What “regenerative” means in aesthetic medicine: a narrative literature review attempting to demystify the core essence of regenerative aesthetics

Abstract

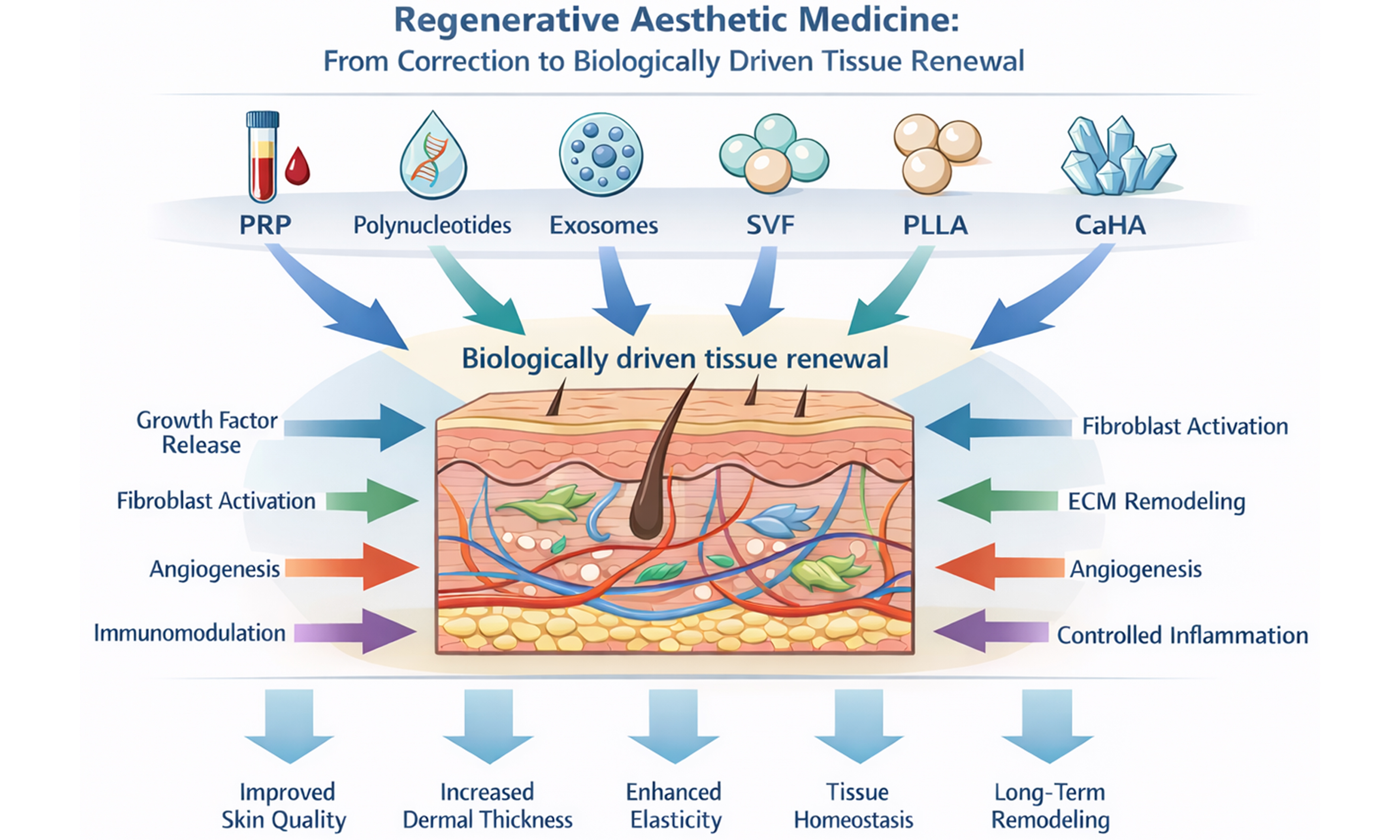

Regenerative aesthetic medicine has rapidly evolved from a primarily corrective discipline into a biologically oriented field focused on restoring tissue function, quality, and homeostasis. This narrative review examines the conceptual foundations of “regeneration” in aesthetic practice and critically discusses the biological rationale and clinical evidence supporting the main injectable modalities currently described as regenerative, including platelet-rich plasma (PRP), polynucleotides, exosomes, stromal vascular fraction (SVF)-based approaches, poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA), and calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA). These interventions act through distinct yet partially overlapping mechanisms, involving modulation of inflammation, fibroblast activation, extracellular matrix remodeling, angiogenesis, and immunobiological signaling. PRP provides concentrated growth factors with context-dependent effects on tissue repair; polynucleotides enhance fibroblast activity and dermal hydration through nucleotide-mediated pathways; exosomes function as intercellular signaling mediators influencing inflammatory cascades and tissue remodeling; SVF-based therapies combine volumetric support with paracrine and cellular effects; while PLLA and CaHA act as long-term biostimulatory fillers, promoting sustained neocollagenesis and dermal reorganization through controlled inflammatory and macrophage-mediated responses. Although clinical studies report improvements in skin quality parameters, dermal architecture, elasticity, and hair density, the available evidence is heterogeneous and often limited by variability in preparation methods, product characteristics, injection protocols, and outcome measures. Issues related to standardization, reproducibility, and regulatory classification remain particularly relevant for biologically derived products such as PRP, exosomes, and SVF. Overall, regenerative aesthetics represents a paradigm shift from transient correction toward biologically driven tissue renewal; however, consolidation within evidence-based aesthetic medicine will require higher-quality comparative trials, standardized methodologies, and clearer regulatory frameworks.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Over recent decades, aesthetic medicine has undergone substantial evolution, driven not only by advances in technologies and injectable products, but also by a progressively more integrated and personalized clinical approach aimed at improving tissue quality, function, and patient well-being. Within this context, the concept of “regeneration” has become increasingly central to minimally invasive aesthetic procedures, extending the therapeutic goal beyond immediate cosmetic correction toward longer-term biological tissue renewal. This shift represents a paradigmatic transition from a purely corrective model - traditionally focused on filling volume deficits or smoothing superficial wrinkles - toward a regenerative-oriented strategy that seeks to stimulate endogenous biological processes, including collagen and elastin synthesis, extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, angiogenesis, and cellular homeostasis[1]. As a result, aesthetic interventions are progressively evaluated not only for their visible outcomes, but also for their capacity to modulate tissue biology over time.

Regenerative medicine has been defined by Mason and Dunnill as “a multidisciplinary branch of medicine that replaces or regenerates human cells, tissues, or organs to restore or establish normal function”[2]. Rooted in advances in cell biology, tissue engineering, molecular biology, and biomaterials science, regenerative medicine emphasizes functional restoration rather than symptomatic or purely structural correction. Since its conceptual formalization in the late twentieth century, the field has increasingly aligned with translational and molecular medicine paradigms, fostering biologically driven therapeutic strategies across multiple clinical disciplines.

In aesthetic medicine, regenerative approaches have emerged as a rapidly expanding domain, encompassing biologically active substances and biomaterials intended to promote tissue rejuvenation and repair. According to the European Medicines Agency (EMA), regenerative therapies include products designed to repair, regenerate, or replace damaged tissues, encompassing cell-based therapies, gene therapies, and tissue-engineered products (EMA/CHMP/410869/2006). In everyday aesthetic practice, this conceptual framework has translated into the growing use of autologous and bioactive injectables - such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and polynucleotides - aimed at stimulating fibroblast activity, neocollagenesis, and dermal regeneration.

Despite its widespread adoption, the term “regenerative” is frequently used inconsistently within the aesthetic field, generating conceptual ambiguity and heterogeneous clinical interpretations. Among practitioners, definitions may vary according to scientific training, clinical background, or exposure to marketing-driven narratives. For patients, “regenerative” treatments are often perceived as inherently natural or minimally invasive, irrespective of the underlying biological mechanisms or strength of supporting evidence. This semantic dilution risks conflating rigorously studied regenerative or biostimulatory approaches with interventions whose effects are predominantly cosmetic or insufficiently validated. As regenerative aesthetics continues to expand, clearer definitions, evidence-based frameworks, and critical appraisal of emerging technologies are essential to ensure responsible clinical integration.

A broad range of injectable substances and techniques have been proposed as regenerative tools, supported by scientific evidence of varying robustness and quality. In this narrative review, we examine the biological rationale, mechanisms of action, clinical applicability, and limitations of the principal injectable modalities currently described as regenerative in aesthetic medicine, including:

· PRP: autologous blood-derived products enriched in growth factors.

· Polynucleotides: DNA-derived molecules, primarily obtained from fish or other biological sources.

· Exosomes: extracellular vesicles containing proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids involved in intercellular signaling.

· Stromal vascular fraction (SVF): adipose tissue-derived cellular and stromal components with paracrine and volumetric effects.

· Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA): an injectable polymeric biomaterial described as an aesthetic regenerative scaffold, capable of inducing controlled inflammatory responses and sustained collagen synthesis[3].

· Calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA): a hybrid filler combining immediate structural support with long-term biostimulatory effects.

The aim of this narrative review is to critically analyze the concept of “regeneration” as applied to aesthetic medicine by integrating mechanistic insights with available clinical evidence, while explicitly addressing heterogeneity, limitations, and unresolved controversies. Particular attention is given to differences in biological mechanisms, durability of effects, reproducibility, and regulatory considerations across modalities. Finally, we discuss how regenerative injectables may be incorporated into personalized, physiology-guided aesthetic strategies, highlighting the need for standardized methodologies and high-quality clinical studies to support safe, effective, and evidence-based practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This article is a narrative review aimed at providing a biologically grounded and clinically oriented overview of injectable modalities currently described as regenerative in aesthetic medicine.

A purposive literature search was conducted primarily using the PubMed database, employing English-language keywords related to regenerative aesthetics, including PRP, polynucleotides, Polynucleotides Highly Purified TechnologyTM (PN-HPTTM), exosomes, SVF, adipose tissue grafting, PLLA, CaHA, aesthetic regenerative medicine, and tissue regeneration in aesthetics. Publications in both English and Italian were considered. The time frame of interest spanned from 2012 to 2024.

The literature was selected with the objective of illustrating the biological rationale, mechanisms of action, and clinical applicability of the main regenerative and biostimulatory injectable approaches used in aesthetic practice. Priority was given to experimental studies, clinical investigations, and authoritative reviews that contributed to understanding tissue-level effects, safety profiles, and practical clinical considerations. When relevant to mechanistic interpretation, preclinical studies were also considered.

As a narrative review, the selection and interpretation of the literature were qualitative rather than systematic. The available evidence was examined critically, acknowledging heterogeneity in study design, outcome measures, treatment protocols, and levels of clinical validation across different modalities. No formal quality scoring or meta-analytic synthesis was performed.

For clarity and coherence, the discussion is organized into thematic sections corresponding to the principal injectable approaches addressed - PRP, polynucleotides, exosomes, SVF-based therapies, PLLA, and CaHA - with emphasis on mechanisms of action, clinical effects, durability, limitations, and areas of ongoing debate.

PLATELET-RICH PLASMA (PRP)

Introduction

PRP is an autologous blood-derived product characterized by an increased platelet concentration and widely investigated for its potential role in tissue repair and regenerative-oriented aesthetic medicine. Through centrifugation processes, platelets and their associated growth factors are concentrated, enabling modulation of cellular proliferation, angiogenesis, and ECM remodeling. In recent years, PRP has gained increasing attention for applications in skin rejuvenation, alopecia management, scar improvement, and dermal regeneration. This section provides an overview of PRP biochemical features, mechanisms of action, and main clinical applications[4,5]. Originally introduced in sports and orthopedic medicine for tendon and ligament repair, PRP was subsequently adopted in plastic surgery and dermatology, and more recently in aesthetic medicine. Owing to its autologous nature and biological activity, PRP is currently considered a biologically active adjunctive approach for improving skin quality and supporting tissue renewal processes, although clinical outcomes remain influenced by preparation methods and treatment protocols.

Mechanism of action

PRP typically contains a platelet concentration up to seven times higher than that of whole blood, depending on the preparation system used. Activated platelets release a variety of bioactive molecules, including:

· Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF), which promotes cellular proliferation and angiogenesis[6,7].

· Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), essential for neovascularization and tissue repair[8].

· Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF), supporting epidermal regeneration[9].

· Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β), involved in collagen synthesis and dermal remodeling[4].

· Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) and Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGFs), which enhance cellular growth and ECM production[10,11].

The wound healing cascade is referenced here as a biological model to contextualize the mechanisms through which PRP exerts its effects in aesthetic medicine. Although aesthetic indications do not involve overt tissue injury, PRP-mediated modulation of inflammation, angiogenesis, and ECM remodeling largely mirrors the early and intermediate phases of physiological wound repair, thereby providing a useful framework for understanding its regenerative-oriented activity.

Wound healing progresses through three overlapping phases. During the inflammatory phase (approximately 3 days), PRP contributes to cytokine release, macrophage activation, and debris clearance[5,7]. The proliferative phase (approximately 10 days) is characterized by fibroblast and keratinocyte activation, increased collagen production, and angiogenesis driven primarily by VEGF[4,8]. Finally, during the remodeling phase (up to one month), ECM maturation and dermal reorganization occur, potentially resulting in improved skin firmness and elasticity[10,11].

Applications in aesthetic medicine

PRP is widely used in aesthetic practice for skin rejuvenation, where clinical studies have reported improvements in skin texture, elasticity, tone homogeneity, and hydration. Histological and imaging-based analyses have demonstrated increased collagen deposition and dermal thickness following PRP treatment; however, the magnitude of these effects varies substantially across studies, reflecting heterogeneity in PRP preparation systems, platelet concentrations, injection techniques, and outcome measures[8-10].

Conclusions

PRP represents a versatile and biologically active modality within regenerative-oriented aesthetic medicine, with a favorable safety profile and broad clinical applicability. Despite encouraging clinical observations, important limitations persist, particularly related to the lack of standardized preparation methods, variability in platelet and leukocyte content, and heterogeneity of treatment protocols. These factors contribute to inconsistent clinical outcomes and limit the strength of comparative conclusions. Future research should focus on protocol standardization, objective outcome assessment, and well-designed randomized clinical trials to better define the role of PRP relative to other regenerative and biostimulatory injectable approaches.

POLYNUCLEOTIDES

Introduction

Polynucleotides are linear nucleotide chains, usually extracted from fish DNA. They represent one of the most recent advances in regenerative aesthetic medicine due to their ability to stimulate fibroblast activity, promote collagen synthesis, and enhance tissue hydration by binding large amounts of water[12]. These properties make them particularly effective in managing skin aging, dermal biostimulation, and the regeneration of damaged tissues. Initially used in ophthalmology for corneal ulcer treatment, they have since expanded into dermatological and aesthetic applications.

Polynucleotide-based products are often marketed as “biostimulants” or “biorevitalizers”, aiming to improve overall skin quality[13]. Clinical evidence supporting the use of polynucleotides in aesthetic medicine is steadily growing. Various studies report improvements in brightness and elasticity, particularly after a treatment cycle of four sessions spaced 2-3 weeks apart. Their application to the neck, décolleté, and hands has also yielded positive results in terms of skin laxity reduction and trophic enhancement[13-15].

Some authors propose combining polynucleotides with other agents, such as hyaluronic acid and vitamins, in integrated biorevitalization protocols to enhance hydration, stimulation, and shorten recovery times[16].

Mechanism of action

Polynucleotides act primarily through two mechanisms:

· A2A adenosine receptor activation, which triggers intracellular signaling cascades leading to VEGF and angiopoietin production. This promotes neovascularization, tissue repair, improved local circulation, and fibroblast metabolism[17].

· Nucleotide salvage pathway, which allows for the recovery and reuse of degraded nucleotides for the synthesis of new nucleic acids. This mechanism supports cell proliferation and tissue turnover, contributing to the repair of damaged skin cells[18].

In vitro studies show that fibroblast exposure to polynucleotides significantly increases metabolic activity and collagen/elastin production[13]. Their high hydrophilicity improves ECM hydration, fostering a regenerative microenvironment[17].

Applications in aesthetic medicine

Main applications include:

· Clinical studies have reported improvements in skin elasticity and wrinkle-related parameters following polynucleotide treatment.[19].

· Elasticity and hydration: in a study of 143 patients, skin elasticity increased by 21.78% and hydration by 14.69% following polynucleotide infiltrations, suggesting it as a valid alternative to hyaluronic acid for biostimulation[20].

· Reduction of erythema and facial redness: intradermal PN injections, particularly when combined with hyaluronic acid, effectively reduced inflammation and improved complexion in patients with diffuse erythema[21].

· Body skin biostimulation: recent studies confirm their effectiveness in treating areas such as the neck, arms, and thighs, improving tone and countering photoaging and laxity[14].

Side effects are generally mild and transient (pain, erythema, bruising, swelling). Given their fish DNA origin, allergic reactions are rare, particularly due to extensive purification processes[15]. However, the rejuvenating effects of polynucleotides tend to be more gradual and subtle compared to volumizing fillers, and maintenance treatments are often necessary.

Conclusions

Polynucleotides are a valuable addition to regenerative aesthetic medicine, providing anti-inflammatory, hydrating, and pro-collagen benefits with a strong safety profile. Through adenosine receptor activation and ECM renovation, they effectively combat signs of aging, support skin quality, and enhance wound healing. Their gradual and subtle results make them ideal for long-term skin health strategies. Continued research and clinical standardization will help optimize protocols and broaden applications.

EXOSOMES

Introduction

Exosomes are nanosized (30-200 nm) extracellular vesicles released by nearly all living cells. They contain a bioactive cargo of proteins, lipids, messenger RNA (mRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and DNA, and play a key role in intercellular communication. In recent years, their application in aesthetic medicine has attracted growing interest due to their regenerative, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory properties. This section summarizes current knowledge on exosomes in dermatology and aesthetic medicine, with particular emphasis on mechanisms of action and potential clinical applications[22-25]. Despite growing experimental and preclinical evidence supporting their biological activity, the clinical translation of exosome-based therapies in aesthetic medicine remains at an early stage. Current applications are characterized by heterogeneity in product sources, isolation methods, and regulatory classification, which complicates interpretation of clinical outcomes and comparison across studies.

It should be noted that a significant proportion of commercially available exosome-based products used in aesthetic practice are plant-derived and are currently not classified as medicinal products under EMA regulations. As such, their clinical use remains confined to cosmetic or investigational contexts, and standardized regulatory pathways for humanderived exosome therapies in Europe have yet to be established.

Mechanism of action

Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSC-exos) regulate inflammation and immune responses through immunosuppressive miRNAs such as miR-21 and miR-146a. These molecules inhibit M1 macrophage activation while promoting the M2 phenotype, which is associated with tissue repair and regeneration[24,25]. Exosomes also reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines - including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-1β - thereby attenuating chronic inflammation[26,27]. In addition, exosomes enhance cellular proliferation and ECM synthesis by increasing the production of collagen types I and III, elastin, and fibronectin. These effects contribute to improvements in dermal architecture and skin quality. A key pathway involved is TGF-β/Smad signaling, which regulates ECM metabolism and protects against collagen degradation[22-25]. However, the intensity and durability of these effects appear to depend on exosome origin, cargo composition, and concentration, which vary substantially between preparations. Exosomes also modulate pathways involved in tissue regeneration and hair growth. Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway promotes dermal papilla cell proliferation and supports the transition of hair follicles into the anagen phase[24,26], while modulation of the Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) pathway enhances cell survival and reduces apoptosis[25,27]. Nevertheless, most mechanistic insights derive from in vitro or animal models, and their direct translation to predictable clinical outcomes remains incompletely defined.

Applications in aesthetic medicine

In skin rejuvenation, exosomes have been reported to improve elasticity and firmness by stimulating collagen and elastin production[25,26]. They may also counteract oxidative stress via activation of the Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) pathway, protecting skin cells from ultraviolet (UV)-induced damage and reducing chronic inflammation - processes considered relevant for skin repair and aging modulation[25,26]. However, clinical studies remain limited in number, sample size, and methodological standardization. In scar management, mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes have shown the ability to accelerate healing by acting early in the inflammatory phase, promoting angiogenesis, and modulating ECM remodeling. Experimental and preliminary clinical data suggest potential efficacy in hypertrophic and keloid scars through inhibition of myofibroblast differentiation and excessive collagen deposition[22,27]. Nonetheless, robust comparative clinical trials are lacking. In hair restoration, exosomes stimulate dermal papilla cell activity and support follicular regeneration via Wnt/β-catenin signaling, potentially prolonging the anagen phase and delaying catagen[24,26]. While these findings support a biological rationale for use in androgenetic alopecia, current clinical evidence is heterogeneous, and standardized treatment protocols have yet to be established. Exosomes have also been explored in pigmentation disorders. By modulating tyrosinase activity and influencing melanosome transport, keratinocyte-derived exosomes have been investigated for the management of melasma and other dyschromias[25,27]. These applications remain investigational and require further validation.

Conclusions

Exosomes represent a highly promising but still experimental tool in regenerative-oriented aesthetic medicine, owing to their capacity to modulate inflammation, intercellular signaling, and tissue remodeling[22-25]. However, significant challenges remain regarding standardization of isolation and purification methods, reproducibility of exosome cargo, dosing strategies, and regulatory classification. At present, variability in source material and manufacturing processes limits the comparability of clinical results and constrains widespread clinical adoption. Future research should prioritize standardized production protocols, clearer regulatory frameworks, and well-designed clinical trials to define the safety, efficacy, and appropriate positioning of exosome-based therapies within evidence-based aesthetic medicine.

SVF (STROMAL VASCULAR FACTOR)

Introduction

The SVF represents an advanced application of autologous adipose tissue within regenerative-oriented aesthetic medicine. Compared with conventional lipofilling, SVF-based approaches involve the harvesting and injection of finely processed adipose tissue enriched with stromal and vascular cellular components, including adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), pericytes, endothelial progenitor cells, and bioactive growth factors. This technique has been applied for the correction of volume deficits and signs of facial aging, including challenging areas such as the periocular region[28]. Adipose tissue is increasingly recognized not merely as an energy reservoir, but as a metabolically active endocrine and paracrine organ. Its stromal component contributes to tissue regeneration through the secretion of angiogenic and trophic factors, modulation of inflammation, and support of ECM remodeling[29]. Historically, autologous fat grafting was first described by Neuber in 1893 for facial defect correction[30], and has since evolved into a widely used technique in aesthetic and reconstructive surgery. Over time, refinements in harvesting, processing, and injection techniques have expanded its potential applications toward regenerative medicine[31]. ADSCs have been proposed as a particularly attractive source of autologous mesenchymal stem cells due to their relative abundance and ease of extraction through minimally invasive liposuction procedures[32,33]. Their capacity for self-renewal and multilineage differentiation provides a biological rationale for their use in tissue augmentation and regenerative-oriented aesthetic treatments. Nevertheless, the extent to which these properties translate into consistent and durable clinical outcomes remains an area of ongoing investigation.

Mechanism of action

SVF exerts its effects through a combination of volumetric, regenerative, and biostimulatory mechanisms:

· Volumizing effect: the injection of autologous adipose tissue restores volume lost due to aging or weight loss, particularly in the midface and periorbital regions.

· Regenerative effect: the SVF contains ADSCs, pericytes, and endothelial progenitor cells that contribute to angiogenesis, tissue repair, and graft integration.

· Biostimulatory effect: paracrine interactions between ADSCs and dermal fibroblasts may stimulate collagen synthesis and improve skin quality over time[29].

SVF techniques typically involve harvesting adipose tissue using fine cannulas from donor sites such as the abdomen, hips, or thighs. The tissue is subsequently processed through filtration or gentle centrifugation to obtain micro-fragmented grafts, which are injected superficially using microcannulas. Experimental and clinical observations suggest that smaller fat clusters and more superficial placement may favor graft survival and regenerative signaling[34]. The SVF contains a heterogeneous and interconnected cellular population, including adipocyte progenitors, pericytes, and endothelial cells, whose collective secretory activity supports angiogenesis and revascularization of the grafted tissue[35].

These methodological advancements were anticipated by Nguyen et al.[36], who first demonstrated that micro-injection of finely processed autologous adipose tissue could function effectively as a dermal filler, combining volumetric correction with regenerative biological potential.

Despite these biological advantages, SVF outcomes remain highly dependent on harvesting technique, processing method, injection depth, and operator expertise. Variability in these parameters contributes to heterogeneous clinical results and limits reproducibility across different practitioners and studies.

Applications in aesthetic medicine

SVF-based and micro-SVF techniques have been proposed as methods to obtain regenerative tissue with minimal manipulation, combining volumetric correction with biologically mediated skin improvement. When injected into the subdermal plane, SVF may exert both structural and regenerative effects, potentially improving skin texture and quality while restoring volume. Although SVF is typically injected at the subcutaneous level, its biological effects extend beyond volumetric correction. Paracrine signaling from adiposederived stromal cells and associated growth factors promotes angiogenesis, fibroblast activation, and ECM remodeling in the overlying dermis, highlighting the functional crosstalk between hypodermal and dermal compartments. Compared with traditional lipofilling, SVF approaches aim to enhance graft integration and biological activity; however, clinical evidence supporting superior outcomes remains limited and heterogeneous. Reported benefits are often derived from small case series or non-comparative studies, and standardized outcome measures are lacking. In addition, the technique requires familiarity with adipose tissue handling, and clinical success is closely linked to operator training and procedural precision.

Conclusions

SVF represents a promising regenerative-oriented approach within aesthetic medicine, offering the combined advantages of autologous volumization and biologically active tissue signaling. Its autologous nature reduces the risk of immunological or allergic reactions, and reported complication rates are generally low when performed by experienced practitioners. Nevertheless, SVF remains a technique-dependent procedure, with outcomes strongly influenced by harvesting, processing, and injection variables. While regenerative effects are biologically plausible and clinically encouraging, complete graft integration cannot be guaranteed, and partial resorption may occur, sometimes necessitating additional treatment sessions. At present, variability in protocols and limited high-quality comparative studies constrain definitive conclusions regarding efficacy and long-term regenerative benefit. Further controlled clinical investigations and greater procedural standardization are required to define the optimal role of SVF relative to conventional lipofilling and other regenerative injectable therapies.

POLY-L-LACTIC ACID

Introduction

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) is a biocompatible, biodegradable, and bioresorbable polymer widely used in medical applications due to its favorable physicochemical properties[37,38]. Chemically, PLLA is a poly-α-hydroxy acid synthesized from lactic acid, which exists as two optically active stereoisomers: L-lactic acid and D-lactic acid. Polymerization of optically pure L-lactic acid produces the homopolymer PLLA[39].

Compared with PDLA, which derives from D-lactic acid polymerization, PLLA exhibits higher crystallinity, improved chemical stability, and greater resistance to degradation, resulting in a substantially longer resorption time. PLLA degradation produces L-lactic acid - an endogenous, non-toxic metabolite - whereas PDLA degradation yields D-lactic acid, which is less physiologically favorable. PDLA also induces higher-grade skin inflammation and less collagen regeneration relative to PLLA. Additionally, PLLA is synthesized through eco-sustainable processes that avoid petroleum sources or poorly purified catalysts[37,40].

PLLA is one of the earliest biopolymers recognized as suitable for regenerative purposes. Its properties have been optimized to create scaffolds for tissue engineering, including skin regeneration[37]. Today, PLLA constitutes the primary material of the Poly Lactic Acid family used in medical cosmetology[39].

Mechanism of action

Unlike traditional fillers, which primarily work through immediate volume augmentation, PLLA induces controlled collagen neogenesis by stimulating fibroblasts[39]. When injected with a carrier solution, PLLA produces an initial volumizing effect that dissipates as the carrier is absorbed. The remaining microparticles undergo gradual hydrolysis into L-lactic acid, which is then metabolized, leading to fibroblast stimulation, collagen synthesis, and increased dermal thickness[41].

The degradation dynamics of PLLA determine the rate of L-lactic acid release, which in turn influences fibroblast activity and the overall collagenesis process. Variability in the biological performance of different PLLA formulations results from their distinct physicochemical characteristics, emphasizing the importance of understanding their molecular features[42].

Recent studies indicate that L-lactic acid functions as a multifunctional signaling molecule capable of regulating immune responses, angiogenesis, and tissue regeneration. Lactate has gained significant attention for its ability to stimulate endogenous collagen and elastin production[43,44]. Additionally, its role in skin rejuvenation is supported by its promotion of tissue repair and enhancement of cellular survival pathways driven by mitochondrial biogenesis[45].

Role of PLLA on fibroblast activation

PLLA stimulates collagen expression and synthesis in dermal fibroblasts primarily through activation of the TGF-β/Smad pathway - one of the main regulators of ECM turnover, fibroblast proliferation, and connective tissue remodeling[43]. PLLA increases TGF-β and IL-10 levels, leading to elevated Phosphorylated SMAD2 (pSMAD2)/SMAD2 and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) expression in senescent fibroblasts and aged skin. Additionally, PLLA induces α-SMA and PI3K p85α/AKT activation, promoting fibroblast proliferation and differentiation into myofibroblasts[41].

PLLA also inhibits matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 and significantly elevates tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases-1 and -2 (TIMP-1 and TIMP-2) levels, reducing ECM degradation. Overexpression of MMPs disrupts collagen and elastin synthesis, accelerates ECM breakdown, and contributes to wrinkle formation and skin laxity. By increasing collagen production and reducing ECM degradation, PLLA counteracts these aging-related processes[39,43].

Role of PLLA on macrophage polarization

Macrophages play an essential role in tissue regeneration by secreting cytokines and growth factors that promote fibroblast proliferation and migration[44]. For PLLA to exert regenerative activity without inducing chronic inflammation, microparticles must have a smooth, round morphology and a size between 20-50 µm[42,46-49]. Particle surface properties critically influence immune recognition: rough or spiculated surfaces promote IL-1 release and inflammasome activation, whereas smooth surfaces minimize inflammatory responses[41,46].

Two macrophage phenotypes are involved:

· M1 (pro-inflammatory): do not promote fibroblast proliferation.

· M2 (anti-inflammatory/regenerative): stimulate fibroblast activity and synthesis of collagen types I and III, and support proper tissue remodeling[41].

An increased ratio of M1 macrophages is associated with skin aging and chronic inflammation. PLLA counteracts this by increasing IL-4 and IL-13 levels, promoting polarization toward the regenerative M2 phenotype[41].

Role of PLLA on epidermal cells

PLLA microspheres have demonstrated beneficial effects on epidermal cell biology, particularly regarding cellular senescence. In vitro studies show that PLLA enhances proliferation and migration of primary epidermal stem cells (EpiSCs), while delaying senescence and differentiation, thereby preserving stemness. Consistent results have been observed in vivo following mesodermal PLLA injection. These findings provide new mechanistic insights into the anti-aging properties of PLLA[48].

Role of PLLA on adipocytes

Although less extensively investigated, adipocytes also appear to play a role in PLLA-based regenerative processes. A recent in vitro study showed that PLLA enhances adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis, while increasing expression of collagen types IV and VI at both transcript and protein levels. PLLA also mitigates UV-induced damage in adipocytes and supports recovery of adipogenesis and collagen expression within subcutaneous tissue[50,51].

Application in aesthetic medicine

Medical devices containing PLLA typically include PLLA microparticles combined with excipients such as sodium carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) and mannitol. Injectable formulations are generally provided as lyophilized powders[39,42]. Although these products share similar compositions, noteworthy differences often emerge in terms of injectability, degradation behavior, and complication profiles. Research indicates that efficacy and safety correlate with microparticle physicochemical features, particularly diameter and porosity, which influence degradation kinetics and regenerative activity[42].

A smoother, more regular microparticle morphology is associated with better safety outcomes, as irregular or rough particles may elicit foreign-body granulomas[42]. Clinically, PLLA treatments produce progressive improvements in skin quality and dermal thickness, requiring appropriate patient counseling regarding gradual onset. This slow, natural progression may also enhance patient satisfaction, as changes appear subtle and harmonious over time[51].

Facial indications

PLLA has been extensively used for facial rejuvenation worldwide and across multiple clinical studies. Indications include volume restoration, contour enhancement, wrinkle correction, and treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated lipoatrophy[38]. PLLA improves skin thickness and physiological parameters such as hydration, elasticity, transepidermal water loss, and overall skin quality - including erythema, pigmentation, pore size, luminosity, and smoothness. Its ability to improve cutaneous texture and firmness makes it a versatile option for facial aesthetic applications[39].

Body indications

PLLA is also widely applied in body rejuvenation. It effectively restores volume, improves laxity, and enhances contours and skin quality across various anatomical areas. Initially used off-face in the neck, chest, and hands - areas susceptible to photoaging - it has since been applied to the buttocks, arms, abdomen, knees, and thighs. Favorable results have also been reported in the treatment of scars and striae distensae[38].

Conclusions

PLLA is a promising regenerative biomaterial for tissue repair due to its tunable properties[37]. Its molecular and supramolecular characteristics are key determinants of biological response and clinical outcomes[42], particularly in regenerative aesthetics. PLLA microparticles provide a multi-level regenerative stimulus capable of supporting tissue renewal and physiological restoration of the skin.

CALCIUM HYDROXYAPATITE

Introduction

CaHA is one of the most extensively studied biostimulatory fillers in aesthetic medicine and serves as a paradigmatic model of the regenerative approach to cutaneous rejuvenation treatments. Composed of microspheres of calcium and phosphate ions, naturally occurring constituents of human bone and teeth, suspended in a CMC gel, CaHA exerts a dual effect: an immediate volumizing and mechanical action, followed by long-term biological stimulation of dermal regeneration[52].

Beyond functioning as a structural filler, CaHA actively interacts with the surrounding tissues, initiating a cascade of regenerative processes including neocollagenesis, neoelastogenesis, angiogenesis, and cellular proliferation. The systematic review by Amiri et al. (2023) synthesized data from 12 experimental and clinical studies, providing consistent evidence that CaHA stimulates fibroblast activity and upregulates the expression of genes responsible for type I and III collagen, elastic fibers, and neovascularization[52].

Within the broader framework of Regenerative Aesthetic Medicine, CaHA epitomizes the transition from a purely corrective approach to a biological and proactive paradigm, aiming to restore skin vitality and functionality through the activation of intrinsic tissue repair mechanisms.

Mechanism of action

The regenerative effects of CaHA arise from a biphasic mechanism, initially mechanical and subsequently biological, which leads to progressive dermal remodeling over time[52].

The two phases can be described as follows:

1. Immediate mechanical phase: immediately after injection, the CMC gel produces an instant lifting, support, and volumizing effect. As the carrier gel is gradually resorbed, the CaHA microspheres remain within the dermis, where they act as a three-dimensional scaffold, facilitating cell migration and ECM deposition[52].

2. Biological regenerative phase: over time, the persistence of CaHA microspheres induces a regenerative cellular response mediated by fibroblasts, macrophages, and endothelial cells, resulting in enhanced biosynthetic activity and progressive tissue remodeling.

The main biological processes involved include:

· Neocollagenesis: increased synthesis and deposition of type I and III collagen between 4 and 12 weeks post-treatment, leading to dermal thickening and improved elasticity[52].

· Neoelastogenesis: stimulation of elastin production and reorganization of elastic fibers, resulting in enhanced cutaneous firmness and resilience[53].

· Angiogenesis: formation of new capillary networks through the upregulation of VEGF and Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), improving tissue perfusion and metabolic efficiency[52].

· Cellular proliferation: stimulation of fibroblast and keratinocyte mitotic activity, increasing dermal density and hydration.

· Protective gene activation: recent in vitro studies have demonstrated that exposure of human fibroblasts to CaHA upregulates the expression of sirtuin 1 (SIRT-1) and SIRT-3, genes involved in cellular longevity and oxidative-stress response, suggesting a potential anti-senescence and cytoprotective effect of CaHA[54].

Clinical applications and regenerative use in aesthetic medicine

Skin quality improvement and bioremodelling

In its hyperdiluted form, CaHA acts primarily as a bioremodelling agent, promoting the synthesis of collagen and elastin without producing significant volumetric effect. Clinical studies using ultrasound evaluation have reported an increase in dermal thickness of up to 15% following two sessions of subdermal injections of diluted CaHA in the cervical region[54].

These findings support the role of CaHA in enhancing dermal architecture and elasticity through controlled stimulation of fibroblast activity and ECM renewal.

Facial rejuvenation and contouring

Due to its high viscosity and elasticity, CaHA is particularly suitable for structural support and contouring in facial areas such as the malar, mandibular, and chin regions.

Recent evidence has described its use in multilayer techniques, combining superficial and periosteal injections, demonstrating efficacy in improving facial shape, definition, and contour[55]. This rheological versatility allows CaHA to simultaneously restore volume and stimulate dermal regeneration, thereby addressing both structural and qualitative aspects of facial aging.

Emerging indications

A CaHA filler formulated in a CMC (CaHA/CMC) gel has demonstrated strong biostimulatory and skin-tightening properties, applicable not only to the face but also to multiple body regions for cutaneous rejuvenation[56].

Currently, the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indication for CaHA is hand rejuvenation; however, the European Medical Device Regulation (MDR) has recently authorized its use in the décolleté area. Despite the lack of large-scale randomized controlled trials, the application of diluted and hyperdiluted CaHA/CMC formulations to the neck, arms, thighs, abdomen, and other body regions has shown promising firming and regenerative effects. Although widely adopted in clinical practice and supported by a favorable safety profile, further controlled studies are required to validate these techniques scientifically[56].

CaHA in localized morphea

A recent multidisciplinary case report described the successful application of CaHA in a 24-year-old female patient affected by localized facial morphea[57]. The therapeutic protocol integrated plastic surgery, dermatology, and regenerative aesthetic medicine. Initially, autologous lipofilling was performed to restore lost volume, followed by the injection of CaHA-CMC in the affected area, after a multidisciplinary evaluation.

CaHA was selected for its biostimulatory potential, capable of activating fibroblasts, promoting neocollagenesis, and inducing gradual remodeling of the ECM, even in tissues with pre-existing fibrosis. During the 12-month follow-up, the patient exhibited a marked clinical and morphological improvement of facial contour and skin quality, characterized by progressive softening of the fibrotic tissue, restoration of skin elasticity, and absence of inflammatory reactivation or local complications[58].

This case illustrates the regenerative potential of CaHA even in autoimmune-related cutaneous conditions, demonstrating how synergy between plastic surgery, dermatology, and regenerative aesthetic medicine can represent an innovative therapeutic strategy for fibrotic dermal remodeling.

Conclusions

CaHA represents a cornerstone of Regenerative Aesthetic Medicine due to its dual mechanism of action, an immediate volumizing effect followed by long-term biostimulation that activates fibroblasts, promotes neocollagenesis, neoelastogenesis, and angiogenesis. Through modulation of fibroblast activity and remodeling of the ECM, CaHA supports structural and durable dermal rejuvenation, improving tone, density, and skin vitality. Furthermore, CaHA demonstrates a favorable safety profile, with adverse events that are generally mild and transient, such as erythema, swelling, and bruising[52].

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Regenerative aesthetic medicine represents an evolving area within aesthetic and dermatologic practice, characterized by a growing focus on biologically driven interventions aimed at improving tissue quality, function, and homeostasis. The present narrative review has examined the principal injectable modalities currently described as regenerative - including PRP, polynucleotides, exosomes, SVF-based approaches, PLLA, and CaHA - highlighting both their biological rationale and the heterogeneity of the supporting clinical evidence.

Overall, the available data indicate that these modalities exert their effects through distinct yet partially overlapping mechanisms, such as modulation of inflammation and oxidative stress, stimulation of fibroblast activity and ECM remodeling, promotion of angiogenesis, and regulation of intercellular signaling pathways. However, the strength and durability of these effects vary considerably across technologies and are strongly influenced by factors including product characteristics, preparation methods, injection techniques, and treatment protocols. As a result, direct comparison between modalities remains challenging, and claims of “regeneration” should be interpreted cautiously and within the context of current evidence.

An important finding emerging from this review is the contrast between scaffold-based biostimulatory fillers, such as PLLA and CaHA, for which longer-term clinical data and clearer mechanisms of sustained neocollagenesis are available, and biologically derived products such as PRP, exosomes, and SVF, which show promising biological activity but are characterized by greater variability, limited standardization, and heterogeneous clinical outcomes. For the latter group, issues related to reproducibility, regulatory classification, and quality of evidence remain particularly relevant and currently limit widespread, evidence-based adoption.

The clinical success of regenerative-oriented aesthetic treatments depends not only on the selected modality, but also on practitioner expertise, anatomical knowledge, and understanding of tissue physiology. Appropriate patient selection, accurate injection depth, dilution strategies, and technique-specific considerations play a crucial role in optimizing outcomes while minimizing complications. This is especially true for operator-dependent procedures, such as SVF-based approaches, where technical variability can significantly influence clinical results.

In conclusion, regenerative aesthetic medicine should not be viewed as a uniform or fully consolidated discipline, but rather as a dynamic and heterogeneous field in active development. While these injectable therapies offer the potential to shift aesthetic practice beyond transient correction toward biologically informed tissue modulation, their integration into routine clinical practice must be guided by realistic expectations, standardized protocols, and rigorous clinical research. Future progress will depend on high-quality comparative studies, improved methodological consistency, clearer regulatory frameworks, and ongoing practitioner education, ensuring that regenerative concepts are applied responsibly within an evidence-based aesthetic medicine paradigm.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

Graphical Abstract was created using Canva.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Cavallini M, Chittano Congedo E, Claysset B, Christopoulos G, Lim TS, Saucillo Gibert JR, Sundaram H, Arrigoni F, Merenda V

Methodology and literature analysis: Cavallini M, Chittano Congedo E, Claysset B, Christopoulos G, Lim TS, Saucillo Gibert JR, Sundaram H, Arrigoni F, Merenda V

Writing - original draft: Arrigoni F, Merenda V

Writing - review and editing: Cavallini M, Chittano Congedo E, Claysset B, Christopoulos G, Lim TS, Saucillo Gibert JR, Sundaram H, Arrigoni F, Merenda V

Supervision: Arrigoni F, Merenda V

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Zarbafian M, Fabi SG, Dayan S, Goldie K. The emerging field of regenerative aesthetics-where we are now. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:101-8.

3. Trovato F, Ceccarelli S, Michelini S, et al. Advancements in regenerative medicine for aesthetic dermatology: a comprehensive review and future trends. Cosmetics. 2024;11:49.

4. Samadi P, Sheykhhasan M, Khoshinani HM. The use of platelet-rich plasma in aesthetic and regenerative medicine: a comprehensive review. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43:803-14.

5. Leo MS, Kumar AS, Kirit R, Konathan R, Sivamani RK. Systematic review of the use of platelet-rich plasma in aesthetic dermatology. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:315-23.

6. Gupta S, Paliczak A, Delgado D. Evidence-based indications of platelet-rich plasma therapy. Expert Rev Hematol. 2021;14:97-108.

7. Justicz N, Derakhshan A, Chen JX, Lee LN. Platelet-rich plasma for hair restoration. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2020;28:181-7.

8. Everts P, Onishi K, Jayaram P, Lana JF, Mautner K. Platelet-rich plasma: new performance understandings and therapeutic considerations in 2020. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7794.

9. Asubiaro J, Avajah F. Platelet-rich plasma in aesthetic dermatology: current evidence and future directions. Cureus. 2024;16:e66734.

10. Lin MY, Lin CS, Hu S, Chung WH. Progress in the use of platelet-rich plasma in aesthetic and medical dermatology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:28-35.

11. Elghblawi E. Platelet-rich plasma, the ultimate secret for youthful skin elixir and hair growth triggering. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:423-30.

12. Maurizio C, Marco P. Long chain polynucleotides gel and skin biorevitalization. Available from: https://www.agfarma.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/2007-Cavallini-Papagni-JPD-Long-chain-polynucleotides-gel-ans-skin-biorivitalization-Plinest-143-pts.pdf. [Last accessed on 28 Jan 2026].

13. Bartoletti E, Cavallini M, Maioli L, et al. Introduction to polynucleotides highly purified technology. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365759324_Introduction_to_polynucleotides_highly_purified_technology. [Last accessed on 28 Jan 2026].

14. Bartoletti E, Trocchi G. Polynucleotides highly purified technology, the new class of body skin biorevitalizing agents. Available from: https://www.agfarma.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/2021-NR-4-BARTOLETTI-TROCCHI-AEM-narrative-PN-body-skin.pdf. [Last accessed on 28 Jan 2026].

15. Lee KWA, Chan KWL, Lee A, et al. Polynucleotides in Aesthetic Medicine: A Review of Current Practices and Perceived Effectiveness. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:8224.

16. Brandi C, Cuomo R, Nisi G, Grimaldi L, D’Aniello C. Face rejuvenation: a new combinated protocol for biorevitalization. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:400-5.

17. Cavallini M, Bartoletti E, Maioli L, et al. Consensus report on the use of PN-HPTTM (polynucleotides highly purified technology) in aesthetic medicine. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:922-8.

18. Maioli L. Polynucleotides highly purified technology and nucleotides for the acceleration and regulation of normal wound healing. Available from: https://www.agfarma.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/2020-NR-2-Maioli-L.-Polynucleotides-HPT-and-nucleotides-for-the-acceleration-and-regulation-of-normal-wound-healing.pdf. [Last accessed on 28 Jan 2026].

19. Lampridou S, Bassett S, Cavallini M, Christopoulos G. The effectiveness of polynucleotides in esthetic medicine: a systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2025;24:e16721.

20. Massirone A. Polynucleotides highly purified technology and the face skin, a history of innovative skin priming. Available from: https://www.ami.co.il/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/2021-NR-3-MASSIRONE-AEM-narrative-PN-face-skin.pdf. [Last accessed on 28 Jan 2026].

21. Lee DK, Oh M, Kim MJ, Oh SM. Clinical effects of polynucleotide with hyaluronic acid intradermal injections on facial erythema: effective redness treatment using polynucleotides. Skin Res Technol. 2024;30:e70034.

22. Vyas KS, Kaufman J, Munavalli GS, Robertson K, Behfar A, Wyles SP. Exosomes: the latest in regenerative aesthetics. Regen Med. 2023;18:181-94.

23. Zhang B, Gong J, He L, et al. Exosomes based advancements for application in medical aesthetics. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:1083640.

24. Olumesi KR, Goldberg DJ. A review of exosomes and their application in cutaneous medical aesthetics. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:2628-34.

25. Xiong M, Zhang Q, Hu W, et al. The novel mechanisms and applications of exosomes in dermatology and cutaneous medical aesthetics. Pharmacol Res. 2021;166:105490.

26. Ha DH, Kim HK, Lee J, et al. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cell-derived exosomes for immunomodulatory therapeutics and skin regeneration. Cells. 2020;9:1157.

28. Bernardini FP, Gennai A, Izzo L, et al. Superficial enhanced fluid fat injection (SEFFI) to correct volume defects and skin aging of the face and periocular region. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35:504-15.

29. Gennai A, Zambelli A, Repaci E, et al. Skin rejuvenation and volume enhancement with the micro superficial enhanced fluid fat injection (M-SEFFI) for skin aging of the periocular and perioral regions. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37:14-23.

30. Neuber F. Fettransplantation. Bericht uber die Verhandlungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie. (in German) Available from: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1581980076082320896. [Last accessed on 28 Jan 2026].

31. Pu LL, Yoshimura K, Coleman SR. Future perspectives of fat grafting. Clin Plast Surg. 2015;42:389-94.

32. Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4279-95.

33. Frese L, Dijkman PE, Hoerstrup SP. Adipose tissue-derived stem cells in regenerative medicine. Transfus Med Hemother. 2016;43:268-74.

34. Trivisonno A, Di Rocco G, Cannistra C, et al. Harvest of superficial layers of fat with a microcannula and isolation of adipose tissue-derived stromal and vascular cells. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34:601-13.

35. Wazer DE. 4-45 clinical treatment of radiotherapy tissue damage by lipoaspirate transplant: a healing process mediated by adipose-derived adult stem cells. Breast Dis Year Book Q. 2008;18:393-4.

36. Nguyen PS, Desouches C, Gay AM, Hautier A, Magalon G. Development of micro-injection as an innovative autologous fat graft technique: the use of adipose tissue as dermal filler. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1692-9.

37. Capuana E, Lopresti F, Ceraulo M, La Carrubba V. Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA)-based biomaterials for regenerative medicine: a review on processing and applications. Polymers. 2022;14:1153.

38. Christen MO. Collagen stimulators in body applications: a review focused on Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA). Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:997-1019.

39. Ao YJ, Yi Y, Wu GH. Application of PLLA (Poly-L-lactic acid) for rejuvenation and reproduction of facial cutaneous tissue in aesthetics: a review. Medicine. 2024;103:e37506.

40. Bravo BSF, Calvacante T, Nobre CS, Bravo LG, Zafra MC, Elias MC. Exploring the safety and satisfaction of patients injected with collagen biostimulators-a prospective investigation into injectable Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA). J Cosmet Dermatol. 2025;24:e16723.

41. Oh S, Lee JH, Kim HM, et al. Poly-L-lactic acid fillers improved dermal collagen synthesis by modulating M2 macrophage polarization in aged animal skin. Cells. 2023;12:1320.

42. Sedush NG, Kalinin KT, Azarkevich PN, Gorskaya AA. Physicochemical characteristics and hydrolytic degradation of polylactic acid dermal fillers: a comparative study. Cosmetics. 2023;10:110.

43. Zhu W, Dong C. Poly-L-lactic acid increases collagen gene expression and synthesis in cultured dermal fibroblast (Hs68) through the TGF-β/Smad pathway. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:1213-9.

44. Zou Y, Cao M, Tai M, et al. A feedback loop driven by H4K12 lactylation and HDAC3 in macrophages regulates lactate-induced collagen synthesis in fibroblasts via the TGF-β signaling. Adv Sci. 2025;12:e2411408.

45. Chirumbolo S, Bertossi D, Magistretti P. Insights on the role of L-lactate as a signaling molecule in skin aging. Biogerontology. 2023;24:709-26.

46. Baranov MV, Kumar M, Sacanna S, Thutupalli S, van den Bogaart G. Modulation of immune responses by particle size and shape. Front Immunol. 2020;11:607945.

47. Morhenn VB, Lemperle G, Gallo RL. Phagocytosis of different particulate dermal filler substances by human macrophages and skin cells. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:484-90.

48. Matlaga BF, Yasenchak LP, Salthouse TN. Tissue response to implanted polymers: the significance of sample shape. J Biomed Mater Res. 1976;10:391-7.

49. Dong Y, Zhang Y, Yu H, et al. Poly-L-lactic acid microspheres delay aging of epidermal stem cells in rat skin. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1394530.

50. Kim HW, Jung YA, Yun JM, et al. Effects of Poly-L-lactic acid on adipogenesis and collagen gene expression in cultured adipocytes irradiated with ultraviolet B rays. Ann Dermatol. 2023;35:424-31.

51. Avelar LE, Nabhani S, Wüst S. Unveiling the mechanism: injectable Poly-L-lactic acid’s evolving role-insights from recent studies. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2025;24:e16635.

52. Amiri M, Meçani R, Niehot CD, et al. Skin regeneration-related mechanisms of calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA): a systematic review. Front Med. 2023;10:1195934.

53. John S, Moorthy RK, Sebastian T, Rajshekhar V. Evaluation of hand function in healthy individuals and patients undergoing uninstrumented central corpectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy using nine-hole peg test. Neurol India. 2017;65:1025-30.

54. Dal Col V, Marchi C, Ribas F, et al. In vitro comparative study of calcium hydroxyapatite (Stiim): conventional saline dilution versus poly-micronutrient dilution. Cureus. 2025;17:e80344.

55. Trindade de Almeida AR, Marques ERMC, Contin LA, Trindade de Almeida C, Muniz M. efficacy and tolerability of hyperdiluted calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse) for neck rejuvenation: clinical and ultrasonographic assessment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023;16:1341-9.

56. Sato M, Muniz M, Ferreira LRC. Treatment of mid-face aging with calcium hydroxylapatite: focus on retaining ligament support. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2024;17:2545-53.

57. Schneider C, Parra Hernandez LA, Cure E, Salas I, Parra AM. Calcium hydroxyapatite as a co-adjuvant treatment option in a patient with morphea: a report of a case with a one-year follow-up. Cureus. 2024;16:e69741.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].