CCL17 in pan-vascular diseases: current research advances

Abstract

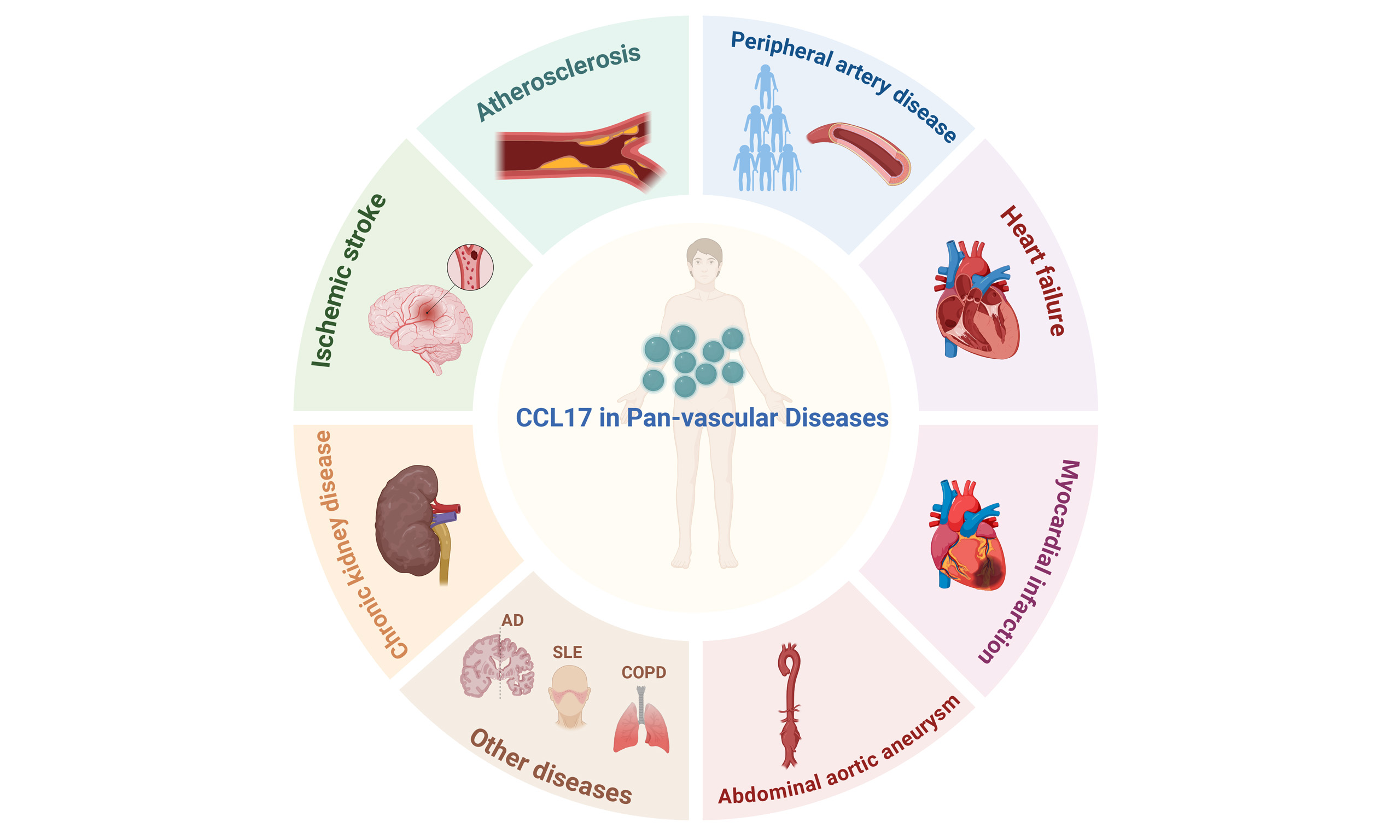

Pan-vascular diseases comprise a spectrum of atherosclerosis-driven vascular disorders that involve multiple vital organs, including the heart, brain, kidneys, and peripheral circulation. Despite being distributed across different clinical specialties due to increasing medical subspecialization, conditions such as coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, and peripheral artery disease are interconnected manifestations of a unified, systemic vascular pathology. This conceptual shift highlights the need to consider these disorders within an integrated pan-vascular framework rather than as isolated clinical entities. Inflammation is a central driver in pan-vascular pathogenesis, accelerating atherosclerosis and increasing cardiovascular event risk. In the inflammatory cascade of pan-vascular diseases, chemokines play a pivotal role as regulators, facilitating the recruitment and activation of immune cells. C-C motif chemokine ligand 17 (CCL17) is essential for T cell development in the thymus. It binds to the C-C chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4) and exhibits chemotactic activity towards T lymphocytes, mainly T helper 2 (Th2) cells and regulatory T cells. This review summarizes the biological properties of CCL17, its mechanistic roles in pan-vascular pathologies, and its clinical translational potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Pan-vascular diseases share a common pathophysiological basis, encompassing endothelial dysfunction, chronic low-grade inflammation, immune cell activation and infiltration, and atherosclerosis with its complications (such as thrombosis and aneurysms), which collectively impose a substantial health burden[1]. Inflammation constitutes the core pathological mechanism across pan-vascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), and peripheral artery disease (PAD)[2]. The innate immune system serves as the initial defense against vascular injury. An inflammatory cascade is triggered when pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), thereby initiating adaptive immune responses. Furthermore, an imbalance among T-cell subpopulations is a central driver of chronic inflammation in pan-vascular diseases, with distinct T-cell subsets critically shaping disease phenotypes through their intricate cytokine networks[3].

Early research established a critical role for C-C motif chemokine ligand 17 (CCL17) in thymic T cell development. Imai et al. first identified it as a protein consistently expressed in the thymus in 1996[4]. The name was initially given due to its chemotactic effect on cells with C-C chemokine receptor type 4, mainly T cells[5]. Secreted by a wide array of cell types, CCL17 contributes to the pathogenesis of various diseases. This review aims to summarize the diverse biological activities of CCL17, highlight its role in vascular diseases, and consider its potential as a diagnostic and therapeutic option.

CCL17 BIOLOGY

The human CCL17 gene is located on chromosome 16q13 and comprises 2,176 base pairs, spanning four exons. The human CCL17 monomer is an 8.1-kDa protein consisting of 71 amino acids and a 23-amino acid signal peptide[4]. The CCL17 dimer has a unique asymmetric structure not found in other C-C chemokines[4,5].

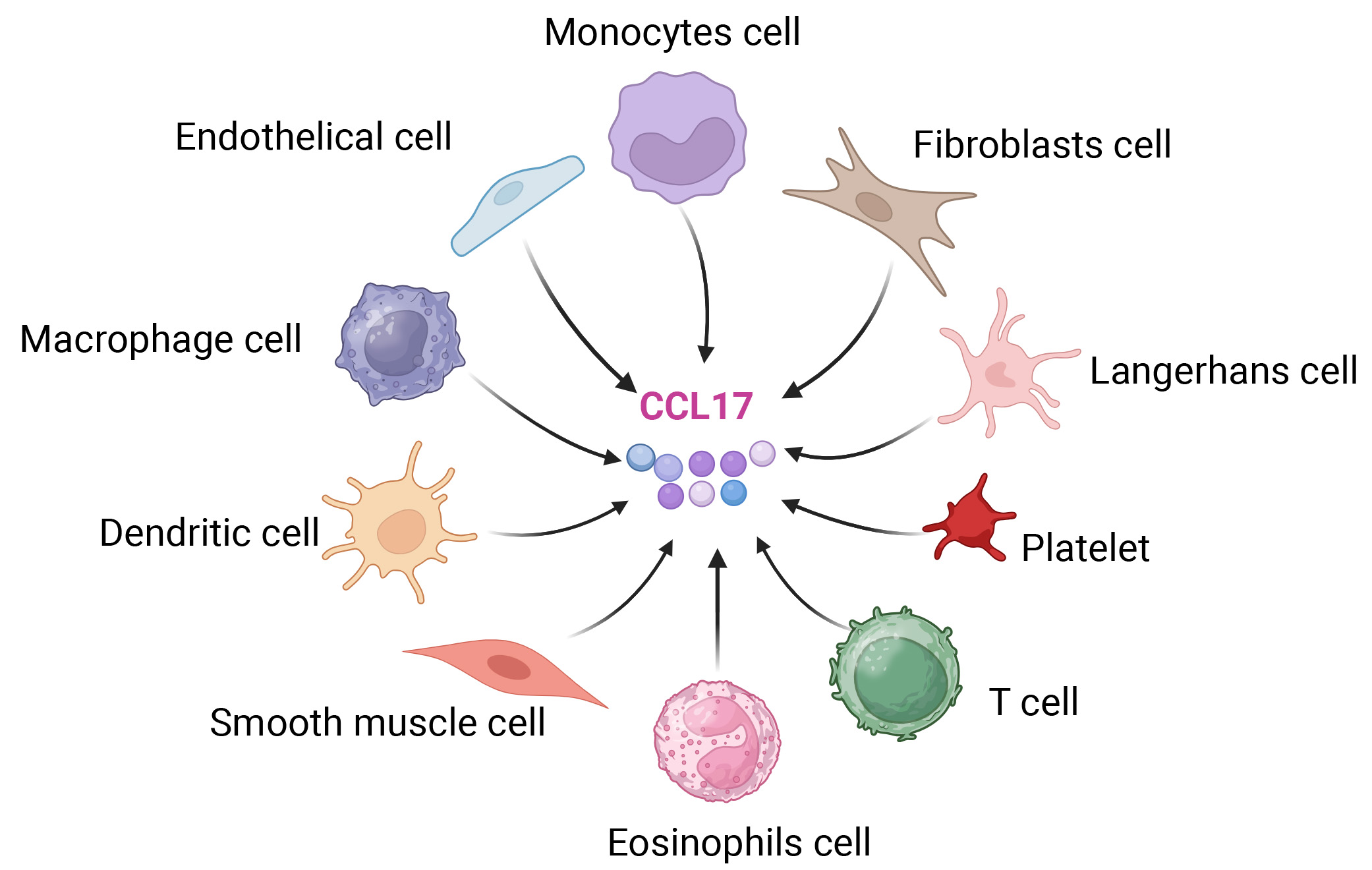

CCL17 expression extends beyond the thymus and is produced by diverse cell types across multiple tissues [Figure 1]. This group comprises monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), eosinophils, epithelial cells such as keratinocytes, Langerhans cells, fibroblasts, platelets, and various T-cell subsets[6,7]. The biological role of CCL17 is strongly associated with T cells, mainly because its receptor, C-C chemokine receptor (CCR)4, is found predominantly on Th2 cells[3]. Therefore, CCL17 selectively attracts Th2 cells, affecting Th2-type immune responses and playing a role in immune tolerance. CCR4 is also found on various cell types, such as T helper 17 (Th17) cells, T helper 22 (Th22) cells, regulatory T (Treg) cells, natural killer (NK) cells, Tc2 cells (type 2 CD8+ T cells), and skin-homing T cells that express cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA)[5]. CCR4 is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that primarily interacts with its endogenous ligands CCL17 and CCL22. Of particular significance, CCL22 is a chemokine that exhibits particularly high expression levels in the thymus[4].

Figure 1. Cell sources of C-C motif chemokine ligand 17. Cell types: Morphologically and color-distinguished cells (monocytes cell, endothelial cells, macrophages cell, dendritic cells, smooth muscle cells, eosinophils cells, T cells, platelets, Langerhans cells, fibroblasts cell) are the secretory sources of CCL17; Arrows: Black arrows indicate that all listed cell types can secrete CCL17; CCL17 representation: The central colored spherical structures correspond to CCL17 molecules. Created in BioRender. YAN, W. (2025) https://BioRender.com/nz9htta.

Furthermore, CCR4 expression has been observed in additional cell populations, including airway eosinophils, megakaryocytes, and platelets[3], suggesting a potential role for CCL17 in modulating the trafficking of these cells under specific conditions. Moreover, CCL17 has been demonstrated to enhance the migratory responses induced by other chemokines[4]. Research in a murine model of skin inflammation revealed an indirect necessity for CCL17 in the CCR7- and CXCR4-driven migration of DCs residing in the skin[8]. Similarly, work in a vaccination model showed that CCL17 is essential for the movement of mature CCR7-positive DCs in response to CCL19[9]. Despite its inability to bind CCR7 directly, these observations imply that CCL17 exerts an indirect influence on CCR7-mediated migratory processes. The interaction between CCL17 and CCR4 triggers downstream signaling events upon engagement of both receptor binding sites[5,6]. Given that CCL17 and CCL22 can exhibit distinct, and sometimes antagonistic, functions through CCR4, this concise review will focus specifically on the biology of CCL17, rather than a broader discussion of CCR4 or CCL22.

CCL17 IN PAN-VASCULAR DISEASES

Pan-vascular medicine investigates not only the microscopic mechanisms of atherosclerosis but also its development within the systemic context. It further compares the commonalities and specificities of target organ damage and repair processes, aiming to establish a conceptual framework for the management and prevention of pan-vascular disorders. Table 1 summarizes the role of CCL17 in various pan-vascular diseases, including the involved cell types, directions of action, and experimental models.

The role of CCL17 in different pan-vascular diseases

| Disease | Cell type | Direction of action | Model | Key signaling pathway/mechanism | References |

| Atherosclerosis | Dendritic cells and Treg cell | Recruit Treg cells and promote foam cell formation | Apo E-/- mouse atherosclerosis model | CCL17-CCR4 → Release of inflammatory cytokines | [15,17] |

| Myocardial Infarction | Treg cells | Recruit Treg cells to the injured heart | Mouse myocardial infarction model (LAD ligation) | GM-CSF → STAT5/NF-κB → CCL17-CCR4 | [24] |

| Cardiac Hypertrophy | Macrophages and Treg cell | Decrease inflammatory macrophages and recruit Treg cells | Mouse transverse aortic constriction | NF-κB (p50/p65)-CCL17 signaling pathway | [29] |

| Cardiac Hypertrophy | Th1 cell, Th2 cell, Th17 cell and Treg cell | Decrease Th2 cell and Th17 cell; Increase Th1 cell and Treg cell | Ang-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy model in mice | CCL17-CCR4-Th2 cell/Treg cell | [27] |

| Kidney Disease | Th2 cell, Treg cell, and dendritic cells | Recruit Th2 cells, Treg cells, and dendritic cells | Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion model | CCL17-CCR4-Th2 cell/Treg cell | [39] |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease | Th1 cell, Th2 cell , Th17 cell and Treg cell | Vascular remodeling | Ang-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy model in mice and aged mice | CCL17-CCR4-Th2 cell/Treg cell | [18] |

Atherosclerosis, a prevalent pathological condition impacting the coronary, cerebral, and peripheral arterial systems alongside the aorta, stands as a leading contributor to worldwide deaths. The process involves more than simple cholesterol accumulation; it comprises a range of physiological abnormalities such as impaired endothelial function and a complex bidirectional interaction of inflammatory and immunomodulatory pathways[10].

The understanding of atherosclerosis as a condition driven by inflammation, first suggested by Rudolph Virchow in 1856, became widely established following the publication of Russell Ross’s 1999 paper “Atherosclerosis - an Inflammatory Disease” in the New England Journal of Medicine[2,11]. This seminal work prompted a fundamental shift in perspective, leading the research community to acknowledge the multifaceted nature of the disease, which involves not only lipid deposition but also active inflammatory and immunological mechanisms. While traditional risk factors - including elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), hypertension, tobacco use, and diabetes - remain major contributors, growing evidence highlights the significant involvement of immune processes. Ongoing investigation into cellular and molecular interactions continues to clarify how these elements collectively drive disease development[4,12].

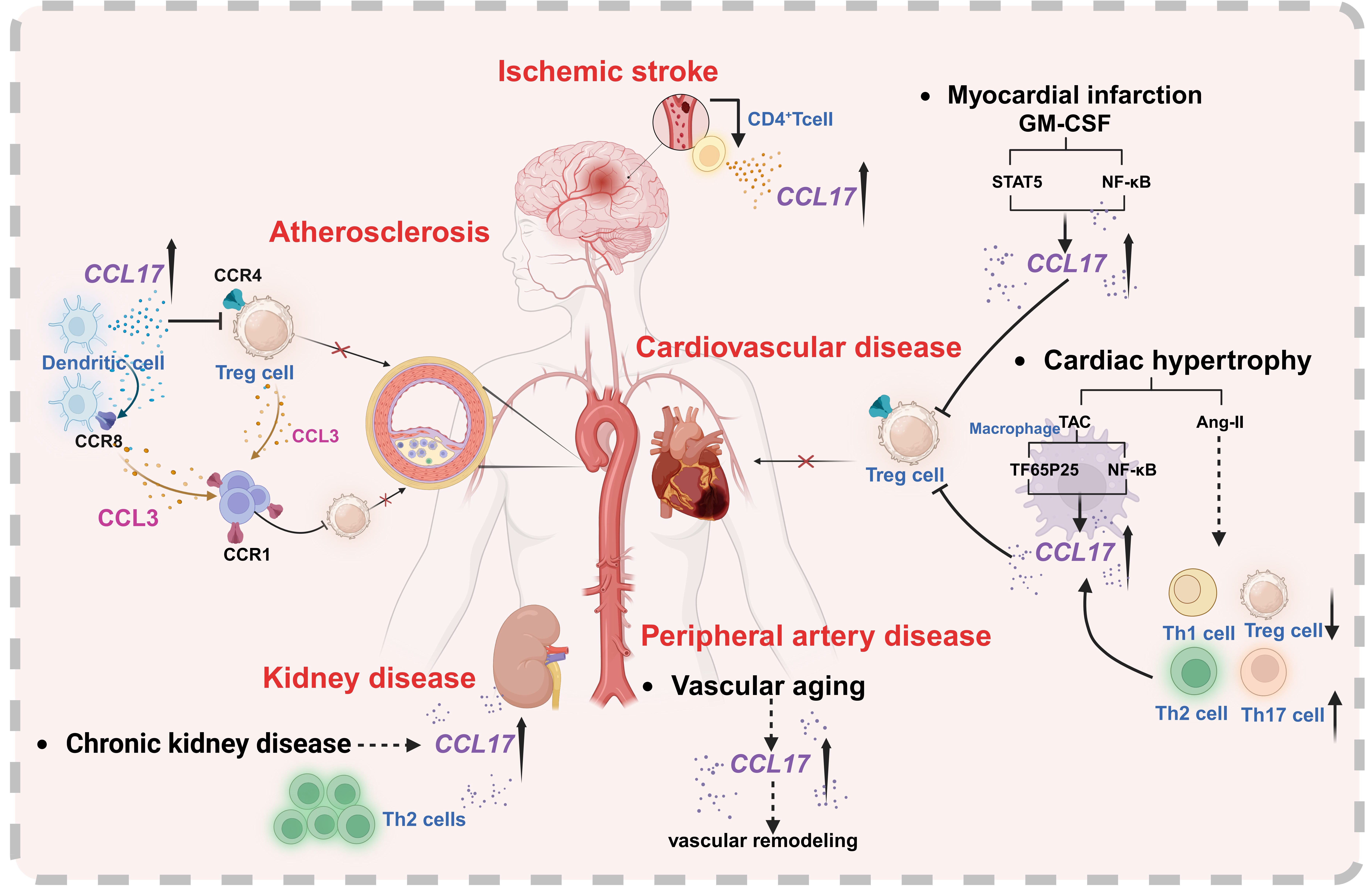

It has been shown that in addition to monocytes/macrophages, other mononuclear cells, namely T cells and DCs, can be detected within atherosclerotic lesions[13]. As professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs), DCs comprise several subtypes and are essential for initiating immune responses[14]. The chemokine CCL17, secreted by DCs, is detectable in advanced atherosclerotic lesions in both humans and mice, and DCs expressing CCL17 are found to accumulate within these plaques. Studies using mouse models susceptible to atherosclerosis show that knocking out the Ccl17 gene reduces plaque formation, a process that depends on Treg cells. Furthermore, CCL17 production by DCs was shown to suppress the expansion of Tregs by interfering with their survival and stability, thereby exacerbating atherosclerosis through a T-cell-mediated mechanism[15] [Figure 2].

Figure 2. The putative cell-specific effects and signaling pathways of CCL17 in atherosclerosis, peripheral artery disease, cardiovascular disease, ischemic stroke, and kidney disease. Key participants include CCL17-producing/target cells (dendritic cells, Treg, CD4+T, macrophages, Th1/Th2/Th17 cells) and chemokine-receptor pairs (CCL17/CCL3; CCR4/CCR1/CCR8) mediating intercellular crosstalk. Created in BioRender. YAN, W. (2025) https://BioRender.com/1opgqm0.

However, the exact molecular mechanisms by which DC-derived CCL17 regulates Treg cell homeostasis remain poorly understood, particularly the key soluble factors or receptor interactions that may be involved. Although CCR4 is widely recognized as the primary signaling receptor for CCL17 and has been shown to facilitate Treg recruitment and function in vivo[16], genetic ablation of CCR4 failed to reproduce the enhanced Treg activity and attenuated atherosclerosis seen in Ccl17-deficient mice[15].

Emerging evidence indicates that Ccl17-knockout mice exhibit a pronounced tolerogenic phenotype and transcriptional profile, which is not observed in animals lacking the canonical receptor CCR4. Plasma analysis of Ccl17-knockout mice showed a selective reduction in CCL3, with no other cytokines or chemokines significantly altered. Mechanistically, CCL17 was found to signal through CCR8 as an alternative high-affinity receptor. Signaling through CCR8 was shown to drive CCL3 expression and impair Treg cell functionality via a CCR4-independent pathway. Furthermore, genetic deletion of either Ccl3 or Ccr8 in CD4+ T cells led to diminished CCL3 production, expansion of FoxP3+ Treg populations, and amelioration of atherosclerotic lesion development[17] [Figure 2]. However, translation of these effects to humans requires caution, as the low expression of CCR8 in human Tregs may limit the efficacy of CCL17 blockade.

Peripheral artery disease

PAD represents a critical manifestation within the pan-vascular disease spectrum, driven centrally by chemokine-directed immune cell recruitment. A recent community-based cohort study reported higher circulating concentrations of CCL17 and greater brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) - an established indicator of arterial stiffness - among elderly participants relative to younger adults. Notably, serum CCL17 levels showed a significant positive correlation with baPWV[18]. Consistent with these clinical findings, elevated levels of CCL17 protein were also observed in the aortic tissue of aging mice and in those subjected to angiotensin II (Ang II) infusion. Notably, although aging wild-type animals developed heightened vascular stiffness, this effect was significantly reduced in aged mice lacking Ccl17. These results offer initial experimental evidence positioning the chemokine CCL17 as a novel and precise therapeutic target for mitigating vascular dysfunction associated with aging or provoked by risk factors including Ang II and hypertension[18] [Figure 2].

AAA represents a serious cardiovascular condition characterized by chronic inflammation. In the early phase of AAA development, monocytes from the circulation are recruited to the aortic wall and subsequently differentiate into macrophages, which then undergo activation. This inflammatory cascade drives destruction of the arterial wall, leading to progressive aortic dilation and the potential for life-threatening rupture[19]. Given its established role in immune cell recruitment across vascular pathologies, CCL17 is hypothesized to contribute to immune cell infiltration and disruption of vascular homeostasis in AAA, positioning it as a potential key factor in the disease process.

Cardiovascular disease

A preliminary clinical investigation revealed that serum CCL17 concentrations are independently correlated with the presence of coronary artery disease (CAD) and the extent of atherosclerotic burden, even after controlling for conventional cardiovascular risk factors. The study enrolled 971 consecutive patients, comprising 158 non-CAD controls and 813 CAD patients. Serum CCL17 levels were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Atherosclerosis severity was evaluated in all participants using the Gensini score (GSS). Importantly, a significant positive linear trend was observed between increasing quartiles of serum CCL17 levels and the GSS[20].

In patients diagnosed with pan-vascular disease, the annual occurrence rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) - comprising cardiovascular mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke - rose in correlation with the number of affected vascular beds, escalating from 2.2%-9.2%[21].

Elevated levels of circulating monocytes and heightened expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines are linked to maladaptive left ventricular (LV) remodeling and increased cardiovascular mortality after MI[22]. Mechanistically, a recent study demonstrated that CCL17 inhibits Treg recruitment via biased activation of CCR4 towards Gq signaling. Furthermore, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) signaling serves as a critical regulatory mediator for CCL17 expression, and this regulatory effect is achieved by means of synergistic activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) as well as canonical nuclear factor κ-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling pathways [Figure 2]. These findings demonstrate that Tregs play a key role in mediating the cardioprotective benefits observed following Ccl17 deletion, attenuating inflammatory responses in the myocardium and limiting maladaptive LV remodeling after MI[23]. Furthermore, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors represent a novel therapeutic avenue for MI. Supporting this, another study utilizing proteome-wide Mendelian randomization identified apolipoprotein B (APOB) and CCL17 as causal mediators of the protective effects of SGLT2 inhibition against MI[24].

Recent clinical research has utilized CCL17 as an inflammatory biomarker to identify plasma proteins with pathophysiological relevance in heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). This study further correlated CCL17 levels with treatment responses to spironolactone, revealing a significant differential effect of CCL17 on the instantaneous risk of hospitalization between the verum (spironolactone) and placebo groups[25]. Supporting these findings, a population-based cohort study revealed that serum concentrations of CCL17 rise with advancing age and correlate with impaired cardiac function in HF patients[26]. In parallel, studies in animal models indicated that genetic ablation of Ccl17 (Ccl17-/-) markedly reduced both aging-related and Ang II-triggered cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. This was accompanied by decreased production of the Th2-associated cytokine interleukin (IL)-4 and the Th17-related cytokine IL-17 in Ccl17-deficient mice. Notably, interventional use of a neutralizing antibody targeting CCL17 was found to potently suppress Ang II-induced maladaptive cardiac remodeling[26] [Figure 2].

The traditional Chinese medicine formulation LuQi (LQF) has been shown to be both safe and efficacious in the management of HF[27]. In vivo studies utilizing a mouse model of HF induced by transverse aortic constriction (TAC) revealed upregulated CCL17 expression within cardiac tissue. Treatment with LQF was found to suppress the infiltration of inflammatory macrophages through downregulation of the NF-κB (p50/p65)-CCL17 signaling pathway, while simultaneously promoting the recruitment of cardiac Treg cells, thereby conferring protection against HF progression[28] [Figure 2].

Ischemic stroke

As the atherosclerotic plaque progresses, it can be followed by pathological processes such as plaque erosion/rupture and thrombosis, which are considered to be the main pathological basis of most acute ischemic events such as acute MI, ischemic stroke or severe limb ischemia[29]. Inflammation constitutes a pivotal pathological mechanism in stroke pathogenesis. During the acute phase, the inflammatory cascade may be initiated through two primary pathways: (i) within the systemic circulation, characterized by leukocyte activation and cytokine release secondary to regional cerebral blood flow cessation[30] or (ii) within the brain parenchyma, driven by tissue hypoxia that induces reactive astrogliosis, microglial activation, and subsequent neuronal demise[31,32].

A research team prospectively collected blood samples from 75 consecutive patients diagnosed with acute anterior circulation large vessel occlusion (LVO)-related ischemic stroke who subsequently underwent endovascular thrombectomy (EVT). Multivariate analysis, with adjustments for age, intravenous thrombolysis use, pre-treatment National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, and Alberta Stroke Programme Early CT Score (ASPECTS), was employed to ascertain the relationship between post-procedural blood levels of CCL17, measured at the occlusion site, and 90-day disability, as assessed by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). CCL17/TARC levels demonstrated an inverse correlation with mRS scores[33]. These findings reveal a distinct profile of inflammatory factors in the blood obtained directly from the site of cerebrovascular occlusion. The significant correlations between these acute-phase biomarkers and functional outcome provide a rationale for exploring adjunctive immunomodulatory strategies in the management of acute ischemic stroke.

Previous investigations utilizing a transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) model demonstrated that ischemic stroke significantly alters pulmonary immune cell composition. These alterations include elevated proportions of alveolar macrophages, neutrophils, and CD11b+ DCs, alongside decreased frequencies of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, B cells, NK cells, and eosinophils. This remodeling of the pulmonary immune microenvironment occurs simultaneously with a pronounced decline in the expression of numerous chemokines, such as CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL17, CCL20, CCL22, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)5, CXCL9, and CXCL10[34]. To our knowledge, this work provides the first evidence of a coordinated reduction in pulmonary lymphocyte populations and a wide array of inflammatory chemokines following ischemic stroke in a murine model.

Studies on ischemic stroke-related disease models discussed above have been conducted in both human cohorts and murine animal models. CCL17 exhibits heterogeneous functional profiles across distinct species and disease subtypes, which may be ascribed to interspecies functional disparity, disease subtype-specific functional differentiation, and the insufficient elucidation of spatiotemporal dynamic regulatory networks.

The mechanism of the pathological role of CCL17 in cerebrovascular diseases, especially ischemic stroke, is somewhat controversial. We believe that CCL17 may contribute to disease progression by recruiting Th2 cells that participate in acute neuroinflammatory amplification, while paradoxically facilitating chronic-phase reparative processes (e.g., angiogenesis, glial scar formation). Concurrently, CCL17-mediated recruitment of Treg cells may fulfill neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and pro-reparative functions. While the precise pathogenic mechanisms underlying this functional heterogeneity remain incompletely understood, this phenomenon is highly intriguing and merits in-depth exploration in subsequent investigations.

Kidney disease

Individuals diagnosed with chronic kidney disease (CKD) face a substantially increased risk of developing cardiovascular complications. CKD patients have a higher incidence and prevalence of mediated cardiac disorders and MACEs such as HF, arrhythmias, acute coronary syndrome (ACS) based on CAD, stroke, venous thromboembolism, and PAD than the general population[35]. A considerable number of renal diseases are associated with inflammation, which results in a continuous decline of renal function. As the disease progresses, leukocytes migrate into the renal mesangium or the interstitial space. Chemokines, which are generated by intrinsic renal cells in response to immunological, toxic, ischemic, or mechanical insults during the initial and amplifying phases of renal inflammation, function as attractants for these leukocytes[36].

Acute kidney injury is predominantly caused by the increase of neutrophils and monocytes[37], whereas T cells, macrophages, and DCs play a role in the progression of renal failure to CKD[38]. CCL22 and CCL17, among others, recruit Th2 cells, Treg cells, and DCs by their attachment to the CCR4 receptor[39]. Consequently, the researchers sought to assess the potential of blood and urine chemokine levels as biomarkers for disease progression and risk assessment in a cohort of 114 CKD patients and 21 healthy volunteers. The chemokines that were the focus of this study were CCL17, CCL20, CCL22, and CXCR4. It has been established that these chemokines play a role in the development of chronic renal failure[40].

Numerous CKD patients suffer from moderate-to-severe itching. CKD-associated pruritus (CKD-aP) is a chronic and distressing illness that can have a negative impact on quality of life[41]. This retrospective analysis utilized data from 851 participants across two randomized phase 3 trials of difelikefalin. Biomarker samples were obtained at baseline (prior to treatment initiation) and again at week 12. According to multiple regression analysis, baseline itch severity was associated with levels of various chemokines and inflammatory markers, including CCL2, CCL17, CCL22, CCL27, CXCL10, CXCL11, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), IL-2, IL-31, and nerve growth factor (NGF)[42]. The role of immune and pruritic mediators in the pathogenesis of CKD-aP remains to be fully elucidated, with only a limited number of mediators having been the subject of investigation thus far. Determining which specific mediators are associated with CKD-aP pathophysiology is challenging because many patients with advanced CKD have comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic liver disease, or hematological diseases. Each of these comorbidities is associated with elevated inflammatory activity.

In summary, chemokine expression patterns dynamically evolve throughout the progression from early to end-stage CKD, exhibiting significant variations depending on the underlying etiology of renal failure. Nevertheless, these findings necessitate larger, well-designed clinical studies incorporating increased patient cohorts and matched controls to definitively establish the roles of specific chemokines in CKD pathogenesis and progression.

CLINICAL TRANSLATION PROSPECTS AND CHALLENGES

CCL17 holds significant promise as a biomarker for pan-vascular diseases. Its potential applications include: (i) serving as a predictor for the risk of acute vascular events by reflecting disease activity through monitoring CCL17 levels in biological samples across various disease stages; and (ii) acting as a prognostic marker to monitor treatment outcomes. Furthermore, the "pan-vascular" nature of CCL17 suggests its utility as a marker for assessing systemic vascular disease burden.

However, the specificity of CCL17 as a pan-vascular disease biomarker is compromised by its established roles in other pathologies. CCL17 is recognized as the most reliable Alzheimer’s disease biomarker[7], with levels strongly correlating with disease severity and serving to assess therapeutic efficacy[43]. Furthermore, CCL17 elevation in asthmatic bronchoalveolar lavage fluid has been proposed to drive CCR4+ Th2 cells migration into the lungs[44]. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), elevated CCL17 in airway epithelia and lavage fluid predicts rapid lung function decline (forced expiratory volume in 1s), a pattern also observed in serum from individuals exposed to high air pollution[45]. Similarly, increased serum CCL17 (with reduced CXCL9) forecasts a decline in lung function in cases of chronic bird-related hypersensitivity pneumonitis[46]. At the same time, elevated levels are related to severe interstitial lung disease in both children and adults[47]. There is growing evidence that CCL17 plays a role in other autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, indicating a need for further study in preclinical settings.

In addition, off-target toxicities must be carefully evaluated when developing therapeutic strategies targeting the CCL17/CCR4 axis, as these unintended effects can directly undermine treatment safety and amplify the risk of systemic immunosuppression - critical concerns that demand rigorous preclinical validation prior to clinical translation. Beyond its pro-inflammatory role in pan-vascular pathogenesis, CCL17 exerts pleiotropic physiological functions, particularly in sustaining immune homeostasis through orchestrating the recruitment and functional equilibrium of Treg cells, Th2 cells, and DCs[15,24].These cell populations are indispensable for suppressing aberrant inflammatory cascades and mediating tissue repair responses, underscoring the delicacy of the immune network modulated by CCL17. Non-selective blockade of CCL17 may disrupt this finely tuned immune balance, culminating in unintended immunosuppression characterized by impaired pathogen clearance (e.g., viruses, bacteria) and heightened vulnerability to opportunistic infections. Notably, in a murine model of viral myocarditis, genetic ablation of Ccl17 aggravated myocardial fibrosis and cardiomyocyte apoptosis by augmenting Treg cell infiltration into the injured myocardium[48]. This finding highlights that CCL17-mediated immunomodulation can exert protective effects in specific disease contexts, suggesting that systemic CCL17 inhibition in pan-vascular disease patients - many of whom present with comorbidities such as diabetes, CKD or age-related immune senescence may further compromise host defense mechanisms and increase infection-associated morbidity.

Another critical safety consideration arises from the overlapping receptor usage of CCL17. As CCL17 and CCL22 both bind to CCR4 with high affinity, targeted interventions against CCL17 may inadvertently perturb CCL22-CCR4 signaling cascades[4,16]. CCL22 plays a pivotal role in maintaining tissue-specific immune tolerance, especially in constraining excessive pro-inflammatory responses in organs including the skin, lungs, and kidneys[39,46]. Consequently, such cross-interference could disrupt tissue-specific immune regulation, potentially precipitating autoimmune reactions or exacerbating pre-existing inflammatory disorders (e.g., atopic dermatitis, interstitial lung disease) in susceptible individuals[44,46]. Furthermore, the involvement of CCL17 in multiple non-vascular pathological processes - including Alzheimer’s disease, asthma, and CKD-associated pruritus[7,39,44] implies that systemic CCL17 inhibition may elicit off-target effects in these organs, thereby complicating the risk-benefit assessment for pan-vascular disease patients with comorbid conditions.

Beyond immunosuppression and off-target perturbations, the spatiotemporal dynamism of CCL17’s biological functions across distinct disease stages introduces an additional layer of complexity. For example, in ischemic stroke, CCL17 has been shown to promote acute neuroinflammation via Th2 cell recruitment, while simultaneously facilitating tissue repair during the chronic phase through Treg cell activation and angiogenic signaling pathways[33,34]. Inappropriate timing of CCL17 blockade - such as targeting the chronic reparative phase - could hinder tissue healing and deteriorate long-term clinical outcomes. Similarly, in atherosclerosis, CCL17 drives lesion progression by suppressing Treg cell homeostasis[15]; however, its role in post-MI repair remains context-dependent, with evidence indicating both pathogenic and protective effects[24,48]. Indiscriminate CCL17 inhibition may therefore attenuate pathogenic inflammation while concurrently abrogating beneficial repair mechanisms, underscoring the need for precision in therapeutic design.

To address these safety challenges and fully harness the therapeutic potential of CCL17 targeting, several key research directions require advancement. Firstly, the development of highly selective CCL17-targeted agents (e.g., humanized monoclonal antibodies, structure-based small-molecule inhibitors) that minimize cross-reactivity with CCL22 or other CCR4 ligands, thereby reducing off-target immune perturbations[49]. Moreover, the exploration of lesion-specific drug delivery systems (e.g., vascular wall-homing nanoparticles, pathology-associated aptamer conjugates) to concentrate therapeutic agents at pan-vascular lesions, limiting systemic exposure and preserving physiological CCL17 functions in non-target tissues. Finally, the definition of stage-specific and patient-stratified therapeutic windows, guided by predictive biomarkers such as CCL17 expression levels, immune cell subset ratios (e.g., Treg/Th2 balance), and comorbidity profiles, to avoid immunosuppression in contexts where CCL17 exerts protective effects; and fourth, the selection of comprehensive clinical endpoints that integrate both vascular efficacy outcomes (e.g., plaque stabilization, aneurysm regression, freedom from MACEs) and safety parameters (e.g., infection incidence, autoimmune complications, multi-organ function). Only through rigorous preclinical and translational validation of these precision strategies can the therapeutic potential of CCL17 targeting be fully realized, while mitigating the risks of nonspecific immunosuppression and off-target toxicity.

DISCUSSION

As a key chemokine closely associated with T-cell biology, CCL17 has emerged as a central mediator in the pathogenesis of pan-vascular diseases. It links inflammatory cascades across different vascular beds, offering a highly promising "pan-vascular" therapeutic target for these disorders. This review systematically elaborates on the diverse mechanisms by which CCL17 regulates the pathological processes of pan-vascular diseases: by binding to canonical (CCR4) and non-canonical (CCR8) receptors on the surface of target cells (including Treg cells, Th2 cells, DCs and macrophages), CCL17 modulates downstream signaling pathways, thereby regulating immune cell recruitment, release of inflammatory mediators, and vascular remodeling. From accelerating atherosclerotic plaque progression by suppressing Treg cell homeostasis to driving vascular aging and pathological cardiac hypertrophy, from participating in neuroinflammatory responses in ischemic stroke to potentially mediating renal inflammatory injury in CKD, CCL17 exhibits context-dependent yet consistently critical roles across the pan-vascular disease spectrum. Its ability to connect the development of lesions in various organs highlights its potential as a unified therapeutic target to address the systemic nature of these diseases.

Despite the highly insightful findings summarized above, several critical gaps remain in our understanding of CCL17’s biological characteristics and its translational applications. Current evidence primarily relies on small-scale studies or preclinical models; therefore, large-scale prospective clinical cohort studies are urgently needed to validate the value of CCL17 in risk stratification for acute ischemic events and risk prediction of cardiovascular complications in CKD patients. At the preclinical level, the spatiotemporal expression dynamics of CCL17 across different disease stages require further clarification to define the optimal window for therapeutic intervention. Additionally, the safety of targeting the CCL17/CCR4 axis remains a core consideration: due to CCL17’s pleiotropic functions in tissue-specific immune tolerance, non-selective inhibition may disrupt physiological immune homeostasis, increase susceptibility to infections, or exacerbate comorbid inflammatory conditions such as atopic dermatitis and interstitial lung disease.

Future research should leverage cutting-edge technologies to elucidate the cell-specific and context-dependent mechanisms of CCL17. Single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics can be used to dissect the heterogeneous expression patterns of CCL17 and its receptors across different vascular lesions, cell subsets, and disease stages, thereby identifying key cellular crosstalk networks. Functional studies using conditional knockout mice will help distinguish the pathogenic and protective roles of CCL17, avoiding confounding effects associated with global gene ablation. Furthermore, translational research should focus on the development of precision-targeted strategies, including highly selective CCL17 inhibitors (e.g., humanized monoclonal antibodies, structure-based small-molecule antagonists) to minimize cross-reactivity with CCL22 and lesion-specific drug delivery systems (e.g., vascular wall-homing nanoparticles) to enable therapeutic agents to accumulate at pathological sites while preserving the physiological functions of CCL17 in non-target tissues.

Meanwhile, clinical translation efforts need to address the specificity challenge of CCL17 as a biomarker. Given that CCL17 is also elevated in non-vascular diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, asthma, and COPD. Future studies should explore combinatorial biomarker panels to improve the diagnostic accuracy of pan-vascular diseases. Longitudinal studies are also required to evaluate whether serial monitoring of CCL17 levels can predict treatment responses to emerging therapies (e.g., SGLT2 inhibitors, anti-inflammatory agents) and guide personalized treatment adjustments.

In summary, CCL17 serves as a central hub in the inflammatory networks driving pan-vascular diseases, with great potential as both a diagnostic biomarker and a therapeutic target. Integrating preclinical and clinical research, advanced technological approaches, and precision medicine strategies to address existing knowledge gaps is crucial for fully unlocking the translational potential of CCL17, ultimately improving the diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive outcomes of pan-vascular diseases and their associated complications. In the coming years, it is expected that our understanding of this multifunctional chemokine will be further deepened, and these insights will be translated into tangible clinical benefits for a large number of patients.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The Graphical Abstract was created with BioRender.com (2025). Available from: https://biorender.com/odwo9t9.

Authors’ contributions

Analyzed all the literature and prepared the manuscript: Yan W, Zhang H, Zheng P

Conceived the study and revised the manuscript: Dai Y

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project (2024ZD0537800). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of interest

Dai Y. is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Vessel Plus. Dai Y. was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Zhou X, Yu L, Zhao Y, Ge J. Panvascular medicine: an emerging discipline focusing on atherosclerotic diseases. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:4528-31.

2. Wong M, Dai Y, Ge J. Pan-vascular disease: what we have done in the past and what we can do in the future? Cardiol Plus. 2024;9:1-5.

3. Ruf B, Greten TF, Korangy F. Innate lymphoid cells and innate-like T cells in cancer - at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2023;23:351-71.

4. Imai T, Yoshida T, Baba M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Yoshie O. Molecular cloning of a novel T cell-directed CC chemokine expressed in thymus by signal sequence trap using Epstein-Barr virus vector. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21514-21.

6. Nakanishi T, Inaba M, Inagaki-Katashiba N, et al. Platelet-derived RANK ligand enhances CCL17 secretion from dendritic cells mediated by thymic stromal lymphopoietin. Platelets. 2015;26:425-31.

7. Catherine J, Roufosse F. What does elevated TARC/CCL17 expression tell us about eosinophilic disorders? Semin Immunopathol. 2021;43:439-58.

8. Stutte S, Quast T, Gerbitzki N, et al. Requirement of CCL17 for CCR7- and CXCR4-dependent migration of cutaneous dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8736-41.

9. Yan YH, Yu F, Zeng C, Cao LH, Zhang Z, Xu QA. CCL17 combined with CCL19 as a nasal adjuvant enhances the immunogenicity of an anti-caries DNA vaccine in rodents. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37:1229-36.

10. Schade DS, Shey L, Eaton RP. Cholesterol review: a metabolically important molecule. Endocr Pract. 2020;26:1514-23.

11. Minelli S, Minelli P, Montinari MR. Reflections on atherosclerosis: lesson from the past and future research directions. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:621-33.

13. Weber C, Zernecke A, Libby P. The multifaceted contributions of leukocyte subsets to atherosclerosis: lessons from mouse models. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:802-15.

14. Shortman K, Naik SH. Steady-state and inflammatory dendritic-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:19-30.

15. Weber C, Meiler S, Döring Y, et al. CCL17-expressing dendritic cells drive atherosclerosis by restraining regulatory T cell homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2898-910.

16. Imai T, Baba M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Takagi S, Yoshie O. The T cell-directed CC chemokine TARC is a highly specific biological ligand for CC chemokine receptor 4. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15036-42.

17. Döring Y, van der Vorst EPC, Yan Y, et al. Identification of a non-canonical chemokine-receptor pathway suppressing regulatory T cells to drive atherosclerosis. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2024;3:221-42.

18. Zhang Y, Tang X, Wang Z, et al. The chemokine CCL17 is a novel therapeutic target for cardiovascular aging. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:157.

19. Raffort J, Lareyre F, Clément M, Hassen-Khodja R, Chinetti G, Mallat Z. Monocytes and macrophages in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:457-71.

20. Ye Y, Yang X, Zhao X, et al. Serum chemokine CCL17/thymus activation and regulated chemokine is correlated with coronary artery diseases. Atherosclerosis. 2015;238:365-9.

21. Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PW, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2007;297:1197-206.

22. Marchant DJ, Boyd JH, Lin DC, Granville DJ, Garmaroudi FS, McManus BM. Inflammation in myocardial diseases. Circ Res. 2012;110:126-44.

23. Feng G, Bajpai G, Ma P, et al. CCL17 aggravates myocardial injury by suppressing recruitment of regulatory T cells. Circulation. 2022;145:765-82.

24. Shi L, Li G, Hou N, et al. APOB and CCL17 as mediators in the protective effect of SGLT2 inhibition against myocardial infarction: Insights from proteome-wide mendelian randomization. Eur J Pharmacol. 2024;976:176619.

25. Schnelle M, Leha A, Eidizadeh A, et al. Plasma biomarker profiling in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction before and after spironolactone treatment: results from the aldo-DHF trial. Cells. 2021;10:2796.

26. Zhang Y, Ye Y, Tang X, et al. CCL17 acts as a novel therapeutic target in pathological cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. J Exp Med. 2022:219.

27. Cheng P, Wang X, Liu Q, et al. LuQi formula attenuates Cardiomyocyte ferroptosis via activating Nrf2/GPX4 signaling axis in heart failure. Phytomedicine. 2024;125:155357.

28. Wang X, Liu Q, Cheng P, et al. LuQi formula ameliorates pressure overload-induced heart failure by regulating macrophages and regulatory T cells. Phytomedicine. 2025;141:156527.

29. Achim A, Péter OÁ, Cocoi M, et al. Correlation between coronary artery disease with other arterial systems: similar, albeit separate, underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023;10:210.

30. Kollikowski AM, Schuhmann MK, Nieswandt B, Müllges W, Stoll G, Pham M. Local leukocyte invasion during hyperacute human ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2020;87:466-79.

31. Alhadidi QM, Bahader GA, Arvola O, Kitchen P, Shah ZA, Salman MM. Astrocytes in functional recovery following central nervous system injuries. J Physiol. 2024;602:3069-96.

32. Giannoni P, Badaut J, Dargazanli C, et al. The pericyte-glia interface at the blood-brain barrier. Clin Sci. 2018;132:361-74.

33. Dargazanli C, Blaquière M, Moynier M, et al. Inflammation biomarkers in the intracranial blood are associated with outcome in patients with ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2025;17:159-66.

34. Farris BY, Monaghan KL, Zheng W, et al. Ischemic stroke alters immune cell niche and chemokine profile in mice independent of spontaneous bacterial infection. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2019;7:326-41.

35. Matsushita K, Ballew SH, Wang AY, Kalyesubula R, Schaeffner E, Agarwal R. Epidemiology and risk of cardiovascular disease in populations with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18:696-707.

36. Anders HJ, Vielhauer V, Schlöndorff D. Chemokines and chemokine receptors are involved in the resolution or progression of renal disease. Kidney Int. 2003;63:401-15.

37. Furuichi K, Kaneko S, Wada T. Chemokine/chemokine receptor-mediated inflammation regulates pathologic changes from acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13:9-14.

40. Lebherz-Eichinger D, Klaus DA, Reiter T, et al. Increased chemokine excretion in patients suffering from chronic kidney disease. Transl Res. 2014;164:433-43.e1.

41. Cox KJ, Parshall MB, Hernandez SHA, Parvez SZ, Unruh ML. Symptoms among patients receiving in-center hemodialysis: A qualitative study. Hemodial Int. 2017;21:524-33.

42. Spencer RH, Kilfeather SA, Lee E, et al. Systemic inflammatory markers correlate with chronic kidney disease-associated pruritus and response to treatment. J Invest Dermatol. 2026;146:175-83.e4.

43. Napolitano M, Fabbrocini G, Ruggiero A, Marino V, Nocerino M, Patruno C. The efficacy and safety of abrocitinib as a treatment option for atopic dermatitis: a short report of the clinical data. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021;15:1135-47.

44. Thijs J, Krastev T, Weidinger S, et al. Biomarkers for atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15:453-60.

45. Li Y, Bonner MR, Browne RW, et al. Responses of serum chemokines to dramatic changes of air pollution levels, a panel study. Biomarkers. 2019;24:712-9.

46. Nukui Y, Yamana T, Masuo M, et al. Serum CXCL9 and CCL17 as biomarkers of declining pulmonary function in chronic bird-related hypersensitivity pneumonitis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0220462.

47. Otsubo Y, Fujita Y, Ando Y, Imataka G, Yoshihara S. Elevated serum TARC/CCL17 levels associated with childhood interstitial lung disease with SFTPC gene mutation. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2022;57:1820-2.

48. Feng G, Zhu C, Lin CY, et al. CCL17 Protects against viral myocarditis by suppressing the recruitment of regulatory T cells. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:e028442.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].