Selection of five different types of animal models of Alzheimer’s disease: based on pathological similarity and research objectives

Abstract

Since the first report of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in 1906, scientists have made remarkable progress in elucidating its molecular mechanisms, pathogenic processes, and core neuropathological features. However, effective therapeutic strategies for AD remain elusive, and the disease is still fundamentally incurable. The use of animal models constitutes a critical step in investigating pathological mechanisms and conducting preclinical experiments. With advances in transgenic technology, a variety of mouse models have been developed to replicate the pathological changes, as well as cognitive and motor impairments, observed in AD patients. These models have played a pivotal role in studying the pathogenesis of AD and screening potential therapeutic approaches. For example, the Tg2576 mouse model can simulate AD-related pathological alterations, including β-amyloid (Aβ) plaque deposition, neuroinflammation, and cognitive impairment. Nevertheless, mouse models have limitations in mimicking the complex pathology and clinical manifestations of human AD. In contrast, some medium- to large-sized animals in nature, such as canines and non-human primates (NHPs), can spontaneously develop AD-like pathological changes. For instance, NHPs exhibit high similarity to humans in terms of brain structure and function, and their spontaneous AD-like pathological changes provide a more human-relevant model for investigating AD pathogenesis and drug screening. This article elaborates on the pathological characteristics, clinical manifestations, advantages, and disadvantages of five distinct animal models (mouse, cat, dog, sheep and NHPs) in experimental research, thereby providing a reference for model selection in AD studies.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

According to Gustavsson et al., approximately 416.4 million people were on the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) continuum as of 2022[1]. This includes 32.3 million people with AD, 69 million in the prodromal stage, and 315.2 million in the preclinical stage. AD is emerging as one of the most expensive, deadly, and burdensome diseases. Approximately 5% of AD cases are early-onset familial AD (EOFAD). These patients develop pathological changes and cognitive dysfunction before the age of 65, typically due to mutations in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene, presenilin 1 (PSEN1), or presenilin 2 (PSEN2) genes. However, the majority of AD patients develop sporadic AD (SAD) later in life, termed late-onset sporadic AD (LOSAD)[2-4]. In terms of pathophysiology, the primary feature of AD is the accumulation of β-amyloid

Neuropathology of AD

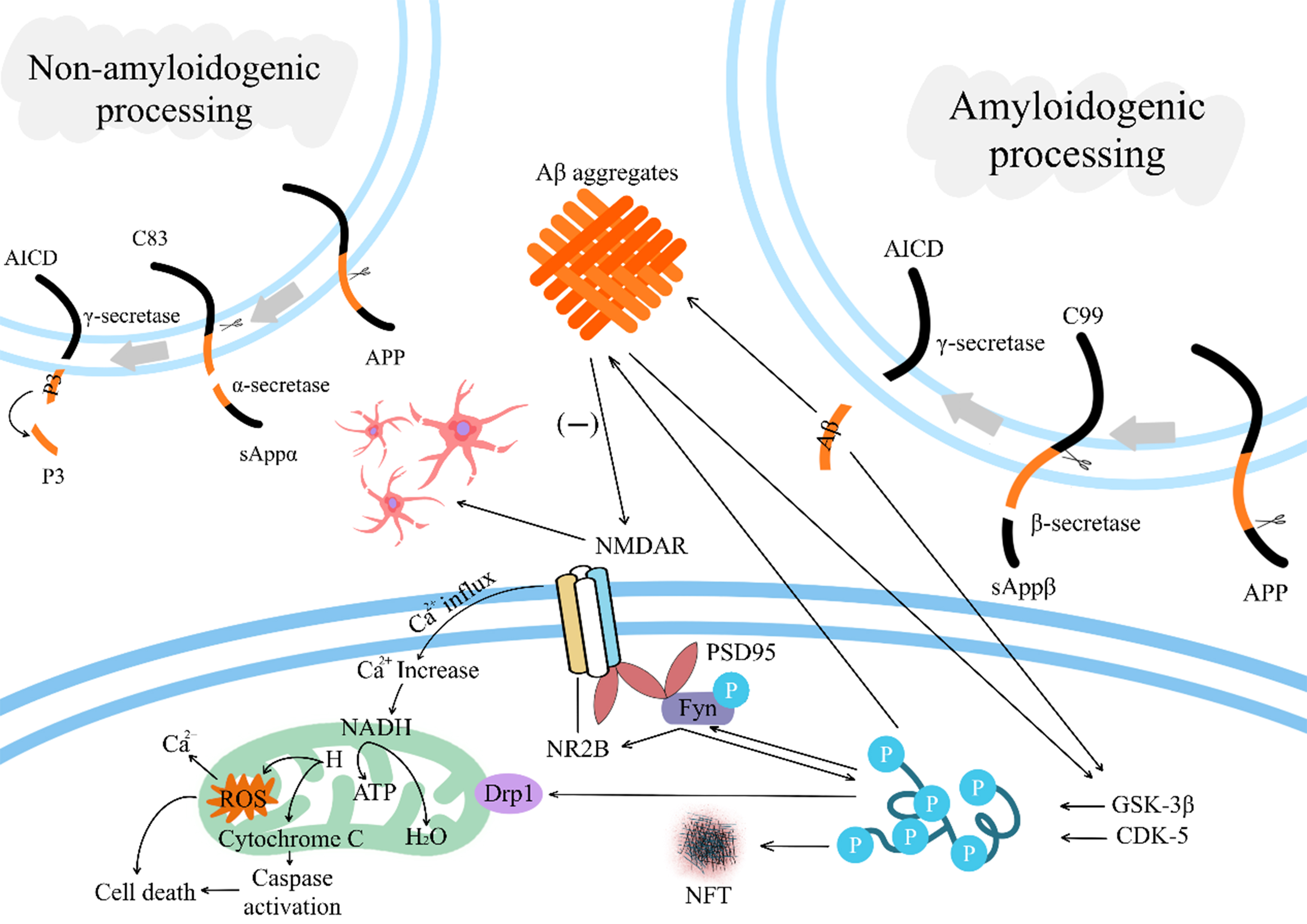

Aβ is a cleavage product of the glycoprotein APP, which is commonly found in the brain as part of a biological signal transduction process[8]. APP is a transmembrane protein that can be digested by α, β, and γ enzymes to produce Aβ peptides of different lengths, of which the Aβ of amyloid plaques formed in AD is mainly Aβ42[9,10]. Research evidence suggests that soluble Aβ oligomers (AβOs) are major neurotoxic substances and are responsible for progressive neurodegeneration in AD patients[11,12]. Soluble AβOs can rapidly downregulate the membrane expression of postsynaptic spinal proteins, including N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-type glutamate and Ephrin receptor B2 (EphB2) receptors, thereby blocking hippocampal long-term potentiation and promoting long-term synaptic depression[12,13]. Dysregulation of

In-depth studies reveal that exclusive focus on Aβ/tau neurotoxicity, neglecting their interactions, yields no therapeutic efficacy[22-24]. There are multiple phosphorylation sites on tau, which are phosphorylated by a variety of enzymes, including a-kinase, c-kinase, cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK-5), and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β)[25]. Aggregated Aβ can accelerate the hyperphosphorylation of tau by mediating the activation of CDK-5 and GSK-3β[26,27]. Also, Aβ toxicity is associated with tau. Phosphorylated tau interacts with Fyn kinase, and activated Fyn forms N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)-postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95)-Fyn complexes (NMDARs) with NR2B. Activation of NMDARs increases Ca2+ influx into the cell, leading to dysfunctional mitochondrial dynamics and ultimately, the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and apoptosis[28-30] [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Deposition of Aβ and the process of interaction with p-tau. In the non-amyloidogenic processing pathway, APP is cleaved by α-secretase and γ-secretase, ultimately generating non-toxic soluble fragments (such as sAPPα and P3); In the amyloidogenic processing pathway, APP is cleaved by β-secretase and processed by γ-secretase to produce Aβ peptides. Aβ activates CDK-5 and GSK-3β, accelerating tau hyperphosphorylation. Phosphorylated tau activates Fyn kinase, which assembles with NR2B to form NMDAR receptors. Their activation induces calcium influx, disrupts mitochondrial balance, generates excessive ROS, and ultimately triggers cell apoptosis; Aβ leads to the sustained loss of dendritic spines and glutamatergic synapses by reducing the activation of NMDARs or enhancing the activation of NMDAR-dependent calcineurin. Aβ: β-amyloid; p-tau: hyperphosphorylated tau; APP: amyloid precursor protein; sAPPα: secreted amyloid precursor protein alpha; P3: amyloid β-peptide 17-40/42; CDK-5: cyclin-dependent kinase 5; GSK-3β: glycogen synthase kinase-3β; NR2B: glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 2B; NMDAR: N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; ROS: reactive oxygen species; AICD: amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain; PSD95: postsynaptic density protein 95; NADH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced form; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; NFT: neurofibrillary tangle.

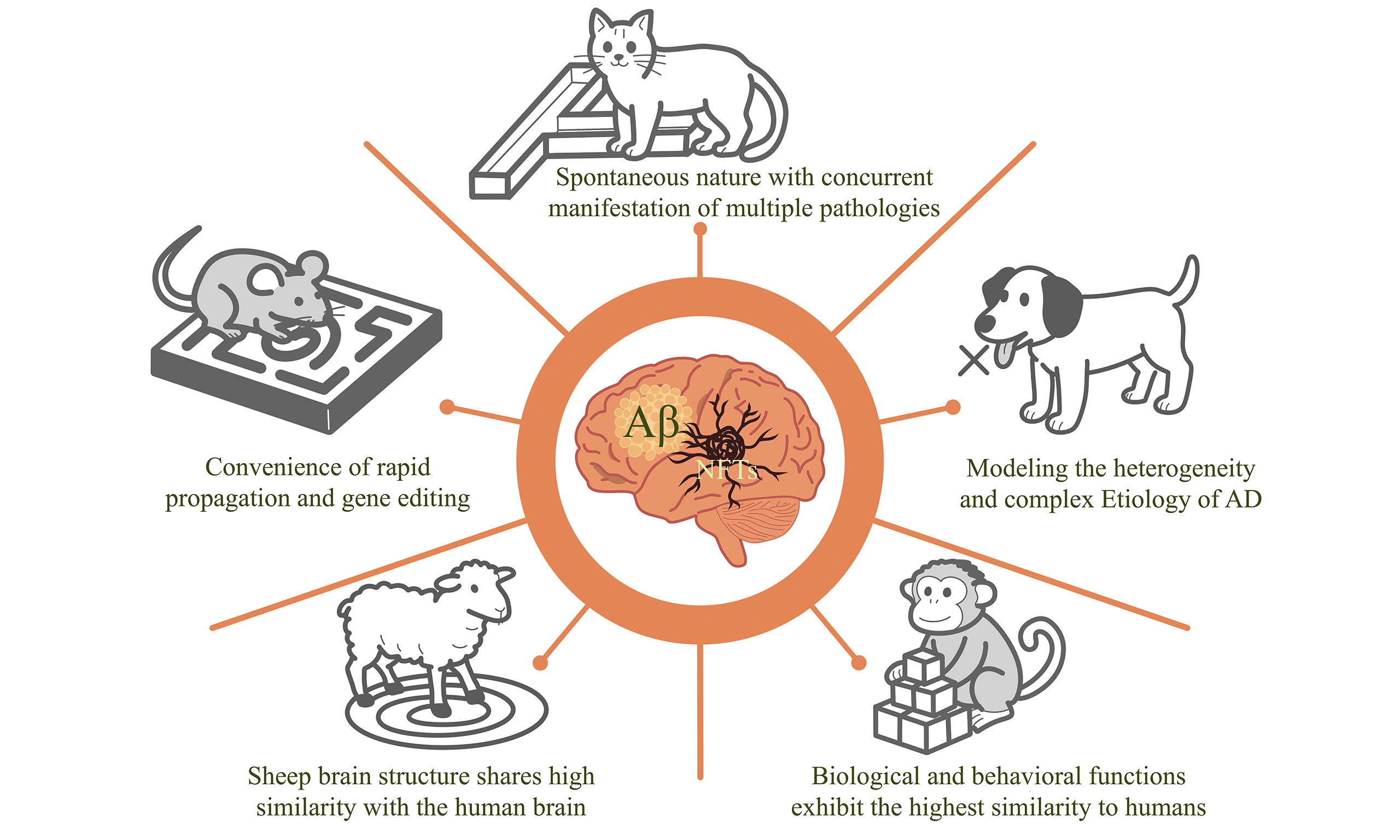

Animal models of AD have a long history, including rhesus monkeys, crab-eating macaques, marmosets, sheep, mini-pigs, dogs, cats, rats, mice, zebrafish, Drosophila, roundworms, and others. These animal models are classified into higher mammals, rodents, birds, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates, providing researchers with diverse perspectives for studies. As a typical animal model, mouse models have made significant contributions to research on the molecular mechanisms and pathological characteristics of AD pathogenesis. However, since AD is associated with multiple factors (such as age and environment), these models cannot fully capture the complexity of AD. Cat and dog models can spontaneously develop AD-like pathology, and their age of onset and living environment are similar to those of humans, enabling them to better simulate the pathological and clinical symptoms of AD. Nevertheless, current research on these two models remains limited. Sheep and non-human primate (NHP) models can also develop AD spontaneously and are more similar to humans in anatomy and physiology, but they have high rearing costs and are difficult to implement in a quantifiable manner. This article introduces the pathological and behavioral characteristics of five different types of animal models (mouse, cat, dog, sheep and NHPs), providing references for researchers in selecting models for studying AD pathological mechanisms, model development, and drug clinical trials.

MOUSE MODELS

To date, researchers have designed many mouse models for AD research, all of which share similar pathology and symptoms to human AD. Model studies have supported the application of biomarkers such as Aβ42/40 and p-tau in the early diagnosis of AD, and verified the role of controlling cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive training in delaying the progression of AD. However, many mouse models can only simulate partial pathological features of AD. For example, some models can only exhibit Aβ plaques but fail to form NFTs. Environmental factors may play an important role in the occurrence and development of AD, such as lifestyle, diet, and infection[31]. Mouse models also have significant differences from humans in terms of living environment. New AD risk factors and molecular pathways related to disease pathogenesis are continuously revealed with next-generation high-throughput genomic approaches to AD. Genome editing tools, such as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), can efficiently generate specific gene mutations in rats and design animal models that match AD’s characteristics. Compared with traditional transgenic methods, CRISPR-engineered models exhibit significant advantages in terms of precision and efficiency. They allow for precise editing of specific genes, possess extremely high flexibility and versatility, and can be used for various genetic manipulations as well as the construction of complex genetic backgrounds. However, CRISPR technology also faces operational challenges, including relatively complex procedures, high costs, and risks associated with off-target effects.

Transgenic (Tg) models

Among the transgenic mouse models in the past, there are some more complete transgenic mouse models of AD pathology. The triple-transgenic mouse model of AD (3xTg-AD) was developed in 2003 by co-microinjecting two separate transgenes, encoding human APPSwe and human tauP301L, into single-cell embryos of pure mutant PS1M146V knock-in (KI) mice[32]. In an assay of soluble and insoluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 in the hippocampal and cortical tissues of 3xTg-AD mice (with soluble and insoluble corresponding to recently produced Aβ and Aβ still present in plaques, respectively), both forms of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in both tissues increased with age, remaining at lower levels at 4 and 12 months and rising significantly by 18 months. In line with this, Aβ plaques also increased with age, with a significant increase in plaque volume at 18 months. Interestingly, the pathologic features were more pronounced in female than male mice. The p-tau pathology was also observed in 3xTg-AD mice, and strong signals of phosphorylated tau [AT8+ (antibody against paired helical filament tau phosphorylated at the Serine 202 and Threonine 205 sites) and p-tau217+] were present in the brains of 3xTg-AD mice at 18 months of age. NFTs were only found in the hippocampus of 18-month-old female 3xTg-AD mice, and there were no NFTs in males or any other brain regions[33]. Oakley et al. (2006) developed a transgenic mouse model co-expressing five FAD mutations (5XFAD mice)[34]. Immunofluorescence analysis of brain tissues at various ages revealed progressive age-dependent accumulation of Aβ. At 4 months of age, plaques appeared as compact circular structures, while with advancing age (12-18 months), these deposits evolved into irregular morphologies with diffuse halos in subcortical regions, the CA1 hippocampal subfield, and cortical areas - a pattern mirroring those observed in human AD’s pathology[35]. The Tg2576 mouse model, expressing the human APP isoform harboring the Swedish double mutation (APPswe), represents one of the most extensively studied disease models for amyloid pathology and cognitive deficits[36]. Elevated Aβ levels are detected starting from early ages (< 5 months old), with amyloid plaque deposition initiating in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex at 9-12 months of age[37-39]. These plaques progressively accumulate thereafter, reaching concentrations comparable to those observed in AD brains. In Tg2576 mice, Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) and p-tau show age-dependent increases starting at 12 and 18 months, respectively, escalating with age. Notably, p-tau accumulates prominently in lipid rafts of incredibly aged Tg2576 brains[40].

Thy1-ApoE4/C/EBPβ mice

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine-activated transcription factor that enhances δ-secretase (cleaves APP and tau) and selectively promotes ApoE4 expression in human neurons[41,42]. Overexpression of C/EBPβ has been shown to accelerate AD pathology in 3xTg and 5xFAD mouse models[43]. Based on this understanding, researchers bred Thy1-ApoE4/C/EBPβ double transgenic mice. The model was able to show progressive learning and memory deficits, and in Morris Water Maze (MWM) experiments, mice showed no deficits at 2 months of age, cognitive deficits at 6 months, which worsened by 12 months, while their operant function remained consistently normal. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging showed that Aβ PET signals were significantly elevated in this model mouse at 6 months and further enhanced at 12 months. The size of Aβ aggregates also increased with age, and there were extensive Aβ deposits in the forebrain, with the cortex being the most abundant. In an examination of tau NFT pathology, Thy1-ApoE4/C/EBPB mice were found to have both total Tau and p-Tau increased in an age-dependent manner and to share a similar protofibrillar structure to human tau aggregates, which exhibit infectivity and neurotoxicity.

Streptozotocin intracerebroventricular (STZ-icv) mice and STZ-icv rats

AD pathology can also arise when there is insulin resistance or glucose deficiency in the brain[44,45]. Streptozotocin (STZ) is a cytotoxic compound that can lead to insulin resistance in the brain by inhibiting the Akt/protein kinase B pathway (Akt/PKB) and insulin receptor signaling pathways, as well as activating glycogen synthase-3β, which promotes Aβ accumulation and Tau hyperphosphorylation[46]. Scientists established a streptozotocin intracerebroventricular (STZ-icv) mouse model by injecting a low dose of STZ[47]. In the STZ-icv mouse model, memory impairment showed a clear dose-dependent relationship and was most pronounced at the highest STZ-icv dose. Cognitive function declined sharply within the first month post-injection, showed some improvement later, but ultimately continued a gradual decline. The number of Aβ42 in the brains of STZ-icv mice was age-dependent and tended to spread (from the cortex to the hippocampus) compared to controls. P-tau was similarly age-dependent, with AT8+ signaling particularly strong during months 6 and 9 after STZ injection.

STZ-icv rats can exhibit most of the pathological features of AD and are regarded as a non-transgenic preclinical model of AD[48,49]. Similarly, they also exhibit a distinct dose dependency. Aβ plaques can first be detected in rats approximately 3 months old at a dose of 40 mg/kg[50], while at a lower injection dose of

KI mouse models of AD

To circumvent the limitations of transgenic technology, such as overexpression artifacts, random genetic integration, and ectopic spatiotemporal expression[52], scientists have developed next-generation mouse models using the KI approach. These include APP, Tau, ApoE, and other KI models.

Xia et al. homologously recombined three pathogenic coding mutations (Swedish, Arctic, and Austrian) into the mouse genome, generating a novel mouse model, APPSAA. Analysis of the spatial distribution of Aβ plaques across the whole brain revealed that Aβ plaques in homozygous mice increased with age at 4 and 8 months, whereas no Aβ plaques were detected in heterozygous APPSAA mice or wild-type mice. Compared with commonly used transgenic models (e.g., APP and 5XFAD), the density of Aβ plaques in homozygous APPSAA mice was comparable, which also induced neurodegeneration[53,54]. However, APPSAA mice exhibit particularly prominent behavioral alterations, with cognitive impairment, hyperactivity, and habituation deficits observed in old age[54].

TREM2 is a surface receptor on microglia that regulates microglia function. The researchers found that the elevated density of microglia around Aβ plaques in AD patients may be associated with a mutation in a gene on TREM2 (TREM2 R47H)[55,56]. Based on this theory, the B6J.APOE4.Trem2*R47H mouse model was developed. This model has a humanized ApoE KI mutation, encoding the E4 isoform, and a CRISPR/Cas9-generated R47H point mutation in the Trem2 gene[57]. Exceptionally, this type of mouse model does not produce Aβ plaques or p-tau. Still, at 4-24 months of age, they exhibit age-related progressive deficits in locomotion, coordination, and wheel-running activity, providing insights into age-related pathology beyond the classical features of AD[58].

More mouse models are included in Table 1. While mouse models elucidate mechanistic pathways, their translational limitations underscore the need for models that better replicate AD complexity.

Differences in pathological manifestations and behavioral characteristics among different types of mouse models

| Model | Type | Phenotype | Ref. | |||

| Aβ | p-tau | General observations | Gender difference | |||

| Transgenic models | ||||||

| 3xTg-AD | APPSwe TauP301L PS1M146V | Increases with age in the hippocampus and cortex | Strong signals present at 18 months of age | Increased fear, anxiety, startle response, and freezing behavior | More pronounced in females | [33,59] |

| 5XFAD | APPKM670/671NL*I716V*V717I PS1M146L*L286V | Increases with age in the rostrocaudal axis | A significant increase at 3 months of age, followed by a subsequent decline | Deterioration of sensory functions, decline in cognitive abilities, and emergence of neuropsychiatric symptoms | More pronounced in females | [35,60,61] |

| Tg2576 | APPK670N/M671L | Increases with age | increases with age, as observed at 18 months | Cognitive impairment and behavioral deficits typically emerge by 9 months of age | More pronounced in females | [37,40,62-64] |

| hAβ-KI | (Apptm1.1Aduci) | Rising Aβ40/42 without Aβ plaques | \ | Significant cognitive and memory deficits | Not mentioned | [65] |

| Thy1-ApoE4/C/EBPB | (Thy1-ApoE4 C/EBPB) | Increases with age | Increases with age and has nerve fiber degeneration | Cognitive deficits normal motor function | Not mentioned | [66] |

| Metabolic damage model | ||||||

| d-Galactose mice | Glucose metabolism disorder | Non-occurrence | Non-occurrence | Cognitive and memory impairment (evident in males) | More pronounced in males | [67,68] |

| STZ-icv mice | Glucose deficiency | Aβ42 increases with age | p-Tau increases with age | Memory impairment and cognitive decline | More pronounced in females | [47] |

| STZ-icv rats | Glucose deficiency | Dose-dependent, detectable Aβ as early as 3 months of age | Detectable as early as 1 month of age with time-dependent increase | Rapid decline in the first month of age | Not mentioned | [50,51] |

| KI mouse models | ||||||

| APPSAA | APPSwedish*Arctic*Austrian | Increases with age at 4 and 8 months | Elevated overall levels at 8 months of age | Cognitive impairment, hyperactivity, and habituation deficits | No detected sex effect | [53,54] |

| B6J.APOE4.Trem2*R47H | Apoetm1.1(APOE*4)Adiuj Trem2R47H | Non-occurrence | Non-occurrence | Motor and coordination dysfunction | More pronounced in females | [57] |

| Other AD mouse models | ||||||

| SAM8 | Models of accelerated aging | Significant Aβ deposition | The cortex, striatum, and hippocampus all showed p-tau | Significant decline in learning and memory skills | More pronounced in males | [69-72] |

| Acrolein-induced mice | Acrolein-induced | Aβ secretion rises without significant deposition | Elevated p-tau levels | Mild cognitive impairment with learning and memory loss | Not mentioned | [73,74] |

| AAV1-I2CTF mice | Viral injection | Increased Aβ expression | Elevated p-tau levels Observed neurodegeneration | Learning and memory deficits | Not mentioned | [75] |

| AlCl3 induced mice | Metal ion dysfunction induced | Increased expression of Aβ42 | Elevated p-tau levels | Learning and memory deficits | Experiments were performed on males only | [76,77] |

CAT MODELS

In addition to rodent models, cats can naturally exhibit AD-related pathological features, including Aβ accumulation, NFT formation, and neuronal loss, providing a unique natural model for research[78]. Compared with mouse models that rely on transgenic mutations (which can only simulate partial pathology through artificial intervention), AD-like lesions in cats are characterized by spontaneity and the co-occurrence of multiple pathologies. They are more consistent with the human disease process.

In their study on the brain tissues of cats of different ages, Chambers et al. found that cats over 8 exhibited Aβ deposition, and Aβ42 aggregation could be detected[78,79]. In sections treated with formic acid (FA), extracellular Aβ aggregates were observed in nerve cells throughout the cerebral cortex; these parenchymal Aβ deposits had no central core, which was different from the mature plaques in human AD and AD models of Tg mice. The latest experimental results showed that the youngest cat with extracellular Aβ deposition was only 4 years old[80], and a 4-year-old cat was equivalent to a human aged about 32 years, which was highly consistent with when Aβ began to accumulate in humans (starting from 20 years old)[81,82]. In addition, in cats over 15 years old, Aβ first accumulated in the cortex and then spread to the hippocampus. Moreover, the cortex and hippocampus of cats were most affected by Aβ deposition, while the cerebellum was the least affected (consistent with humans, where the cerebellum is only involved in the final stage of Aβ progression)[7,80,83]. These findings further demonstrate the similarity between Aβ pathology in cats and AD in humans.

Consistent with humans, cats have six isoforms of tau protein, and their p-tau protein possesses many epitopes identical to those found in the human AD brain, such as AT8 and PHF-1 (antibody against tau phosphorylated at the Ser396/404 sites) epitopes[79]. This compensates for the molecular-level limitations of previous transgenic-dependent experimental animals in simulating tau pathology. Regarding pathological manifestations, AT8-positive p-tau can be detected in the cytoplasm of some cat neurons, and its distribution is consistent with that in the human brain; the overall distribution of tau protein also matches the reports in the human brain[79]. These p-tau aggregates often occupy the entire cytoplasm but are present in neurons with normal morphology, thus being identified as pre-tangles[80,84]. Another experiment showed that a large number of NFTs exist in the hippocampus of aged cats (very few in the cerebral cortex), and their distribution is consistent with that of intracellular Aβ, with colocalization with p-tau and ubiquitin. In aged cats with cerebral Aβ deposition and hippocampal NFTs, the number of hippocampal neurons is significantly reduced; however, in cats without NFTs, no apparent neuronal loss is observed even in the presence of Aβ[78]. This feature is consistent with the findings from human AD studies, further demonstrating the unique value of cats as experimental animals in recapitulating the pathological progression of AD. In terms of behavioral characteristics, due to limited research content, the standardization level of behavioral testing for cat models is low. Commonly used AD behavioral tests (such as the MWM and Y-Maze) are rarely applied in cats, lacking standardized protocols, which leads to poor data comparability. Moreover, cognitive deficits in cats are difficult to quantify through simple behavioral tasks, requiring the design of complex environmental enrichment experiments, which are highly challenging to operate.

DOG MODELS

In some studies of older dogs, it has been found that there is a natural decline in cognitive ability in many different areas (including learning and memory), which may reflect neurodegeneration in the brains of older dogs[85]. Using dogs as animal models of AD has unique advantages; domesticated or captive dogs share a familiar environment (including diet) with humans and can better model AD’s polymorphic and multifactorial nature. In addition, dogs have similar pharmacokinetics to humans and can predict drug effectiveness when developing drugs for AD[86]. Taking this a step further, it was found that the cognitive dysfunction in older dogs is related to the Aβ deposition and tau pathology in their brains. The amino acid sequence of Aβ is the same in dogs and humans[87,88]. In the brains of aging dogs, different brain regions show varying degrees of Aβ deposition, which occurs first in the dog’s prefrontal cortex, followed by the temporal cortex, hippocampus, and occipital cortex. This is similar to the distribution in the brains of AD patients[7,89,90]. The formation and maturation of Aβ deposits correlate with the severity of cognitive deficits. They are related to the age and size of the dog, with small and medium-sized dogs having significantly more Aβ deposits in the ventral hippocampal region than large dogs[91]. It has been observed in previous experiments that the prefrontal cortex of older dogs tends to show high levels of Aβ deposition when they show deficits in reversal learning and complex working memory. In contrast, high levels of Aβ deposition occur in the entorhinal cortex when size discrimination and object proximity learning deficits are present[92,93]. The modeling features may be more helpful for us to draw the relationship between changes in brain Aβ levels in AD patients presenting with various cognitive deficits. In AD patients, Aβ is deposited not only outside neuronal cells but also in the cerebral vascular wall, resulting in cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), which disrupts the blood-brain barrier and vascular wall integrity[94-96]. CAA pathology is also frequently seen in older dogs, with deposition of Aβ in both cerebral and peripheral vessel walls, and the most affected region is the frontal cortex, further illustrating the similarities between AD in older dogs and humans[91,97-101]. However, the main component of Aβ deposits in human blood vessels is Aβ40, whereas in aged dogs, it is mainly Aβ40 and Aβ42[102].

In a new study of older dogs with Canine cognitive dysfunction (CCD), researchers performed immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence analyses using the AT8 anti-tau (Ser202, Thr205) antibody. And found that p-tau deposits showed a broad pattern similar to human AD neuropathology but did not co-localise with Aβ plaques[103]. In contrast, in another study, anti-p-tau (Ser396) antibody was additionally added, and Ser396 p-tau protein was found to be significantly elevated in all assessed regions (including frontal lobe, occipital lobe, temporal lobe, internal capsule, and thalamus) in dogs with CCD, except the hippocampus. Interestingly, AT8 immunolabeling in CCD dogs in the latter experiment was sparse and confined to the superficial layers of the inferior temporal lobe, which is inconsistent with the results of the former experiment. The possible reason is that AT8 labeling is considered a relatively late marker of tau-related changes in AD, and the CCD dogs in the latter experiment had not yet reached late progression[104]. Although p-tau can be found in many experiments, no study has confirmed the presence of large numbers of mature NFTs, which is different from human AD[104-106]. And this may also suggest that dementia in dogs may be caused in part by p-tau-induced diminished synaptic function rather than by the toxic effects of NFTs.

Older dogs as natural animal models better reflect the pathophysiology of AD than transgenic mouse models, and testing products for AD in canine models may help determine the efficacy of these compounds in humans. In a development for an Aβ42 vaccine, animal studies showed that it reduced the presence of Aβ plaques in the frontal cortex of the dog’s brain and maintained frontal cortex function[107]. However, over time, the dogs did not improve their cognitive function and had an increased frequency of cerebral microbleeds. This phenomenon was also observed in subsequent clinical human trials[108]. Similar examples include the evaluation of two cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil and phenylserine tartrate) in a canine model[109], where both drugs ameliorated complex working memory impairments in dogs, consistent with subsequent human clinical trial reports[110,111]. In summary, these examples demonstrate the potential effectiveness of old-fashioned dog models in screening therapeutic drugs for attention deficit disorders.

SHEEP MODELS

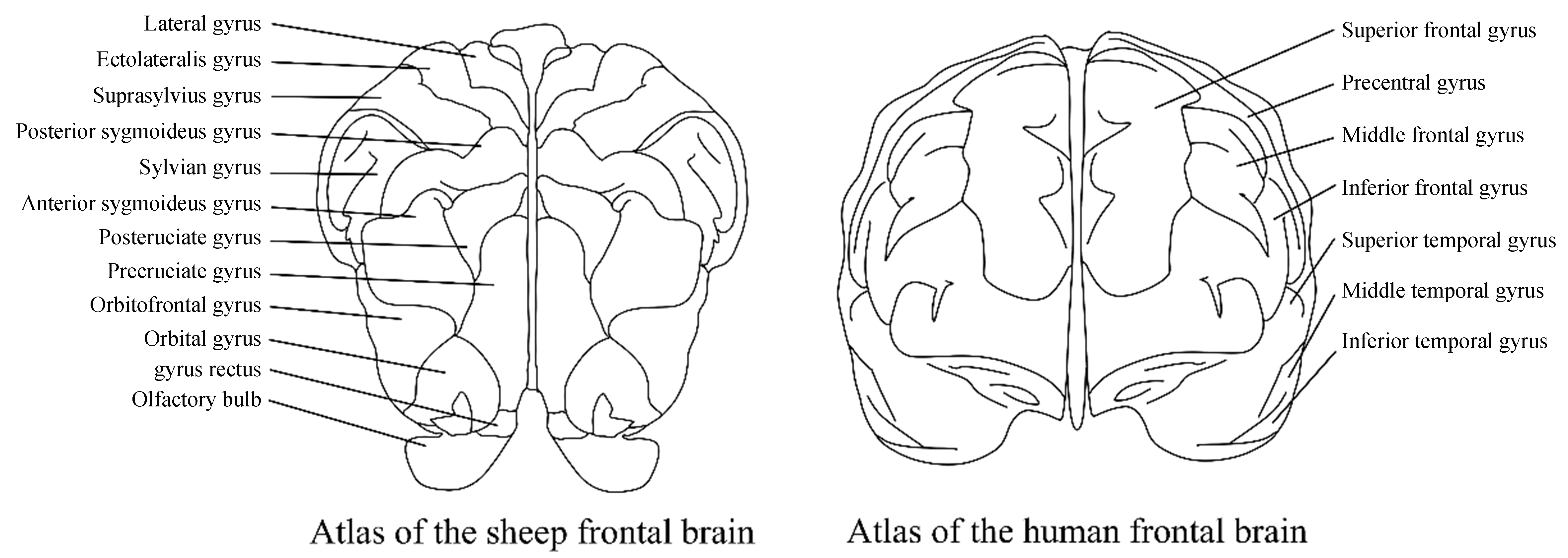

Compared with the above-mentioned models, sheep are more similar to humans in anatomy, neurobiology, lifespan, and genetics, and can make up for the limitations of animal models in simulating human pathology[111]. The brain structure of sheep is highly homologous to that of humans, with a highly gyrencephalic neocortex and distinct differentiation between cortical and subcortical structures[113] [Figure 2]. The amino acid sequences of key AD-related proteins [APP, Aβ42, β-secretase (BACE1), PS1, and presenilin-2 (PS2)] in sheep are highly homologous to those in humans. Although the overall homology of the APOE protein in sheep is the lowest compared with that in humans, the amino acids at its key positions are consistent with those of the human E4 allele[114]. Meanwhile, sheep possess genetic and reproductive advantages that NHPs lack, such as a relatively short gestation period, multiple offspring, and a short time to sexual maturity. Additionally, in terms of ethics and economy, sheep are more suitable for disease research than other large model animals.

Figure 2. Comparison of the human brain and the sheep brain. The “frontal lobe-limbic system connections” and “basic sensory-motor integration frameworks” in sheep share a common evolutionary origin with those in humans in terms of the underlying neural circuits (such as thalamic-frontal projections and limbic system-orbitofrontal connections).

In terms of pathological manifestations, previous studies have detected Aβ and tau lesions in aged sheep[115]. A multi-age detection showed that Aβ42 could be detected in the neurons of sheep over 5 years old, but no Aβ deposition was found. Another study revealed that diffuse Aβ plaques existed in all cortical regions of 8- and 14-year-old sheep, and the number of plaques in 14-year-old sheep was greater than that in 8-year-old sheep. Sheep younger than 8 years old had low p-tau levels (close to the lower limit of detection), and only pre-tangles were observed[114]. In contrast, a large number of mature NFTs could be found in 16- and 21-year-old sheep, suggesting that sheep neuropathology is also age-related[116]. Currently, these studies have not reflected the clinical manifestations of aged sheep, and further research is needed to confirm whether these lesions lead to impairments in sheep’s cognitive and learning functions. The use of sheep in neurodegenerative disease research remains rare, and even rarer in pathological mechanism research. Therefore, sheep may not be suitable for preclinical experimental research on drug mechanisms for the time being, and the focus should be placed on research into pathogenic mechanisms.

NHP MODELS

Although a variety of rodent AD models have been established, their significant evolutionary distance from humans leads to notable differences in biological and behavioral functions, resulting in an extremely low success rate of AD therapeutic drugs in clinical trials. In contrast, NHPs exhibit high homology with humans in terms of anatomy, physiology, neuropathology, aging process, and genomic regulation. The brains of NHPs are not only similar to those of humans in cortical folding, partitioning, and expansion, but also highly homologous in the composition and morphology of cell types, especially astrocytes[117]. Therefore, NHP models have been applied in the research of various neurodegenerative diseases, particularly in preclinical experiments. NHPs can spontaneously develop AD-like pathology. As early as 1985, Struble et al. found a large number of Aβ plaques in the prefrontal and temporal cortices of six aged rhesus monkeys, while Aβ deposition in the hippocampus was relatively low - a finding similar to the condition of human AD patients[118]. Almost all NHP species studied develop amyloid-related lesions with aging, though the types of lesions vary. A study also detected p-tau in aged rhesus monkeys, and this protein can fibrillate into typical paired helical filament tangles[119]. All these observations suggest that NHPs may spontaneously develop AD-like pathological changes.

Spontaneous models

Similar AD pathology has been found in rhesus monkeys in previous investigations, but no studies have elucidated the relationship between their cognitive deficits and the onset of pathology. To elucidate this relationship, a rhesus monkey with cognitive deficits must first be found, then its brain pathology must be examined observationally. In a recent experiment, researchers found evidence that AD occurs naturally in aging rhesus monkeys. By performing the variable spatial delayed response task (VSDRT) and the human intruder test (HIT) on selected rhesus monkeys, the researchers identified three rhesus monkeys with severe cognitive deficits and a significant reduction in responsiveness to the outside world. Pathologic examination of Aβ plaques in the hippocampus, internal olfactory cortex, temporal cortex, and prefrontal cortex of the brains of the three rhesus monkeys revealed that two of the rhesus monkeys displayed significant Aβ plaques in AD-related brain regions. One of the two rhesus monkeys had large numbers of Aβ plaques in the temporal cortex, distributed in the brain parenchyma or around blood vessels. Significant glial cell aggregates were also seen around the Aβ plaques, which were similar to the Aβ plaques in typical patients with late-onset AD[83,120]. Meanwhile, a large amount of p-tau could be detected in these three rhesus monkeys, which was significantly different from the control group. In particular, a large number of NFTs were found in these rhesus monkeys, which are absent in many other models, and immunoelectron microscopy showed that their structure is similar to tangles in the brains of AD patients[119,121]. This may suggest that senescent rhesus monkeys can serve as a typical animal model of AD.

AD-like pathology occurs not only in rhesus monkeys but also in other NHPs. Cynomolgus macaques are one of the closest phylogenetic relatives to us. In a study of Cynomolgus macaques in the middle-aged (mean age 15 years) and elderly (mean age 19 years) groups, it was found that Aβ and p-tau levels were significantly increased in the brains of the elderly group compared to the middle-aged group, with Aβ located essentially within neurons. The density of neurons in the prefrontal cortex was also significantly lower in the older group than in the middle-aged group[122]. Specifically, however, no evidence of the presence of NFTs was found in the aged group. Instead, some markers of pre-tangling were observed in the middle-aged group (elevated levels of tau phosphorylation at the Thr231 locus)[122,123]. Similarly, neuropathology similar to AD can be observed in another species of NHPs, the Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus. Aβ plaques could be found in the cortex of all the older groups (mean age 21 years) and were most dense in the temporal lobe cortex, especially in the middle-superior temporal gyrus[124]. In the middle-aged group (mean age 11 years), Aβ plaques were present only individually. In tau pathology, although the number of areas positive for p-tau immunoreactivity was greater in the older group than in the middle-aged group, it was not statistically significant[124]. Interestingly, little or no nerve fiber deformation could be observed in the brains of Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus and Cynomolgus macaques.

Aβ injection model

To reproduce the apparent NFT seen in patients with AD, the researchers constructed new models by repeatedly injecting AβOs into the brain parenchyma of aged Cynomolgus macaques[125]. Neuropathological staging of Alzheimer-related changes. The number and load of Aβ plaques in the seven AβO monkeys were significantly higher than in control monkeys and were primarily distributed in the gray matter of the limbic structures and neocortex, with dense plaque cores similar to those in AD patients. Observation under confocal electron microscopy revealed that the curly filament bundles in cell bodies and the droplet inclusions in long axons, resembling strings of pearls, were identical to the typical NFT structures in AD patients[125,126]. More unusually, the researchers found neurodegeneration in different brain regions of AβO, distributed around the Aβ plaques[125]. These characterizations suggest that aged Cynomolgus macaques injected with AβO could serve as a model of AD for future drug experiments.

Applications of NHPs

NHP models have been widely used in AD research. As a primary approach of active immunotherapy, vaccines represent a long-sought effective preventive strategy. As early as 2004, Lemere et al. demonstrated that Aβ vaccination in NHPs could reduce Aβ levels in cerebrospinal fluid[127]. AV-1959D, a DNA vaccine developed to induce anti-Aβ antibody generation, has demonstrated potent Aβ antibody responses in macaques without triggering deleterious autoreactive T cell activation in preclinical studies[128,129]. Currently, AV-1959D has progressed to Phase I clinical trials (NCT05642429). Should its safety profile be confirmed, subsequent studies will focus on preventive applications in high-risk populations. NHP models also serve as valuable tools for investigating pathogenesis-related therapeutic interventions in AD. Pathological alterations in neural circuits and synaptic connections have been established as critical contributors to cognitive impairment in AD. Notably, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has been demonstrated to prevent lesion-induced neuronal death in the entorhinal cortex, reverse neuronal atrophy, and ameliorate age-related cognitive deficits in both adult and aged rhesus monkeys[130]. Building upon these preliminary findings, an AAV2-BDNF gene therapy approach has advanced to Phase I clinical trials (NCT05040217).

With the advancement of AI and molecular profiling technologies, the use of NHPs as AD models offers unique advantages[131,132]. Firstly, NHPs exhibit far higher sequence homology with humans in core AD-related molecules (genes, proteins, metabolites) than rodents, enabling direct capture of molecular changes more closely resembling those in human AD and avoiding molecular profiling biases caused by species differences in rodents. Secondly, human AD is often accompanied by comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease) and a complex intracerebral microenvironment (neuroinflammation, blood-brain barrier impairment), and NHPs are also susceptible to these risk factors[133]. The application of this combination - molecular profiling using NHP models - is particularly suitable for core research directions such as early AD intervention, deciphering complex pathological mechanisms, and developing clinically translatable biomarkers, serving as a key technology-model system bridging basic research and human clinical trials.

PERSPECTIVES

After the first discovery of AD more than 100 years ago, AD’s underlying etiology and pathogenesis have been studied in depth, based on which many animal models have been designed. However, AD has a long course, many neurologic pathologic changes, and most ADs are late-onset, with many etiologic and influencing factors. Until now, no animal model has completely replicated the whole process of human AD pathogenesis. There are still many challenges in using animal models for AD research. First, aging is a critical risk factor for LOSAD, as evidenced by many animal model studies, which often focus on the earlier age range of the animal or a specific age stage, thereby overlooking the slow, gradual nature of AD. Second, rodent models widely used in AD research have significant differences in anatomy, brain development, and pharmacological effects from humans. Finally, while naturally occurring types of AD models can maximize the expression of pathological and clinical symptoms similar to those of human AD, they require higher financial costs, scarcer sample sizes, and more specialized researchers and facilities.

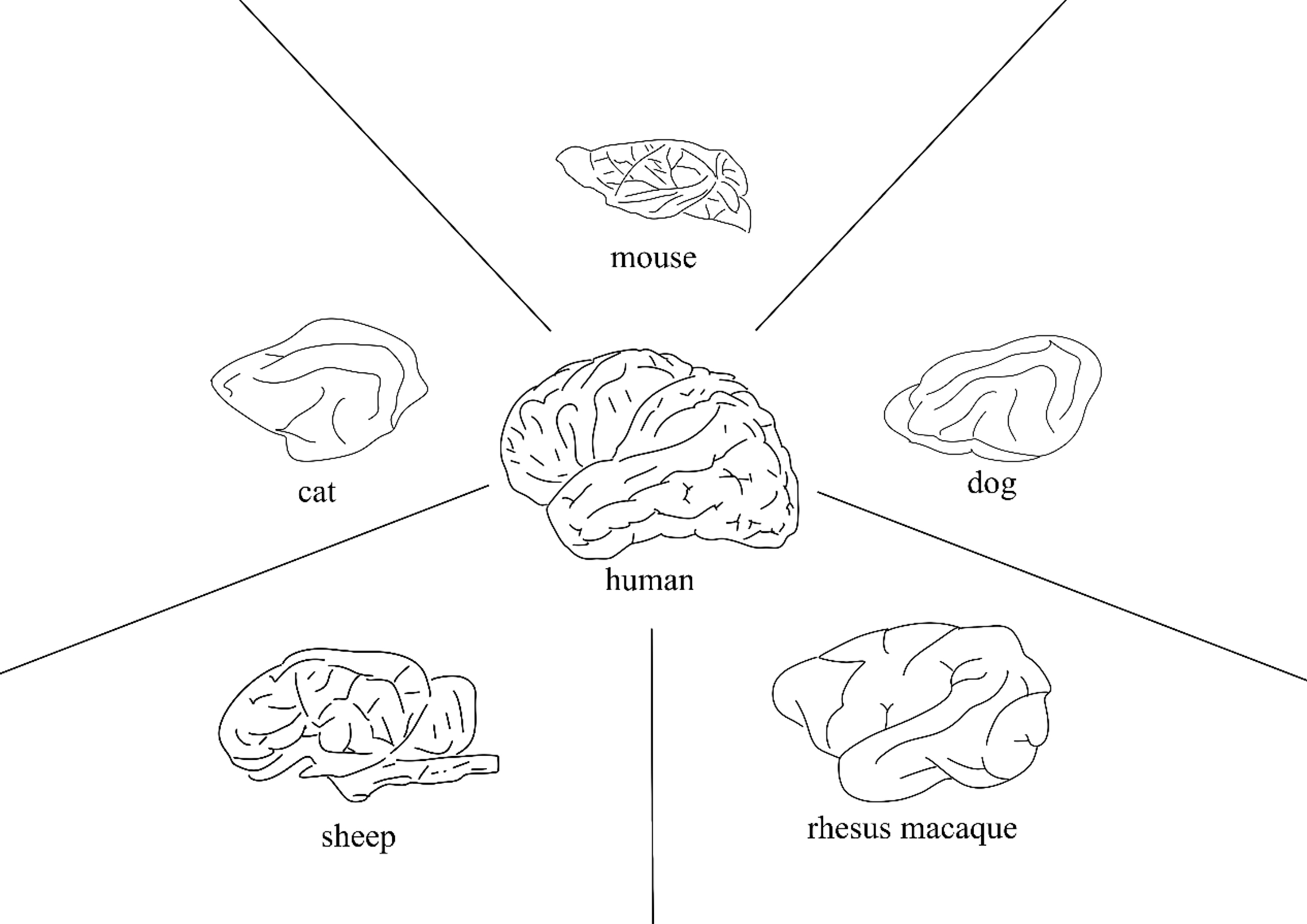

In response to these challenges, corresponding measures can be adopted to address them in future research. Given that most mouse models develop the disease at a relatively early age, researchers can design accelerated aging models to study the pathological characteristics of AD in aged mice. This approach can resolve the issues of long-term consumption, high labor intensity, and high costs associated with natural aging mouse models. Relevant experimental studies have already been carried out in this direction[134,135]. Similarly, these accelerated aging methods can also be applied to animal models such as cats and dogs, as discussed in this paper. Spontaneous large animal models exhibit a high degree of pathological similarity to humans, with systemic functions and anatomical structures (particularly cerebral architecture [Figure 3]) closely resembling those of humans. In terms of size, the brain tissue of natural animal models is larger. A single sample collection can be employed for multiple experiments or a variety of experimental applications. Therefore, preclinical trials for novel therapeutics should ideally be conducted in animal models with minimal species differences from humans to achieve the desired clinical outcomes. Regarding the challenges of high costs and limited sample sizes associated with large animal models, future solutions may involve establishing large-scale centralized facilities for large animal models to reduce production and maintenance expenses. Additionally, computational modeling techniques - such as molecular dynamics simulations and absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) prediction models - could be employed for preliminary drug screening and evaluation, thereby minimizing the number and scale of animal experiments while reducing experimental costs.

Figure 3. A brief comparison of brain size and structure among various animal models. Cats, dogs, and sheep exhibit greater similarities to humans in specific functional brain regions (such as vision, emotion, and hemispheric differentiation). Monkeys demonstrate a high degree of homology with humans in overall brain structure, particularly in the advanced cortex.

Currently, there are no definitive, effective, and validated therapeutic regimens for AD applicable to the majority of patients. Future model development should prioritize AD drug development, with systematic pre-clinical evaluation of drug pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, tolerability, and safety. By leveraging technological innovations and modern biotechnologies, the establishment of widely accepted standardized AD models - alongside their comprehensive evaluation - will significantly accelerate the progression of AD drug clinical trials.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Wrote the review paper: Yang W

Revised manuscript: Yu Z, Wang W, Yan S

Conceived and designed experiments: Yan S, Yang W

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors gratefully acknowledges the support of the K.C. Wong Education Foundation. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA0805300 to Yan S) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82171244 to Yan S, 32470564 to Yan S).

Conflicts of interest

Yan S is a member of the Youth Editorial Board of the journal Ageing and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Yan S was not involved in any part of the editorial process, including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Gustavsson A, Norton N, Fast T, et al. Global estimates on the number of persons across the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19:658-70.

2. Gumus M, Multani N, Mack ML, Tartaglia MC; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Progression of neuropsychiatric symptoms in young-onset versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Geroscience. 2021;43:213-23.

3. Tellechea P, Pujol N, Esteve-Belloch P, et al. Early- and late-onset Alzheimer disease: are they the same entity? Neurologia. 2018;33:244-53.

4. Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:208-45.

5. Trejo-Lopez JA, Yachnis AT, Prokop S. Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19:173-85.

7. Thal DR, Rüb U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58:1791-800.

8. Johnson GV, Bailey CD. The p38 MAP kinase signaling pathway in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2003;183:263-8.

9. Puzzo D, Privitera L, Leznik E, et al. Picomolar amyloid-beta positively modulates synaptic plasticity and memory in hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14537-45.

10. Gu L, Guo Z. Alzheimer’s Aβ42 and Aβ40 peptides form interlaced amyloid fibrils. J Neurochem. 2013;126:305-11.

11. Li S, Hong S, Shepardson NE, Walsh DM, Shankar GM, Selkoe D. Soluble oligomers of amyloid Beta protein facilitate hippocampal long-term depression by disrupting neuronal glutamate uptake. Neuron. 2009;62:788-801.

12. Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837-42.

13. Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Furlow PW, et al. Abeta oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27:796-807.

14. Brothers HM, Gosztyla ML, Robinson SR. The physiological roles of amyloid-β peptide hint at new ways to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:118.

15. Sadigh-Eteghad S, Sabermarouf B, Majdi A, Talebi M, Farhoudi M, Mahmoudi J. Amyloid-beta: a crucial factor in Alzheimer’s disease. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24:1-10.

16. Medeiros R, Baglietto-Vargas D, LaFerla FM. The role of tau in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17:514-24.

17. Götz J, Chen F, van Dorpe J, Nitsch RM. Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301l tau transgenic mice induced by Abeta 42 fibrils. Science. 2001;293:1491-5.

18. Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong CX, Alonso Adel C, Grundke-Iqbal I. Mechanisms of tau-induced neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:53-69.

19. Alonso A, Zaidi T, Novak M, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Hyperphosphorylation induces self-assembly of tau into tangles of paired helical filaments/straight filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6923-8.

20. Le Corre S, Klafki HW, Plesnila N, et al. An inhibitor of tau hyperphosphorylation prevents severe motor impairments in tau transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9673-8.

21. Santacruz K, Lewis J, Spires T, et al. Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science. 2005;309:476-81.

22. Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, et al.; Bapineuzumab 301 and 302 Clinical Trial Investigators. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:322-33.

23. Ittner LM, Götz J. Amyloid-β and tau--a toxic pas de deux in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:65-72.

24. Iijima K, Gatt A, Iijima-Ando K. Tau Ser262 phosphorylation is critical for Abeta42-induced tau toxicity in a transgenic Drosophila model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2947-57.

25. Zheng WH, Bastianetto S, Mennicken F, Ma W, Kar S. Amyloid beta peptide induces tau phosphorylation and loss of cholinergic neurons in rat primary septal cultures. Neuroscience. 2002;115:201-11.

26. Hernandez P, Lee G, Sjoberg M, Maccioni RB. Tau phosphorylation by cdk5 and Fyn in response to amyloid peptide Abeta (25-35): involvement of lipid rafts. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:149-56.

27. Terwel D, Muyllaert D, Dewachter I, et al. Amyloid activates GSK-3beta to aggravate neuronal tauopathy in bigenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:786-98.

28. Ittner LM, Ke YD, Delerue F, et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142:387-97.

29. Tezuka T, Umemori H, Akiyama T, Nakanishi S, Yamamoto T. PSD-95 promotes Fyn-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit NR2A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:435-40.

30. Decker H, Jürgensen S, Adrover MF, et al. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors are required for synaptic targeting of Alzheimer’s toxic amyloid-β peptide oligomers. J Neurochem. 2010;115:1520-9.

31. Granzotto A, Vissel B, Sensi SL. Lost in translation: inconvenient truths on the utility of mouse models in Alzheimer’s disease research. Elife. 2024;13:e90633.

32. Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, et al. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409-21.

33. Javonillo DI, Tran KM, Phan J, et al. Systematic phenotyping and characterization of the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:785276.

34. Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10129-40.

35. Forner S, Kawauchi S, Balderrama-Gutierrez G, et al. Systematic phenotyping and characterization of the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Data. 2021;8:270.

36. Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, et al. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99-102.

37. Klingner M, Apelt J, Kumar A, et al. Alterations in cholinergic and non-cholinergic neurotransmitter receptor densities in transgenic Tg2576 mouse brain with beta-amyloid plaque pathology. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2003;21:357-69.

38. Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, Saido TC, Shoji M, Ashe KH, Younkin SG. Age-dependent changes in brain, CSF, and plasma amyloid (beta) protein in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:372-81.

39. Unger C, Hedberg MM, Mustafiz T, Svedberg MM, Nordberg A. Early changes in Abeta levels in the brain of APPswe transgenic mice - implication on synaptic density, alpha7 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine- and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor levels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;30:218-27.

40. Kawarabayashi T, Shoji M, Younkin LH, et al. Dimeric amyloid beta protein rapidly accumulates in lipid rafts followed by apolipoprotein E and phosphorylated tau accumulation in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3801-9.

41. Zhang Z, Song M, Liu X, et al. Cleavage of tau by asparagine endopeptidase mediates the neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2014;20:1254-62.

42. Zhang Z, Song M, Liu X, et al. Delta-secretase cleaves amyloid precursor protein and regulates the pathogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8762.

43. Xia Y, Wang ZH, Zhang J, et al. C/EBPβ is a key transcription factor for APOE and preferentially mediates ApoE4 expression in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:6002-22.

44. Correia SC, Santos RX, Perry G, Zhu X, Moreira PI, Smith MA. Insulin-resistant brain state: the culprit in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease? Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:264-73.

45. de la Monte SM, Tong M. Brain metabolic dysfunction at the core of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88:548-59.

46. Kamat PK, Kalani A, Rai S, Tota SK, Kumar A, Ahmad AS. Streptozotocin intracerebroventricular-induced neurotoxicity and brain insulin resistance: a therapeutic intervention for treatment of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (sAD)-like pathology. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:4548-62.

47. Ravelli KG, Rosário BD, Camarini R, Hernandes MS, Britto LR. Intracerebroventricular streptozotocin as a model of Alzheimer’s disease: neurochemical and behavioral characterization in mice. Neurotox Res. 2017;31:327-33.

48. Agrawal R, Mishra B, Tyagi E, Nath C, Shukla R. Effect of curcumin on brain insulin receptors and memory functions in STZ (ICV) induced dementia model of rat. Pharmacol Res. 2010;61:247-52.

49. Chen Y, Liang Z, Blanchard J, et al. A non-transgenic mouse model (icv-STZ mouse) of Alzheimer’s disease: similarities to and differences from the transgenic model (3xTg-AD mouse). Mol Neurobiol. 2013;47:711-25.

50. Shingo AS, Kanabayashi T, Murase T, Kito S. Cognitive decline in STZ-3V rats is largely due to dysfunctional insulin signalling through the dentate gyrus. Behav Brain Res. 2012;229:378-83.

51. Knezovic A, Osmanovic-Barilar J, Curlin M, et al. Staging of cognitive deficits and neuropathological and ultrastructural changes in streptozotocin-induced rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2015;122:577-92.

52. Sasaguri H, Nilsson P, Hashimoto S, et al. APP mouse models for Alzheimer’s disease preclinical studies. EMBO J. 2017;36:2473-87.

53. Xia D, Lianoglou S, Sandmann T, et al. Novel App knock-in mouse model shows key features of amyloid pathology and reveals profound metabolic dysregulation of microglia. Mol Neurodegener. 2022;17:41.

54. Lu W, Shue F, Kurti A, et al. Amyloid pathology and cognitive impairment in hAβ-KI and APPSAA-KI mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2025;145:13-23.

55. Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, et al.; Alzheimer Genetic Analysis Group. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:117-27.

56. Jonsson T, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, et al. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:107-16.

57. Kotredes KP, Oblak A, Pandey RS, et al. Uncovering disease mechanisms in a novel mouse model expressing humanized APOEε4 and Trem2*R47H. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:735524.

58. Wang Q, Zhu BT, Lei P. Animal models of Alzheimer’s disease: current strategies and new directions. Zool Res. 2024;45:1385-407.

59. Sterniczuk R, Antle MC, Laferla FM, Dyck RH. Characterization of the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: Part 2. Behavioral and cognitive changes. Brain Res. 2010;1348:149-55.

60. Pádua MS, Guil-Guerrero JL, Lopes PA. Behaviour hallmarks in Alzheimer’s disease 5xFAD mouse model. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:6766.

61. Eimer WA, Vassar R. Neuron loss in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease correlates with intraneuronal Aβ42 accumulation and Caspase-3 activation. Mol Neurodegener. 2013;8:2.

62. Schmid S, Rammes G, Blobner M, et al. Cognitive decline in Tg2576 mice shows sex-specific differences and correlates with cerebral amyloid-beta. Behav Brain Res. 2019;359:408-17.

63. Deacon RMJ, Cholerton LL, Talbot K, et al. Age-dependent and -independent behavioral deficits in Tg2576 mice. Behav Brain Res. 2008;189:126-38.

64. King DL, Arendash GW. Behavioral characterization of the Tg2576 transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease through 19 months. Physiol Behav. 2002;75:627-42.

65. Baglietto-Vargas D, Forner S, Cai L, et al. Generation of a humanized Aβ expressing mouse demonstrating aspects of Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2421.

66. Wang ZH, Xia Y, Wu Z, et al. Neuronal ApoE4 stimulates C/EBPβ activation, promoting Alzheimer’s disease pathology in a mouse model. Prog Neurobiol. 2022;209:102212.

67. Parameshwaran K, Irwin MH, Steliou K, Pinkert CA. D-galactose effectiveness in modeling aging and therapeutic antioxidant treatment in mice. Rejuvenation Res. 2010;13:729-35.

68. Hao L, Huang H, Gao J, Marshall C, Chen Y, Xiao M. The influence of gender, age and treatment time on brain oxidative stress and memory impairment induced by D-galactose in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2014;571:45-9.

69. Butterfield DA, Poon HF. The senescence-accelerated prone mouse (SAMP8): a model of age-related cognitive decline with relevance to alterations of the gene expression and protein abnormalities in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:774-83.

70. Petursdottir AL, Farr SA, Morley JE, Banks WA, Skuladottir GV. Lipid peroxidation in brain during aging in the senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM). Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1170-8.

71. Del Valle J, Duran-Vilaregut J, Manich G, et al. Early amyloid accumulation in the hippocampus of SAMP8 mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:1303-15.

72. Morley JE, Armbrecht HJ, Farr SA, Kumar VB. The senescence accelerated mouse (SAMP8) as a model for oxidative stress and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:650-6.

73. Huang YJ, Jin MH, Pi RB, et al. Acrolein induces Alzheimer’s disease-like pathologies in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol Lett. 2013;217:184-91.

74. Rashedinia M, Lari P, Abnous K, Hosseinzadeh H. Protective effect of crocin on acrolein-induced tau phosphorylation in the rat brain. Acta Neurobiol Exp. 2015;75:208-19.

75. Wang X, Blanchard J, Kohlbrenner E, et al. The carboxy-terminal fragment of inhibitor-2 of protein phosphatase-2A induces Alzheimer disease pathology and cognitive impairment. FASEB J. 2010;24:4420-32.

76. Rui D, Yongjian Y. Aluminum chloride induced oxidative damage on cells derived from hippocampus and cortex of ICR mice. Brain Res. 2010;1324:96-102.

77. Chakrabarty M, Bhat P, Kumari S, et al. Cortico-hippocampal salvage in chronic aluminium induced neurodegeneration by Celastrus paniculatus seed oil: neurobehavioural, biochemical, histological study. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2012;3:161-71.

78. Chambers JK, Tokuda T, Uchida K, et al. The domestic cat as a natural animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:78.

79. Head E, Moffat K, Das P, et al. Beta-amyloid deposition and tau phosphorylation in clinically characterized aged cats. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:749-63.

80. Sordo L, Martini AC, Houston EF, Head E, Gunn-Moore D. Neuropathology of aging in cats and its similarities to human Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging. 2021;2:684607.

81. Gonneaud J, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Mézenge F, et al. Increased florbetapir binding in the temporal neocortex from age 20 to 60 years. Neurology. 2017;89:2438-46.

82. Quimby J, Gowland S, Carney HC, DePorter T, Plummer P, Westropp J. 2021 AAHA/AAFP Feline Life Stage Guidelines. J Feline Med Surg. 2021;23:211-33.

83. Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239-59.

84. Ikeda K, Akiyama H, Arai T, Nishimura T. Glial tau pathology in neurodegenerative diseases: their nature and comparison with neuronal tangles. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:S85-91.

85. Araujo JA, Baulk J, de Rivera C. The aged dog as a natural model of Alzheimer’s disease progression. In: Landsberg G, Maďari A, Žilka N, editors. Canine and feline dementia. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. pp. 69-92.

86. Studzinski CM, Araujo JA, Milgram NW. The canine model of human cognitive aging and dementia: pharmacological validity of the model for assessment of human cognitive-enhancing drugs. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:489-98.

87. Johnstone EM, Chaney MO, Norris FH, Pascual R, Little SP. Conservation of the sequence of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid peptide in dog, polar bear and five other mammals by cross-species polymerase chain reaction analysis. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1991;10:299-305.

88. Selkoe DJ, Bell DS, Podlisny MB, Price DL, Cork LC. Conservation of brain amyloid proteins in aged mammals and humans with Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 1987;235:873-7.

89. Giaccone G, Verga L, Finazzi M, et al. Cerebral preamyloid deposits and congophilic angiopathy in aged dogs. Neurosci Lett. 1990;114:178-83.

90. Head E, McCleary R, Hahn FF, Milgram NW, Cotman CW. Region-specific age at onset of beta-amyloid in dogs. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:89-96.

91. Schmidt F, Boltze J, Jäger C, et al. Detection and quantification of β-amyloid, pyroglutamyl Aβ, and tau in aged canines. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2015;74:912-23.

92. Head E, Callahan H, Muggenburg BA, Cotman CW, Milgram NW. Visual-discrimination learning ability and beta-amyloid accumulation in the dog. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:415-25.

93. Cummings BJ, Head E, Afagh AJ, Milgram NW, Cotman CW. Beta-amyloid accumulation correlates with cognitive dysfunction in the aged canine. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1996;66:11-23.

94. Attems J, Jellinger KA, Lintner F. Alzheimer’s disease pathology influences severity and topographical distribution of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110:222-31.

95. Herzig MC, Van Nostrand WE, Jucker M. Mechanism of cerebral beta-amyloid angiopathy: murine and cellular models. Brain Pathol. 2006;16:40-54.

96. Prior R, D’Urso D, Frank R, Prikulis I, Pavlakovic G. Loss of vessel wall viability in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neuroreport. 1996;7:562-4.

97. Ishihara T, Gondo T, Takahashi M, et al. Immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopical characterization of cerebrovascular and senile plaque amyloid in aged dogs’ brains. Brain Res. 1991;548:196-205.

98. Shimada A, Kuwamura M, Awakura T, et al. Topographic relationship between senile plaques and cerebrovascular amyloidosis in the brain of aged dogs. J Vet Med Sci. 1992;54:137-44.

99. Colle MA, Hauw JJ, Crespeau F, et al. Vascular and parenchymal Abeta deposition in the aging dog: correlation with behavior. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:695-704.

100. Rusbridge C, Salguero FJ, David MA, et al. An aged canid with behavioral deficits exhibits blood and cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta oligomers. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:7.

101. Mesquita LLR, Mesquita LP, Wadt D, Bruhn FRP, Maiorka PC. Heterogenous deposition of β-amyloid in the brain of aged dogs. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;99:44-52.

102. Chambers JK, Uchida K, Nakayama H. White matter myelin loss in the brains of aged dogs. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:263-9.

103. Habiba U, Ozawa M, Chambers JK, et al. Neuronal deposition of amyloid-β oligomers and hyperphosphorylated tau is closely connected with cognitive dysfunction in aged dogs. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2021;5:749-60.

104. Abey A, Davies D, Goldsbury C, Buckland M, Valenzuela M, Duncan T. Distribution of tau hyperphosphorylation in canine dementia resembles early Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies. Brain Pathol. 2021;31:144-62.

105. Smolek T, Madari A, Farbakova J, et al. Tau hyperphosphorylation in synaptosomes and neuroinflammation are associated with canine cognitive impairment. J Comp Neurol. 2016;524:874-95.

106. Pugliese M, Mascort J, Mahy N, Ferrer I. Diffuse beta-amyloid plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau are unrelated processes in aged dogs with behavioral deficits. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:175-83.

107. Head E, Pop V, Vasilevko V, et al. A two-year study with fibrillar beta-amyloid (Abeta) immunization in aged canines: effects on cognitive function and brain Abeta. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3555-66.

108. Davis PR, Giannini G, Rudolph K, et al. Aβ vaccination in combination with behavioral enrichment in aged beagles: effects on cognition, Aβ, and microhemorrhages. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;49:86-99.

109. Araujo JA, Greig NH, Ingram DK, Sandin J, de Rivera C, Milgram NW. Cholinesterase inhibitors improve both memory and complex learning in aged beagle dogs. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26:143-55.

110. Birks JS, Harvey RJ. Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD001190.

111. Vecchio I, Sorrentino L, Paoletti A, Marra R, Arbitrio M. The state of the art on acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2021;13:11795735211029113.

112. Yu Z, Yang W, Yan S. Advantages and differences among various animal models of Huntington’s disease. Ageing Neur Dis. 2024;4:13.

113. Morton AJ, Howland DS. Large genetic animal models of Huntington’s disease. J Huntingtons Dis. 2013;2:3-19.

114. Reid SJ, Mckean NE, Henty K, et al. Alzheimer’s disease markers in the aged sheep (Ovis aries). Neurobiol Aging. 2017;58:112-9.

115. Nelson PT, Greenberg SG, Saper CB. Neurofibrillary tangles in the cerebral cortex of sheep. Neurosci Lett. 1994;170:187-90.

116. Davies ES, Morphew RM, Cutress D, Morton AJ, McBride S. Characterization of microtubule-associated protein tau isoforms and Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology in normal sheep (Ovis aries): relevance to their potential as a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79:560.

117. Han L, Wei X, Liu C, et al. Cell transcriptomic atlas of the non-human primate Macaca fascicularis. Nature. 2022;604:723-31.

118. Struble RG, Price DL Jr, Cork LC, Price DL. Senile plaques in cortex of aged normal monkeys. Brain Res. 1985;361:267-75.

119. Paspalas CD, Carlyle BC, Leslie S, et al. The aged rhesus macaque manifests Braak stage III/IV Alzheimer’s-like pathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:680-91.

120. Li Z, He X, Wu S, et al. Naturally occurring Alzheimer’s disease in rhesus monkeys. BioRxiv. 2022.

121. Rissman RA, Poon WW, Blurton-Jones M, et al. Caspase-cleavage of tau is an early event in Alzheimer disease tangle pathology. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:121-30.

122. Jester HM, Gosrani SP, Ding H, Zhou X, Ko MC, Ma T. Characterization of early Alzheimer’s disease-like pathological alterations in non-human primates with aging: a pilot study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;88:957-70.

123. Neddens J, Temmel M, Flunkert S, et al. Phosphorylation of different tau sites during progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018;6:52.

124. Latimer CS, Shively CA, Keene CD, et al. A nonhuman primate model of early Alzheimer’s disease pathologic change: implications for disease pathogenesis. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:93-105.

125. Yue F, Feng S, Lu C, et al. Synthetic amyloid-β oligomers drive early pathological progression of Alzheimer’s disease in nonhuman primates. iScience. 2021;24:103207.

126. Augustinack JC, Schneider A, Mandelkow EM, Hyman BT. Specific tau phosphorylation sites correlate with severity of neuronal cytopathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;103:26-35.

127. Lemere CA, Beierschmitt A, Iglesias M, et al. Alzheimer’s disease abeta vaccine reduces central nervous system abeta levels in a non-human primate, the Caribbean vervet. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:283-97.

128. Vukicevic M, Fiorini E, Siegert S, et al. An amyloid beta vaccine that safely drives immunity to a key pathological species in Alzheimer’s disease: pyroglutamate amyloid beta. Brain Commun. 2022;4:fcac022.

129. Triplett O, Varda N, Decourt B, Vasconcellos R, Sabbagh MN. Active immunization targeting amyloid β for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2025;25:202-17.

130. Nagahara AH, Merrill DA, Coppola G, et al. Neuroprotective effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rodent and primate models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2009;15:331-7.

131. Seyfried NT, Dammer EB, Swarup V, et al. A multi-network approach identifies protein-specific co-expression in asymptomatic and symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Syst. 2017;4:60-72.e4.

132. Swarup V, Hinz FI, Rexach JE, et al.; International Frontotemporal Dementia Genomics Consortium. Identification of evolutionarily conserved gene networks mediating neurodegenerative dementia. Nat Med. 2019;25:152-64.

133. Mattison JA, Vaughan KL. An overview of nonhuman primates in aging research. Exp Gerontol. 2017;94:41-5.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].