Fluorescent organic cages and their applications

Abstract

Organic cages are an emerging subclass of crystalline porous materials with structural tunability, modularity, and processibility, having exhibited potential in applications such as molecular recognition, gas adsorption, catalysis, and other fields. Fluorescence can be easily introduced into organic cages by incorporating fluorescent building blocks. The diversity of fluorescent building blocks and well-developed cage construction methods allowed the booming of fluorescent organic cages. More importantly, incorporating fluorescent properties into organic cages can further expand their application areas, especially in fields such as biological imaging and luminescent devices. The cavity of organic cages endows them with extra confined space to accommodate bioactive species or drugs compared to fluorescent small molecules. Compared to their framework counterparties, organic cages with well-characterized structures exhibit better processability, allowing their use in applications beyond solutions. In this review, we summarize the latest progress on fluorescent organic cages, focusing on their construction methods and the recent advances in their applications.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The fluorescence phenomenon in organic molecules, including traditional fluorescence and thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF)[1], involves the emission of light as molecules transition radiatively from excited electronic states to their ground singlet states, typically associated with luminophores possessing large π-conjugated systems[2]. Beyond their study in small molecular forms, these fluorogens have been integrated into more complex systems such as polymers, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)[3,4], covalent organic frameworks (COFs)[5], organic cages, etc. The construction of larger fluorescent entities is one of the solutions to address the detrimental effects of solvents and local environments on fluorogen emission performance. For example, too flexible fluorophores, which strongly interact with solvents in solutions, would cause a non-radiative process competing with fluorescent emissions, and thus should be restricted in more rigid structures to maintain fluorescence, a phenomenon related to aggregation-induced emission (AIE)[6]. Conversely, planar fluorophores in aggregated states can lead to aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ), and arranging fluorescent groups in a non-parallel fashion may enhance fluorescent quantum yields in solid states. The assembly of fluorogens into versatile fluorescent structures enables a wider range of applications, such as drug carriers with sensing capabilities. These carriers require suitable cavities for drug transport, a feature that fluorescent small molecules alone cannot provide.

Among the hierarchical fluorescent structures (MOFs, COFs, polymers, etc.), organic cages constitute a distinct class of purely organic porous materials, notable for their discrete cage-like geometries with regular, adjustable, and soluble molecular pore structures[7-10]. The unique solubility advantage of organic cages is comparable to that of small fluorescent molecules, which, along with the tuneable pores in organic cages that provide more ordered and customizable cavities than polymers, facilitates the selective capture and transport of guest molecules. Additionally, diverse construction strategies for organic cages allow for the strategic arrangement of fluorescent groups within organized structures to modulate fluorescence properties effectively.

Propelled by advancements in fluorescence analytical technology and expanding application demands, fluorescent organic cages have emerged as a significant research focus in recent years[11-13]. For instance, these cages function effectively as sensors that selectively capture and detect target analytes[13]. In terms of bio-related applications, they serve as biocompatible probes for non-invasive cell tracking and live imaging[14], and as intelligent drug carriers equipped with real-time drug efficacy monitoring capabilities[15]. Additionally, they hold promise as functional materials in disease diagnosis and treatment[16]. Moreover, fluorescent organic cages are being explored as high-efficiency luminous devices for photoelectric conversion[17].

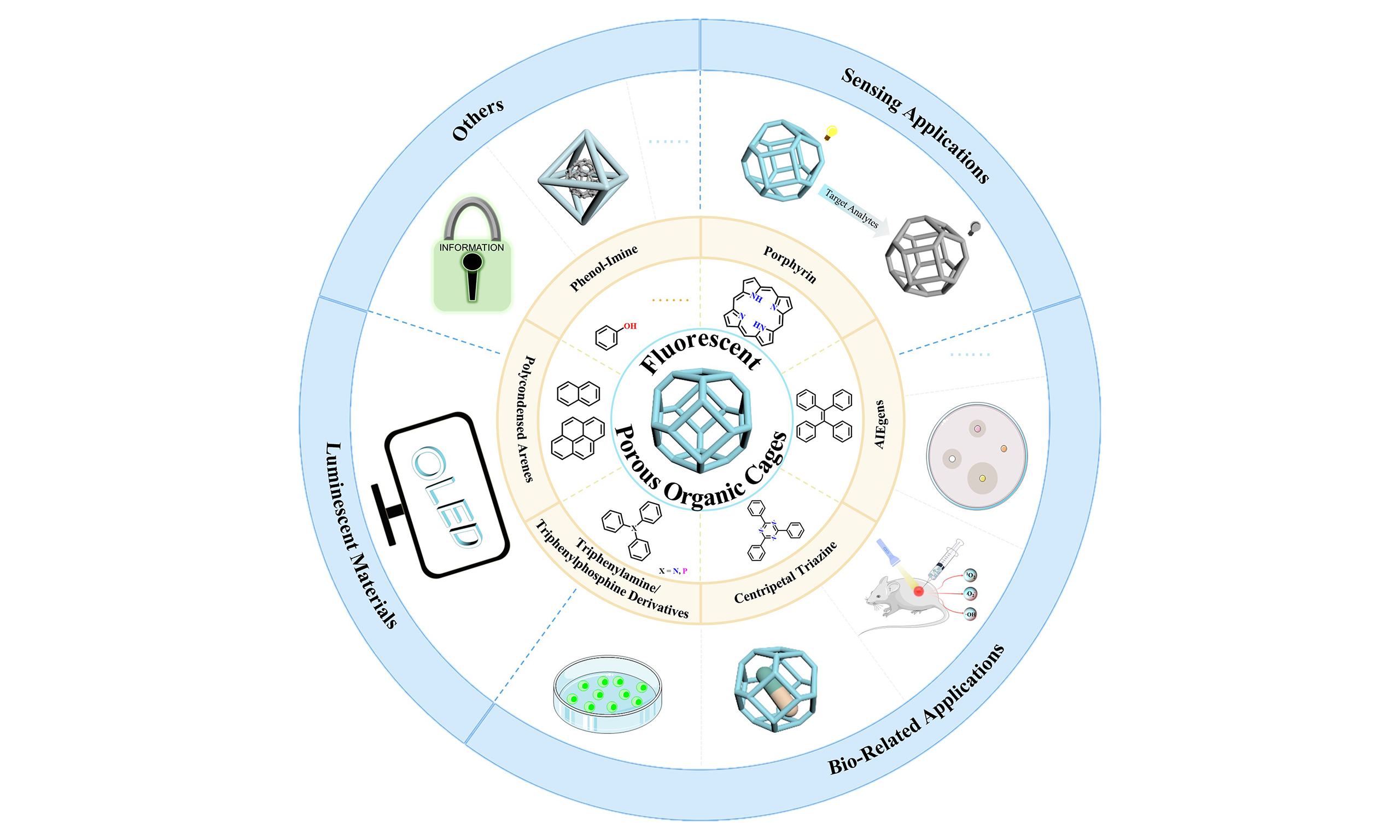

Despite a few reviews on fluorescent porous materials and their applications[18-21], comprehensive summaries specifically focusing on fluorescent organic cages are still missing. This paper aims to highlight the design and synthesis strategies of fluorescent organic cages and, more importantly, their recent application cases. We hope the structure-property relationship that could be extracted from the case studies will provide guidance for the design of new fluorescent organic cages or, more broadly, fluorescent porous materials in the future [Figure 1].

SYNTHESIS STRATEGIES OF FLUORESCENT ORGANIC CAGES

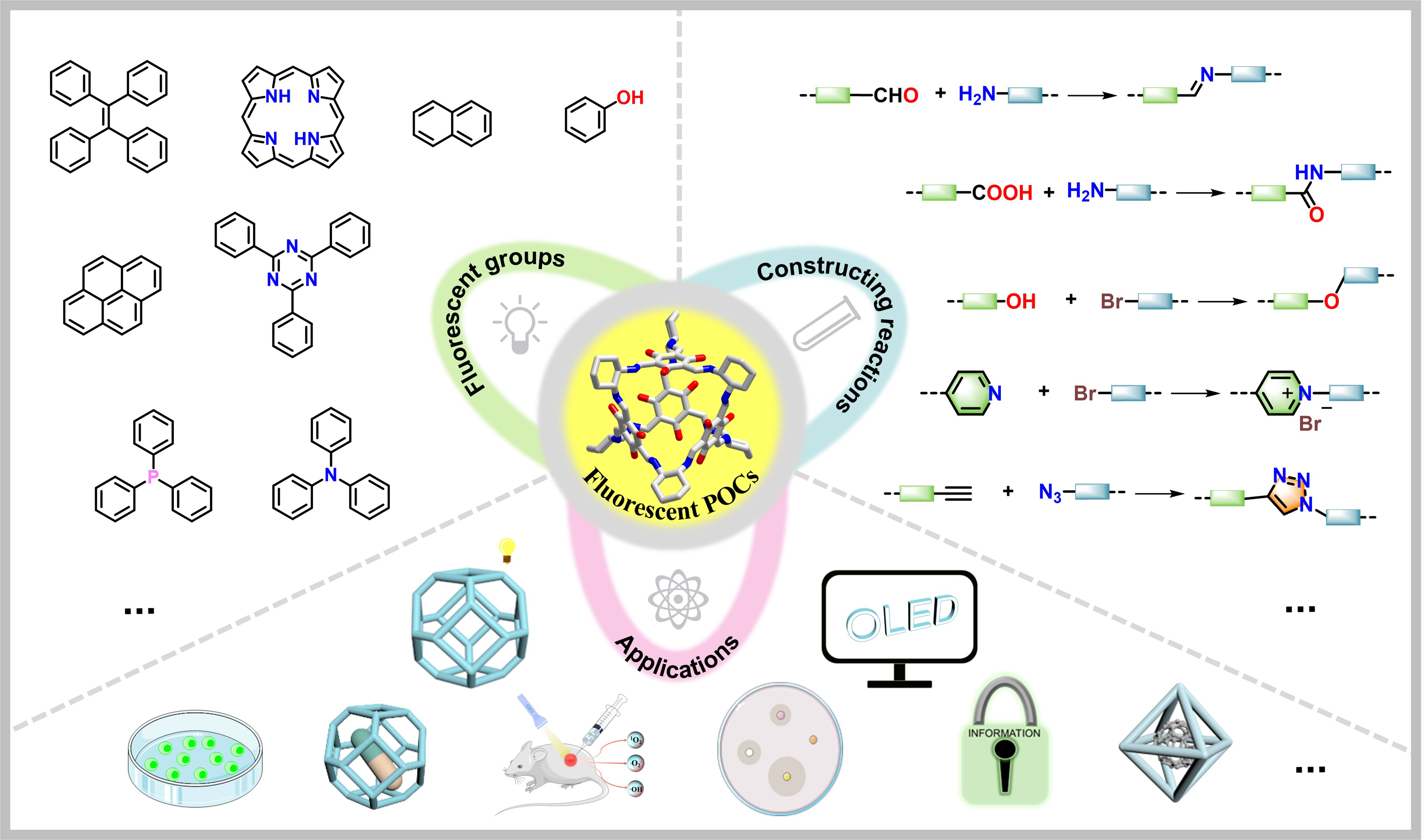

Most fluorogens, which could be activated to emit fluorescence, are π-conjugated systems[2]. For some conjugated planar structures such as naphthalene, pyrene, porphyrin, etc., the inherent rigidity of these structures facilitates high electron delocalization capability, ensuring a high probability for ground state energy level transition to excited state transitions and the subsequent π* → π radiative relaxation[5]. For TADF to occur, corresponding molecular structures generally have charge transfer[22] and stronger spin–orbit coupling. Heteroatoms such as N or O involved could promote suitable energy gaps between excited singlet (electrons are all paired) and triplet (with unpaired electrons) states[1] in the molecular system, as the unbonded electrons on the heteroatoms offer much finer molecular energy levels compared with non-heteroatomic systems, which increases the possibility of singlet-triplet transitions. Typically, designing and preparing organic cages with fluorescence involves incorporating a series of luminescent structural units and manipulating molecular conjugation and charge transfer in the cage structure. However, a simple structure-property relationship could not summarize all the fluorescent emission phenomena, as not only the molecular structure but also molecular packing or environment would affect the light-emitting behaviors of the studied systems[2]. Thus, the generation and the mechanism of the light emissions for the fluorescent organic cages would not be discussed in detail in this review; they have already been covered in other reviews[2,23,24]. Instead, this section will focus on summarizing the fluorescent groups used to construct organic cages and the methods by which they are connected.

Most fluorescent groups are ideal for preparation of organic cages due to their rigid nature, and choices of groups to functionalize fluorogens determine the subsequent cage-forming reaction types. Common synthetic approaches for organic cages including irreversible linking chemistry (e.g., nucleophilic substitution reactions) and dynamic covalent chemistry (DCC, e.g., imine condensations) could all work for the synthesis of fluorescent organic cages[7,25-28]. Notably, molecular cages constructed from conjugated bonding, such as -N=C-, -C=C, imidazolium groups, etc., feature extended π-conjugated structures that facilitate the light excitation process. The topology of organic cages received, represented briefly by [x+y] (x and y are stoichiometric numbers in the cage formation chemical equation), is determined inherently by the reaction sites and quantity of corresponding precursors involved. As topology is closely relevant to the size and geometry of organic cages, its effects on the corresponding fluorescence properties of these cages are cast in several aspects. On the one hand, the fluorescence quantum efficiency of organic cages could be tuned through the cage size, and the influences of cage geometry on their crystal packing would affect the fluorescent properties in the solid states, such as the AIE behavior. On the other hand, controlling the topology offers an approach to customize the selectivity of a fluorescent organic cage over guest molecules, which is desirable in sensing technology[29,30].

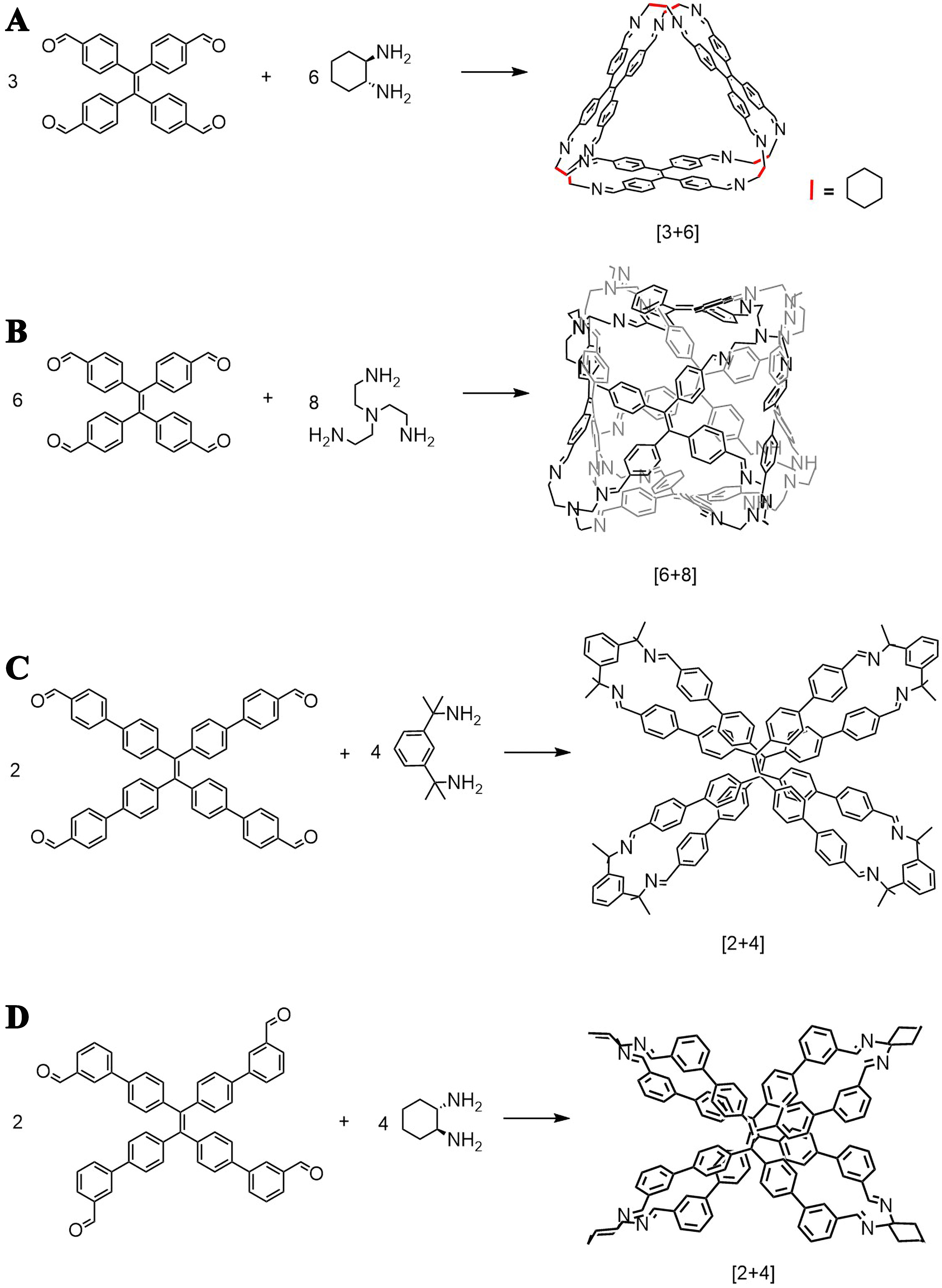

Fluorescent organic cages based on AIEgens

AIE defines a photophysical phenomenon that organic fluorophores display much-enhanced fluorescence in aggregated or solid states compared to that in solution. AIE promises immense potential for solid-state applications which would be challenging for conventional ACQ fluorophores[31,32]. The bulky substituents in the twisted propeller-like structure of AIE luminogens (AIEgens) restrict intramolecular motions and short contact of aromatic rings and thus promote AIE[2,31]. Typical AIEgens include 2,3-diphenylacrylonitrile, hexaphenylsilole, tetraphenylethylene (TPE), etc., among which TPE and its derivates have been explored most commonly in constructing fluorescent organic cages. TPE and its derivatives have a central ethylene group and four symmetric peripheral aromatic rings, whose rigidity and angular positioning make them good building blocks for construction of organic cages. Reaction sites are functionalized at the four phenyl groups, and the tetra-precursors could be fabricated into cages via dynamic reversible reaction such as imine condensation[33-35], or irreversible linking chemistry including click reaction[25], nucleophilic substitution[36-38], and so on. For imine condensations, aldehyde-functionalized TPEs are often utilized. For example, tetra-aldehyde TPE formed [3+6] imine cages with cyclodiamine

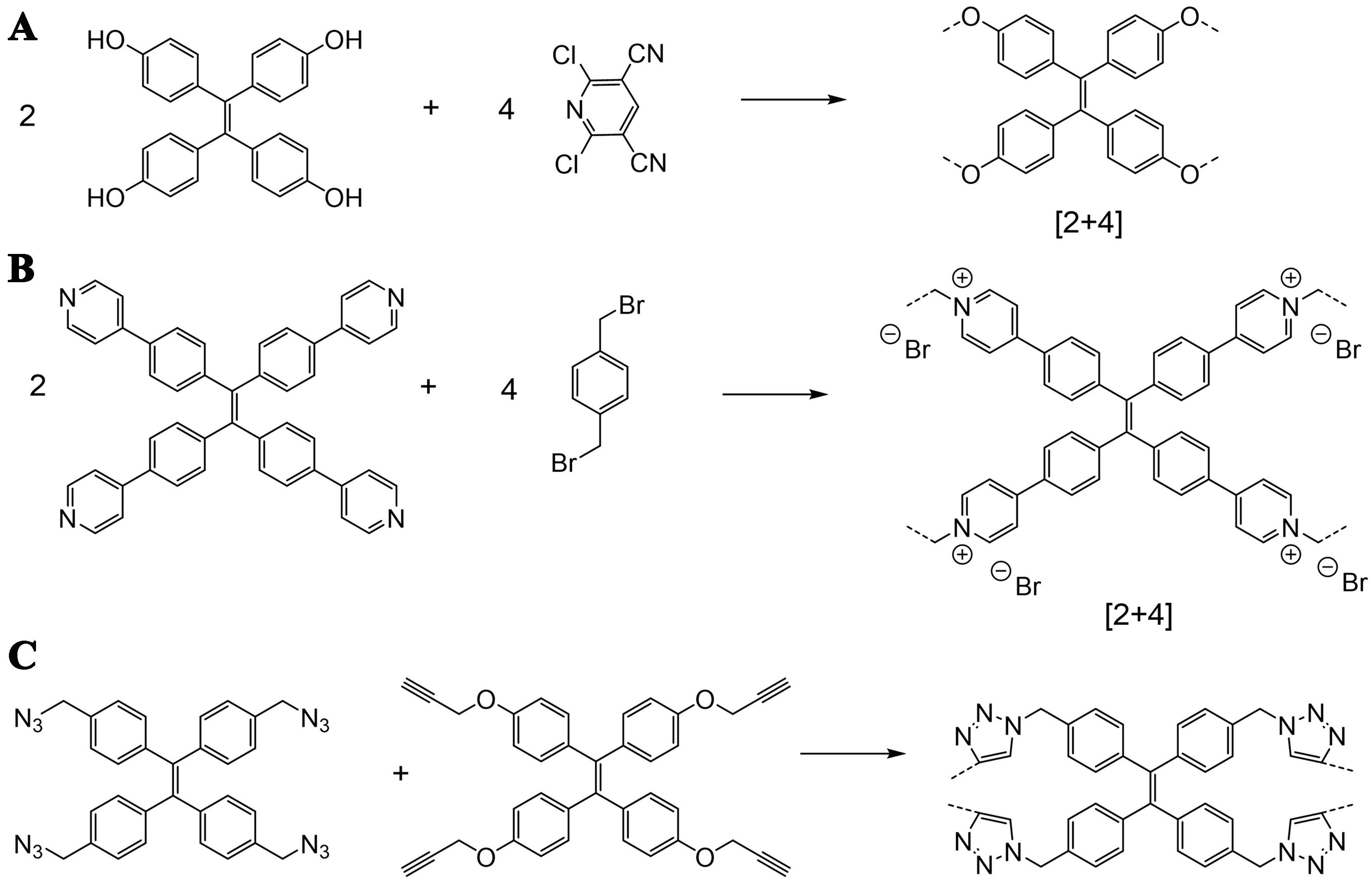

Irreversible reactions could also be utilized to construct TPE cages, which usually involve precursors including tetra-phenol TPE, tetra-pyridine TPE, tetra-azide TPE, etc. The formation of [2+4] ether-linked cages could be realized with tetra-phenol TPE and 2,6-dichloropyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile through nucleophilic aromatic substitution reaction [Figure 3A][36]. The TPE ether cage displayed fluorescence in tetrahydrofuran solution with a quantum yield of 7.8% owing to the restriction of intramolecular rotation. The quantum yield could be further improved by changing the carbonitrile groups on the phenyl ring to chloride, where a quantum yield of 26% could be shown in a toluene solution[43]. The TPE ether cages all presented enhanced fluorescence emission in aggregated states, which are typical characteristics of AIE. Tetra-pyridine TPE underwent Menshutkin reaction with dihalogen-functionalized benzene to construct [2+4] ionic pyridinium TPE cages [Figure 3B][37,38,44-49], which could present fluorescence with quantum yields of 31.0%-48.2% in solution after anion exchange and over 30% in the solid state[37]. While pyridinium cationic cages usually would undergo fluorescence quenching due to intramolecular photoinduced electron charge transfer[37], the long distance between the TPE and pyridinium group in the above-mentioned pyridinium cages impeded the quenching process and retained the fluorescent property. TPE click organic cages could be constructed through a four-fold click reaction between azide- and propargyl-functionalized TPE derivatives [Figure 3C][25]. Other sophisticated designs of TPE precursors also could be utilized to construct organic cages, such as that ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayltetrakis(benzene-4,1-diyl) tetraacrylate, a tetraethylene TPE, could undergo a thiol-Michael addition with another tetrathiol TPE, which formed a cage with two parallel units linked by four linkers[16]. The tetraphenylethene molecular cages could also be functionalized with other luminescent groups to tune their fluorescent emission, which could be manipulated to emit white light[50].

Figure 3. TPE precursors for the construction of fluorescent organic cages through irreversible reactions. TPE: Tetraphenylethylene.

Fluorescent organic cages synthesized with other AIEgens than TPE derivatives have also been reported; for instance, phenylene-diacetonitrile could be constructed to conjugated 2,3-diphenylacrylonitrile-linked organic cages with triangular prism geometry using Knoevenagel reaction with tri-aldehydes[26].

Fluorescent organic cages based on porphyrin

Porphyrin is a class of compounds with a large π-conjugated system composed of four pyrroles interconnected by methylene bridges, possessing unique biochemical properties. The planar structure of porphyrin tends to aggregate due to strong π-π stacking interaction at high concentrations[51], which would decrease fluorescent emission. Thus, synthesis of cages with porphyrin building blocks needs to arrange the porphyrin groups at a suitable distance in order to retain the fluorescence[52].

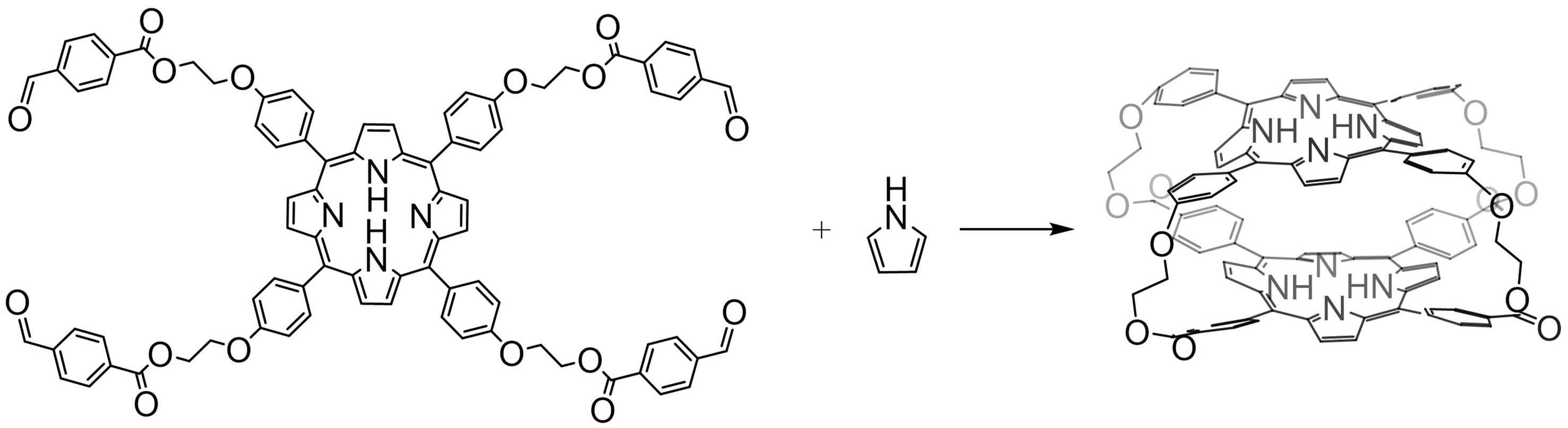

The first coplanar double porphyrin cage was reported as early as 1977[53]. A synthetic method was adapted with the Adler-Longo porphyrin condensation process of a tetra-aldehyde derivative, prepared by refluxing porphyrin tetra-aldehyde and pyrrole, which created a coplanar double porphyrin cage with four alkyl chains. Owing to the flexible link between the two porphyrins, the coplanar double porphyrin cage demonstrated adjustable three-dimensional cavities [Figure 4].

Figure 4. Synthesis of the first cofacial porphyrin cage linked with four alkyl chains[53]. Reproduced with permission, Copyright 1977, ACS.

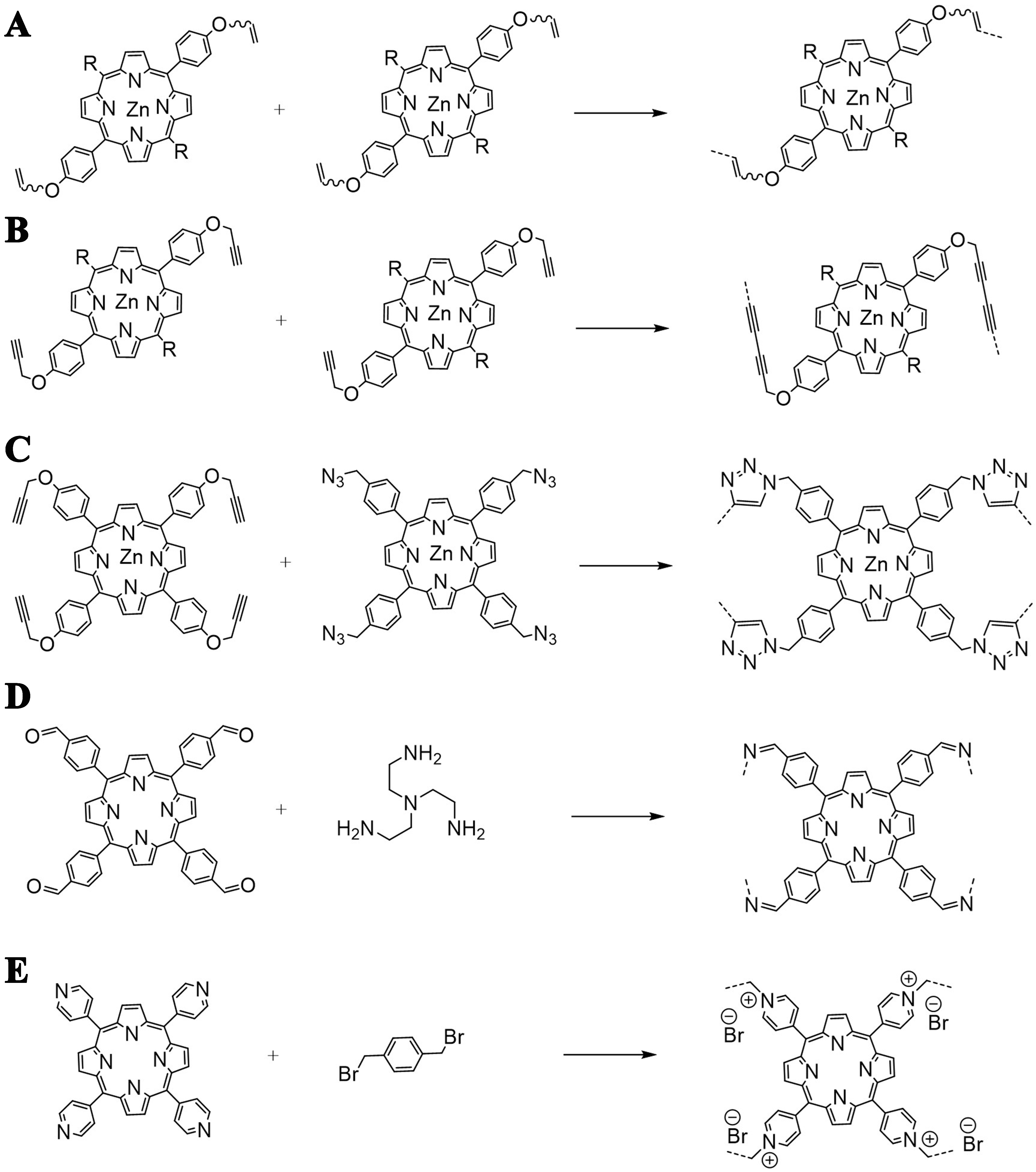

Functionalization of porphyrins with certain functional groups and subsequent reaction strategies to form cages with flexible linkers have been summarized in a review by Cen et al.[54], where template-directed methods such as olefin metathesis reactions [Figure 5A], Glaser coupling reaction [Figure 5B], or click-chemistry reaction [Figure 5C] were used. Organic cages could also be prepared by reversible imine condensations [Figure 5D][55,56], which were typically composed through linear (or bent) bidentate and triangular tridentate building units, or less reported triangular tridentate and square tetra-topic ligands. Although the fluorescence of the porphyrin cage was discovered then, this characteristic was not extensively exploited. In 2015, Hong et al. introduced the porphyrin ring as a luminescent tetra-topic ligand through imine condensation to construct two [6+8] fluorescent molecular cages, which was the first reported case of an organic cages framework being constructed through a triangular and square ligand[56]. Porphyrin cages could also be constructed through nucleophilic Menshutkin reaction [Figure 5E][31,51,57]. For example, a [2+4] cationic cage was constructed with 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(3-(bromomethyl)phenyl)porphyrin and 4,4’-bipyridine, which displayed a fluorescence quantum yield of 1.2%[58].

Fluorescent organic cages based on polycondensed arenes

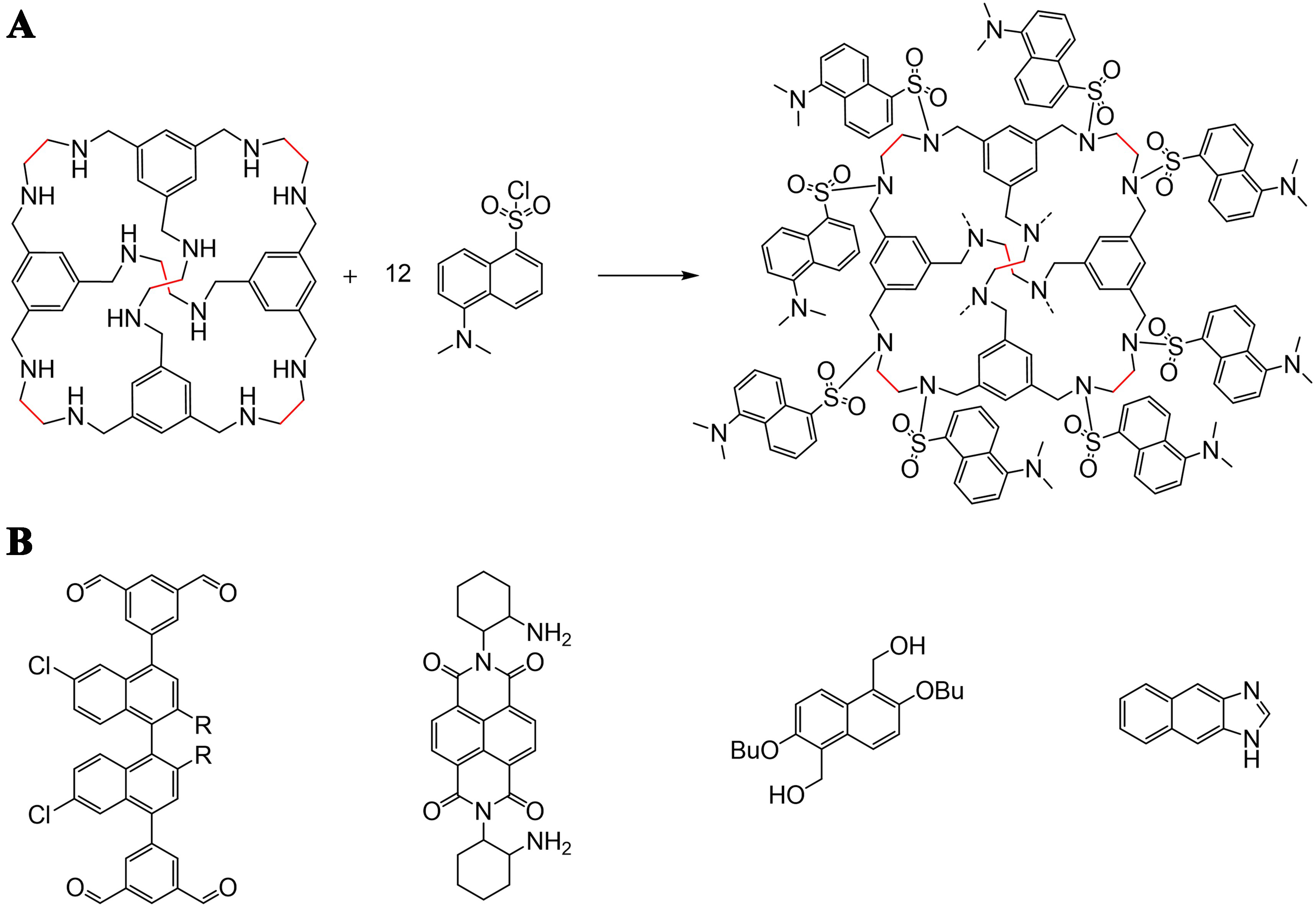

The simplest polycondensed arene is naphthalene, which has a planar conjugated structure and is a typical ACQ group[59]. Naphthalene groups emit light with a high quantum yield in dilute solution; however, the fluorescence would be quenched in an aggregated state as excimers form. One method could utilize the arrangement of the arene groups into a rigid cage molecule structure where the naphthalene groups would face different directions and avoid parallel intermolecular interaction. Sun et al. post-functionalized a reduced imine cage RCC1 through a sulfonation reaction with dansyl chloride, which gave a 3D-symmetric cage D-RCC1 anchored with 12 dansyl groups pointing differently [Figure 6A][6]. The rigid cage core impeded the interaction of the naphthalene groups and ACQ, which granted D-RCC1 fluorescent property not only in dilute solutions, but also an ultrahigh quantum yield of fluorescence emission (92%) in the solid state[6]. The naphthalene unit could also be functionalized with different functional groups for further cage closure reactions, such as naphthalene-aldehyde derivative[60], naphthalene-amine derivative[61], naphthalene-nol derivative[62,63], naphthalene-imidazole derivative[64], and so on [Figure 6B].

Figure 6. (A) Post-functionalized RCC1 with 12 dansyl groups[6]. Reproduced with permission, Copyright 2022, ACS; (B) Naphthalene derivatives.

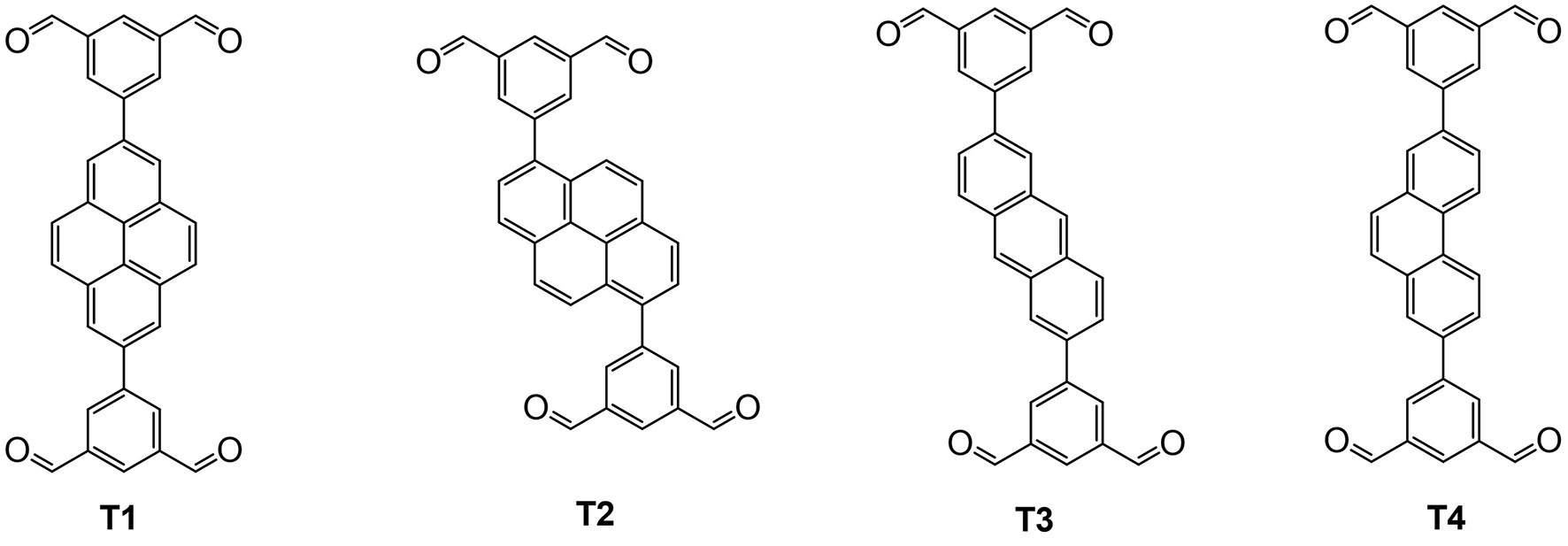

Pyrene is a planar structure consisting of four fused arene rings, which exhibit efficient fluorescence with a long emission lifetime[65]. Apart from fluorescence originating from its own conjugated π-system structure, pyrene could produce excimer emission under certain circumstances. Excimers are dimeric excited-state species, and excimer emission is fluorescence derived from intermolecular interaction just as the AIE phenomenon, which would produce a red-shift emission with a longer lifetime[2]. Pyrene groups could form a cage-like structure by co-crystallization through H-bonding with the salt component, which is more commonly known as a “pyrene box”. They also can be constructed into an organic cage through covalent bonding. For example, Sun et al. functionalized the pyrene group with four aldehydes and formed a [3+6] imine cage with six cyclohexanediamines. The C-H… π interaction between cyclohexanediamine and pyrene segments replaced the slipped π–π stacking configuration among pyrene groups, which induced a red-shift of the excitation energy of the pyrene group to the visible light region in the solid state[66]. Ge et al. synthesized a series of anthracene, phenanthrene and pyrene-based aldehydes (T1-4, Figure 7) and formed corresponding [3+6] imine cages with cyclohexanediamines[67]. These cages not only present fluorescence but also successfully exhibit circularly polarized luminescence. Other construction strategies for pyrene organic cages have also been reported, such as through Friedel-Crafts alkylation[68].

Fluorescent organic cages based on phenol-imine

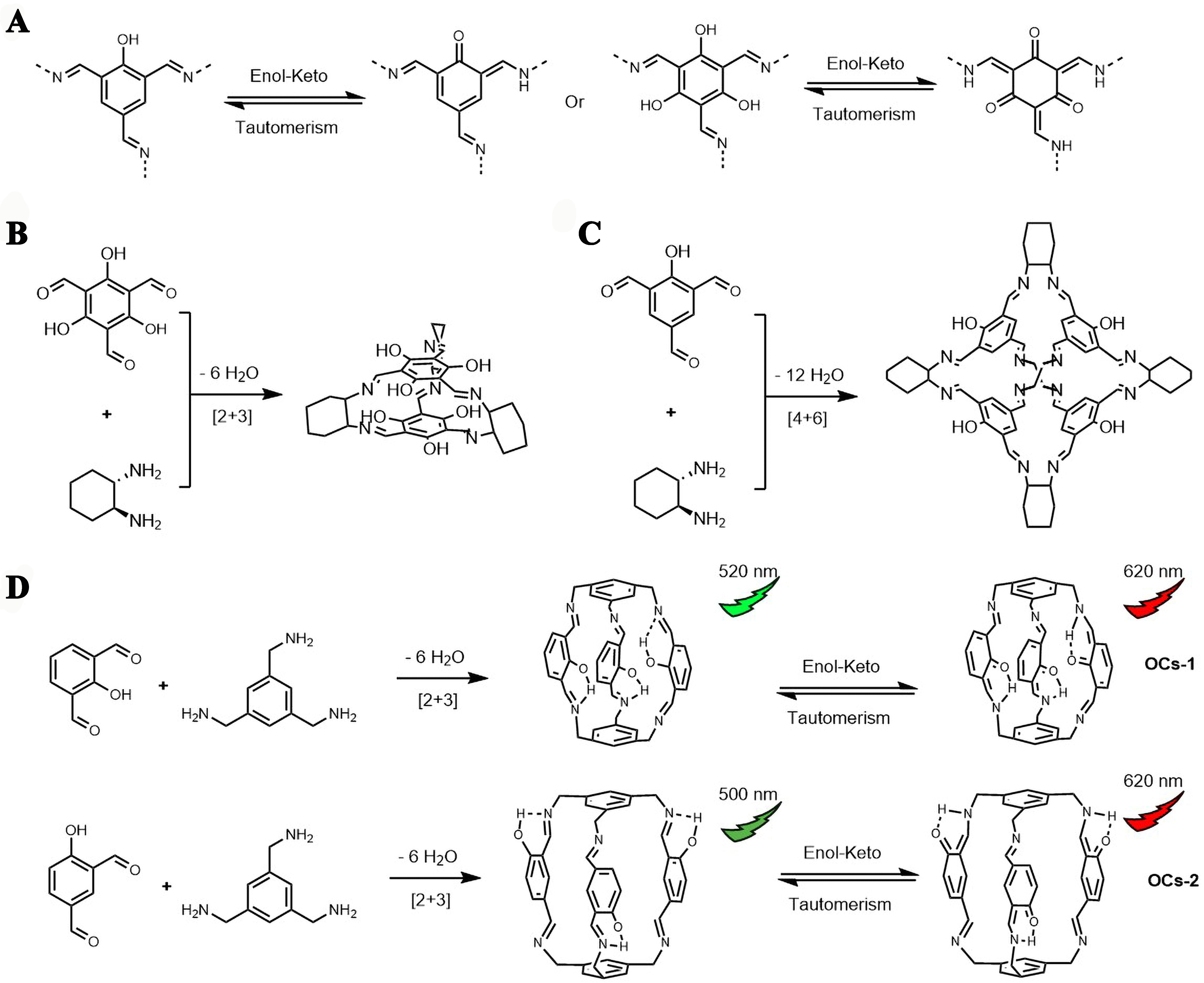

Phenol-imine systems could work as efficient fluorescent groups due to the enol-keto tautomerism [Figure 8A], which promotes the system photostability and sustains the fluorescence[69]. Thus, imine cages constructed with phenol groups display tautomeric properties and good fluorescence. For example, 2,4,6-triformyl phloroglucinol and cyclohexanediamine formed an [2+3] imine cage OC1 [Figure 8B], which displayed strong and consistent fluorescence in a dilute solution[69]. A [4+6] imine cage OC2 [Figure 8C] in the same paper constructed from 2-hydroxybenzene-1,3,5-tricarbaldehyde and cyclohexandiamine showed strong fluorescence with a quantum yield of 6.7% in dimethyl sulfoxide solution[69]. Another example of phenol-imine cages [OCs-1 and OCs-2 derived from 1,3,5-tris(aminomethyl)benzene) and 2- or 4-hydroxyisophthalaldehyde, Figure 8D] showed dual fluorescence emissions upon enol-keto tautomerism, with the keto-form emitting longer wavelength fluorescence[70]. Reduction of the imine cage gave an amine cage with improved solubility in water, which could also display fluorescence under basic conditions when the hydroxyl group on the benzene ring was deprotonated and formed phenolate ions[71,72]. Under such circumstances, coordination of phenolate with metal ions could easily occur, which induces charge transfer and fluorescence quenching. Thus, cages with phenol-imine/amine systems could work as highly sensitive and selective sensors for metal ions. Phenol-imine cage systems could also be observed in the salicylbisimine cages developed by Mastalerz et al.[73,74], though corresponding fluorescent studies on these cages were not reported, except that a porous quinoline cage transformed from one [4+6] salicylbisimine cage by a twelve-fold Povarov reaction[75]. The chemically more robust quinoline cage presented a switch of fluorescent light color from pale yellow to red upon contact with acid, which was caused by protonation on the pyridinium nitrogen atom and simultaneous disruption of the hydrogen bonding between the nitrogen and the adjacent phenol hydrogen.

Figure 8. (A) Schematic of Enol-Keto tautomerism; (B) The synthesis of OC1. Reproduced[69], Open access, Copyright 2022, RSC; (C) The synthesis of OC2. Reproduced[69], Open access, Copyright 2022, RSC; (D) Synthesis and enol-keto tautomerism of OCs-1 and OCs-2. Reproduced with permission[70], Copyright 2024, Elsevier B.V.

Fluorescent organic cages based on centripetal triazine

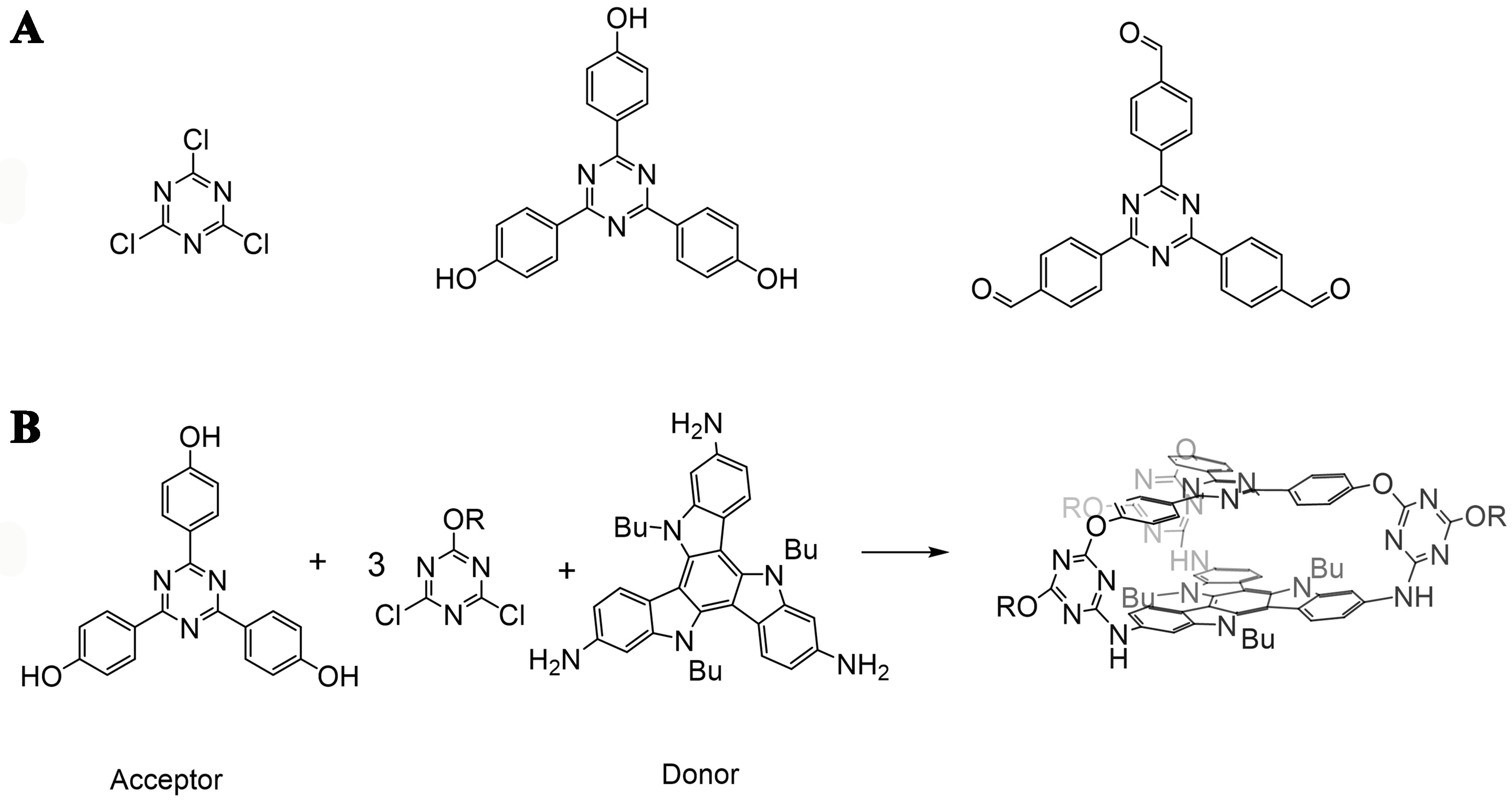

As a conjugated π-system end-capped with electron donors and acceptors (D-π-A), centripetal triazine derivatives work as useful luminescent groups for TADF through charge-transfer mechanisms[76,77]. The electron-deficient triazine group in the center serves as a symmetric electron withdrawing group, which is usually linked by three conjugated phenyl groups with electron-donating groups containing N or O atoms to work as fluorophores[77-79]. Thus, centripetal triazine derivatives are usually utilized as electron acceptor building blocks to construct fluorescent organic cages.

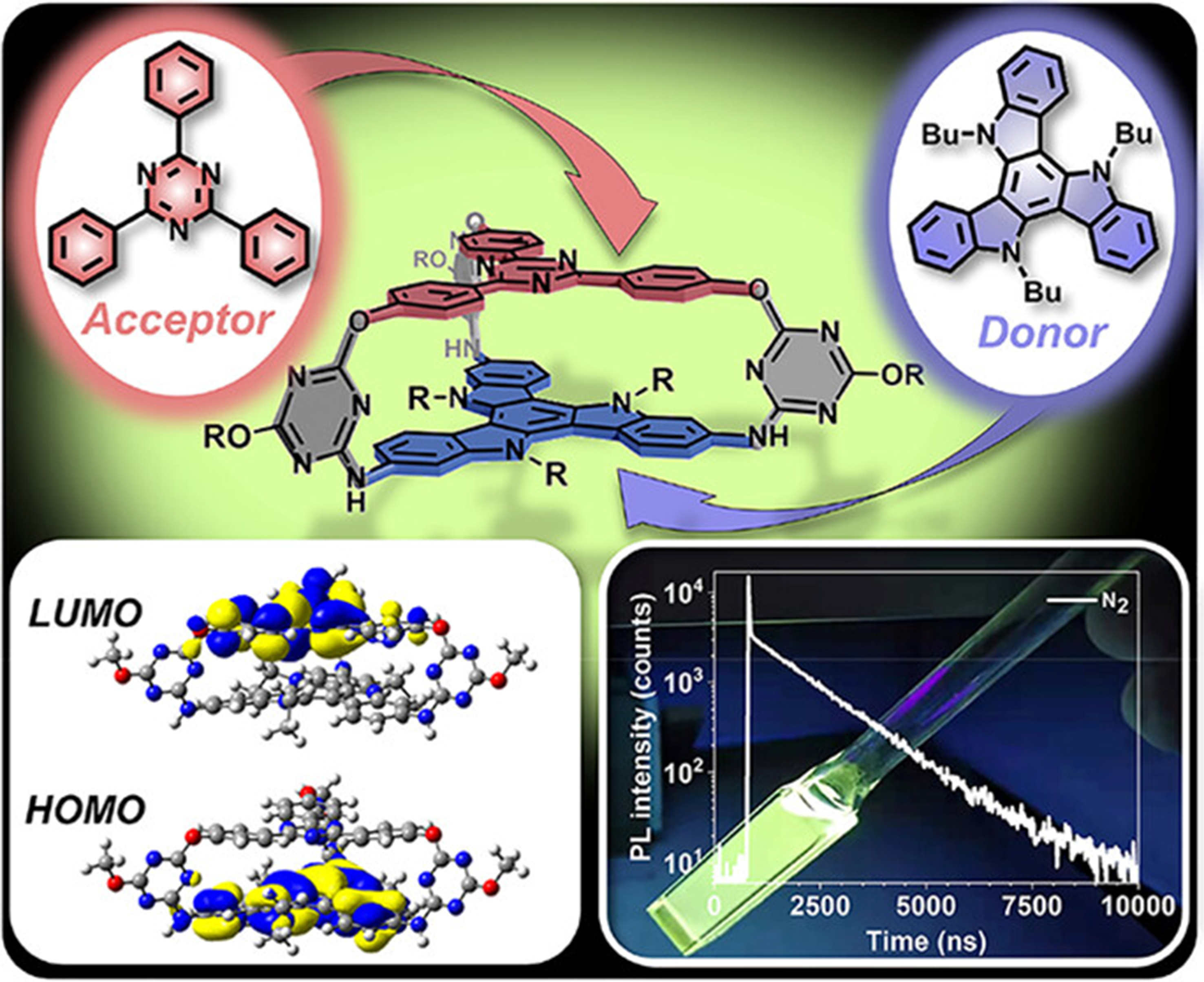

Different types of triazine precursors have been reported to construct organic cages, such as 2,4,6-trichloro-1,3,5-triazine[80], 4,4’,4”-(1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triyl)triphenol[17], 4,4’,4”-(1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triyl)tribenzaldehyde[81] [Figure 9A]. Lin et al. constructed an ether-linked cage from 4, 4’, 4”-(1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triyl)triphenol and 1,4-bis(bromomethyl)benzene, which worked as an electron-accepting container (A)[17]. By binding with N-methyl-indolocarbazole-based electron-donating guests (D), TADF exhibited by the host-guest complex through charge transfer, which showed a photoluminescence quantum yield of 63%[17]. The D and A components could also be built into an individual organic cage. Chen et al. reported another ether-cage composed of 4, 4’, 4”-(1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triyl)triphenol as an electron acceptor and 2,7,12-triamino-5,10,15-tributyltriindole as an electron donor [Figure 9B]. This cage had a parallel arrangement of the D and A component separated by suitable distance, which induced an intramolecular charge transfer and gave rise to a TADF with a photoluminescence quantum yield of 35% in degassed toluene solution[12].

Figure 9. (A) Triazine-derived precursors; (B) Synthesis route of a D-A organic cage[12]. Reproduced with permission, Copyright 2023, ACS.

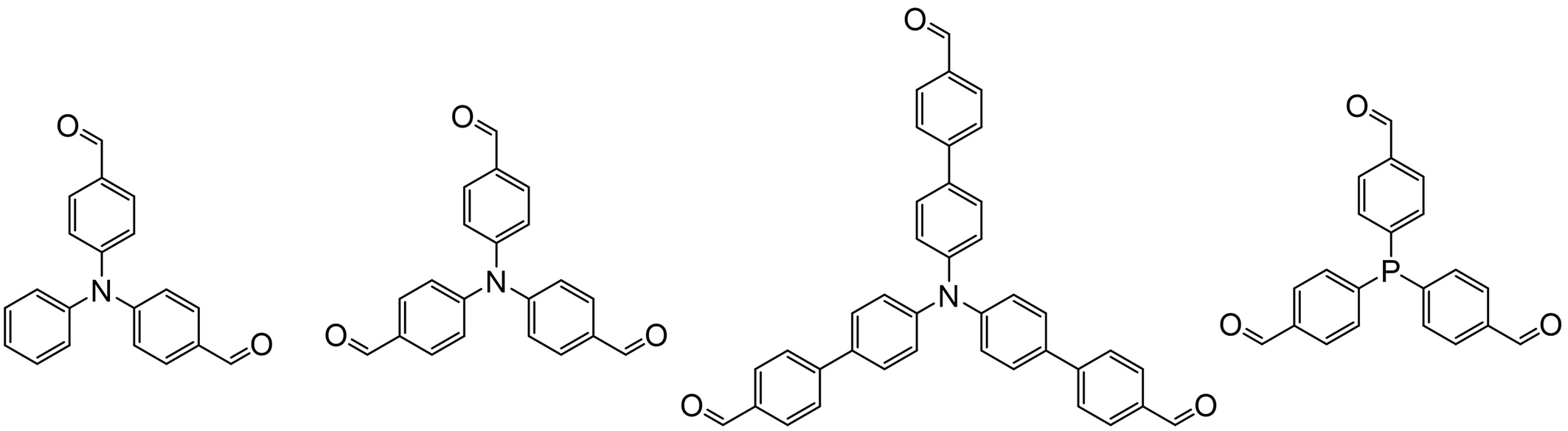

Fluorescent organic cages based on triphenylamine or triphenylphosphine derivatives

Triphenylamine and triphenylphosphine usually serve as electron donors in the D-π-A systems which could efficiently exhibit TADF. They could be used together with the above-mentioned centripetal triazine derivatives to construct fluorophore[82]. The lone electron pair on the N atoms would delocalize freely upon excitation and enhance energy transfer, and triphenylamine and triphenylphosphine also display AIE characteristics[83]. Besides, the star-shaped monomers with conjugated phenyl groups also work effectively for construction of rigid structures. Thus, both triphenylamine and triphenylphosphine could be employed in synthesis of fluorescent organic cages; Figure 10 lists some precursor examples. For example, an imine-linked cage F-COC synthesized form bis(4-formylphenyl)aniline and tris-(2-aminoethyl)amine displayed enhanced fluorescence emission in solvents with higher dielectric constants[84]. The F-COC was doped in a polystyrene polymer and fabricated into a film for detection of chloroform vapour, which presented much stronger fluorescence after sensing chloroform. Another example is that a phosphine-imine cage was constructed from 4,4’,4”-triformyltriphenylphosphine and cyclohexanediamine, which presented fluorescence with a quantum yield of 4.59% in a 2 mM dichloromethane solution. Besides the phosphine-imine cage displayed AIE phenomenon with a remarkably high photoluminescence quantum yield of 97.6% in its crystalline solid state.

Fluorescent organic cages based on other fluorescent groups

Other fluorescent groups besides above-mentioned examples were also successfully constructed into organic cage which gave fluorescence. For example, 5,5’-((2,5-dimethoxy-1,4-phenylene)bis(ethyne-2,1-diyl))diisophthalaldehyde, which is a conjugated precursor of phenyls linked by alkyne bonds, formed a [3+6] cage with cyclohexane diamine[85]. The imine cage displayed strong fluorescence with a quantum yield of 73% in tetrahydrofuran. Another emissive cage consisted of conjugated diphenyl sulfone units connected by nitrogen atoms could be prepared by C-N coupling reactions, which showed narrowband delayed fluorescence[86]. 4,4’-(benzothiadiazole-4,7-diyl)dibenzaldehyde and tris-(2-aminoethyl)amine self-assembled into a [2+3] benzothiadiazole-based imine cage, whose fluorescence could be turned on after addition of cadmium ionS, with fluorescent emission enhanced by seven times compared the pure cage solution[87].

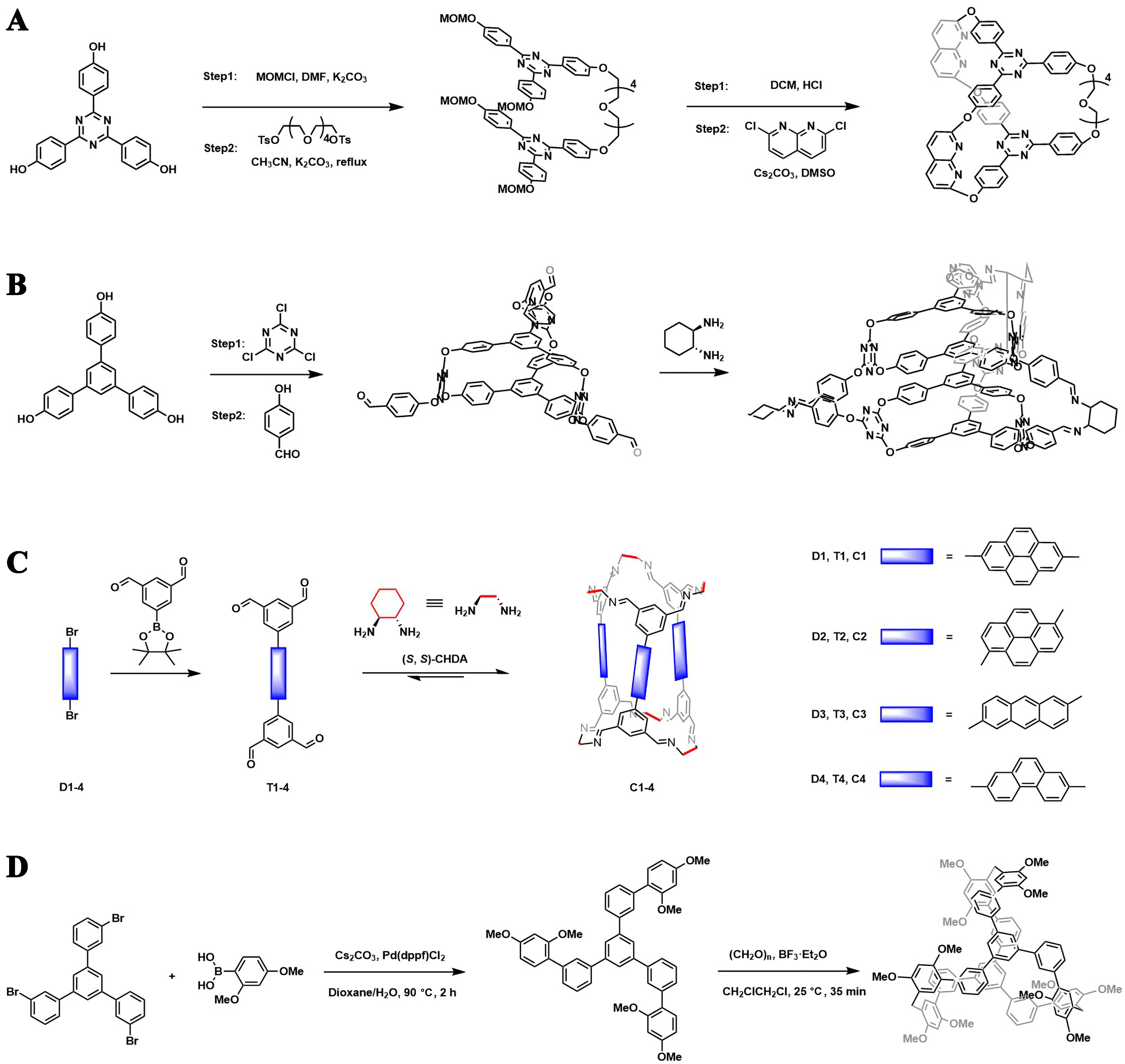

Apart from the predominant one-pot self-assembly, multistep-synthesis also plays a key role in the construction of fluorescent organic cages, which is more frequently observed when irreversible linking chemistry is involved, or an asymmetric cage is targeted. For example, Zhang et al. prepared a fluorescent organic cage through a two-stage stepwise method, where two 2,4,6-triphenyl-1,3,5-triazine were initially bridged by one pentavinyl oxide, and further by two 1,8-naphthyridines linkers through the Williamson reaction [Figure 11A][88]. The multi-step procedure merged different functional groups into one cage entity in a much-controlled manner and successfully afforded asymmetric organic cages. It is worth noting that multistep-synthesis works as an effective means to arrange chiral fluorescent units in a way that promises chiral polarized luminescence (CPL). For example, Wang et al. synthesized a racemic 3D trilobal propeller helical cage from the 2D trilobal propeller triphenylene. The 3D cage further acted as a building block to assemble into a higher-level chiral helical molecular cage. In the solid state, the helical cloverleaf-like cages packed into supramolecular structures of L-helix or D-helix nanofibers, realizing chiral features in different dimensions including atomic, microscopic and mesoscopic-level of chirality [Figure 11B][89]. CPL could also be achieved in less complex systems, where chiral fluorescent units are requisite and be introduced through one-pot imine condensation [Figure 11C][67], irreversible reaction [Figure 11D], etc.[90]. Construction of fluorescent organic cages with CPL signals enriches the fluorescent response formats, facilitating notable advantages in diverse applications, particularly in sensing technology.

Furthermore, the computationally driven design of fluorescent organic cages is an emerging and promising strategy[7], where the prediction of cage structures and properties is the main focus[91]. The high-throughput computational screening narrows down the candidate compounds, and significantly reduces the time needed to develop new materials[91-94], which will benefit the design of fluorescent cages with target performance. For example, through molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, the cage topologies could be predicted efficiently when the precursors are picked[95-99]. Berardo et al. screened 10,000 combinations of tritopic aldehydes and ditopic amines with the stk toolkit, and checked their shape persistence using MD[100]. They successfully screened a C2v triple aldehyde building block and received an asymmetric organic cage with high solubility through the reaction of the aldehyde with (1R,2R)-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine.

Apart from the cage topology, their molecular packing (either crystalline[101,102] or amorphous[103-106]), structural characteristics[107] and the resulting properties[108-110] could also be simulated computationally. For example, energy structure function (ESF) maps, which incorporated crystal structure predictions and physical property calculations, proved to be a new approach to discovering functional organic cages[111]. Slater et al. successfully utilized ESF maps to envisage a cage with a narrowed window size and tuned gas sorption performance[102]. The corresponding experimental gas adsorption properties of the cage systems were in good agreement with predicted values by ESF maps. For fluorescent cages, understanding the interplay between fluorescent groups and relevant packing, and resulting fluorescent emissions could be streamlined through computational approaches. Besides, combining computational modeling with robotic automation and high-throughput characterization techniques would afford a platform to screen suitable fluorescent cages with high efficiency.

APPLICATIONS OF FLUORESCENT ORGANIC CAGES

Fluorescent organic cages merge the high designability and tunability of fluorescent small molecule probes with the multifunctionality and porosity of organic cages, endowing them with characteristics of both organic cages and fluorescent small molecules. These include permanent porosity, good solubility, and stimuli-responsive activity. Such features have led to their extensive study in applications such as host-guest recognition and fluorescent imaging[7,14,17,112,113]. Moreover, compared to fluorescent framework counterparties, their enhanced solubility affords better solution processability, facilitating their fabrication into films and other forms through various techniques, thus holding potential for development into luminescent devices[114]. Finally, unlike amorphous polymers, cages with well-characterized strucutures can facilitate the pursuit of understanding of the structure-activity relationships[35]. Therefore, this chapter focuses on the applications of fluorescent organic cages.

Sensing

Since fluorescent organic cages can selectively capture target molecules with fluorescent signals as output, they have been widely used in areas such as environmental monitoring[71,115-120], explosive detection[25], and so on. By adjusting the building blocks and their substituents, fluorescent organic cages can be engineered to sense and analyze various ions[71], organic molecules[25], bioactive substances[17], and response to certain physical changes, such as pressure[35].

Ion sensing

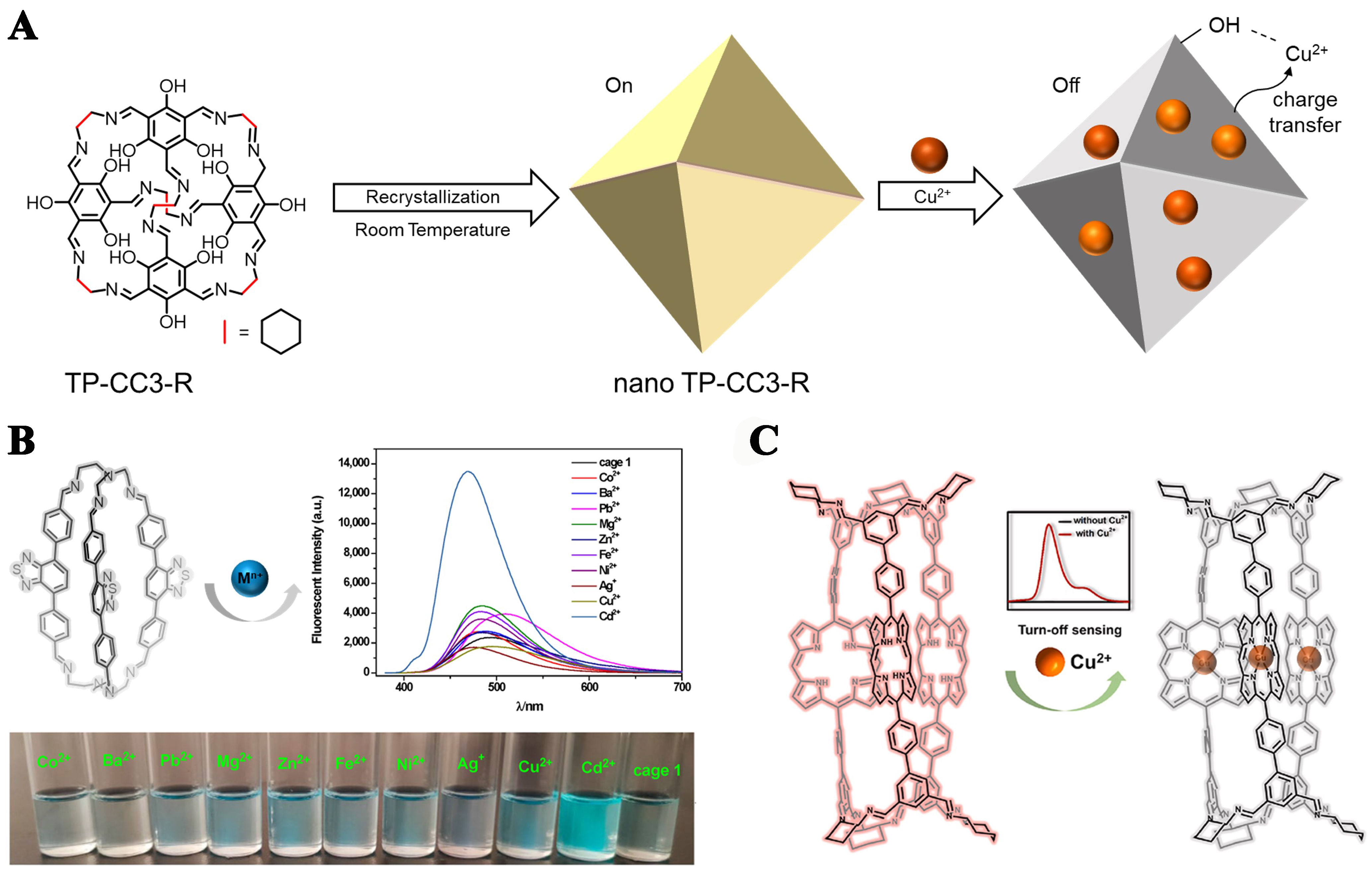

For metal ion detection, Dai et al. prepared ultra-small-sized nano TP-CC3-R by a facile room-temperature recrystallization method[71]. The prepared cages with stable emission at 535 nm could be used to detect Cu2+ sensitively and selectively by the combination of coordination interaction and charge transfer interaction between nano-TP-CC3-R and Cu2+ [Figure 12A]. The application of this fluorescence probe showed good selectivity, sensitivity, and accuracy in the determination of Cu2+ in real water samples. Wang et al. used benzothiazole-based [2+3] cages for Cd2+ detection [Figure 12B], which further extended the potential application of organic cages for heavy metal ion detection[87].

Figure 12. (A) The facile preparation of nano TP-CC3-R and the mechanism for fluorescence sensing of copper ion. Reproduced with permission[71], Copyright 2021, Elsevier B.V; (B) Benzothiazole-based [2+3] cages for Cd2+ detection. Reproduced[87], Open access, MDPI; (C) The porphyrin-based organic cage for Cu2+ sensing. Reproduced with permission[116], Copyright 2022, Elsevier B.V.

In addition, Ren et al. developed a porphyrin-based organic cage as a Cu2+ sensor [Figure 12C][116]. Owing to the stronger affinity of the cage towards Cu2+ than other metal ions, the probe exhibited excellent sensitivity and selectivity for Cu2+ and the limit of detection (LOD) of the cage for Cu2+ reached to 6.3 nM. Single crystal X-ray diffraction allowed the structure of the metal binding site to be clarified, which provided valuable structural information for the design of high-performance sensors.

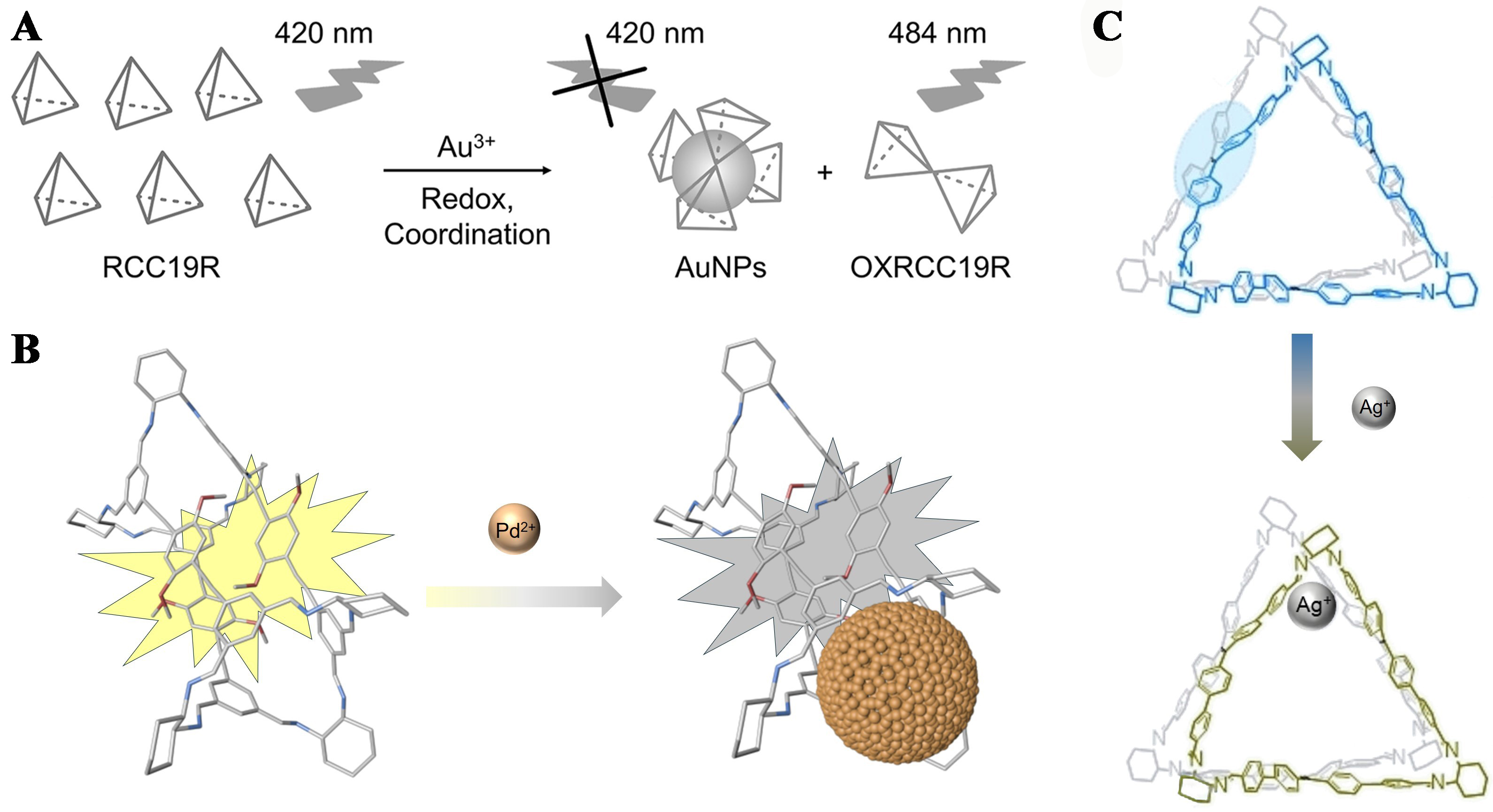

Furthermore, scientists have designed many organic cages for metal ion sensing, such as fluorescent RCC19 [Figure 13A] for ratiometric sensing of Au3+[72], (R)-1 [Figure 13B] featured in conjugated imine bonds and methoxyl oxygen atoms for the selective detection of Pd2+[85], and TPE-based fluorescent organic cages

Figure 13. (A) RCC19 for the highly sensitive and selective detection of Au3+. Reproduced with permission[72], Copyright 2022, Elsevier B.V.; (B) (R)-1 for the selective detection of Pd2+. Reproduced with permission[85], Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH; and (C) the TPE-based fluorescent organic cage for the detection and recycling of Ag+. Reproduced with permission, Copyright 2023[115], Wiley-VCH. TPE: Tetraphenylethylene.

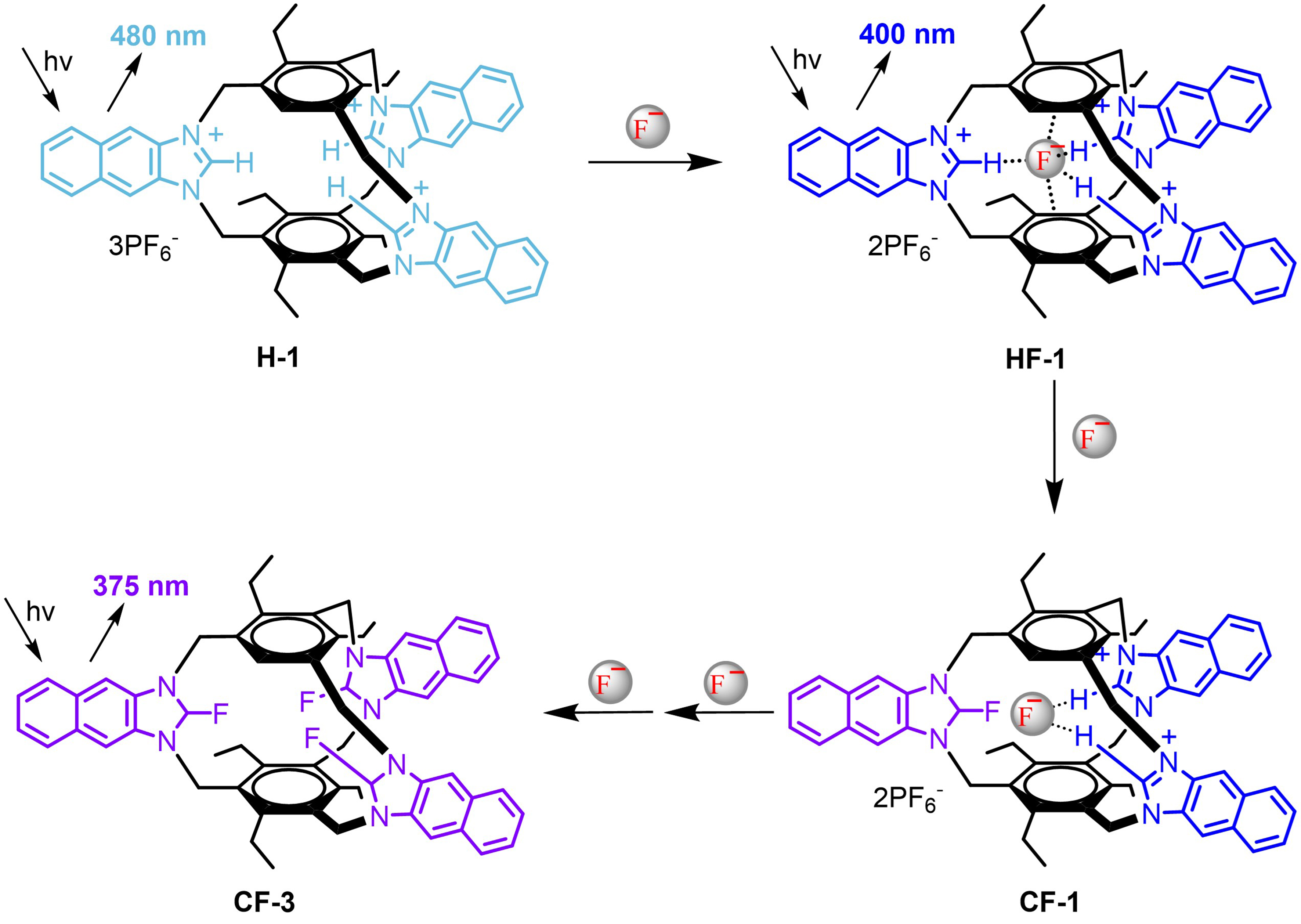

In the area of anion sensing, Pan et al. devised an organic molecule cage denoted as H-1, comprised of three imidazolium cations and two benzene rings in the structure[119]. The interaction between the organic molecule cage H-1 and fluoride ions was accompanied by a continuous fluorescent color alteration [Figure 14]. The recognition of a specific structure through ingenious and precise molecular design provided a multi-channel fluorescence signal output method for the quantitative detection of fluoride ions.

Figure 14. The interaction between compound H-1 and fluoride ions. Compounds HF-1, CF-1, and CF-3 were formed based on the anion-π interaction and the formation of C-F covalent bonds, while showing a continuous fluorescent color alteration. Reproduced with permission[119], Copyright 2023, Elsevier B.V.

In addition, Bian et al. designed TPE-based cages that could recognize I3-[118]. Zhao et al. employed a hexapyrrolic tripodal precursor to prepare the ester-imide cage, demonstrating stability in organic solutions and a strong affinity for anions in chloroform[117]. These discoveries facilitated the development of stable anion sensors within organic solvents, which is particularly important for the detection of trace anions in solvents.

Explosive sensing

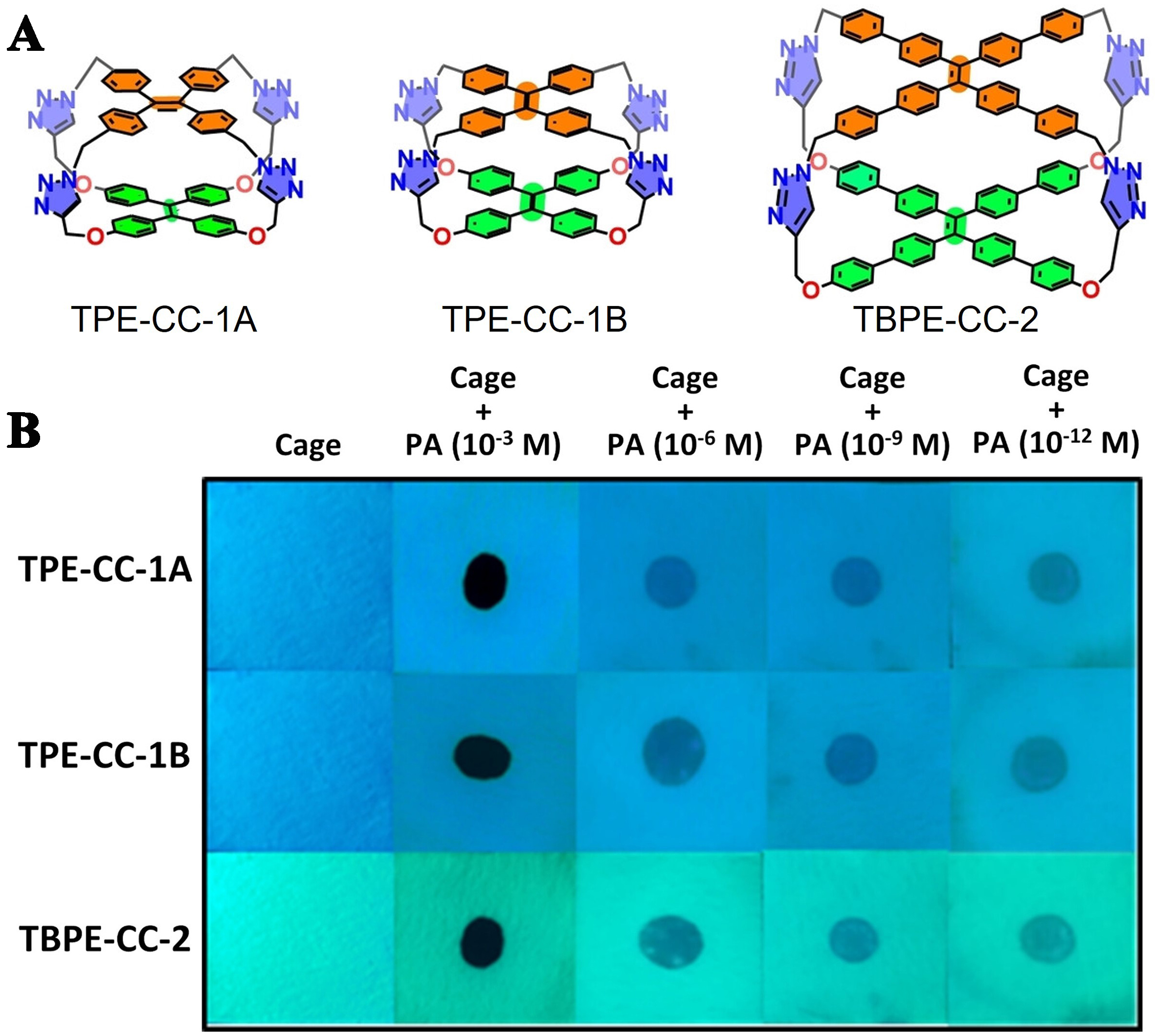

The sensing of explosives by fluorescent organic cages is primarily achieved through energy transfer and charge transfer between the fluorescent organic cages and the explosives. For example, Acharyya et al. developed fluorescent organic cages based on triphenylamine, which were capable of detecting picric acids (PAs) via charge transfer and resonance energy transfer mechanisms[13,121]. The cage showed high sensitivity and selectivity for other nitroaromatic explosives, with potential applications for distinguishing highly explosive substances from non-target compounds. Sharma et al. and Tao et al. constructed diverse fluorescent cages by imine condensation reaction, respectively[122,123]. These cages showed great sensitivity and selectivity in recognizing nitroaromatic explosives.

Additionally, Maji et al. engineered three cages based on TPE and TBPE, showcasing exceptional AIE properties and solid-state emissions via four-fold Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) “click” reactions[25]. These organic cages could selectively detect PAs in water through a photoinduced electron transfer mechanism, providing a very effective and convenient tool, paper strips, for water monitoring [Figure 15]. These breakthrough studies not only provided an accurate method for explosives tracking but also demonstrated the great potential of organic cages in environmental monitoring and for public safety.

Figure 15. (A) The structure of TPE cages; (B) Photographs of fluorescence quenching of paper strips coated with cage molecules

Biomarkers sensing

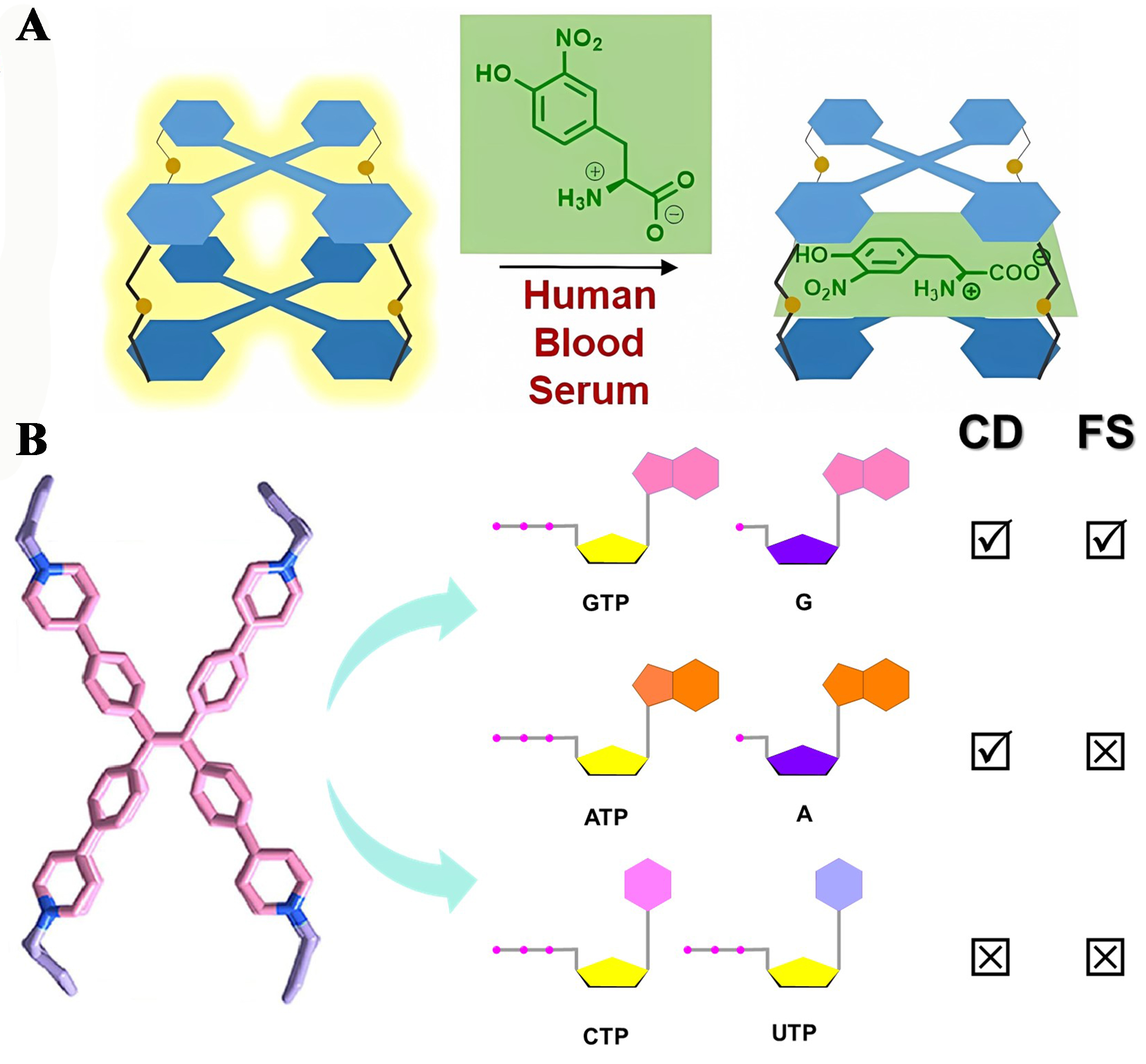

Montà-González et al. developed a TPE-based fluorescent cage and used it as the first sensor for high-affinity capture of 3-nitrotyrosine (NT) in water [Figure 16A][27]. This fluorescent cage showed a new potential application in the early diagnosis of chronic kidney disease due to its linear fluorescence bursting of NT in human serum.

Figure 16. Fluorescent organic cages for biomarkers sensing. (A) The TPE molecular cage sensor of NT that works in human blood serum. Reproduced[16], Open access, Wiley-VCH; (B) The TPE-based cage functioned as both a biomolecular chiral sensor and a fluorescent probe. Reproduced with permission, Copyright 2024[49], Elsevier B.V. TPE: Tetraphenylethylene; NT: 3-nitrotyrosine.

Duan et al. synthesized a TPE-based cage featuring dual “claw-like” cavities, capable of sequestering two nucleotide molecules in a 1:2 ratio[49]. This cage utilizes the inherent fluorescent nature of the TPE moiety and its chiral spinning conformation to function as both a biomolecular chiral sensor and a fluorescent probe. The structure demonstrated a multifaceted orthogonal response, simultaneously exhibiting changes in fluorescence and circular dichroism (CD) upon interaction with various nucleotide molecules in aqueous environments [Figure 16B]. Similarly, Cao et al. crafted hexacationic cages incorporating TPE motifs that possessed open cavities[48]. These structures have been adeptly employed as chiral and fluorescent sensors to differentiate between the reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and the oxidized form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+).

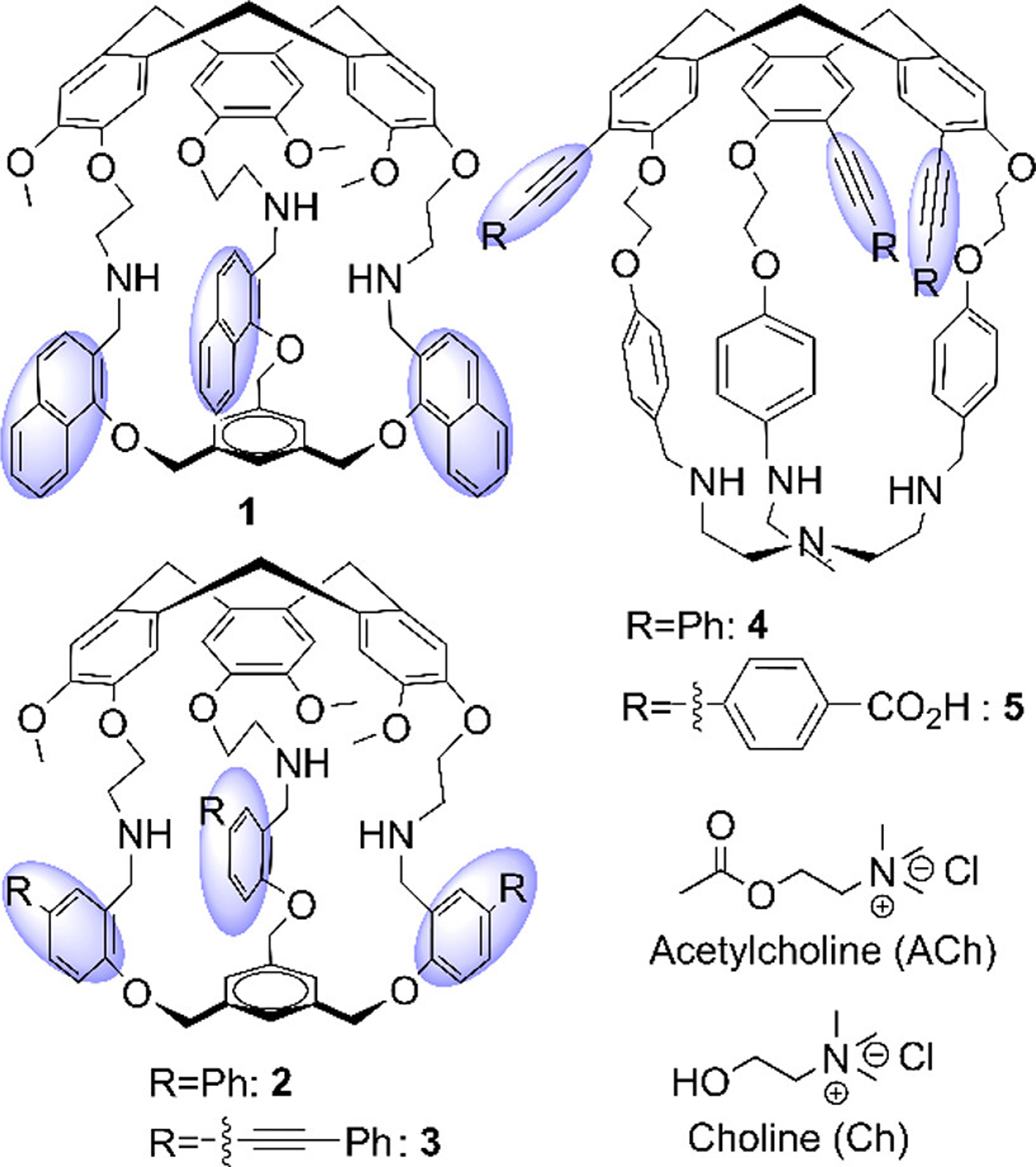

Furthermore, scientists synthesized a series of fluorescent cages (1-5, Figure 17) by incorporating various fluorophores or fluorescent entities into cyclotriveratrylene (CTV) macrocycles[124]. Among these, Cages 1, 2, and 3 can selectively recognize acetylcholine (ACh) and choline (Ch) (KAch/Kch = 4.1, 2.8, and 4.4, respectively), whereas Cage 5 can selectively recognize Ch in a pseudo-physiological medium. However, Cage 4 is unable to differentiate between ACh and Ch. Such fluorescent organic cages, endowed with the capacity for single or multiple responses, significantly enhanced the discernment and detection of biomolecules with closely related chemical structures in aqueous, biologically relevant environments.

Figure 17. Fluorescent hemicryptophanes and targeted guests. Reproduced with permission, Copyright 2023[124], ACS.

Other applications in sensing

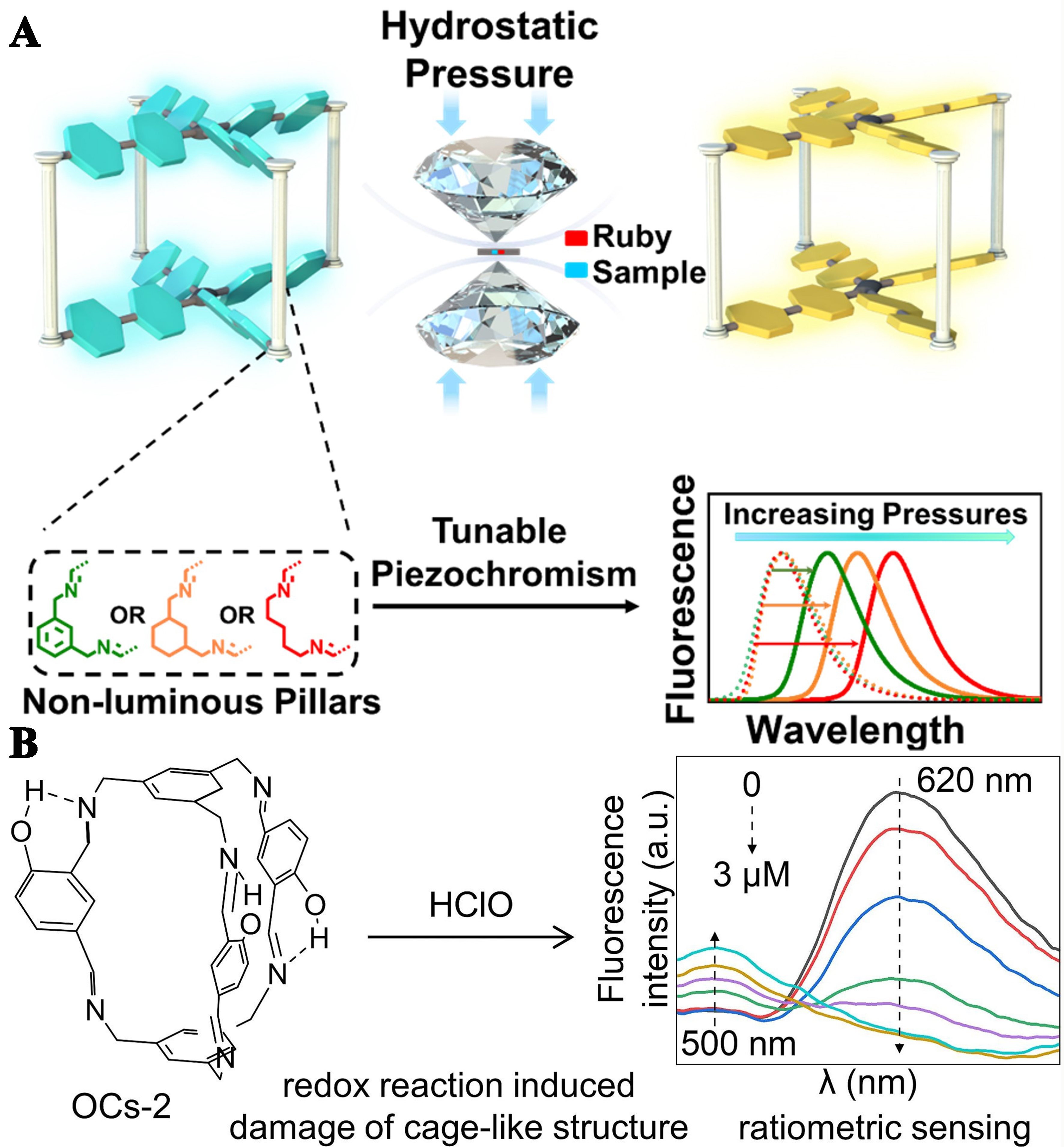

In addition to ions, explosives, and bioactive substances, fluorescent organic cages can also respond to other physical or chemical stimulation. For instance, Li et al. used the DCC method to design and synthesize a series of flexible and tunable fluorescent organic cages based on TPE-cored AIE fluorophores[35]. The enclosed cage structure not only provides ample space for conformational changes of the fluorophores but also protects against deformation due to its structural elasticity. Subsequently, using diamond anvil cell (DAC) technology, they studied its pressure-induced fluorescence color change properties under pressure stimulation and achieved control over the pressure-induced fluorescence color change behavior of the organic cages [Figure 18A]. Dai et al. developed OCs-2 for HClO ratio sensing[70]. Due to enol-keto tautomerism and restricted molecular motion within its cage-like topology, OCs-2 exhibits pH-responsive dual emission characteristics associated with hydroxy-1,3-diaminobenzene related excited-state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) and AIE fluorescence. The redox reaction between HClO and the imine bond results in the destruction of the OCs-2 cage structure, producing a proportional fluorescence signal [Figure 18B]. OCs-2 demonstrates excellent performance in detecting HClO in domestic water and disinfectant samples, with recoveries ranging from 94.09% to 104.24%.

In the field of anti-counterfeiting, Song et al. fabricated a fluorescent organic cage that displayed different photoluminescence colors and intensities in various media and exhibited AIE effects in the absence of dissolved solvent[125]. These captivating nanocages could act as anti-counterfeiting inks, allowing for the recording and erasing of data information via air drying and steam fumigation, respectively. Zou et al. synthesized the cage FT-RC, which possessed photochromic and luminescent properties, holding substantial potential for applications in anti-counterfeiting[33].

Optoelectronic materials

Fluorescent organic cages, with their outstanding luminescent properties, high stability, and superior quantum efficiency, are garnering notable attention in the field of optoelectronic materials[12,17,126]. The molecular cavities inherent in fluorescent organic cages enable them to act as host molecules that can load and immobilize luminescent guests, thereby regulating their photophysical properties[126]. As the exploration of fluorescent organic cages and their host-guest interactions deepens, their advantages as promising luminous materials are gradually coming to light.

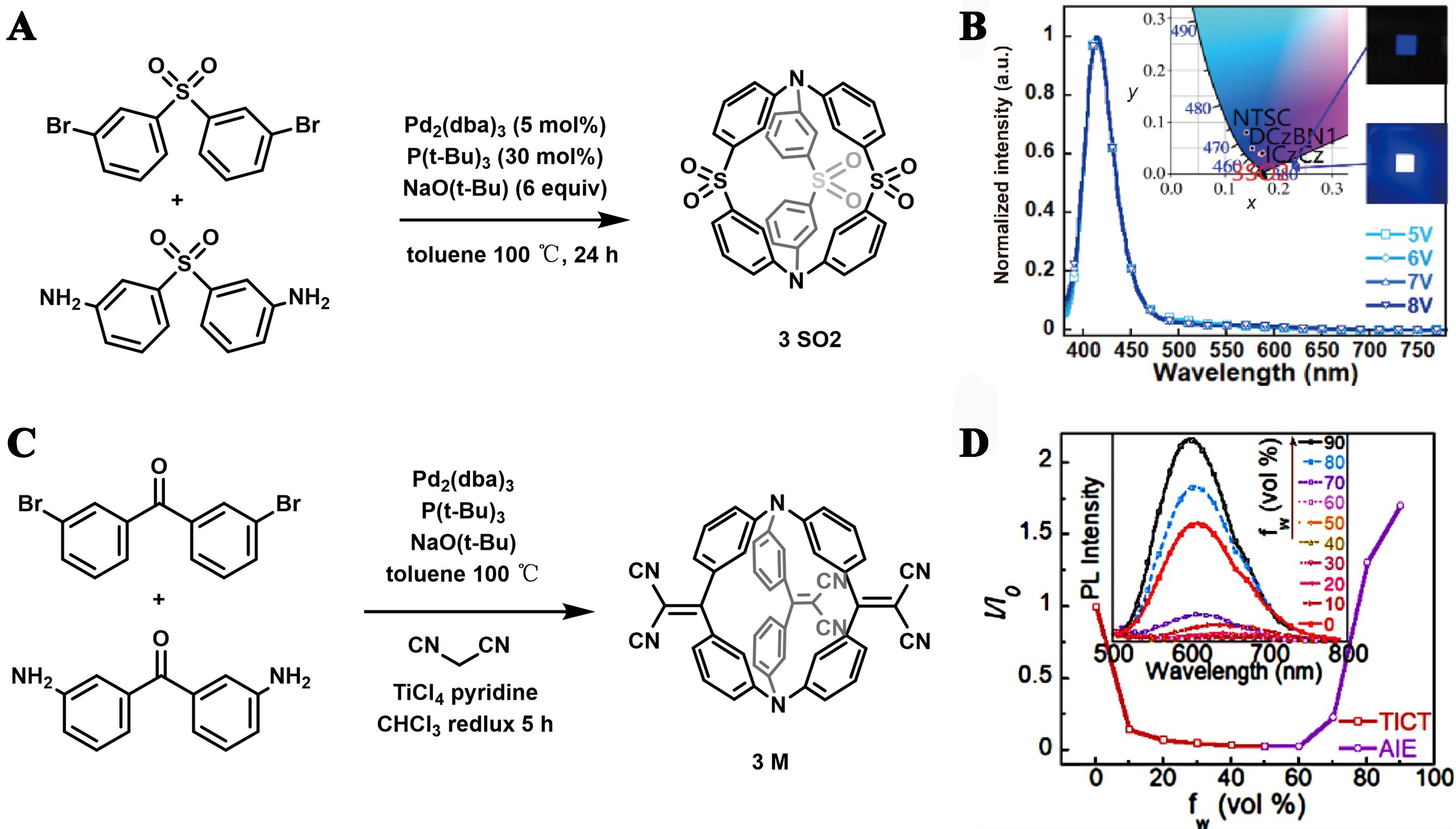

Hu et al. constructed an organic cage structure termed as 3SO2 [Figure 19A], which comprised of diphenyl sulfone units and nitrogen atoms[86]. This cage structure exhibited not only excellent narrowband emission, but also deep blue TADF [Figure 19B], opening new avenues for the development of optoelectronic devices requiring specific emission wavelengths. Furthermore, another small molecular organic cage, 3M, developed by the same team, stood out for its superb solubility and structural stability [Figure 19C and D]. It demonstrated red TADF properties in its aggregated state. This work may significantly broaden the research into fluorescent organic cages, particularly those with high solubility and AIE characteristics exhibiting TADF[114].

Figure 19. (A) Synthetic routes of 3SO2; (B) EL spectra of the device based on 3SO2 under different voltages. Inset: EL color coordinates on the CIE 1931 chromaticity diagram and EL emissions from the 3SO2-based device in low luminance (up) and high luminance (down). Reproduced with permission[86], Copyright 2020, Springer Nature; (C) Synthetic routes of 3 M; (D) Plot of I (emission intensity)/I0 (emission intensity in THF solution) of 3M vs. water fractions of the solvent mixture. Inset: PL spectra of 3M (10-5 mol/L) in THF/water mixtures with different water fractions. Reproduced with permission[114], Copyright 2020, Elsevier B.V. EL: electroluminescence; CIE: commision internationale de l’eclairage; THF: tetrahydrofuran; PL: photoluminescence.

Additionally, Chen et al. successfully integrated electron-donating and electron-accepting components within the same organic cage[12]. This meticulously engineered D-A structure facilitated effective intramolecular through-space charge transfer, exhibiting a negligible singlet-triplet energy difference and associated TADF [Figure 20]. Enormous potential for application in high-performance luminous devices was highlighted due to the TADF properties demonstrated in both solution and solid states of the organic cage, along with its impressive photoluminescence quantum yields.

Figure 20. The D-A organic cage for TADF. Reproduced with permission[12], Copyright 2023, ACS. TADF: Thermally activated delayed fluorescence.

Recently, Lin et al. synthesized an organic Trz-cage which worked as an electron acceptor, and investigated its host-guest complexation with a series of electron donors[17]. Experiments using TrMe as the electron donor indicated that complexation in solution was an entropy-driven process. A sufficiently short D-A distance with face-to-face orientation resulted in effective spatial charge transfer and TADF properties, achieving high emission efficiency in organic light-emitting diode (OLED) devices.

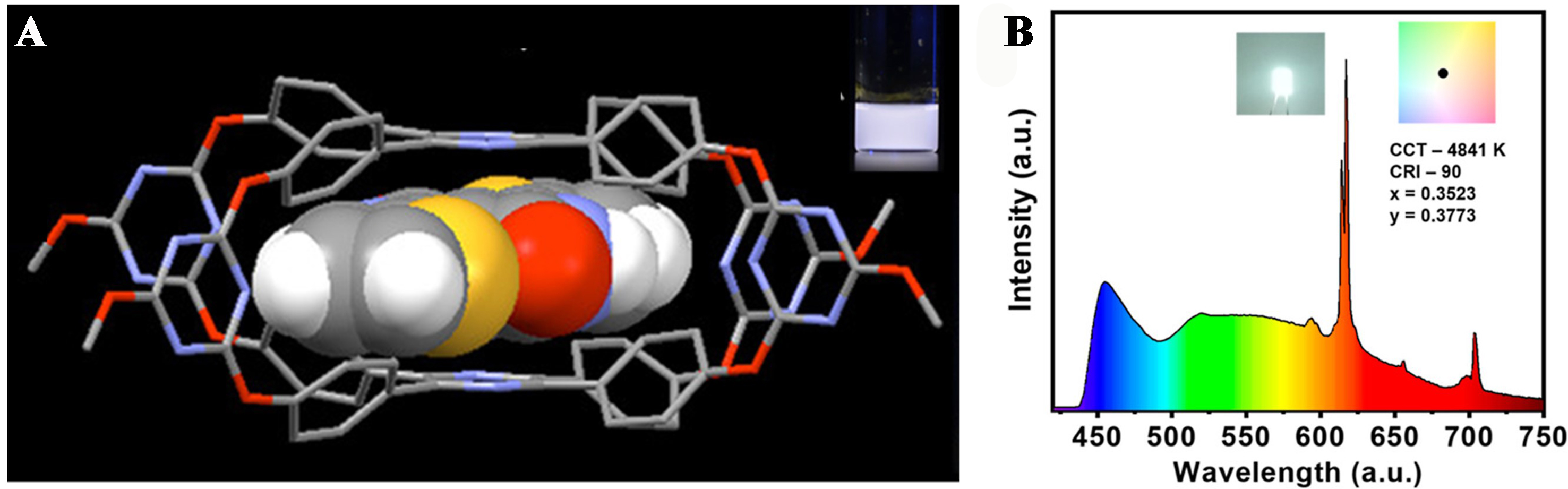

Furthermore, Feng et al. designed and synthesized an amphiphilic tetraphenylpyrazine (TPP)-cage[126]. When complementary colored guest molecules, diketopyrrolopyrrole, were introduced to the TPP-cage, the resulting host-guest complexes exhibited stable white light emission in both aggregated states and poly(ethylene glycol) film [Figure 21A]. Most recently, Mahto et al. reported the formation of J-aggregates in crystalline structures through Van der Waals interactions using the cage molecule COC1[127]. By coating a layer of polymer doped with red phosphor on the surface of a blue LED and applying a COC1 film, they created a cold white light LED [Figure 21B]. Electroluminescent studies indicate that the COC1 cage material can be utilized for the development of white LEDs. These advancements offer new strategies for the design and construction of luminescent materials.

Figure 21. (A) White-light emission from supramolecular assembly. Reproduced with permission[126], Copyright 2018, ACS; (B) Electroluminescence spectrum of the fabricated WLED. Coated COC1 cage material along with red emissive phosphor over the blue LED bulb. Inset pictures show the emission color of the fabricated white LED. Reproduced with permission[127], Copyright 2024, ACS. WLED: White light-emitting diode; LED: light-emitting diode.

Bio-related applications

The cavity of fluorescent organic cages can be loaded with biologically active substances or drugs, showcasing their potentials in drug delivery[15,47]. In addition, fluorescent organic cages with hydrophilic surfaces and stimulus-responsive properties can broaden the application of organic cages in bioimaging and other biologically related fields[14].

Imaging

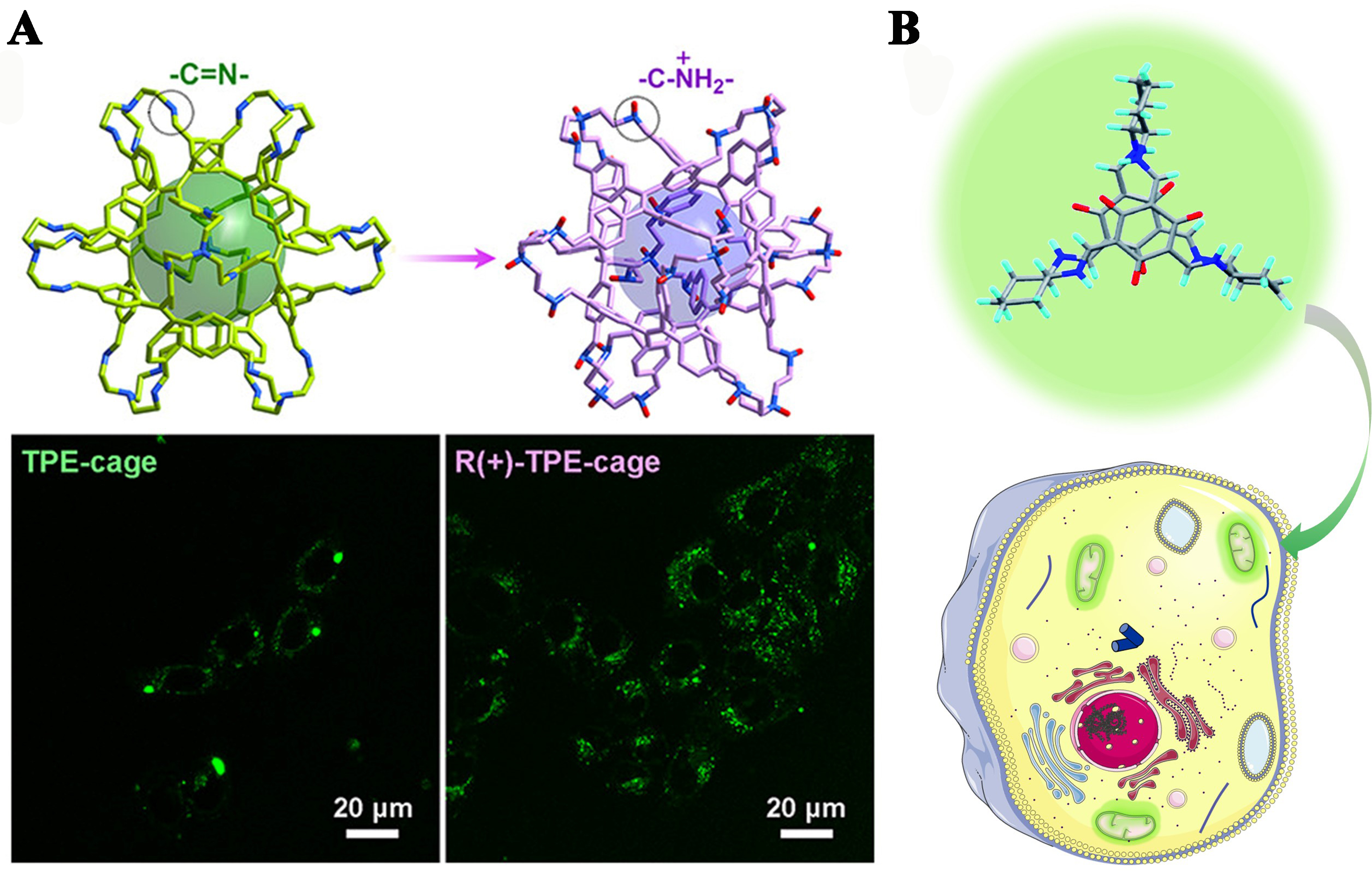

Hydrophilic organic cages with high fluorescence emission and photostability demonstrate promising applications in bioimaging. For example, Dong et al. enhanced the application of fluorescence organic cages by chemically transforming the rigid imine bonds into relatively flexible amine bonds, thereby enabling the TPE components to exhibit AIE characteristics[14]. Subsequently, they created a positively charged R(+)-TPE cage through protonation, which significantly improved its hydrophilicity and augmented the AIE features. The results indicated that the R(+)-TPE cage had a highly sensitive response to temperature and viscosity changes, providing a valuable tool for live-cell bioimaging [Figure 22A]. Al Kelabi et al. crafted an organic cage (OC1), a fluorescent switchable isomeric organic cage with exceptional biocompatibility, using imine condensation reactions[69]. This cage was designed to be a fluorescent probe that can selectively target mitochondria [Figure 22B], offering a means for targeted imaging within living cells.

Figure 22. (A) AIE-active organic cages and their applications in biological imaging. Reproduced with permission[14], Copyright 2022, ACS; (B) The biocompatible OC1 was employed as a mitochondria-targeted fluorescent probe. Reproduced[69], Open access, Copyright 2022, RSC. AIE: Aggregation-induced emission.

Zheng et al. developed a TPE-based organic cage that exhibited exceptional fluorescence emission in dilute solutions and maintained stability in the solid state by dynamic imine chemistry[34]. The distinctive feature of this organic cage confers the potential to serve as a reliable platform for live cell monitoring. Recently, Chen et al. showed a molecular cage containing two porphyrin sensitizers, which, upon forming a supramolecular complex with two annihilators (perylenes), led to triplet-triplet annihilation-based photon upconversion under low-energy light excitation[57]. This property enabled the successful utilization of the molecular cage in the imaging of cancer cells.

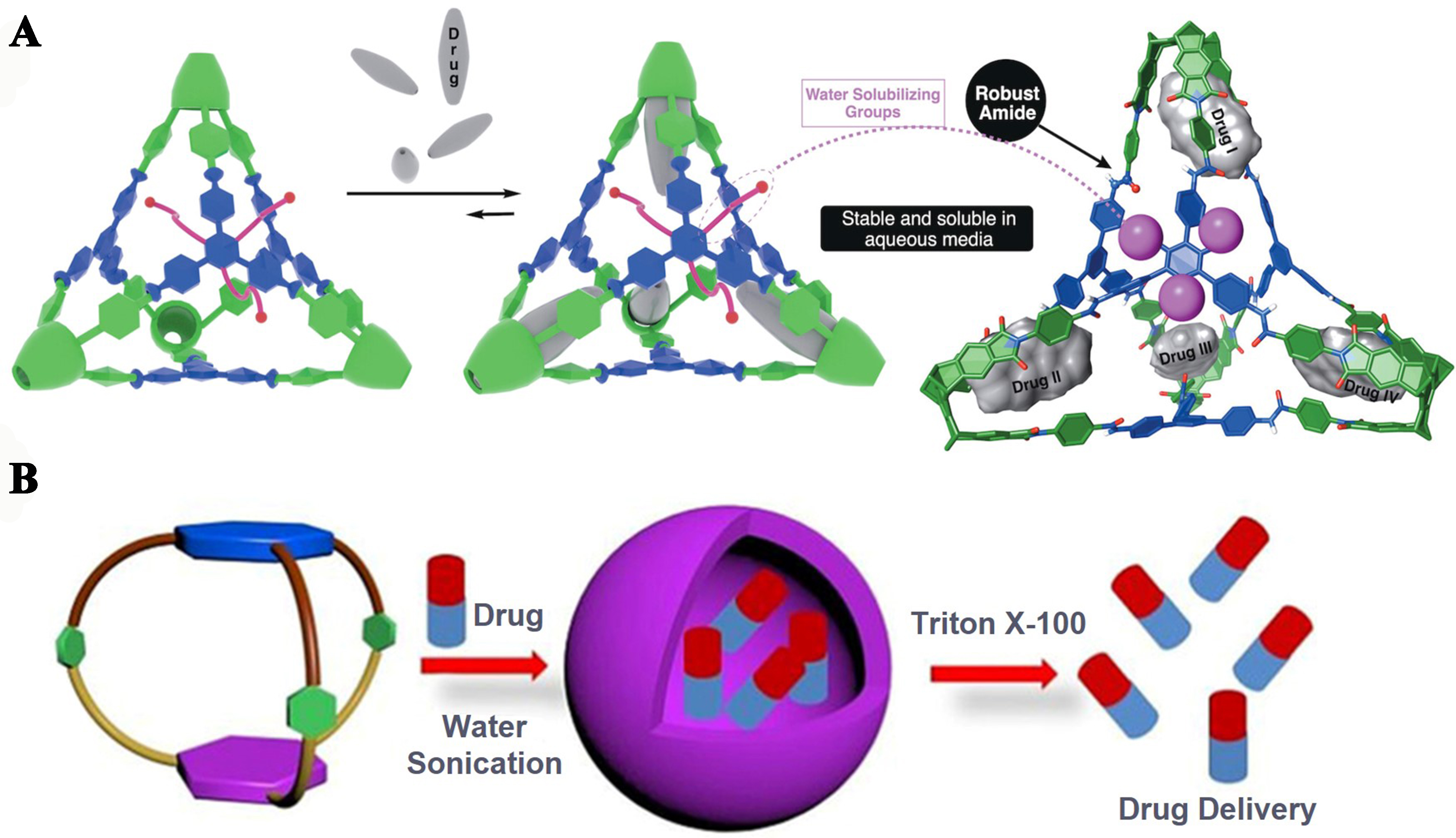

Drug delivery

The cavities within organic cages offer a significant advantage for the encapsulation and transport of drugs. Liyana Gunawardana et al. ingeniously designed biocompatible large covalent basket cages (CBCs) featuring robust, rigid amide bonds and charged functional groups on their exterior surfaces[15]. These CBCs, which had good solubility in water at physiological pH and the ability to form crystalline nanoparticles, could effectively encapsulate anticancer drugs [Figure 23A]. They highlighted the potential of CBCs as multivalent agents for the delivery of pharmaceuticals.

Figure 23. (A) CBCs installed charged groups at the outer surface to improve the stability and solubility in aqueous media, which could effectively encapsulate anticancer drugs. Reproduced[15], Open access, Wiley-VCH; (B) Self-assembly of organic cages in water for encapsulation of DOX and its release. Reproduced with permission[128], Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH. CBCs: Covalent basket cages; DOX: doxorubicin hydrochloride.

Duan et al. introduced a TPE-based octacationic supramolecular drug delivery system, which was engaged in host-guest complexation with drugs (e.g., camptothecin, CPT) in water[47]. This water-soluble cage functioned as a solubilizer, enhancing the aqueous solubility and consequently the bioavailability of water-insoluble drugs. Its fluorescent properties also enabled successful monitoring of the drug release during cancer therapy in living cells. Sarkar et al. synthesized organic cages with extensive π surfaces and pioneered the formation of cage-based vesicles for loading the anticancer drug doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX)[128]. Upon exposure to the vesicle destroyer Triton X-100, these unique structures could release DOX into cancer cells [Figure 23B], charting a promising route for the development of spherical vesicles derived from organic molecules for drug delivery applications.

Other biomedical applications

In constructing fluorescent organic cages, the direct incorporation of building blocks with specific biological functions, or the post-modification of fluorescent organic cages, can further functionalize them for various biologically related applications.

In the field of photodynamic therapy (PDT), the interesting work by Zhu et al. has showcased the promising application of organic cages based on porphyrin structures, which enhanced the generation of both Type I and Type II reactive oxygen species (ROS) [Figure 24][51]. It was the characteristics of the Py-Cage, especially its resistance to ACQ in high-concentration aqueous solutions, along with its large cavities and high porosity, that significantly boosted the efficiency of ROS production. Furthermore, Py-Cage, with its improved charge separation and transfer capabilities, serves as an exemplary model for the design and synthesis of biocompatible porous photosensitizers, opening new avenues for PDT-related clinical treatment strategies.

Figure 24. (A) Schematic of the synthesis of the Py-Cage; (B) schematic of the working mechanism of the Py-Cage for PDT applications. Reproduced with permission[51], Copyright 2023, RSC Pub. PDT: Photodynamic therapy.

In the realm of antibacterial research, Dong et al. explored the dual-responsive nature of a water-soluble TPE-based octacationic cage in the identification and detection of β-lactam antibiotics[129]. The fluorescent cage complexes formed with antibiotics exhibited remarkable antibacterial activity, providing novel strategies for developing single-molecule fluorescence sensing platforms for antibiotic detection and drug delivery systems. Most recently, Zhang et al. developed pyrgos[n]cages, whose rigid structure and uniformly distributed surface positive charges allow them to exhibit potent antibacterial properties and good biocompatibility[130]. Pyrgos[n]cages can disrupt bacterial membrane potential and target DNA, exhibiting significant bactericidal effects on both intracellular and extracellular bacteria, including drug-resistant strains. Particularly, they show great potential in combating intracellular and drug-resistant bacteria, providing a new approach for the development of new antimicrobial drugs [Figure 25].

Additionally, Benke et al. revealed new possibilities for single-molecule synthetic anion channels with organic cages based on porphyrins[131]. The carefully designed size and cavity structure of the cage allowed it to act as a single-molecule channel for transmembrane transport of anions, particularly exhibiting a high selectivity for I- [Figure 26]. These findings offered new insights into the mechanisms of cellular transmembrane transport while potentially influencing the treatment of iodide transport disorders.

Figure 26. Iodide-selective synthetic ion channels based on shape-persistent organic cages. Reproduced with permission[131], Copyright 2017, ACS.

Wang et al. utilized AIE-active TPE cages as initiators for atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) to obtain amphiphilic cage-containing polymers (CNP)[11]. Afterward, the authors encapsulated different dyes into the CNP, tuning the luminescence of obtained nanoparticles through a three-fluorescence cascade Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET). The nanoparticles not only established a trichromatic fluorescent system but also enabled temperature-responsive color changes triggered by environmental alterations [Figure 27A]. The development of such multifunctional materials held potential significance for biological imaging and temperature sensing and carried profound implications for the design of smart materials. Similarly, Zhao et al. synthesized TPE-cage-based temperature-sensitive polymers with blue, yellow, and red emission characteristics[50]. These polymers can be combined through the FRET effect to form stable white-light-emitting composite nanoparticles. The resulting nanoparticles exhibit excellent fluorescence stability and can be used for long-term cell imaging, providing a new tool for biomedical research [Figure 27B].

Figure 27. (A) Graphical representation of CNP assembly into hybrid nanoparticle and confocal microscope images of HeLa cells stained with white light-emitting hybrid nanoparticle at different temperatures. Reproduced with permission[11], Copyright 2020, ACS; (B) White light emissive TPE cage-based CNP for intracellular long-term imaging. Reproduced with permission[50], Copyright 2024, ACS. CNP: Cage-containing polymers; TPE: tetraphenylethylene.

Sun et al. achieved a derivative with an amplified fluorescence effect through chemical modification of the cage RCC1 [Figure 6A][6]. This modified cage, D-RCC1, exhibited very high quantum yields in both dilute organic solutions and the solid state. Moreover, the low toxicity and exceptional cell imaging properties of D-RCC1 provided new directions for the development and application of imaging agents.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

Fluorescent organic cages preserve the inherent cavity structure while effectively organizing light-emitting units within the cage structures after molecular packing. The combination of molecular cavities and fluorescence endows these cages with versatile applications including sensors, biocompatible probes, drug carriers with monitoring capabilities, luminous devices, and beyond. Despite their vast potential, fluorescent organic cages still face certain limitations and challenges, with many of their fluorescence characteristics remaining underutilized. Looking ahead, it is essential to address these hurdles and constraints to fully harness their capabilities.

(1) Despite the widespread application of organic cages in sensing, challenges such as environmental vulnerability persist. Most fluorescent organic cage sensors remain solution-based, limiting their practical utility. Therefore, simplifying the preparation and processing methods of these sensors and reducing interference from complex matrices are critical. Additionally, the development of portable devices, such as smartphones, integrated with fluorescent organic cages is crucial to enhance their usability.

(2) Although fluorescent organic cages may exhibit enhanced degradability and reduced biotoxicity compared to metal-organic cages (MOCs), MOFs, and COFs[9], they are still not ready for clinical applications. Therefore, it is critical to enhance their in vivo stability and biocompatibility. Additionally, it is essential to improve the accuracy and sensitivity of target molecule identification while minimizing potential adverse effects on biological systems.

(3) Research integrating fluorescent organic cages into light-emitting devices remains primarily in the laboratory phase. Future studies should focus on scaling up production and refining processing techniques to facilitate the development of practical, user-friendly, and efficient light-emitting devices.

(4) By leveraging computational techniques, we can predict novel organic cage structures with enhanced properties, enabling the screening of materials that exhibit superior biocompatibility and environmental sustainability. Computer-led discovery is poised to unlock significant opportunities for fluorescent organic cages in the development of commercial high-performance optoelectronic devices, and it also has the potential to advance applications in medical diagnostics and environmental monitoring.

As we continue to explore building units, synthesis methods, mechanisms of action, and applications of fluorescent organic cages, these materials are expected to offer extensive opportunities for both research and industrial applications. They hold promise in diverse fields such as medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and the development of innovative luminescent devices.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, writing - original draft, review and editing: Jia, Z.; Kai, A.

Supervision, writing - review and editing: Liu, M.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22371252), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Fund (LZ23B020005), and the Leading Innovation Team grant from the Department of Science and Technology of Zhejiang Province (2022R01005).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Duan, Y. C.; Wen, L. L.; Gao, Y.; et al. Fluorescence, phosphorescence, or delayed fluorescence? - A theoretical exploration on the reason why a series of similar organic molecules exhibit different luminescence types. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2018, 122, 23091-101.

2. Fang, M.; Yang, J.; Li, Z. Light emission of organic luminogens: generation, mechanism and application. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 125, 100914.

3. Ockwig, N. W.; Delgado-Friedrichs, O.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O. M. Reticular chemistry: occurrence and taxonomy of nets and grammar for the design of frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005, 38, 176-82.

5. Xue, R.; Guo, H.; Wang, T.; et al. Fluorescence properties and analytical applications of covalent organic frameworks. Anal. Methods. 2017, 9, 3737-50.

6. Sun, Y. L.; Wang, Z.; Ren, C.; et al. Highly emissive organic cage in single-molecule and aggregate states by anchoring multiple aggregation-caused quenching dyes. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 53567-74.

7. Yang, X.; Ullah, Z.; Stoddart, J. F.; Yavuz, C. T. Porous organic cages. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 4602-34.

8. Wang, H.; Jin, Y.; Sun, N.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, J. Post-synthetic modification of porous organic cages. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 8874-86.

9. Hu, D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, M. Recent advances in the applications of porous organic cages. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 11333-46.

10. Tozawa, T.; Jones, J. T.; Swamy, S. I.; et al. Porous organic cages. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 973-8.

11. Wang, Z.; He, X.; Yong, T.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhong, T. B. Multicolor tunable polymeric nanoparticle from the tetraphenylethylene cage for temperature sensing in living cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 512-9.

12. Chen, L.; Li, C.; Fu, E.; et al. A donor–acceptor cage for thermally activated delayed fluorescence: toward a new kind of TADF exciplex emitters. ACS. Mater. Lett. 2023, 5, 1450-5.

13. Acharyya, K.; Mukherjee, P. S. A fluorescent organic cage for picric acid detection. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 15788-91.

14. Dong, J.; Pan, Y.; Yang, K.; et al. Enhanced biological imaging via aggregation-induced emission active porous organic cages. ACS. Nano. 2022, 16, 2355-68.

15. Liyana Gunawardana, V. W.; Ward, C.; Wang, H.; et al. Crystalline nanoparticles of water-soluble covalent basket cages (CBCs) for encapsulation of anticancer drugs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202306722.

16. Pérez-Márquez, L. A.; Perretti, M. D.; García-Rodríguez, R.; Lahoz, F.; Carrillo, R. A fluorescent cage for supramolecular sensing of 3-nitrotyrosine in human blood serum. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2022, 61, e202205403.

17. Lin, C. Y.; Hsu, C. H.; Hung, C. M.; et al. Entropy-driven charge-transfer complexation yields thermally activated delayed fluorescence and highly efficient OLEDs. Nat. Chem. 2024, 16, 98-106.

18. Zahra, T.; Javeria, U.; Jamal, H.; Baig, M. M.; Akhtar, F.; Kamran, U. A review of biocompatible polymer-functionalized two-dimensional materials: emerging contenders for biosensors and bioelectronics applications. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2024, 1316, 342880.

19. Lustig, W. P.; Mukherjee, S.; Rudd, N. D.; Desai, A. V.; Li, J.; Ghosh, S. K. Metal-organic frameworks: functional luminescent and photonic materials for sensing applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 3242-85.

20. Wang, S.; Li, H.; Huang, H.; Cao, X.; Chen, X.; Cao, D. Porous organic polymers as a platform for sensing applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 2031-80.

21. Raja Lakshmi, P.; Nanjan, P.; Kannan, S.; Shanmugaraju, S. Recent advances in luminescent metal–organic frameworks (LMOFs) based fluorescent sensors for antibiotics. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 435, 213793.

22. Dey, S.; Hasan, M.; Shukla, A.; et al. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence and room-temperature phosphorescence in asymmetric phenoxazine-quinoline (D2–A) conjugates and dual electroluminescence. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2022, 126, 5649-57.

23. Tao, Y.; Yuan, K.; Chen, T.; et al. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials towards the breakthrough of organoelectronics. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 7931-58.

24. Zhang, H.; Zhao, Z.; Turley, A. T.; et al. Aggregate science: from structures to properties. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2001457.

25. Maji, S.; Samanta, J.; Samanta, K.; Natarajan, R. Emissive click cages. Chemistry 2023, 29, e202301985.

26. Qiu, F.; Chen, X.; Wang, W.; Su, K.; Yuan, D. Highly stable sp2 carbon-conjugated porous organic cages. CCS. Chem. 2024, 6, 149-56.

27. Montà-González, G.; Sancenón, F.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Martí-Centelles, V. Purely covalent molecular cages and containers for guest encapsulation. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 13636-708.

28. Borse, R. A.; Tan, Y.; Yuan, D.; Wang, Y. Progress of porous organic cages in photo/electrocatalytic energy conversion and storage applications. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 1307-29.

29. Guo, Z.; Li, G.; Wang, H.; et al. Drum-like metallacages with size-dependent fluorescence: exploring the photophysics of tetraphenylethylene under locked conformations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9215-21.

30. Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Guo, Y.; et al. Topological effect on fluorescence emission of tetraphenylethylene-based metallacages. Chinese. Chemical. Letters. 2023, 34, 108531.

31. Feng, H. T.; Yuan, Y. X.; Xiong, J. B.; Zheng, Y. S.; Tang, B. Z. Macrocycles and cages based on tetraphenylethylene with aggregation-induced emission effect. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7452-76.

32. Wang, H.; Zhao, E.; Lam, J. W.; Tang, B. Z. AIE luminogens: emission brightened by aggregation. Mater. Today. 2015, 18, 365-77.

33. Zou, D.; Li, Z.; Long, D.; et al. Molecular cage with dual outputs of photochromism and luminescence both in solution and the solid state. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 13545-53.

34. Zheng, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, C.; et al. Self-assembly of a highly emissive pure organic imine-based stack for electroluminescence and cell imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4704-10.

35. Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Feng, R.; et al. Reticular modulation of piezofluorochromic behaviors in organic molecular cages by replacing non-luminous components. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202403646.

36. Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Tan, L.; et al. A porous tricyclooxacalixarene cage based on tetraphenylethylene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 9244-8.

37. Duan, H.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; et al. Host-guest recognition and fluorescence of a tetraphenylethene-based octacationic cage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 10101-10.

38. Duan, H.; Cao, F.; Hao, H.; Bian, H.; Cao, L. Efficient photoinduced energy and electron transfers in a tetraphenylethene-based octacationic cage through host-guest complexation. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 16837-45.

39. Feng, X.; Liao, P.; Jiang, J.; Shi, J.; Ke, Z.; Zhang, J. Perylene diimide based imine cages for inclusion of aromatic guest molecules and visible-light photocatalysis. ChemPhotoChem 2019, 3, 1014-9.

40. Konopka, M.; Cecot, P.; Ulrich, S.; Stefankiewicz, A. R. Tuning the solubility of self-assembled fluorescent aromatic cages using functionalized amino acid building blocks. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 503.

41. Bhandari, P.; Ahmed, S.; Saha, R.; Mukherjee, P. S. Enhancing fluorescence in both solution and solid states induced by imine cage formation. Chemistry 2024, 30, e202303101.

42. Drożdż, W.; Bouillon, C.; Kotras, C.; et al. Generation of multicomponent molecular cages using simultaneous dynamic covalent reactions. Chemistry 2017, 23, 18010-8.

43. Wang, Z.; Ma, H.; Zhai, T. L.; et al. Networked cages for enhanced CO2 capture and sensing. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800141.

44. Cheng, L.; Liu, K.; Duan, Y.; et al. Adaptive chirality of an achiral cage: chirality transfer, induction, and circularly polarized luminescence through aqueous host–guest complexation. CCS. Chem. 2021, 3, 2749-63.

45. Xu, W.; Duan, H.; Chang, X.; et al. Polyanion and anionic surface monitoring in aqueous medium enabled by an ionic host-guest complex. Sens. Actuators. B. Chem. 2021, 340, 129916.

46. Duan, H.; Cao, F.; Zhang, M.; Gao, M.; Cao, L. On-off-on fluorescence detection for biomolecules by a fluorescent cage through host-guest complexation in water. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 2459-63.

47. Duan, Y.; Wang, J.; Cheng, L.; et al. A fluorescent, chirality-responsive, and water-soluble cage as a multifunctional molecular container for drug delivery. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 3998-4005.

48. Cao, F.; Duan, H.; Li, Q.; Cao, L. A tetraphenylethene-based hexacationic molecular cage with an open cavity. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 13389-92.

49. Duan, H.; Yang, T.; Li, Q.; Cao, F.; Wang, P.; Cao, L. Recognition and chirality sensing of guanosine-containing nucleotides by an achiral tetraphenylethene-based octacationic cage in water. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 108878.

50. Zhao, Y.; Niu, R.; Guo, F.; et al. White light emissive tetraphenylethene molecular cage-based hybrid nanoparticles for intracellular long-term imaging. ACS. Appl. Nano. Mater. 2024, 7, 14549-56.

51. Zhu, Z. H.; Zhang, D.; Chen, J.; et al. A biocompatible pure organic porous nanocage for enhanced photodynamic therapy. Mater. Horiz. 2023, 10, 4868-81.

52. An, L.; De, L. T. P.; Smith, P. T.; Narouz, M. R.; Chang, C. J. Synergistic porosity and charge effects in a supramolecular porphyrin cage promote efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202209396.

53. Kagan, N. E.; Mauzerall, D.; Marrifield, R. B. strati-Bisporphyrins. A novel cyclophane system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 5484-6.

54. Cen, T.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, S. Flexible porphyrin cages and nanorings. J. Porphyrins. Phthalocyanines. 2018, 22, 726-38.

55. Liu, C.; Liu, K.; Wang, C.; et al. Elucidating heterogeneous photocatalytic superiority of microporous porphyrin organic cage. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1047.

56. Hong, S.; Rohman, M. R.; Jia, J.; et al. Porphyrin boxes: rationally designed porous organic cages. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 13241-4.

57. Chen, H.; Roy, I.; Myong, M. S.; et al. Triplet-triplet annihilation upconversion in a porphyrinic molecular container. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 10061-70.

58. Shi, Y.; Cai, K.; Xiao, H.; et al. Selective extraction of C70 by a tetragonal prismatic porphyrin cage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13835-42.

59. An, J. M.; Kim, S. H.; Kim, D. Recent advances in two-photon absorbing probes based on a functionalized dipolar naphthalene platform. Org. Biomol. Chem. , 2020, 4288-97.

60. Liu, C.; Jin, Y.; Qi, D.; et al. Enantioselective assembly and recognition of heterochiral porous organic cages deduced from binary chiral components. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 7014-20.

61. Huang, H. H.; Song, K. S.; Prescimone, A.; et al. Porous shape-persistent rylene imine cages with tunable optoelectronic properties and delayed fluorescence. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 5275-85.

62. Jia, F.; Hupatz, H.; Yang, L. P.; et al. Naphthocage: a flexible yet extremely strong binder for singly charged organic cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4468-73.

63. Jia, F.; Schröder, H. V.; Yang, L. P.; et al. Redox-responsive host-guest chemistry of a flexible cage with naphthalene walls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 3306-10.

64. Xu, Z.; Singh, N. J.; Kim, S. K.; Spring, D. R.; Kim, K. S.; Yoon, J. Induction-driven stabilization of the anion-π interaction in electron-rich aromatics as the key to fluoride inclusion in imidazolium-cage receptors. Chemistry 2011, 17, 1163-70.

65. Wang, F.; Wang, K.; Kong, Q.; et al. Recent studies focusing on the development of fluorescence probes for zinc ion. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 429, 213636.

66. Sun, N.; Qi, D.; Jin, Y.; et al. Porous pyrene organic cage with unusual absorption bathochromic-shift enables visible light photocatalysis. CCS. Chem. 2022, 4, 2588-96.

67. Ge, C.; Shang, W.; Chen, Z.; et al. Self-assembled pure covalent tubes exhibiting circularly polarized luminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202408056.

68. Li, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, M.; et al. Two pyrene-based cagearene constitutional isomers: synthesis, separation, and host–guest chemistry. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 4992-6.

69. Al Kelabi, D.; Dey, A.; Alimi, L. O.; Piwoński, H.; Habuchi, S.; Khashab, N. M. Photostable polymorphic organic cages for targeted live cell imaging. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 7341-6.

70. Dai, C.; Xu, Y.; Liu, B.; Gu, B. Organic cages with dual emission promoted by cage-like structure for ratiometric sensing of hypochlorous acid. Microchem. J. 2024, 204, 110967.

71. Dai, C.; Qian, H. L.; Yan, X. P. Facile room temperature synthesis of ultra-small sized porous organic cages for fluorescent sensing of copper ion in aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125860.

72. Dai, C.; Gu, B.; Tang, S. P.; Deng, P. H.; Liu, B. Fluorescent porous organic cage with good water solubility for ratiometric sensing of gold(III) ion in aqueous solution. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2022, 1192, 339376.

73. Mastalerz, M.; Schneider, M. W.; Oppel, I. M.; Presly, O. A salicylbisimine cage compound with high surface area and selective CO2/CH4 adsorption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 1046-51.

74. Schneider, M. W.; Oppel, I. M.; Ott, H.; et al. Periphery-substituted [4+6] salicylbisimine cage compounds with exceptionally high surface areas: influence of the molecular structure on nitrogen sorption properties. Chemistry 2012, 18, 836-47.

75. Alexandre, P. E.; Zhang, W. S.; Rominger, F.; Elbert, S. M.; Schröder, R. R.; Mastalerz, M. A robust porous quinoline cage: transformation of a [4+6] salicylimine cage by povarov cyclization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 19675-9.

76. Bureš, F. Fundamental aspects of property tuning in push–pull molecules. RSC. Adv. 2014, 4, 58826-51.

77. Šimon, P.; Klikar, M.; Burešová, Z.; et al. Centripetal triazine chromophores: towards efficient two-photon absorbers and highly emissive polyimide films. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2023, 11, 7252-61.

78. Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, H.; et al. Photophysical properties of intramolecular charge transfer in a tribranched donor-π-acceptor chromophore. Chemphyschem 2015, 16, 2357-65.

79. Padalkar, V. S.; Patil, V. S.; Sekar, N. Synthesis and photo-physical properties of fluorescent 1,3,5-triazine styryl derivatives. Chem. Cent. J. 2011, 5, 77.

80. Zhang, H.; Ao, Y. F.; Wang, D. X.; Wang, Q. Q. Triazine- and binaphthol-based chiral macrocycles and cages: synthesis, structure, and solid-state assembly. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 3491-7.

81. Ding, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, B.; et al. Targeted synthesis of a large triazine-based [4+6] organic molecular cage: structure, porosity and gas separation. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 1976-9.

82. Liu, Z.; Deng, C.; Su, L.; et al. Efficient intramolecular charge-transfer fluorophores based on substituted triphenylphosphine donors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 15049-53.

83. Yu, Q.; Zhu, Q. Design and synthesis of triphenylphosphine-based donor-π-acceptor fluorophores with strong aggregation-induced emission and enantiomer-paired flower-like stacking. Dyes. Pigm. 2024, 223, 111903.

84. Gajula, R. K.; Mohanty, S.; Chakraborty, M.; Sarkar, M.; Prakash, M. J. An imine linked fluorescent covalent organic cage: the sensing of chloroform vapour and metal ions, and the detection of nitroaromatics. New. J. Chem. 2021, 45, 4810-22.

85. Ren, H.; Liu, C.; Ding, X.; Fu, X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, J. High fluorescence porous organic cage for sensing divalent palladium ion and encapsulating fine palladium nanoparticles. Chin. J. Chem. 2022, 40, 385-91.

86. Hu, Y.; Yao, J.; Xu, Z.; et al. Three-dimensional organic cage with narrowband delayed fluorescence. Sci. China. Chem. 2020, 63, 897-903.

87. Wang, Z. C.; Tan, Y. Z.; Yu, H.; Bao, W. H.; Tang, L. L.; Zeng, F. A benzothiadiazole-based self-assembled cage for cadmium detection. Molecules 2023, 28, 1841.

88. Zhang, R. F.; Hu, W. J.; Liu, Y. A.; et al. A shape-persistent cryptand for capturing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 5649-54.

89. Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q. P.; Guo, F.; et al. Self-similar chiral organic molecular cages. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 670.

90. Zhao, X.; Cui, H.; Guo, L.; et al. General and modular synthesis of covalent organic cages for efficient molecular recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202411613.

91. Xu, Z.; Ye, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Jiang, S. Design and assembly of porous organic cages. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 2261-82.

92. Brand, M. C.; Trowell, H. G.; Pegg, J. T.; et al. Photoresponsive organic cages-computationally inspired discovery of azobenzene-derived organic cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 30332-9.

93. Berardo, E.; Greenaway, R. L.; Miklitz, M.; Cooper, A. I.; Jelfs, K. E. Computational screening for nested organic cage complexes. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2020, 5, 186-96.

94. Trzaskowski, B.; Martínez, J. P.; Sarwa, A.; Szyszko, B.; Goddard, W. A. 3rd. Argentophilic interactions, flexibility, and dynamics of pyrrole cages encapsulating silver(I) clusters. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2024, 128, 3339-50.

95. Tarzia, A.; Wolpert, E. H.; Jelfs, K. E.; Pavan, G. M. Systematic exploration of accessible topologies of cage molecules via minimalistic models. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 12506-17.

96. Santolini, V.; Miklitz, M.; Berardo, E.; Jelfs, K. E. Topological landscapes of porous organic cages. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 5280-98.

97. Berardo, E.; Turcani, L.; Miklitz, M.; Jelfs, K. E. An evolutionary algorithm for the discovery of porous organic cages. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 8513-27.

98. Turcani, L.; Tarzia, A.; Szczypiński, F. T.; Jelfs, K. E. stk: An extendable Python framework for automated molecular and supramolecular structure assembly and discovery. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154, 214102.

99. Turcani, L.; Berardo, E.; Jelfs, K. E. stk: A python toolkit for supramolecular assembly. J. Comput. Chem. 2018, 39, 1931-42.

100. Berardo, E.; Greenaway, R. L.; Turcani, L.; et al. Computationally-inspired discovery of an unsymmetrical porous organic cage. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 22381-8.

101. Jones, J. T.; Hasell, T.; Wu, X.; et al. Modular and predictable assembly of porous organic molecular crystals. Nature 2011, 474, 367-71.

102. Slater, A. G.; Reiss, P. S.; Pulido, A.; et al. Computationally-guided synthetic control over pore size in isostructural porous organic cages. ACS. Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 734-42.

103. Del Regno, A.; Siperstein, F. R. Organic molecules of intrinsic microporosity: characterization of novel microporous materials. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 2013, 176, 55-63.

104. Evans, J. D.; Huang, D. M.; Hill, M. R.; et al. Molecular design of amorphous porous organic cages for enhanced gas storage. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015, 119, 7746-54.

105. Abbott, L. J.; McDermott, A. G.; Del Regno, A.; et al. Characterizing the structure of organic molecules of intrinsic microporosity by molecular simulations and X-ray scattering. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013, 117, 355-64.

106. Jiang, S.; Jelfs, K. E.; Holden, D.; et al. Molecular dynamics simulations of gas selectivity in amorphous porous molecular solids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 17818-30.

107. Miklitz, M.; Jelfs, K. E. pywindow: automated structural analysis of molecular pores. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2018, 58, 2387-91.

108. Miklitz, M.; Jiang, S.; Clowes, R.; Briggs, M. E.; Cooper, A. I.; Jelfs, K. E. Computational screening of porous organic molecules for xenon/krypton separation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2017, 121, 15211-22.

109. Chen, L.; Reiss, P. S.; Chong, S. Y.; et al. Separation of rare gases and chiral molecules by selective binding in porous organic cages. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 954-60.

110. Zhao, D.; Wang, Y.; Su, Q.; Li, L.; Zhou, J. Lysozyme adsorption on porous organic cages: a molecular simulation study. Langmuir 2020, 36, 12299-308.

111. Day, G. M.; Cooper, A. I. Energy-structure-function maps: cartography for materials discovery. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1704944.

112. Gayathri, P.; Pannipara, M.; Al-Sehemi, A. G.; Anthony, S. P. Triphenylamine-based stimuli-responsive solid state fluorescent materials. New. J. Chem. 2020, 44, 8680-96.

113. Luo, W.; Wang, G. Photo-responsive fluorescent materials with aggregation-induced emission characteristics. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 2001362.

114. Hu, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Ma, D.; Huang, F. Three-dimensional organic cage with aggregation-induced delayed fluorescence. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 1017-9.

115. Yu, H.; Luo, Y.; Luo, S.; et al. A reusable fluorescent molecular self-assembly cage for simultaneous detection and recycling of silver(I) ion. Chem. Asian. J. 2024, 19, e202300872.

116. Ren, H.; Liu, C.; Yang, W.; Jiang, J. Sensitive and selective sensor based on porphyrin porous organic cage fluorescence towards copper ion. Dyes. Pigm. 2022, 200, 110117.

117. Zhao, X.; Xiong, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. A hexapyrrolic molecular cage and the anion-binding studies in chloroform. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1293, 136232.

118. Bian, L.; Tang, M.; Liu, J.; Liang, Y.; Wu, L.; Liu, Z. Luminescent chiral triangular prisms capable of forming double helices for detecting traces of acids and anion recognition. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2022, 10, 15394-9.

119. Pan, J.; Lin, W.; Bao, F.; et al. Multiple fluorescence color transitions mediated by anion-π interactions and C-F covalent bond formation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107519.

120. Della-Negra, O.; Kouassi, A. E.; Dutasta, J. P.; Saaidi, P. L.; Martinez, A. Fluorescence detection of the persistent organic pollutant chlordecone in water at environmental concentrations. Chemistry 2023, 29, e202203887.