Coupling of photocatalysis with traditional catalysis to facilitate the conversion of carbohydrates

Abstract

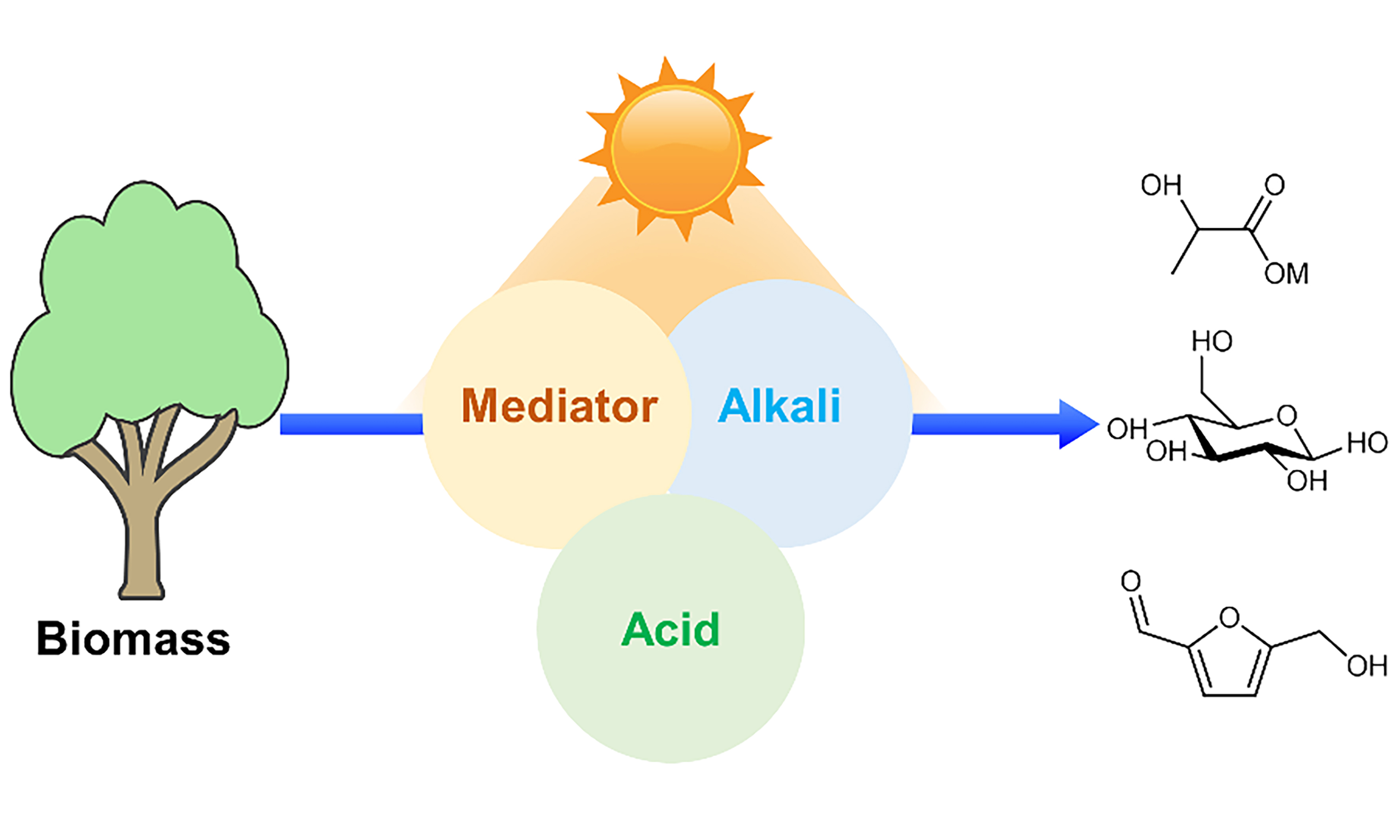

Photocatalysis has been increasingly investigated as an alternative approach to traditional catalysis for biomass conversions, though both strategies have advantages and disadvantages. Herein, we present an overview on the coupling of photocatalysis with traditional catalysis and their applications in the conversion of biomass-derived carbohydrates to value-added chemicals. These applications include: (1) modulation of an adscititious oxidant and in situ generated mediator to boost the photocatalytic oxidation of carbohydrates to chemicals; (2) coupling of photocatalysis with basic catalysis to facilitate the conversion of carbohydrates to lactic acid with H2 production; and (3) coupling of photocatalysis with acid catalysis for the polysaccharide hydrolysis to monosaccharides, glucose isomerization to fructose and dehydration to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. We believe that the rational combination of photocatalysis with traditional catalysis would not only provide an effective strategy for the design and development of more effective catalytic systems for biomass conversions, but also create new opportunities for synergetic utilization of material and energy.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The irresponsible linear consumption of fossil resources with huge emissions of greenhouse gas (GHG) and persistent accumulation of pollutants is a 21st century challenge. Using renewable and readily available biomass resources as raw materials to displace fossil resources is a promising solution to these challenges[1]. On the one hand, biomass utilization could greatly facilitate GHG reduction, owing to the capture of CO2 in photosynthesis[2,3]. In this context, various technologies have been investigated to convert biomass to value-added chemicals, fuels, and polymers with the purpose of partially reducing or even fully substituting the existing commodities made from non-renewable fossil resources and other unsustainable resources, forming a conceptual framework of biorefinery[4,5].

Lignocellulosic biomass primarily comprises cellulose, hemicelluloses, lignin, fatty acids, lipids, proteins, and other components[6-8], with carbohydrates fraction (35-50 wt% cellulose, 20-30 wt% hemicelluloses) constituting the major feedstocks for biorefinery[9]. Cellulose is a macromolecular polysaccharide consisting of glucose monomers via β-1,4-glycosidic bonds, while hemicelluloses are branched polysaccharides mainly composed of xylose with a few other sugars, such as mannose, galactose, rhamnose, and arabinose[10-12]. To facilitate the conversion of biomass to the desired product, pretreatment is usually required to partly remove lignin and reduce the recalcitrance of lignocellulosic biomass[13]. Subsequently, the cellulose-rich fraction can be subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis or acidic catalytic hydrolysis to obtain glucose which can be isomerized to value-added fructose or converted to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) for the production of diverse high-value products, while the partial depolymerized hemicelluloses could be used for the production of xylose and furfural via acidic catalyzed hydrolysis and dehydration. Although the elementary paths for the conversion of carbohydrates to value-added products have been clearly established, these conversions universally suffer from low reaction efficiency, low selectivity, and high energy consumption.

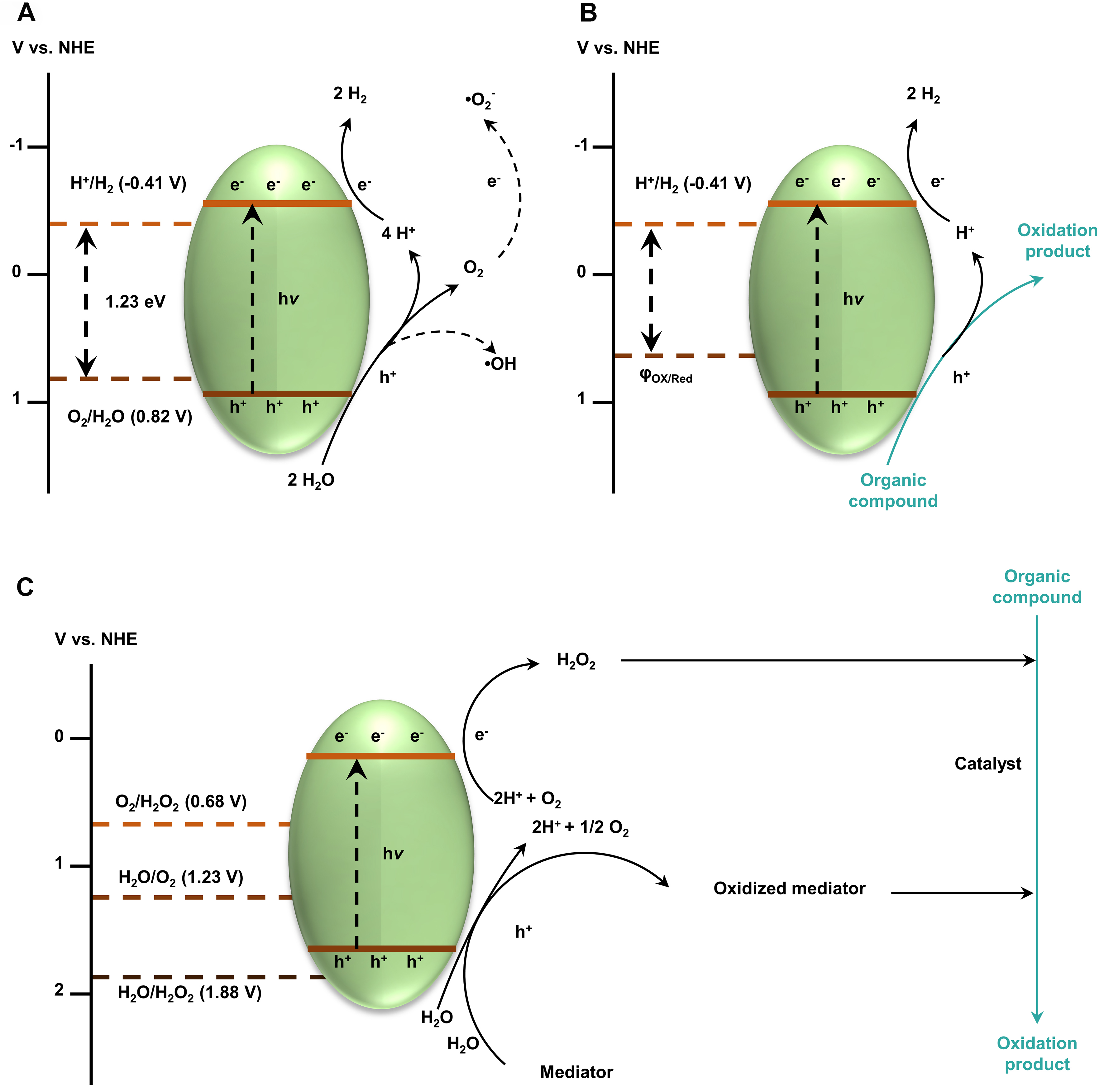

As an enormous, sustainable, and clean energy resource to be unearthed[14], sunlight has been increasingly investigated for the conversion of biomass. Under optical radiation, the semiconductor materials adsorb the energy of photons to produce photogenerated charge carriers, including electron (e-) and hole (h+) when the wavelength of photons is smaller than the band gap width of semiconductor materials. Subsequently, the photogenerated charge carriers over the catalyst evolve into reactive species to drive the oxidation or reduction process under mild reaction conditions. The photocatalysis conversion is generally performed under mild reaction conditions or even without external heat, with great promise to reduce energy consumption. Moreover, photocatalytic reaction provides an effective approach for the precise tailoring of specific chemical bonds or functionalization of specific functional groups[15]. In this context, photocatalytic conversion of biomass, including selective oxidation or reduction of biomass-derived chemicals, and photocatalytic hydrogen production with biomass as sacrificial agents have been extensively studied in the past decades. The research progress of the photocatalytic transformation of lignocellulosic biomass has been comprehensively summarized in previous reviews[15-22]. Nevertheless, photocatalytic biomass conversions also suffer from a series of defects, such as low efficiency of mass transfer, high consumption of sacrificial agent and severe side-reaction, due to the limited optical adsorption of semiconductor materials, the rapid recombination of photogenerated charge carriers and the generation of multifarious reactive species to actuate multiple reaction pathways. Recently, increasing research has been devoted to the combination of photocatalysis with traditional catalysis to create new opportunities to further facilitate the conversion of carbohydrates.

Herein, we aim to provide a conceptual framework for the coupling of photocatalysis with traditional catalysis by summing up the recent development of the catalytic systems and their applications in conversion of biomass-derived carbohydrates to value-added chemicals. First, we reviewed the progress of photocatalytic oxidation of carbohydrates, with an emphasis on the modulation of adscititious oxidant and in situ generated mediator. Second, we summarize the coupling of photocatalysis with basic catalysis to facilitate the conversion of carbohydrates to lactic acid (LA) with H2 production. Third, we summarize the coupling of photocatalysis with acid catalysis for polysaccharide hydrolysis, sugar isomerization and dehydration.

OXIDATION OF CARBOHYDRATES TO CHEMICALS

Oxidation of glucose could deliver value-added gluconic acid (GA) and glucaric acid (GAA) which have been broadly employed in various fields[23]. Due to the presence of multiple highly reactive functional groups and the complex spatial structure of glucose, selective oxidation of glucose into the target product is highly challenging. Current oxidation methods [Table 1] generally suffer from low conversion efficiency and poor selectivity, and depend on the use of noble metals-based materials of high cost[24,25], which restricts large-scale production and application. Photocatalysis offers an effective approach for low-cost and efficient conversion. However, common semiconductor materials such as TiO2 exhibit inferior catalytic performance for glucose oxidation [Table 1][26-28], due to the recombination of photogenerated carriers and uncontrollable generation of various radicals, including hydroxyl radicals (·OH) which may lead to the mineralization of target products. Some noble metals or photosensitizing materials may mediate the selective transformation of oxidants into active radicals with moderate oxidation capabilities, thereby markedly enhancing the selectivity of the oxidation process. For example, loading cobalt phthalocyanine (CoPz)[29,30] and iron phthalocyanine (FePz)[31,32] onto semiconductor materials could not only improve the separation efficiency of photogenerated charge carriers but also suppress the formation of ·OH radicals. Thus, a glucose conversion of 52.1% with a total selectivity of GA and GAA up to 79.4% was obtained.

Photocatalytic oxidation of carbohydrates to chemicals

| Catalyst | Substrate | Solvent | Light source | Oxidant | Reaction conditions | Alkaline additive | Conversion | Selectivity | Ref. |

| 3% Au/TiO2, 25 g/L | Glucose, 0.1 mM | H2O | UV light of Xe lamp, | - | 30 °C, 4 h | 0.1 mM Na2CO3 | 99% | GA 94% | [24] |

| 3%Au/TiO2, 25 g/L | Glucose, 0.1 mM | H2O | Visible light of Xe lamp, | - | 30 °C, 4 h | 0.1 mM Na2CO3 | 99% | GA 99% | [24] |

| 0.68% Au/TiO2, 0.5 g/L | Glucose, 50 g/L | H2O | 1.1 equiv. H2O2, | 10 min | 0.3 M NaOH | 49% | GA 81% | [25] | |

| Glucose, 50 g/L | H2O | 1.1 equiv. H2O2 | 10 min | 0.3 M NaOH | 69% | GA 95% | [25] | ||

| TiO2, 1 g/L | Glucose, 2.8 mM | mercury lamp, 125 W | - | 30 °C, 10 min | - | 11.0% | GA/GAA/arabitol 71.3% | [26] | |

| TiO2, 1 g/L | Glucose, 1 g/L | mercury lamp, | - | 30 min | - | 69.5% | GA 8.6% | [27] | |

| TiO2, 0.875 g/L | Glucose, 2.8 mM | Xe lamp (λ > 420 nm), | - | 4 h | - | 42% | GA 7% | [28] | |

| TiO2/HPW(29%)/ CoPz(1%), 1 g/L | Glucose, 5 mM | H2O | Xe lamp, | - | 3 h | - | 22.2% | GA 63.5%, GAA 16.9% | [29] |

| g-C3N4/CoPz(0.5%), 0.67 g/L | Glucose, 1 mM | H2O | Xe lamp, | 9.8 mM H2O2 | 20 min | - | 52.1% | GA + GAA 79.4% | [30] |

| Glucose, 1 mM | H2O | Xe lamp, | 400 mL/min air | 3 h | - | 34.2% | GA 32.9%, GAA 12.9% | [31] | |

| H-ZSM-5/FePz(SBu)8, | Glucose, 3 mM | H2O | Visible light of Xe lamp, | 9.9 mM H2O2 | 4 h | - | 35.8% | GA 31.9%, GAA 13.1% | [32] |

| CNK-OH, 1 g/L | Glucose, 1 g/L | H2O | Xe lamp, | 2 mM TEMPO | 12 h | 1 M KOH | 100% | GAA ~30% | [33] |

| CNKS-OH, 2 /L | Cellobiose, 2 g/L | 0.1 M H2SO4 | Xe lamp, | 2 mM TEMPO | 90 °C, 6 h | - | ~80% | GA ~70% | [33] |

| Ce6@BNCN, 0.33 g/L | Glucose, 1 mM | H2O | Xe lamp, | 9.8 mM H2O2 | 2 h | - | 62.3% | GA 47.3%, GAA 12.3% | [37] |

| Fe1CN-20, | Glucose, 0.5 mM | H2O | Xe lamp, | 1 mM PMS | 30 min | - | 36.3% | GA 91.6% | [38] |

| RCN, 1 g/L | Glucose, 2 g/L | H2O | Xe lamp, | - | 5 h | - | 60.7% | GA 40% | [41] |

Photocatalytic conversion of cellobiose, the building block of cellulose, has been achieved with potassium and sulfur co-doped carbon nitride (CNKS) under heating (90 °C) and acidic conditions (0.1 M H2SO4), giving GA selectivity more than 70% at cellobiose conversion higher than 80%[33]. Glucose oxidation with carbon nitride photocatalyst has also been integrated with cellulose hydrolysis over cellulase enzymes to enable sequential cascade conversion of cellulose to GA in a one-pot catalytic system, affording cellulose conversion more than 75% with > 75% GA selectivity in relative to the generated glucose[34].

Effective activation of oxidants is a prerequisite for achieving selective oxidation of organic compounds[35,36]. In addition to air or O2, additional oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and peroxymonosulfate (PMS) have also been investigated to boost photocatalytic oxidation. We constructed a metal-free photocatalyst (BNCN@Ce6) consisting of nitrogen-deficient carbon nitride (BNCN) with chlorin e6 (Ce6) to facilitate selective oxidation of glucose with H2O2 as the oxidant[37]. This composite obtained a total selectivity of GA, GAA and arabinose of up to 70.9% at a glucose conversion of 62.3%. The combination of experimental results and theoretical calculation suggested that the good catalytic performance of BNCN@Ce6 is owing to the improved optical absorption ability, better separation efficiency of photon-generated carriers, and higher glucose adsorption ability with reduced adsorption of major products. Subsequently, we found that the importing of single-atom iron onto carbon nitride could also notably improve the light absorption and the separation efficiency of photogenerated carriers to promote the selective oxidation of glucose[38]. The single-atom iron supported on carbon nitride (Fe1CN) enabled the effective activation of peroxymonosulfate (PMS) towards reactive oxygen species, with 1O2 as the main species to promote glucose oxidation, attaining GA as high as 91.6% at glucose conversion of 36.3% within

Except for additional oxidants, some chemicals might function as mediators which could shuttle between ordinary and oxidation states to boost the steerable oxidation process. Recently, H2O2 and

Furthermore, alkali-modified carbon nitride (CNK-OH) as a catalyst could work synergistically with TEMPO as a mediator to enable highly selective oxidation of glucose towards GAA, firstly obtaining a GAA yield of 30% with glucose conversion of achieving 100%[45]. It was induced that the oxidation of aldehyde groups of both glucose and glucuronic acid is induced by CNK-OH and simultaneous production of H2O2. In contrast, the primary alcohol group linked to the C6 site of GA was selectively oxidized to glucuronic acid by TEMPO+ species derived from the reaction of TEMPO with photogenerated holes. The generated TEMPOH could react with •O2- to recover TEMPO, accompanied by the release of HOO- ions. However, GA became the main product when the catalyst was reused, indicating the irreversible loss of catalytic activity. In this research, both H2O2 and TMEPO function as oxidative mediators to facilitate the target selective oxidation. With the recent boom of photocatalytic systems for H2O2 synthesis, their coupling with selective oxidation may grow rapidly in the near future [Figure 1].

COUPLING OF PHOTOCATALYSIS WITH BASIC CATALYSIS

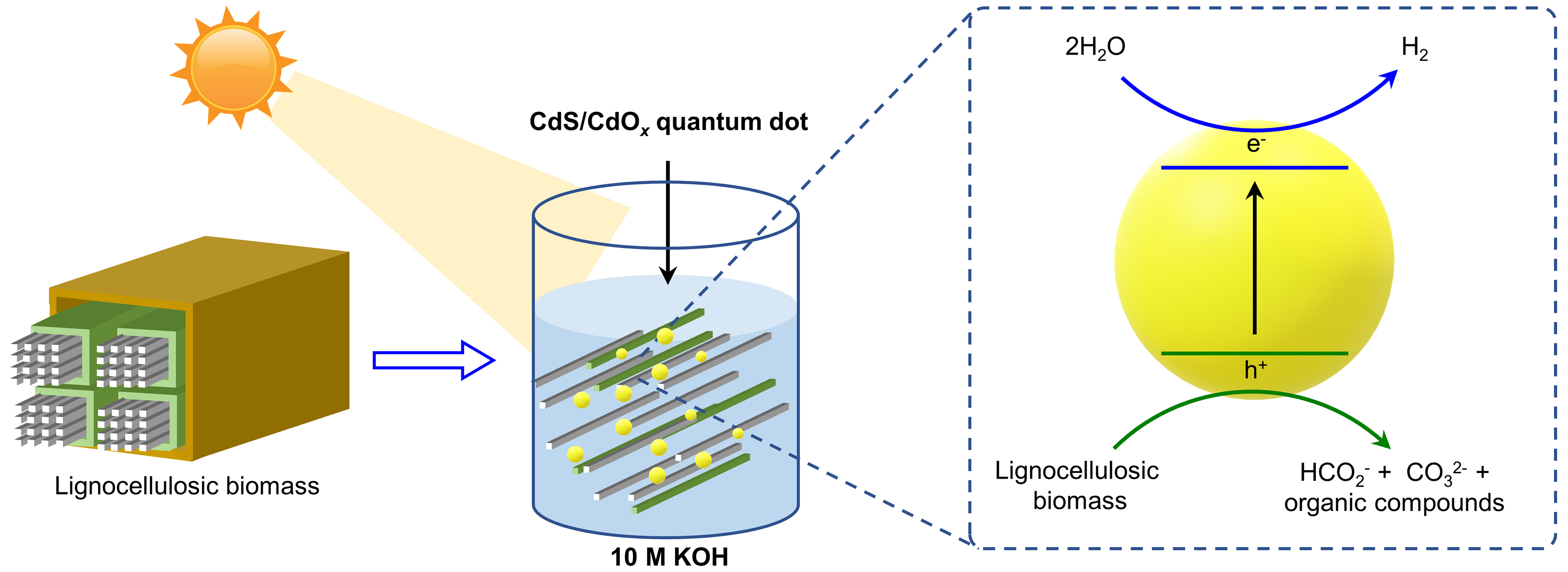

Photocatalytic oxidation of biomass to valuable chemicals coupled with H2 production via water splitting over semiconductors is an effective strategy to improve the utilization efficiency of solar energy. In early studies on photocatalytic hydrogen production, simple biomass-derived chemicals, particularly glucose, were widely used as a sacrificial agent that functions as an electron donor in the oxidation half-reaction to scavenge holes [Table 2][46]. Compared to overall water splitting for hydrogen production, coupling the hydrogen production process with the oxidation of organic compounds can significantly lower the reaction energy barrier, thus enhancing hydrogen production efficiency[17]. Using native biomass as a starting material for hydrogen production is an effective way to reduce the cost of feedstocks, but they suffer from low productivity due to the limitation of mass transfer between solid-solid phases[47]. Using SO42- and NiS co-modified TiO2 as catalysts, the hydrogen production efficiency could be improved via the synergistic effect of acid catalysis and photocatalysis to promote the decomposition of cellulose. In the medium of 10 M KOH solution, the strong alkaline environment could expedite the swelling and partial dissolution of cellulose while the CdS/CdOx quantum dot photocatalyst allows the direct conversion of biomass along with the formation of H2 [Figure 2][48-50]. However, these systems were primarily designed for hydrogen production, with a limited understanding of the oxidation processes and low selectivity for high-value oxidation products[51-58].

Figure 2. Photocatalytic conversion of native biomass in strong alkaline environment. Redraw according to Ref.[48].

Photocatalytic H2 production with carbohydrates as sacrificial agent

| Catalyst and dosage | Substrate concentration | Solvent | Light source | Time | Alkaline additive | Product | H2 productivity | Ref. |

| RuO2/TiO2/Pt | Sucrose, 15 g/L | H2O | Xe lamp, 500 W | 20 h | NaOH, 6 M | - | 56.8 μmol/g/h | [46] |

| RuO2/TiO2/Pt | Starch, 3 g/L | H2O | Xe lamp, 500 W | 20 h | NaOH, 6 M | - | 40.7 μmol/g/h | [46] |

| RuO2/TiO2/Pt | Cellulose | H2O | Xe lamp, 500 W | 20 h | NaOH, 6 M | - | 12.2 μmol/g/h | [46] |

| CdS/CdOx, | α-cellulose, 50 g/L | H2O | A.M.1.5 g, | 24 h | NaOH, 10 M | Organic substrates, CO2 | 4.2 μmol/g/h | [48] |

| Glucose, 5 wt% | H2O | Xe lamp, 300 W | 4 h | - | - | ~1.9 μmol/g/h | [51] | |

| ZnS-ZnIn2S4, | Glucose, 0.1 M | H2O | Metal halide lamp (> 420 nm), | 10 h | NaOH, | Degradation intermediates such as gluconic acid | 10.3 μmol/g/h | [52] |

| Pt0.5Au1.5/CN, 0.33 g/L | Glucose, 3 g/L | H2O | Xe lamp, 300 W (170 mW/cm2) | 3 h | - | Arabinose, glucuronic acid, formic acid, lactic acid, propionic acid, etc. | 90.4 μmol/g/h | [53] |

| 3DOM CTO-ZCS, 0.15 g/L | Glucose, 0.1 M | H2O | Xe lamp, 300 W | 5 h | NaOH, 1 M | Gluconic acid, lactic acid | 281 μmol/g/h | [57] |

| THM, 0.5 g/L | Glucose, 1 g/L | H2O/CH3CN | Xe lamp, 300 W | 2 h | Na2CO3, | Arabinose, formic acid | 944 μmol/g/h | [54] |

| PRCN, 1.5 g/L | Glucose, 2 g/L | H2O | Xe lamp, 300 W | 2 h | - | Fructose | 72 μmol/g/h | [55] |

| RuS2@CN, | Xylose, 3.33 g/L | H2O | LED light (380-760 nm), 10 W | 5 h | KOH, 5 M | Lactic acid | [58] | |

| K/O@CN-CuN, 0.33 g/L | Xylose, 5 g/L | H2O | LED light (380-760 nm), 10 W | 5 h | KOH, 5 M | Lactic acid | [56] |

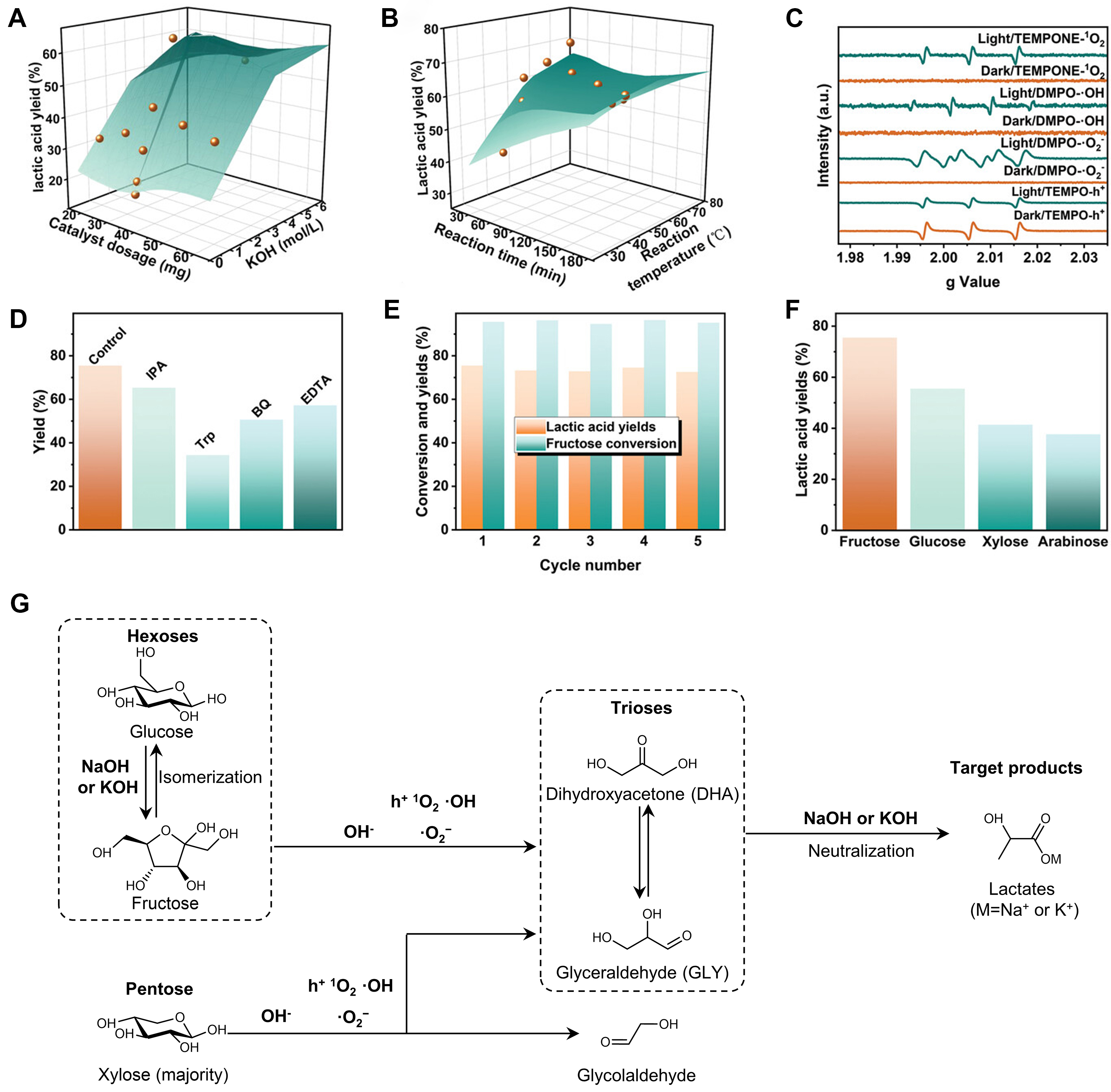

The in-depth investigations on oxidation products have revealed that the combination of photocatalysis with strong alkaline environment could generally convert simple sugars toward LA [Table 3], which virtually should be present in the form of sodium lactate or potassium lactate. Various doped, modified carbon nitride and related composites, such as boron and oxygen-doped carbon nitride (B@mCN-Y)[59], ultrathin porous carbon nitride (Ut-OCN)[60] and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) co-doped with zinc/oxygen atoms (Zn2/O@IP-g-CN)[61] have been designed to improve the light absorption capacity and boost the separation efficiency of photogenerated carriers, compared with g-C3N4. With these photocatalysts, high LA yields have been achieved from both pentoses (xylose, arabinose) and hexoses (fructose, glucose, mannose, rhamnose). The rigorous comparison between photocatalytic reaction and dark reaction has demonstrated the crucial roles of photocatalytic processes. The radical scavenging experiments in these studies indicated that h+, 1O2, ·O2- and ·OH are all involved in the production of LA, with ·O2- having the highest contribution rate. The alkali concentration also has a critical influence on the reaction, as is in accordance with the phenomenon observed with the thermal catalytic conversion of sugars to LA over homogenous alkalis[62]. KOH or NaOH is generally required to obtain high LA yields [Figure 3]. When a relatively low concentration of alkali was used in these photocatalytic systems, the isomerization of glucose to fructose occurred to a great extent with low LA yield, as is consistent with the catalytic performance of individual alkali without photocatalyst[63-65]. In contrast, excessive alkali inevitably led to the decrease of target product. Taken together, the indiscriminate conversion of pentoses and hexoses to LA in photocatalytic systems should be attributed to the combined action of photocatalysis and basic catalysis. First, the alkali at suitable concentration could not only induce the isomerization of glucose to fructose and the retro-aldol reaction of fructose to C3 intermediates, but also capture LA as chemically stable lactate salts to avoid their degradation. Second, it was deduced that the reactive oxygen species, in particular ·O2-, could also assist the retro-aldol reaction of pentoses and hexoses toward intermediates [Figure 3G]. Third, the strong alkaline environment could reduce the oxidation ability of ·OH and h+ to suppress over-oxidation. Eventually, the synergy of photocatalysis and basic catalysis results in the conversion of simple sugars to lactate salts. Besides, photothermal effect that could expedite reaction rate under relatively mild temperatures has been observed in several catalysts, such as N-TiO2[66], g-C3N4/N-TiO2/NiFe-layered double hydroxide (LDH) (NTCN/LDH)[67].

Figure 3. Photocatalytic conversion of monosaccharides in strong alkaline environment. The effects of different conditions on the synthesis of LA: (A) catalyst dosage and KOH concentration; (B) reaction temperature and time; (C) ESR spectra; (D) influence of different scavengers; (E) recycling experiment and (F) reaction substrates. Adapted with permission from Ref.[68], Wiley; (G) The possible reaction pathways. ESR: Electron spin resonance.

Photocatalytic conversion of carbohydrates to LA under strong alkaline environment

| Catalyst | Solvent | Conditions | Feedstock | Conversion | Yield | TOF | Ref. |

| RuS2@CN, 1.67 wt% | 5 M KOH | 30 °C, 5 h, Visible light (10 w), Ar | Glucose, 0.33 wt% | - | 29% | - | [58] |

| RuS2@CN, 1.67 wt% | 5 M KOH | 30 °C, 5 h, Visible light (10 w), Ar | Arabinose, 0.33 wt% | - | 91.5% | - | [58] |

| K/O@CN-C≡N, 0.33 wt% | 5 M KOH | 30 °C, 6 h, Visible light (10 w) | Glucose, 0.75 wt% | 88% | 63.6% | - | [56] |

| K/O@CN-C≡N, 0.33 wt% | 5 M KOH | 30 °C, 6 h, Visible light (10 w) | Xylose, 0.75 wt% | 95% | 86.6 | - | [56] |

| B@mCN, 3 wt% | 2 M KOH | 60 °C, 1.5 h, Xe lamp | Glucose, 1 wt% | > 99% | 77% | - | [59] |

| B@mCN, 3 wt% | 2 M KOH | 60 °C, 1.5 h, Xe lamp | Arabinose, 1 wt% | > 99% | 92.7% | - | [59] |

| Ut-OCN, 6 wt% | 3 M KOH | 50 °C, 1.5 h, Visible light | Glucose, 1 wt% | > 96.9% | 63.9% | - | [60] |

| Ut-OCN,6 wt% | 3 M KOH | 50 °C, 1.5 h, Visible light | Xylose, 1 wt% | > 99% | 89.7% | - | [60] |

| Znx/O@IP-g-CN, 1 wt% | 5 M KOH | 60 °C, 6 h, LED lights (5 w), Ar | Glucose, 0.5 wt% | 100% | 91.91% | - | [61] |

| Znx/O@IP-g-CN, 1 wt% | 5 M KOH | 60 °C, 6 h, LED lights (5 w), Ar | Xylose, 0.5 wt% | 100% | 92.6% | - | [61] |

| N-TiO2, 1 wt% | 2 M KOH | 60 °C, 2 h, Solar simulated light (10 w) | Glucose, 1 wt% | > 99% | 84.9% | - | [66] |

| N-TiO2, 1 wt% | 2 M KOH | 60 °C, 2 h, Solar simulated light (10 w) | Pyruvaldehyde, 1 wt% | > 99% | 98.8% | - | [66] |

| NTCN/LDH, 1 wt% | 1 M KOH | 60 °C, 1 h, LED lights (10 w) | Glucose, 1 wt% | > 99% | 92% | [67] | |

| NTCN/LDH, 1 wt% | 1 M KOH | 60 °C, 1 h, LED lights (10 w) | Pyruvaldehyde, 1 wt% | 100% | 99% | [67] | |

| HCN, 4 wt% | 2 M KOH | 50 °C, 1.5 h, Xe lamp | Glucose, 1 wt% | - | 55.49% | - | [68] |

| HCN, 4 wt% | 2 M KOH | 50 °C, 1.5 h, Xe lamp | Fructose, 1 wt% | 95.6% | 75.5% (2.8 mmol/h/g H2) | - | [68] |

| K/S@CN, 0.5 wt% | 0.5 M KOH | 30 °C, 12 h, Visible light (10 w), CO2 | Glucose, 0.75 wt% | - | 41.4% | - | [69] |

| K/S@CN, 0.5 wt% | 0.5 M KOH | 30 °C, 12 h, Visible light (10 w), CO2 | Xylose, 0.75 wt% | - | 75.8% | - | [69] |

| Zn-mCN, 3.3 wt% | 7 M KOH | 30 °C, 5 h, Visible light (10 w), Ar | Glucose, 1 wt% | - | 43.2% | - | [70] |

| Zn-mCN, 3.3 wt% | 7 M KOH | 30 °C, 5 h, Visible light (10 w), Ar | Xylose, 1 wt% | - | 89.6% | - | [70] |

| TiO2@MC, 1.25 wt% | 3 M KOH | 50 °C, 1 h, Visible light | Xylose, 1 wt% | - | 49.22% | - | [71] |

| CuO@CS, 0.42 wt% | 1.5 M KOH | 60 °C, 1 h, Visible light | Glucose, 1 wt% | 98.2% | 54.2% | - | [72] |

| CuO@CS, 0.42 wt% | 1.5 M KOH | 60 °C, 1 h, Visible light | Xylose, 1 wt% | 100% | 81.6% | - | [72] |

| Bi/Bi2O3@N-BC, 1 wt% | 2 M KOH | 60 °C, 0.75 h, Visible light | Glucose, 1 wt% | > 99% | 73.44% | - | [73] |

| Bi/Bi2O3@N-BC, 1 wt% | 2 M KOH | 60 °C, 0.75 h, Visible light | Xylose, 1 wt% | 100% | 91.21% | - | [73] |

| Cu/Cu2O/CuO@CA, | 2 M KOH | 60 °C, 0.42 h, Visible light | Glucose, 1 wt% | 99% | 66.46% | - | [74] |

| Cu/Cu2O/CuO@CA, | 2 M KOH | 60 °C, 0.42 h, Visible light | Xylose, 1 wt% | > 99% | 92.76% | - | [74] |

| CC1@mCN10, 4 wt% | 2 M KOH | 60 °C, 1 h, Visible light | Glucose, 1 wt% | 100% | 69.9% | - | [75] |

| CC1@mCN10, 4 wt% | 2 M KOH | 60 °C, 1 h, Visible light | Xylose, 1 wt% | 100% | 76.8% | - | [75] |

| BP-s-CN, 0.167 wt% | 5 M KOH | 25 °C, 6 h, LED lights, Ar | Glucose, 0.5 wt% | - | 31.9% | - | [76] |

| BP-s-CN, 0.167 wt% | 5 M KOH | 25 °C, 6 h, LED lights, Ar | Arabinose, 0.5 wt% | - | 74.4% | - | [76] |

| PACN, 1 wt% | 0.3 M KOH | 30 °C, 9 h, LED lights, Ar | Glucose, 1 wt% | - | 37.9`% | - | [77] |

| PACN, 1 wt% | 0.3 M KOH | 30 °C, 9 h, LED lights, Ar | Xylose, 1 wt% | - | 63.32% | - | [77] |

| Fe@GaN, 0.5 wt% | 1 M KOH | 25 °C, 6 h, Visible light | Xylose, 1 wt% | - | 71.38% | - | [78] |

| 4CzIPN@CMC-HG | 8 M KOH | Glucose, 1 wt% | > 99% | 58.5% | - | [79] | |

| 4CzIPN@CMC-HG | 8 M KOH | 50 °C, 2.3 h, 300 w Xe lamp | Xylose, 1 wt% | 100% | 90.8% | - | [79] |

| CQDs@4CzIPN, 1 wt% | 2 M KOH | 70 °C, 0.5 h, Visible light | Glucose, 1 wt% | > 99% | 71% | - | [80] |

| CQDs@4CzIPN, 1 wt% | 2 M KOH | 70 °C, 0.5 h, Visible light | Xylose, 1 wt% | > 99% | 92.7% | - | [80] |

The photocatalytic synthesis of LA has also been successfully integrated with H2 production and CO2 reduction. Zou et al. synthesized 1D holey g-C3N4 nanorods (HCN) via cellulose nanofiber-assisted polymerization, and achieved LA yield of 75.5% and H2 generation rate of 2.822 mmol/h/g[68]. Potassium and sulfur dual sites modified crystalline carbon nitride (K/S@CN-x) with improved visible-light absorption and photogenerated charge separation efficiency was successfully prepared via salt-template-assisted incorporation method, to actuate synchronous LA synthesis from sugars and CO2 reduction[69]. A LA of 78.07% was achieved from xylose under a relatively mild alkaline environment (0.5 M KOH), with a carbon monoxide (CO) production rate of 16.27 μmol·g-1·h-1. Co-production of hydrogen and LA has also been achieved by photocatalytic reaction under a strong alkaline environment.

Although high apparent LA yields have been obtained from both pentoses and hexoses using various photocatalytic materials[71-80], several bottlenecks impede practical applications. First and foremost, these systems often require the addition of homogeneous alkali in quantities several times greater than the biomass substrate. In the industrial fermentation process, the production of LA consumes large amounts of calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) and mineral (sulfuric) acid, along with the generation of one ton of gypsum as solid wastes per ton of LA product[81]. In contrast, the use of excess alkali in photocatalytic systems will not only complicate product separation but also introduce secondary pollution due to the high consumption of mineral acid and base. Second, there are several controversies about the reaction pathways for LA formation. In previous reports, the term “photocatalytic oxidation” has been frequently used to describe the conversion of sugars to LA. However, the transformation of one mole of hexose (C6H12O6) to two moles of LA (C3H6O3) could be considered as a decomposition process with 100% atom economy, without electron transfer from adscititious oxidants. Therefore, the photocatalytic conversion of sugars to LA seems to be more likely disproportionation reaction which may only involve intramolecular electron transfer, which needs to be explored in future studies.

COUPLING OF PHOTOCATALYSIS WITH ACIDIC CATALYSIS

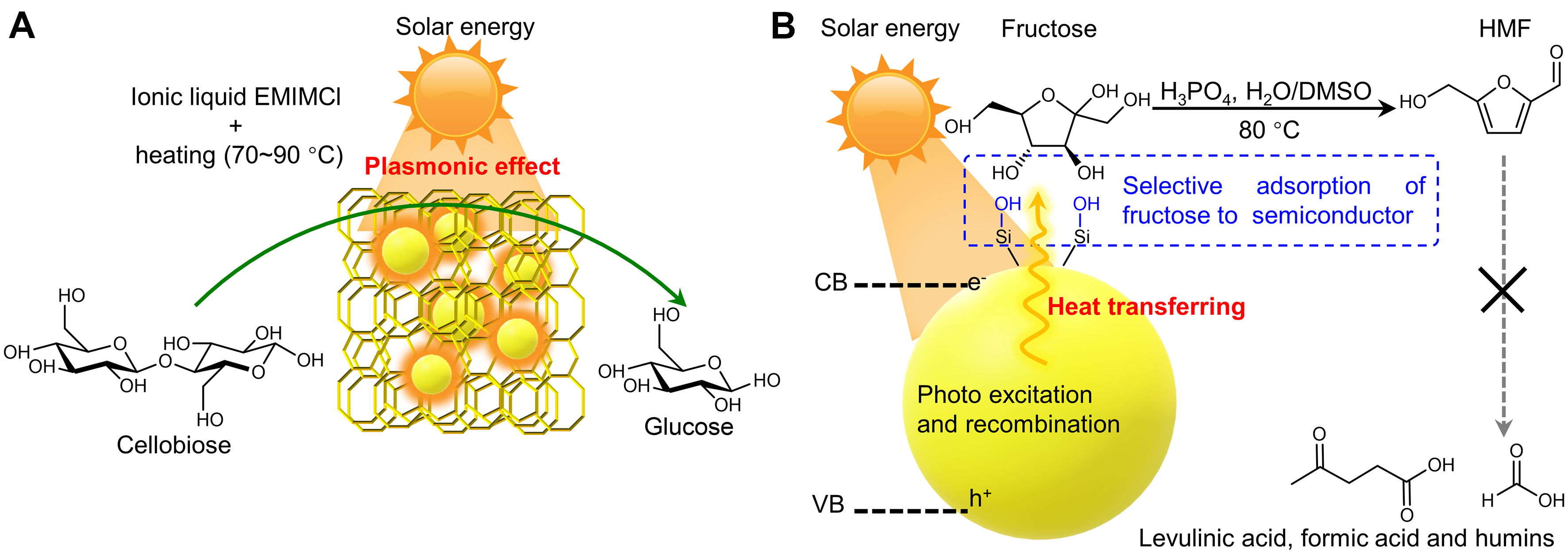

The combination of photocatalysis with acidic catalysis might facilitate reaction via multiple mechanisms, such as expediting thermocatalytic reaction by improving reaction temperature via photothermal effect, enhancing the intensity of acidic sites by regulating their coordination environments, and regulating the rate and sequence of different reaction pathways. Photothermal catalysts generally convert solar energy to heat via three kinds of mechanisms, including plasmonic localized heating, non-radiative relaxation of semiconductors, and thermal vibration in molecules[14]. Using light as heat to impulse chemical reactions, photothermal catalysis may combine the photo- and thermo-chemical processes to boost reaction rates and to change reaction pathways, even under mild reaction conditions[82]. Owing to the localized heating effect around the catalytic active center, photothermal catalysis may afford reaction rate remarkably higher than photocatalysis and thermal catalysis[83-87]. Photothermal effect has also been used to promote the cleavage of β-1,4-glycosidic bonds to facilitate the hydrolysis of cellobiose and cellulose [Figure 4A][88]. Two kinds of materials, Ir/HY and Ir/Amberlyst-15, combine Ir nanoparticles as the plasmonic photothermal source with acidic sites to enable selective hydrolysis of cellobiose and non-pretreated crystalline cellulose [Table 4] in the medium of ionic liquid 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride (EMIMCl) under mild temperatures (70-90 °C), more than 40 °C lower than the temperature required for the reaction in the dark. It should be noted that EMIMCl, as a typical cellulose-dissolvable ionic liquid, is also crucial for effective hydrolysis, since the dissolution of cellulose could reduce the barrier of mass transfer between catalyst and substrate.

Photothermal assisted hydrolysis of cellobiose and cellulose

| Catalyst | Solvent | Condition | Substrate loading | Conversion | Yield | Ref. |

| Ir/HY, 1 wt% | H2O/EMIMCl (1/10) | 90 °C, 9 h, 300 W Xe lamp (> 420 nm) | Cellobiose, 1 wt% | 85% | - | [88] |

| Ir/HY, 1 wt% | H2O/EMIMCl (1/10) | 100 °C, 8 h, dark | Cellobiose, 1 wt% | ~30% | - | [88] |

| HY, 1 wt% | H2O/EMIMCl (1/10) | 100 °C, 8 h, 300 W Xe lamp (> 420 nm) | Cellobiose, 1 wt% | 34% | - | [88] |

| HY, 1 wt% | H2O/EMIMCl (1/10) | 100 °C, 8 h, 300 W Xe lamp (> 420 nm) | Cellobiose, 1 wt% | 31% | - | [88] |

| Ir/Amberlyst-15, | H2O/EMIMCl (1/10) | 70 °C, 5 h, 300 W Xe lamp (> 420 nm) | Cellobiose, 1 wt% | 85% | - | [88] |

| Ir/HY, 1 wt% | H2O/EMIMCl (1/10) | 90 °C, 13 h, 300 W Xe lamp (> 420 nm) | Cellulose, 1 wt% | - | Cellobiose 10.9%, Glucose 40.4%, HMF 24% | [88] |

| Ir/Amberlyst-15, | H2O/EMIMCl (1/10) | 90 °C, 9 h, 300 W Xe lamp (> 420 nm) | Cellulose, 1 wt% | - | Cellobiose 13.7%, Glucose 54.1%, HMF 5.4% | [88] |

Selective conversion of carbohydrates into 5-HMF is an attractive and promising route for value-added utilization of biomass resources[89], but this conversion faces the trade-off between low reaction rate under moderate temperate and severe side-reaction under evaluated temperate. The introduction of unconventional strategy is very imperative to overcome this bottleneck. The conversion of fructose to HMF is a relatively simple dehydration process catalyzed by Brønsted acid. For example, a silanol groups-coated silicon semiconductor (Si-OH) has been used as a photothermal catalyst to assist the fructose dehydration to HMF with 4.6 M H3PO4 as an acid catalyst and DMSO/H2O as a solvent [Figure 4B][90]. HMF yield as high as 97% [Table 5] was achieved at 80 °C which is markedly lower than that of conventional acidic catalytic systems under oil heating. The superior performance results from the preferential adsorption of fructose onto Si-OH along with the rapid desorption of HMF. Thus, the heat generated on Si-OH under visible light irradiation could selectively activate fructose but without impacting HMF, eventually leading to selective dehydration of fructose to HMF with few degradations of the target product. As the isomeride of fructose, glucose is much more abundant in nature and cheaper than fructose. However, the conversion of glucose to HMF involves more complicated pathways, including glucose isomerization to fructose over Lewis acid sites and fructose dehydration over Brønsted acid sites. To convert glucose to HMF, Cr3+ ions and Ag particles were immobilized on Al2O3 nanofibers to boost Lewis acidity and light absorption ability[91]. The Ag particles improved the reaction rate by 13.4 times owing to the heating effect of localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) with visible-light irradiation. A 68% yield of HMF was obtained under moderate temperatures

Conversion of carbohydrates to HMF via coupled photocatalysis and acidic catalysis

| Catalyst | Solvent | Condition | Substrate loading | Conversion | Yield | Productivity | Ref. |

| Si-OH 0.9 wt%; 4.6 M H3PO4 | H2O/DMSO (1/1) | 80 °C, 5 h, xenon lamp | Fructose, 0.9 wt% | - | 97% | - | [90] |

| Si-OH 0.9 wt%; 4.6 M H3PO4 | H2O/DMSO (1/1) | 80 °C, 5 h, no photoirradiation | Fructose, 0.9 wt% | - | 63% | - | [90] |

| Si (99%) 0.9 wt%; 4.6 M H3PO4 | H2O/DMSO (1/1) | 80 °C, 5 h, xenon lamp | Fructose, 0.9 wt% | - | 59% | - | [90] |

| Si (99.999%) 0.9 wt%; 4.6 M H3PO4 | H2O/DMSO (1/1) | 80 °C, 5 h, xenon lamp | Fructose, 0.9 wt% | - | 45% | - | [90] |

| Ag-G-Al2O3-Cr3+, 1 wt% | H2O/DMSO (40/1) | 70 °C, 20 h, halogen light | Glucose, 1.3 wt% | - | 68% | TON 91 | [91] |

| Ag-G-Al2O3-Cr3+, 1 wt% | H2O/DMSO (40/1) | 70 °C, 20 h, dark, argon | Glucose, 1.3 wt% | - | < 0.1% | - | [91] |

| Ag-G-Al2O3-Cr3+, 1 wt% | DMSO | 70 °C, 20 h, halogen light (1 W·cm-2), argon | Glucose, 1.3 wt% | - | 39% | TON 52 | [91] |

| G-Al2O3-Cr3+, 1 wt% | DMSO | 70 °C, 20 h, halogen light (1 W·cm-2), argon | Glucose, 1.3 wt% | - | 16% | TON 5.2 | [91] |

| Ag-G-Al2O3, 1 wt% | DMSO | 70 °C, 20 h, halogen light (1 W·cm-2), argon | Glucose, 1.3 wt% | - | 0.1% | - | [91] |

| Al(NO3)3·9H2O 0.01 M, | DMSO | 80 °C, 20 h, halogen light (400-800 nm, 1.2 W·cm-2), argon | Glucose, 0.1 M | - | 59% | - | [92] |

| Al(NO3)3·9H2O 0.01 M, | DMSO | 80 °C, 20 h, dark, argon | Glucose, 0.1 M | - | 6% | - | [92] |

| Al(NO3)3·9H2O 0.01 M | DMSO | 80 °C, 20 h, halogen light (400-800 nm, 1.2 W·cm-2), argon | Glucose, 0.1 M | - | 1.3% | - | [92] |

| Al(NO3)3·9H2O 0.01 M | DMSO | 80 °C, 20 h, dark, argon | Glucose, 0.1 M | - | 5% | - | [92] |

| AlCl3·9H2O 0.01 M, 8 g/L fulvic acid | DMSO | 80 °C, 20 h, halogen light (400-800 nm, 1.2 W·cm-2), argon | Glucose, 0.1 M | - | 50% | - | [92] |

| Al2(SO4)3·9H2O 0.01 M, | DMSO | 80 °C, 20 h, halogen light (400-800 nm, 1.2 W·cm-2), argon | Glucose, 0.1 M | - | 0 | - | [92] |

| DMSO | 80 °C, 20 h, halogen light (400-800 nm, 1.2 W·cm-2), argon | Glucose, 0.1 M | - | 0 | - | [92] | |

| Al(NO3)3·9H2O 0.01 M, 4 g/L pyrogallol | DMSO | 70 °C, 20 h, halogen light (400-800 nm, 0.9 W·cm-2), argon | Glucose, 0.1 M | - | 67% | - | [92] |

| Al(NO3)3·9H2O 0.01 M, 8 g/L catechol | DMSO | 70 °C, 20 h, halogen light (400-800 nm, 0.9 W·cm-2), argon | Glucose, 0.1 M | - | 70% | - | [92] |

| Ru/HY-SO3H, 0.4 wt% | H2O/[C2mim]Cl/MIBK | 120 °C, 3 h, 300 W Xe lamp (> 420 nm) | Cellulose, 0.4 wt% | - | 48% | - | [94] |

| G-A-Ga3+, 1 wt% | DMSO | 80 °C, 4 h, 1 W/cm2 | Glucose, 1.8 wt% | - | 58% | TON 100% | [93] |

| G-A-Ga3+, 1 wt% | DMSO | 80 °C, 4 h, 1 dark | Glucose, 1.8 wt% | - | 0.4% | - | [93] |

| G-A-Ga3+, 0.05 wt% | DMSO | 80 °C, 20 h, 1 W/cm2 | Glucose, 14.4 wt% | - | 36% | TON 1,500 | [93] |

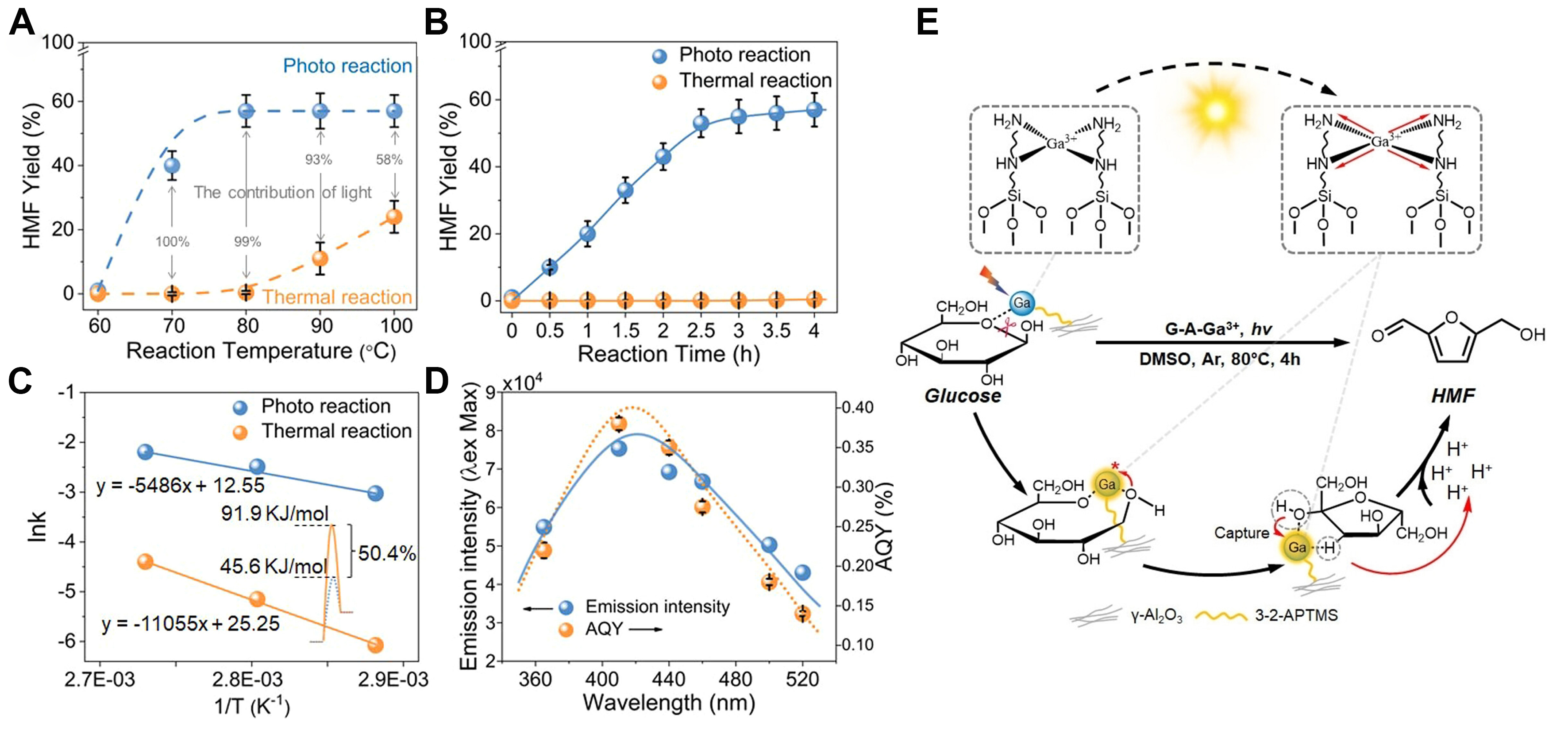

The combination of Al3+ ions with the component ligands of fulvic acid as light antennas under visible light enabled one-pot conversion of glucose to HMF under mild reaction conditions without using adscititious Brønsted acid, affording HMF yield of 60% at 80 °C[92]. When catechol and pyrogallol, two of the typical constituents of fulvic acid, were employed as light-absorbing antennas and ligands to complex with Al3+ ions, the HMF yields could be further improved to 67% and 70% at 70 °C. Analogously, the anchor of Ga(III) onto alumina nanofibers (G-A-Ga3+) via coordination with N-donor ligands enabled significantly improved light absorption[93]. Under photoirradiation, the electron density between gallium(III) and N-donor ligands is redistributed and a semi-coordination state is formed via ligand to metal charge transfer [Figure 5], greatly boosting the Lewis acidity of the catalyst and the interaction of sugar molecules with gallium(III) active sites. Consequently, the HMF yield and the reaction rate of HMF formation were significantly higher than the equivalent thermal reaction system and the homogeneous gallium(III) system. It should be noted that the catalysts used in these systems are not semiconductor materials and the conversion is simple dehydration, instead of photocatalytic redox processes. The solar energy is either converted to heating or used to enhance the intensity of acidic sites.

Figure 5. Photocatalytic conversion of glucose to HMF. (A) Temperature dependence for the conversion of glucose to HMF; (B) Time course of the yield of HMF using G-A-Ga3+ at 80 °C; (C) Contributions to the activation energy of light irradiation on the conversion; (D) The relationship between AQY of G-A-Ga3+ at different wavelengths and the fluorescence spectrum of G-A-Ga3+; (E) Mechanism of photoinduced conversion. Adapted with permission from Ref.[93], Wiley. HMF: Hydroxymethylfurfural.

The one-pot conversion of cellulose to 5-HMF includes consecutive cellulose hydrolysis to glucose, glucose isomerization and fructose dehydration by different sites. Several multifunctional composites, including Ru/HY-SO3H[94], palygorskite-based Cu2(PO4)(OH) composite[95] and TiO2/g-C3N4/SO3H(IL)[96], have also designed for the visible-light-driven conversion of cellulose to 5-HMF. The use of Ru/HY-SO3H as a catalyst under 300 W Xe lamp combined with a biphasic medium (ionic liquid/methyl isobutyl ketone) enabled the efficient conversion of cellulose to 5-HMF with a yield of 48.4% at 120 °C.

As proof of concept, these studies have demonstrated the feasibility of integrating photocatalysis with acidic catalysis to quicken the conversion of both fructose and glucose into high HMF yields under much lower temperatures. All three kinds of mechanisms, including improvement of temperature via photothermal effect, enhancement of acidic sites, and regulation of reaction pathways, have been demonstrated, providing an important direction for the further development of acidic dehydration systems. However, these catalytic systems still require low substrate loading, long reaction time and high-boiling point solvent, indicating that the actual reaction efficiency remains low. Meanwhile, the ultimate HMF yield and selectivity of coupled catalytic systems are comparable to those of traditional acidic systems, suggesting that the reaction efficiency is not improved substantially and the bottleneck of this reaction is not significantly changed. Whether this strategy could achieve yield and reaction efficiency significantly higher than conventional catalytic systems in green solvents needs further investigation. Crucially, the design and development of coupled catalytic systems lack theoretical guidance, since the contributions of conventional heating, localized heating of catalyst surface via photothermal effect and bulk heating of reaction system via photothermal effect are unclear. Meanwhile, the combination of oil heating, light radiation and acidic chemical environments may have more complex influences on the stability and reusability of catalysts, which needs to be investigated in future studies.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

In summary, we have provided an overview on the design and development of catalytic systems that integrate photocatalysis with traditional catalysis for the conversion of carbohydrates to value-added chemicals, including modulation of mediator to boost the photocatalytic selective oxidation, coupling of photocatalysis with basic catalysis for the conversion of carbohydrates to LA and H2 production, and coupling of photocatalysis with acid catalysis for the hydrolysis of carbohydrates and dehydration of carbohydrates to HMF. These advances have proved the feasibility and great potential of integrating photocatalysis with conventional catalysis to improve reaction efficiency, regulate reaction pathways or deal with awkward biomass feedstocks. Nevertheless, this strategy is still in its early stages and numerous challenges need to be addressed.

For selective oxidation, precisely controlling the generation and fully using the reactive oxygen species via the rational design of catalytic system are necessary to further improve the reaction efficiency. Particularly, the screening of more effective mediators with both high density and long operational lifetimes is expected to achieve the selective oxidation of high-concentration feedstocks.

The coupling of photocatalysis with basic catalysis has provided a general approach for the conversion of different monosaccharides to LA with high yields even with synchronous H2 production or CO2 reduction, but their practical applications are limited by dependency on excess alkali. The authentic reaction pathway of different sugars and the contribution of basic catalysis and photocatalysis to different elementary steps, including isomerization, retro-aldol condensation and capture of LA product, need to be revealed with rigorous benchmarking tests. Based on this, the required loading of alkali may be reduced, or completely avoided by integrating the strong photocatalytic activity and basic sites into a heterogeneous catalyst.

The coupling of photocatalysis with acid catalysis has successfully achieved the effective hydrolysis of polysaccharides, and conversion of both fructose and glucose into high HMF yields under much lower temperatures than conventional thermal catalysis, owing to the localized heating via surface plasmon resonance effect or the modulation of Lewis acidic sites. However, it should be underlined that these catalytic systems still require low substrate loading, long reaction time and high-boiling point solvent, and the maximal HMF yield is comparable to that of conventional catalysis, indicating the reaction efficiency is not improved substantially. The contributions of conventional heating, localized heating of catalyst surface via photothermal effect and bulk heating of reaction system via photothermal effect are unclear. More efficient and selective coupled catalytic systems should be established by designing multifunctional catalysts with well-defined active sites and photothermal antennae, based on exactly identifying the contributions of acidic catalysis, photocatalysis and their synergistic effect. In addition, the use of green solvents and the influence of coupled processes on the stability and reusability of catalysts need to be investigated, and economic-technical analysis and environmental impact assessment need to be performed in the future.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Writing-review and editing, supervision, conceptualization: Hou, Q.

Investigation: Bai, X.; Wang, C.; Xia, T.; Lai, R.; Tang, Y.; Yu, G.; Qu, F.; Qian, H.; Xie, C.

Supervision, funding acquisition: Ju, M.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22478202, 22208169, U23A20125, 22478203).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Zhu, Y.; Romain, C.; Williams, C. K. Sustainable polymers from renewable resources. Nature 2016, 540, 354-62.

2. Xu, S.; Wang, R.; Gasser, T.; et al. Delayed use of bioenergy crops might threaten climate and food security. Nature 2022, 609, 299-306.

3. Lu, X.; Cao, L.; Wang, H.; et al. Gasification of coal and biomass as a net carbon-negative power source for environment-friendly electricity generation in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116, 8206-13.

4. Song, J.; Chen, C.; Zhu, S.; et al. Processing bulk natural wood into a high-performance structural material. Nature 2018, 554, 224-8.

5. Hou, Q.; Qi, X.; Zhen, M.; et al. Biorefinery roadmap based on catalytic production and upgrading 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Green. Chem. 2021, 23, 119-231.

6. Putten RJ, van der Waal JC, de Jong E, Rasrendra CB, Heeres HJ, de Vries JG. Hydroxymethylfurfural, a versatile platform chemical made from renewable resources. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 1499-597.

7. Corma, A.; Iborra, S.; Velty, A. Chemical routes for the transformation of biomass into chemicals. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2411-502.

8. Liu, W. J.; Li, W. W.; Jiang, H.; Yu, H. Q. Fates of chemical elements in biomass during its pyrolysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 6367-98.

9. Wu, X.; Fan, X.; Xie, S.; et al. Solar energy-driven lignin-first approach to full utilization of lignocellulosic biomass under mild conditions. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 772-80.

10. Zhang, Z.; Song, J.; Han, B. Catalytic transformation of lignocellulose into chemicals and fuel products in ionic liquids. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 6834-80.

11. Petridis, L.; Smith, J. C. Molecular-level driving forces in lignocellulosic biomass deconstruction for bioenergy. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2018, 2, 382-9.

12. Zhang, X.; Wilson, K.; Lee, A. F. Heterogeneously catalyzed hydrothermal processing of C5-C6 sugars. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12328-68.

13. Mostofian, B.; Cai, C. M.; Smith, M. D.; et al. Local phase separation of Co-solvents enhances pretreatment of biomass for bioenergy applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 10869-78.

14. Song, C.; Wang, Z.; Yin, Z.; Xiao, D.; Ma, D. Principles and applications of photothermal catalysis. Chem. Catalysis. 2022, 2, 52-83.

15. Wu, X.; Luo, N.; Xie, S.; et al. Photocatalytic transformations of lignocellulosic biomass into chemicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 6198-223.

16. Liu, X.; Duan, X.; Wei, W.; Wang, S.; Ni, B. Photocatalytic conversion of lignocellulosic biomass to valuable products. Green. Chem. 2019, 21, 4266-89.

17. Feng, S.; Nguyen, P. T. T.; Ma, X.; Yan, N. Photorefinery of biomass and plastics to renewable chemicals using heterogeneous catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202408504.

18. Nwosu, U.; Wang, A.; Palma, B.; et al. Selective biomass photoreforming for valuable chemicals and fuels: a critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy. Rev. 2021, 148, 111266.

19. Sun, L.; Luo, N. Catalyst design and structure control for photocatalytic refineries of cellulosic biomass to fuels and chemicals. J. Energy. Chem. 2024, 94, 102-27.

20. Hang, T.; Wu, L.; Liu, W.; Yang, L.; Zhang, T. Research progress of bifunctional photocatalysts for biomass conversion and fuel production. Adv. Energy. and. Sustain. Res. 2024, 5, 2400069.

21. Xu, X.; Shi, L.; Zhang, S.; et al. Photocatalytic reforming of lignocellulose: a review. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 469, 143972.

22. Skillen, N.; Daly, H.; Lan, L.; et al. Photocatalytic reforming of biomass: what role will the technology play in future energy systems. Top. Curr. Chem. 2022, 380, 33.

23. Yan, W.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Y.; et al. Structural sensitivity of heterogeneous catalysts for sustainable chemical synthesis of gluconic acid from glucose. Chin. J. Catal. 2020, 41, 1320-36.

24. Zhou, B.; Song, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Han, B. Highly selective photocatalytic oxidation of biomass-derived chemicals to carboxyl compounds over Au/TiO2. Green. Chem. 2017, 19, 1075-81.

25. Omri, M.; Sauvage, F.; Busby, Y.; Becuwe, M.; Pourceau, G.; Wadouachi, A. Gold catalysis and photoactivation: a fast and selective procedure for the oxidation of free sugars. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 1635-9.

26. Colmenares, J. C.; Magdziarz, A.; Bielejewska, A. High-value chemicals obtained from selective photo-oxidation of glucose in the presence of nanostructured titanium photocatalysts. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 11254-7.

27. Payormhorm, J.; Chuangchote, S.; Kiatkittipong, K.; Chiarakorn, S.; Laosiripojana, N. Xylitol and gluconic acid productions via photocatalytic-glucose conversion using TiO2 fabricated by surfactant-assisted techniques: effects of structural and textural properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 196, 29-36.

28. Vià L, Recchi C, Gonzalez-yañez EO, Davies TE, Lopez-sanchez JA. Visible light selective photocatalytic conversion of glucose by TiO2. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2017, 202, 281-8.

29. Yin, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, C.; Zhang, B.; Deng, K. Highly selective oxidation of glucose to gluconic acid and glucaric acid in water catalyzed by an efficient synergistic photocatalytic system. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 2231-41.

30. Zhang, Q.; Xiang, X.; Ge, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, B.; Deng, K. Selectivity enhancement in the g-C3N4-catalyzed conversion of glucose to gluconic acid and glucaric acid by modification of cobalt thioporphyrazine. J. Catal. 2020, 388, 11-9.

31. Zhang, Q.; Ge, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, B.; Deng, K. Enhanced photocatalytic performance for oxidation of glucose to value-added organic acids in water using iron thioporphyrazine modified SnO2. Green. Chem. 2019, 21, 5019-29.

32. Chen, R.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Deng, K. Visible-light-driven selective oxidation of glucose in water with H-ZSM-5 zeolite supported biomimetic photocatalyst. J. Catal. 2019, 374, 297-305.

33. Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Chen, L.; et al. Selective cellobiose photoreforming for simultaneous gluconic acid and syngas production in acidic conditions. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2024, 344, 123665.

34. Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Larter, S. R.; Kibria, M. G.; Hu, J. One-pot sequential cascade reaction for selective gluconic acid production from cellulose photobiorefining. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 3451-4.

35. Abednatanzi, S.; Gohari Derakhshandeh, P.; Leus, K.; et al. Metal-free activation of molecular oxygen by covalent triazine frameworks for selective aerobic oxidation. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz2310.

36. Sun, X.; Li, L.; Jin, S.; et al. Interface boosted highly efficient selective photooxidation in Bi3O4Br/Bi2O3 heterojunctions. eScience 2023, 3, 100095.

37. Bai, X.; Hou, Q.; Qian, H.; et al. Selective oxidation of glucose to gluconic acid and glucaric acid with chlorin e6 modified carbon nitride as metal-free photocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2022, 303, 120895.

38. Xia, T.; Ju, M.; Qian, H.; et al. Photocatalytic fenton-like system with atomic Fe on carbon nitride boost selective glucose oxidation towards gluconic acid. J. Catal. 2024, 429, 115257.

39. Lewis, R. J.; Ueura, K.; Liu, X.; et al. Highly efficient catalytic production of oximes from ketones using in situ-generated H2O2. Science 2022, 376, 615-20.

40. Jin, Z.; Wang, L.; Zuidema, E.; et al. Hydrophobic zeolite modification for in situ peroxide formation in methane oxidation to methanol. Science 2020, 367, 193-7.

41. Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Zhao, H.; et al. In situ photo-fenton-like tandem reaction for selective gluconic acid production from glucose photo-oxidation. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 2637-46.

42. Shiraishi, Y.; Takii, T.; Hagi, T.; et al. Resorcinol-formaldehyde resins as metal-free semiconductor photocatalysts for solar-to-hydrogen peroxide energy conversion. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 985-93.

43. Zhang, Y.; Pan, C.; Bian, G.; et al. H2O2 generation from O2 and H2O on a near-infrared absorbing porphyrin supramolecular photocatalyst. Nat. Energy. 2023, 8, 361-71.

44. Teng, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Atomically dispersed low-valent Au boosts photocatalytic hydroxyl radical production. Nat. Chem. 2024, 16, 1250-60.

45. Wang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Z.; et al. Selective photocatalytic glucaric acid production from TEMPO-mediated glucose oxidation on alkalized carbon nitride. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2025, 360, 124526.

46. Kawai, T.; Sakata, T. Conversion of carbohydrate into hydrogen fuel by a photocatalytic process. Nature 1980, 286, 474-6.

47. Wang, J. J.; Li, Z. J.; Li, X. B.; et al. Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution from glycerol and water over nickel-hybrid cadmium sulfide quantum dots under visible-light irradiation. ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 1468-75.

48. Wakerley, D. W.; Kuehnel, M. F.; Orchard, K. L.; Ly, K. H.; Rosser, T. E.; Reisner, E. Solar-driven reforming of lignocellulose to H2 with a CdS/CdOx photocatalyst. Nat. Energy. 2017, 2, BFnenergy201721.

49. Kuehnel, M. F.; Reisner, E. Solar hydrogen generation from lignocellulose. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 3290-6.

50. Uekert, T.; Kuehnel, M. F.; Wakerley, D. W.; Reisner, E. Plastic waste as a feedstock for solar-driven H2 generation. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 2853-7.

51. Luo, N.; Jiang, Z.; Shi, H.; Cao, F.; Xiao, T.; Edwards, P. Photo-catalytic conversion of oxygenated hydrocarbons to hydrogen over heteroatom-doped TiO2 catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2009, 34, 125-9.

52. Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Peng, S.; Lu, G.; Li, S. Photocatalytic hydrogen generation in the presence of glucose over ZnS-coated ZnIn2S4 under visible light irradiation. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2010, 35, 7116-26.

53. Ding, F.; Yu, H.; Liu, W.; et al. Au-Pt heterostructure cocatalysts on g-C3N4 for enhanced H2 evolution from photocatalytic glucose reforming. Materials. &. Design. 2024, 238, 112678.

54. Shi, C.; Eqi, M.; Shi, J.; Huang, Z.; Qi, H. Constructing 3D hierarchical TiO2 microspheres with enhanced mass diffusion for efficient glucose photoreforming under modulated reaction conditions. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2023, 650, 1736-48.

55. Zhang, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhai, S.; et al. Electron-enriched Lewis acid-base sites on red carbon nitride for simultaneous hydrogen production and glucose isomerization. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2022, 316, 121647.

56. Yang, X.; Ma, J.; Sun, S.; Liu, Z.; Sun, R. K/O co-doping and introduction of cyano groups in polymeric carbon nitride towards efficient simultaneous solar photocatalytic water splitting and biorefineries. Green. Chem. 2022, 24, 2104-13.

57. Bai, F. Y.; Han, J. R.; Chen, J.; et al. The three-dimensionally ordered microporous CaTiO3 coupling Zn0.3Cd0.7S quantum dots for simultaneously enhanced photocatalytic H2 production and glucose conversion. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2023, 638, 173-83.

58. Li, X.; Ma, J.; Fu, H.; et al. RuS2@CN-x with exposed (200) facet as a high-performance photocatalyst for selective C–C bond cleavage of biomass coupling with H–O bond cleavage of water to co-produce chemicals and H 2. Green. Chem. 2023, 25, 3236-46.

59. Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, D.; et al. Functional B@mCN-assisted photocatalytic oxidation of biomass-derived pentoses and hexoses to lactic acid. Green. Chem. 2020, 22, 6384-92.

60. Ma, J.; Jin, D.; Li, Y.; et al. Photocatalytic conversion of biomass-based monosaccharides to lactic acid by ultrathin porous oxygen doped carbon nitride. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2021, 283, 119520.

61. Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Jin, D.; Yao, S.; Sun, R. LED white-light-driven photocatalysis for effective lignocellulose reforming to co-produce hydrogen and value-added chemicals via Zn2/O@IP-g-CN. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108554.

62. Li, L.; Shen, F.; Smith, R. L.; Qi, X. Quantitative chemocatalytic production of lactic acid from glucose under anaerobic conditions at room temperature. Green. Chem. 2017, 19, 76-81.

63. Hou, Q.; Rehman, M. L. U.; Bai, X.; et al. Incorporation of MgO into nitrogen-doped carbon to regulate adsorption for near-equilibrium isomerization of glucose into fructose in water. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2024, 342, 123443.

64. Laiq, U. R. M.; Hou, Q.; Bai, X.; et al. Regulating the alkalinity of carbon nitride by magnesium doping to boost the selective isomerization of glucose to fructose. ACS. Sustainable. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 1986-93.

65. Chen, S. S.; Tsang, D. C.; Tessonnier, J. Comparative investigation of homogeneous and heterogeneous Brønsted base catalysts for the isomerization of glucose to fructose in aqueous media. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2020, 261, 118126.

66. Cao, Y.; Chen, D.; Meng, Y.; Saravanamurugan, S.; Li, H. Visible-light-driven prompt and quantitative production of lactic acid from biomass sugars over a N-TiO2 photothermal catalyst. Green. Chem. 2021, 23, 10039-49.

67. Ding, Y.; Cao, Y.; Chen, D.; et al. Relay photo/thermal catalysis enables efficient cascade upgrading of sugars to lactic acid: mechanism study and life cycle assessment. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139687.

68. Zou, R.; Chen, Z.; Zhong, L.; et al. Nanocellulose-assisted molecularly engineering of nitrogen deficient graphitic carbon nitride for selective biomass photo-oxidation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2301311.

69. Liu, Z.; Ma, J.; Hong, M.; Sun, R. Potassium and sulfur dual sites on highly crystalline carbon nitride for photocatalytic biorefinery and CO2 reduction. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 2106-17.

70. Ma, J.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Single-atom zinc catalyst for co-production of hydrogen and fine chemicals in soluble biomass solution. Adv. Powder. Mater. 2022, 1, 100058.

71. Liu, K.; Ma, J.; Yang, X.; et al. Boosting electron kinetics of anatase TiO2 with carbon nanosheet for efficient photo-reforming of xylose into biomass-derived organic acids. J. Alloys. Compd. 2022, 906, 164276.

72. Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Jin, D.; et al. Copper oxide functionalized chitosan hybrid hydrogels for highly efficient photocatalytic-reforming of biomass-based monosaccharides to lactic acid. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2021, 291, 120123.

73. Jin, D.; Ma, J.; Sun, R. Nitrogen-doped biochar nanosheets facilitate charge separation of a Bi/Bi2O3 nanosphere with a Mott-Schottky heterojunction for efficient photocatalytic reforming of biomass. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2022, 10, 3500-9.

74. Jin, D.; Jiao, G.; Ren, W.; Zhou, J.; Ma, J.; Sun, R. Boosting photocatalytic performance for selective oxidation of biomass-derived pentoses and hexoses to lactic acid using hierarchically porous Cu/Cu2O/CuO@CA. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2021, 9, 16450-8.

75. Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, D.; et al. Reasonable regulation of carbon/nitride ratio in carbon nitride for efficient photocatalytic reforming of biomass-derived feedstocks to lactic acid. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2021, 299, 120698.

76. Liu, Z.; Liu, K.; Sun, R.; Ma, J. Biorefinery-assisted ultra-high hydrogen evolution via metal-free black phosphorus sensitized carbon nitride photocatalysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137128.

77. Liu, K.; Ma, J.; Yang, X.; et al. Phosphorus/oxygen co-doping in hollow-tube-shaped carbon nitride for efficient simultaneous visible-light-driven water splitting and biorefinery. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 437, 135232.

78. Sun, S.; Zhang, J.; Hong, M.; Wen, J.; Ma, J.; Sun, R. Photocatalytic selective C–C bond cleavage of biomass-based monosaccharides and xylan to co-produce lactic acid and CO over an Fe-doped GaN catalyst. Ind. Crops. Prod. 2023, 204, 117361.

79. Sun, S.; Sun, S.; Liu, K.; Xiao, L.; Ma, J.; Sun, R. Construction of a metal-free photocatalyst via encapsulation of 1,2,3,5-tetrakis(carbazole-9-yl)-4,6-dicyanobenzene in a carboxymethylcellulose-based hydrogel for photocatalytic lactic acid production. Green. Chem. 2023, 25, 736-45.

80. Yang, X.; Liu, K.; Ma, J.; Sun, R. Carbon quantum dots anchored on 1,2,3,5-tetrakis(carbazole-9-yl)-4,6-dicyanobenzene for efficient selective photo splitting of biomass-derived sugars into lactic acid. Green. Chem. 2022, 24, 5894-903.

81. de Clippel, F.; Dusselier, M.; Van Rompaey, R.; et al. Fast and selective sugar conversion to alkyl lactate and lactic acid with bifunctional carbon-silica catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 10089-101.

82. Mateo, D.; Cerrillo, J. L.; Durini, S.; Gascon, J. Fundamentals and applications of photo-thermal catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 2173-210.

83. Hong, J.; Xu, C.; Deng, B.; et al. Photothermal chemistry based on solar energy: from synergistic effects to practical applications. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2103926.

84. Cheruvathoor, P. A.; Zoppellaro, G.; Konidakis, I.; et al. Fast and selective reduction of nitroarenes under visible light with an earth-abundant plasmonic photocatalyst. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2022, 17, 485-92.

85. Liu, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Xu, P.; et al. Solar thermal catalysis for sustainable and efficient polyester upcycling. Matter 2022, 5, 1305-17.

86. Xie, B.; Hu, D.; Kumar, P.; Ordomsky, V. V.; Khodakov, A. Y.; Amal, R. Heterogeneous catalysis via light-heat dual activation: a path to the breakthrough in C1 chemistry. Joule 2024, 8, 312-33.

87. Wang, H.; Cheng, X.; Li, Z.; Jing, L.; Hu, J. Photothermal catalytic enhancement of lignocellulosic biomass conversion: a more efficient way to produce high-value products and fuels. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 496, 153772.

88. Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Guo, L.; Chen, Z.; Li, C. Photothermally promoted cleavage of β-1,4-glycosidic bonds of cellulosic biomass on Ir/HY catalyst under mild conditions. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2018, 237, 660-4.

89. Liang, J.; Jiang, J.; Cai, T.; et al. Advances in selective conversion of carbohydrates into 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Green. Energy. Environ. 2024, 9, 1384-406.

90. Tsutsumi, K.; Kurata, N.; Takata, E.; Furuichi, K.; Nagano, M.; Tabata, K. Silicon semiconductor-assisted Brønsted acid-catalyzed dehydration: highly selective synthesis of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from fructose under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2014, 147, 1009-14.

91. Han, P.; Tana, T.; Sarina, S.; et al. Plasmonic silver nanoparticles promoted sugar conversion to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural over catalysts of immobilised metal ions. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2021, 296, 120340.

92. Tana, T.; Han, P.; Brock, A. J.; et al. Photocatalytic conversion of sugars to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural using aluminium(III) and fulvic acid. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4609.

93. Shi, Y.; Tana, T.; Yang, W.; et al. High-efficiency solar transformation of sugars via a heterogenous gallium(III) catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202409456.

94. Wang, A.; Berton, P.; Zhao, H.; Bryant, S. L.; Kibria, M. G.; Hu, J. Plasmon-enhanced 5-hydroxymethylfurfural production from the photothermal conversion of cellulose in a biphasic medium. ACS. Sustainable. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 16115-22.

95. Ye, X.; Zhong, M.; Cao, Z.; et al. Plasmon resonance enhanced palygorskite-based composite toward the photocatalytic reformation of cellulose biomass under full spectrum. Appl. Clay. Sci. 2023, 231, 106755.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].