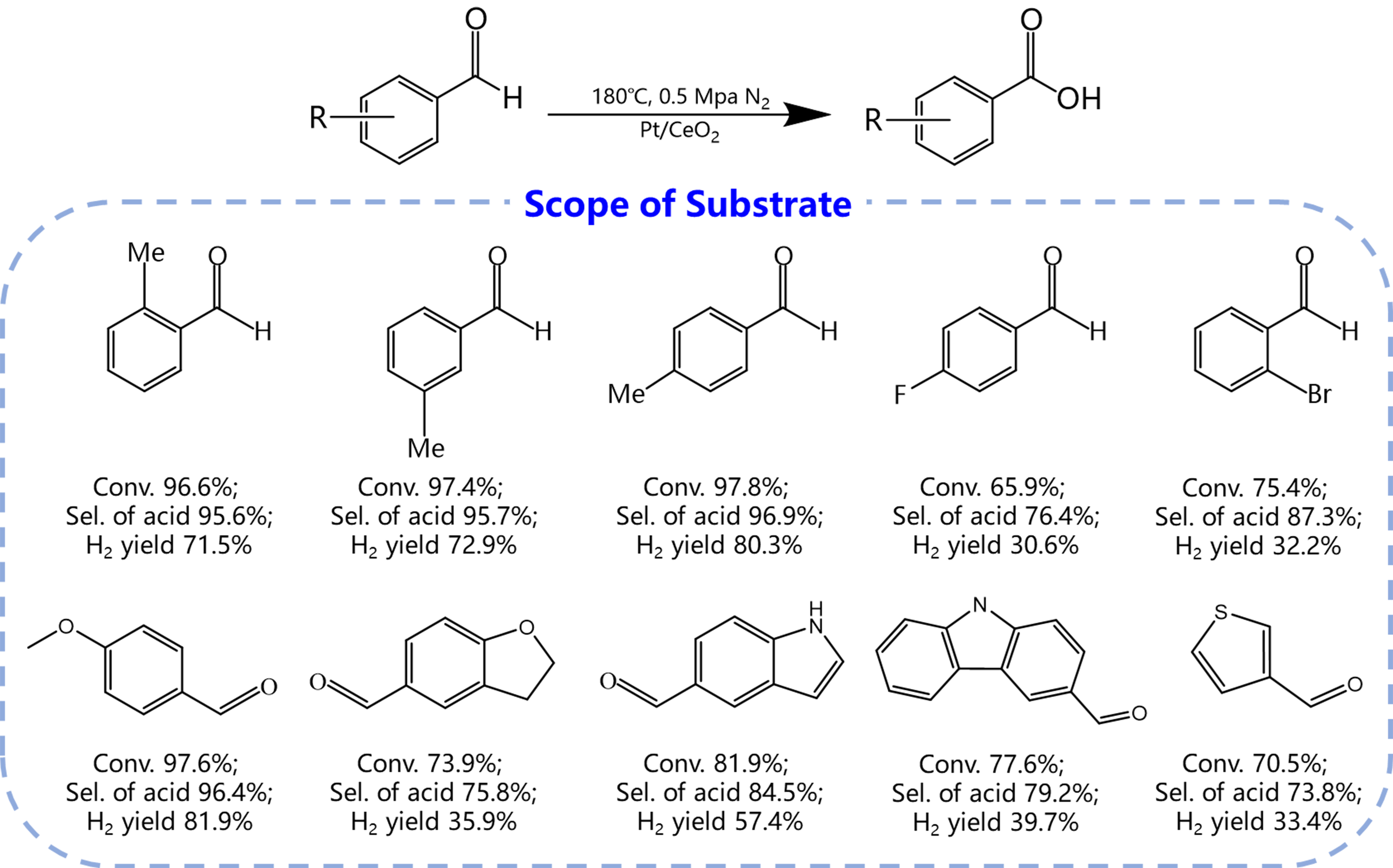

Catalytic scope

The AWS reactions could be extended to various benzaldehyde derivatives. Under the same catalytic conditions, these derivatives undergo reactions with H2O to produce the corresponding acids with the release of H2 [Figure 5]. Notably, the methyl-substituted benzaldehydes achieved high conversion, selectivity and H2 yields. However, benzaldehyde derivatives substituted with electron-withdrawing groups (such as F- and Br-) on the benzene ring displayed moderated activity and selectivity and H2 fields.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the Pt/PN-CeO2 catalysts have proven to be highly efficient heterogeneous catalysts for AWS reaction, which successfully converts aldehydes and H2O into carboxylic acids and H2. The monitoring of the reaction process indicated that the catalytic reaction initially involved the disproportionation of aldehydes, followed by the domination of the AWS reactions, leading to an unsatisfactory H2 yield. Isotope experiments unveiled the H2 generation with one H atom from aldehyde and another H atom from water, experimentally demonstrating occurrence of the AWS reaction. Abundant Ov in Pt/PN-CeO2 concurrently enhances water activation and boosts electron density of the anchored Pt catalysts, thereby facilitating improved C–H bond activation in aldehydes. This study offers an alternative method for synthesis of carboxylic acids through a green and sustainable approach, demonstrating its potentials for practical applications.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Designed the experiments, conducted characterization, analyzed data, interpreted results, drew the pictures, and wrote the manuscript: Meng, X.; Yan, B.; Cao, F.; Qu, Y.

Synthesized samples: Meng, X.; Yan, B.

Contributed to helpful discussions and provided material support: Qi, Z.; Xie, M.; Ma, Y.

Directed and supervised the project and revised the manuscript: Cao, F.; Qu, Y.

Availability of data and materials

The experimental data and associated test results are available in the Supplementary Materials of this article.

Financial support and sponsorship

We acknowledge the support from Xi’an Yiwei Putai Environmental Protection Co., LTD and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (D5000210829; D5000210601).

Conflicts of interest

Qi, Z. and Xie, X. are affiliated with Xi’an Yiwei Putai Environmental Protection Co., LTD. The other authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Balaraman, E.; Khaskin, E.; Leitus, G.; Milstein, D. Catalytic transformation of alcohols to carboxylic acid salts and H2 using water as the oxygen atom source. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 122-5.

2. Gellrich, U.; Khusnutdinova, J. R.; Leitus, G. M.; Milstein, D. Mechanistic investigations of the catalytic formation of lactams from amines and water with liberation of H2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4851-9.

3. Liu, D.; Zhou, C.; Wang, G.; et al. Active Pd nanoclusters supported on nitrogen/amino co-functionalized carbon for highly efficient dehydrogenation of formic acid. Chem. Synth. 2023, 3, 24.

4. Sun, Z.; Zhao, H.; Yu, X.; Hu, J.; Chen, Z. Glucose photorefinery for sustainable hydrogen and value-added chemicals coproduction. Chem. Synth. 2024, 4, 4.

5. Truong-Phuoc, L.; Essyed, A.; Pham, X.; et al. Catalytic methane decomposition process on carbon-based catalyst under contactless induction heating. Chem. Synth. 2024, 4, 56.

6. Hu, P.; Ben-David, Y.; Milstein, D. General synthesis of amino acid salts from amino alcohols and basic water liberating H2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 6143-6.

7. Hu, P.; Diskin-Posner, Y.; Ben-David, Y.; Milstein, D. Reusable homogeneous catalytic system for hydrogen production from methanol and water. ACS. Catal. 2014, 4, 2649-52.

8. Khusnutdinova, J. R.; Ben-David, Y.; Milstein, D. Oxidant-free conversion of cyclic amines to lactams and H2 using water as the oxygen atom source. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2998-3001.

9. Nielsen, M.; Alberico, E.; Baumann, W.; et al. Low-temperature aqueous-phase methanol dehydrogenation to hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Nature 2013, 495, 85-9.

10. Brewster, T. P.; Goldberg, J. M.; Tran, J. C.; Heinekey, D. M.; Goldberg, K. I. High catalytic efficiency combined with high selectivity for the aldehyde–water shift reaction using (para-cymene)ruthenium precatalysts. ACS. Catal. 2016, 6, 6302-5.

11. Brewster, T. P.; Ou, W. C.; Tran, J. C.; et al. Iridium, rhodium, and ruthenium catalysts for the “aldehyde–water shift” reaction. ACS. Catal. 2014, 4, 3034-8.

12. Phearman, A. S.; Moore, J. M.; Bhagwandin, D. D.; Goldberg, J. M.; Heinekey, D. M.; Goldberg, K. I. (Hexamethylbenzene)Ru catalysts for the aldehyde-water shift reaction. Green. Chem. 2021, 23, 1609-15.

13. Kar, S.; Milstein, D. Oxidation of organic compounds using water as the oxidant with H2 liberation catalyzed by molecular metal complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 2304-15.

14. Alberico, E.; Sponholz, P.; Cordes, C.; et al. Selective hydrogen production from methanol with a defined iron pincer catalyst under mild conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013, 52, 14162-6.

15. Fujita, K.; Tamura, R.; Tanaka, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Onoda, M.; Yamaguchi, R. Dehydrogenative oxidation of alcohols in aqueous media catalyzed by a water-soluble dicationic iridium complex bearing a functional N-heterocyclic carbene ligand without using base. ACS. Catal. 2017, 7, 7226-30.

16. Gunanathan, C.; Ben-David, Y.; Milstein, D. Direct synthesis of amides from alcohols and amines with liberation of H2. Science 2007, 317, 790-2.

17. Pitman, C. L.; Brereton, K. R.; Miller, A. J. Aqueous hydricity of late metal catalysts as a continuum tuned by ligands and the medium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2252-60.

18. Sarbajna, A.; Dutta, I.; Daw, P.; et al. Catalytic conversion of alcohols to carboxylic acid salts and hydrogen with alkaline water. ACS. Catal. 2017, 7, 2786-90.

19. Zweifel, T.; Naubron, J. V.; Grützmacher, H. Catalyzed dehydrogenative coupling of primary alcohols with water, methanol, or amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009, 48, 559-63.

20. Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, S.; Ma, Y. Base-free hydrogen generation from formaldehyde and water catalyzed by copper nanoparticles embedded on carbon sheets. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 783-8.

21. Qian, K.; Yan, Y.; Xi, S.; et al. Elucidating the strain-vacancy-activity relationship on structurally deformed Co@CoO nanosheets for aqueous phase reforming of formaldehyde. Small 2021, 17, e2102970.

22. Ren, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Pt atomic clusters catalysts with local charge transfer towards selective oxidation of furfural. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2021, 295, 120290.

23. Zhang, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Qu, Y. Additive-free, robust H2 production from H2O and DMF by dehydrogenation catalyzed by Cu/Cu2O formed in situ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 8245-9.

24. Fu, K.; Dong, L.; Liu, P.; et al. Immobilized enzymatic alcohol oxidation as a versatile reaction module for multienzyme cascades. Chem. Synth. 2023, 3, 49.

25. Libanori, M.; Santos, G.; Pereira, S.; et al. Organic benzoic acid modulates health and gut microbiota of Oreochromis niloticus. Aquaculture 2023, 570, 739409.

26. Xiao, C.; Zhang, L.; Hao, H.; Wang, W. High selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzylaldehyde and benzoic acid with surface oxygen vacancies on W18O49/holey ultrathin g-C3N4 nanosheets. ACS. Sustainable. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 7268-76.

27. Yang, X.; Sun, R. Progress in transition-metal-catalyzed synthesis of benzo-fused oxygen- and nitrogen heterocyclic compounds from benzoic acids. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023, 365, 124-41.

28. Zheng, C.; He, G.; Xiao, X.; et al. Selective photocatalytic oxidation of benzyl alcohol into benzaldehyde with high selectivity and conversion ratio over Bi4O5Br2 nanoflakes under blue LED irradiation. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2017, 205, 201-10.

29. Zhu, L.; Luo, Y.; He, Y.; et al. Selective catalytic synthesis of bio-based high value chemical of benzoic acid from xylan with Co2MnO4@MCM-41 catalyst. Mol. Catal. 2022, 517, 112063.

30. Wang, L.; Tang, R.; Kheradmand, A.; et al. Enhanced solar-driven benzaldehyde oxidation with simultaneous hydrogen production on Pt single-atom catalyst. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2021, 284, 119759.

31. Sattler, A.; Paccagnini, M.; Lanci, M. P.; Miseo, S.; Kliewer, C. E. Platinum catalyzed C–H activation and the effect of metal–support interactions. ACS. Catal. 2020, 10, 710-20.

32. Sun, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Pt enhanced C–H bond activation for efficient and low-methane-selectivity hydrogenolysis of polyethylene over alloyed RuPt/ZrO2. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. Energy. 2024, 353, 124046.

33. Zeitler, H. E.; Phearman, A. S.; Gau, M. R.; Carroll, P. J.; Cundari, T. R.; Goldberg, K. I. Metal-ligand-anion cooperation in C-H bond formation at platinum(II). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 14446-51.

34. Rodriguez, J. A.; Ma, S.; Liu, P.; Hrbek, J.; Evans, J.; Pérez, M. Activity of CeOx and TiOx nanoparticles grown on Au(111) in the water-gas shift reaction. Science 2007, 318, 1757-60.

35. Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Luo, Q.; et al. Two-dimensional manganese oxide on ceria for the catalytic partial oxidation of hydrocarbons. Chem. Synth. 2022, 2, 2.

36. Fu, Q.; Saltsburg, H.; Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. Active nonmetallic Au and Pt species on ceria-based water-gas shift catalysts. Science 2003, 301, 935-8.

37. Zhang, S.; Xia, Z.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qu, Y. Spatial intimacy of binary active-sites for selective sequential hydrogenation-condensation of nitriles into secondary imines. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3382.

38. Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ma, Y.; Hu, J.; Qu, Y. Sustainable production of hydrogen with high purity from methanol and water at low temperatures. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5527.

39. Zhang, S.; Xia, Z.; Ni, T.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Qu, Y. Strong electronic metal-support interaction of Pt/CeO2 enables efficient and selective hydrogenation of quinolines at room temperature. J. Catal. 2018, 359, 101-11.

40. Mai, H. X.; Sun, L. D.; Zhang, Y. W.; et al. Shape-selective synthesis and oxygen storage behavior of ceria nanopolyhedra, nanorods, and nanocubes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005, 109, 24380-5.

41. Montini, T.; Melchionna, M.; Monai, M.; Fornasiero, P. Fundamentals and catalytic applications of CeO2-based materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 5987-6041.

42. Vivier, L.; Duprez, D. Ceria-based solid catalysts for organic chemistry. ChemSusChem 2010, 3, 654-78.

43. Lee, J.; Ryou, Y.; Chan, X.; Kim, T. J.; Kim, D. H. How Pt interacts with CeO2 under the reducing and oxidizing environments at elevated temperature: the origin of improved thermal stability of Pt/CeO2 compared to CeO2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016, 120, 25870-9.

44. Zhang, S.; Chang, C. R.; Huang, Z. Q.; et al. High catalytic activity and chemoselectivity of sub-nanometric Pd clusters on porous nanorods of CeO2 for hydrogenation of nitroarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2629-37.

45. Haneda, M.; Watanabe, T.; Kamiuchi, N.; Ozawa, M. Effect of platinum dispersion on the catalytic activity of Pt/Al2O3 for the oxidation of carbon monoxide and propene. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2013, 142-3, 8-14.

46. Karp, E. M.; Silbaugh, T. L.; Crowe, M. C.; Campbell, C. T. Energetics of adsorbed methanol and methoxy on Pt(111) by microcalorimetry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 20388-95.

47. Garetto, T.; Rincón, E.; Apesteguı́a, C. Deep oxidation of propane on Pt-supported catalysts: drastic turnover rate enhancement using zeolite supports. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2004, 48, 167-74.

48. Kang, L.; Liu, X. Y.; Wang, A.; et al. Photo-thermo catalytic oxidation over a TiO2-WO3-supported platinum catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 12909-16.

49. Liu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Qu, Y. Strong metal-support interactions between Pt and CeO2 for efficient methanol decomposition. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 146219.

50. Du, E.; Yang, J.; Huai, L.; et al. Quantifying interface-dependent active sites induced by strong metal–support interactions on Au/TiO2 in 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan oxidation. ACS. Catal. 2025, 15, 54-62.

51. Liao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Feng, X.; et al. Defective Auδ--Ov interfacial sites boost C-H bond activation for enhanced selective oxidation of amino alcohols to amino acids. J. Catal. 2024, 429, 115284.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].