Gender-affirming rhinoplasty - critical analysis of outcomes using the standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey (SCHNOS)

Abstract

Aim: Gender-affirming rhinoplasty is a key component of facial gender-affirming surgery, aiming to align nasal aesthetics and function with a patient’s gender identity. While there has been a strong emphasis on the cosmetic outcomes of this procedure, rhinoplasty is also intended to improve nasal function. Few studies have assessed functional outcomes in this population using validated, patient-reported measures. This study aims to evaluate changes in nasal function and cosmetic satisfaction using the Standardized Cosmesis and Health Nasal Outcomes Survey (SCHNOS) in patients undergoing gender-affirming rhinoplasty.

Methods: A retrospective cohort of 20 patients (all facial feminization) who underwent gender-affirming rhinoplasty at a tertiary academic center was analyzed. SCHNOS-Obstruction (SCHNOS-O) and SCHNOS-Cosmesis (SCHNOS-C) scores were collected preoperatively and at approximately 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. Paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to compare pre- and postoperative scores, with subgroup analyses performed using analysis of variance. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results: Statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in SCHNOS-C scores were observed at 3, 6, and 12 months post-operatively, compared to pre-operatively (P < 0.05). Among the subgroup of patients with baseline nasal obstruction, a statistically and clinically significant reduction in score was seen at 6 months post-operatively compared to baseline (P < 0.05). Patients without nasal obstruction at presentation did not show a worsening SCHNOS-O score at any post-operative timepoint.

Conclusion: Gender-affirming rhinoplasty is associated with significant improvements in aesthetic satisfaction as measured by SCHNOS-C scores, with significant improvements in nasal function seen among those patients with nasal obstruction on presentation. These findings support the use of validated, patient-centered tools in outcome assessment and highlight the need for further research to optimize both functional and cosmetic results in gender-affirming rhinoplasty.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Gender-affirming surgery is a vital component of care for transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Facial gender affirming procedures - including rhinoplasty - play a central role in supporting gender congruence and overall well-being. Current literature demonstrates the significant psychosocial impact of gender-affirming facial surgery with reductions in gender dysphoria and improvements in mental health[1-4]. The nose specifically serves as a key central facial landmark that is critical in gender perception, and gender-affirming rhinoplasty is frequently sought out by transgender patients as part of facial feminization surgery[5-7]. In this population, rhinoplasty has been shown to independently predict improvements in anxiety, depression, and social isolation even after controlling for other gender-affirming interventions[3,7,8]. Despite growing demand and recognition of the importance of facial gender-affirming surgery, the literature still lacks robust outcome data - particularly those incorporating validated, patient-reported outcome measures that assess both cosmetic and functional domains.

The Standardized Cosmesis and Health Nasal Outcomes Survey (SCHNOS) is a patient-reported outcome tool validated for assessment of both functional and cosmetic outcomes in patients undergoing rhinoplasty[6,9-11]. Current studies on gender-affirming rhinoplasty focus primarily on surgical technique and visual outcomes, with limited emphasis on patient-centered metrics. There is a need for more rigorous, standardized outcome assessments of facial gender-affirming surgery outcomes using validated tools, especially in the setting of rhinoplasty, where the goals may differ from those of traditional cosmetic or functional nasal surgery. In particular, it is key to include both objective and subjective outcome measures to better understand the true impact of these procedures on quality of life.

Research that helps characterize the unique needs and outcomes of gender-affirming rhinoplasty is essential to improving surgical planning, individualizing care, and advocating for access to these medically necessary procedures. By systematically analyzing both functional and cosmetic outcomes using the SCHNOS tool, this study seeks to address a significant gap in the literature and contribute to the development of evidence-based approaches in gender-affirming surgical care.

METHODS

This retrospective cohort study included patients who underwent gender-affirming rhinoplasty performed by facial plastic surgeons at the University of Virginia Health System between January 1, 2022, and June 1, 2025. A total of 28 patients who underwent gender-affirming rhinoplasty, all seeking facial feminization, were identified. Twenty of the 28 patients were included in the data analysis, as they had completed the SCHNOS preoperatively and at one or more postoperative time points. All patients had their procedures covered under gender-affirming care by their insurance providers. As this is a retrospective study, informed consent was not required for study participation. Pre- and post-operative photos are shown with written patient consent. This study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Virginia Health System.

Demographic and clinical data were extracted from the electronic medical record [Table 1]. SCHNOS-Obstruction (SCHNOS-O) and SCHNOS-Cosmesis (SCHNOS-C) scores were collected at baseline (preoperative) and postoperatively at approximately 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year, when available. These timepoints were selected to capture early and longer-term outcomes as consistent with the established timeline of rhinoplasty recovery and follow-up intervals[12]. The two domains of the SCHNOS score were analyzed separately as primary outcome measures.

Summary of total patient demographics

| Category | Variable | n | Proportion |

| Patients | Total | 20 | 100% |

| Race | African American | 2 | 10.00% |

| Asian | 1 | 5.00% | |

| Hispanic | 3 | 15.00% | |

| White | 14 | 70.00% | |

| Age (years) | 18-29 | 5 | 25.00% |

| 30-44 | 8 | 40.00% | |

| 45-64 | 5 | 25.00% | |

| ≥ 65 | 2 | 10.00% | |

| Gender | Female | 20 | 100.00% |

| Male | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Insurance | Medicaid | 12 | 60.00% |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 2 | 10.00% | |

| Private | 6 | 30.00% | |

| Surgical maneuvers | Nasal valve repair | 20 | 100% |

| Spreader grafts | 14 | 70% | |

| Alar rim grafts | 3 | 15% | |

| Batten grafts | 2 | 10% | |

| Lateral crural flaring sutures | 2 | 10% | |

| Lateral crural strut grafts | 1 | 5% |

The primary outcome was the change in SCHNOS-O and SCHNOS-C scores from preoperative baseline to the latest available postoperative time point. Additional data collected was the use of specific surgical maneuvers that serve to widen the nose: spreader grafts, batten grafts, and lateral crural strut grafts. These variables were considered for secondary analyses to evaluate potential detrimental effects on cosmesis in the SCHNOS-C domain associated with maneuvers intended to improve nasal function as measured by the SCHNOS-O domain.

Each SCHNOS domain ranges from 0-100 (0 = no symptoms). There is no established normative value for this score separating normal controls from patients seeking rhinoplasty. However, in a control sample from the Dutch validation cohort, median SCHNOS-O scores in cisgender populations were identified to be 10 [IQR 0-30], with SCHNOS-C = 0 [interquartile range (IQR) 0-10]. For context regarding the clinical significance of results, previously published minimum clinically important differences (MCIDs) for the SCHNOS have been estimated at 28 points for the obstruction domain (SCHNOS-O) and 18 points for the cosmetic domain (SCHNOS-C)[13].

Statistical analyses were performed using paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, depending on the distribution of the data, to compare pre- and postoperative SCHNOS-O and SCHNOS-C scores at different timepoints. Subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate the association between specific surgical maneuvers and changes in outcome scores. Patients were further analyzed based on those who received additional, same-day facial feminization procedures and those who did not. SCHNOS-C scores were then evaluated and compared between these two groups.

Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. A linear mixed-effects model evaluated overall timepoint effects. One-sided paired t-tests were conducted for post-hoc testing for robustness and were used for normally distributed data; otherwise, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied. A Holm-Bonferroni correction was applied to address family-wise error for multiple comparisons within each outcome domain (SCHNOS-C and SCHNOS-O).

One-sided t-tests were justified for SCHNOS-C based on the expectation that gender-affirming rhinoplasty is designed to improve nasal cosmetics. In contrast, SCHNOS-O was tested with two-sided analyses, recognizing that in some cases, technical factors, healing variability, or focus on aesthetic changes (typically reducing the nasal size) may compromise the expected improvement in obstruction outcomes.

All statistical tests were conducted with significance set at P < 0.05. Analyses were performed using R version 4.5.1.

RESULTS

Patient cohort

A total of 28 patients who underwent gender-affirming rhinoplasty were included in this study, with data points ranging from August 2021 to May 2025. Eight patients were excluded from the final analysis due to incomplete data (missing either preoperative or postoperative SCHNOS scores). The final analytic cohort comprised 20 patients. Baseline demographics and procedural breakdown are provided in Table 1. SCHNOS scores were collected and categorized into groups consisting of the preoperative baseline and 3-, 6-, and 12-month postoperative intervals. Furthermore, to assess SCHNOS-O score timepoints in greater detail, data were pooled into short-term (< 6 months) and long-term (> 6 months) outcomes. See Figure 1 for a representative intraoperative Gunter Diagram and Figure 2 for pre- and postoperative patient photos.

Figure 2. Pre- and post-operative feminization rhinoplasty photos: (A) Frontal view; (B) Basal view; (C) Bird’s-eye view; (D) Left oblique view; (E) Left profile view; (F) Right oblique view; and (G) Right profile view. Notable post-operative changes include a more refined and even middle vault, narrowed bony dorsum, creation of a supra-tip break, nasal tip refinement and elevation, and reduction of the alar base and sill for tip refinement and improved tip-alar harmony.

Changes in SCHNOS scores over time

Linear mixed models (LMMs) were used to assess differences across time points within the full cohort of samples (n = 20). Post-hoc estimated marginal means analysis was conducted using a linear mixed-effects model, controlling for random effects by patient.

The full cohort demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in SCHNOS-C scores at all postoperative timepoints compared to baseline. Using the previously defined minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 18 for the SCHNOS-C, all postoperative time frames demonstrated clinically significant improvements in SCHNOS-C scores[12]. No significant differences were observed between post-operative intervals (3 months vs. 6 months: P = 0.41; 6 months vs. 12 months: P = 0.52), suggesting that satisfaction mainly occurred within the first 3 months and persisted throughout the first year.

SCHNOS-O scores also showed a statistically significant reduction from baseline to 6 months postoperatively. Significant decreases in SCHNOS-O were achieved in the 3-6 month timeframe, with Airflow decreasing 1.34 [t (43.6) = 2.81, P < 0.05)], congestion decreasing an average of 0.96 [t (40.4) = 2.833, P < 0.05], and a significant effect of time on obstruction scores [t (29) = 5.46, P < 0.001] for obstruction, with a statistically significant reduction between preoperative and 6-month scores [estimate = 1.14 ± 0.40, 95% confidence interval (CI) (0.04, 2.24), t (41.5) = 2.86, P = 0.0397].

No statistically significant differences were observed between baseline and 3 months (-13.1, P = 0.23) or 12 months (-14.3, P = 0.9573), nor between these postoperative timepoints (P > 0.05, Holm-adjusted). The improvement in SCHNOS-O at the 6-month mark of 23.9 points on average fell short of the defined MCID of 28 points of improvement for this scale[12]. When pooled into pre-operative, early (≤ 6 months), and late

All results relating to the full cohort LMM can be found in Figure 3, Tables 2 and 3.

Figure 3. Linear Mixed Model analysis of SCHNOS scores over time periods. *: 0.01 < P < 0.05; **: 0.001< P < 0.01; ***: 0.0001 < P < 0.001; ****: P < 0.0001. SCHNOS: Standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey; PREOP: pre-operation; 3MO: within 3 months; 6MO: within 6 months; 12MO: within 12 months; ns: non-significant.

Overview of linear mixed model statistics (Full cohort, 20 samples)

| SCHNOS-C | |||||

| Time point | Mean ± SD (n) | Estimate vs. Pre-Op | 95%CI | SE | P (Holm-Adj) |

| Preoperative | 70.9 ± 22.2 (27) | - | - | - | - |

| 3 months | 31.8 ± 32.4 (19) | -39.6 | (-59.2, -20.0) | 7.07 | < 0.0001 |

| 6 months | 17.9 ± 24.6 (13) | -52.8 | (-75.4, -30.3) | 8.16 | < 0.0001 |

| 12 months | 4.44 ± 7.70 (3) | -63.2 | (-105.2, -21.1) | 15.3 | 0.0005 |

| Cisgender control | 0.0 | - | [0.0, 10.0] | - | - |

| SCHNOS-O | |||||

| Time point | Mean ± SD (n) | Estimate vs. Pre-Op | 95%CI | SE | P (Holm-Adj) |

| Preoperative | 40.7 ± 36.7 (27) | - | - | - | - |

| 3 months | 28.4 ± 28.9 (19) | -13.1 | (-30.7, 4.59) | 6.36 | 0.2325 |

| 6 months | 17.3 ± 18.0 (13) | -23.9 | (-44.5, -3.35) | 7.43 | 0.0149 |

| 12 months | 10.0 ± 13.2 (3) | -14.3 | (-53.5, 24.9) | 14.2 | 0.9573 |

| Cisgender control | 10.0 | - | [0.0, 30.0] | - | - |

SCHNOS-O scores alternative stratification (Full cohort, 20 samples)

| SCHNOS-O mean ± SD (n) | Estimate vs. Pre-Op (O) | 95%CI | SE (O) | P (O, Holm-Adj) | |

| Preoperative | 40.7 ± 36.7 (27) | - | - | - | - |

| Early (< 6 months) | 25.3 ± 31.3 (24) | -15.23 | (-30.5, 0.0281) | 6.12 | 0.0451 |

| Late (> 6 months) | 19.3 ± 29.25 (11) | -21.26 | (-42.2, -0.3528) | 8.41 | 0.0451 |

Pre-existing functional issues (pre-operative SCHNOS > 0) cohort

To understand SCHNOS scores in a more nuanced context, patients were categorized into two cohorts: those with (SCHNOS-O > 0) and without (SCHNOS-O = 0) baseline obstructions. Separate LMMs were performed for both cohorts.

For those with elevated SCHNOS-O scores (n = 17), SCHNOS-C scores improved by both a statistically and clinically significant amount, utilizing the defined SCHNOS-C MCID of 18 points for improvement on this scale. Similar to the full cohort, no significant differences were observed between post-operative time points (3 months vs. 6 months: P = 0.43; 6 months vs. 12 months: P = 1.0). Among the subset of patients with initial nasal obstruction, SCHNOS-O demonstrated both clinical and statistical improvement at 6 months post-operatively using the SCHNOS-O MCID (28)[11]. This indicates that patients with pre-operative nasal obstruction had clinically meaningful improvements in their obstruction scores. As in the full cohort LMM, discrepancies in the 6-month and 12-month post-operative results may be due to lower power from the small sample size (n = 2), as many patients were lost to follow-up. These data points are shown in Table 4.

Longitudinal SCHNOS scores in the elevated SCHNOS-O cohort

| SCHNOS-C | |||||

| Time point | Mean ± SD (n) | Estimate vs. Pre-Op | 95%CI | SE | P (Holm-Adj) |

| Preoperative | 77.3 ± 15.2 (22) | - | - | - | - |

| 3 months | 32.7 ± 34.8 (16) | -45.1 | (-65.3, -24.9) | 6.28 | < 0.0001 |

| 6 months | 16.4 ± 26.2 (11) | -60.9 | (-84.3, -37.6) | 7.29 | < 0.0001 |

| 12 months | 6.67 ± 9.43 (2) | -65.3 | (-114.5, -16.2) | 3.68 | 0.0027 |

| SCHNOS-O | |||||

| Time point | Mean ± SD (n) | Estimate vs. Pre-Op | 95%CI | SE | P (Holm-Adj) |

| Preoperative | 50.0 ± 34.4 (22) | - | - | - | - |

| 3 months | 33.4 ± 28.9 (16) | -16.6 | (-37.1, 3.92) | 7.30 | 0.1488 |

| 6 months | 18.6 ± 18.9 (11) | -31.6 | (-55.5, -7.65) | 8.54 | 0.0046 |

| 12 months | 15.0 ± 14.1 (2) | -19.5 | (-70.6, 31.7) | 18.4 | 0.8889 |

No pre-existing functional issues (pre-operative SCHNOS = 0) cohort

Data points for SCHNOS scores in the cohort without initial nasal obstruction were sparse due to the limited patient sample (n = 3). As such, any statistical or clinical interpretations should be made with caution due to the low power of the LMM.

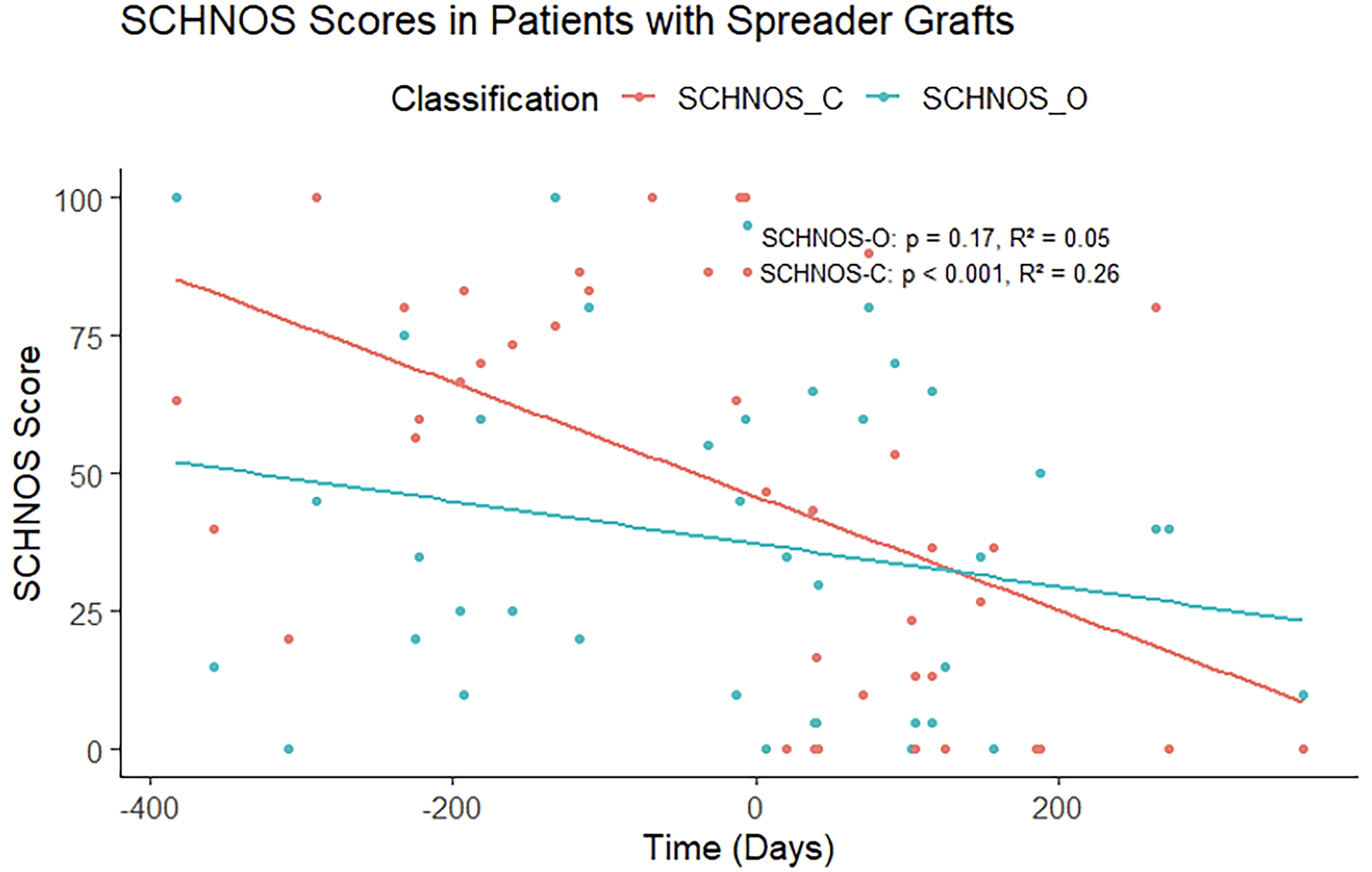

Surgical maneuvers and SCHNOS scores

To analyze the effectiveness of valve repair in treating obstruction, scores were stratified based on the type of valve repair performed during the procedure. Fourteen patients received spreader grafts, two patients received batten grafts, and only one patient received lateral crural strut grafts.

A Shapiro-Wilk test indicated normality in the maneuvers dataset (W = 0.96, P = 0.77), and Levene’s test confirmed homogeneity of variance [F (3, 8) = 1.26, P = 0.35], supporting both normality assumptions and assumption of equal variances for analysis of variance (ANOVA).

A multi-way ANOVA was conducted to assess whether the use of batten grafts, spreader grafts, or lateral crural strut grafts was associated with changes in SCHNOS scores (ΔSCHNOS). Among these, only the use of spreader grafts was associated with statistically significant changes in SCHNOS-O score [F (1,8) = 7.91, P = 0.023]. Patients who received spreader grafts demonstrated a greater reduction in SCHNOS-O scores than those who did not - after adjusting for other maneuvers - with an adjusted mean difference of -38.2 points (95%CI: -86.5 to -18.5, P = 0.046). No significant associations between changes in SCHNOS-C were found between any of the three maneuvers.

While this supports SCHNOS-O improvements of spreader grafts, the small sample size of lateral crural strut grafts (n = 1) and batten grafts (n = 2) substantially reduces statistical power and increases the risk of Type II errors. Thus, despite meeting ANOVA assumptions, these findings should be considered exploratory. Descriptive statistics are included in Table 5.

Nasal valve repair multi-way ANOVA

| ΔSCHNOS-O mean ± SD (n) | P (O) | Mean difference ± SE (P) | |

| Batten grafts | -38.1 ± 27.5 (14) | 0.32 | - |

| Spreader grafts | -40.0 ± 28.3 (2) | 0.023 | 38.2 ± 16.2 (0.046) |

| Lateral crural struts | -65 (1) | 0.25 | - |

| No nasal valve repair | 6.25 ± 9.46 (6) | - | - |

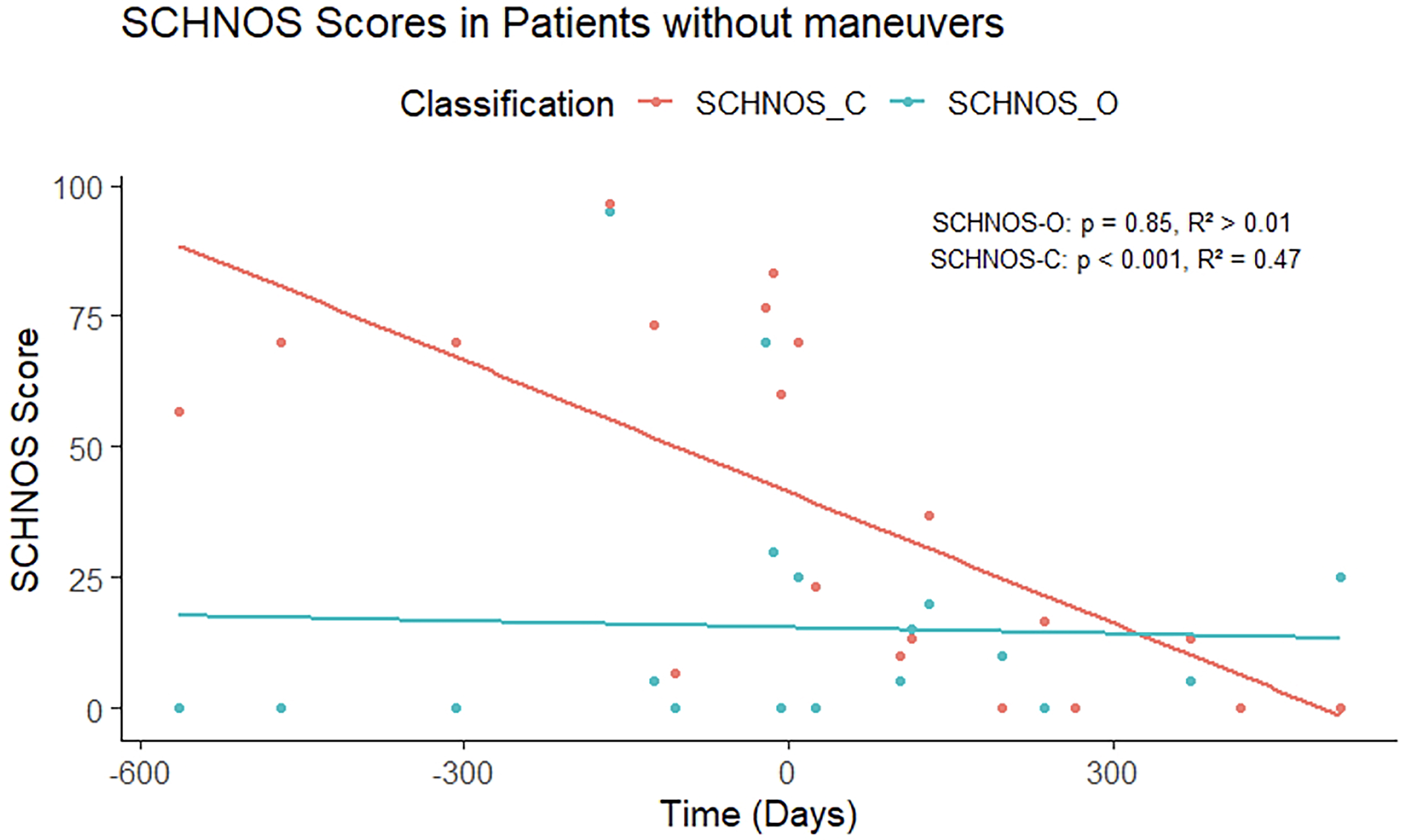

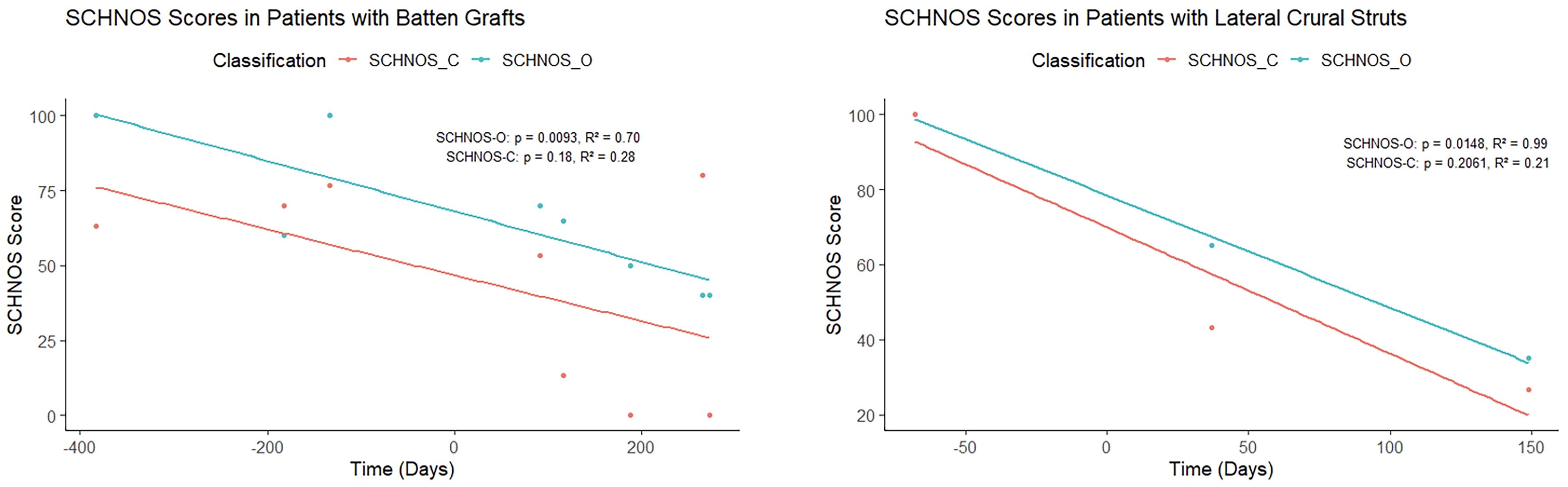

Trends in SCHNOS scores for patients whose surgeries included or did not include the above surgical maneuvers can be seen in Figures 3-6.

Figure 4. SCHNOS scores in patients without nasal valve repair. SCHNOS: Standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey.

Figure 5. SCHNOS scores for lateral crural struts and batten graft. SCHNOS: Standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey.

Analyzing SCHNOS in patients with and without concomitant procedures

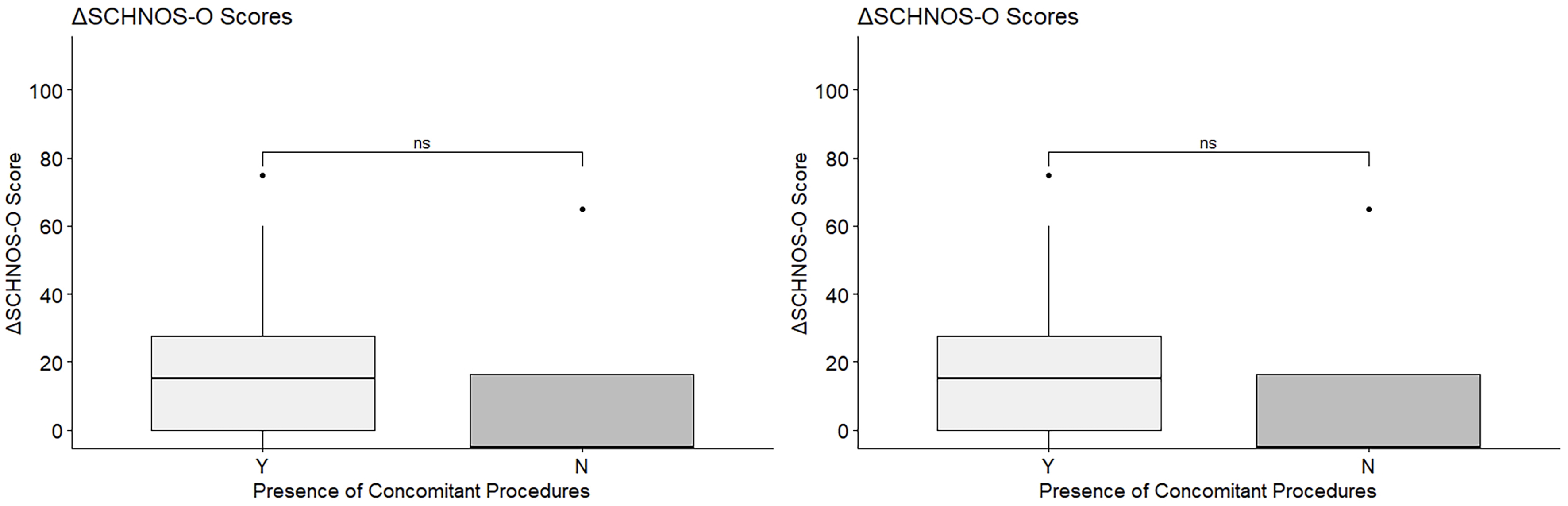

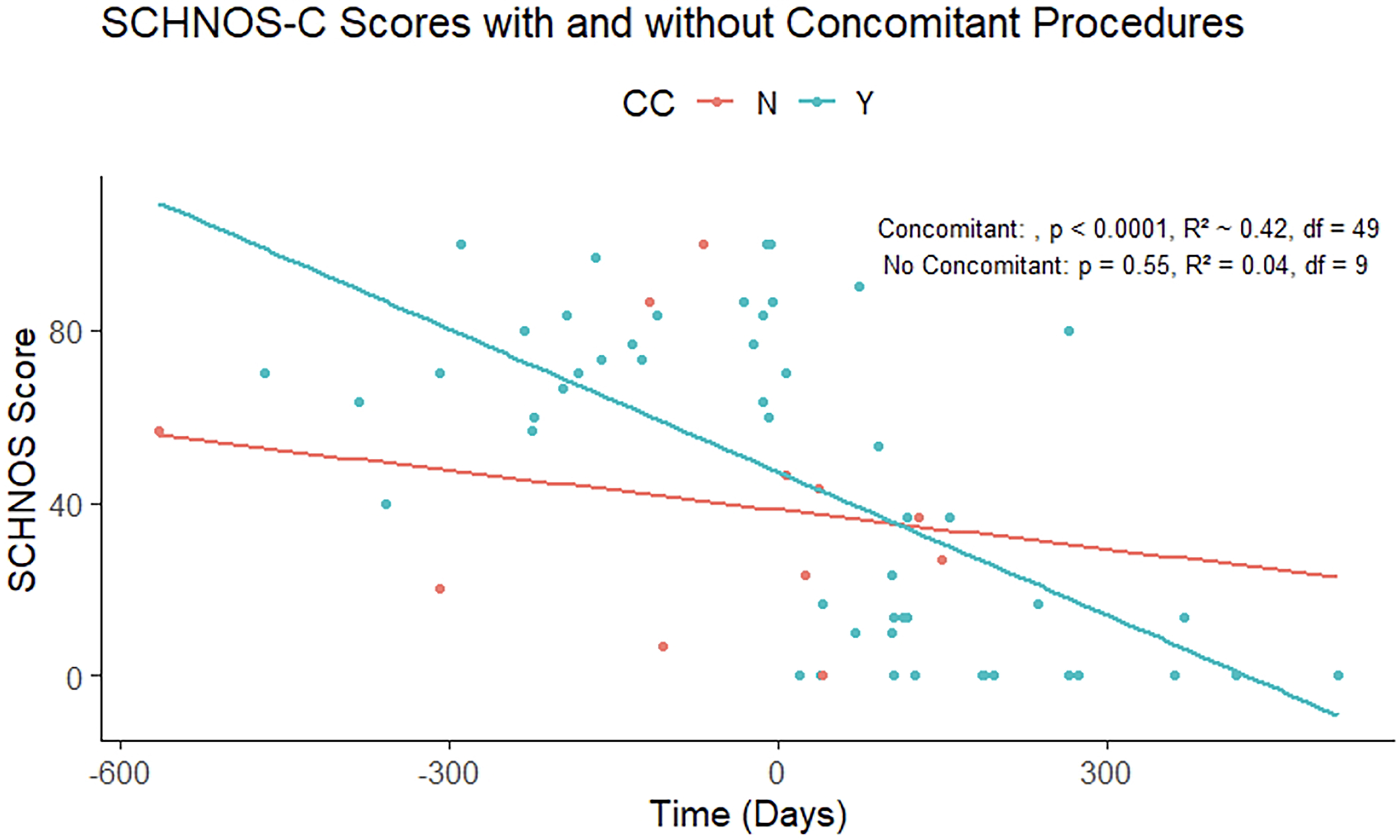

Analyzing scores over time, patients with concomitant procedures were observed to have a moderate temporal association [Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R2) = 0.42, P < 0.0001] with an improvement in SCHNOS-C scores, while those who did not have concomitant procedures demonstrated minimal association between SCHNOS-C and time postoperatively (R2 = 0.040, P = 0.55). Moreover, no significant difference via t-test was detected in the difference in SCHNOS scores in patients with and without concomitant procedures [SCHNOS-O, degrees of freedom (df) = 3.69, P = 0.62, SCHNOS-C, df = 4.23, P = 0.837] [Figures 7 and 8]. This change may potentially reflect the overall influence of concomitant procedures on patients’ overall satisfaction with rhinoplasty outcomes.

Figure 7. ΔSCHNOS with (Y) and without (N) concomitant procedures. SCHNOS: Standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey.

Figure 8. SCHNOS scores with (Y) and without (N) concomitant (CC) procedures. SCHNOS: Standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey.

To assess whether insurance coverage influenced patient-reported outcomes (PROMs), a one-way ANOVA was performed with ΔSCHNOS-C as the dependent variable and insurance type as the factor. No significant effect of insurance status was observed [F (3, 15) = 0.90, P = 0.47], indicating that postoperative improvement in SCHNOS-C did not differ among payer groups.

DISCUSSION

In the context of gender-affirming care, feminization rhinoplasty typically involves dorsal reduction, tip refinement with increased rotation, and narrowing of the nasal bones to achieve a more feminine nasal contour, aligning with established anthropometric and aesthetic goals[4,8,14]. However, a recent scoping review highlights a critical gap: while PROMs such as SCHNOS are widely used, none have been specifically validated for gender-affirming rhinoplasty populations, despite their unique needs and expectations[10].

We conducted a retrospective study evaluating SCHNOS-C and SCHNOS-O scores in patients undergoing feminization rhinoplasty, which demonstrates significant improvement in SCHNOS-C scores at all postoperative timepoints. In contrast, significant improvement in SCHNOS-O scores was only observed between 3 and 6 months after surgery, suggesting a delayed but meaningful functional benefit. Notably, patients with elevated preoperative SCHNOS-O scores exhibited a linear decrease in obstruction symptoms over time, while those with low baseline scores maintained stable, minimal levels of obstruction. This pattern aligns with prior data showing that SCHNOS-O and SCHNOS-C are sensitive to both functional and cosmetic changes after rhinoplasty, with improvements typically being sustained over time[9-11,15].

Unlike prior studies that demonstrate early and sustained SCHNOS-O improvements within 2-3 months post-rhinoplasty, our cohort did not reach statistical significance until the 3-6 month postoperative interval after correcting for multiple testing[10]. This likely reflects the small sample size (particularly in reference to the under-representation of patients with baseline obstructions at 12 months) and loss to follow-ups rather than a true absence of functional improvements. Pooling early and late postoperative intervals failed to yield significant differences, further emphasizing limited statistical power rather than an inconsistent clinical effect. Nevertheless, SCHNOS scores following GAR reached normative thresholds in cisgender populations.

Qualitative review of surgical maneuvers that widen the nose (batten grafts, lateral strut grafts, spreader grafts) revealed that, even when these techniques were employed to optimize airway function, patients still reported improvement in both SCHNOS-C and SCHNOS-O scores. This finding is clinically relevant, as it suggests that functional grafting - often necessary to prevent or correct airway compromise - does not preclude perceived cosmetic benefit in the context of feminization rhinoplasty when applied thoughtfully. This observation is consistent with the literature, which emphasizes the importance of balancing functional and aesthetic goals in rhinoplasty, particularly in gender-affirming populations[5].

Additionally, patients who underwent concomitant facial feminization, such as frontal sinus setback, hairline advancement, and genioplasty, appeared to have greater qualitative decreases in SCHNOS-C scores compared to those who had rhinoplasty alone. This trend suggests that global facial changes may positively influence self-perception of nasal cosmesis, supporting the concept that facial harmony and gender congruence are critical determinants of patient satisfaction. Indeed, some questions on the SCHNOS form incorporate features beyond the nose exclusively such as question 5 (decreased mood and self-esteem due to my nose) and question 9 (how well my nose suits my face). In these cases, improved overall facial gender harmony may go a long way toward overall improvements in mood and self-esteem and facial balance, creating a halo effect where patients who are overall more satisfied tend to rate their rhinoplasty outcome as more satisfying.

Gender-affirming rhinoplasty not only serves to modify nasal form and function, but is also critical to the psychosocial health for transgender and gender diverse patients[5,16,17]. Incongruence between gender identity and facial appearance, particularly that of the nose, can be a significant source of gender dysphoria which is associated with elevated rates of psychological distress, depression, and suicidality among this population[18]. Facial feminization surgery has, independently, been shown to predict improvements in global mental health in gender diverse patients, underscoring the central role of facial gender-affirming surgery in comprehensive care of such patients[8]. Strong associations between improved SCHNOS scores and reduction in appearance-related distress, enhanced patient satisfaction, and positive psychological impact following rhinoplasty have been demonstrated in the literature[19]. Therefore, favorable SCHNOS outcomes in patients undergoing gender-affirming rhinoplasty can be assumed to represent good psychosocial outcomes among these patients.

Our data further supports these assumptions, with analysis of mood and self-esteem related SCHNOS line item showing statistically significant decreases in psychosocial distress following gender affirming rhinoplasty. Question 5 on the SCHNOS survey asks patients to rate their level of “Decreased mood and self-esteem due to my nose”. Evaluation of responses for this question among the cohort showed significant post-operative improvements in mood and self-esteem compared to pre-operative values, with adjusted mean scores decreasing by an average of 2.44 points [t (45.8) = 5.62, P < .0001]. Moreover, perceived shape from the side (-2.95, P <0.0001), straightness (-2.38, P < 0.0001), suitability (-3.11, P < 0.0001), tip shape

Limitations

These findings represent the first reported use of SCHNOS as a comprehensive patient-reported outcome measure in gender-affirming rhinoplasty while also highlighting the need for further validation in this unique population. Limitations of this study include sample size and lack of survey data at all time points for each patient. The final population able to be analyzed was only 20 patients, which reduces the power of these results, especially when divided into subgroups. Of note, several patients were lost to follow-up over time, and the number of patients returning for their 12-month post-operative visit was quite small. Alongside this, power was further limited by the small number of patients with 12-month data, all of whom had minimal preoperative obstruction, which likely attenuated apparent long-term SCHNOS-O changes and explains the absence of statistical significance after Holm adjustment. This may introduce bias into the results, as we cannot determine whether those who returned had the same level of improvement as patients who did not return 1 year after surgery. Therefore, conclusions regarding SCHNOS-O scores at the 12-month post-operative interval should be interpreted with caution.

In addition, all of our patients underwent feminization rhinoplasty, and future research should explore the application of SCHNOS in masculinization rhinoplasty, where nasal widening and augmentation are often desired to achieve a more masculine appearance. Despite this small sample size and limited follow-up, the significant improvement seen in both nasal cosmesis and obstruction following gender-affirming rhinoplasty among these patients is compelling.

Although insurance type (private vs. Medicaid, Medicare/Medicaid) could theoretically influence postoperative satisfaction, exploratory analysis using a one-way ANOVA showed no significant difference in ΔSCHNOS-C between insurance groups [F (3, 15) = 0.90, P = 0.47]. Given the limited sample size, this variable was therefore treated as a potential but unmodeled confounder rather than included as a fixed effect.

Lastly, this study relied exclusively on patient-reported outcomes using the SCHNOS instrument. Objective assessments such as acoustic rhinometry, computed tomography (CT)-based volumetric analysis, or endoscopic grading of nasal valve area were not available due to the retrospective nature of data collection. To further delineate the relationship between anatomic correction and patient-perceived benefit in gender-affirming rhinoplasty, future prospective studies should incorporate objective airflow and imaging analyses alongside SCHNOS outcome measures. Despite the availability of objective or physician-graded assessments of nasal airflow, these measures have not been shown to consistently correlate with patient-perceived improvement in nasal airflow; therefore, they are not routinely used in clinical practice[20]. The American Academy of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery recommends using PROMs to assess both functional and aesthetic outcomes post-rhinoplasty[21]. Several studies demonstrate that while objective assessments (e.g., acoustic rhinometry, rhinomanometry, CT-measured nasal cavity volume) can document anatomical or physiological changes, these do not consistently align with patient-reported outcomes such as nasal obstruction or satisfaction[21,22]. However, objective assessments can be complementary to patient-reported outcome measures, and the lack of objective data in this study is certainly a limitation[23]. Future research evaluating both subjective and objective outcomes in a prospective fashion would significantly aid in understanding the results of gender-affirming rhinoplasty.

The ability of SCHNOS-C to capture patient-reported aesthetic outcomes across the gender spectrum will be essential for optimizing care and advancing the field of gender-affirming facial surgery. Equally, robust assessment and optimization of functional outcomes (via SCHNOS-O) remains essential to patient satisfaction and quality of life following rhinoplasty. As such, it is critical to balance both cosmetic and functional concerns when performing these procedures.

The present study demonstrates that feminization rhinoplasty leads to significant improvements in both cosmetic (SCHNOS-C) and functional (SCHNOS-O) patient-reported outcomes, with the most pronounced cosmetic changes observed by 3 months after surgery, remaining stable for 1 year post-operatively, and functional gains becoming significant by six months. These findings align with the broader literature, which shows that rhinoplasty in transfeminine patients reliably achieves high satisfaction and low complication rates, with dorsal reduction, tip refinement, and bony vault narrowing as key techniques for feminizing the nasal profile.

Surgical maneuvers such as composite dorsal hump resection, dorsal preservation, and the use of spreader grafts or other functional grafts are effective in balancing aesthetic and airway goals, supporting both the internal nasal valve and long-term tip stability. The use of adjunctive facial feminization procedures may further enhance patient-perceived nasal cosmesis, underscoring the importance of facial harmony in gender-affirming care.

Despite these advances, the medical literature highlights the need for further validation of PROMs such as SCHNOS in gender-affirming populations, as well as more research on outcomes in diverse patient groups. Overall, these results reinforce that both cosmetic and functional outcomes are crucial to patient satisfaction and quality of life after feminization rhinoplasty, and that evidence-based, individualized surgical planning is essential for optimal results.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the University of Virginia Department of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, Division of Facial Plastic Surgery, for their assistance in data collection. We also extend our gratitude to the patients who agreed to participate in this research and contributed to making this work possible.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the presented idea, devised the project, and supervised its execution: Oyer S

Assisted with data collection and manuscript editing: Brownlee B

Performed all data analysis and designed the figures: Chon S

Obtained institutional review board (IRB) approval, led the manuscript writing, and coordinated with the team to finalize the manuscript: Senderovich N

All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data is available and may be requested by email to the corresponding author.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of Virginia Health Institutional Review Board (IRB approval number 302546). The requirement for informed consent for study participation was waived by the IRB due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of pre- and postoperative photographs was obtained from all patients shown.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Akhavan AA, Sandhu S, Ndem I, Ogunleye AA. A review of gender affirmation surgery: what we know, and what we need to know. Surgery. 2021;170:336-40.

2. Ireland K, Hughes M, Dean NR. Do hormones and surgery improve the health of adults with gender incongruence? ANZ J Surg. 2025;95:864-77.

3. Park RH, Liu YT, Samuel A, et al. Long-term outcomes after gender-affirming surgery: 40-year follow-up study. Ann Plast Surg. 2022;89:431-6.

4. Wright JD, Chen L, Suzuki Y, Matsuo K, Hershman DL. National estimates of gender-affirming surgery in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2330348.

6. Bannister JJ, Juszczak H, Aponte JD, et al. Sex differences in adult facial three-dimensional morphology: application to gender-affirming facial surgery. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2022;24:S24-30.

7. Ellis M, Choe J, Barnett SL, Chen K, Bradley JP. Facial feminization: perioperative care and surgical approaches. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024;153:181e-93.

8. Caprini RM, Oberoi MK, Dejam D, et al. Effect of gender-affirming facial feminization surgery on psychosocial outcomes. Ann Surg. 2023;277:e1184-90.

9. Chen M, Cai S, Cai Z, et al. Translation, cultural adaptation, and validation of the standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey (SCHNOS) in Chinese. Aesthet Surg J. 2024;44:NP769-77.

10. Kandathil CK, Saltychev M, Patel PN, Most SP. Natural history of the standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey after rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:E116-23.

11. Takeuchi N, Miyawaki T, Otori N, et al. Translation, cultural adaptation, and validation of the Standardized Cosmesis and Health Nasal Outcomes Survey in Japanese (J-SCHNOS). J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2024;90:114-21.

12. Kandathil CK, Saltychev M, Abdelwahab M, Spataro EA, Moubayed SP, Most SP. Minimal clinically important difference of the standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39:837-40.

13. Pingnet L, Verkest V, Saltychev MM, Most SP, Declau F. Translation and validation of the standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey in Dutch. B-ENT. 2022;18:170-5.

14. Di Maggio MR, Nazar Anchorena J, Dobarro JC. Surgical management of the nose in relation with the fronto-orbital area to change and feminize the eyes’ expression. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30:1376-9.

15. Battista RA, Ferraro M, Piccioni LO, et al. Translation, cultural adaptation and validation of the standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey (SCHNOS) in Italian. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2022;46:1351-9.

16. Siringo NV, Berman ZP, Boczar D, et al. Techniques and trends of facial feminization surgery: a systematic review and representative case report. Ann Plast Surg. 2022;88:704-11.

17. Weissler JM, Chang BL, Carney MJ, et al. Gender-affirming surgery in persons with gender dysphoria. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:388e-96.

18. Eccles H, Abramovich A, Patte KA, et al. Mental disorders and suicidality in transgender and gender-diverse people. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2436883.

19. Losorelli S, Kimura KS, Wei EX, et al. Rhinoplasty outcomes in patients with symptoms of body dysmorphia. Aesthet Surg J. 2024;44:797-804.

20. Ishii LE, Tollefson TT, Basura GJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline: improving nasal form and function after rhinoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156:S1-30.

21. Edizer DT, Erisir F, Alimoglu Y, Gokce S. Nasal obstruction following septorhinoplasty: how well does acoustic rhinometry work? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:609-13.

22. Tugrul S, Dogan R, Hassouna H, Sharifov R, Ozturan O, Eren SB. Three-dimensional computed tomography volume and physiology of nasal cavity after septhorhinoplasty. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30:2445-8.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].