Strategic grafting in rhinoplasty

Abstract

This article provides an updated, comprehensive overview of grafting principles and techniques in reconstructive rhinoplasty. It reviews current options for grafting material and recent literature regarding the advantages and disadvantages of different graft sources. Various grafts, their indications, and recommended surgical techniques are also described in detail. Finally, the use of three-dimensional imaging and printing technology in reconstructive rhinoplasty is discussed.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Rhinoplasty is a commonly performed surgery, with approximately 352,000 cases performed in 2020 alone[1]. It is often done to address concerns regarding nasal function, cosmesis, or both. Functional rhinoplasties focus on improving nasal obstruction, which is usually due to lateral wall or nasal valve insufficiency[2]. The goal of cosmetic rhinoplasties is patient-dependent, but can include addressing nasal dorsum projection as well as tip projection and rotation. In either case, many of the surgical approaches to achieve these goals are based on utilizing grafts to augment or reshape a patient’s underlying structural anatomy. Strategic and reliable grafting techniques are key in most rhinoplasty cases. The surgeon’s choice of grafting materials and techniques is made difficult by the abundance of literature on these topics, including much controversy and debate.

This chapter initially reviews the current literature regarding sources of grafting materials, including alloplastic implants, autologous cartilage, and homografts. The remainder of the article discusses specific grafts in reconstructive rhinoplasty based on nasal anatomic region, recommended surgical techniques, and graft indications. It provides a strategic guide for surgeons as they navigate some of these more popular grafting techniques. The article also aims to discuss current controversies and research related to different grafts. Recent advances in three-dimensional (3D) imaging and printing technology and their roles in successful grafting outcomes in rhinoplasty are also discussed.

SOURCE OF GRAFT MATERIALS

Autografts are considered the gold standard for surgical implantation, as they have lower rates of extrusion and resorption, and no immunogenicity. However, use of autografts can also require multiple surgical sites and prolonged anesthesia time. Thus, a variety of other graft materials have been investigated for implantation in nasal reconstruction.

Xenografts

Xenografts, which are grafts harvested from non-human sources, include bovine cartilage and porcine small intestinal submucosa for repair of nasal septal perforations[3]. These were of interest historically, but are not generally recommended for nasal reconstruction due to the likelihood of significant inflammatory reactions and high rates of resorption[4].

Alloplastic implants

Common examples of alloplastic implants include plastic, silicone, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE; Gore-Tex, W. L. Gore and Associates Inc., Flagstaff, AZ), and porous high-density polyethylene (pHDPE; Medpor, Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI)[5]. The ideal alloplastic implant should be nontoxic and inert, but also easy to sculpt and sterilize. Use of alloplastic material can decrease operative time and is also beneficial when there is a paucity of autologous cartilage available. Silicone is commonly used in Asia for dorsal augmentation. It is nonporous and thus does not allow for tissue ingrowth. Instead, a thick capsule forms around the implant over time, which can be favorable for keeping implants in place but can also lead to capsule contracture[6]. Its nonporous nature theoretically decreases the risk of harboring bacteria, although Peled et al. found no difference in rates of infection between silicone, GoreTex, and Medpor[7]. Both GoreTex and Medpor are porous, allowing for tissue ingrowth and thus theoretically lower rates of extrusion compared to silicone. Indeed, Peled et al. found that the extrusion rate of ePTFE was significantly lower than that of silicone implants[7]. However, the extent of tissue ingrowth found in ePTFE and pHDPE may also make implant removal more difficult in cases of infection[8]. Complications of infection, extrusion, and shifting still tend to be higher in alloplastic implants compared to autografts[9].

Autologous cartilage

Septal cartilage

The advantage of utilizing septal cartilage is that it can be harvested from the same operative site, minimizing the risk of complications and operative time. Septal cartilage can be harvested through an open or closed rhinoplasty approach. It is essential that the L-strut is preserved (at least 1 cm wide) in order to prevent septal collapse. Septal cartilage will provide solid structural support to most noses, but the amount and quality of cartilage available may be insufficient in revision rhinoplasties or saddle nose patients[4,9].

Conchal cartilage

Auricular cartilage can be harvested from the conchal bowl as long as the antihelical rim is left intact[4]. Auricular cartilage is elastic-type cartilage (as opposed to septal and costal cartilage, which are both hyaline-type). This means it is abundant in elastin, resulting in better flexibility and resilience to pressure compared to septal or costal cartilage[10]. These same characteristics make conchal cartilage more difficult to use for grafts requiring greater rigidity[11]. Conchal cartilage may not be ideal in certain grafting techniques, such as caudal struts, as it has an inherent curvature that would need to be sculpted away. It is, however, ideal for alar reconstruction given its natural curvature. It requires a second operative site, though this is in close proximity to the primary site.

Costal cartilage

Costal cartilage is advantageous due to its strength and abundance; it is ideal in larger, more complex cases and in revision rhinoplasties. However, it can be considered for primary operations, especially for tip-shaping rhinoplasties in patients with preoperative weak tip support, thick skin, or history of septal trauma[12]. Its harvesting requires an additional surgical field with potential complications, including pneumothorax, mild chest contour deformities, and significant pain[13-15]. Cartilage can be harvested from ribs number 5 through 11; rib number 7 is most commonly used[11]. Of note, cartilaginous ribs calcify with time and may not be available for successful harvest in older patients. Prevalence of costal cartilage calcification increases with age, but has been shown to be present in individuals less than 40 years old to a non-negligible extent as well[16]. Preoperative CT imaging or formal ultrasound can be used to evaluate extent and patterns of calcification[17]. Park et al. recently described use of bedside ultrasound for evaluation of costal cartilage in the perioperative period[18].

Costal cartilage has been known to warp, perhaps making it a less desirable cartilage type for rhinoplasties, though warping rates in studies vary[13,14]. Gibson and Davis conducted a series of experiments to investigate the tendency of costal cartilage to warp[19]. They discovered warping is likely due to differences in tension between the outer and inner layers of cartilage. The intrinsic makeup of the inner cartilage zone results in a tendency to expand, a tendency that is kept in check by the outer zone. These forces, or “interlocked stresses,” are in balance with intact cartilage but are disrupted with unbalanced carving. The authors proposed the principle of balanced cross-sectional carving in order to minimize warping: if interlocked forces are kept in balance along the length of the graft, warping can be prevented. One approach is to solely harvest the central segment of costal cartilage for grafting, which entirely eliminates the outer layer contracting forces. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that peripherally cut pieces of cartilage warp significantly more than centrally cut pieces[20].

In 2013, Taştan et al. proposed a new method for carving costal cartilage: the oblique split method. Previously, cartilage was harvested along the long axis of the rib. With the oblique split method, grafts are obtained at an oblique angle to the long axis, usually 30 or 45 degrees. Opposing forces within the cartilage remain equally balanced with this technique, which minimizes warping even with thinner grafts. Another advantage is the increased amount of graft material one obtains from a single rib[21]. Wilson et al. found equivalent rates of warping when comparing costal cartilage harvested via the oblique split method vs. concentric carving methods[22].

Homografts

Homografts are harvested from cadavers and usually involve costal cartilage. Perichondrium is either removed or the graft is irradiated with gamma radiation, which eliminates the risk of antigenic response[4]. Some surgeons will also elect to use fresh frozen homologous costal cartilage (FFCC), which is not treated with radiation. Instead, FFCC is harvested from donors who meet very strict inclusion criteria. The graft is sterilized with surfactants and antibiotics, frozen to -40 to -80 °C, and packaged[23].

There is some debate regarding the degree of warping and resorption with irradiated homologous costal cartilage (IHCC) compared to autologous cartilage grafts. Welling et al. had found a significant 75% resorption rate with IHCC[24], although this study was not specific to rhinoplasties and included grafts in various locations in the head and neck region, including regions potentially under higher tension forces than those found in the nose. Wee et al. found a higher resorption rate with IHCC (30%) compared to autologous costal cartilage (3%), but no difference in warping rates between the two groups. The authors proposed that this higher resorption rate in their IHCC graft recipients may have been due to the irradiation used to prepare the grafts, resulting in lower chondrocyte viability[25]. One limitation of this study is its failure to age-match autologous cartilage with IHCC used. Given the histologic changes that occur in costal cartilage with age, a higher average donor age in the IHCC group may partially account for the higher resorption rates seen. In contrast to Wee et al., Karasik et al.’s survey of 134 facial plastic surgeons found the reported incidence of warping to be significantly higher in autologous grafts compared to homologous grafts. The authors did not find significant difference in resorption rates between the two groups[15,25].

Other studies have found no significant difference in rates of resorption or warping with IHCC compared to autologous cartilage. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, Vila et al. found no difference in rates of warping, resorption, infection, or revision surgery between homologous and autologous graft recipients for dorsal augmentation rhinoplasty[26]. Another recent review by Luan et al. confirmed low complication rates associated with IHCC, including 2.07% for warping, 1.77% for infection, 1.34% for resorption, and 2.13% for displacement[27]. A recent retrospective study by Jenny et al. showed no difference in complication rates between IHCC and autologous cartilage for use in cleft rhinoplasties[28]. However, given the controversy surrounding increased rates of resorption in IHCC, it is suggested that this cartilage source only be used for nonstructural grafts, so that if some resorption does occur it does not compromise nasal tip positioning[29]. Interestingly, Suh et al. investigated rates of complication with IHCC in different graft locations. They found that most complications with IHCC, including resorption, fragmentation, and warping, occurred with septal extension grafts (SEGs), likely secondary to the high tension forces the grafts were subjected to in order to provide nasal tip support[30]. Limitations of this study include a relatively short follow-up period of approximately 14 months and evaluation of complications based on physical exam findings and photographs alone. As the authors acknowledge, a long-term histologic study of IHCC graft complications in relation to graft location would be particularly interesting.

Some surgeons favor utilizing FFCC over IHCC due to concern that irradiation may weaken the structural integrity of IHCC grafts, potentially leading to higher resorption rates over time[31]. In a prospective, single-center study, Wan et al. found comparable complication rates between patients undergoing rhinoplasty using FFCC compared to autologous costal cartilage. Common complications included warping, resorption, infection, and scarring[32]. Hanna et al. noted a 2.1% postoperative infection rate with FFCC in their retrospective study, comparable to infection rates using autologous costal cartilage and IHCC. Notably, they reported no clinical signs of warping, resorption, or displacement of FFCC grafts[23].

Bone autografts

Split calvarial bone graft can be used to repair significant deformities, including saddle nose deformity[11]. The graft provides good stability and has low resorption rate. Rib grafts can also be used.

Use of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone with septal cartilage has also been described in certain grafting techniques. It can be used for septal batten grafts, described later, or strengthening of the L-strut to provide increased tip support. Once the nasal septal mucosa is separated from underlying cartilage and bone, the graft is harvested; care must be taken to leave at least a 1 cm wide L-strut in place. One concern with ethmoid bone harvest is the potential for skull base injury. The perpendicular plate of the ethmoid is thickest in the superior two-thirds of the bone, with thinning in the inferior one-third. Thus, the forces exerted during harvest are greatest superiorly[33]. Factors that may increase risk of skull base injury and subsequent cerebrospinal fluid leakage include osteotomy angle, depth of resection, and degree of septal deviation[34].

SPECIFIC GRAFTS BASED ON REGION AND THEIR INDICATIONS

Dorsum

Radix graft

The radix graft can be used to address a deep nasofrontal angle or prior overreduction of a dorsal hump. The ideal radix projects 9-14 mm from the corneal surface[35]. Septal or conchal cartilage is used to sculpt a graft that is thickest superiorly, with gradual thinning inferiorly in order to create a natural transition into the nasal dorsum. The lateral edges should be gently curved. The graft is then placed into a subperiosteal pocket beneath the procerus muscle. Importantly, the graft should be placed in a more superior position than its planned final location, as the procerus muscle tends to push the graft inferiorly in the postoperative period[36].

Dorsal augmentation

A low dorsum may be the result of deficiency in the upper third, middle vault (saddle nose deformity), or nasal tip. This is commonly seen in Asian and African American populations. It can also be the result of prior trauma or rhinoplasty. Dorsal augmentation can be used to address this concern. Alloplastic materials are commonly used for this grafting technique in Asia, while autografts tend to be more widely used in the West[4]. With autologous grafts, septal, conchal, or costal cartilage can be used for a dorsal onlay graft to augment the dorsum[37]. Costal cartilage is particularly beneficial for patients requiring larger reconstructions. In order to camouflage larger underlying grafts and mask minor surface irregularities, especially in patients with thin skin, dermal fat grafts and posterior auricular fascia grafts may be used[38,39].

Diced cartilage can also be used for dorsal augmentation, either on its own to fill in dorsal irregularities, or wrapped in a sheet in order to minimize risk of dispersion[40]. This concept was initially introduced by Erol in 2000 as the “Turkish delight,” a technique whereby authors wrapped diced cartilage in Surgicel to form a cylindrical graft. Erol’s original study of 2,365 patients demonstrated a graft reabsorption rate of 0.5% with this technique[41]. However, given concerns regarding unacceptably high resorption rates in other studies, there have been several modifications of this concept, including diced cartilage wrapped in temporal fascia. The source of cartilage does not affect the graft in this case, as the material is minced into tiny pieces (approximately 0.5 to 1.0 mm in size), ultimately negating differences in intrinsic properties between elastic-type and hyaline-type cartilage. The advantage of diced cartilage is the ability to mold and reshape the graft for up to 3 weeks postoperatively. It is also advantageous in its ability to blend and mask dorsal irregularities[14].

Different individuals have also had success combining morselized cartilage graft with fibrin glue[42,43]. Fibrin glue has been shown to improve skin graft take and promote wound healing[44]. It also promotes cartilage growth by providing a scaffold for stabilization and diffusion of nutrients[45]. Cartilage is diced into 0.5 to

Spreader grafts

Spreader grafts are used in functional rhinoplasty to address static narrowing of the nasal valve. Septal cartilage is preferred for this graft. Conchal cartilage can be used, but its curvature makes sculpting more difficult. The rectangular graft is made to be the length of the upper lateral cartilage (ULC), approximately 25 mm in length and preferably 3-5 mm wide and 2 mm thick[47]. It can be placed via an open or endonasal approach. The ULC and septum are separated[48]. The graft is then placed in a pocket between the septum and the ULC [Figure 1]. The effect is widening of the angle of the internal nasal valve.

Figure 1. Illustration of the location of spreader graft placement (green) between the septum and the ULC. ULC: Upper lateral cartilage.

Flaring sutures can also be placed to further lateralize the ULCs[49]. This is a horizontal mattress stitch placed through the caudal and lateral border of the ULC, across the dorsum to the contralateral ULC. When this stitch is tightened, it increases the cross-sectional area of the internal nasal valve by even more than spreader grafts alone[50]. Cosmetically, this technique has the advantage of defining dorsal aesthetic lines, although it necessarily widens the dorsum.

Nasal Tip

Understanding the “nasal tripod” is key for the reconstruction of the nasal tip and mastery of tip dynamics. First coined by Anderson in 1969, this concept describes the structural support of the nasal tip as a tripod: the lateral crura form two legs, and the medial crura come together to form the third leg[51]. Columellar strut and SEGs are two workhorse grafts used to address nasal tip positioning. Both are used to strengthen the mesial limb of the tripod for continued postoperative tip support.

Columellar strut

The columellar strut graft (CSG) can help increase tip projection and address a ptotic tip. Septal cartilage is preferred given its strength; costal and conchal cartilage may also be considered. The graft should be straight and thick enough to provide adequate support. Gunther and Guyuron recommend using the base of septal cartilage where it connects to the vomer, as the cartilage is generally thickest in this region[47]. Mo and Jung describe a non-incisional, double-layered conchal cartilage graft for this technique that also achieves adequate tip projection and rotation[52]. Regardless of the cartilage source, the graft is ultimately placed between the medial crura, just above the nasal spine. Its superior extent should lie just below the level of the domes[53]. The graft itself measures approximately 14-16 mm long, 2-3 mm wide, and 1-2 mm thick. The graft is sutured to the medial crura in three places, equally spaced apart, along the length of the graft with 5-0 polydioxanone (PDS)[54].

Septal extension graft

SEGs also address tip projection and rotation. They usually measure approximately 18-20 mm long, 10 mm wide, and 1-2 mm thick[54]. The graft is usually placed through an open approach and is ideally made with septal cartilage. As with the CSG, conchal cartilage with its concave sides folded onto themselves may be used as a viable alternative, with no difference in projection or rotation compared to septal cartilage graft[55,56]. The graft itself is most often overlapped against one side of the caudal septum, held in position with needles, and sutured in place with mattress sutures along at least three points. This technique is particularly useful in patients with a deviated caudal septum, as the graft can be positioned on the side away from the deviation. However, if this end-to-side approach creates the appearance of septal deviation from midline, another option is the end-to-end technique. With this technique, the graft is placed end-to-end with the caudal septum and reinforced on either side with extended spreader grafts. After the graft is positioned against the septum, an interdomal suture is placed to help set tip rotation and projection. The graft is then secured to the medial crura with horizontal mattress stitches[57,58].

SEGs have been reported to yield better patient-reported cosmetic outcomes and appear to have a superior ability to maintain tip projection and rotation over time. Lathif et al. studied air flow dynamics and patient perceived cosmetic outcomes in SEGs compared with CSGs. They found greater patient perceived cosmetic results in SEGs, but similar functional outcomes between the two groups. Over an eight-month period, they also found less distortion in the nasolabial angle for SEGs compared to CSGs[54]. Bellamy and Rohrich conducted a retrospective review comparing long-term postoperative changes in tip projection and rotation in patients who received a CSG compared to a SEG. They found the incidence of clinically significant projection loss at one year postoperatively was 55% in CSG patients, compared to 8% in SEG patients. With regards to tip rotation loss at one year postoperatively, they found patients who received CSGs lost approximately 4.9 degrees of the nasolabial angle compared to a loss of 1.9 degrees for SEGs. They concluded tip projection and rotation are better maintained in SEGs compared to CSGs over time[59]. Kucukguven et al. came to a similar conclusion in a recent prospective study comparing long-term tip stability between these two grafts[57]. Mookerjee et al. found stable tip projection and rotation for caudal SEGs even several years postoperatively. The greatest loss of projection and rotation tends to happen within the first month after surgery for both techniques[57,60].

Cap graft

The cap graft is a tip graft usually made of minced septal cartilage. Minced cartilage can also be substituted with temporoparietal fascia. The cartilage is placed over the tip graft and secured with sutures. The effect is to camouflage any underlying graft, which is particularly helpful in patients with thin skin[53]. Conchal cartilage can also be used in this region, as its smooth contour blends in seamlessly at the nasal tip.

Shield graft

The shield graft is a trapezoid-shaped graft used to enhance tip definition. It is sutured onto the medial crural strut, from the medial crural footplate to the nasal tip, to bolster tip support [Figure 2]. Autologous cartilage is normally used, with the anterior end of the graft carved to be approximately 8-12 mm wide, with gradual tapering down to a posterior end measuring approximately 3-4 mm wide. It can extend several millimeters (usually 1-2 mm) above the nasal dome to achieve tip definition, and is particularly useful in patients with thick skin or an amorphous tip[53,58]. An open approach is favored for precise fixation of the graft itself. A common complication with this graft is visibility of graft edges especially in thin-skinned individuals. This risk may be minimized by carefully beveling the graft edges.

Plumping graft

Plumping grafts are diced cartilage placed in a pocket at the posterior columella. It can add volume to a retracted columella. It also increases the nasolabial angle, giving the appearance of increased tip rotation[53].

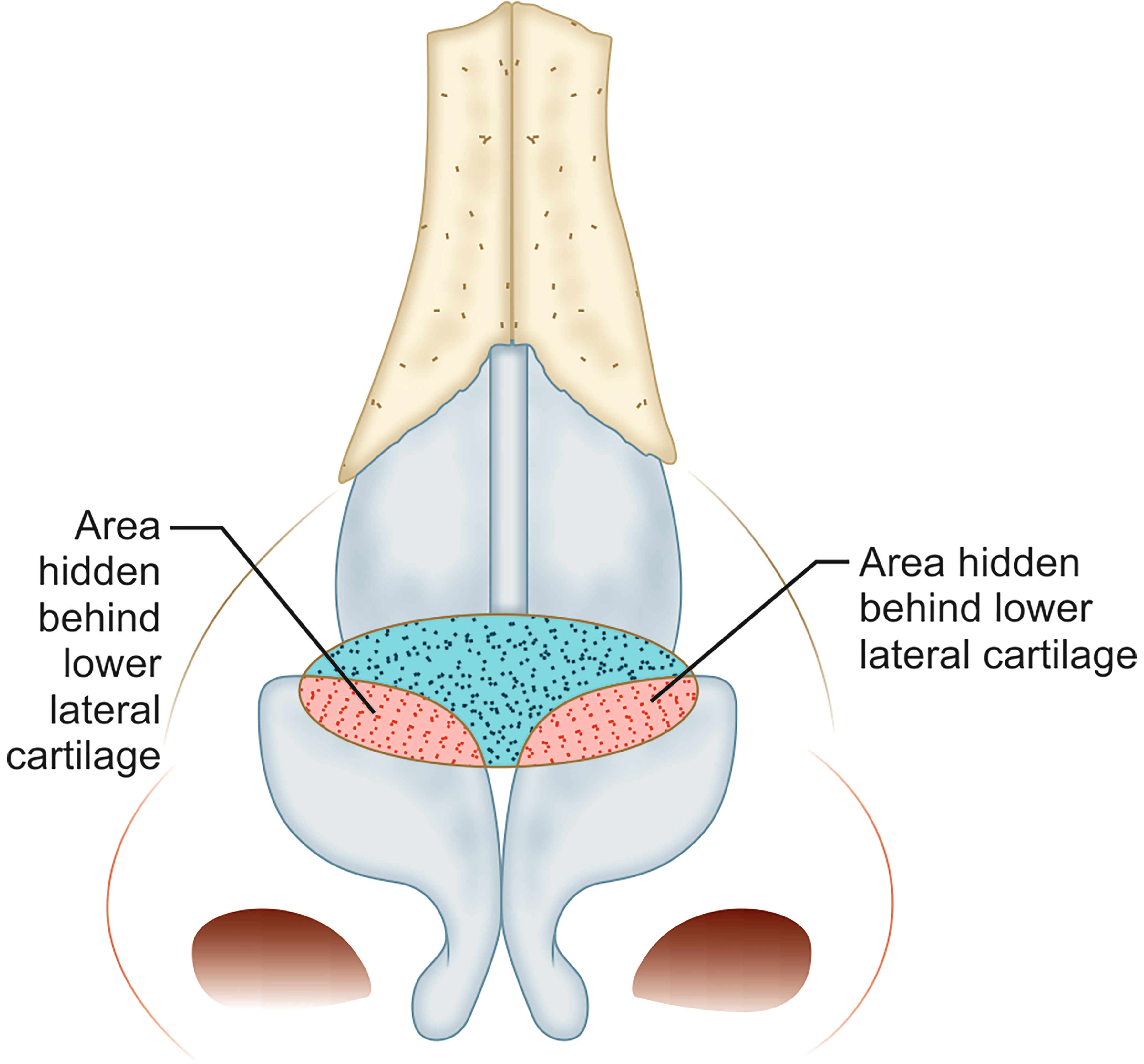

Upper lateral cartilage (ULC)/Lower lateral cartilage (LLC)

Graft techniques in this region are generally performed in functional septorhinoplasties in order to address nasal valve collapse and/or lateral wall insufficiency. There can be static collapse and/or dynamic collapse at the nasal valves. The external nasal valve is formed by the caudal septum and medial crura of the lower lateral cartilage (LLC) medially, the nasal floor inferiorly, and alar cartilage laterally. The internal nasal valve is formed by the caudal septum, ULC, and head of the inferior turbinate, and is approximately a 10-15-degree angle. It is the narrowest cross-sectional area of the nose and thus is the location of greatest resistance to airway flow[61]. This area is susceptible to dynamic collapse secondary to the Bernoulli effect: as air flow across a narrowed area increases in velocity, pressure decreases, resulting in the collapse of the lateral nasal wall[62].

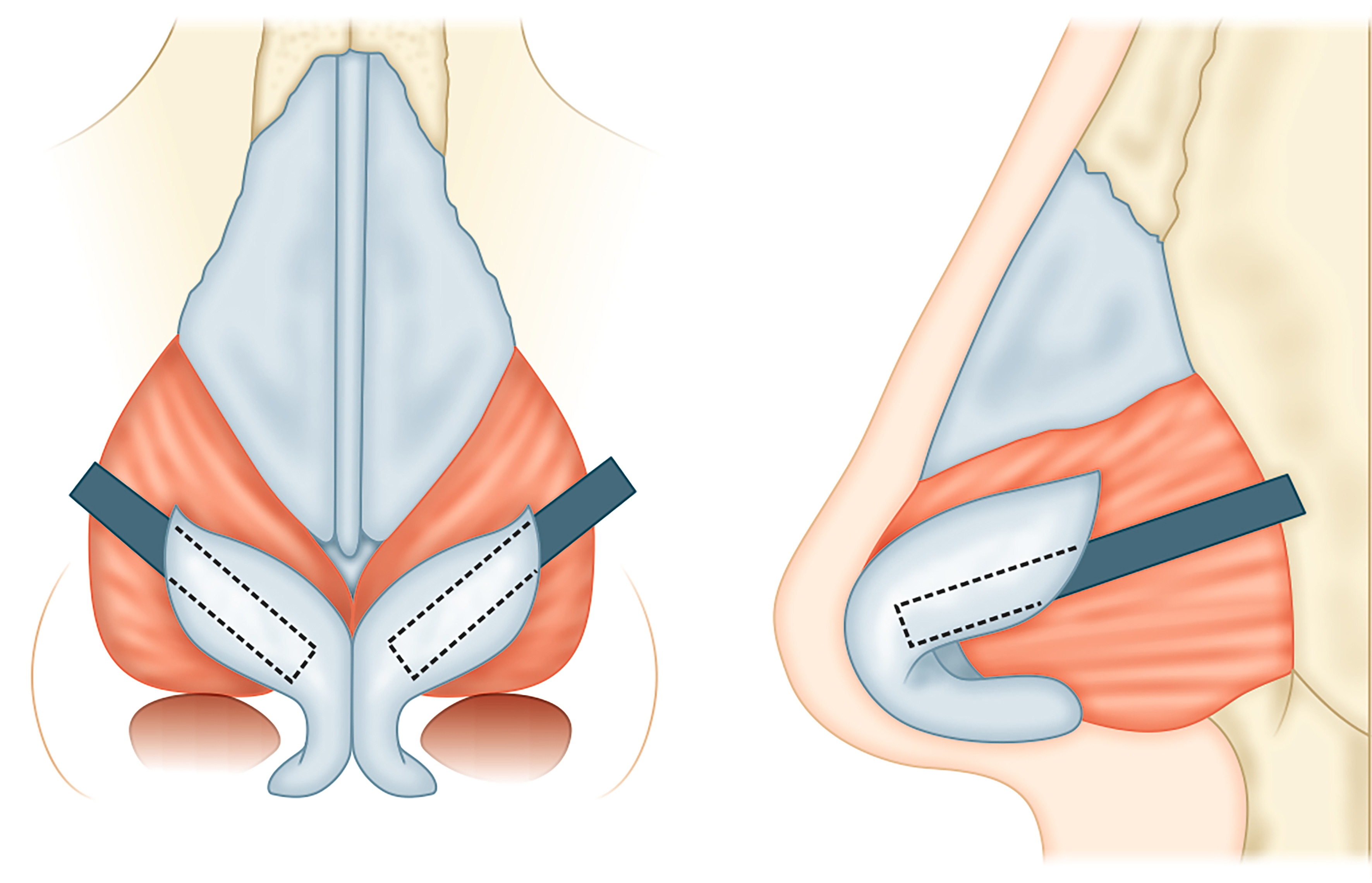

Lateral wall batten

The lateral wall batten is one of the most common grafting techniques in functional rhinoplasty. It is used to address dynamic internal and external nasal valve collapse and can be placed with either an endonasal or open approach. A septal or conchal cartilage graft is positioned at the center of collapse during inspiration, usually at the intervalve area of the nose. The graft is placed in a submucosal pocket superficial to the alar cartilage and secured with a through-and-through suture to collapse any existing dead space. It is important that the graft rests laterally at the bony piriform aperture. The graft should be slightly convex to help pull the side wall laterally [Figures 3 and 4]. Cosmetically, this grafting technique will widen the lateral nasal wall.

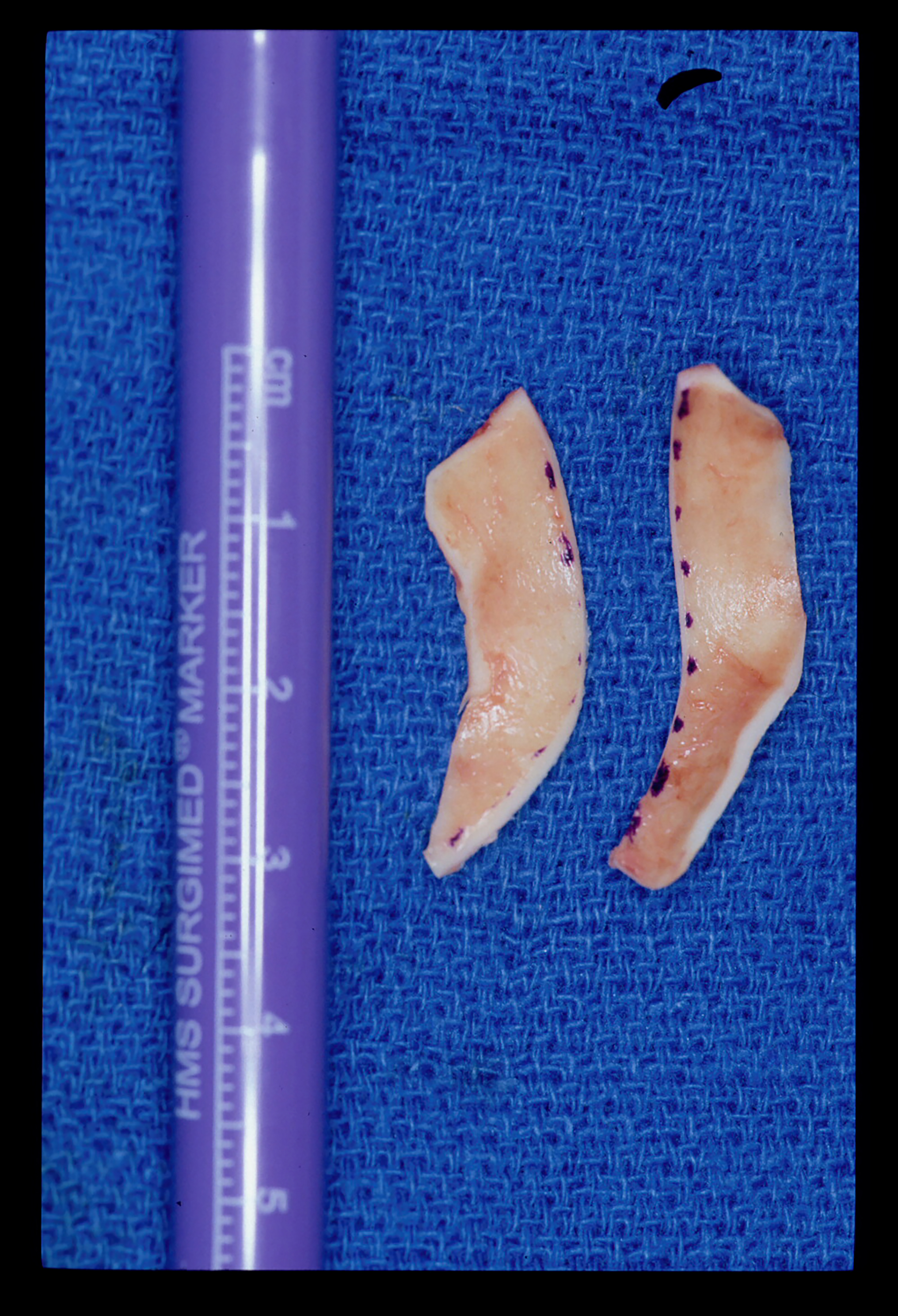

Lateral crural strut

Lateral crural strut grafts are secured to the deep surface of the lateral crura to help reinforce a weak, collapsible, malpositioned, or malformed lateral crus. They may also help correct alar rim retraction or address a boxy nasal tip[63]. Septal cartilage is favored, although conchal or costal cartilage may also be used. This graft should also extend onto the piriform aperture[2] [Figure 5].

Alar rim graft

The alar rim graft is placed in the soft tissue caudal to the border of the LLC. It is used for external nasal valve collapse as well as to correct alar rim retraction. The graft generally measures approximately 17-

Butterfly graft

The butterfly graft is a popular graft used to support the ULC in order to minimize dynamic collapse with inspiration[62]. It is an onlay graft that spans across the septum and overlies the ULC on either side [Figure 6]. It can be placed via an open or endonasal approach. Conchal cartilage is harvested, ensuring preservation of the anterior perichondrium, and carved to a final size of approximately 2 cm × 1 cm[64]. The edges are beveled to minimize their prominence externally. The caudal edge of the graft sits at the level of the scroll region. An inter-cartilaginous incision is made on either side and the superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) is released to the level of the rhinion, followed by subperiosteal dissection to the level of the nasion[62,64]. A depression is surgically created at the anterior septal angle in order to accommodate the planned overlying graft. Once the graft is placed, 5-0 PDS is used to secure the ULC to the medial caudal, then lateral margin of the graft on either side[62].

The butterfly graft has been shown to be superior in decreasing nasal airway resistance compared to spreader grafts. In a cadaver study, Brandon et al. noted a decrease in nasal resistance with the butterfly graft, spreader graft, and a bioabsorbable implant; however, the greatest decrease in airflow resistance was seen in cadavers that received a butterfly graft (24.9% decrease compared to 6.7% decrease for bioabsorbable implants and 2.6% decrease for spreader grafts)[48]. While this graft is functionally effective, one of the proposed drawbacks is visibility of the graft after placement and supratip fullness. This can be addressed with thinning of the cartilage graft. In a cadaveric study, Brownlee et al. found that grafts can be thinned approximately 50% while still maintaining the strength to prevent nasal valve collapse[65]. Despite concerns regarding aesthetics, Mims et al. found that casual observers did not identify the supratip region to be the least attractive area of the nose in butterfly graft or spreader graft patients. Respondents also did not find patients who underwent butterfly grafting to be less attractive postoperatively compared to preoperative photographs[66].

Septum

Septal batten graft

Septal batten grafts can be used to straighten a deviated caudal septum. While techniques - including scoring incisions, the cutting and suture technique, and the swinging-door method (which requires separation of the caudal septum from the anterior nasal spine) - have been used to address caudal septal deviation[67,68], these approaches may weaken cartilage and ultimately compromise tip support[69].

Bony batten grafts have been described to correct caudal septal deviation while minimizing the aforementioned complications. In this technique, a hemitransfixion incision is made and bilateral mucoperichondrial flaps are elevated. A bony graft is taken from the perpendicular lamina of the ethmoid or the vomer. The caudal septum can be divided at its most concave part, and the bony graft is placed along the concave side of the caudal septum. The graft is sutured to the cartilage along the length of the graft using 5-0 PDS. After the incision is closed, the septal mucosa is secured onto the grafted caudal septum with through-and-through mattress sutures. Nasal splints are placed to prevent the formation of septal hematoma. In 2020, Akashal conducted a case series that included 27 patients with caudal septal deviation who underwent septal bony batten grafts. He found 85% of these patients had a confirmed straightened septum on endoscopy postoperatively. There was also significant symptomatic improvement, as demonstrated by significant decrease in postoperative compared to preoperative Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scores[70]. Similar results were seen in a case-controlled retrospective study released the same year[71].

USE OF 3D IMAGING AND PRINTING

While 3D imaging and printing have existed for decades, their use in reconstructive rhinoplasty is a more recent development. Two-dimensional (2D) photography for preoperative planning, intraoperative guidance, and postoperative monitoring has been the standard for years. However, there are limitations to the standard 2D views of the nose (frontal, lateral, oblique, and base), as the nose itself is a 3D structure. 3D imaging technology and simulation software can be advantageous in surgical planning and intraoperative adjustments.

Another advantage of 3D imaging is the ability to better counsel patients regarding expected surgical outcomes and to discern patient preferences, goals, and motivations preoperatively[72]. 3D imaging has been noted by many to be an effective tool in building the surgeon-patient relationship. Lekakis et al. found that patients considered 3D simulation to provide added benefit over 2D simulation during rhinoplasty consults. Patients undergoing revision rhinoplasty have reported that 3D simulation helped them understand the goals of surgery. Additionally, 3D simulation appeared to provide additional reassurance to patients in this study[73].

3D printing can also be used in reconstructive rhinoplasty to optimize grafting outcomes. Three-dimensional-printed models can be made from simulated images created during a patient’s initial rhinoplasty consult and serve as surgical guides intraoperatively. Positioning guides have been described that begin at the forehead and extend down along the nasal profile to midline Cupid’s bow. These guides can be used throughout the case and will ultimately align with the nose once the desired outcomes are achieved[72]. In 2019, Choi et al. studied the surgical outcomes associated with 3D-printed rhinoplasty guides. The study examined surgical outcomes in patients whose surgeries utilized 3D-printed rhinoplasty guides compared to a control group. Choi et al. found a higher correlation between the simulated and postoperative measurements in the 3D-printed guide group compared to the control group; this was true for nasal tip projection, nasal dorsum height, and nasolabial angle measurements at 6 weeks postoperatively[74]. Despite the study’s small sample size and relatively short follow-up period of one year, it provides convincing evidence that 3D-printed guides may help surgeons more successfully achieve their planned rhinoplasty results.

CONCLUSION

This article provides a comprehensive, updated overview of grafting principles and techniques in reconstructive rhinoplasty. While autologous cartilage is considered the gold standard for grafting material in rhinoplasty, alloplastic grafts and homologous costal cartilage are suitable options, especially in cases of revision rhinoplasties or in certain patient populations with less abundant native nasal cartilage. Though incidence of infection, extrusion, warping, or resorption may potentially be higher with these alternative materials, surgeons must be able to: (1) understand the extent to which these adverse effects occur and (2) weigh the risk of these adverse effects against the benefits of more abundant grafting material, having a single surgical site, and decreased anesthesia time. Various grafts and recommended techniques are also described in detail. Continued advances in 3D imaging and printing technology are likely to produce superior surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction. Three-dimensional-printed intraoperative rhinoplasty guides specifically can help surgeons achieve their planned rhinoplasty outcomes by providing an opportunity for intraoperative adjustment and comparison.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Substantial contributions to conceptualization and writing, as well as to the design, acquisition, and analysis of data: Zhao A

Contributed to conceptualization, writing, and content review: Brownlee B

Principal investigator: contributed to conceptualization, writing, and content review: Park S

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Park S is a Guest Editor of the special issue “Updates and Advances in Reconstructive Rhinoplasty” in the journal Plastic and Aesthetic Research, also serves as an Editorial Board Member of the journal. Park S was not involved in any steps of the editorial process for this manuscript, including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Plastic Surgery Statistics Report. ASPS national clearinghouse of plastic surgery procedural statistics 2020. Available from: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2020/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2020.pdf. [Last accessed on 28 Oct 2025].

2. Mella J, Oyer S, Park S. Functional rhinoplasty-what really works? Laryngoscope. 2023;133:1002-4.

3. Ersek RA, Delerm AG. Processed irradiated bovine cartilage for nasal reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1988;20:540-6.

4. Park SS. Fundamental principles in aesthetic rhinoplasty. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;4:55-66.

5. Mella J, Christophel J, Park S. Are alloplastic implants safe in rhinoplasty? Laryngoscope. 2020;130:1854-6.

6. Chen K, Schultz BD, Mattos D, Reish RG. Optimizing the use of autografts, allografts, and alloplastic materials in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;150:675e-83.

7. Peled ZM, Warren AG, Johnston P, Yaremchuk MJ. The use of alloplastic materials in rhinoplasty surgery: a meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:85e-92.

8. Machado VF, Chagas RSD, Dos Reis PM, Grillo R. Extrusion of high-density porous polyethylene implants in the nose. J Craniofac Surg. 2025;36:e138-41.

9. Wright JM, Halsey JN, Rottgers SA. Dorsal augmentation: a review of current graft options. Eplasty. 16;23:e4.

10. Kim SG, Menapace DC, Mims MM, Shockley WW, Clark JM. Age-related histologic and biochemical changes in auricular and nasal cartilages. Laryngoscope. 2024;134:1220-6.

11. Dermody SM, Lindsay RW, Justicz N. Considerations for optimal grafting in rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2023;39:625-9.

12. Novak M, Cason R, Rohrich RJ. Role of rib graft for tip shaping in primary rhinoplasty: a retrospective case series of 30 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024;154:677e-81.

13. Wee JH, Park MH, Oh S, Jin HR. Complications associated with autologous rib cartilage use in rhinoplasty: a meta-analysis. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015;17:49-55.

15. Karasik D, Goslawski AM, Tranchito E, et al. Trends in rhinoplasty: insights from an international survey of facial plastic surgeons. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2025;53:686-91.

16. Hawellek T, Beil FT, Hischke S, et al. Costal cartilage calcification: prevalence, amount, and structural pattern in the general population and its association with age: a cadaveric study. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2024;26:481-7.

17. Faderani R, Arumugam V, Tarassoli S, Jovic TH, Whitaker IS. Preoperative imaging of costal cartilage to aid reconstructive head and neck surgery: a systematic review. Ann Plast Surg. 2022;89:e69-80.

18. Park AC, Hutchison DM, Prasad KR, et al. Costal cartilage considerations: novel use of handheld ultrasound device in rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2024;134:651-3.

19. Gibson T, Davis WB. The distortion of autogenous cartilage grafts: its cause and prevention. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 1957;10:257-74.

20. Lopez MA, Shah AR, Westine JG, O’Grady K, Toriumi DM. Analysis of the physical properties of costal cartilage in a porcine model. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007;9:35-9.

21. Taştan E, Yücel ÖT, Aydin E, Aydoğan F, Beriat K, Ulusoy MG. The oblique split method: a novel technique for carving costal cartilage grafts. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2013;15:198-203.

22. Wilson GC, Dias L, Faris C. A comparison of costal cartilage warping using oblique split vs concentric carving methods. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19:484-9.

23. Hanna SA, Mattos D, Datta S, Reish RG. Outcomes of the use of fresh-frozen costal cartilage in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024;154:324-8.

24. Welling DB, Maves MD, Schuller DE, Bardach J. Irradiated homologous cartilage grafts. Long-term results. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114:291-5.

25. Wee JH, Mun SJ, Na WS, et al. Autologous vs irradiated homologous costal cartilage as graft material in rhinoplasty. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19:183-8.

26. Vila PM, Jeanpierre LM, Rizzi CJ, Yaeger LH, Chi JJ. Comparison of autologous vs homologous costal cartilage grafts in dorsal augmentation rhinoplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146:347-54.

27. Luan CW, Chen MY, Yan AZ, et al. Complications associated with irradiated homologous costal cartilage use in rhinoplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2022;75:2359-67.

28. Jenny HE, Siegel N, Yang R, Redett RJ. Safety of irradiated homologous costal cartilage graft in cleft rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147:76e-81.

29. Toriumi DM. Choosing Autologous vs irradiated homograft rib costal cartilage for grafting in rhinoplasty. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19:188-9.

30. Suh MK, Lee SJ, Kim YJ. Use of irradiated homologous costal cartilage in rhinoplasty: complications in relation to graft location. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29:1220-3.

31. Kadhum M, Khan K, Al-Ghanim K, Castanov V, Symonette C, Javed MU. Fresh frozen cartilage in rhinoplasty surgery: a systematic review of outcomes. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2024;48:3269-75.

32. Wan R, Weissman JP, Williams T, et al. Prospective clinical trial evaluating the outcomes associated with the use of fresh frozen allograft cartilage in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11:e5315.

33. An Y, Shu F, Xie L, Zhen Y, Li X, Li Y. Use of nasal septal bone to straighten septal L-Strut in correction of east Asian short nose: a retrospective study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:1825-34.

34. Sun YD, Wu SQ, Wang Z, Zhao ZM, An Y. A safe technique for excising the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone in patients with crooked nose: a finite element analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2024;48:1084-93.

35. Byrd HS, Hobar PC. Rhinoplasty: a practical guide for surgical planning. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993:91;642-54.

36. Becker DG, Pastorek NJ. The radix graft in cosmetic rhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:115-9.

37. Pham TT, Winkler AA, Gadkaree SK. Functional and cosmetic considerations in saddle nose deformity repair. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2025;58:325-41.

38. Tan O, Algan S, Cinal H, Barin EZ, Kara M, Inaloz A. Management of saddle nose deformity using dermal fat and costal cartilage “sandwich” graft: a problem-oriented approach and anthropometric evaluation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74:1848.e1-14.

39. La Padula S, Pensato R, Pizza C, et al. The use of posterior auricular fascia graft (PAFG) for slight dorsal augmentation and irregular dorsum coverage in primary and revision rhinoplasty: a prospective study. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2024;48:862-71.

40. Dong W, Han R, Fan F. Diced cartilage techniques in rhinoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2022;46:1369-77.

41. Erol OO. The Turkish delight: a pliable graft for rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2229-41.

42. Bracaglia R, Tambasco D, D’Ettorre M, Gentileschi S. “Nougat graft”: diced cartilage graft plus human fibrin glue for contouring and shaping of the nasal dorsum. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:741e-3.

43. Stevenson S, Hodgkinson PD. Cartilage putty: a novel use of fibrin glue with morselised cartilage grafts for rhinoplasty surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:1502-7.

44. Currie LJ, Sharpe JR, Martin R. The use of fibrin glue in skin grafts and tissue-engineered skin replacements: a review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1713-26.

45. Bullocks JM, Echo A, Guerra G, Stal S, Yuksel E. A novel autologous scaffold for diced-cartilage grafts in dorsal augmentation rhinoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2011;35:569-79.

46. Tasman AJ. Dorsal augmentation-diced cartilage techniques: the diced cartilage glue graft. Facial Plast Surg. 2017;33:179-88.

47. Gunther S, Guyuron B. Economizing the septal cartilage for grafts during rhinoplasty, 40 years’ experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2021;45:224-8.

48. Brandon BM, Stepp WH, Basu S, et al. Nasal airflow changes with bioabsorbable implant, butterfly, and spreader grafts. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:E817-23.

49. Park SS. The flaring suture to augment the repair of the dysfunctional nasal valve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:1120-2.

50. Schlosser RJ, Park SS. Surgery for the dysfunctional nasal valve. Cadaveric analysis and clinical outcomes. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 1999;1:105-10.

51. Anderson JR. The dynamics of rhinoplasty. In: Proceedings of the Ninth International Congress in Otorhinolaryngology; 1969 Aug 10–14; Mexico City, Mexico. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica, International Congress Series No. 206; 1970.

52. Mo YW, Jung GY. A new technique in Asian nasal tip plasty: non-incisional double-layered conchal cartilage graft. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2021;74:1316-23.

53. Quatela VC, Kolstad CK. Creating elegance and refinement at the nasal tip. Facial Plast Surg. 2012;28:166-70.

54. Lathif A, Alvarado R, Kondo M, Mangussi-Gomes J, Marcells GN, Harvey RJ. Columellar strut grafts versus septal extension grafts during rhinoplasty for airway function, patient satisfaction and tip support. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2022;75:2352-8.

55. Namgoong S, Kim S, Kim HR, Jeong SH, Han SK, Dhong ES. Folded cymba concha: is it large and stable enough for caudal septal extension graft in Asian rhinoplasty? Aesthet Surg J. 2021;41:NP737-47.

56. Foda HMT, El Abany A. A novel ear cartilage caudal septal extension graft. Facial Plast Surg. 2023;39:408-16.

57. Kucukguven A, Çelik M, Altunal SK, Kocer U. Nasal tip flexibility and stability: comparison of septal extension grafts and columellar strut grafts in a prospective trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024;154:313-22.

58. Ansari K, Asaria J, Hilger P, Adamson PA. Grafts and implants in rhinoplasty-techniques and long-term results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;19:42-58.

59. Bellamy JL, Rohrich RJ. Superiority of the septal extension graft over the columellar strut graft in primary rhinoplasty: improved long-term tip stability. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;152:332-9.

60. Mookerjee VG, Shah J, Carney MJ, Alper DP, Steinbacher D. Long-term control of nasal tip position: quantitative assessment of caudal septal extension graft. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2024;48:187-93.

61. Wright L, Grunzweig KA, Totonchi A. Nasal obstruction and rhinoplasty: a focused literature review. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2020;44:1658-69.

62. Rist TM, Clark JM. Indications and evolution of the butterfly graft in nasal valve repair. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2025;58:279-93.

63. Gunter JP, Friedman RM. Lateral crural strut graft: technique and clinical applications in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:943-52.

65. Brownlee BP, Hassoun A, Parikh A, Chen XS, Zhao D, Mims MM. Cadaveric assessment of the butterfly graft in rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2024;134:1638-41.

66. Mims MM, Shockley WW, Clark JM. Casual observers’ perception on the aesthetics of the butterfly graft. Laryngoscope. 2023;133:2578-83.

67. İşlek A, Ciğer E. A proposal classification for caudal septal deviation with clinical implement. Eur J Plast Surg. 2022;45:569-73.

68. Voizard B, Theriault M, Lazizi S, Moubayed SP. North American survey and systematic review on caudal Septoplasty. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49:38.

69. Hosokawa Y, Miyawaki T, Akutsu T, et al. Effectiveness of modified cutting and suture technique for endonasal caudal septoplasty in correcting nasal obstruction and preventing nasal tip projection loss. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;50:35.

70. Aksakal C. Caudal septal division and batten graft application: a technique to correct caudal septal deviations. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;58:181-5.

71. Aksakal C. Surgical outcomes of bony batten grafting through endonasal septoplasty in the correction of caudal septum deviation. J Craniofac Surg. 2020;31:162-5.

72. Townsend A, Tepper OM. Virtual surgical planning and three-dimensional printing in rhinoplasty. Semin Plast Surg. 2022;36:158-63.

73. Lekakis G, Hens G, Claes P, Hellings PW. Three-dimensional morphing and its added value in the rhinoplasty consult. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7:e2063.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].