Sex-specific differences in women’s hypertension management

Abstract

Hypertension is a major contributor to the development of cardiovascular disease, and effective blood pressure control is a critical intervention for reducing cardiovascular events. While age-adjusted awareness rates among women surpass those of their male counterparts, gender-specific control rates remain suboptimal. A rigorous pharmacological assessment and evidence-based prescription of antihypertensive agents, meticulously aligned with their distinct mechanistic and therapeutic profiles, constitute a cornerstone of clinical practice. This review examines the distinct epidemiological, pathophysiological, and clinical characteristics of hypertension in women, highlighting gender-specific differences across various life stages. Key topics addressed include hormonal influences, risk factors, pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders, menopause-associated hypertension, and sex-specific responses to treatment. The review emphasizes the importance of tailored management strategies and individualized antihypertensive therapy to improve outcomes in women.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

As a primary modifiable risk factor, hypertension plays a crucial role in the cardiovascular disease (CVD), and exhibits significant sex-specific differences in epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical outcomes. While historically viewed through a unisex lens, emerging evidence highlights that biological, hormonal, and psychosocial distinctions critically influence hypertension development and management in women[1,2]. Globally, women face unique challenges across their lifespan: young women in reproductive years contend with pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders (e.g., preeclampsia), which confer lifelong cardiovascular risks[1,3,4]; perimenopausal hormonal shifts exacerbate arterial stiffness and metabolic dysregulation[5-7]; and older women disproportionately suffer from obesity-driven hypertension and resistant phenotypes[1,5].

The pathophysiology of hypertension in women is intricately tied to sex hormones. Estrogen’s vascular protective effects diminish post-menopause, coinciding with accelerated arterial stiffening, sympathetic hyperactivity, and salt sensitivity[1,2]. Conversely, androgens and psychosocial stressors - such as chronic stress and depression - further disrupt neuroendocrine balance[1,2]. Pregnancy acts as a “stress test”, unmasking latent cardiovascular vulnerabilities[8,9]. Clinically, women experience differential responses to antihypertensive therapies, but critical gaps persist in sex-stratified research, particularly regarding novel therapies such as renal denervation (RDN) and angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs)[2].

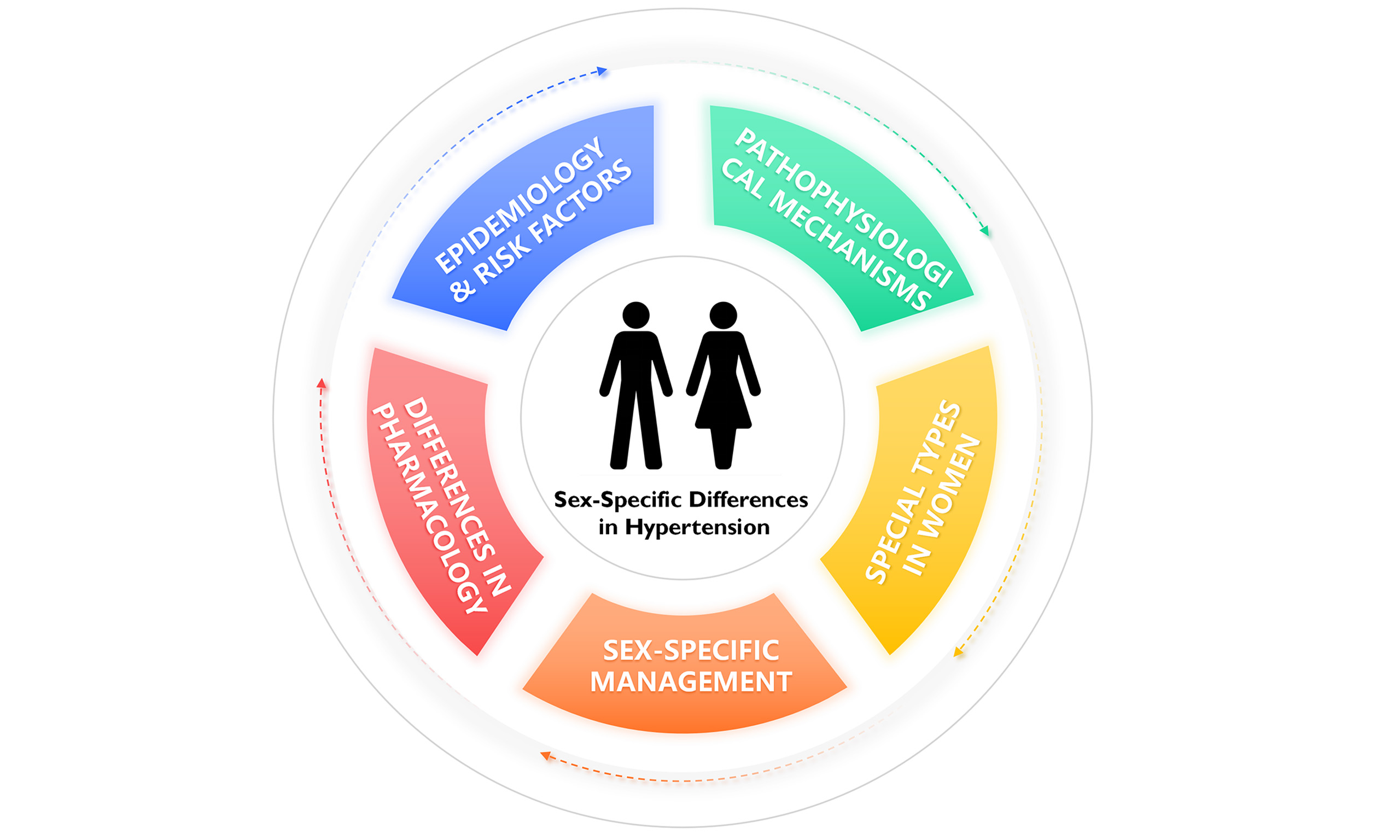

This review synthesizes contemporary evidence on gender disparities in hypertension management, emphasizing hormonal, vascular, and psychosocial contributors. By delineating sex-specific risk factors, pathophysiological mechanisms, management strategies, lifestyle interventions and special types of hypertension in women [Figure 1], we aim to address the unmet needs of hypertensive women across their lifespan.

EPIDEMIOLOGY & RISK FACTORS

For population health surveillance, hypertension is typically defined as having a systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg, or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg, or currently taking antihypertensive medication. It is estimated that hypertension affects approximately 33% of adults aged 30-79 worldwide[10]. Globally, the prevalence of hypertension is slightly higher in men (34%) than in women (32%). This male predominance is often age-related, with the gap being more pronounced in individuals younger than 50 years[11]. This pattern of lower hypertension prevalence among women aged under 50 years holds in most countries worldwide[11]. However, for people aged 50-79 years, both men and women globally are estimated to have equivalent hypertension prevalence of 49%[10]. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in the United States show that the prevalence of hypertension among women reaches 75% in those aged 65-74 and rises to 85% in those over 75 years old[12,13]. The prevalence of hypertension in women increases sharply between the ages of 45-54 and surpasses that in men after 60-65 years old[1,12]. A sex-specific analysis from a 43-year longitudinal study (1971-2014) of blood pressure (BP) measurements in 32,833 participants (54% female) across four United States community cohorts revealed that women experience more pronounced age-related increases in both systolic and diastolic BP compared with men[14]. The China Hypertension Survey (2012-2015) indicated that the prevalence of hypertension among women increased from 10.9% in 1991 to 21.5% in 2012-2015, compared with an increase from 11.4% to 24.5% among men during the same periods[15,16].

Hypertension represents a major risk factor for CVD-related illness and death in women. Globally, it is estimated that approximately 600 million women have high BP; this figure includes hypertension occurring during pregnancy, which is a primary cause of maternal mortality[13]. Research by Xia et al. demonstrated that women at high CVD risk have higher hypertension prevalence than men (56.6% vs. 41.7%), while women with established CVD show lower prevalence than men (51.7% vs. 54.8%). Compared to younger women and men of the same age, elderly women exhibit more severe hypertension and poorer control rates[17]. Longitudinal cohort analyses reveal a sex/age interaction gradient in hypertensive burden: postmenopausal women (≥ 55 years) demonstrate higher systolic pressure trajectories (Δ = 7.2 mmHg, 95% confidence interval (CI) 5.8-8.6) and 39% wider pulse pressure variability (P < 0.001) compared to premenopausal counterparts, while maintaining 23% lower control rates than age-matched males (odds ratio (OR) 0.77, 95%CI: 0.69-0.85). Contemporary global burden analyses (GBD 2023) reveal alarming hypertension management gaps: age-standardized detection rates stagnate at 58.3% (95%CI 55.7-60.9) for women vs. 63.1% (57.4-68.8) for men, while therapeutic inadequacy persists with only 22.7% (20.4-25.0) achieving guideline-recommended control targets[10].

Studies have consistently shown that risk factors for hypertension in women include, but are not limited to, overweight/obesity, exposure to cold environmental conditions, air pollution, high-sodium/low-potassium dietary patterns, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, chronic psychological stress, and physical inactivity. Notably, sex-based disparities are evident in salt-sensitive hypertension, underscoring the need for tailored preventive and therapeutic strategies. Additionally, hypertension in women is associated with race, comorbidities, socioeconomic status, education, and living environment[18,19]. Moreover, female-specific physiological factors such as menarche, menstrual cycle, pregnancy and perinatal periods, lactation, gestational diabetes, eclampsia, reproductive disorders and their management (assisted reproductive technology), menopause, oral contraceptive (OC) use, and hormone replacement therapy are linked to hypertension risk[1,2,19]. Multiple studies have confirmed that estrogen impacts BP by modulating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and endothelial system.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS

Multiple studies have shown that sex differences in BP regulation and vascular function between sexes arise from variations in the autonomic nervous system, RAAS, bradykinin, nitric oxide (NO), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), and sex-linked differences such as sex chromosomes, sex hormones, and other hormones. The autonomic nervous system plays a critical role in BP regulation, involving mechanisms such as genetics, neuroendocrine modulation, vascular function, renal vascular dynamics, metabolic abnormalities, and sex hormones[1,2,18]. Estrogen deficiency triggers sympathetic nervous system activation, increases endothelial adrenergic receptor expression and nitric oxide synthesis, and impairs vasodilation through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and salt sensitivity[1]. Sex-specific physiological differences are observed in the RAAS, where females exhibit elevated expression levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), angiotensin II type 2 receptor (AT2R), and Mas receptor. This indicates a more pronounced presence and activity of the vasodilatory and protective components of the RAAS in females[19]. Notably, the genes encoding both ACE2 and AT2R are situated on the X chromosome, implying that their expression could be modulated by factors related to sex chromosomes[19]. The female sex hormone potentiates the function of eNOS through both gene-expression-dependent and immediate signaling mechanisms. Investigations using fetal pulmonary artery endothelial cells from sheep demonstrated that the hormone-induced increase in both the abundance and functional capacity of this enzyme was completely abolished upon administration of a pure estrogen receptor antagonist, indicating that the mediation of this genomic upregulation is strictly dependent on the activation of estrogen receptors[20]. Data obtained from luciferase reporter assays further substantiated the role of estrogen response elements (EREs) in target gene promoters, indicating their likely involvement in mediating the transcriptional actions of estrogen. Regarding autonomic regulation, premenopausal women generally display lower sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) compared to men, a difference that diminishes after menopause[21,22]. Estrogen acts through its receptors-Estrogen Receptor alpha (ERα) and Estrogen Receptor beta (ERβ)-in critical brain regions to enhance baroreceptor reflex sensitivity (BRS) and reduce sympathetic outflow. Consequently, premenopausal women tend to have higher BRS and lower sympathetic activity compared to both postmenopausal women and men of similar age[19].

RAAS is believed to contribute to salt-sensitive hypertension in females[23,24]. It is especially after menopause that changes in renal sodium handling, oxidative stress, and hypertension occur[25]. Research involving normotensive women undergoing surgically induced menopause demonstrated that female sex hormones provide protection against salt sensitivity, an effect that occurs independently of the aging process. The decline in estrogen levels is believed to disrupt the regulatory balance of the RAAS and reduce the bioavailability of NO, which are key mechanisms contributing to the development of hypertension in postmenopausal women characterized by salt-sensitive BP[24,26]. Research by Faulkner et al. revealed that in females with salt-sensitive hypertension, the adrenal glands produce elevated levels of aldosterone compared to males, a phenomenon also observed in female animal models. This sex-specific increase is potentially modulated by the activation of the RAAS within the adrenal gland and the influence of receptors for sex hormones[27]. Estrogen also modulates calcium-dependent signaling pathways in vascular, renal, and cardiac cells, and enhances secretion of vasoconstrictors[2,18]. Moreover, findings by Kurniansyah et al. suggest that sex-specific differences in immune and inflammatory mechanisms play a role in the pathogenesis of hypertension among women[28].

Sex differences in hypertension depend on gene expression linked to sex chromosomes[29], while age-dependent sex differences in renal sodium transporter expression contribute to sex-specific BP regulation and diuretic responses[19]. A genetic analysis based on a large European database revealed stronger sex-dependent genetic predispositions in females[30]. Numerous investigations have detailed the influence of gonadal hormones on BP control mechanisms, yet the contribution of genetic sex determinants has received comparatively less attention, largely due to methodological constraints. Recent advances employing rodent models have facilitated the distinction between effects originating from gonadal type and those linked to the complement of sex chromosomes[19,31-33]. Ji et al.[34] demonstrated that male rodents displayed a more pronounced increase in arterial pressure following Ang II administration than females, an effect abolished by removal of gonads. A notable finding was that the Y chromosome was associated with a diminished pressor reaction to Ang II (approximately 14 mmHg), independent of gonadal status. Crucially, this investigation highlighted that genetic factors on the XX sex chromosome combination may play a role in the development of high BP in females following loss of ovarian function. Furthermore, clinical evidence indicates that paternal, but not maternal, hypertension is linked to elevated BP in normotensive sons[35].

Research indicates that compared to men, women with hypertension exhibit a higher prevalence of white coat hypertension and greater BP variability[36-38]. Healthy women demonstrate lower BRS and heart rate variability, while sympathetic nervous activity increases with aging and obesity in women[36-38]. A synthesis of evidence from 62 observational studies, encompassing a total of 196,989 women, demonstrated that employment involving rotating shifts was linked to elevated likelihoods of both preeclampsia and gestational hypertension when compared to individuals working a fixed daytime schedule[39].

Women generally have smaller arterial diameters, with multiple studies showing higher stiffness in female arteries, particularly in the ascending aorta[40,41], along with elevated vascular augmentation indices[42,43]. Age-related progression and hypertension lead to more pronounced increases in carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity and peripheral vascular resistance in women compared to men[41,43]. The progression of arterial stiffness exacerbates hemodynamic stress, leading to elastic fiber degradation and collagen deposition in arterial walls. This results in elevated SBP, widened pulse pressure, increased cardiac workload, left ventricular hypertrophy, and microvascular dysfunction in the cerebral and renal circulations[44].

A study by Ji et al. revealed that, compared to men, women exhibit an elevated risk of CVD at lower SBP thresholds. For equivalent SBP elevations, women face higher risks of CVD, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and stroke[45]. Specifically, women with SBP 100-119 mmHg showed increased risks of CVD, myocardial infarction, and heart failure compared to those with SBP < 100 mmHg, while men exhibited no significant increase. Female individuals exhibiting SBP levels between 110 and 119 mmHg demonstrated a myocardial infarction risk equivalent to that observed in males presenting with SBP readings of 160 mmHg or higher. Correspondingly, the likelihood of developing heart failure among these women with moderately elevated BP was analogous to the risk encountered in men whose systolic pressure fell within the

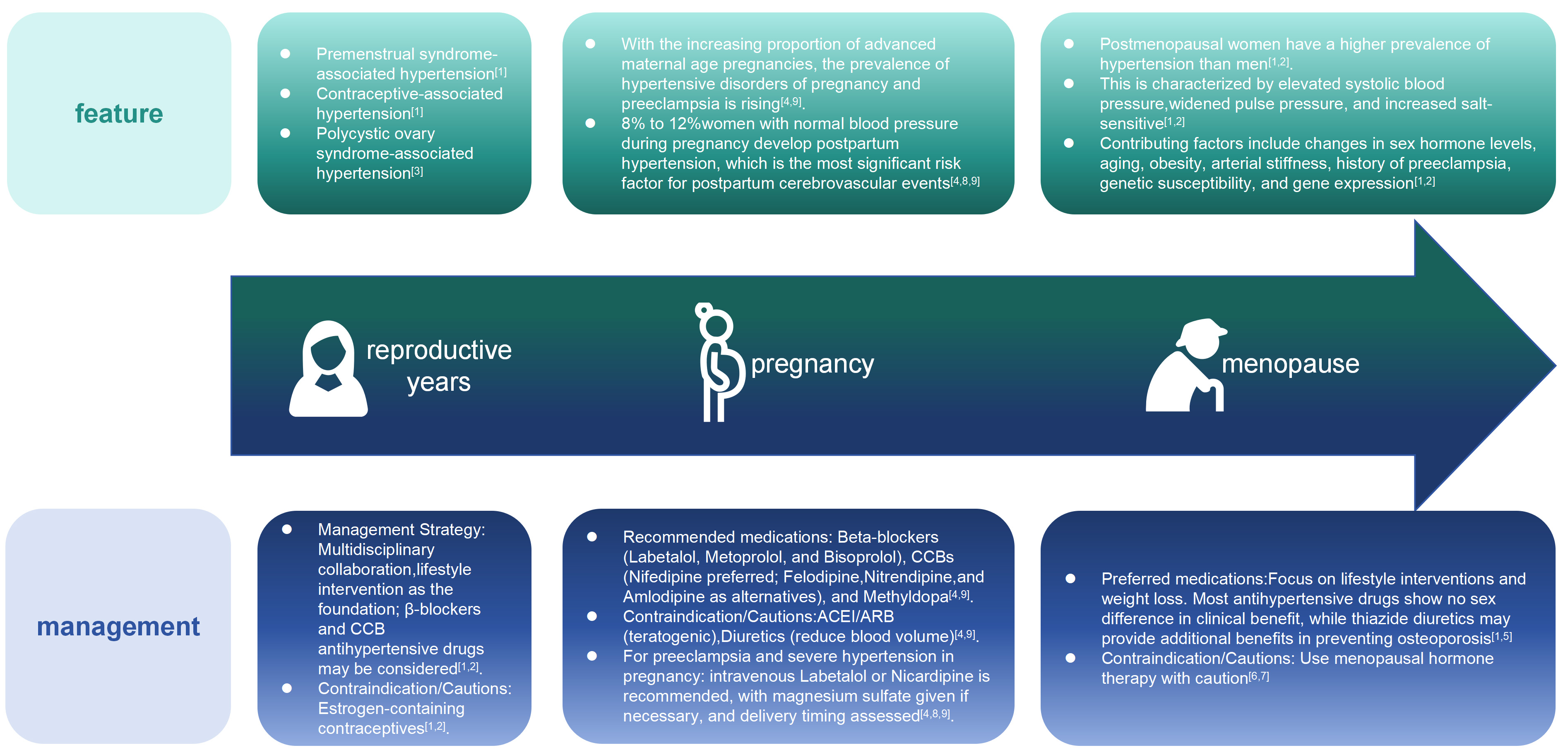

SPECIAL TYPES OF HYPERTENSION IN WOMEN

Premenstrual syndrome-related hypertension

BP in premenopausal women fluctuates with the menstrual cycle. During the luteal phase (1-10 days before menstruation), women may experience fatigue, irritability, and depression, as well as physical symptoms such as mild weight gain, edema, and mild elevation of BP 2-3 days before menstruation. Treatment primarily focuses on non-pharmacological interventions, including a light diet, appropriate exercise, and emotional regulation. If BP rises significantly, diuretics may be added 1-2 days before menstruation, during menstruation, and 1-2 days after menstruation[46].

Contraceptive pill-related hypertension

OCs consist of synthetic estrogen and progesterone. Estrogen-containing contraceptives may elevate BP by stimulating the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone, inducing water-sodium retention, increasing insulin resistance, angiotensinogen, aldosterone and catecholamine secretion[1,12]. BP typically normalizes

Polycystic ovary syndrome-related hypertension

Clinical manifestations include oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, infertility, and female masculinization. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is often associated with obesity, metabolic syndrome, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes. Elevated BP is primarily related to factors such as insulin resistance leading to sympathetic activation, endocrine disorders, increased cardiac output, and decreased vascular elasticity[3]. Treatment includes lifestyle modifications (such as a healthy diet, appropriate exercise, and scientific weight loss) and pharmacological interventions (such as metformin, finasteride, and aldosterone receptor antagonists)[3].

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDPs) include hypertension diagnosed before pregnancy or newly identified before 20 weeks of gestation, as well as hypertension developing after 20 weeks of gestation. HDPs represent a unique form of hypertension in women, with reported prevalence rates of 6%-10% in Europe and the United States and 5.22%-5.57% in China[9,47]. They threaten maternal and fetal health and are associated with increased long-term CVD risk in women[38]. Over the past decade, the prevalence of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia has risen by 25% due to increasing rates of advanced maternal age, with further growth anticipated in the future[48]. Approximately one-fifth to nearly one-third of women who experience hypertensive disorders in a first pregnancy are likely to develop hypertension again in a following pregnancy. Research indicates that an earlier gestational age at the time of delivery in the initial hypertensive pregnancy is associated with an increased likelihood of recurrence. To ensure accurate BP assessment and to distinguish between true hypertension and conditions such as white coat hypertension or masked hypertension during gestation, the utilization of self-measured home BP devices or 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring is recommended[5].

Despite extensive research, the etiology of HDPs remains unclear, with complex pathogenesis involving inflammatory responses, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and other pathological mechanisms[5]. Immune dysregulation plays a pivotal role in HDP development[49]. Preeclampsia poses severe risks to maternal and fetal health, including mortality, with key risk factors encompassing family history of preeclampsia, elevated body mass index (BMI), advanced maternal age in primiparas, and other multifactorial contributors[4,5].

The primary goals of treatment are to prevent severe preeclampsia and eclampsia, reduce maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality, and improve maternal and fetal outcomes. Timely delivery is a critical intervention for managing preeclampsia and eclampsia, with delivery recommended at 37 weeks of gestation, though high-risk cases may require earlier delivery. The International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP) advises maintaining BP within 110-140/80-85 mmHg for pregnant women with hypertension[4]. Antihypertensive medication is recommended for all pregnant individuals with confirmed BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg to reduce the risk of progression to severe hypertension and associated adverse pregnancy outcomes. Emergency scenarios, such as systolic BP ≥ 160 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 110 mmHg during pregnancy, warrant consideration for immediate hospitalization[4].

The 2024 European Society of Cardiology(ESC) Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension[5] recommended that women planning pregnancy should discontinue antihypertensive medications contraindicated during gestation at least six months prior to conception and transition to pregnancy-safe alternatives. Common oral antihypertensives for gestational hypertension include beta-blockers (e.g., labetalol, metoprolol, bisoprolol), dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (CCBs) such as nifedipine (preferred first-line recommendation), felodipine, nitrendipine, or amlodipine, and methyldopa. Meta-analyses indicate that beta-blockers and CCBs are more effective than methyldopa for severe hypertension, while hydralazine is also effective in severe cases[4,5,8]. Atenolol should be avoided due to risks of fetal intrauterine growth restriction, and methyldopa may cause adverse effects such as drowsiness or postpartum depression[4,5,8]. Nifedipine is contraindicated in women with tachycardia. For refractory hypertension, intravenous options include labetalol, urapidil, nicardipine, nimodipine, hydralazine, phentolamine, or nitroglycerin. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are strictly contraindicated due to teratogenic risks and oligohydramnios[4,5,8]. Diuretics are generally avoided during pregnancy to prevent hemoconcentration, reduced circulating blood volume, and hypercoagulability, though thiazide diuretics require cautious use due to limited safety data, while furosemide may be considered in specific clinical scenarios[4,5,8].

A sustained elevation in BP beyond 160 mmHg systolic or 110 mmHg diastolic during gestation is linked to negative health consequences for both the mother and the newborn, and these hazards exist irrespective of a concurrent diagnosis of preeclampsia[5]. Its potential harm may resemble that of eclampsia and often requires urgent antihypertensive treatment. While evidence for intravenous labetalol and hydralazine in BP control is conflicting, hydralazine may carry a higher risk of perinatal adverse events[4,5]. Nifedipine demonstrates superior antihypertensive efficacy compared to labetalol and is associated with lower rates of neonatal complications. Current recommendations prioritize intravenous labetalol, oral methyldopa, or oral nifedipine as first-line therapies for severe hypertension in pregnancy, with intravenous hydralazine reserved as a second-line option[4,5].

Postpartum hypertension

Elevated BP following childbirth affects a notable proportion of individuals who were normotensive during gestation, with estimates ranging from 8% to 12%. In contrast, more than half of those who experienced any form of HDP are found to have severe postpartum hypertension, defined by BP readings meeting or exceeding 150/100 mmHg[50,51]. Elevated BP represents the single most significant predictor for cerebrovascular events following childbirth, with a pronounced association with intracranial hemorrhage[52]. Studies show that the first 72 h postpartum represent the peak period for BP fluctuations, necessitating close monitoring, especially in women with HDP. BP should be measured within 6 h after delivery and at least once daily for the following week. Typically, BP in women with preeclampsia or obesity/overweight does not normalize within 7 days postpartum, often persisting for extended periods. Roughly one-quarter of individuals diagnosed with gestational hypertension necessitate ongoing pharmacological management for elevated BP for as long as two years following childbirth. Those with HDP should undergo 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring within 3 weeks postpartum and have BP reassessed at the 6-week postnatal follow-up[53].

For severe postpartum hypertension, particularly acute episodes accompanied by symptoms such as headache, chest pain, or shortness of breath, urgent treatment within 30-60 min is required. Intravenous agents (labetalol, hydralazine, or nicardipine) or oral CCBs are recommended for BP control[5]. According to the 2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Elevated Blood Pressure and Hypertension and the 2018 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases During Pregnancy, for patients with non-severe hypertension, antihypertensive medications that do not affect breastfeeding or have minimal transfer into breast milk are recommended. CCBs such as nifedipine, diltiazem, nicardipine, and verapamil, as well as β-blockers including labetalol, metoprolol, and propranolol, exhibit low levels in breast milk and are associated with rare adverse events in infants, making them preferred choices[5,54]. ACEIs (captopril, enalapril) show minimal milk transfer but may pose risks of neonatal hypotension, oliguria, or seizures. Diuretics (furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide, spironolactone) may reduce milk production and are not preferred for breastfeeding women. Hydralazine is considered acceptable for lactating mothers and neonates. Methyldopa, though safe for newborns, is associated with maternal depression and should be avoided; if used during pregnancy, switching to alternative medications within 2 days postpartum is advised[5,54].

Hypertension in postmenopausal women

After menopause, women lose the protective effects of estrogen, leading to an increased incidence of hypertension. The occurrence of high BP is more common in women after menopause than in men. Research indicates that these women are more likely to have a significant rise in their systolic pressure and a larger difference between their systolic and diastolic readings when compared to both younger women who are still menstruating and to men of a similar age[1,55], accompanied by significantly heightened cardiovascular risks associated with hypertension. While most research supports a link between menopause and hypertension, some studies show no significant difference in hypertension incidence before and after menopause after adjusting for age and body weight[56].

The mechanisms underlying menopause-related hypertension remain unclear. Beyond sex hormone fluctuations, contributing factors include aging, obesity, arterial stiffness, physical inactivity, preeclampsia history, genetic susceptibility, and altered gene expression[13,55]. Menopause-associated changes in estrogen and testosterone levels may drive pathophysiological processes that elevate BP, such as endothelial dysfunction, abnormal glucose/lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, activation of the sympathetic nervous system and RAAS, increased endothelin levels, reduced NO activity, heightened salt sensitivity, and elevated rates of weight gain and sleep apnea[13,57]. Additionally, menopause may activate hypertension-related genes, such as those with adrenergic receptor polymorphisms, further contributing to BP elevation. Some studies suggest that menopause-related BP increases correlate with weight gain and aging rather than ovarian estrogen deficiency[13].

The cardiovascular protective effects of menopause hormone therapy (MHT) in postmenopausal women remain controversial. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study demonstrated that MHT increases risks of coronary heart disease, stroke, and venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women, particularly in older women initiating therapy ≥ 10 years after menopause. Estrogen alone or combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate may elevate BP by 1-1.5 mmHg[58]. While some evidence suggests potential cardiovascular benefits of MHT in early postmenopausal women with hypertension, other studies show no significant impact on BP[6,7]. Due to its association with increased stroke risk, poorly controlled hypertension is a relative contraindication for MHT[6,7]. Compared to oral MHT, transdermal estrogen formulations carry a lower risk of hypertension, and certain progestogens (e.g., micronized progesterone, dydrogesterone, or drospirenone) may have neutral effects on BP[7,57].

Psychologically stress-induced hypertension

Psychologically stress-induced hypertension refers to elevated BP triggered by chronic stressors such as lifestyle or occupational pressures, where anxiety, depression, and other psychological factors contribute to treatment resistance[59]. Women exhibit a stronger correlation between elevated SBP and depressive symptoms compared to men[60]. Mechanisms underlying this condition involve dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, sympathetic nervous system hyperactivity, inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, genetic predisposition, and impaired NO modulation[61]. Due to hormonal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle, women may experience altered functional regulation in brain regions associated with emotional processing - such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex - which modulate neurohormonal stress responses and BP control[62]. Studies indicate that chronic stress, anxiety, depression, and exposure to traumatic life events elevate hypertension risk[63]. Young women aged 18-30 years face higher psychosocial burdens than men, with factors such as negative emotions, economic disadvantages, depression, and stress contributing to increased hypertension prevalence in this demographic[63,64]. Women are twice as likely as men to experience psychiatric disorders, and menopausal women are particularly prone to neurotic or depressive tendencies that may exacerbate BP elevation[65]. Diagnosis requires comprehensive evaluation, including medical history, psychological assessment, and attention to reproductive history (e.g., menstrual patterns, menopause status, contraceptive or estrogen use), alongside BP monitoring and stress-level evaluations.

Non-pharmacological interventions such as mindfulness-based therapy, stress-reduction training, meditation, and biofeedback are recommended for managing this condition[59,66]. For patients with comorbid anxiety or depression, combined antihypertensive and psychotropic medications (e.g., antianxiety or antidepressant drugs) may be considered under specialist guidance, alongside structured stress management and emotional regulation strategies to avoid anxiety-driven over-monitoring of BP. Notably, anxiety and depressive states impair both treatment efficacy and medication adherence in hypertensive patients[67].

Hypertension associated with female cancers

Multiple solid tumors can induce secondary hypertension, including juxtaglomerular cell tumors (reninomas), pheochromocytomas, and aldosterone-producing adrenal adenomas, some of which may be cured by surgical resection or ablation of the lesions[68,69]. A study by Inam et al. demonstrated that reninomas predominantly affect women, with a female-to-male prevalence ratio of approximately 2:1[70].

In women undergoing treatment for breast cancer, certain therapeutic regimens are correlated with an increased likelihood of developing high BP. Specifically, pharmacological agents administered prior to primary surgery, such as docetaxel, as well as hormonal treatments targeting estrogen-receptor positive malignancies - such as tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors (for instance, letrozole) - have been identified as contributors to a higher incidence of hypertension[71-74]. Additionally, left-sided breast cancer radiotherapy may contribute to hypertension development[74]. Medications designed to inhibit blood vessel formation in solid malignancies, including both antibody-based drugs (e.g., bevacizumab, ramucirumab) and orally administered kinase inhibitors (e.g., sunitinib, apatinib), are strongly associated with the development of high BP. For managing this particular form of hypertension, agents that target the RAAS - specifically ACEIs and ARBs - are advised as the initial therapeutic choice[75]. Clinical studies demonstrate that bevacizumab elevates hypertension risk in ovarian cancer treatment[76] and when combined with chemotherapy or endocrine therapy in breast cancer management[77-79].

SEX-SPECIFIC MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Globally, the prevention and control of hypertension among women remains suboptimal. Despite higher awareness rates among hypertensive women compared to men[80,81], women have lower BP control rates[82]. Elderly women exhibit even lower control rates than younger and middle-aged women[12], potentially linked to factors such as depression and socioeconomic disparities[83-85]. Compared to men, hypertensive women face higher probabilities of target organ damage (e.g., atrial fibrillation, left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure, and stroke) and greater mortality risk, with CVD-related deaths accounting for 44.33% of total female deaths vs. 38.24% in males.

Adopting a healthy lifestyle is a foundational therapeutic approach for hypertension, effectively lowering BP, reducing cardiovascular events, and decreasing reliance on antihypertensive medications[86,87]. Dietary sodium intake is strongly associated with hypertension, and reducing salt consumption helps lower BP[88]. A daily sodium chloride (salt) intake of less than 5 grams is recommended. While strict sodium restriction during pregnancy may lower BP, studies suggest it could reduce blood volume and adversely affect fetal development, necessitating moderate sodium restriction in this population[8]. Postmenopausal women are more prone to obesity, and weight management helps prevent and manage hypertension. For pregnant, lactating, and elderly women, personalized weight management strategies should be implemented. Smoking poses greater cardiovascular risks for women than men, and hypertensive patients are strongly advised to quit smoking. Excessive alcohol consumption elevates hypertension risk and contributes to resistant hypertension. Women with hypertension are advised to abstain from alcohol. Women are more inclined to face dual pressures from work and life, increasing susceptibility to stress-, anxiety-, and depression-related hypertension. Stress management techniques such as mindfulness practices, Tai Chi, and yoga are recommended to stabilize emotions and maintain mental well-being[89].

While most antihypertensives show no significant sex-based differences in therapeutic benefits, women experience a higher incidence of adverse drug reactions. Most antihypertensive medications demonstrate comparable therapeutic benefits across genders. However, studies suggest that thiazide diuretics, by reducing urinary calcium excretion and potentially preventing osteoporosis, may provide additional advantages for elderly female hypertensive patients[13,90].

RDN, which reduces sympathetic nervous system overactivity by modulating afferent/efferent renal nerves and neuroendocrine axes, may be considered for refractory hypertension cases. However, it currently lacks robust clinical evidence for long-term efficacy and has limited data on sex-specific outcomes.

PHARMACOKINETIC AND PHARMODYNAMIC DIFFERENCES OF ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUGS BETWEEN SEXES

Pharmacokinetic variations between sexes stem from dissimilarities in body composition, the process of drug absorption, distribution within plasma and tissues, the activity of metabolizing enzymes and transporters, as well as drug elimination processes[84,91-98]. Females typically exhibit reduced gastric acid production and longer gastrointestinal transit durations, although intestinal metabolism does not show a consistent pattern of variation by sex[97-100]. Prolonged gastrointestinal transit can decrease the absorption of metoprolol or verapamil, and drugs requiring an acidic environment for absorption may have lower oral bioavailability in women. They should wait longer after eating before taking drugs that need to be administered on an empty stomach[84,98].

Compared to males, females generally possess a greater proportion of body fat, along with lower overall body weight, plasma volume, organ dimensions, and blood flow rates. These physiological differences account for the more rapid onset of action, larger volume of distribution (Vd), and prolonged duration of effect observed for lipophilic drugs in women. Conversely, hydrophilic drugs exhibit a smaller Vd in females, leading to elevated peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) and more pronounced pharmacological effects[84,100-102].

Sex hormones can engage with enzymes that facilitate drug absorption and metabolism, potentially altering both the therapeutic effectiveness and the severity of adverse drug responses. In particular, estrogen and progesterone are known to downregulate the expression of cardiac β1-adrenergic receptors, thereby offering a protective effect on the heart[2]. Women tend to show higher Cmax and area under the curve (AUC) for metoprolol and propranolol, which results from increased absorption rates, a reduced Vd, and diminished clearance mediated by Cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6). This culminates in a more substantial decrease in heart rate and SBP following physical exertion[103-105]. The concurrent use of OCs has been shown to result in significantly higher systemic concentrations of metoprolol[103]. Conversely, in male individuals, testosterone appears to upregulate the expression of the CYP2D6 enzyme, which is responsible for the drug's metabolism, potentially accelerating its elimination from the body[103].

A sex-dependent divergence in pharmacokinetics is observed based on the route of administration. For nifedipine and verapamil, intravenous infusion leads to accelerated clearance and diminished plasma concentrations in females. However, when these agents are administered orally, females demonstrate a slower clearance compared to their male counterparts[106,107]. This difference could be explained by a combination of factors, including a smaller overall body size, enhanced activity of the cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme system, and/or reduced function of the P-glycoprotein efflux transporter when compared to males[108]. The clearance of verapamil tends to decline with advancing age in women, accounting for the enhanced antihypertensive reaction observed in older female patients[109]. In general, women are more susceptible to adverse effects from antihypertensive drugs compared to men, although this trend does not extend to mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. Specifically, women are more prone to hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and arrhythmias during diuretic therapy; to edema when using dihydropyridine CCBs; and to cough when using ACEIs. In contrast, men are more inclined to experience gout as a side effect of diuretic treatment[2,110,111].

CONCLUSION

Hypertension management in women demands a sex-specific approach informed by distinct biological, hormonal, and psychosocial factors. Across the lifespan - from pregnancy to menopause - women face unique challenges: HDPs elevate long-term cardiovascular risks, menopausal hormonal shifts accelerate arterial stiffness, and older women exhibit higher rates of obesity-related and resistant hypertension. Current guidelines, largely derived from male-centric studies, inadequately address these nuances, leading to delayed diagnoses and suboptimal treatment outcomes. Emerging evidence highlights differential drug responses, with women experiencing greater adverse effects (e.g., ACEI-induced cough) but potential benefits from tailored therapies such as thiazides for osteoporosis prevention. Psychosocial stressors, including depression and socioeconomic disparities, further complicate management, necessitating integrated lifestyle interventions. Future priorities include expanding sex-stratified research on novel therapies, clarifying risks of hormone replacement, and refining diagnostic tools to detect sex-specific phenotypes. Multidisciplinary collaboration - spanning cardiology, endocrinology, and psychiatry - is critical to developing life-course management strategies. By embedding sex-specific insights into guidelines and prioritizing female representation in trials, healthcare systems can mitigate disparities and improve cardiovascular outcomes for women globally.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Drafting, searching the literature, creating figures, and editing the review: Zhuge R

Constructing and reviewing the content for accuracy: Liu M

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

The work was supported by Project 2019BD019 of the PKU-Baidu Fund.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Wenger NK, Arnold A, Bairey Merz CN, et al. Hypertension across a woman's life cycle. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1797-813.

2. Gerdts E, Sudano I, Brouwers S, et al. Sex differences in arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:4777-88.

3. Macut D, Mladenović V, Bjekić-Macut J, et al. Hypertension in polycystic ovary syndrome: novel insights. Curr Hypertens Rev. 2020;16:55-60.

4. Brown MA, Magee LA, Kenny LC, et al. The hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: ISSHP classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018;13:291-310.

5. McEvoy JW, McCarthy CP, Bruno RM, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension: developed by the task force on the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and endorsed by the European Society of Endocrinology (ESE) and the European Stroke Organisation (ESO). Eur Heart J. 2024;45:3912-4018.

6. Cho L, Kaunitz AM, Faubion SS, et al. Rethinking menopausal hormone therapy: for whom, what, when, and how long? Circulation. 2023;147:597-610.

7. Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, et al. Hormone therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal persons: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;328:1740-6.

8. Heart Health Group of Chinese Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association; Hypertension Group of Chinese Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association. Expert consensus on blood pressure management in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (2019). Chin J Cardiol. 2020;48:10.

9. Umesawa M, Kobashi G. Epidemiology of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: prevalence, risk factors, predictors and prognosis. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:213-20.

10. Kario K, Okura A, Hoshide S, Mogi M. The WHO Global report 2023 on hypertension warning the emerging hypertension burden in globe and its treatment strategy. Hypertens Res. 2024;47:1099-102.

11. Zhou B, Perel P, Mensah GA, Ezzati M. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18:785-802.

12. Ghazi L, Annabathula RV, Bello NA, Zhou L, Stacey RB, Upadhya B. Hypertension across a woman's life cycle. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2022;24:723-33.

13. Chapman N, Ching SM, Konradi AO, et al. Arterial hypertension in women: state of the art and knowledge gaps. Hypertension. 2023;80:1140-9.

14. Ji H, Kim A, Ebinger JE, et al. Sex differences in blood pressure trajectories over the life course. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:19-26.

15. Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, et al. Status of hypertension in China: results from the China hypertension survey, 2012-2015. Circulation. 2018;137:2344-56.

16. Tao S, Wu X, Duan X, et al. Hypertension prevalence and status of awareness, treatment and control in China. Chin Med J. 1995;108:483-9.

17. Xia S, Du X, Guo L, et al. Sex Differences in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in China. Circulation. 2020;141:530-9.

18. Gerdts E, Regitz-Zagrosek V. Sex differences in cardiometabolic disorders. Nat Med. 2019;25:1657-66.

19. Drury ER, Wu J, Gigliotti JC, Le TH. Sex differences in blood pressure regulation and hypertension: renal, hemodynamic, and hormonal mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2024;104:199-251.

20. MacRitchie AN, Jun SS, Chen Z, et al. Estrogen upregulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene expression in fetal pulmonary artery endothelium. Circ Res. 1997;81:355-62.

21. Ng AV, Callister R, Johnson DG, Seals DR. Age and gender influence muscle sympathetic nerve activity at rest in healthy humans. Hypertension. 1993;21:498-503.

22. Weitz G, Elam M, Born J, Fehm HL, Dodt C. Postmenopausal estrogen administration suppresses muscle sympathetic nerve activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:344-8.

23. White CR, Shelton J, Chen SJ, et al. Estrogen restores endothelial cell function in an experimental model of vascular injury. Circulation. 1997;96:1624-30.

24. Pilic L, Pedlar CR, Mavrommatis Y. Salt-sensitive hypertension: mechanisms and effects of dietary and other lifestyle factors. Nutr Rev. 2016;74:645-58.

25. Schulman I, Raij L. Salt sensitivity and hypertension after menopause: role of nitric oxide and angiotensin II. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26:170-80.

26. Schulman IH, Aranda P, Raij L, Veronesi M, Aranda FJ, Martin R. Surgical menopause increases salt sensitivity of blood pressure. Hypertension. 2006;47:1168-74.

27. Faulkner JL, Belin de Chantemèle EJ. Female sex, a major risk factor for salt-sensitive hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2020;22:99.

28. Kurniansyah N, Goodman MO, Kelly TN, et al. A multi-ethnic polygenic risk score is associated with hypertension prevalence and progression throughout adulthood. Nat Commun. 2022;13:3549.

29. Colafella KMM, Denton KM. Sex-specific differences in hypertension and associated cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14:185-201.

30. Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, et al. The UK biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562:203-9.

31. Sampson AK, Jennings GL, Chin-Dusting JP. Y are males so difficult to understand?: a case where “X” does not mark the spot. Hypertension. 2012;59:525-31.

32. Khan SI, Andrews KL, Jennings GL, Sampson AK, Chin-Dusting JPF. Y chromosome, hypertension and cardiovascular disease: is inflammation the answer? Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2892.

33. Arnold AP. Four core genotypes and XY* mouse models: update on impact on SABV research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;119:1-8.

34. Ji H, Zheng W, Wu X, et al. Sex chromosome effects unmasked in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:1275-82.

35. Charchar FJ, Tomaszewski M, Padmanabhan S, et al. The Y chromosome effect on blood pressure in two European populations. Hypertension. 2002;39:353-6.

36. Hamidovic A, Van Hedger K, Choi SH, Flowers S, Wardle M, Childs E. Quantitative meta-analysis of heart rate variability finds reduced parasympathetic cardiac tone in women compared to men during laboratory-based social stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;114:194-200.

37. Philbois SV, Facioli TP, Gastaldi AC, et al. Important differences between hypertensive middle-aged women and men in cardiovascular autonomic control-a critical appraisal. Biol Sex Differ. 2021;12:11.

38. Sevre K, Lefrandt JD, Nordby G, et al. Autonomic function in hypertensive and normotensive subjects: the importance of gender. Hypertension. 2001;37:1351-6.

39. Cai C, Vandermeer B, Khurana R, et al. The impact of occupational shift work and working hours during pregnancy on health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:563-76.

40. Coutinho T, Borlaug BA, Pellikka PA, Turner ST, Kullo IJ. Sex differences in arterial stiffness and ventricular-arterial interactions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:96-103.

41. Campos-Arias D, De Buyzere ML, Chirinos JA, Rietzschel ER, Segers P. Longitudinal changes of input impedance, pulse wave velocity, and wave reflection in a middle-aged population: the asklepios study. Hypertension. 2021;77:1154-65.

42. McEniery CM, Yasmin

43. Nardin C, Maki-Petaja KM, Miles KL, et al. Cardiovascular phenotype of elevated blood pressure differs markedly between young males and females: the Enigma study. Hypertension. 2018;72:1277-84.

44. Mitchell GF. Aortic stiffness, pressure and flow pulsatility, and target organ damage. J Appl Physiol. 2018;125:1871-80.

45. Ji H, Niiranen TJ, Rader F, et al. Sex differences in blood pressure associations with cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2021;143:761-3.

46. Society of Cardiology, Chinese Medical Association; Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. [Expert consensus on the management of hypertension in women]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2025;53:872-81.

47. Gillon TE, Pels A, von Dadelszen P, MacDonell K, Magee LA. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review of international clinical practice guidelines. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113715.

48. Shan D, Qiu PY, Wu YX, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women of advanced maternal age: a retrospective Cohort study from China. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12239.

49. Jafri S, Ormiston ML. Immune regulation of systemic hypertension, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and preeclampsia: shared disease mechanisms and translational opportunities. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2017;313:R693-705.

50. Ngene NC, Moodley J. Postpartum blood pressure patterns in severe preeclampsia and normotensive pregnant women following abdominal deliveries: a cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:3152-62.

51. Goel A, Maski MR, Bajracharya S, et al. Epidemiology and mechanisms of de novo and persistent hypertension in the postpartum period. Circulation. 2015;132:1726-33.

52. Wu P, Jordan KP, Chew-Graham CA, et al. Temporal trends in pregnancy-associated stroke and its outcomes among women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e016182.

53. Graves M, Howse K, Pudwell J, et al. Pregnancy-related cardiovascular risk indicators: primary care approach to postpartum management and prevention of future disease. Can Fam Phys. 2019;65:883-9.

54. Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, et al. 2018 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the task force for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3165-241.

55. Cho L, Davis M, Elgendy I, et al. Summary of updated recommendations for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2602-18.

56. Casiglia E, d'Este D, Ginocchio G, et al. Lack of influence of menopause on blood pressure and cardiovascular risk profile: a 16-year longitudinal study concerning a cohort of 568 women. J Hypertens. 1996;14:729-36.

57. El Khoudary SR, Aggarwal B, Beckie TM, et al. Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: implications for timing of early prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e506-32.

58. Manson JE, Hsia J, Johnson KC, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:523-34.

59. Nejati S, Zahiroddin A, Afrookhteh G, et al. Effect of group mindfulness-based stress-reduction program and conscious yoga on lifestyle, coping strategies, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures in patients with hypertension. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2015;10:140-8.

60. Räikkönen K, Matthews KA, Kuller LH. Trajectory of psychological risk and incident hypertension in middle-aged women. Hypertension. 2001;38:798-802.

61. Regitz-Zagrosek V, Gebhard C. Gender medicine: effects of sex and gender on cardiovascular disease manifestation and outcomes. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20:236-47.

62. Vaccarino V, Wilmot K, Al Mheid I, et al. Sex differences in mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016:5.

63. Mendlowicz V, Garcia-Rosa ML, Gekker M, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder as a predictor for incident hypertension: a 3-year retrospective cohort study. Psychol Med. 2023;53:132-9.

64. Fiechter M, Roggo A, Burger IA, et al. Association between resting amygdalar activity and abnormal cardiac function in women and men: a retrospective cohort study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20:625-32.

65. Steiner M, Dunn E, Born L. Hormones and mood: from menarche to menopause and beyond. J Affect Disord. 2003;74:67-83.

66. Charchar FJ, Prestes PR, Mills C, et al. Lifestyle management of hypertension: International Society of Hypertension position paper endorsed by the World Hypertension League and European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2024;42:23-49.

67. Bautista LE, Vera-Cala LM, Colombo C, Smith P. Symptoms of depression and anxiety and adherence to antihypertensive medication. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:505-11.

68. Phillis C, Midenberg E, O'Connor M, Terry W Jr, Keel C, Noh P. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor: a rare presentation of a surgically curable cause of secondary hypertension in the pediatric population. Urology. 2021;156:e131-3.

69. Maiolino G, Battistel M, Barbiero G, Bisogni V, Rossi GP. Cure with cryoablation of arterial hypertension due to a renin-producing tumor. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:537-40.

70. Inam R, Gandhi J, Joshi G, Smith NL, Khan SA. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor: reviewing a cryptic cause of surgically correctable hypertension. Curr Urol. 2019;13:7-12.

71. Szczepaniak P, Siedlinski M, Hodorowicz-Zaniewska D, et al. Breast cancer chemotherapy induces vascular dysfunction and hypertension through a NOX4-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2022;132:e149117.

72. Rillamas-Sun E, Kwan ML, Iribarren C, et al. Development of cardiometabolic risk factors following endocrine therapy in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2023;201:117-26.

73. Colleoni M, Luo W, Karlsson P, et al. Extended adjuvant intermittent letrozole versus continuous letrozole in postmenopausal women with breast cancer (SOLE): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:127-38.

74. Kwan ML, Cheng RK, Iribarren C, et al. Risk of cardiometabolic risk factors in women with and without a history of breast cancer: the pathways heart study. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:1635-46.

75. Dong M, Wang R, Sun P, et al. Clinical significance of hypertension in patients with different types of cancer treated with antiangiogenic drugs. Oncol Lett. 2021;21:315.

76. Gamble CR, Chen L, Szamreta E, Monberg M, Hershman D, Wright J. Patterns of use and outcomes of adjuvant bevacizumab therapy prior to regulatory approval in women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;305:1647-54.

77. Cameron D, Brown J, Dent R, et al. Adjuvant bevacizumab-containing therapy in triple-negative breast cancer (BEATRICE): primary results of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:933-42.

78. Dickler MN, Barry WT, Cirrincione CT, et al. Phase III trial evaluating letrozole as first-line endocrine therapy with or without bevacizumab for the treatment of postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive advanced-stage breast cancer: CALGB 40503 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2602-9.

79. Cuppone F, Bria E, Vaccaro V, et al. Magnitude of risks and benefits of the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer patients: meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:54.

80. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6-e245.

81. Lloyd-Sherlock P, Beard J, Minicuci N, Ebrahim S, Chatterji S. Hypertension among older adults in low- and middle-income countries: prevalence, awareness and control. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:116-28.

82. Osude N, Durazo-Arvizu R, Markossian T, et al. Age and sex disparities in hypertension control: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Prev Cardiol. 2021;8:100230.

83. Holt E, Joyce C, Dornelles A, et al. Sex differences in barriers to antihypertensive medication adherence: findings from the cohort study of medication adherence among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:558-64.

84. Tamargo J, Rosano G, Walther T, et al. Gender differences in the effects of cardiovascular drugs. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2017;3:163-82.

86. Valenzuela PL, Carrera-Bastos P, Gálvez BG, et al. Lifestyle interventions for the prevention and treatment of hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18:251-75.

87. Hinderliter AL, Smith P, Sherwood A, Blumenthal J. Lifestyle interventions reduce the need for guideline-directed antihypertensive medication. Am J Hypertens. 2021;34:1100-7.

88. Filippini T, Malavolti M, Whelton PK, Naska A, Orsini N, Vinceti M. Blood pressure effects of sodium reduction: dose-response meta-analysis of experimental studies. Circulation. 2021;143:1542-67.

89. Rainforth MV, Schneider RH, Nidich SI, Gaylord-King C, Salerno JW, Anderson JW. Stress reduction programs in patients with elevated blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2007;9:520-8.

90. Smith JR, Thomas RJ, Bonikowske AR, Hammer SM, Olson TP. Sex Differences in cardiac rehabilitation outcomes. Circ Res. 2022;130:552-65.

91. Jochmann N, Stangl K, Garbe E, Baumann G, Stangl V. Female-specific aspects in the pharmacotherapy of chronic cardiovascular diseases. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1585-95.

92. Rosano GM, Lewis B, Agewall S, et al. Gender differences in the effect of cardiovascular drugs: a position document of the Working Group on Pharmacology and Drug Therapy of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2677-80.

93. Kashuba AD, Nafziger AN. Physiological changes during the menstrual cycle and their effects on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1998;34:203-18.

94. Farkouh A, Riedl T, Gottardi R, Czejka M, Kautzky-Willer A. Sex-related differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of frequently prescribed drugs: a review of the literature. Adv Ther. 2020;37:644-55.

95. Soldin OP, Mattison DR. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48:143-57.

96. Gandhi M, Aweeka F, Greenblatt RM, Blaschke TF. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:499-523.

97. Franconi F, Campesi I. Pharmacogenomics, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: interaction with biological differences between men and women. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:580-94.

98. Stolarz AJ, Rusch NJ. Gender differences in cardiovascular drugs. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2015;29:403-10.

99. Freire AC, Basit AW, Choudhary R, Piong CW, Merchant HA. Does sex matter? The influence of gender on gastrointestinal physiology and drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2011;415:15-28.

100. Nicolas JM, Espie P, Molimard M. Gender and interindividual variability in pharmacokinetics. Drug Metab Rev. 2009;41:408-21.

101. Anderson GD. Sex and racial differences in pharmacological response: where is the evidence? Pharmacogenetics, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. J Womens Health. 2005;14:19-29.

102. Meibohm B, Beierle I, Derendorf H. How important are gender differences in pharmacokinetics? Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41:329-42.

103. Luzier AB, Killian A, Wilton JH, Wilson MF, Forrest A, Kazierad DJ. Gender-related effects on metoprolol pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;66:594-601.

104. Walle T, Walle UK, Cowart TD, Conradi EC. Pathway-selective sex differences in the metabolic clearance of propranolol in human subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1989;46:257-63.

105. Walle T, Byington RP, Furberg CD, McIntyre KM, Vokonas PS. Biologic determinants of propranolol disposition: results from 1308 patients in the Beta-Blocker Heart Attack Trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1985;38:509-18.

106. Krecic-Shepard ME, Park K, Barnas C, Slimko J, Kerwin DR, Schwartz JB. Race and sex influence clearance of nifedipine: results of a population study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68:130-42.

107. Krecic-Shepard ME, Barnas CR, Slimko J, Schwartz JB. Faster clearance of sustained release verapamil in men versus women: continuing observations on sex-specific differences after oral administration of verapamil. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68:286-92.

108. Dadashzadeh S, Javadian B, Sadeghian S. The effect of gender on the pharmacokinetics of verapamil and norverapamil in human. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2006;27:329-34.

110. Kajiwara A, Saruwatari J, Kita A, et al. Younger females are at greater risk of vasodilation-related adverse symptoms caused by dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers: results of a study of 11,918 Japanese patients. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34:431-5.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].