Polar-group functionalized polyetherimide separator with accelerated Li-ion transport for stable lithium metal batteries

Abstract

Research on functional separators is crucial for the performance of batteries owing to the inability of commercial polyolefin separators to suppress dendrites growth in lithium metal batteries, resulting in poor performance and safety hazards. Herein, we report polar groups of terminal amino and amide functionalized polyetherimide separators [ethylenediamine grafting polyetherimide (PEI-EDA)] with uniformly connected pore structures. The PEI-EDA separator displays excellent thermal stability, electrolyte affinity and ion transport ability with an ionic conductivity of 1.96 mS·cm-1 and a Li+ transference number of 0.74. Notably, the lone-pair electrons in nitrogen atoms of the −NH2 and −CONH− groups have interaction with Li+, and the active hydrogens on them have the electrostatic interaction with PF6-, which achieves the desolvation of Li+, and improves ion transport rate and uniform lithium-ion flux, synergistically inducing homogeneous deposition of Li+, suppressing the growth of dendritic lithium and forming a stable fluorine-rich solid interphase layer and uniform cathode interphase layer. Furthermore, the data from online electrochemical mass spectroscopy (OLEMS) show that the gas production of a battery with a PEI-EDA separator is significantly reduced during the cycling process, which effectively improves the battery safety. Uniform and dense lithium deposition not only prolongs the cycle-life of Li||Cu and Li||Li cells but also enhances the rate capability and cycling stability of Li||LiFePO4 batteries even under high cathode loading and extreme temperature conditions. Moreover, the Li||LiFePO4 pouch battery displays stable cycling performance and benign safety under the folding state. This suggests the PEI-EDA separator has a promising application prospect in the next-generation secure dendrite-free metal batteries.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Lithium energy storage devices have been widely applied in portable electronic equipment, electric automobiles, wearable electronics,

As one of the most essential components of LMBs, separators act as the physical barrier, preventing electrode contact and providing porous channels for ion transport[19-21]. As commercially available separators, polyolefin separators are extensively used in lithium-ion batteries owing to their stability and excellent mechanical strength. However, because of their hydrophobic nature and low porosity, there exist high energy barriers for the entry and passage of Li+. Moreover, the slit-shaped pore structure leads to anisotropic mechanical properties[22], which are unfavorable to stable lithium plating/stripping. Therefore, improving the performance of the separator to prevent dendrites and increase ion transport rate is regarded as a promising method for increasing the electrochemical performance of batteries. In the past decade or more, many research works have focused on modifying polyolefin-based separators or designing new separators beyond polyolefin[23-25]. Guo et al. designed a modified polyacrylonitrile separator with graphene oxide by regulating the interfacial groups, and found that increasing the amount and types of oxygen-containing polar groups can boost the number of active sites for bonding and transferring sodium ions and accelerate the transmission of Na+[26].

The porous structure of the separators affects ion transport and the interface of the batteries. Generally, the high porosity of separators can facilitate ion transport[27,28], but having too large pores can give rise to some problems, such as self-discharge, open circuit voltage drops and the growth of lithium dendrites along the pores[29,30]. Chemical modification and introducing polar functional groups are effective ways to adjust the pore structure and improve the separator performance. Recently, polyetherimides (PEIs) with attractive characteristics such as good chemical stability, high thermal stability, excellent insulation properties and good electrolyte wettability have been used as separators[31,32]. Additionally, PEIs are easy to process and modify, and the C–N bond of the cyclic imide can be opened in special circumstances[33,34], while exposing more polar groups. Notably, the chemical modification method can not only regulate the outer surface property of PEIs without changing the structural stability, but also improve the inherent properties. Some studies have shown that the nitrogen atoms in the amino or amide groups can reduce the binding energy of anion and cation, promote ion dissociation, and increase the free ion concentration[35,36], which will improve the Li+ transfer kinetics and enhance the battery performance.

Herein, an ethylenediamine (EDA) grafting PEI [ethylenediamine grafting polyetherimide (PEI-EDA)] separator with spongy-like porous structure was fabricated through phase-inversion method. The PEI-EDA separator presents excellent flame retardancy, high ionic conductivity, superior lithium ion transference number, and exceptional electrochemical performance. Additional polar functional groups on PEI-EDA separators improve the transport dynamics of lithium ions. When combined with the evenly connected pore structures, they can efficiently accelerate the transport of Li+, induce stable plating/stripping, prevent dendritic Li growth, and form a homogeneous interface. Therefore, the Li||Li cells show a longer cycle-life and the Li||Cu cells get a higher coulombic efficiency even without electrolyte additives. Through the generation of fast ion transport and fine interface layers, the cells with PEI-EDA separators exhibit greatly improved cycling stability and high-rate capability.

EXPERIMENTAL

PEI (ULTEM 1000) was provided by SABIC Innovative Plastic. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, K88-96, Mw = 1,300,000) and Lithium bis (oxalate) borate (LiBOB, ≥) were purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co. Analytical-grade N, N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc), methanol and EDA were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Propylene carbonate, diethyl carbonate and liquid electrolyte consisting of 1 M LiPF6 dissolved in ethylene carbonate (EC): dimethyl carbonate (DMC): ethylmethyl carbonate (EMC) = 1:1:1 (vol%) were purchased from Dodochem, Suzhou, China. A commercial 25 μm polypropylene (PP) separator was provided by Guangdong Canrd New Energy Technology Co Ltd.

The PEI separator was prepared by phase inversion method. First, the 1.12 g PEIs and 0.84 g PVP were dissolved in DMAc at 70 °C to form a uniform solution. After standing for 12 h, the mixture was cast evenly onto a clean glass plate, soaked in water vapor, and then immersed in deionized water. The obtained PEI separator was dried at room temperature. Second, the PEI separator was immersed in a methanol solution containing 5% EDA for 10 h. After being grafted by EDA, the separator was used distilled water to wash 3 times. Third, the PEI-EDA separator was dried and preserved in a 60 °C oven for 6 h before use.

The cell assembly, electrochemical measurement and characterizations were introduced in Supplementary Materials in detail.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The PEI and PEI-EDA porous separators were prepared by phase inversion method [Figure 1A], which is simple and can be used to prepare the isotropic separators on a large scale. Meanwhile, the PEI-EDA separator can be prepared on a large area and rolled into rolls according to the size of the coated glass plate [Figure 1B]. By optimizing and regulating the content of pore-forming agents [Supplementary Figure 1], both the PEI and PEI-EDA separators have interconnected sponge-like pore structures from the top-surface and cross-section scanning electron microscopy (SEM) morphology images [Figures 1C and Supplementary Figure 2], which proved the chemical grafting of EDA hardly breaks the original pore structure of PEI separators. This morphology of PEI-EDA separators will be favorable for Li+ transport and induce the homogeneous deposition of lithium ions owing to the uniformly distributed pores and good affinity with electrolytes[32]. However, the commercialized PP separator exhibits a typical slit-like pore structure through melt spinning and cold stretching [Supplementary Figure 3]. This will lead to low porosity and poor wettability of separators, and then causes poor compatibility with interfaces, restricted ion migration and inhomogeneous stripping/plating[37,38]. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were used to characterize the structure of PEI and PEI-EDA separators [Figure 1D]. The absorbance peaks at 3,070 and 2,969 cm-1 are ascribed to the stretching vibration of the unsaturated and saturated C−H bonds, respectively. The characteristic peaks of benzene rings and carbonyl bonds are represented by the absorption peaks at 2,000-1,550 cm-1. In addition, the absorptions at 1,276 and 1,102 cm-1 are attributed to the stretching vibration of

Figure 1. Preparation and physical characterization of separators. (A) Fabrication process of PEI-EDA separator; (B) Rolls of the PEI-EDA separator; (C) SEM morphology images of PEI-EDA separator; (D) FT-IR spectra of PEI and PEI-EDA separators; (E) Strain-stress behavior of the PEI and PEI-EDA separators; (F) Burning images; (G) Photos of separators after different temperature heat treatment for 30 min; (H) DSC analysis. PEI-EDA: Ethylenediamine grafting polyetherimide; PEI: polyetherimide; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; FT-IR: fourier transform infrared; DMAc: N, N-dimethylacetamide; PP: polypropylene.

The thermal stability and flame retardancy of the separator are essential to the safety performance of the batteries. During the burning tests, the PEI-EDA separator self-extinguished quickly, whereas the commercial PP and PEI separators burn out entirely [Figure 1F and Supplementary Videos]. The better flame retardancy of PEI-EDA separators may be due to the increase of nitrogen element content. As presented in Figure 1G, 3 separators had the same size at 25 °C, and after staying in a muffle furnace at 100 °C for half an hour, PEI and PEI-EDA separators had no obvious shrinkage, but the PP separator curls a little. Moreover, the PP separator showed significant shrinking when heating to 150 °C, and then it shrunk entirely at 180 °C. However, the PEI and PEI-EDA retained their initial size well, even when heated to

The porosity and electrolyte uptake of different separators were tested and calculated according to Supplementary Equations 1 and 2, and the results were shown in Figure 2A. The PEI-EDA separator can maintain shape integrity and does not dissolve when immersed in different electrolyte solvents, even for

Figure 2. Evaluation of physiochemical parameters for PP, PEI and PEI-EDA separators. (A) Porosity and electrolyte-uptake rate; (B) Contact angle; (C) LSV curves (inset: the magnified LSV curves); (D) EIS analysis (inset: the magnified EIS analysis); (E) Li+ ion transference number (inset: Nyquist plots before and after polarization); (F) Radar chart of key properties indicators. PEI-EDA: Ethylenediamine grafting polyetherimide; PEI: polyetherimide; PP: polypropylene; LSV: linear sweep voltammetry; EIS: electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) measurement is used to evaluate the electrochemical stability of separators. The initial decomposition voltage of PEI-EDA is up to 5.04 V, indicating its excellent oxidation stability [Figure 2C]. The ion conduction behaviors of three types of separators were investigated via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) with symmetric cells with stainless steel (SS||SS) plates as electrodes [Figure 2D], and the ionic conductivities and ion transference numbers of 3 separators were calculated according to Supplementary Equations 3 and 4, respectively. After being modified by EDA, the bulk resistance (Rb) of the SS||PEI-EDA||SS cell gradually decreases from 0.89 to 0.78 Ω, and the ion conductivity increases from 1.72 to 1.96 mS·cm-1, both exceeding that of PP (0.96 mS·cm-1). Furthermore, the lithium-ion transference numbers (

Li-stainless steel (Li||SS) cells were used to evaluate the deposition/stripping kinetics with different separators. Figure 3A showed the cyclic voltammetry (CV) profiles of Li||SS cells with three membranes in the voltage range from -0.2 to 2.5 V (vs. Li/Li+) at a scan rate of 0.5 mV·s-1. Three predominant redox peaks appeared close to 0 V, which could be attributed to Li+ plating and stripping processes on the stainless-steel electrode. Remarkably, at the turning point of the curve with a negative sweep, the lithium deposition overpotential of the Li||SS cells assembled with the PEI-EDA separator was 38.9 mV, which was smaller than with PP (56.6 mV) and PEI separators (61.4 mV). In the subsequent plating and stripping process, the SS||PEI-EDA||Li cell exhibited a higher peak current density of 1.15 mA·cm-2 compared with the SS||PEI||Li (0.36 mA·cm-2) and SS||PP||Li cells (0.61 mA·cm-2), which agreed with the improved Li+ conductivity and Li+ ion transference number when used with PEI-EDA separators. That showed that the PEI-EDA separator had a higher plating/stripping efficiency and remarkable reversibility. Furthermore, the Tafel curves in Figure 3B displayed the exchange current density of 0.065, 0.059 and 0.104 mA·cm-2 for PP, PEI and PEI-EDA, respectively, indicating that the PEI-EDA separator had increased Li+ transfer kinetics. Then, the activation energies were further calculated by plotting Arrhenius equation [Supplementary Equation 5] in Figure 3C. The PEI-EDA separator presented the lowest activation energy (Ea) of 3.20 kJ mol-1, meaning that it can reduce the energy barrier for Li+ and is favorable for Li+ transport.

Figure 3. Li+ transport of separators and interaction with electrolyte. (A) CV profiles of Li||SS cells with 3 separators; (B) Tafel curves of 3 separators; (C) Ea obtained from linear fitting with Arrhenius equation; (D) 31P NMR spectra and (E) 19F NMR spectra of electrolyte and different separators with electrolyte; (F) 7Li NMR spectra of electrolyte and PEI-EDA separator with electrolyte; (G) FT-IR spectra between 3,400-3,100 cm-2 of PEI-EDA separator with and without electrolytes; (H) Schematic representation of the Li+ transfer mechanism in the PEI-EDA separator. CV: Cyclic voltammetry; NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance; PEI-EDA: ethylenediamine grafting polyetherimide; FT-IR: fourier transform infrared; PP: polypropylene; PEI: polyetherimide.

In order to explain the active role of the polar groups of −NH2− and −CONH−, the 31P nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), 19F NMR and 7Li NMR spectra of the separators with electrolytes were tested and shown in Figure 3D-F. As shown in Figure 3D and E, there was a new split peak showing in 31P NMR and 19F NMR of PEI-EDA separators; however, this phenomenon was not observed in other separators. It suggested that PEI-EDA separators provided different environments and had a weak interaction with PF6-. The 7Li NMR spectrum was measured to investigate the interaction between PEI-EDA separators and Li+ [Figure 3F]; it could be found that the peak becomes wider and transforms from double peaks to multiple peaks. Additionally, the main peak at -0.19 ppm in the 7Li NMR spectrum shifts upfield compared to the pure electrolyte at -0.17 ppm. This result was attributed to the lone-pair electrons on nitrogen atoms from the groups of −NH2 and −CONH− of PEI-EDA separator grafted with EDA, which exhibited strong interaction with Li+. The high Li+ affinity of PEI-EDA separators could stimulate the high dissociation of lithium ions from their counterparts, thereby enhancing the mobility of lithium ions[41]. The ionic affinity of the PEI-EDA separator to LiPF6 was also examined by FT-IR spectra. A blue shift of −NH2 and −CONH− in PEI-EDA separators was observed [Figure 3G]. The effect of the −NH2 and −CONH− groups on the PEI-EDA separator for Li+ transport properties was further demonstrated in Figure 3H. The PEI-EDA separator contains uniformly distributed terminal amino groups (−NH2) and the exposed amide groups (−CONH−), which interact with Li+ and PF6-. These polar groups facilitate Li+ transport and promote uniform lithium-ion flux.

The Li||Li symmetric cells were assembled to demonstrate the effect of the separators with liquid electrolytes for the suppression of lithium dendrites. When the current density was 0.2 mA·cm-2, the polarization voltages of the PP, PEI and PEI-EDA separators were 34.3, 31.4 and 27.6 mV after cycling 200 h [Figure 4A], respectively. As the cycle time increased to 1,800 h, the polarization voltage of PP, PEI and PEI-EDA separators increased to 51.9, 44.0 and 36.3 mV, respectively. It is worth noting that the PEI-EDA separator has superior performance with the smallest polarization compared with PP and PEI separators. Under the condition of low current density, a PEI separator had a slightly smaller polarization than a PP separator owing to its connected and uniform pores. When the current density rose to 1 mA·cm-2

Figure 4. Performance of the Li||Li and Li||Cu cells with PP, PEI and PEI-EDA separators. Constant current cycle curves of Li||Li symmetric cells at 0.2 mA·cm-2, 0.2 mAh·cm-2 (A), 1 mA·cm-2, 1 mAh·cm-2 (B), and at stepped-increased current densities from 0.5 to 5 mA·cm-2 (C); (D) EIS spectra of the Li||Li cells after 50 cycles; (E) Galvanostatic voltage profiles of Li deposition; (F) Performance of the Li||Cu cells; (G) Charge and discharge profiles of the Li||Cu cells; (H-J) SEM image of the Li-metal on Cu foil after five cycles at the density current of 0.5 mA·cm-2: (H) PP, (I) PEI, (J) PEI-EDA. PEI-EDA: Ethylenediamine grafting polyetherimide; PEI: polyetherimide; PP: polypropylene; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; EIS: electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

The Li||Cu half cells were assembled with 3 separators to test the efficiency of the deposition and stripping. As shown in Figures 4E, the nucleation potentials of PP, PEI and PEI-EDA separators were 74.4, 230.9 and 33.4 mV, respectively, suggesting that the energy barrier for Li+ deposition with PEI-EDA was lower than that of PP and PEI separators. In addition, the coulombic efficiency of Li||PEI-EDA||Cu cells remained around 81.0% after 100 cycles, which was significantly higher than the cells with the other 2 separators [Figure 4F and G]. After the Li||Cu half cells cycling at 0.5 mA·cm-2 (0.5 mAh·cm-2) for 5 cycles, the lithium metal on Cu foil with the PEI-EDA separator exhibited relatively smooth and regulated lithium dendrites growth [Figure 4H-J]; meanwhile, the surface morphology of the lithium metal with the PP and PEI separators displayed rough and filamentary lithium dendrites growth. Although the PEI separator had uniform pores, its large pore size made it easy for lithium dendrites to grow along the pores. However, the PEI-EDA separator had additional groups of −NH2 and −CONH− that can interact with Li+ and facilitate Li+ transfer. Moreover, the uniform and interconnected pores of PEI-EDA separators help promote uniform lithium-ion flux and induce stable plating/stripping. The synergistic effects of these factors efficiently inhibit the growth of lithium dendrites.

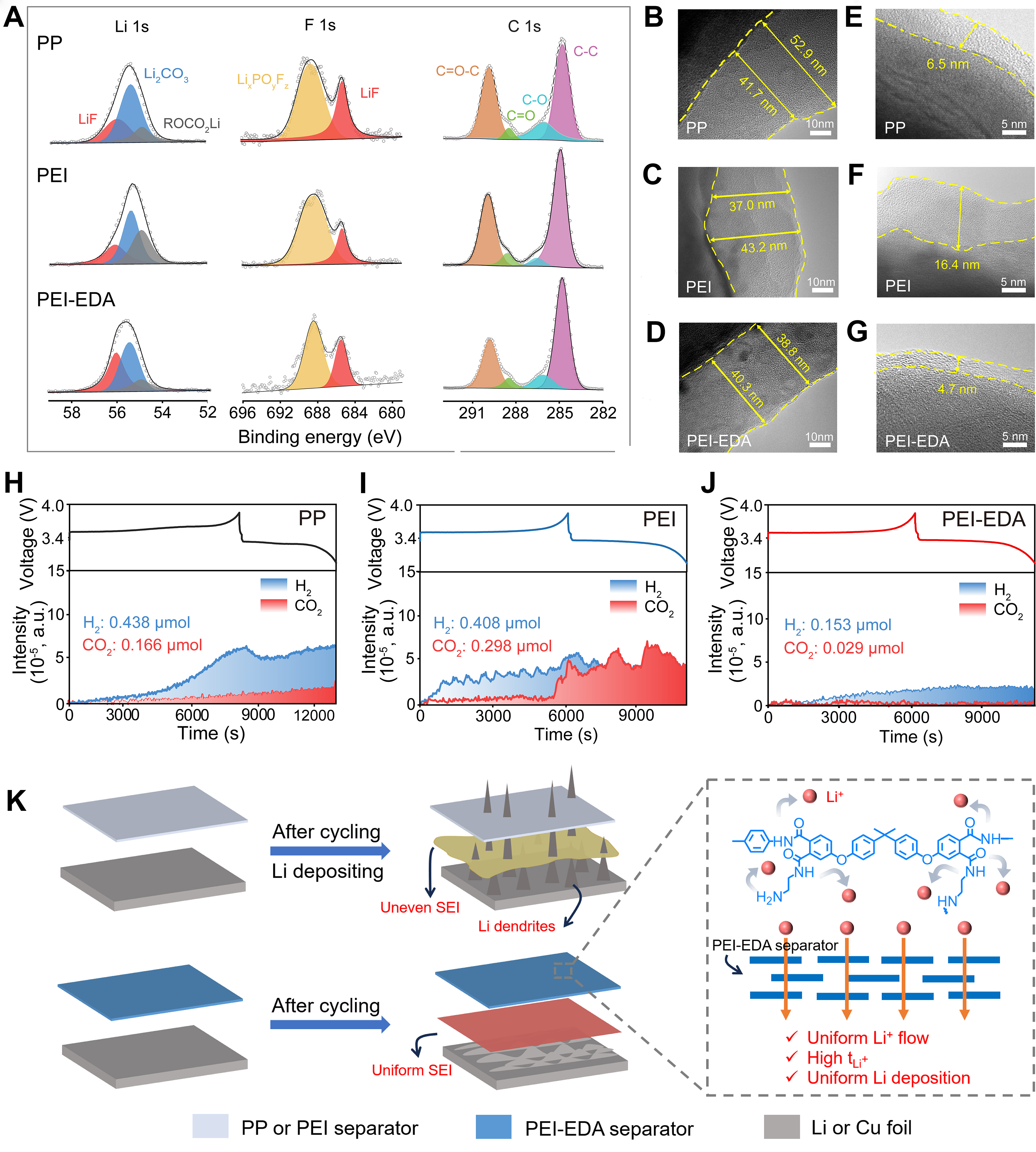

To further reveal the chemical composition of SEI films of the Li||Cu half cells assembled with 3 separators, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed [Figure 5A]. The SEI on Cu foil substrates with 3 separators is mainly composed of LiF, Li2CO3, ROCO2Li, and LixPOyFz. Specifically, in the C 1s spectra, the peaks of C=O–C, C=O, C–O and C–C derive from the decomposition of the liquid electrolyte. The F 1s spectra exhibited 2 peaks of LiF and LixPOyFz species, located at 684.8 and 688.6 eV, respectively[44]. The Li 1s spectra displayed 3 peaks belonging to the LiF, Li2CO3 and ROCO2Li, and the LiF content of the PEI-EDA separator had a high percentage of 37.8% due to the interaction of the PEI-EDA separator with PF6-. In comparison, the percentages of LiF were only 21.8% and 27.7% when equipped with PP and PEI separators, respectively [Supplementary Figure 8]. It is generally believed that the higher the LiF content in the SEI film, the more significant the lithium dendrite suppression effect, and the longer the cycle life of symmetric batteries[45]. A transmission electron microscope (TEM) was employed to measure the characteristics of SEI on Cu foil and cathode electrolyte interphases (CEI) of LiFePO4 (LFP) cathodes during the cycle process with different separators. After five cycles at the current of 0.5 mA·cm-2, the SEI on Cu foil with the PEI-EDA separator was more uniform [Figure 5B-D]. On the side of the cathode [Figure 5E-G], after the first cycle, the CEI on the LFP cathode with PEI-EDA was thin and uniform, which is conducive to the Li+ transport.

Figure 5. Interfacial chemistry with different separators. (A) Compositions of the SEI on Cu foil substrates after five cycles at the current of 0.5 mAh·cm-2 and corresponding XPS patterns by Li 1s, F 1s and C 1s. TEM characterization of the SEI on Cu foil after five cycles at the current of 0.5 mAh·cm-2 with different separators: (B) PP, (C) PEI, (D) PEI-EDA. TEM characterization of the LFP cathode after one cycle with different separators: (E) PP, (F) PEI, (G) PEI-EDA. OLEMS of Li|| LFP cells with different separators: (H) PP, (I) PEI, (J) PEI-EDA. (K) Li stripping/plating behavior with PP, PEI and PEI-EDA separators. SEI: Solid electrolyte interphases; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy; PEI-EDA: ethylenediamine grafting polyetherimide; PEI: polyetherimide; PP: polypropylene; TEM: transmission electron microscope; OLEMS: online electrochemical mass spectroscopy; LFP: LiFePO4.

What is particularly noteworthy is the gassing problem for many carbonate electrolytes in LMBs. OLEMS was used to detect the components of gases produced in the 3 separators during the first charge and discharge process [Figure 5H-J]. The result demonstrated that the main gases produced from 3 cells with different separators were hydrogen (H2) and carbon dioxide (CO2). H2 mainly comes from the reaction of moisture water in salts with lithium metal, side reactions between binder PVDF and lithium metal, and so on[46,47]. The cell production of H2 with PP, PEI and PEI-EDA separators was 0.438, 0.408, and 0.153 μmol, respectively. CO2 mainly comes from the decomposition of EC in electrolytes[48]. It could be seen that PP and PEI separators had gas production of 0.166 and 0.298 μmol, much higher than that of a PEI-EDA separator (0.029 μmol). From these results, it is clear that using a PEI-EDA separator can reduce the production of gas effectively by generating a stable and unique interface layer during the cycle process. Thanks to the flame retardancy and low production of gas, the safety of LMBs will be enhanced.

Figure 5K shows the Li stripping/plating behavior on the Li anode or Cu foil systems with commercial PP, PEI and PEI-EDA separators. The low porosity and wide pore size distribution of a PP separator leads to the nonuniform concentrated lithium-ion flux and then induces unmanageable dendrite growth during Li plating process. When paired with the PEI separator, its large pore size can easily lead to the growth of lithium dendrites along the pores. However, when employing the PEI-EDA separator, because of the uniform and interconnected pores and the homogeneously extra distributed polar −NH2 and −CONH− groups, lithium-ion flux is uniformed and then the following electro-deposition is well regulated accordingly. Furthermore, the high

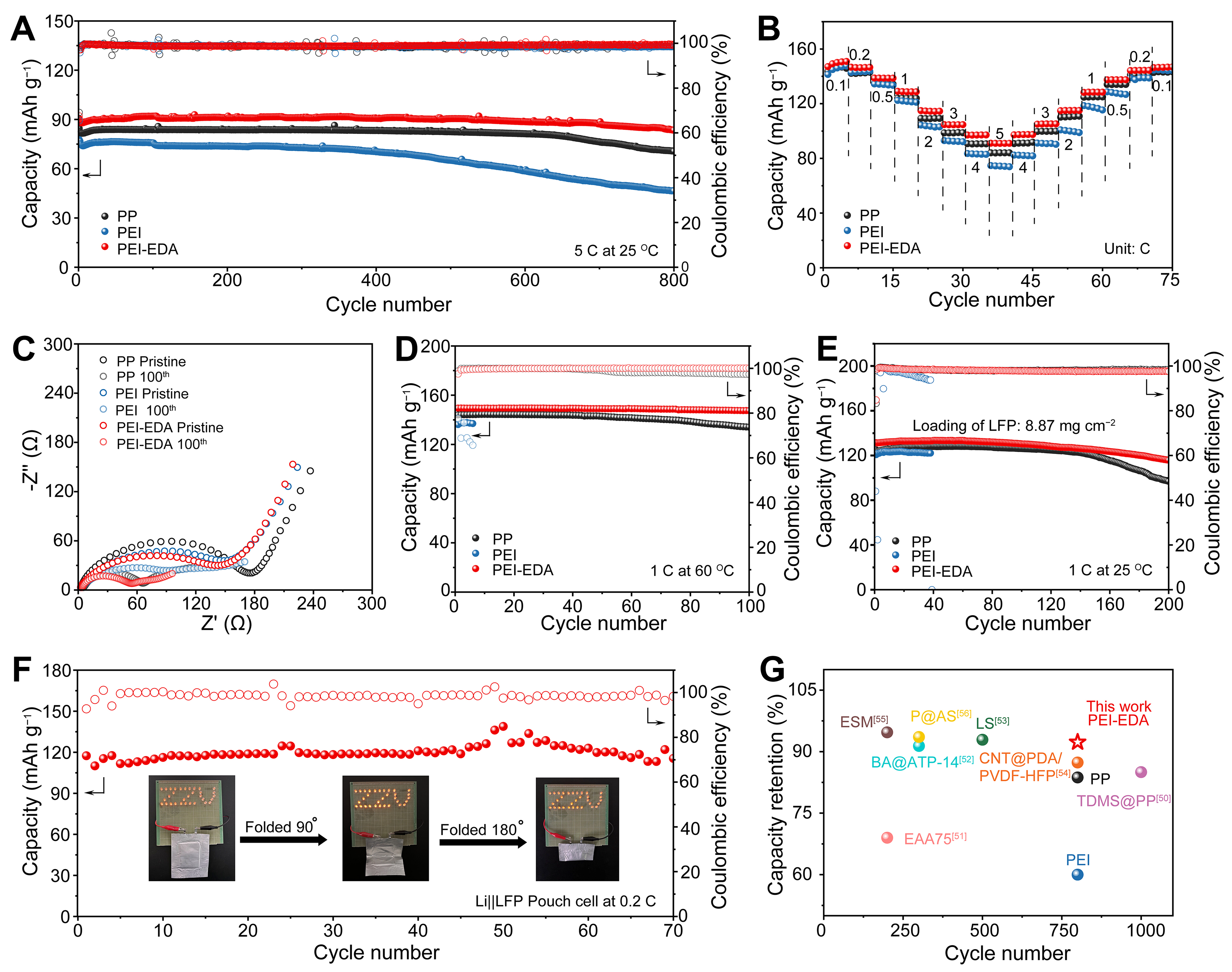

The advantage of the PEI-EDA separator had also been reflected by assembling into the Li||LFP cells. The CV profiles of Li||LFP cells with three different separators were measured and shown in Supplementary Figure 9. The CV profiles all display a pair of reversible oxidation-reduction peaks, and the Li||PEI-EDA||LFP cell has faster reaction kinetics with higher redox peaks. The cycling performance of the cells had been evaluated at a current density of 5 C (1 C = 170 mAh·g-1) [Figure 6A]. The initial capacity of cells with PP and PEI separators were 84.5 and 77.7 mAh·g-1, and the remaining capacities were 70.7 and 46.5 mAh·g-1 after 800 cycles with a capacity retention rate of 83.7% and 60.0%, respectively. However, the initial capacity of Li||PEI-EDA||LFP cell was 90.5 mAh·g-1, and the remaining capacity was 83.5 mAh·g-1 with a capacity retention rate of 92.3% after 800 cycles, which was obviously higher than the cells with other 2 separators. The detailed voltage-capacity curves to describe the capacity retention after 800 cycles at 5 C were shown in Supplementary Figure 10. Among all cells, the PEI-EDA separator displayed the highest capacity retention with a flat and stable voltage platform. Figure 6B showed the rate performance of 3 cells assembled by using 3 separators at different rates of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 C, respectively. The Li||PEI-EDA||LFP cell showed slightly higher capacities at different current densities, especially at high current densities. The corresponding galvanostatic charge and discharge curves at different rates further confirmed the better capacities of Li||PEI-EDA||LFP cells. Moreover, the Li||PEI-EDA||LFP cell exhibited significantly lower polarization voltage at each rate than PP and PEI separators [Supplementary Figure 11], indicating more efficient reaction kinetics and better rate performance. Furthermore, the Li||PEI-EDA||LFP cell had a smaller Ri compared with the other cells [Figure 6C].

Figure 6. Electrochemical performance of Li||LFP cells with PP, PEI and PEI-EDA separators. (A) Cycling performance at the current density of 5 C; (B) Rate performance; (C) EIS at different times; (D) Cycling performance at 60 °C; (E) Cycling performance of cells with high loading; (F) Cycling performance of Li||PEI-EDA||LFP pouch cell; (G) Comparison of electrochemical performances between this work and other reported separators. LFP: LiFePO4; PEI-EDA: ethylenediamine grafting polyetherimide; PEI: polyetherimide; PP: polypropylene; EIS: electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

Under extreme conditions, such as at high temperatures, lithium metal is more likely to react with electrolytes to produce inert lithium, ultimately leading to a sharp decline in battery performance. The cycling performance of three Li||LFP cells with different separators was tested at 60 °C. As shown in Figure 6D, the Li||PEI-EDA||LFP cell still circulated perfectly, and there was almost no capacity attenuation after 100 cycles. Meanwhile, the capacity retention of PP separator-based cells was 93.1%. However, the Li||PEI||LFP cell showed a short circuit after seven cycles owing to the intense growth of lithium dendrites under a higher temperature. Furthermore, under the high loading of 8.87 mg·cm-2, the Li||PEI-EDA||LFP cell was running well, and had an obviously higher capacity retention of 88.1% than a PP separator of 77.6% after 200 cycles [Figure 6E]. Not surprisingly, PEI separator-based cell short-circuited after 38 cycles.

In addition, the pouch cell with a size of 5.5 cm × 4.3 cm was assembled with a PEI-EDA separator, lithium metal and LFP, and it operated smoothly at a current density of 0.2 C [Figure 6F]. The Li||PEI-EDA||LFP pouch cell exhibited an initial discharge capacity of 25.6 mAh and a capacity retention of 98.3% after 70 cycles with an active material loading of 9.20 mg·cm-2. Even after folding 90° and 180°, the pouch cell could still light up the device. This meant that PEI-EDA separator-based cells had good safety and promising commercialization potential. Furthermore, PEI-EDA separators could be matched to many other high-voltage cathode materials (e.g., LiCoO2 and LiNiCoAlO2) and displayed commendable performance, as clearly shown in Supplementary Figure 12. All these results coincided with the conclusion from the Li||Li symmetric cells that the PEI-EDA was a preferable separator material to PP and PEI separators in LMB application. This was because the exposed groups of −NH2 and −CONH− after grafting give the separator a good ability to transport ions and inhibit lithium dendrites growth. Furthermore, the cycle numbers and capacity retention of cells using the PEI-EDA separator were compared with other reported separators

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, a PEI-EDA separator was prepared through phase-inversion and chemical grafting methods. By using this separator, we demonstrated a strategy to accelerate ion transport and regulate lithium dendrites growth for constructing stable LMBs. After grafting with EDA, the affinity with electrolyte, ionic conductivity (1.96 mS·cm-1), Li+ ion transference number (0.74), flame retardance and thermal stability of the separators were significantly enhanced. Moreover, the lone-pair electrons in the nitrogen from the groups of −NH2 and −CONH− on PEI-EDA separators interacted with Li+, facilitating rapid Li+ transfer, uniform lithium-ion flux, and stable Li+ plating/stripping to suppress lithium dendrites growth. The functional groups were H2-containing and had the electrostatic interaction with PF6-, realizing the formation of stable interphase fluorine-rich layers. During the cycling of Li||PEI-EDA||LFP cells, a stable interface layer could form to reduce gas production. Therefore, when using the PEI-EDA separator, the performances of both the Li||Li symmetric cell and Li||LFP cell were better than those of the PP and PEI separators. The Li||PEI-EDA||Li symmetric cells delivered a good cycling stability of over 300 h at a current density of 1 mA·cm-2 and a capacity of 1 mAh·cm-2. Uniform and dense lithium deposition not only provides the Li||Cu and Li||Li cells with long cycle life, but also improves the rate performance and cell lifespan. The Li||PEI-EDA||LFP cell exhibited superior rate performance and cycling stability, even with high cathode loading and without any electrolyte additives, and presented a capacity retention of 92.3 % after 800 cycles at 5 C. Furthermore, the Li||PEI-EDA||LFP pouch cells exhibited a capacity retention of 98.3% after 70 cycles at 0.2 C. Consequently, PEI-EDA separators have a promising application prospect that can be prepared on a large scale and provide remarkable performance for secure dendrite-free metal batteries.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Wrote the draft manuscript: Sun Y, Zhu H, Guo X

Revised and rewrote the manuscript: Zheng J, Yang M, Wang E, Feng X, Chen W

Availability of data and materials

Electrochemical measurement and cell assembly are available in the Supplementary Materials, and the data supporting the findings of this study are available within its Supplementary Materials.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22279121), the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (No. 222300420525), Key Research and Development Program of Henan Province (231111241400), Joint Fund of Scientific and Technological Research and Development Program of Henan Province (222301420009), China Scholarship Council (CSC202108410361) and the funding of Zhengzhou University.

Conflicts of interest

Chen W is the Guest Editor of the Special Issue “Electrochemical Energy Storage” and the Junior Editorial Board Member of Chemical Synthesis, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

2. Tian, Y.; Zeng, G.; Rutt, A.; et al. Promises and challenges of next-generation “beyond Li-ion” batteries for electric vehicles and grid decarbonization. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1623-69.

3. Bi, C. X.; Zhao, M.; Hou, L. P.; et al. Anode material options toward 500 Wh kg-1 lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2103910.

4. Chen, S.; Niu, C.; Lee, H.; et al. Critical parameters for evaluating coin cells and pouch cells of rechargeable Li-metal batteries. Joule 2019, 3, 1094-105.

5. Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Z. Towards practical lithium-metal anodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 3040-71.

6. Kim, K.; Kang, J.; Lee, H. Hybrid thermoelectrochemical and concentration cells for harvesting low-grade waste heat. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 131797.

7. Lin, D.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Z.; et al. Layered reduced graphene oxide with nanoscale interlayer gaps as a stable host for lithium metal anodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016, 11, 626-32.

8. Wu, C.; Huang, H.; Lu, W.; et al. Mg doped Li-LiB alloy with in situ formed lithiophilic LiB skeleton for lithium metal batteries. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1902643.

9. Li, W.; Guo, X.; Song, K.; et al. Binder-induced ultrathin SEI for defect-passivated hard carbon enables highly reversible sodium-ion storage. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2023, 13, 2300648.

10. Yan, C.; Cheng, X. B.; Yao, Y. X.; et al. An armored mixed conductor interphase on a dendrite-free lithium-metal anode. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1804461.

11. Zeng, Z.; Murugesan, V.; Han, K. S.; et al. Non-flammable electrolytes with high salt-to-solvent ratios for Li-ion and Li-metal batteries. Nat. Energy. 2018, 3, 674-81.

12. Wang, Y.; Dong, S.; Gao, Y.; et al. Difluoroester solvent toward fast-rate anion-intercalation lithium metal batteries under extreme conditions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5408.

13. Hao, Z.; Wang, C.; Wu, Y.; et al. Electronegative nanochannels accelerating lithium-ion transport for enabling highly stable and high‐rate lithium metal anodes. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2023, 13, 2204007.

14. Ji, Y.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, J.; et al. A single-layer piezoelectric composite separator for durable operation of Li metal anode at high rates. Energy. Environ. Mater. 2024, 7, e12510.

15. Sheng, L.; Xie, X.; Arbizzani, C.; et al. A tailored ceramic composite separator with electron-rich groups for high-performance lithium metal anode. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 657, 120644.

16. Guo, X.; Xie, Z.; Wang, R.; et al. Interface-compatible gel-polymer electrolyte enabled by NaF-solubility-regulation toward all-climate solid-state sodium batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202402245.

17. Xu, H.; Cao, G.; Shen, Y.; et al. Enabling argyrodite sulfides as superb solid-state electrolyte with remarkable interfacial stability against electrodes. Energy. Environ. Mater. 2022, 5, 852-64.

18. Zhu, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Tunneling interpenetrative lithium ion conduction channels in polymer-in-ceramic composite solid electrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 6591-603.

19. Feng, X.; Wang, M.; Zheng, J.; Ge, J.; Yang, M.; Chen, W. Facile preparation of higher conductivity porous polyimide-based separators by phase inversion and its overcharge-sensitive modification for lithium-ion batteries. Batteries. Supercaps. 2023, 6, e202300244.

20. Huang, X.; He, R.; Li, M.; Chee, M. O. L.; Dong, P.; Lu, J. Functionalized separator for next-generation batteries. Mater. Today. 2020, 41, 143-55.

21. Hao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Functional separators regulating ion transport enabled by metal-organic frameworks for dendrite-free lithium metal anodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2102938.

23. Li, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, F.; et al. Anionic metal-organic framework modified separator boosting efficient Li-ion transport. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138536.

24. Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Tian, T.; et al. Sustainable separators for high-performance lithium ion batteries enabled by chemical modifications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1902023.

25. Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X.; et al. An ultrathin nonporous polymer separator regulates Na transfer toward dendrite-free sodium storage batteries. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2203547.

26. Guo, X.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J. Understanding the accelerated sodium-ion-transport mechanism of an interfacial modified polyacrylonitrile separator. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2022, 126, 8238-47.

27. Li, C.; Liu, S.; Shi, C.; et al. Two-dimensional molecular brush-functionalized porous bilayer composite separators toward ultrastable high-current density lithium metal anodes. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1363.

28. Jung, A.; Lee, M. J.; Lee, S. W.; Cho, J.; Son, J. G.; Yeom, B. Phase separation-controlled assembly of hierarchically porous aramid nanofiber films for high-speed lithium-metal batteries. Small 2022, 18, e2205355.

29. Hu, W.; Fu, W.; Jhulki, S.; et al. Heat-resistant Al2O3 nanowire-polyetherimide separator for safer and faster lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 142, 112-20.

30. Ye, F.; Zhang, X.; Liao, K.; et al. A smart lithiophilic polymer filler in gel polymer electrolyte enables stable and dendrite-free Li metal anode. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020, 8, 9733-42.

31. Wang, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Stable sodium-metal batteries in carbonate electrolytes achieved by bifunctional, sustainable separators with tailored alignment. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2206367.

32. Hussain, A.; Mehmood, A.; Saleem, A.; et al. Polyetherimide membrane with tunable porous morphology for safe lithium metal-based batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 453, 139804.

33. Machatschek, R.; Heuchel, M.; Lendlein, A. Thin-layer studies on surface functionalization of polyetherimide: hydrolysis versus amidation. J. Mater. Res. 2022, 37, 67-76.

34. He, X.; Zhou, A.; Shi, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, W. Solvent resistant nanofiltration membranes using EDA-XDA co-crosslinked poly(ether imide). Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 206, 247-55.

35. Zhang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Song, Y.; et al. Tannic acid/polyethyleneimine-decorated polypropylene separators for Li-ion batteries and the role of the interfaces between separator and electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta. 2018, 275, 25-31.

36. Doyle, R. P.; Chen, X.; Macrae, M.; et al. Poly(ethylenimine)-based polymer blends as single-ion lithium conductors. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 3401-8.

37. Lee, J.; Park, H.; Hwang, J.; Noh, J.; Yu, C. Delocalized lithium ion flux by solid-state electrolyte composites coupled with 3D porous nanostructures for highly stable lithium metal batteries. ACS. Nano. 2023, 17, 16020-35.

38. Guo, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, L.; et al. Thermally conductive AlN-network shield for separators to achieve dendrite-free plating and fast Li-ion transport toward durable and high-rate lithium-metal anodes. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2200411.

39. Jiao, S.; Ren, X.; Cao, R.; et al. Stable cycling of high-voltage lithium metal batteries in ether electrolytes. Nat. Energy. 2018, 3, 739-46.

40. Shi, J.; Fang, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, B.; Zhu, L. Improved thermal and electrochemical performances of PMMA modified PE separator skeleton prepared via dopamine-initiated ATRP for lithium ion batteries. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 437, 160-8.

41. Zhang, H.; Sheng, L.; Bai, Y.; et al. Amino-functionalized Al2O3 particles coating separator with excellent lithium-ion transport properties for high-power density lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 1901545.

42. Cai, Q.; Wang, J.; Jiao, Y.; et al. All-graphitic multilaminate mesoporous membranes by interlayer-confined molecular assembly. Small 2021, 17, e2101173.

43. Wang, C.; Zhao, X.; Li, D.; Yan, C.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, L. Z. Anion-modulated ion conductor with chain conformational transformation for stabilizing interfacial phase of high-voltage lithium metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202317856.

44. Ha, H.; Kil, E.; Kwon, Y. H.; Kim, J. Y.; Lee, C. K.; Lee, S. UV-curable semi-interpenetrating polymer network-integrated, highly bendable plastic crystal composite electrolytes for shape-conformable all-solid-state lithium ion batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6491.

45. Yang, Y.; Yao, S.; Wu, Y.; et al. Hydrogen-bonded organic framework as superior separator with high lithium affinity C═N bond for low N/P ratio lithium metal batteries. Nano. Lett. 2023, 23, 5061-9.

46. Liu, P.; Yang, L.; Xiao, B.; et al. Revealing lithium battery gas generation for safer practical applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2208586.

47. Jin, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wei, D.; et al. Detection of micro-scale Li dendrite via H2 gas capture for early safety warning. Joule 2020, 4, 1714-29.

48. Lu, Z.; Yang, H.; Guo, Y.; et al. Electrolyte sieving chemistry in suppressing gas evolution of sodium-metal batteries. Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202206340.

49. Chazalviel, J. Electrochemical aspects of the generation of ramified metallic electrodeposits. Phys. Rev. A. 1990, 42, 7355-67.

50. Ren, W.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, W.; et al. Dendrite-free lithium metal battery enabled by dendritic mesoporous silica coated separator. Adv. Funct. Materials. 2023, 33, 2301586.

51. Chen, Y.; Mickel, P.; Pei, H.; et al. Bioinspired separator with ion-selective nanochannels for lithium metal batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 18333-42.

52. Liao, C.; Mu, X.; Han, L.; et al. A flame-retardant, high ionic-conductivity and eco-friendly separator prepared by papermaking method for high-performance and superior safety lithium-ion batteries. Energy. Stor. Mater. 2022, 48, 123-32.

53. Zuo, L.; Ma, Q.; Xiao, P.; et al. Upgrading the separators integrated with desolvation and selective deposition toward the stable lithium metal batteries. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2311529.

54. Yuan, B.; Feng, Y.; Qiu, X.; et al. A safe separator with heat-dispersing channels for high-rate lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2308929.

55. Ma, L.; Chen, R.; Hu, Y.; et al. Nanoporous and lyophilic battery separator from regenerated eggshell membrane with effective suppression of dendritic lithium growth. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2018, 14, 258-66.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].