Coronary artery bypass grafting in women: a review of literature

Abstract

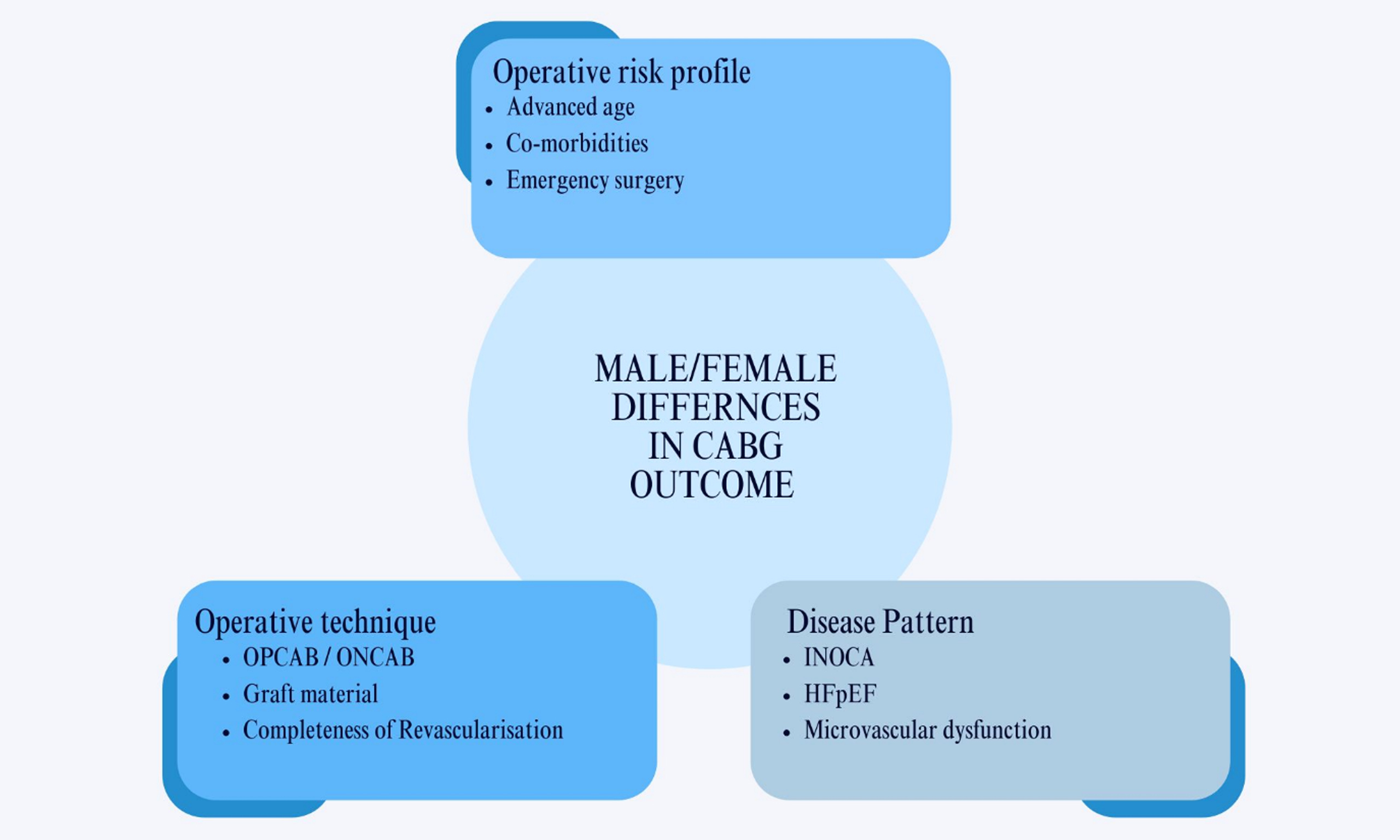

The role of sex in coronary artery disease (CAD), including its treatment and prognosis, is complex and has been studied for several decades. It is well known that men and women differ physiologically and that the pathophysiology of CAD varies between sexes. Additionally, there are sex differences in outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), with women experiencing worse outcomes than men. A PubMed search was conducted using terms related to differences between men and women with CAD requiring CABG. We will discuss the status of CABG in women with respect to preoperative profile, surgical strategy, short- and long-term outcomes, and quality of life. The leading causes of these differences remain debated. Generally, women are older and have a greater clustering of risk factors at the time of CABG. In particular, short-term outcomes appear worse for women, while studies on long-term outcomes are contradictory. Women also report a worse quality of life after CABG and experience higher rates of depression.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) was the second most common cause of death in the Netherlands in the year 2023. Coronary artery disease (CAD) accounted for 21% of all cardiovascular deaths[1]. The pathophysiology of CAD is complex and is currently viewed as an inflammatory disorder. Atherogenesis involves a complex interaction of risk factors, including cells of the arterial wall and blood, as well as the molecular signals they exchange[2]. Treatment for CAD depends on the severity of the disease and can vary between medical treatment, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)[3]. The role of sex in CAD, including its treatment and prognosis, is complex and has been studied for several decades. There are sex differences in outcomes after PCI and CABG, although the contribution of

CAD is still presumed as a predominantly male disease with a major focus on obstructive CAD. As women more often have non-obstructive CAD and coronary vascular dysfunction, treating CAD in women is considered more challenging[8]. A recent literature review on cardiac surgery in women concluded that they present later in the disease course, receive less aggressive treatment, and have more residual disease and lower quality of life after surgery. In addition, the authors address sex disparities in both basic and clinical research[9]. Therefore, various treatments are applied with possibly suboptimal results. Mansur et al. compared CAD treatments in men and women and found similar outcomes for CABG and PCI in female patients with stable multivessel CAD compared with medical therapy, emphasizing the need for equal treatment strategies for men and women with stable multivessel CAD[10].

In this literature review, we discuss CABG in women and the differences in preoperative profile, surgical strategy, and short- and long-term outcomes.

ANATOMICAL-, PHYSIOLOGICAL- AND PREOPERATIVE RISK FACTOR DIFFERENCES

Female hearts are smaller, lighter, have a smaller left ventricular (LV) diameter, and have narrower calibers of coronary arteries compared to male hearts[11-14]. Women with CAD generally have a higher LV ejection fraction[15]. These structural differences are related to a generally lower body surface area (BSA) in women. This does not necessarily imply that, due to smaller coronary artery caliber, female patients are more prone to CAD. Obstructive CAD remains more common in men[16]. Women are more likely to suffer from coronary artery dysfunction and non-obstructive CAD, and therefore more frequently experience recurrent or residual anginal symptoms after intervention for obstructive CAD[8].

Estrogen is thought to have a protective effect on the arterial wall. It affects and transduces signals to genes that are abundant in vascular tissue and therefore regulates the expression of these genes. Variations in plasma sex hormones and in genes responsive to these hormones affect vascular smooth muscle cells; therefore, sex hormones are related to functional and structural differences both between women and between men and women. The effects of sex hormones on processes such as remodeling, vasodilatation, platelet aggregation, thrombogenesis, endothelial function, and lipid metabolism influence the manifestation of CAD in female patients in a positive way[12,17]. These protective effects are generally present in women with normal estrogen production up to menopause. The transition is associated with abnormal endothelial function, specifically in the coronary microvasculature. After menopause, the protective effects of sex hormones diminish, and the risk of developing both non-obstructive and obstructive CAD increases over time. In general, women over 65 years still develop obstructive CAD less frequently than men[12].

In addition to traditional CAD risk factors, which are more prevalent in women over 65 years compared with men of similar age, women also carry sex-specific risk factors. These include polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis, hypertensive pregnancy disorders, early (natural) menopause, and prior treatment with radiotherapy or chemotherapy for breast cancer. Such risk factors may predispose women to metabolic disturbances, chronic inflammation, and premature hypertension[12,17,18].

Other conditions unique to women are linked to pregnancy and the peripartum period. These include hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (e.g., preeclampsia and eclampsia), gestational diabetes, and an increased risk of coronary or aortic root dissection during pregnancy. Female vessels normally undergo physiological remodeling during and after pregnancy. However, the peripartum conditions mentioned above are associated with pregnancy-related hypertension, which makes the remodeling pathological and linked to various cardiovascular problems[19].

In women with CAD, the disease burden is often different, and sometimes perceived as lower, than in men. Women more often have isolated left main or single-vessel disease, whereas men more often present with multivessel disease[20-22]. Microvascular disease or angina without flow-limiting epicardial lesions is seen more frequently in women, Ischemia with non-obstructive CAD (INOCA) is also more frequently seen in women. When INOCA occurs, a mismatch is seen between oxygen supply and oxygen demand from the myocardium. This mismatch, when CAD is absent, can be caused by coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) or epicardial coronary artery spasm. Studies have shown that among female patients who are referred for coronary angiography, between 50%-70% do not have obstructive CAD, while this percentage is 30%-50% in men[8]. CMD is not an innocent pathology. It appears to be present in 75% to 81% of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) patients and might even be one of the treatable causes of HFpEF[23,24]. In the study conducted by Nguyen et al., HFpEF was associated with higher in-hospital mortality after all types of cardiothoracic surgery[25]. Women are twice as likely to suffer from HFpEF compared to men[26]. Whether CMD plays a role in this difference in incidence remains to be discovered.

Anginal symptoms in women are often considered “atypical”, and these are thought to be the symptoms with which women with CAD most frequently present[27].

A meta-analysis of four large trials showed that among 13,193 patients, including 2,714 women, female patients were older, more symptomatic, and had a higher prevalence of comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, a history of congestive heart failure, and previous stroke[28,29]. These findings are consistent with what is generally described regarding the preoperative risk profile in women. Men more often had a history of myocardial infarction (MI) and were more likely to be smokers[30-34]. Women generally have better left ventricular function, but they present with a higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) class and lower functional capacity preoperatively. The onset of CAD in women typically lags behind men by nearly a decade[35].

Certain traditional risk factors for CVD are more common in younger men than in younger women. However, as a population ages, the typical CVD risk factors mentioned above become more common in women[36]. Young women with CAD might have suffered from peripartum or sex-related risk factors.

Some of the more traditional risk factors weigh differently for men and women. Obesity, for example, increases coronary risk by 64% in women and 46% in men[37]. Neither obesity nor having a lower BSA benefits women. Campbell et al. found that among patients with a small BSA (< 1.8 m2), female patients fared worse than male patients with the same BSA[38]. Diabetes also has a greater adverse impact on women. Wang et al. found that the pooled relative risk of CVD mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus was 2.42 in women [95% confidence interval (CI): 2.10-2.78] and 1.86 in men (95%CI: 1.70-2.03)[39]. Koch et al. examined sex differences in preoperative risk factors and found that conditions such as congestive heart failure, anemia, or a history of MI were associated with a higher risk of mortality after CABG in women than in men[34-40].

PERIOPERATIVE DIFFERENCES

A difference in perioperative care between men and women has been described and might, partially, explain differences in outcomes. Clayton et al. found that when patients present with unstable angina or (Non)

DIFFERENCES IN SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Studies have shown that a difference in surgical technique exists between male and female patients[42]. These differences include (in)complete revascularization, the type of conduit used, and the use of on- or off-pump surgery. The importance of complete revascularization has been extensively described. It reduces postoperative ischemia, arrhythmias, and heart failure, and leads to improved LV function and preserved ejection fraction. Additionally, complete revascularization decreases mortality, MI, and the need for repeat revascularization procedures[42,43]. Despite the well-known effects of complete revascularization, it seems that women still receive relatively fewer grafts compared to men[44]. Even after adjustment for the severity of CAD, women still received significantly fewer grafts (2.55 ± 0.9 vs. 2.88 ± 0.9, P = 0.013)[19]. One study, which examined the completeness of revascularization among both sexes, revealed that in double vessel disease, women were more frequently incompletely vascularized (7% female vs. 2% male, P < 0.001)[45]. The study by Burgess et al. investigated the burden of incomplete revascularization in women and men among 633

TYPE OF GRAFTS AND CONDUITS

In addition to receiving fewer grafts, it seems that the selection of the type of conduit is also different for women and men[47]. Women receive fewer arterial grafts than men. This has been described for all sorts of arterial grafts such as left and right internal mammary artery (LIMA and RIMA) and the radial artery, as well as the combinations of these types of grafts[48,49]. Contrary to this, in a more recent national database study of UK patients undergoing CABG, females received more total arterial grafts as compared to men[50]. These anomalous results may be explained by the fact that women in this study were approximately the same age as men, whereas women are typically much older when they undergo surgery for CAD.

The benefits of using an internal mammary artery (IMA) graft as the first graft to the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery were discovered in 1986 and have since been extensively described. This has been attributed to the graft’s excellent patency rate[51]. Several studies have demonstrated a reduced use of IMAs in female patients, which could worsen long-term outcomes for female patients. However, a large meta-analysis by Gaudino et al. demonstrated, using propensity matching, that the use of multiple arterial grafts (MAG) was associated with a reduction in major adverse cardiovascular and cerebral event (MACCE) in men, an effect that was not seen in women[52]. Therefore, the question remains whether the known benefits of using arterial grafts, such as LIMA/RIMA or the radial artery, are the same for women as for men.

Female IMAs are even thought to be physiologically different from male IMAs and could therefore contribute to worse outcomes in female CABG patients. Lamin et al. reported that female IMAs are more sensitive to serotonin-induced vasoconstriction and are therefore more prone to spasm[53].

Recently published American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions coronary artery revascularization guidelines suggest that the radial artery should be used as a second conduit rather than the saphenous vein. Studies have reported a patency rate for radial artery conduits similar to that of the IMA and have shown that using the radial artery as a second conduit significantly improves 5-year outcomes in women[54]. Dimitrova et al. demonstrated in 2013 an improved 15-year survival in women who received a radial artery conduit[55].

Long-term results in 310 radial artery grafts showed that the radial arteries had the lowest patency rate compared to IMA and saphenous vein grafts (SVGs). This study also demonstrated a significantly worse patency rate for radial artery grafts in women (38.9% vs. 56.1%, P-value = 0.025) and the female sex was independently associated with severe disease or occlusion of the radial artery. It is of note that there is a strong selection bias in this study as angiography was performed predominantly in symptomatic patients or when signs of recurrent ischemia were seen[56]. Women have a lower BSA and body mass index (BMI), have smaller coronary arteries and have also been shown to have smaller conduit arteries, such as the radial artery, even when indexed for BMI[57]. The smaller size of both the conduit and the coronaries could increase the difficulty of arterial revascularization in women and could be a reason why SVGs are the most commonly used conduits in women, despite a poorer patency rate and a higher susceptibility to occlusion compared to arterial grafts[58,59]. Women carry several risks that make them more prone to graft occlusion, including diabetes and small target coronary arteries. Whether female sex is associated with higher graft occlusion rates remains a matter of debate. Some studies demonstrate similar patency rates for SVGs in women and men; however, other studies report a significantly higher one-year angiographic occlusion rate of SVGs in women than in men (23.3% vs. 12%; P = 0.02). In contrast, one study showed that the radial artery had a lower one-year angiographic occlusion rate in women compared to men, although this was not statistically significant (5.3% vs. 8.6%; P = 0.06)[60].

OFF-PUMP CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS VERSUS ON-PUMP CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS

Off-pump coronary artery bypass (OPCAB) surgery in women remains an ongoing topic of debate. A review published by the STS Workforce on Evidence-Based Surgery suggests that there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate the superiority of OPCAB over on-pump coronary artery bypass (ONCAB) in women[61]. This was confirmed by a more recent systematic review, which included four trials and 13,193 patients. Again, no significant difference in outcomes was associated with OPCAB surgery, neither in men nor in women. In a systematic review that included 23,313 patients, Attaran et al. showed that there was no significant difference in 30-day mortality among female patients receiving OPCAB vs. ONCAB surgery[62]. In the study by ter Woorst et al., however, a decrease in perioperative MI was observed in women undergoing OPCAB. This suggests that OPCAB does not reduce 30-day mortality but does decrease short-term morbidity in female patients[63]. Further research on the effect of OPCAB in women is needed to determine whether this technique is truly beneficial. The GOPCAB trial showed no difference in outcomes for women (> 74 years of age) undergoing either on-pump or off-pump surgery[64]. As previously indicated by Puskas et al., experience is crucial in OPCAB surgery. In more experienced centers, mortality is lower than in less experienced centers, and this applies to both men and women[65]. A recent interesting study of Anwar et al. showed that, in an unmatched cohort, women had an increased cardiovascular mortality and inferior MACCE-free survival compared to men. After propensity matching, men and women had a similar outcome on cardiovascular mortality and MACCE-free survival[66]. The latter suggests that a worse outcome is determined by more risk factors in women compared to men.

Nathoe et al. found that female sex was independently associated with an increased risk of perioperative MI during off-pump surgery, again contradicting the claim that women benefit more from OPCAB than men. However, among patients who experienced a perioperative MI, the risk of adverse cardiac events one year after OPCAB was greater in men than in women {odds ratio [95%CI] = 6.20 [1.36-28.24], P = 0.02}[67]. In a review by Lopes et al., male patients had a higher risk of excessive blood loss after any type of cardiac surgery. However, the authors also describe factors more frequently present in women - such as lower BMI and diabetes mellitus - that increase the risk of excessive postoperative blood loss[68]. On the contrary, Shehata et al.[69] found that women receive more blood transfusions than men. Female sex was a factor associated with a two-fold increase in red blood cell transfusion in a systematic review of 21 studies. The study by Wang et al. demonstrates that the incidence of reintervention for bleeding or cardiac tamponade was lower in female patients than in male patients after CABG surgery[70].

SHORT-TERM OUTCOMES AFTER CABG

Differences in preoperative risk profiles between men and women have been extensively described. However, contradictory results remain regarding short-term postoperative outcomes. Gaudino et al.[52] reported no sex difference in perioperative mortality after CABG, although a higher incidence of perioperative MI was observed in women (6.3% vs. 5.2%). Findings regarding mid-term outcomes have also been inconsistent. This meta-analysis reported similar all-cause mortality for men and women; however, women had a significantly higher risk of MACCE during 5-year follow-up[2]. Another large meta-analysis reported a 12% higher risk of MACCE after CABG in women, as well as a 30% higher risk of MI and a 22% higher risk of repeat revascularization compared with men[52]. Other studies, including a systematic review by Kim et al., found a higher in-hospital all-cause mortality for women after coronary revascularization (Both PCI and CABG)[71]. An Ontario-based study of 54,425 patients demonstrated a higher 30-day mortality rate among female patients, even after risk adjustment[5]. Ter Woorst et al. found that early mortality after CABG was significantly higher in female patients than in male patients[30].

The study by Dalen et al. (2019) examined younger women undergoing CABG, a group known to have worse postoperative outcomes. Short-term results indicated poorer outcomes in women < 50 years; however, after risk adjustment, this difference was no longer observed. The study also reported a higher rate of repeat revascularization in younger women in the short-term analysis[72].

A recent national database study from the United Kingdom demonstrated that the odds of 30-day mortality were increased for women, not only in those undergoing CABG but also in those undergoing aortic valve replacement (AVR) and mitral valve replacement (MVR) surgery. This study also found that female sex is an independent risk factor after adjustment for other risk factors in patients undergoing CABG. Female patients additionally had an increased risk of postoperative dialysis, deep sternal wound infections, and extended length of hospital stay compared with males. Female patients had a lower risk of postoperative bleeding leading to re-operation. There were no sex-related differences in postoperative cerebrovascular accidents (CVA)[50].

Den Ruijter et al. found that women had worse outcomes after CABG, mainly driven by a higher percentage of women suffering from unstable angina, coronary revascularization, and congestive heart failure[44]. A higher prevalence of congestive heart failure among women in the immediate postoperative period was also described by Jacobs et al.[14].

LONG-TERM OUTCOMES AFTER CABG

The study by Hara et al. reported a higher all-cause mortality rate in women at 10 years after both PCI and CABG. However, after adjustment for baseline characteristics, female sex was not a predictor of all-cause mortality at 10 years[4]. Similarly, an earlier study by Koch et al. found no significant sex differences in

QUALITY OF LIFE

In addition to outcomes related to mortality, residual functional status and quality of life are expected to improve after CABG, especially in patients undergoing surgery to relieve symptoms. Studies have shown that, at baseline, women have significantly lower activity status than men. Activity status is measured using the Duke Activity Status Index (DASI), a questionnaire assessing daily activities by their metabolic cost. After surgery, activity status increases considerably for both men and women; however, a significant difference remains between sexes (DASI scores: men 51-58, 56.7% vs. women 31.7%). This difference persisted after adjustment for preoperative DASI scores, risk factors, postoperative complications, and propensity matching[74]. Women also have worse functional and mental status postoperatively[73]. A review by Vogel et al. emphasizes that female sex is a predictor of residual angina after coronary revascularization[17].

Depression after CAD, if left untreated, can significantly worsen patient prognosis[75]. Depression following CABG is more common in women than in men. A literature review reported that one week after CABG, the frequency of depression in women was more than double that of men (42.4% vs. 19.5%). Evaluation at six months showed a similar pattern, with 40.7% of women exhibiting depressive symptoms consistent with a potential diagnosis of depression, compared with 21.8% of men[76]. The review also described a correlation between sex and mortality among patients with depression: men diagnosed with depression had a 1.6-fold higher mortality risk, while women had a 2.0-fold higher risk of death after a post-CABG depression diagnosis[77]. In some cases, women experience postoperative residual or recurrent angina. Decreased quality of life and reduced functional status after surgery occur more frequently in women than in men. When unrecognized, these factors may contribute to a higher number of women being diagnosed with depression.

In addition to historically lower referral rates for female patients with anginal symptoms, differences in pathophysiology, treatment, and outcomes, and there is also a disparity in referral to cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs after coronary intervention[77]. CR programs are associated with improved CVD risk factor management, reduced hospital readmissions, and lower mortality. Additionally, CR positively influences quality of life and exercise capacity. Unfortunately, studies have shown sex disparities in both referral and attendance in CR programs[78,79]. Li et al. demonstrated that female patients are 12% less likely to be referred for CR, even though CR provides similar - and possibly greater - mortality benefits in women compared with men[80]. This represents a missed opportunity to improve survival after CABG in women. Reasons women are less likely to be referred to, attend, or complete CR include greater transportation challenges, family responsibilities, higher burden of comorbidities, and perceptions that exercise is too tiring or painful[78].

CONCLUSION

Over the years, evidence of differences in pathophysiology, symptom presentation, treatment, and outcomes of CAD in women and men has been accumulating. Female sex has therefore been included in the most commonly used risk scores for calculating operative risks in cardiac surgery. However, discussions persist concerning the underlying mechanisms leading to worse outcomes for female patients after CABG. Studies suggest that the more complex risk profile with which women present contributes to these outcome differences.

In this contemporary review of the literature, we found little evidence suggesting that female sex alone accounts for the higher mortality and morbidity rates in women. We emphasize that sex disparities in outcomes after CABG are multifactorial.

Differences in the presentation and pathophysiology of CAD result in less effective treatment by CABG, as the procedure has little or no effect on INOCA or microvascular disease, which are more common in female patients. In addition, when women undergo CABG, they are treated differently than men: they receive fewer arterial grafts, appear to have fewer anastomoses, and the use of the OPCAB technique differs between sexes. In the postoperative period, female patients receive more blood products and generally have longer intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital stays.

Short-term outcomes after CABG are especially worse in women. The 30-day postoperative mortality rate appears higher, and women seem to have more perioperative MI, reinterventions, and congestive heart failure.

Regarding long-term outcomes, women appear to have similar or even better outcomes compared with men when adjusted for risk factors. However, recurrent or residual angina and reintervention are more common in women than in men.

We also addressed sex differences in quality of life, depression, and CR participation, all of which influence mortality in female CABG patients.

In conclusion, we aimed to describe evidence for disparities in outcomes between men and women undergoing CABG. We emphasize the multifactorial nature of these disparities and hope to inspire further research on how women with CAD should be managed. Eliminating these disparities remains a challenge, requiring tailored treatment at all stages of disease for women with CAD.

Future perspectives

It is well known that women and men are physiologically different, and CAD manifests differently in the two sexes. Women more frequently suffer from microvascular disease or INOCA, for which CABG is not effective. However, treatment for severe obstructive CAD remains the same for men and women. This review highlights these differences and aims to inspire further research into the surgical treatment of CAD in women. More research is needed to determine which techniques are most effective for women and men - for example, which grafts are best suited for women.

It is important to establish whether women are treated according to guidelines, and whether these guidelines are equally applicable and optimal for female patients requiring CABG. Further questions - such as “Should we use OPCAB or conventional CABG in women?” or “Should the same transfusion thresholds apply, and are arterial grafts equally beneficial in women as in men?” - remain unanswered. Addressing these questions could help narrow the knowledge gap regarding female CABG patients and, in the future, reduce disparities in outcomes by enabling tailored treatment for women with CAD. Current clinical recommendations may suggest treating women the same as men, but women’s anatomy differs, and in some cases, further investigation into the underlying causes of coronary heart disease is warranted.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing - original draft, visualization: Wester ML

Writing - review and editing: Soliman-Hamad MA

Writing - original draft: von Meijenfeldt D

Writing - review and editing: Maas AHEM

Conceptualization, methodology, writing - original draft, supervision: ter Woorst JFJ

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Centraal bureau voor de statistiek (CBS). Available from https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/80202ned/table?ts=1734083164294 [accesses 8 December 2025].

3. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al.; Writing Committee Members. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:197-215.

4. Hara H, Takahashi K, van Klaveren D, et al.; SYNTAX Extended Survival Investigators. Sex differences in all-cause mortality in the decade following complex coronary revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:889-99.

5. Guru V, Fremes SE, Tu JV. Time-related mortality for women after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a population-based study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:1158-65.

6. Nashef SA, Roques F, Michel P, Gauducheau E, Lemeshow S, Salamon R. European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;16:9-13.

7. Ad N, Barnett SD, Speir AM. The performance of the EuroSCORE and the society of thoracic surgeons mortality risk score: the gender factor. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;6:192-5.

8. Kunadian V, Chieffo A, Camici PG, et al. An EAPCI expert consensus document on ischaemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries in collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on coronary pathophysiology & microcirculation endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3504-20.

9. Cho L, Kibbe MR, Bakaeen F, et al. Cardiac surgery in women in the current era: what are the gaps in care? Circulation. 2021;144:1172-85.

10. Mansur Ade P, Hueb WA, Takada JY, et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized, controlled clinical trial of three therapeutic strategies for multivessel stable coronary artery disease in women. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;19:997-1001.

11. Lansky AJ, Ng VG, Maehara A, et al. Gender and the extent of coronary atherosclerosis, plaque composition, and clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:S62-72.

12. Pepine CJ, Kerensky RA, Lambert CR, et al. Some thoughts on the vasculopathy of women with ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:S30-5.

13. Lawton JS. Sex and gender differences in coronary artery disease. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;23:126-30.

14. Jacobs AK, Kelsey SF, Brooks MM, et al. Better outcome for women compared with men undergoing coronary revascularization: a report from the bypass angioplasty revascularization investigation (BARI). Circulation. 1998;98:1279-85.

15. Frishman WH, Gomberg-Maitland M, Hirsch H, et al. Differences between male and female patients with regard to baseline demographics and clinical outcomes in the Asymptomatic Cardiac Ischemia Pilot (ACIP) Trial. Clin Cardiol. 1998;21:184-90.

16. Jamee A, Abed Y, Jalambo MO. Gender difference and characteristics attributed to coronary artery disease in Gaza-Palestine. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:51-6.

17. Vogel B, Goel R, Kunadian V, et al. Residual angina in female patients after coronary revascularization. Int J Cardiol. 2019;286:208-13.

18. Agarwala A, Michos ED, Samad Z, Ballantyne CM, Virani SS. The use of sex-specific factors in the assessment of women’s cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2020;141:592-9.

19. Maas AH, Appelman YE. Gender differences in coronary heart disease. Neth Heart J. 2010;18:598-602.

20. Tamis-Holland JE, Lu J, Korytkowski M, et al.; BARI 2D Study Group. Sex differences in presentation and outcome among patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease treated with contemporary medical therapy with or without prompt revascularization: a report from the BARI 2D Trial (Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1767-76.

21. Davis KB, Chaitman B, Ryan T, Bittner V, Kennedy JW. Comparison of 15-year survival for men and women after initial medical or surgical treatment for coronary artery disease: a CASS registry study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:1000-9.

22. Elkoustaf RA, Boden WE. Is there a gender paradox in the early invasive strategy for non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes? Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1559-61.

23. Shah SJ, Lam CSP, Svedlund S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of coronary microvascular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: PROMIS-HFpEF. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3439-50.

24. Mehta PK, Huang J, Levit RD, Malas W, Waheed N, Bairey Merz CN. Ischemia and no obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA): a narrative review. Atherosclerosis. 2022;363:8-21.

25. Nguyen LS, Baudinaud P, Brusset A, et al. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction as an independent risk factor of mortality after cardiothoracic surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156:188-193.e2.

26. Duca F, Zotter-Tufaro C, Kammerlander AA, et al. Gender-related differences in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1080.

27. Arslanian-Engoren C, Patel A, Fang J, et al. Symptoms of men and women presenting with acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1177-81.

28. Lehtinen ML, Harik L, Soletti G, et al. Sex differences in saphenous vein graft patency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Card Surg. 2022;37:4573-8.

29. Gaudino M, Di Franco A, Cao D, et al. Sex-related outcomes of medical, percutaneous, and surgical interventions for coronary artery disease: JACC Focus Seminar 3/7. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1407-25.

30. Woorst JF, van Straten AHM, Houterman S, Soliman-Hamad MA. Sex difference in coronary artery bypass grafting: preoperative profile and early outcome. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019;33:2679-84.

31. Serruys PW, Cavalcante R, Collet C, et al. Outcomes after coronary stenting or bypass surgery for men and women with unprotected left main disease: the EXCEL Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:1234-43.

32. Piña IL, Zheng Q, She L, et al.; STICH Trial Investigators. Sex difference in patients with ischemic heart failure undergoing surgical revascularization: results from the STICH Trial (surgical treatment for ischemic heart failure). Circulation. 2018;137:771-80.

33. Kirov H, Caldonazo T, Toshmatov S, et al. Survival trends of patients after coronary artery bypass grafting and sex-specific differences-a meta-analysis of reconstructed time-to-event data. Am J Cardiol. 2025;253:53-8.

34. Koch CG, Weng YS, Zhou SX, et al.; Ischemia Research and Education Foundation, Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group. Prevalence of risk factors, and not gender per se, determines short- and long-term survival after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2003;17:585-93.

35. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al.; INTERHEART Study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937-52.

36. Walli-Attaei M, Joseph P, Rosengren A, et al. Variations between women and men in risk factors, treatments, cardiovascular disease incidence, and death in 27 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;396:97-109.

37. Wenger N. Tailoring cardiovascular risk assessment and prevention for women: one size does not fit all. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2017;2017:e201701.

38. Campbell DJ, Somaratne JB, Jenkins AJ, et al. Differences in myocardial structure and coronary microvasculature between men and women with coronary artery disease. Hypertension. 2011;57:186-92.

39. Wang Y, O’Neil A, Jiao Y, et al. Sex differences in the association between diabetes and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 5,162,654 participants. BMC Med. 2019;17:136.

40. Edwards FH, Carey JS, Grover FL, Bero JW, Hartz RS. Impact of gender on coronary bypass operative mortality. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:125-31.

41. Clayton TC, Pocock SJ, Henderson RA, et al. Do men benefit more than women from an interventional strategy in patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction? The impact of gender in the RITA 3 trial. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1641-50.

42. Attia T, Koch CG, Houghtaling PL, Blackstone EH, Sabik EM, Sabik JF 3rd. Does a similar procedure result in similar survival for women and men undergoing isolated coronary artery bypass grafting? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:571-579.e9.

43. Sandoval Y, Brilakis ES, Canoniero M, Yannopoulos D, Garcia S. Complete versus incomplete coronary revascularization of patients with multivessel coronary artery disease. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2015;17:366.

44. den Ruijter HM, Haitjema S, van der Meer MG, et al.; IMAGINE Investigators. Long-term outcome in men and women after CABG; results from the IMAGINE trial. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:284-8.

45. Oertelt-Prigione S, Kendel F, Kaltenbach M, Hetzer R, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Baretti R. Detection of gender differences in incomplete revascularization after coronary artery bypass surgery varies with classification technique. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:108475.

46. Burgess SN, Juergens CP, Nguyen TL, et al. Comparison of late cardiac death and myocardial infarction rates in women vs men with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2020;128:120-6.

48. Lawton JS, Barner HB, Bailey MS, et al. Radial artery grafts in women: utilization and results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:559-63.

49. Jabagi H, Tran DT, Hessian R, Glineur D, Rubens FD. Impact of gender on arterial revascularization strategies for coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105:62-8.

50. Dixon LK, Dimagli A, Di Tommaso E, et al. Females have an increased risk of short-term mortality after cardiac surgery compared to males: Insights from a national database. J Card Surg. 2022;37:3507-19.

51. Loop FD, Lytle BW, Cosgrove DM, et al. Influence of the internal-mammary-artery graft on 10-year survival and other cardiac events. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1-6.

52. Gaudino M, Di Franco A, Alexander JH, et al. Sex differences in outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Eur Heart J. 2021;43:18-28.

53. Lamin V, Jaghoori A, Jakobczak R, et al. Mechanisms responsible for serotonin vascular reactivity sex differences in the internal mammary artery. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018:7.

54. Tatoulis J, Royse AG, Buxton BF, et al. The radial artery in coronary surgery: a 5-year experience--clinical and angiographic results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:143-7; discussion 147.

55. Dimitrova KR, Hoffman DM, Geller CM, et al. Radial artery grafting in women improves 15-year survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:1467-73.

56. Khot UN, Friedman DT, Pettersson G, Smedira NG, Li J, Ellis SG. Radial artery bypass grafts have an increased occurrence of angiographically severe stenosis and occlusion compared with left internal mammary arteries and saphenous vein grafts. Circulation. 2004;109:2086-91.

57. Kim SG, Apple S, Mintz GS, et al. The importance of gender on coronary artery size: in-vivo assessment by intravascular ultrasound. Clin Cardiol. 2004;27:291-4.

58. Hess CN, Lopes RD, Gibson CM, et al. Saphenous vein graft failure after coronary artery bypass surgery: insights from PREVENT IV. Circulation. 2014;130:1445-51.

59. Gharibeh L, Ferrari G, Ouimet M, Grau JB. Conduits’ biology regulates the outcomes of coronary artery bypass grafting. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2021;6:388-96.

60. Desai ND, Naylor CD, Kiss A, et al.; Radial Artery Patency Study Investigators. Impact of patient and target-vessel characteristics on arterial and venous bypass graft patency: insight from a randomized trial. Circulation. 2007;115:684-91.

61. Edwards FH, Ferraris VA, Shahian DM, et al.; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Gender-specific practice guidelines for coronary artery bypass surgery: perioperative management. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:2189-94.

62. Attaran S, Harling L, Ashrafian H, et al. Off-pump versus on-pump revascularization in females: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Perfusion. 2014;29:385-96.

63. ter Woorst JF, Hoff AHT, Haanschoten MC, Houterman S, van Straten AHM, Soliman-Hamad MA. Do women benefit more than men from off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting? Neth Heart J. 2019;27:629-35.

64. Faerber G, Zacher M, Reents W, et al.; GOPCABE investigators. Female sex is not a risk factor for post procedural mortality in coronary bypass surgery in the elderly: a secondary analysis of the GOPCABE trial. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184038.

65. Puskas JD, Gaudino M, Taggart DP. Experience is crucial in off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Circulation. 2019;139:1872-5.

66. Anwar A, Subash V, Radhakrishnan RM, et al. Long-term outcomes of women compared to men after off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting-a propensity-matched analysis. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2025;41:126-38.

67. Nathoe HM, Moons KG, van Dijk D, et al.; Octopus Study Group. Risk and determinants of myocardial injury during off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1482-6.

68. Lopes CT, Dos Santos TR, Brunori EH, Moorhead SA, Lopes Jde L, Barros AL. Excessive bleeding predictors after cardiac surgery in adults: integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:3046-62.

69. Shehata N, Naglie G, Alghamdi AA, et al. Risk factors for red cell transfusion in adults undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: a systematic review. Vox Sang. 2007;93:1-11.

70. Wang E, Wang Y, Hu S, Yuan S. Impact of gender differences on hemostasis in patients after coronary artery bypass grafts surgeries in the context of tranexamic acid administration. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022;17:123.

71. Kim C, Redberg RF, Pavlic T, Eagle KA. A systematic review of gender differences in mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery and percutaneous coronary interventions. Clin Cardiol. 2007;30:491-5.

72. Dalén M, Nielsen S, Ivert T, Holzmann MJ, Sartipy U. Coronary artery bypass grafting in women 50 years or younger. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013211.

73. Vaccarino V, Lin ZQ, Kasl SV, et al. Gender differences in recovery after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:307-14.

74. Koch CG, Khandwala F, Cywinski JB, et al. Health-related quality of life after coronary artery bypass grafting: a gender analysis using the Duke Activity Status Index. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:284-95.

75. Stanicki P, Szarpak J, Wieteska M, Kaczyńska A, Milanowska J. Postoperative depression in patients after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) - a review of the literature. Pol Przegl Chir. 2020;92:32-8.

76. Korbmacher B, Ulbrich S, Dalyanoglu H, et al. Perioperative and long-term development of anxiety and depression in CABG patients. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;61:676-81.

77. Geulayov G, Novikov I, Dankner D, Dankner R. Symptoms of depression and anxiety and 11-year all-cause mortality in men and women undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. J Psychosom Res. 2018;105:106-14.

78. Smith JR, Thomas RJ, Bonikowske AR, Hammer SM, Olson TP. Sex differences in cardiac rehabilitation outcomes. Circ Res. 2022;130:552-65.

79. Feola M, Garnero S, Daniele B, et al. Gender differences in the efficacy of cardiovascular rehabilitation in patients after cardiac surgery procedures. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2015;12:575-9.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].